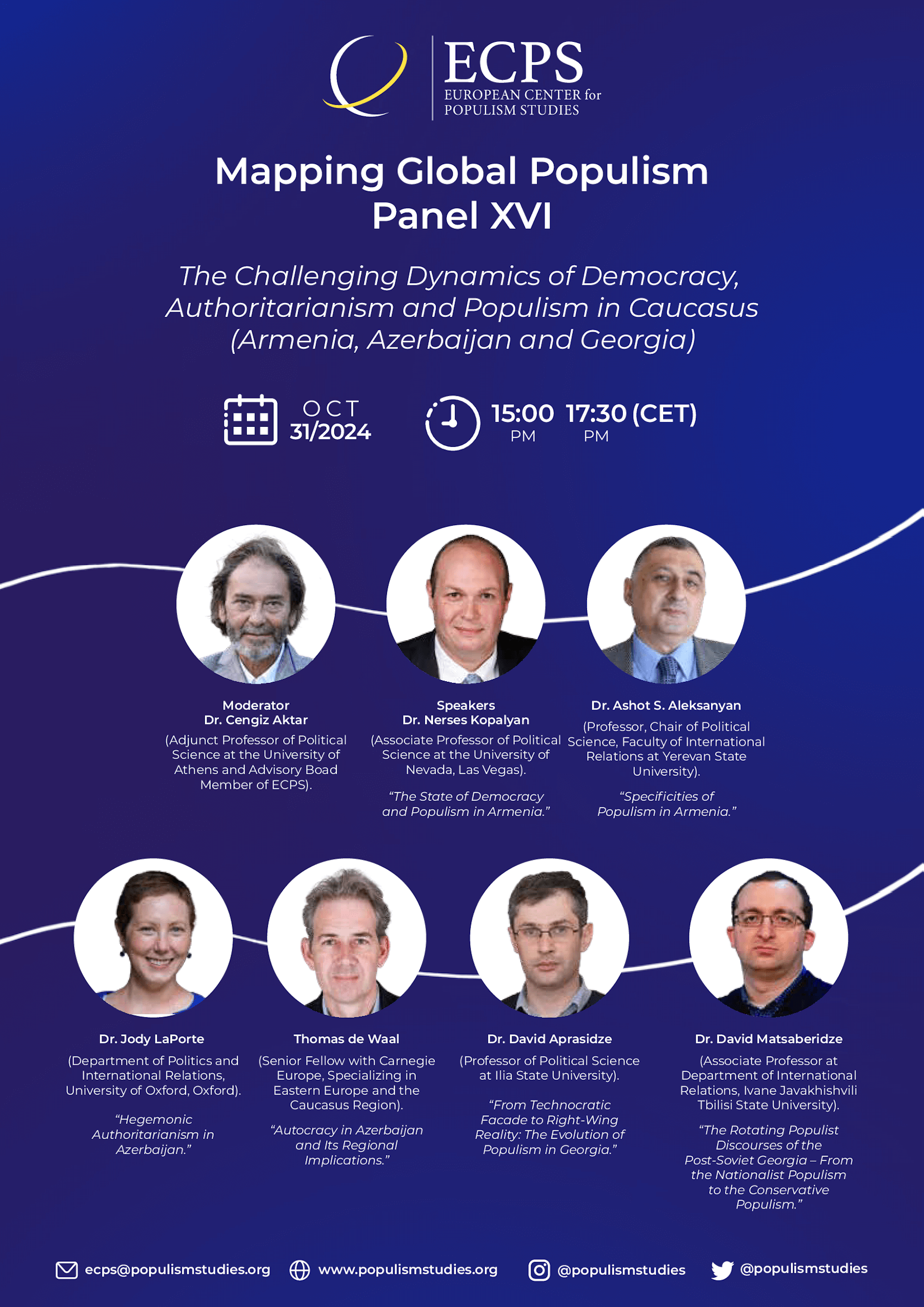

Date/Time: Thursday, October 31, 2024 — 15:00-17:30 (CET)

Click here to register!

Moderator

Dr. Cengiz Aktar (Adjunct Professor of Political Science at the University of Athens and Advisory Board Member of ECPS).

Speakers

“The State of Democracy and Populism in Armenia,” by Dr. Nerses Kopalyan (Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas).

"Populism Against Post-war Armenia’s Democratization and European Integration,” by Dr. Ashot S. Aleksanyan (Professor, Chair of Political Science, Faculty of International Relations at Yerevan State University).

“Hegemonic Authoritarianism in Azerbaijan,” by Dr. Jody LaPorte (Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford, Oxford).

“Autocracy in Azerbaijan and Its Regional Implications,” by Thomas de Waal (Senior Fellow with Carnegie Europe, specializing in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region).

“From Technocratic Facade to Right-Wing Reality: The Evolution of Populism in Georgia,” by Dr. David Aprasidze (Professor of Political Science at Ilia State University).

“The Rotating Populist Discourses of the Post-Soviet Georgia – From the Nationalist Populism to the Conservative Populism,” Dr. David Matsaberidze (Associate Professor at Department of International Relations, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University).

Click here to register!

Bios and Abstracts

Dr. Cengiz Aktar is an adjunct professor of political science at the University of Athens and ECPS Advisory Board member. He is a former director at the United Nations specializing in asylum policies. He is known to be one of the leading advocates of Turkey’s integration into the EU. He was the Chair of European Studies at Bahçeşehir University-Istanbul. In 1999, Professor Aktar initiated a civil initiative for Istanbul’s candidacy for the title of European Capital of Culture. Istanbul successfully held the title in 2010. He also headed the initiative called “European Movement 2002” which pressured lawmakers to speed up political reforms necessary to begin the negotiation phase with the EU. In December 2008, he developed the idea of an online apology campaign addressed to Armenians and supported by a number of Turkish intellectuals as well as over 32,000 Turkish citizens. In addition to EU integration policies, Professor Aktar’s research focuses on the politics of memory regarding ethnic and religious minorities, the history of political centralism, and international refugee law.

The State of Democracy and Populism in Armenia

Dr. Nerses Kopalyan is an Associate Professor-in-Residence of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His fields of specialization include international security, geopolitics, paradigm-building, and philosophy of science. He is the author of "World Political Systems After Polarity" (Routledge, 2017), the co-author of "Sex, Power, and Politics" (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), co-author of "Latinos in Nevada: A Political, Social, and Economic Profile" (2021, Nevada University Press), and the upcoming "Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War (2025, Routledge). His current research and academic publication concentrate on geopolitical and great power relations within Eurasia, with specific emphasis on democratic breakthroughs within authoritarian orbits, and the confluence of security and democratic consolidation. He has authored several policy papers for the Government of Armenia and serves as voluntary advisor to numerous state institutions. Dr. Kopalyan is also a regular contributor to EVN Report.

Populism Against Post-war Armenia’s Democratization and European Integration

Dr. Ashot S. Aleksanyan is Professor and Head of the Chair of Political Science of Faculty of International Relations, as well as Lecturer at the Center for European Studies of Yerevan State University. His main interests are civil society, social partnership, human political rights and freedoms. He has been a DAAD-Visiting Scientist at the Institute of Political Science of Leibniz University of Hannover (2002-2009), DAAD-Visiting Scientist at the Geschwister Scholl Institute of Political Science of Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich (2013) and the Institute for East European Studies of Free University of Berlin (2016), as well as the EU Erasmus Mundus «ALRAKIS» project Visiting Scientist at the Faculty of Social Sciences of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (2012). Since 2016, he is an international fellow of the Institute of Political Science at the Institute of Political Science of the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena.

Abstract: The Velvet Revolution of 2018 and the coming to power of the new prime minister Nikol Pashinyan became a real step towards democratization and deepening of the European political integration of Armenia.

Armenia is a small country and there was great hope that the activities of the new Armenian authorities in relation to the recognized guidelines and standards of consolidation of democracy (separation of powers, independence of the judiciary, transitional justice), it is clear that Pashinyan and his team were able to achieve a breakthrough and are more inclined to adhere to democratic rhetoric.

The 2020 armed conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh lasted from September 27 to November 9, practically shaping a new reality in both foreign and domestic policy dimensions.

The fundamental question is how dangerous is political populism in post-war Armenia? As the example of Armenia shows, unlimited political populism can lead to victims and tragedies on a national scale. What has happened in the state since 2020, and what was for the new authorities of Armenia and Prime Minister N. Pashinyan, as the opposition political parties of the post-war situation wanted to gradually lead the country to political chaos and populism.

After the tragic events of the 44-day war ended, populist movements began to accuse N. Pashinyan of populism, since the promises made to the people during the period of protest activity and the struggle for high office were not fulfilled. This and a number of related factors raise additional doubts and skepticism among members of Armenian civil society who have been observing the activities of the new people’s leader since the opposition’s victory in May 2018.

Since coming to power, the Prime Minister has been repeatedly accused of demagogy. One of the main opponents of the "icon of the velvet revolution" are former Presidents of Armenia Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, who called the Prime Minister a populist.

What factors produced such unprecedented popular unrest to bring to power a new leader who embodied the discontent of the population? It is the hope for a new beginning, where lawlessness will be replaced by the rule of law, injustice by justice, and corruption by honest public officials.

Hegemonic Authoritarianism in Azerbaijan

Dr. Jody LaPorte is the Gonticas Fellow in Politics and International Relations at Lincoln College, University of Oxford. Previously, she served as a Departmental Lecturer in Politics and Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government. Her research focuses on the political and policymaking dynamics in non-democratic regimes, particularly in post-Soviet Eurasia. Dr. LaPorte holds a BA in Russian and East European Studies from Yale University and an MA and PhD in Political Science from the University of California, Berkeley. Before joining the Blavatnik School, she taught as a Departmental Lecturer in Comparative Government in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Oxford.

Autocracy in Azerbaijan and Its Regional Implications

Tom de Waal is a senior fellow with Carnegie Europe, specializing in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region. He is the author of numerous publications, most recently The End of the Near Abroad (Carnegie Europe/IWM, 2024). The second edition of his book The Caucasus: An Introduction (Oxford University Press) was published in 2018. He is also the author of Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide (Oxford University Press, 2015) and of the authoritative book on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War (NYU Press, second edition 2013).

From 2010 to 2015, de Waal worked for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC. Before that he worked extensively as a journalist in both print and for BBC radio. From 1993 to 1997, he worked in Moscow for the Moscow Times, the Times of London, and the Economist, specializing in Russian politics and the situation in Chechnya. He co-authored (with Carlotta Gall) the book Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus (NYU Press, 1997), for which the authors were awarded the James Cameron Prize for Distinguished Reporting.

From Technocratic Facade to Right-Wing Reality: The Evolution of Populism in Georgia

Dr. David Aprasidze is a Professor of Political Science at Ilia State University. He earned his Ph.D. from Hamburg University in Germany and was a Fulbright scholar at Duke University in North Carolina, USA. Over the years, he has worked with public agencies and international NGOs operating in Georgia. His expertise includes higher education management and reform, with a research focus on political transformation, democratization, and Europeanization.

Abstract: In recent years, Georgia has undergone a stark shift from being a champion of Europeanization and democratization to embracing anti-liberal, populist, and pro-Russian stances. The ruling party, Georgian Dream, led by the country’s richest businessman, Bidzina Ivanishvili, has governed since 2012. Initially, Ivanishvili emphasized technocratic governance, managing the state like a corporation. His party portrayed itself as left-centrist, focusing on addressing bread-and-butter issues while also maintaining Georgia’s commitment to European integration. However, amid growing domestic and international criticism for undermining democratic institutions, both Ivanishvili and Georgian Dream shifted toward openly anti-liberal and radical-conservative narratives. This turn included the introduction of anti-NGO and anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, alongside a promotion of "traditional" and "religious" values, supposedly representing the majority. Georgian Dream has forged alliances with right-wing leaders like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and Slovakia’s Robert Fico, but given Georgia’s non-EU status, the country is increasingly aligning itself with Russia. What began as technocratic populism – offering a façade of professionalism to mask authoritarian and oligarchic tendencies – has evolved. Now, Georgian Dream is transparent about its goals: to eliminate political opposition, silence critical civil society, and intimidate the public.

The Rotating Populist Discourses of the Post-Soviet Georgia – From the Nationalist Populism to the Conservative Populism

Dr. David Matsaberidze is an Associate Professor in the Department of International Relations at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Ivane Javakishvili Tbilisi State University. He earned his PhD in Political Science from Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University in 2015 and holds an MA in Nationalism and Ethnicity Studies from Central European University (2008). Between 2015 and 2017, Dr. Matsaberidze completed professional development programs in regional and international security at the George C. Marshall European Centre for Security Studies in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany.

Since 2013, he has been a recurrent visiting expert with the Partnership for Peace Consortium of Defense Academies and Security Studies Institutes at the Austrian Ministry of Defense and Sports (Germany-Austria). From 2008 to 2014, he was a recipient of the Academic Fellowship Program under the International Higher Education Support Program of the Open Society Foundations.

Dr. Matsaberidze has authored 15 academic articles, 8 policy papers in international journals, and 2 books, along with 5 book chapters in English, focusing on democratic transitions, conflicts, nationalism, and security in the post-Soviet Caucasus, particularly in Georgia. His research has been conducted in collaboration with various academic and policy institutions in Germany, Austria, Romania, Serbia, Hungary, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom.

Abstract: The prospective talk will deal with the rotating populist discourses of the post-Soviet Georgia and track the main lines of its transformation from the nationalist populism to the conservative populism. In Georgia, it is taken for granted that political leaders are populists because of their emphasis on charisma and personality. However, although circumstances favored the emergence of political populism and a populist discourse of persuasion was a widespread phenomenon, these developments were neither inevitable nor automatic. The case of Georgia attests that populism as a political discourse typically encompasses the charismatic leader, popular societal demands, strong nationalist component, and the usual affirmation of the common people by the elites and the text and talk of professional politicians, or political institutions, includes both the speaker and the audience. This is not only a discursive mode of making policy, but also shapes the overall political agenda and public opinion, which in turn legitimizes policy decision-making. Therefore, reflecting on discursive practices contributes not only to our understanding of customary political practices, but also to their relationship to the social and political context and its detailed properties, including the constraints on discourse itself.

The post-Soviet Georgian populism is a mixture of populism in policymaking and nationalism in ideology, that allows politicians to control the public discourse and public mind. The first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, was a redemptive populist who wanted to free the Georgian nation from the Russian yoke, thereby responding to the anti-Soviet sentiments of the time. His successor, Eduard Shevardnadze, was a pragmatic populist who restored order and stability to the ransacked nation after the civil war and ethnic conflicts of the early 1990s by introducing a civil society discourse built on democratization and state-building. The third president, Mikheil Saakashvili, was an idealistic populist who used an idealist, pro-Western discourse to renew the Georgian nation through modernization and democratization in the mode of a Western, civic nation. Since 2012, a kind of loss of the national idea can be observed in the political discourse, as the populist discourses of President Giorgi Margvelashvili (2013-2018) and the incumbent prime minister clashed: The former defended the constitutional backbone of the state, i.e., a functioning democratic state for the people, while the latter propagated left-wing populism to restore dignity and ensure the social well-being of the people, which threatens the national idea. The prime minister’s discourse is more widely accepted in society because politics becomes personal in light of a leader who succeeded in defeating the so-called ‘brutal regime’ of the previous government (Ivanishvili vs. Saakashvili). This aspect is a constant feature of the rhetoric of the post-Saakashvili political leadership of the Georgian Dream party.

The conservative-populist turn since 2020 attests the transformation of the foreign policy rhetoric of the Georgian Dream government towards the EUrope. The demarcation-integration cleavages (Kriesi et al., 2008; 2012) appearing in the Georgian society have superseded the traditional Rokkanian cleavages (that have never been consistent in Georgia) and crystalized into the populist radical right-wing direction by the Georgian Dream party: constructing the Georgian people as a cultural unit confined within the Georgian nation-state and through its traditional-conservatist rhetoric indirectly undermining the idea of the regional/EaP European integration, whilst opposing the normative based approach of the EU/Brussels and siding with Orbán’s Budapest, that defends Christianity and traditional-Conservative society. This is the recent strategy of the ruling Georgian Dream, concentrated on politics of radicalization towards domestic (opposition) and external (Brussels) actors through the strategy of alternative or competitive discourse formation, filling in the empty signifier constantly through changing topics and rhetoric(s).

The political discourse of the Georgian Dream sets the new demarcation-integration cleavages: we – Georgia/Georgians – a sovereign nation-state, against any external interference in our will of free choice of domestic and foreign policies (although very vague and not clearly defined), pursued in the interest of the Georgian people (a very populist discourse and rhetoric). The chosen strategy of the Georgian Dream undermines any sort of the whole of society defense system to contain interference of authoritarian regimes in democracies and puts limits on any sort of new democracy promotion project on the Eastern borderlands of the EU, to be driven internally by local actors and supported externally by IOs and CSOs. This undermines any attempt of forming new international resilience via alignment of national resiliencies whose aim is to contain Russian/Eurasian turn to autocracy, while promoting and advancing Euro-Atlantic integration in the EaP countries.