Please cite as:

Havlík, Vlastimil & Kluknavská, Alena. (2024). “The Race of Populists: The 2024 EP Elections in the Czech Republic.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0066

DOWNLOAD REPORT OF CZECH REPUBLIC

Abstract

The chapter analyses the performance of populist political parties in the 2024 EP election in the Czech Republic. The election ended with a significant increase in support for several populist parties: Action of Dissatisfied Citizens, Freedom and Direct Democracy and the Oath and Motorists. All populist parties used radical-right rhetoric before the election, expressing different levels of criticism of the European Union, strong anti-immigration attitudes and negative attitudes toward the Green Deal. The preliminary data show that the electoral support for the populists was based on a higher level of mobilization in so-called peripheral areas of the Czech Republic, potentially affected by recent inflation and austerity policies pursued by the government. All in all, the 2024 EP election in Czechia significantly increased support for populist political parties.

Keywords: populism; Czech Republic; Euroscepticism; far right; radical right

By Vlastimil Havlík* (Department of Political Science, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic) & Alena Kluknavská** (Department of Media Studies and Journalism, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

Introduction

The EP election took place three years into the Czech Republic’s four-year parliamentary electoral cycle, making it an important test of support for both governing parties and the populist opposition. After the 2021 general elections, five political parties built two electoral coalitions, both of which advanced an anti-populist platform: the right-wing Spolu (Together) and the centrist coalition between the Pirates party and Mayors and Independents (Starostové a Nezávislí, STAN). They agreed to form a new government, effectively ending eight years of governments with a significant populist presence.

Yet populists made a comeback in the 2024 EP election. The campaign leading up to the 9 June polls was dominated by the issues of immigration and the European Green Deal, and all the populist parties tried to frame the election as a referendum on the incumbent government’s performance. Historically, in line with the second-order elections theory (Reif & Schmitt, 1980), Czech voters have often taken elections as an opportunity to punish the government by voting for the parliamentary opposition or even for new political parties (Charvát & Maškarinec, 2020). The 2024 election did not depart from this trend, and populist parties came out on top: besides two ‘established’ populist parties – Action of Dissatisfied Citizens (ANO) and Freedom and Direct Democracy (Svoboda a Přímá Demokracie, SPD) – the electoral coalition of the populist ‘Přísaha a Motoristé’ (Oath and Motorists, AUTO) gained representation in the European Parliament. While many voters may have voted for populist parties out of frustration with national politics and the incumbent government’s performance (Mahdalová & Škop, 2024), the message to the European Parliament from the Czech Republic is unequivocal: populist voices are stronger and more radical than ever before.

Background

Similarly to other European countries, the Czech Republic has witnessed a proliferation of populist political parties over the past 15 years. This expansion has been precipitated by the 2008 economic crisis and a series of political scandals, which have resulted in a decline in support for the established political parties (Havlík, 2015). The largest populist party, consistently polling around 30% of the vote, is ANO, founded in 2011 and led by the billionaire industrialist Andrej Babiš. The party is typically characterized as a technocratic or centrist populist party lacking clearly defined ideological foundations. The party initially gained traction by appealing to voters through an emphasis on communicating expertise and the ability to run the state effectively while blaming the established political parties for incompetency and corruption (Havlík, 2019).

However, it has recently shifted both rhetorically and electorally towards the economic centre-left combined with nativist and authoritarian attitudes, moving closer to the programmatic formula typical for other far-right political parties in contemporary Europe (De Lange, 2007).

ANO initially became part of the coalition government in 2013 as a junior partner to the Social Democrats (SPD) and the Christian Democrats. Following the 2017 election, it became the leading government party in a minority coalition with the SD, which was supported for the majority of the term by the communists (Komunistická Strana Čech a Moravy, KSČM). After the 2021 general election, ANO assumed the role of the leading opposition party. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the party adopted a stance of ambivalent support for Kyiv while simultaneously advancing a criticism of Ukrainian policies as well as welfare-chauvinist arguments (i.e., the idea that welfare benefits and social services should be reserved primarily or exclusively for the native population of a country, rather than being extended to immigrants or non-citizens) (Havlík & Kluknavská, 2023). Additionally, it has taken a pro-Israel stance during the Israel–Hamas conflict.

Concerning its position towards the EU and EU policies, ANO has shifted from a mildly pro-European stance (Havlík & Kaniok, 2016) towards soft Euroscepticism over time. Initially, the party defended Czechia’s membership of the EU, and Babiš even offered lukewarm support for the country adopting the euro. Subsequently, ANO began to emphasize the need to safeguard Czech national sovereignty vis-à-vis the EU, utilizing anti-elitist populist rhetoric targeting ‘European elites’ and attributing the EU’s ineffectiveness in migration policy to incompetence in Brussels. The party’s stance towards the EU became increasingly aligned with that of populist radical-right parties in other EU member states.

In its manifesto for the 2024 European Parliament election, ANO adopted a clear intergovernmentalist position, presented in a populist manner. It called for the ‘need to restore the decisive role of the national states in the EU’. It also opposed decisions taken by European institutions and ‘non-elected bureaucrats’ who are ‘disconnected from the reality of everyday life’ (ANO, 2024). The party criticized the EU Pact on Migration, framing it as a security concern and warning the Czech Republic not to ‘take the path of Western Europe, where no-go zones have sprung up in many cities, where people are afraid to go out at night, and women are at risk of violence’ (ANO, 2024). ANO also promised to reform the European Green Deal passed ‘in defiance of common sense’, claiming that ‘Brussels has decided to commit ritual suicide’ (ANO, 2024). ANO rejected the idea of the ban on combustion engines and even dedicated a chapter in its manifesto to the issue, contributing to the high salience of the issue in the electoral campaign. ANO also criticized the EU for the supposed ‘restrictions on freedom of expression that are now taking place under the guise of fighting disinformation. In reality, however, this term often masquerades as the EU’s desire to regulate and restrict the publication of alternative opinions’ (ANO, 2024). Even more, ANO blamed ‘both domestic and Brussels elites’ for ‘wanting to control, dominate and re-educate people in various ways’ (ANO, 2024), comparing it to the oppression of human rights and freedom during the communist regime before 1989.

SPD is a populist radical-right party led by Tomio Okamura. The party, along with its predecessor, Dawn of Direct Democracy (also founded by Okamura), has been represented in the national parliament since the 2013 general elections, consistently garnering around 10% of the vote. The party’s initial success was tied to Okamura’s popularity as a TV personality (he was president of the Czech Association of Travel Agencies, performed in a reality show, and gained media attention with his project of a toy travel agency). The party has capitalized on its potent anti-establishment appeal and, with the onset of the immigration crisis, adopted xenophobic, uncompromisingly anti-immigration and hard Eurosceptic rhetoric. SPD has become one of the most vocal anti-Ukrainian voices following Russia’s 2022 invasion (Havlík & Kluknavská, 2023). Due to its anti-Islam stance, SPD has been a stalwart defender of Israel during the Israel–Hamas conflict. Unlike ANO, SPD has never been part of the government.

In mid 2023 SPD formed an electoral alliance with Tricolour, another populist radical-right outfit, ahead of the 2024 EP elections. The two parties continued to co-operate in the run-up to the polls. A first glance at SPD’s EP manifesto reveals a striking similarity with ANO’s rhetoric. The major difference lies in SPD’s more radical language, a generally more sceptical attitude towards the EU (including a demand for a membership referendum), and a stronger emphasis on immigration policy. SPD was highly critical of the EU, describing it as a ‘dictatorship in Brussels’ dominated by ‘non-elected bureaucrats’ who produce ‘directives that are against the interests of our state and our people’ (SPD, 2024).

The party framed the issue of migration primarily in security terms, rejecting the EU Pact for Migration, claimed that the EU supports ‘mass migration and multiculturalism’, and stated that ‘[m]any Western European cities have already been Islamised, resulting in huge crime, terrorism, and the domination of Sharia law in so-called no-go zones’ (SPD, 2024). SPD also rejected the Green Deal, vehemently opposing ‘any attempt to reduce car transport and combustion engines’ (SPD, 2024). The party criticized political correctness, accusing the EU of censorship and a disingenuous campaign against disinformation. Overall, among the Czech political parties represented in the EP, SPD was closest to ‘hard Euroscepticism’, challenging the current trajectory of the EU and even questioning the Czech Republic’s membership.

In addition to the existing populist political parties with representation in the Czech parliament, several new populist radical-right parties have emerged since the 2021 election. These parties have capitalized on discursive opportunities related to the high level of inflation (at times the highest among EU member states), the government’s austerity policies, and, to some extent, the war in Ukraine. In 2022, Jindřich Rajchl, a former member of Tricolour and an organizer of anti-COVID-19 measures demonstrations, founded the Law, Respect, Expertise (Právo, Respekt, Odbornost, PRO) party. Rajchl co-organized several anti-government demonstrations, the largest of which drew around 70,000 participants. However, he and his party lost momentum as the Czech economy gradually recovered and public support for pro-Russian stances remained limited.

Conversely, the political party Oath, founded in 2021 by former police chief Róbert Šlachta, whose anti-organized crime unit led a corruption investigation that toppled the right-wing cabinet in 2013, stabilized its support. Despite receiving 4% of the votes in the 2021 general election and polling below the 5% electoral threshold, the party saw an uptick in support before the election, according to some opinion polls. One reason for the increasing support was the electoral coalition Oath formed with Motorists for Themselves (formerly named Referendum on the EU, later the Party for the Independence of the Czech Republic).

The coalition leveraged the opportunity to campaign against the government, took an anti-immigration position and strongly criticized the European Green Deal, especially the planned ban on cars with combustion engines. Although many political parties made similar claims, the coalition gained credibility in the fight to preserve combustion engines by placing Filip Turek, a former racing driver, luxury car collector and social media influencer, at the top of its electoral list. Despite consistently polling around 5%, the coalition saw a growth in support shortly before the election. Some analysts attributed this boost to Turek’s increased media visibility, which included allegations of his use of Nazi symbols (which Turek downplayed) and the fact that the party and Turek himself became a target of negative campaigning from some of the government and opposition parties. For instance, the electoral leader of Mayors and Independents, one of the government parties, challenged Turek to a TV debate, framing him as a major threat to Czech democracy. This debate, which took place just a few days before the election, recorded significant viewership and may have impacted the result of the party in the election.

Electoral results

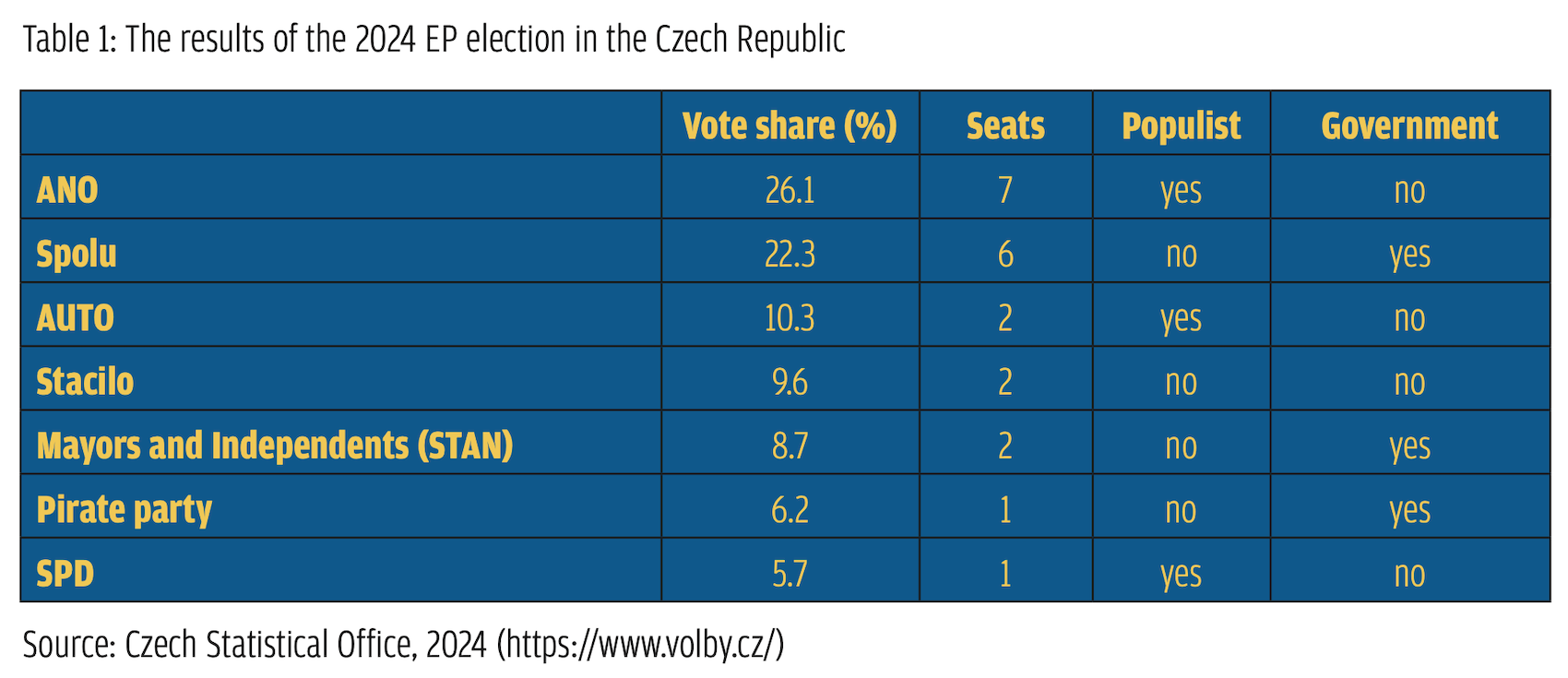

Populist parties gained 10 of the 21 MEP seats allocated to the Czech Republic. ANO took poll position with 26.1% of the vote (electing seven MEPs), increasing its support by 5 percentage points compared to the 2019 EP elections. The SPD and Tricolour list secured 5.7% of the votes and one seat, a decline of more than 3 percentage points compared to 2019. The biggest surprise of the election was the 10.3% of the votes and two seats won by AUTO. By including the votes received by other protest parties, such as the coalition Stačilo (Enough) led by the KSČM, with those received by populist parties, the protest camp secured a majority of 55% of the votes.

Despite the government’s low popularity, the incumbent parties scored relatively well, collectively gaining almost 37% of the votes (compared to 43% in the 2021 general election). The right-wing Spolu coalition (22.3% and 6 MEPs) achieved a fair result, and Mayors and Independents (STAN) met the expectations set by the public opinion polls (8.7% of votes and 2 MEPs). Among the governing parties, only the Pirates performed poorly (6.2% and 1 MEP). The election did not signal a revival for the SPD, once a defining pole in the party system. Having remained just below the electoral threshold in the 2021 general election and losing parliamentary representation after more than 30 years, the SPD received less than 2% of the votes, continuing their decline into irrelevance.

As with the previous EP elections in Czechia, the results were marked by low electoral turnout. However, turnout increased significantly to 36%, the highest in the history of EP elections in the Czech Republic (up from 29% in 2019). According to an analysis of aggregated data published shortly after the election, the increase in turnout was likely linked to mobilization in peripheral areas, including the so-called inner peripheries (Grim, 2024). These are less developed areas with lower levels of infrastructure, higher unemployment and a higher proportion of low-educated people. It should be noted that peripheral status is not defined exclusively by economic factors; it also has vital historical, social, and cultural dimensions (Bernard & Šimon. 2017). Previous studies have shown that people living in peripheral areas are more likely to hold populist attitudes (Dvořák et al., 2024), and populist parties tend to be more successful in areas characterized by economic hardship or an ageing population (Dvořák & Zouhar, 2022; Lysek et al., 2021). Early analyses of the aggregated data indicate that the 2024 EP election followed this pattern. ANO, AUTO, SPD and Stačilo were most successful in the peripheral areas. The notable results of ANO, which benefited the most from increased turnout in these areas, confirm the transformation in the character of support for the once-centrist populist party (Havlík & Voda, 2018). The success of populists in the areas may stem from the harsh impact of the recent inflation and austerity policies introduced by the government on the people living in peripheral areas. However, historically, the peripheral regions have always been more critical of the EU, and their Euroscepticism may also have played a notable role (Plešivčák, 2020).

Data from opinion surveys conducted a few weeks before the election reveal important similarities and some differences in the socio-demographics of the electorates of the three populist parties that crossed the electoral threshold. Support for ANO spanned various socio-demographic groups but primarily relied on voters without high school diplomas (37% declared they would vote for ANO) and those aged 60 or older (34%). Conversely, only 9% of voters with a university degree and 11% of those aged 18–29 supported ANO. SPD supporters were mostly men and individuals with elementary education, with younger voters less likely to support SPD compared to those aged 45–59. Due to the small number of respondents supporting AUTO, identifying a clearer voter profile is challenging, although there was slightly higher support among men and younger voters (STEM, 2024).

Despite the lack of data on the ideological profiles of populist party voters, it is evident that, on average, populist parties were more attractive to less educated voters and were more successful in peripheral areas. The spatially uneven growth of electoral turnout suggests that the overall rise of populist parties can be attributed to higher mobilization in areas favourable to them. Nevertheless, the differing changes in support for various populist parties (notably the growth of AUTO and Stačilo versus the decline of SPD) indicate limited spillover across government and opposition camps. The ‘populist race’ is further evidenced by data from another pre-election opinion poll, where voters were asked to cast votes (preferences) for two parties. Only a limited number used ‘split votes’ in the sense of supporting one populist (opposition) party and one governing party. This finding relates to the high level of political polarization between populist and anti-populist forces recently observed (Hrbková et al., 2024). In other words, the results of the EP election in Czechia point to the ongoing transformation of the party system from a relatively stable unidimensional competition between the left and the right into a contestation between populist and anti-populist forces (Havlík & Kluknavská, 2022).

Discussion

The EP election in Czechia has resulted in a majority of votes for populist (and protest) parties. Despite their ideological differences, all of these parties share a critical attitude towards the supranational principles underpinning the EU’s functioning and call for strengthening the role of national states in the EU decision-making process. SPD even advocates a reconsideration of Czech membership in the EU. Consequently, Czech populist parties will likely oppose any attempts to strengthen the powers of supranational EU institutions. Similarly, their criticism of the Green Deal and the regulation of cars with combustion engines suggests they will seek to revise the legislation or at least slow down its implementation.

However, the success and real impact of the Czech populists at the EP level will be affected by their membership in EP groups. Given ANO’s ideological shift and the departure of its former liberal pro-European MEPs, ANO decided to leave the liberal Renew group and initiated the formation of a new populist radical-right Eurosceptic group, Patriots for Europe (PfE) alongside Fidesz and the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ). Despite AUTO expressing their willingness to join the European Conservatives and Reform group (ECR), the governing Civic Democratic Party (ODS), one of the ECR’s founders, did not support its inclusion, and AUTO eventually joined PfE. Although ANO and AUTO have become members of the third-largest EP group, which includes parties such as France’s far-right National Rally (RN), the Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang, VB), Spain’s Vox or Italy’s Lega, the first votes in the EP have already indicated that the PfE’S influence on policy in the current legislature will be constrained. For example, PfE representatives have been excluded from the allocation of posts in EP committees). SPD, the most radical populist party, formed a new far-right Europe of Sovereign Nations group (ESN) alongside the Alternative for Germany or the French Reconquest. ESN is the smallest of the EP groups in the 2024–2029 legislature, and – similarly to PfE – the EP majority has applied a cordon sanitaire to the group, significantly reducing the effective power of ESN in the EP.

The results of the 2024 election in Czechia indicate a strengthening of the populist radical-right and Eurosceptic voices in the EU. First, AUTO gained representation in the EP as a new populist radical-right party. Second, the share of MEPs held by populist parties increased compared to the previous EP elections. Third, given the radicalization of ANO’s ideology and its elected MEPs, the populist voices from Czechia will be more Eurosceptic and generally more radical than ever before. Although their membership in EP groups outside the mainstream of EU politics may tone down the volume of these voices significantly, the 2024 EP election delivered a clear message of a strengthened position of populist political parties in Czechia.

This research was supported by the NPO ‘Systemic Risk Institute’ project number LX22NPO5101, funded by the European Union–Next Generation EU (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, NPO: EXCELES).

(*) Vlastimil Havlík is associate professor at Masaryk University and the National Institute for Research on Socioeconomic Impacts of Diseases and Systemic Risks (SYRI) (https://www.syri.institute/). His research focus includes populism and political parties in Central and Eastern Europe. He is also editor-in-chief of the Czech Journal of Political Science (czechpolsci.eu). [ORCID: 0000-0003-3650-5783]

(**) Alena Kluknavská is assistant professor at Masaryk University and the National Institute for Research on Socioeconomic Impacts of Diseases and Systemic Risks (SYRI) (https://www.syri.institute/). Her research focuses on political communication and public and political discourses on migration and minority issues. She is also interested in understanding the communication strategies and successes of the populist radical-right parties and movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Recently, her work has focused on truth contestation and polarization in political discourse, particularly on social media. [ORCID: 0000-0002-3679-3335]

References

ANO (2024). Program hnutí ANO do voleb do Evropského parlamentu, https://www.anobudelip.cz/cs/eurovolby/nas-program/

Bernard, J., & Šimon, M. (2017). Vnitřní periferie v Česku: Multidimenzionalita sociálního vyloučení ve venkovských oblastech. Czech Sociological Review, 53(1).

Charvát, J., & Maškarinec, P. (2020). Volby do Evropského parlamentu v Česku v roce 2019: stále ještě druhořadé volby?. Centrum pro studium demokracie a kultury.

Czech Statistical Office. (2024). Election results. Retrieved 22 July 2024, from https://www.volby.cz/ De Lange, S. L. (2007). A New Winning Formula?: The Programmatic Appeal of the Radical Right. Party Politics, 13(4), 411–435.

Dvořák, Tomáš, and Jan Zouhar. (2022). Peripheralization processes as a contextual source of populist vote choices: Evidence from the Czech Republic and Eastern Germany. East European Politics and Societiesi, 37(3), 983–1010. https://doi.org/10.1177/08883254221131590

Dvořák, T., Zouhar, J., & Treib, O. (2024). Regional peripheralization as contextual source of populist attitudes in Germany and Czech Republic. Political Studies, 72(1), 112–133.

Grim, J. (2024). Kde uspěli Turek a Konečná? ‚Noví populisté‘ mobilizovali v krajských zákoutích a u lidí se základním vzděláním, Český rozhlas. https://www.irozhlas.cz/zpravy-domov/novi-populiste-turek-a-konecna-bodovali-na-hranicich-kraju-a-u-lidi-se-zakladnim_2406110500_jgr

Havlík, V. (2015). The Economic Crisis in the Shadow of Political Crisis: The Rise of Party Populism in the Czech Republic. In Kriesi, H. & Pappas, T. S. (Eds.), European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession. ECPR Press: 199–216.

Havlík, V., & Kluknavská, A. (2022). The Populist Vs Anti‐Populist Divide in the Time of Pandemic: The 2021 Czech National Election and its Consequences for European Politics. Journal of Common Market Studies, 60(S1), 76–87.

Havlík, V., & Kluknavská, A. (2023). Our people first (again)! The impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on the populist Radical Right in the Czech Republic. In Ivaldi, G., & Zankina, E. (Eds.), The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. European Center for Populism Studies: 90–101.

Havlík, V., & Voda, P. (2018). Cleavages, protest or voting for hope? The rise of centrist populist parties in the Czech Republic. Swiss Political Science Review, 24(2), 161–186.

Hrbková, L., Voda, P., & Havlík, V. (2024). Politically motivated interpersonal biases: Polarizing effects of partisanship and immigration attitudes. Party Politics, 30(3), 450–464.

Lysek, J., Pánek, J., & Lebeda, T. (2021). Who are the voters and where are they? Using spatial statistics to analyse voting patterns in the parliamentary elections of the Czech Republic. Journal of Maps, 17(1), 33–38.

Mahdalová, K., Škop, M. (2024). Exkluzivní průzkum ukázal, proč Češi přišli volit v rekordním počtu, https://www.seznamzpravy.cz/clanek/volby-eurovolby-exkluzivni-pruzkum-ukazal-proc-cesi-prisli-volit-v-rekordnim-poctu-254454

Plešivčák, M. (2020). Are the Czech or Slovak regions ‘closer to Europe’? Pro-Europeanness from a subnational perspective. AUC GEOGRAPHICA, 55(2), 183–199.

Reif, K., & Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second‐order national elections–a conceptual framework for the analysis of European Election results. European Journal of Political Research, 8(1), 3–44.

SPD (2024). Hlavní programové teze pro volby do Evropského parlamentu 2024, https://www.spd.cz/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Program-pro-volby-do-EP-2024-1.pdf

STEM (2024). Volební tendence české veřejnosti dva týdny před volbami do Evropského parlamentu, https://www.stem.cz/volebni-tendence-ceske-verejnosti-dva-tydny-pred-volbami-do-evropskeho-parlamentu/