In an interview with the ECPS, Professor Gijs Schumacher of the University of Amsterdam argues that Dutch politics may be entering a “post-populist era.” As the Netherlands approaches yet another general election, Professor Schumacher highlights growing fragmentation across left, right, and radical-right blocs, noting that “many voters no longer perceive meaningful differences between centrist parties.” While populism’s anti-establishment appeal remains psychologically powerful, he observes that this sentiment is now spreading “more evenly across the political spectrum.” According to Professor Schumacher, the Netherlands’ long tradition of elite cooperation could allow a shift toward “pragmatic governance,” provided that “the mainstream left and right tone down their toxic rhetoric.” The post-populist phase, he suggests, reflects not decline but recalibration.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

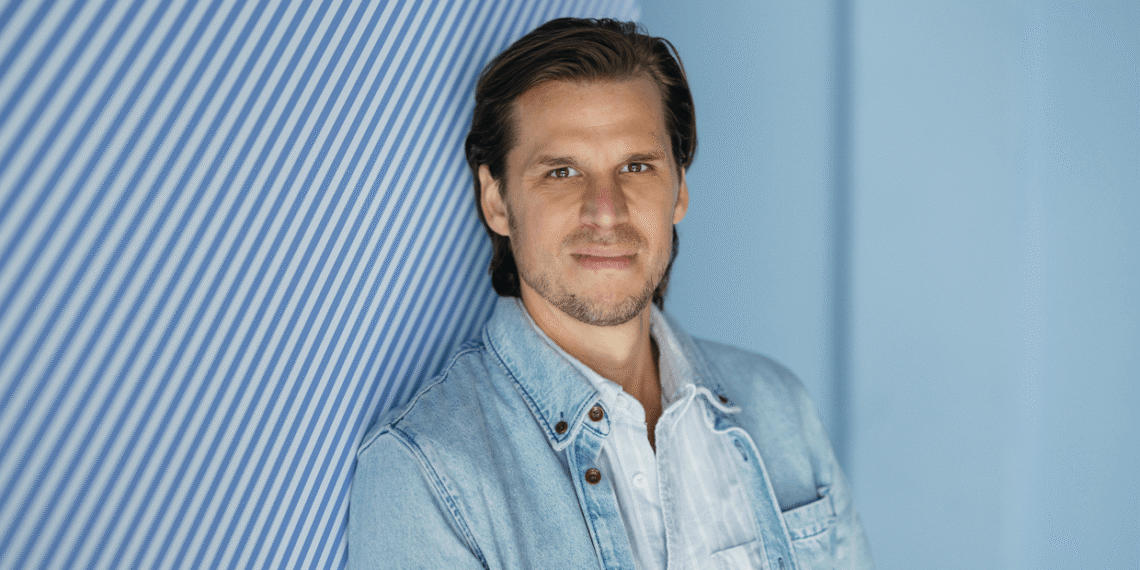

As the Netherlands heads toward its third general election in just five years, the country’s political landscape appears more fragmented and volatile than ever. To understand the deeper psychological and structural undercurrents behind this instability, the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS) spoke with Professor Gijs Schumacher, Professor of Political Psychology in the Department of Political Science at the University of Amsterdam and founding co-director of the Hot Politics Lab. In this wide-ranging conversation, Professor Schumacher reflects on the fragmentation of Dutch politics, the endurance of populist discourse, and what he calls the emergence of a “post-populist era.”

According to Professor Schumacher, the defining feature of contemporary Dutch politics is fragmentation across three major blocs — the left, the right, and the radical right. Yet despite the proliferation of parties, he notes that “people don’t travel much between blocs … the only real possibility for governments is through the middle.” This narrowing of viable coalitional options, he argues, leaves voters disillusioned and searching for alternatives: “Many voters no longer perceive meaningful differences between these centrist parties … and they often end up supporting either other parties within the same bloc or more radical alternatives.”

Populism, Professor Schumacher emphasizes, remains central to understanding this dynamic — particularly its anti-establishment appeal. He observes that this instinct is deeply rooted in human psychology: “It’s a powerful psychological tendency to be skeptical of leadership — to doubt whether those in power are there for your good or their own fortune.” However, Professor Schumacher points out that the Dutch left has largely abandoned its own anti-establishment roots, creating a political vacuum that figures like Geert Wilders have exploited: “Historically, the left had a strong anti-establishment agenda … but in opposing the populist radical right, they’ve completely muted that stance.”

Despite this, Professor Schumacher does not foresee a permanent populist capture of Dutch democracy. Instead, he suggests the country may be entering what he calls a “post-populist era” — a phase in which anti-establishment politics no longer belongs exclusively to the radical right but becomes “more evenly distributed across the political spectrum.” In his words: “The Netherlands has a long history of deep affective polarization — even though we didn’t use that term at the time — but it was never a major problem because, at the elite level, there was greater cooperation. The mainstream left and right don’t need to fight each other; there’s little to gain from it. If their rhetoric were less toxic, there would be no real barrier to a return to pragmatic governance.”

For Professor Schumacher, this shift signals neither a triumph of populism nor its total eclipse but rather a recalibration — a search for equilibrium in a political system that remains both fragmented and remarkably resilient.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Gijs Schumacher, revised for clarity and flow.

Non-Policy Issues Now Matter Much More

Professor Gijs Schumacher, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: As the Netherlands approaches its third general election in just five years, how would you characterize the current political landscape? What structural and psychological factors — fragmentation, voter volatility, or declining partisan loyalty — best explain this ongoing electoral instability?

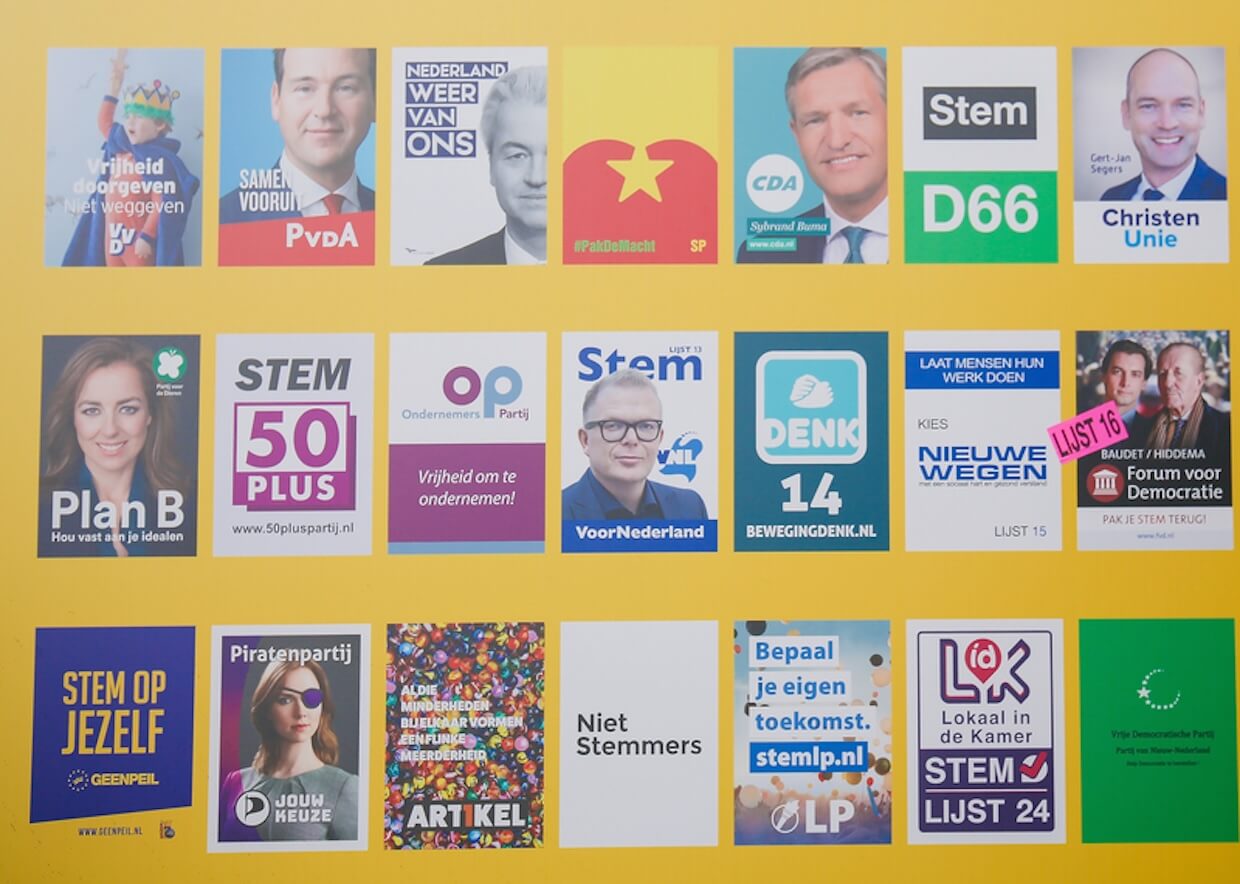

Professor Gijs Schumacher: The best characterization is indeed fragmentation. If you look at the party system, there are, roughly speaking, three different blocs of parties: the left bloc, the right bloc, and the radical right bloc. The last bloc has grown the most over the past 10 to 20 years, but there’s also a great deal of fluctuation within it.

In fact, there’s a lot of fluctuation across all the blocs. However, on average, people don’t move much between them. In that sense, voters tend to shift from one right-wing party to another, or from one left-wing party to another. Ultimately, the only real possibility for forming governments lies in the middle — between the left and the right.

The problem with that is that many voters no longer perceive meaningful differences between these centrist parties. This frustrates them, and they often end up supporting either other parties within the same bloc or more radical alternatives. Of course, the last government was an exception to this, as it was a right–radical right coalition, but it was so short-lived that, in a sense, it only demonstrated how difficult such a government would be.

If you ask about the psychological characteristics — that’s a very complex question. One key factor is that voter loyalty is very low. In contrast to the 1980s, people identify far less with a particular party and therefore move more easily between them. Voters today are less loyal, which is not necessarily a bad thing; you could also say they’re more critical.

Because there are multiple parties that are ideologically close to each other within each bloc, and because there is competition within blocs, non-policy issues start to matter much more — things like how a particular leader performs in election debates or in the media. Do we like this party because they were in government, or not? These considerations are becoming increasingly important compared to policy-based reasons.

Overall, this calls for a research agenda focused on political psychology — one that specifically studies these non-policy-related factors. I think the leader of D66 put it quite aptly — although I’m not entirely sure whether he meant it ironically — when he said: “Policy is less important; it’s more about the vibe you’re getting with a party.” That’s exactly the point. But what is this vibe? How can we study it? How can we analyze it?

The PVV Leads a Parade of Dwarfs

Despite Geert Wilders’ authoritarian leadership style and his role in repeated government collapses, the PVV continues to lead in the polls — how do you interpret this enduring voter support, and what does it reveal about Dutch citizens’ tolerance for personalist populism and their affective attachment to strong, anti-establishment leadership?

Professor Gijs Schumacher: Yes, they are the party leading the polls, but it’s basically leading a parade of dwarfs. All the parties are small now. So, the size that the PVV has in the polls — about 30 seats, or 20% of the vote — is actually a very low number for the largest party. I sometimes like to turn it around. I don’t think the question is why the radical right is so large, but why the middle is so small. Because in the middle, the centrist parts of the left-wing and right-wing blocs — there are parties that are very similar. If you added their votes together, they would be much larger than the Freedom Party. It’s just that they choose not to join hands in these elections, and that’s why they end up as the second, third, or fourth party. Now, there’s one footnote to make: for the second time, they are running with a joint list, and also, formally, these parties are on track to merge with each other. Still, there are many other parties they could potentially merge that are ideologically quite close.

Then, more specifically about Wilders. There’s something about populism that is extremely powerful psychologically, and that’s the anti-establishment aspect. There are other things that are also psychologically very powerful about populism, but I want to focus on this one because I think it’s important. An anti-establishment stance is one of the defining features of populism, and this is very firmly rooted in human psychology — to be critical of leadership, skeptical even, doubtful whether the people in power are actually there for your good or for the general good, as opposed to their own personal fortune. That’s a very powerful human psychological tendency, and it’s actually a very good one. It has been an extremely important feature of the survival of humans as groups.

The Left Has Abandoned Its Own Anti-Establishment Agenda

So, the question I want to raise is this: one of the problems of the left and the right blocs — particularly the left-wing bloc — is why they have dropped their own anti-establishment agenda. They have adopted the position of being the power. In the Netherlands, the media continuously speak of the “left-wing media” or the “left-wing church,” as they call it. This “left-wing church” is supposedly so influential, but it doesn’t make any sense — the left barely has a third of the votes. They don’t get more airtime or anything. And the left adopts this narrative, accepting its role as being elitist. That makes for a very strange political dynamic because they’re not the elite, they’re not in government, and they haven’t been in government for a while. They’re not particularly politically powerful. Historically, the left has always had a very strong anti-establishment agenda — for example, critiques of capitalism — and this now seems so muted. In their opposition to populist radical right parties, they have completely abandoned their own anti-establishment stance, and that’s really a pity because it’s a powerful psychological force that really sways voters. Therefore, part of this group of people is really moved by this anti-establishment approach to politics.

Now, the other reason why they face large support is through another mechanism — that’s the more authoritarian, anti-immigrant type of agenda. There’s always been strong support for anti-immigration policies in the Netherlands. In that sense, there’s been absolutely no change since the 1990s. The difference is that political parties are now doing something with it. This already started in 2001 with the rise of Pim Fortuyn, so it’s not new at all. The only new thing is the degree to which mainstream parties are also adopting anti-immigration stances. By doing so, they legitimize the radical right and make it more normal, which also affects voters. The party becomes less tainted, and people become more likely to vote for it.

So, it’s really this mix — on the one hand, the anti-establishment stance, and on the other, authoritarianism — that makes the party popular. But it’s not necessarily the same type of people. It’s the combination of one group that finds the authoritarian route appealing and another group that is in the anti-establishment camp. If you want to think about how we can systematically change the distribution of votes across these three blocs, then my suggestion would be to look in the anti-establishment direction.

Affective Contagion Works Differently in Politics

We have seen the normalization of populist rhetoric across the political spectrum — from immigration and national identity to housing and cost of living. To what extent do you think populist narratives now define the terms of political competition in the Netherlands? Are mainstream parties engaging in what you’ve described as “affective contagion” from populist discourse?

Professor Gijs Schumacher: That’s a good question. So, starting with how pervasive populist narratives are in politics — I think they’ve always been there, and they’ve been present on both the left and the right. I’m particularly referring to anti-establishment stances. I mean, D66, one of the most centrist parties in the Netherlands, emerged from a populist agenda — a very strong anti-establishment position. Some of that critique is still there, but much of it has been watered down or disappeared from their platform. Populist narratives are always pervasive, and sometimes also very useful, because they can bring about innovation in the party system — which is a good thing. When we talk about representation, sometimes old ideas need to go, and new ideas need to enter. It also means, of course, that sometimes bad ideas enter the political system — that’s also true.

If we talk about anti-immigration policies, as I already mentioned earlier, the party system has shifted toward a much more critical stance than before. People are associating problems with housing and immigration. But that’s really just the radical right; I don’t see other parties making that argument. It’s interesting in this election that the Farmers’ Party, which started a few years ago really trying to represent agricultural interests, has now completely adopted radical-right rhetoric as well. But, they were already in the radical-right camp, so that’s not surprising. For a while, they looked like a more centrist alternative, but they turned out not to be.

To put it differently, I do think a lot of politicians believe it’s necessary to talk about immigration because there’s a strong idea that it’s the most important topic in the elections. The thing is, though, that this idea is not true. If you ask Dutch citizens what the most important issues are in Dutch politics, you get a whole list of issues — and they are all equally important. The problem is that there’s a lot of fragmentation in the answers. Lots of people find different issues important: cost of living, housing, climate change, the international situation, and immigration, of course. In that sense, the populist narrative around immigration has been extremely successful — in the sense that media and politicians believe they need to talk about it so much.

Now, whether there’s affective contagion — it’s funny that you use this term in this context, because the word affective contagion comes more from interpersonal psychology. It’s about whether the emotion of person A is adopted by person B, who is listening to person A. In politics, the model of affective contagion is very complex because whether I take over the emotion that person A has depends very much on what my beliefs are about person A. So, if person A is a politician from a party I like, I will probably listen more carefully. If person A is a politician from an out-party, I will be incensed, angry, or upset. I will actively try to think about arguments for why this person is talking nonsense.

But there’s also another, slightly different, and older use of the word — one that comes from earlier work on political parties in sociology: “contagion from the left.” The idea was that right-wing parties adopted all kinds of ideas from left-wing parties in the early 20th century. For example, the mass organization of left-wing parties was adopted by right-wing parties as a way to counter the electoral threat of the left.

So, if you interpret contagion in this sense, then without a doubt, the Dutch political system has been very much influenced by the success of different radical-right parties in the Netherlands — LPF, PVV, initially also the so-called Leefbaar parties, and, of course, the latest ones like Forum for Democracy and JA21.

The Debate Fixates on Asylum Seekers Instead of Real Solutions

Housing shortages, migration management, and rising living costs dominate the campaign. In your view, how do these issues interact with emotional and identity-based appeals in shaping voter preferences? Are material concerns or cultural grievances more decisive in the current moment?

Professor Gijs Schumacher: Yes — that’s the short answer. In the Netherlands, the traditional left–right economic dimension has effectively collapsed into a largely cultural one.

When it comes to housing, the problem with the immigration debate is that there are many different forms of immigration. Typically, the type that is politically sensitive involves asylum seekers — and that’s what all the fuss is about. People don’t want to have a center in their municipality where asylum seekers are housed.

That’s what the PVV rallies behind: reducing asylum seekers. But this group represents a very small share of total immigration — I think only a few percent. So even if we somehow magically got rid of asylum seekers, we would still have massive immigration.

The point is that other forms of immigration — for example, seasonal immigration — make up a large share. There are many seasonal immigrants in the Netherlands; in fact, the entire agricultural sector essentially depends on them. They’re not politically problematic because the right doesn’t want to make an issue out of them — the companies that support these parties need these workers and can’t do without them. How would our apple farms function — how would those apples be picked — if there were no people from Eastern Europe coming here? The same goes for asparagus and other high-value vegetables.

And then there’s, of course, the more “expat” type — high-profile professionals with high salaries coming in, particularly to Amsterdam for well-paid jobs. Nobody’s complaining about them in any cultural sense, although their impact on the labor market is much greater than that of asylum seekers. Here in Amsterdam, housing prices are also extremely high because of people coming from abroad — people who receive relocation allowances from their companies and can therefore outbid Dutch buyers. But that’s not how the discussion is framed. The focus is on asylum seekers. So, it’s a really strange — or rather, a really striking — discussion in the sense that the way it is shaped isn’t meaningfully directed toward the real solution.

Voters Now Choose Parties Like Beers in a Bar

Given the widespread refusal of other parties to enter a coalition with Wilders, yet his continued dominance in the polls, what does this suggest about the representational capacity of the Dutch party system? Are we witnessing a deepening crisis of coalition politics — or an evolution toward a new equilibrium shaped by populist pressure from the margins?

Professor Gijs Schumacher: There are two things. About 20% — or maybe a bit more — goes to Wilders. But also, something like 20% goes to about eight political parties that each have just a few seats. And then you’re left with 60% of large dwarfs, let’s call them that. That’s where the coalition mostly needs to come from. So that makes it super complicated. It basically means the traditional large Dutch political parties — the Christian Democrats, Labour (now merged with the Green Party), and the Liberal Party, VVD — essentially need to cooperate. So, you get these governments that are well known in Germany as “Grand Coalitions.” But we also know from those experiences that these governments are always very unpopular because people don’t really see differences between the parties anymore. Then again, this gives rise to splinters — or not-so-small parties now, actually — on both the left and the right.

But the question is: what is the representational capacity of the Dutch party system? If we define that as the distance between the party you vote for and what that party stands for, then with so many parties, you actually have excellent representational capacity. In terms of government policy, you would just have something in the middle, which would always be relatively close to a large group of people. The problem lies in the manageability of such large coalitions — large both in terms of the number of parties and the range of policy differences between them.

Secondly — coming back to the point about the “vibes” that I mentioned earlier — Jock Robiette, the leader of D66, once said that vibes are the reason people vote for parties. I agree with him. Vibes are very important, but they’re a distraction from representational capacity because they have little to do with policy, to some extent. In the Netherlands, it sometimes feels like voters are in a supermarket or a bar, handed a list of 25 different kinds of beer. They spend a long time thinking about which specific type to choose — a New England IPA or a double IPA? That’s the kind of choice Dutch voters are making now. But, of course, politics isn’t a bar. You need to combine beers to get a majority. That’s where the real problem lies.

The Party Landscape Has Changed Too Much to Compare Over Time

Based on your work on affective polarization, do you observe rising emotional hostility between Dutch party blocs — or is the Netherlands still characterized by pragmatic, cross-partisan attitudes?

Professor Gijs Schumacher: I’m not sure whether this is increasing or stable over time. It’s actually a pretty tricky research question because the parties themselves change over time. For example, if you go back to 2010, there was no Forum for Democracy, no JA21, and the PVV had basically just started — it was a very minor party. So, if we had asked in 2010 what people felt about different political parties and compared it to now, when we have all these parties that are much more radical, you can’t really compare the two periods.

That makes it difficult to know for sure whether affective polarization is actually increasing. In general, I don’t think the Netherlands is all that dramatic in this regard. Everybody hates the radical right — that’s almost the uniting factor. What has been more problematic is that the right —mainly the Liberal Party — has been polarizing by labeling Labour–Green as a radical extremist party, which, by any standards, it’s not. By introducing this kind of language — and of course, what politicians say has an effect on people — they may cause voters to become more polarized and more hostile toward the left.

The PVV Relies So Heavily on One Person That It Can’t Grow Strong

Wilders’ one-man party structure is unique in Western Europe. How does this extreme centralization of authority affect voter perceptions of accountability, competence, and representation?

Professor Gijs Schumacher: I think the real problem with the PVV is that, since it relies so heavily on a single person, it struggles to become a genuinely strong and influential party. Essentially, its only way to influence politics is by shouting bizarre things — and, in fact, that works quite well for them. But the party lacks the capacity to effectively propose or implement policies that could actually address the issues it highlights.

This weakness stems from the fact that the PVV is structurally too weak. It has no detailed policy proposals beyond slogans like “all foreigners out.” When they are in government, they basically have to rely on civil servants to come up with plans to execute this — which, of course, is complicated and slow. Then they end up blaming the civil servants for blocking their ideas. But a good political party would not only have a slogan but also a set of coherent policies to realize it. The PVV simply doesn’t have this to any meaningful extent.

The second problem is the training of talent. Traditionally, political parties were expected to develop policy ideas through their connections to civil society, but the PVV doesn’t do that either. When they had ministers for the first time, almost none of them had any executive experience — perhaps none at all — and it was evident. The Minister for Immigration, for instance, had real difficulty even hiring a spokesperson. They couldn’t manage the most basic tasks.

That was really problematic. If you look at Wilders’ list, you’d expect his ministers or vice ministers — the most recognizable figures after him — to be ranked high. They’re not. The most prominent one, Ahmed, isn’t even on the list. De Vries is placed somewhat lower, and Madlener is also very low. This was hardly a vote of confidence in them. We’ve seen many times in the PVV that whenever someone begins to stand out, their head immediately comes off — and that person ultimately leaves the party. So, yes, this is a real problem. The PVV does represent a segment of the Dutch population, but if it cannot effectively formulate and implement policy, then the issues its voters care about will never truly be addressed.

If Rhetoric Were Less Toxic, Pragmatic Governance Could Return

And finally, Professor Schumacher, do you see the Netherlands as entering a post-populist phase where affective polarization stabilizes and institutional pragmatism returns, or are we witnessing a longer-term transformation in the emotional foundations of Dutch democracy?

Professor Gijs Schumacher: I think we’re moving into a post-populist era. If anything, we might be entering a phase where anti-establishment politics becomes more evenly distributed across the entire political spectrum, rather than being concentrated mainly on the radical right.

The Netherlands has a long history of deep affective polarization — even though we didn’t use that term at the time — but it was never a major problem because, at the elite level, there was a greater degree of cooperation. And that’s ultimately where the goal should lie.

The mainstream left and right don’t need to fight each other; there’s little to gain from it. They’re not going to win many more votes that way. If their rhetoric were less toxic toward one another, there would be no real barrier to a return to pragmatic governance.