DOWNLOAD ARTICLE

Please cite as:

Yilmaz, Ihsan & Morieson, Nicholas. (2024). “The Rise of Authoritarian Civilizational Populism in Turkey, India, Russia and China.” Populism & Politics (P&P). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). April 14, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0033

Abstract

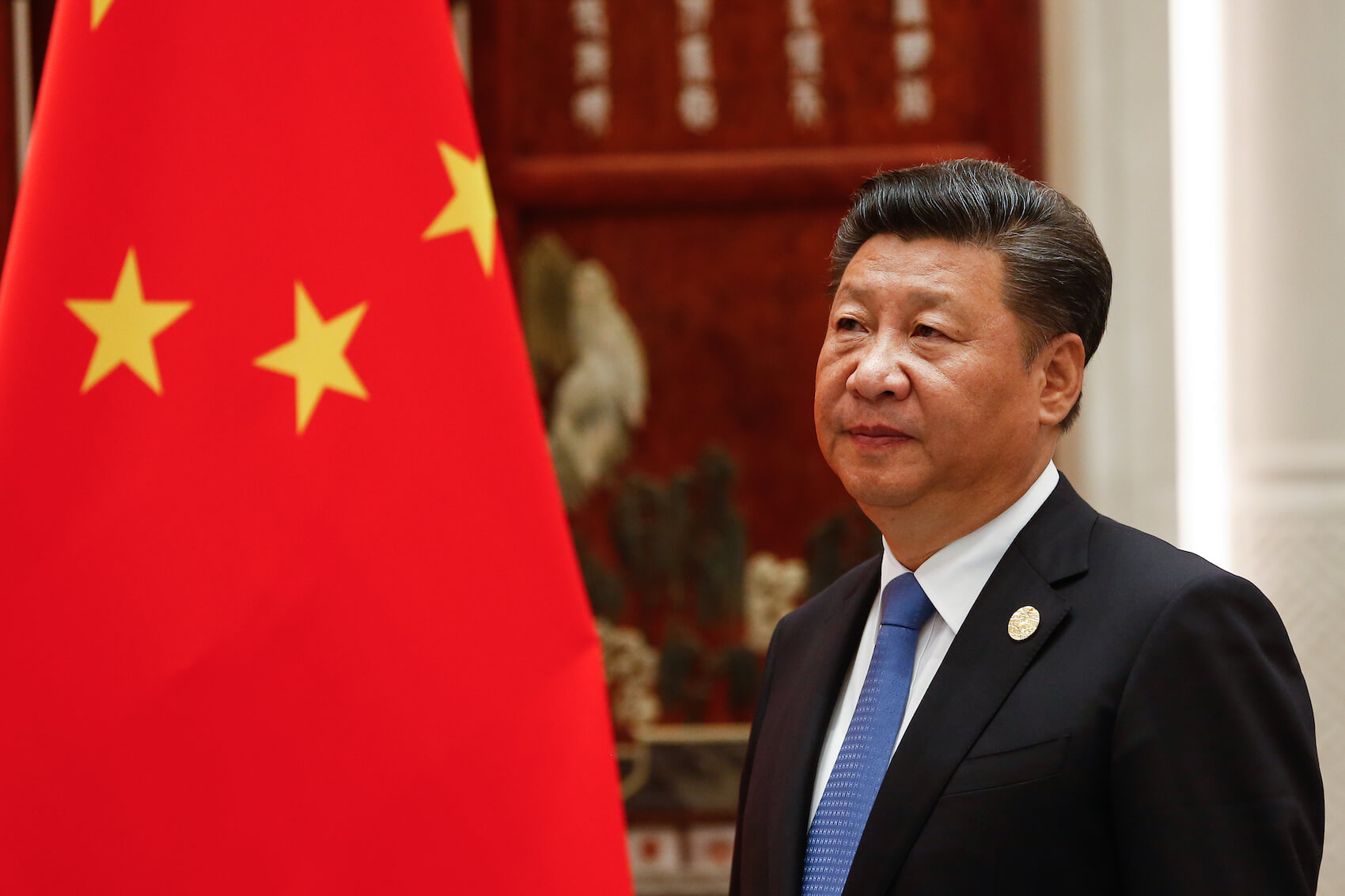

This paper comparatively analyses the phenomenon of civilizationalism within the discourse of authoritarian populism in four distinct political contexts: Turkey under Recep Tayyip Erdogan, India under Narendra Modi, China under Xi Jinping, and Russia under Vladimir Putin. We find that “authoritarian civilizational populism” has become a prominent feature in the discourses of leaders and ruling parties across China, Russia, India, and Turkey, serving as a multifunctional tool to construct national identity, delegitimize domestic opposition, and challenge Western hegemony. Across these nations, ‘the West’ is uniformly depicted as a civilizational ‘other’ that subaltern peoples must overcome to rejuvenate their respective civilizations. Also, civilizationalist discourses serve as a legitimizing tool for domestic authoritarianism and aggressive foreign policies. We also find while religion plays a central role in distinguishing ‘the people’ from ‘others’ in India and Turkey, and in grounding the cultural identity of ethnic Russians in Russia, China’s officially atheistic state utilizes a more syncretistic approach, emphasizing traditional beliefs while marginalizing ‘foreign’ religions perceived as threats to the Communist Party’s ideology.

By Ihsan Yilmaz & Nicholas Morieson

Introduction

The 21st century witnesses the rise of authoritarian regimes that claim to speak, not merely for citizens of their own nations, but for a broader transnational ‘people’ bound together through the common bonds of civilization. In Russia – where elections are held but opposition candidates regularly prevented from running and, in some cases, imprisoned and murdered – Vladimir Putin portrays his nation as a multi-cultural empire and a civilization deeply at odds with the liberal West. Putin himself claims to uniquely interpret the will of the Russian people, and to be their champion in a dangerous world dominated by the United States, a nation he claims that desires nothing more than the erasure of Russia’s traditional Christian values.

In China, since coming to power in 2013, Xi Jinping has portrayed himself as a simple man of the people fighting the corruption of Communist Party ‘princelings’ and ‘tigers,’ and moreover as a fatherly figure dedicated to protecting the Chinese people from both internal and external threats. Key to understanding China under Xi’s rule is his claim to be rejuvenating the great Chinese nation (or alternatively ‘race’), a nation that, according to Xi, incorporates so-called overseas Chinese and excludes some Chinese citizens, particularly Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang province.

In semi-democratic yet increasingly authoritarian Turkey and India, ruling populist leaders claim that their respective nations are contemporary manifestations of great religion-defined civilizations, and that the key to making their nations great is to return to the principles and values that made their respective civilizations powerful. At the same time, populist leaders portray certain religious and ethnic minorities as obstacles on the road to national and civilizational rejuvenation.

There is thus an intrinsic link between populism and civilizationalism in the respective discourses of ruling populists in China, India, Russia, and Turkey, insofar as the leader claims to represent the will of the people and therefore be above petty checks and balances on their power and democratic norms such as observing term limits, and further claim that ‘the people’ are not merely contained within the nation, but incorporate all peoples who belong to Chinese, Hindu, Russian (Christian Orthodox), and Ottoman (Islamic) civilization respectively.

In this article, then, we examine civilizationalism in authoritarian populism in four polities: Turkey and India, where authoritarian populism is emerging, and China and Russia, which have long been authoritarian but more recently turned toward populism under Xi and Putin respectively.

Populism and Authoritarianism

We may not ordinarily think of populism as a phenomenon occurring in non-democratic societies, or itself a non-democratic or at least non-electoral democratic phenomenon. However, since scholars began to identify political parties, movements, and leaders as ‘populist,’ authoritarian leaders and regimes have been identified as ‘populist.’ For example, Isaiah Berlin (1967: 14), reflecting on what he heard from other scholars, at the famous 1967 LSE populism conference admits that there exists a form of populism that “believes in using elites for the purpose of a non-elitist society,” and a type of populist “who has a ferocious contempt for his clients, the kind of doctor who has profound contempt for the character of the patient whom he is going to cure by violent means which the patient will certainly resist, but which will have to be applied to him in some very coercive fashion,” and who is in this way “on the whole ideologically nearer to an elitist, Fascist, Communist etc. ideology than he is to what might be called the central core of populism.”

Authoritarian populism was later discussed by Dix (1985), who found it in Latin American parties such as the National Popular Alliance in Columbia, and in Peronism in Argentina. Dix argued that it was possible to discern ‘democratic populism’ from ‘authoritarian populism.’ Authoritarian populism was led by military and/or the upper classes, drew support not from intellectuals or organized labour, but rather from the great mass of people. Moreover, it “mildly anti-imperialist” and was dependent on a single leader and the “leader’s myth.” Democratic populism was supported by intellectuals and organized labour, had less of a need for a single god-like leader, and possessed a strong ideology that was “well-articulated” (Dix, 1985: 47).

The concept of authoritarian populism fell largely into disuse outside of Latin America in the 1990s and 2000s. However, the concept has re-emerged and is today used to refer to “political phenomena in hybrid regimes and emerging democracies that share the core tenets of populism (namely, the construction of “the people”) while describing idiosyncratic trajectories distinct from that of populism in fully realized Western democracies (Guan & Yang, 2021). Mamonova (2019: 562), for example, argues that authoritarian populism combines “a coercive, disciplinary state, a rhetoric of national interests, populist unity between ‘the people’ and an authoritarian leader, nostalgia for ‘past glories’ and confrontations with ‘others’ at home and/or abroad.”

Other scholars, although observing key differences between populisms argue that all populisms are “susceptible to authoritarian tendencies over time,” a problem that “becomes apparent and radical when a populist movement takes state power and must navigate groups of influence among classes and balance the two basic and often contradictory state functions of capital accumulation and political legitimacy (McKay & Colque, 2021). Be this as it may, it remains possible to differentiate between democratic populism and authoritarian populism, and the latter is now an increasingly important concept in political science. For example, Guan and Yang (2021) observe that both Mamonova (2019) and Oliker (2017) “utilized the core definitions of authoritarian populism to deconstruct the popular support of the current Putin regime; namely, a powerful state, authoritarian leadership, nostalgia for past glories, and a rhetoric of “us versus them.” The Communist Party of China, led by the increasingly powerfull Xi Jinping, has also been described as ‘authoritarian populist’ (Tang, 2016), and indeed populism has a long history in China, rooted in Maoism if not in earlier rebellions of ‘the people’ against elites.

Based on Mamonova’s (2019) definition of authoritarian populism, and bearing in mind the tendency of populists to turn authoritarian once in power, it is possible to surmise that once democratic India and Turkey are in the process of turning toward authoritarian populism – a process that might be reversed – and that China and Russia are led by authoritarian populist regimes.

However, we argue that something else important unites these populisms in Turkey, India, China, and Russia: civilizationalism, or the belief that there are multiple world civilizations with incompatible values, and which often clash with one another (Yilmaz & Morieson, 2023a; Yilmaz & Morieson 2023b). We have previously defined civilizational populism as a group of ideas that together considers that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people, and society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’ who collaborate with the dangerous others belonging to other civilizations that are hostile and present a clear and present danger to the civilization and way of life of the pure people” (Yilmaz & Morieson, 2022: 19; 2023a: 5), a definition we apply here.

Civilizationalism is a component, though one not always recognized, of the authoritarian populisms of India, Turkey, Russia, and China. This is not merely because Russia and China, in particular, have sometimes been described as ‘civilization states,’ and at times wish to be perceived in this manner (Bajpai, 2024; Blackburn, 2021; Therborn, 2021; Acharya, 2020). Rather, it is because the type of authoritarian populism practised in each respective polity draws on nostalgia for a ‘golden age’ of ‘our’ civilization, and on claims that to become great again ‘our’ nation must return to the values of this golden age, to justify itself and because they each apply a civilizational categorization of peoples in order to determine ingroup from outgroup, and ‘the people’ from the ‘elite,’ or the betrayers of ‘our’ civilization.

Turkey

Perhaps the most studied example of civilizationalism in authoritarian populism is the President Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey (Yilmaz, 2021; Yilmaz & Morieson, 2023c; Uzer, 2020; Hazir, 2022). The AKP – under the guise of liberating ‘the people’ from elite misrule – set about dismantling Kemalist control over institutions such as the judiciary, bureaucracy and military, and following this installed their own supporters and allies within them. Çınar (2018) makes an interesting observation, noting that even in the first decade of its rule, the AKP possessed a civilizational perspective on international relations, and framed “Turkey’s integration with the EU in terms of a ‘reconciliation of civilizations’” (see also Bashirov & Yilmaz, 2020). In this way, the AKP “had from the very beginning identified Turkey with an unnamed non-Western civilization, but without explicitly rejecting the liberal political norms of European democracy” (Çınar, 2018).

A turning point came in 2013 when Erdogan began to lose popular support and AKP rule was challenged by mass protests. “When young people began to protest against a development planned for Gezi Park in Istanbul,” Erdogan “crushed the protests with violent force and demonized the protestors as anti-Muslim” and working with Western interests to subjugate Turkey (Yilmaz & Morieson, 2023a). And even greater turning point came in 2016 when a mysterious military coup attempt, plotted (according to the AKP and its allies) by the Gulen Movement – an ally (2002-2012) of Erdogan turned opponent – failed to remove Erdogan from power (Tas, 2018). In response, AKP officials claimed that the movement was not the sole mastermind behind the coup, but that the United States and broader Western world was ultimately responsible (Kotsev & Dyer, 2016).

Then, the AKP has increasingly implemented a strategy described by Yilmaz and Bashirov (2018: 1812) as “electoral authoritarianism as the electoral system, neopatrimonialism as the economic system, populism as the political strategy, and Islamism as the political ideology” (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018: 1812). This strategy also portrayed Turkey as “the legitimate inheritor of Ottoman legacies and power, the leader of the Islamic world, and the protector of Palestine” (Hintz, 2018: 37, 113). As his government pivoted toward Islamism, Erdogan began to present himself as the leader of all Muslims globally in their fight against the West, and in this way transnationalized and externalized his populism, making ‘the West’ the ultimate ‘elite’ and all Sunni Muslims the downtrodden ‘people’ requiring a champion to defend their interests (Yilmaz & Demir, 2023). As part of this strategy, the AKP attempts to construct a new ‘desired citizen,’ termed “Homo Erdoganistus” by Yilmaz (2021: 165), and described by him as “a practicing Sunni Muslim, believes in absolute authority, sees the Ottoman rule as the greatest era, believes their social purpose is to spread Islam in the public sphere, to provide aid to and deepen ties with Muslim and former Ottoman peoples and to regain Ottoman glory” (Yilmaz, 2021: 165).

Erdogan’s civilizational restoration efforts resulted in the politicizing of Turkish foreign policy by constructing foreign threats (Taş, 2022a; 2022b). Turkey’s foreign policy efforts are justified on the basis that Turkey is heir to the Ottoman legacy and thus the leader of the ummah, and therefore ought to act to ‘defend’ Muslims across the Middle East and North Africa (Dogan, 2020; Özkan, 2015).

The AKP’s foreign and domestic policies thus reflect its civilizational populism. Erdogan and his party justify growing authoritarianism through claims that their marginalization of rivals and religious minorities as necessary to ‘protect’ the ummah from Western threats to Turkey and Islam, and as part of a civilization restoration project that promises to rejuvenate Ottoman civilization. Equally, they legitimize their bellicosity and imperialism abroad through claims that Erdogan is the leader of the global ‘ummah’ and Turkey heir to the Ottoman Empire and thus responsible for protecting the global ummah from Western aggression.

India

Following their election victory in 2014, India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has set about transforming India, de-secularizing and Hinduizing the nation, removing checks and balances on government power, replacing the old secular Congress Party-aligned ‘elite’ from the bureaucracy with BJP supporters and allies, and reaching out to Hindus globally to create closer ties between them and India’s government and people. The result is a less democratic, less plural, and more authoritarian and aggressively ‘Hindu’ India.

BJP’s ideology, Hindutva, proposes that India belongs to the Hindu people, who are defined in ethnic and cultural terms rather than as followers of a particular religious code. Hindutva defines “Indianness exclusively in religious terms: an Indian is someone who considers India as their holy land” (Ahmad, 2007).

Leidig (2020) argues that “Hindutva was not truly ‘mainstreamed’ until the [2014] election victory of the BJP and current prime minister Narendra Modi. Modi’s populism and ability to create a mass movement are based on exploiting ressentiment and anger toward the Hindu people’s historical oppressors (Muslims, the British) and promising to revive and rejuvenate Hindu civilization (McDonnell & Cabrera, 2019). Modi styled himself as a man of the people, the son of a chai wallah, and a pious Hindu. Moreover, Modi won power by promising to end the allegedly corrupt role of the secular Congress Party, to fast-track India’s economic development, and to govern in the interest of ‘the people’ (Saleem, 2021; McDonnell & Cabrera, 2019). Modi’s conception of ‘the people’ did not include certain non-Hindu groups, including Muslims – 200 millions of whom live in India. Indeed, the party regards Muslims and secularists, in particular, as threats to their civilizational rejuvenation project (Saleem, 2021; McDonnell & Cabrera, 2019; Tepe & Chekirova, 2022).

Perceived as a threat to Hindu cultural hegemony on the basis that they belong to a foreign civilization that once dominated the Hindu majority, the BJP and their allies in the Hindutva movement encourage Hindus to fear and despise Muslims, demonizing them through accusations that they are waging “Jihad” against Hindus, including a ‘love Jihad’ in which Muslim men supposedly marry Hindu women to forcefully convert them to Islam, and for “spreading the coronavirus, for buying land, for selling vegetables (“Corona Jihad,” “Land Jihad,” “Vegetable Seller Jihad”) (Kaul, 2023). Secularists, too, have suffered under the BJP’s authoritarian populism, particularly perceived members of the old ‘elite’ (Ellis-Petersen, 2023).

The BJP conflates “westernized Indian elites and foreign others” (Hulu, 2022), who together pose a “collaborative threat to ‘the people’” and stand in the way of ‘the realization of a strong and monolithic Hindu identity” (Wojczewski, 2019; Plagemann & Destradi, 2019). The belief that Western ideas should be purged from India led the BJP to “saffronize” the foreign service, a process in which India’s political institutions are refashioned “to reflect [Hindu] majoritarian ideals” and civilizationalism, forcing ‘elite’ diplomats to either abandoned their attachments to ‘foreign’ ideas such as secularism and pluralism and conform to Hindutva ideals or leave the service (Huju, 2022: 423).

Journalists who dare to criticize Modi’s government have also been attacked by the BJP. The party has increasingly sought to intimidate domestic and international media operating in India, including the BBC, which the BJP accused of having a “colonial mindset” (The Guardian, 2023). Thus, journalists are portrayed as a part of a cultural ‘elite,’ or in the case of Muslim journalists as a dangerous ‘other’ that is either opposed to Hindu nationalism or insufficiently supportive of Modi’s civilization restoration project and are therefore subjected to campaigns of abuse intended to silence them. These acts are legitimized – as in many other cases – by the BJP’s Hindu Nationalist ideology, and the party’s claims that Muslims and secularists are preventing the nation from restoring itself to its former glory.

The BJP’s civilizational populism thus helps the party to frame its opponents as belonging to threatening foreign civilizations – whether Islam or the neo-colonial West, or even China – and to portray Modi as a protective and powerful leader who will stand up for the interests of Hindu ethnic Indians globally and within India.

Russia

Since 2012, the Putin regime in Russia has increasingly sought to identify the nation as a civilization-state (Blackburn, 2021; Marten, 2014; Teper, 2015). Putin portrays Russia as a state that is also heir to two multi-ethnic, multi-religious empires (i.e. the Russian Empire and Soviet Union) that accommodated minorities. Moreover, he portrays Russia as a civilization distinct from the Western civilization, yet not wholly Eastern. Putin’s imagined Russia is multicultural, but not liberal, conservative in its values, respectful of all religions and cultures within its boundaries, but faces implacable hostility from the liberal West. The liberal West is Russia’s key enemy, especially insofar as it is bent on pushing liberal values onto Russia and invading its sphere of influence, for example by expanding NATO to incorporate former Soviet territories and previously neutral nations.

Although there is debate over whether Putin ought to be called a populist, even critics of labelling Putin a populist admit that he at times performs as a populist. For example, March (2023), who considers it misleading to call Putin a populist, admits that the Russian President uses populist rhetoric when he wishes to present himself – most often disingenuously – as a ‘man of the people’ fighting corrupt elites, and in order to draw support from different elements within Russian society who share little but a common resentment towards the oligarchs (March, 2023). Putin also portrayed himself – like other populists – as the savior of the nation and its people, and as a powerful, masculine leader who would restore Russia’s prestige following the collapse of the Soviet Union (Eksi & Wood, 2019).

As Western liberal democracy became increasingly cited by Putin as the enemy of the Russian people and their traditional Orthodox Christian culture, so too did the notion that Russia was separate from the West – and perhaps its own particular civilization – become an important element in Putin’s populist discourse. Once Putin had established himself in power and destroyed the influence of his oligarchic enemies (he permitted, of course, the existence of tamed oligarchs who supported his rule), he leaned heavily on a new populist discourse: dividing society between authentic Russians and the pro-Western liberals who sought to undermine traditional culture and impose Western culture on the Russian people. In a related development, Blackburn (2021) observes a turn in Putin discourse in 2012, after which the Russian president became enamored with the notion of Russia as a ‘civilization state’ distinct from the West, and that possesses certain values that are inherently at odds with Western liberal values (Novitskaya, 2017; Edenborg, 2019). As a result, “Russian foreign policy was recalibrated” to portray Russia not as “a potential partner of the West,” as it had been previously, but as “an independent, revisionist Eurasian power” (Blackburn, 2021; Newton, 2010; Trenin, 2015). Moreover, “concepts of civilizations in competition and multipolarity were soon promoted to explain this new direction” (Blackburn, 2021; Verkhovsky & Pain 2012; Pain, 2016; Laruelle, 2017; Ponarin & Komin, 2018).

Putin’s ‘state-civilization’ thus encourages Russians to feel a kinship with one another “without forced Russification or reduction of ethnic and cultural diversity” (Blackburn, 2021) and loyalty toward the state and Putin, and to perceive this unity and loyalty as part of Russia’s traditional values and indeed part of its imperial and Soviet History (despite many examples to the contrary, and in which minorities were persecuted). The ’state-civilization’ discourse is useful for Putin and is easily incorporated into his wider populist discourse. Putin’s rhetoric on the Russia-Ukraine war provides a demonstration of Putin’s populist use of the state-civilization discourse. In 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Shortly before the war, Putin claimed that Ukraine was part of Russia, and that Ukrainians and Russians were “one people” with “spiritual” and “civilizational ties” (Putin, 2021). Explaining this assertion, Putin (2021) looked back at the history of Slavic peoples and claimed that “Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians are all descendants of Ancient Rus, which was the largest state in Europe. Slavic and other tribes across the vast territory – from Ladoga, Novgorod, and Pskov to Kiev and Chernigov – were bound together by one language (which we now refer to as Old Russian), economic ties, the rule of the princes of the Rurik Dynasty, and – after the baptism of Rus – the Orthodox faith. …The Tale of Bygone Years captured for posterity the words of Oleg the Prophet about Kiev, ‘Let it be the mother of all Russian cities.’”

In 2023, Putin gave a speech to the Valdai discussion club specifically on the concept of civilization and took questions from the audience on the topic. It is very revealing of Putin’s thoughts on the matter, and why he believes civilization-states will determine the political future of the globe (Putin, 2023). According to Putin, “relying on your civilization is a necessary condition for success in the modern world” insofar as “humanity is not moving towards fragmentation into rivalling segments, a new confrontation of blocs, whatever their motives, or a soulless universalism of a new globalization. On the contrary, the world is on its way to a synergy of civilization-states, large spaces, communities identifying as such” (Putin, 2023). Rejecting any notion of universal values, Putin claimed that “civilization is not a universal construct, one for all – there is no such thing. Each civilization is different, each is culturally self-sufficient, drawing on its own history and traditions for ideological principles and values” (Putin, 2023).

Putin portrays himself as a defender of Russian civilization and the Russian people. At the same time, he portrays the West as the manipular of Ukrainian elites, and an increasingly godless and decadent society that not only turned its back on its traditional Christian values but refuses to respect other civilizations. Portraying ‘the people’ as ‘pure’ is a part of populism, and Putin’s populism is no different to other populisms in this respect, even as its focus on portraying Russia as a multi-ethnic, multi-religious civilization respectful of other civilizations and of the diverse peoples within its borders – with the ethnic Russian Orthodox Christian people as its core, defining group – and lack of anti-immigration rhetoric sets it apart from similar right-wing populisms in Europe and North America.

China

Scholars have observed how Chinese conceptions of democracy have often been essentially populist, insofar as if the government is perceived to serve the will or interests of the people it is classed as democratic, regardless of whether elections are held. Populist understandings of democracy are so ingrained in Chinese, some scholars argue, that even the pro-democracy campaigners of the 1980s conceived of democracy largely in a populist manner and were less interested in holding elections than in forcing the government to serve the authentic interests of the people. Scholars have also identified two key forms of populism operating in China. Both incorporate nationalism (Li, 2021; Miao, 2020; Guo, 2018, Eaton & Müller, 2024) and grievances related to China’s growing economic inequality (Eaton & Müller, 2024; Li, 2021; Miao, 2020; Guan & Yang, 2021). However, according to Guan and Yang (2021) a key difference between populisms in China lies in their relationship to the government. One type of populism, they argue (Guan & Yang, 2021) is essentially top-down and “pro-system” and presents the CCP as the people’s champion and defender against their enemies, while another is “anti-system,” largely online, and is the product of anger toward the CCP’s due to the party’s corruption and the economic inequality its permits to increase.

Eaton and Müller (2024) point out that other scholars have also come to a similar conclusion that multiple populisms operate in China, including He & Broersma (2021: 3015) who argue that a form of ‘classical communist populism’ …coexists with an online “bottom-up populism” which ‘highlights antagonism between the people and corrupt elites’.” Undoubtedly, the most pervasive and important form of populism in China is the top-down, pro-system form associated with Xi Jinping, who presents himself as a man of the people fighting a corrupt elite within the party, but also as a loyal Communist Party member fighting on behalf of the entire Chinese people – globally – and against American hegemony.

Populism is not new to China. Indeed, some scholars refer to Communist China as a society dominated by “populist authoritarianism” (Tang, 2016). Under Mao’s long rule (1949-1976) populist conceptions of democracy were employed alongside a cult of personality centered on Mao, which presented him as the Great Helmsman (Chinese: 伟大的舵手; pinyin: Wěidà de duòshǒu) who had the unique ability to unite the Chinese people and govern them accordance with their interests. Mao’s political legitimacy was thus not conferred on him via elections, but rather through his ability to know the will of the people and fight for their interests against the Chinese ‘elite’ (e.g. landowners, businesspeople, Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) leaders and supporters, educated people in cities). Mao, of course, was following an authoritarian populist model set by Lenin and Stalin in the Soviet Union, who similarly argued that legitimacy was conferred upon their regimes not through elections but insofar as they represented the interests of ‘the people,’ (e.g. the proletariat, intellectuals who supported the revolution) and sought to eliminate or re-educate their ‘elite’ enemies (i.e. White Russians, landowners, the merchant class, Kulaks, business people). These authoritarian populists sought to discipline their societies and educate ‘the people’ to become good citizens in a workers’ state, often using violent coercion to achieve these goals. Mao’s acts of coercion during the Great Leap Forward and the chaotic violence he unleashed during the Cultural Revolution – a form of top-down populist mobilization – are extreme examples of the violence he encouraged in order to ‘complete’ his revolution.

Mao described the ‘new’ form of democracy he was creating in China as a “people’s democratic dictatorship.” Mao’s concept is inherently populist, insofar as in his people’s democratic dictatorship the people live in a democracy (i.e. the government does the will of the people), but the ‘others’ live in a dictatorship in which they are subject to violence and extreme forms of discipline unless they accept the dictatorship of the people. Of course, the people in Mao’s China did not directly rule. Rather, as in the Soviet Union, the Communist Party substituted itself for ‘the people’ and then a single leader – Mao – substituted himself for the Communist Party, essentially ruling as a dictator although always in the name of the people.

Following Mao’s death and a brief leadership struggle, Deng Xiaoping emerged as paramount leader and – among his many economic and political reforms – sought to ensure that no future party leader could establish a personality cult and rule with arbitrary power, that the educated and merchant class ‘elites’ repressed by Mao would now be encouraged to become entrepreneurs in the new capitalist China, and that a kind of deliberate democracy might exist within the Communist Party in order to prevent leaders from making foolish decisions. Deng might be understood as attempting to turn China away from authoritarian populism and towards a kind of authoritarian, meritocratic, and development focused technocracy ruled by a ‘wise’ elite in which – to use his famous dictum – it didn’t matter whether a cat was black or white, only whether it could catch mice. However, Tang (2016) argues that the CCP has remained as a “populist authoritarian” party due to its Mao era concept of the “mass line” (群众路线), an organizational and ideological principle that insists that the CCP must listen to ‘the people,’ pool their wisdom, and formulate theories and then policies based on their demands (Lin, 2006: 142, 144, 147). The ‘mass line’ insists to the party leaders that the people, although inarticulate, have innate wisdom that must be listened to and to which the party must attend, an idea which Shils (1956: 101) identified in populist discourses when he observed that populism was “tinged” with the idea that in certain respects the people were superior to their rulers.

Although in the Deng era the ‘mass line’ ideology was de-emphasized, under Xi Jinping’s leadership the concept has returned to prominence, and the CCP has arguably returned to authoritarian populist rule. Indeed, while Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao conformed largely to the rules set in place by Deng and governed as authoritarian technocrats, Xi Jinping has in certain respects re-oriented China towards authoritarian populism while increasing emphasis on the civilizational identity of the Chinese ‘people’ and their opponents. Under Xi’s rule, according to Guan and Yang (2021: 463), the ‘mass line’ has grown in importance, and now serves a discourse that “glorifies the contribution of ordinary people to modern Chinese history in order to create a unified ‘great Chinese identity’.”

The return of the mass line is part of a wider return to authoritarian populism under the rule of Xi Jinping since 2013. Following an internal election which saw him become CCP General Secretary and national leader in 2013, Xi declared the importance of the ‘mass line’ and his intention to listen to ‘the people’ and represent their interests. Xi presented himself as a man of the people from humble beginnings (despite his own father being a high-ranking CCP official, albeit one who fell afoul of the regime and was sent down to the countryside to live as a peasant) and who would fight against ‘elites’ within the CCP in order to protect the people.

For example, as national leader, Xi demanded the “purification” of the CCP, often interpreted as an attack on the extravagance of the hedonistic and corrupt party ‘elite.’ Xi himself called for party members to live more Spartan lifestyles, and punished thousands party officials who were seen to be wasting public money or acting corruptly and illegally. In this way, Xi appeared to be sincerely fighting against their avarice of the ‘elite’ that had gained power during the post-Mao period and attempting to return the nation to the authoritarian populist ‘democracy’ it had been under Mao.

Xi increasingly gained power within the CCP by presenting himself as the people’s savior and his enemies within the party as ‘tigers’ such as Bo Xilai alleged to have illegitimately gained power and who did not serve the interests of ‘the people.’ Although it may appear that Xi was sincere in his attempts to end avarice and corruption, he appears to be corrupt himself, and he largely targeted opponents and rivals within the CCP, ignoring the corruption of his allies. Thus, populism was thus a useful means through which Xi could establish himself in power and destroy potential political rivals from within his own party.

A key element of Xi’s populism is the increased emphasis he places on restoring Chinese civilization and the Chinese (Han) people to their rightful place at the center of world affairs. Indeed, as we shall see, Xi’s civilizational narrative has a populist element insofar as he portrays himself and the CCP as rejuvenating the Chinese people via an agenda that stresses the long civilizational history of the Chinese people, the superiority of this tradition to the far newer civilization of the West, and amid claims that the West is waging a civilizational war on China by refusing to permit China’s peaceful rise to hegemon in Asia. In this narrative the Chinese people are the Han people globally and tolerated minorities within China’s borders, and the enemy ‘elites’ are largely external, and consist of the United States, the broader West, and Japan – or the global powers that support American hegemony and try to keep China from displacing the United States as global hegemon. The civilization narrative not only defines the character of the Chinese people and their global enemies, but it legitimizes Xi’s authoritarianism at home and his bellicosity abroad, insofar as he portrays himself as the democratic instrument of the will of the Chinese people, and his repression of domestic minority groups and aggression toward foreign nations as necessary for China’s civilizational rejuvenation and to defend the Chinese people from the hostile West and Japan.

The CCP has a complex relationship with China’s cultural heritage, and with what we might call ‘Chinese civilization.’ As historian C. P. Fitzgerald (1977) observed, although Mao transformed China by destroying not merely the capitalist republican regime and its nationalist (Kuomintang) government, but also by attempted to destroy the element of Chinese culture which he thought most pernicious: Confucianism. Thus Mao, according to Fitzgerald (1971: 483), was not aiming to destroy Chinese civilization and culture (wen hua) – elements of which he admired. At the same time, Mao encouraged archaeological excavations which he used to glorify Chinese civilization and show that Communists were not indifferent to art and beauty (Fitzgerald, 1971: 489) and “shared the opinion of the mass of Chinese that the long duration and continuity of Chinese civilization, proved by its magnificent and unbroken historical records, was a clear proof of superiority” (Fitzgerald, 1971: 490-491).

The revival and rehabilitation of Confucianism following Mao’s death and accelerating and transforming into a civilizational ethos under Xi, is perhaps a demonstration of the failure of Mao’s attacks on Confucianism, as is, perhaps, Samuel P. Huntington’s description of China belonging to “Confucian civilization” (Huntington, 1993). Deng Xiaoping and his successors, recognizing the failure of Maoism to develop China, turned the nation sharply away from Maoism and drew on Confucianism and its focus on social harmony, order and tradition in order to construct a new national ideology, which later became known as “Socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Where Mao though that Chinese civilization had fallen low due to the backward-looking nature of Confucianism, Deng saw positive things in Confucianism. Indeed, Prosekov (2018) describes – arguably in a somewhat exaggerated manner – contemporary China as “a socialist state in which Marxism-Leninism as an ideology is harmoniously combined with the traditional philosophical doctrine – Confucianism.” The ‘new’ Confucianism became part of the identity of the Chinese people, binding them to China’s grand history and, to a degree, also provided them with a moral system – something lacking in Maoism. Instead of marking a radical break, Deng’s and his successors’ adding of Confucianism into Chinese state ideology meant the Communist revolution became another development of Chinese civilization, one which would ensure China would again be a powerful state.

Under Xi, the term “has undergone both a promotion and a facelift” insofar as Xi stresses “the uniqueness of the Chinese civilization and the notion of proud nation framework-building” (Brown & Bērziņa-Čerenkova, 2018). The spiritual civilization Xi is building is uniquely Chinese. He dismisses Western values as non-universal and thus unsuitable for China (Brown & Bērziņa-Čerenkova, 2018). Thus, Xi’s concept of ‘spiritual civilization’ represents an attempt to contribute an indigenous Chinese alternative to Western liberal democracy and capitalism and mixes traditional culture (especially ideas drawn from Confucianism) “with Socialist ethos-in-transition, known as the Socialist core value outlook (shehui hexin jiazhiguan)” (Brown & Bērziņa-Čerenkova, 2018).

In a narrative that demonstrates Xi’s ability “to adopt traditional culture,” borrowing “the Confucian family-country parallel” and merging it into Chinese socialism, he claims that in order to construct this “spiritual civilization” the Chinese people, according to Xi, must have “faith” so that China may have “hope” and that this faith and hope will lead to the nation possessing great “power” (Brown & Bērziņa-Čerenkova, 2018). Global power can thus only “be achieved by constructing a spiritual civilization, spreading ‘excellent Chinese traditional culture’ (Zhongguo youxiu chuantong wenhua) and core Socialist values” (Brown & Bērziņa-Čerenkova, 2018).

This is just one example of a trend occurring under Xi’s leadership of the CCP, namely, the growing emphasis placed on the long history of Chinese civilization, the invocation of its “five thousand years of continuous civilization,” and the inherently civil and cultured (wenming) nature of its people in order to counter the notion that China is “backward and undeveloped” (Brown & Bērziņa-Čerenkova, 2018). The notion of five thousand unbroken years of history is useful for Xi insofar as it proves that Chinese civilization is superior to all others due to its longevity. It also legitimizes the CCP by portraying the party as leading Chinese people – and thus Chinese civilization – toward the zenith of its power and influence. Equally, by describing China as a civilization and not merely a nation-state, Xi is able to include all Han people globally within China. The Chinese diaspora has been very important post-Mao to China’s economic development. However, Xi also seeks to mobilize Han Chinese globally to intimidate China’s critics, to commit acts of espionage, and to influence foreign governments.

China’s development and increasing international influence – and at times bellicosity – is framed in civilizational terms by Xi, and as ‘the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people’ (i.e. the Han people). However, Xi Jinping does not discuss at length, as in the manner of Putin, the nature of civilizations and the exact nature of Chinese civilization. Rather, he discusses the importance of “harmony” between civilizations and criticizes the West for not respecting civilizational differences and behaving in an antagonistic manner toward China (Xinhua, 2021). Moreover, Xi warns that conflict will ensue if the United States and its allies (i.e., the West and Japan) intervene should China invade Taiwan, and he encourages the Chinese people to resist “foreign, imperialist influence.” Xi, thus, tells the Chinese people that they are in a civilizational conflict with the West in which China is the rising power determined to break free of constraints and take back a central role of global affairs and reunite the two Chinas (i.e. the PRC and Taiwan) and the West – particularly the United States – is attempting to prevent China’s rise to regional if not global hegemon.

Like Putin, Xi does not consider China only the property of a single ethnic group. China’s occupation of Tibet was justified on the basis that the region was part of historical Chinese civilization, and that therefore by invading the territory China was liberating Tibetans (Sen, 1951: 112). If Tibetans do not wish to be part of China, the CCP perceives their acts of rebellion as illegitimate insofar as their lands are an intrinsic part of China. Ethnic minorities that seek independence are punished by the CCP, which moves large numbers of Han Chinese into those regions in an attempt to make the inhabitants a minority and the Han the majority, and in the case of Xinjiang province, through large-scale so-called re-education campaigns sometimes involving concentration camps.

Conclusion

The notion that the world can be divided into several distinct civilizations, and that these civilizations often clash with each other due to possessing opposing values, is present in the discourses of authoritarian populists in non-democratic China and Russia, as well as in competitive authoritarian India and Turkey. Civilizationalism is, therefore, a key element in state discourses in the two largest nations on earth (China and India), in major power Russia, and regional power Turkey, where it plays several important roles.

First, civilizationalism helps authoritarian populists to construct a ‘people’ and their ‘elite’ enemies, as well as ‘dangerous others.’ We find that religion plays an important but not always decisive role in civilizational populist identity making. In Turkey and India, religion plays the key role in distinguishing ‘the people’ from ‘others,’ but also from the domestic secular ‘elites’ who abandoned the authentic religion of their civilization and allied themselves with foreigners, and thus betrayed ‘the people.’ Although Putin claims that Russian is a multi-religious civilization, Russian Orthodoxy is a key element in the cultural identification of ‘the core people of Russian civilization,’ the ethnic Russians. In China, where the state is officially atheist, the typically syncretistic beliefs of the Chinese people are tolerated insofar as they are considered traditional and indigenous to China, Confucianism (not a religion per se, but an ideology that condones Daoist and Chinese folk religion, religious worship) is encouraged, and ‘foreign’ religions Islam and Christianity, along with religious movements perceived to be hostile toward the CCP and/or communism, marginalized and sometimes outlawed.

In all cases ‘the West’ is considered a civilizational ‘other’ and it is only in India where the domestic Muslim population is the ultimate ‘other’ rather than the West. The West represents, in the international sphere, the ‘elite’ power that the subaltern peoples must overcome in order to return their respective civilizations to greatness. Thus, we witness the formation of a loose alliance among non-liberal, predominantly non-Western regimes. They assert that supposed ‘universal values’ are actually specific Western values, arguing that concepts such as liberalism and cosmopolitanism are ill-suited for non-Western societies. They contend that the adoption of these values by non-Western societies inhibits the revitalization of non-Western civilizations. Consequently, we observe Erdogan advocating for a ‘war of liberation’ against the dominant West, while China and Russia seek to challenge Western liberal hegemony wherever possible. Indeed, leaders such as Putin, Xi, Modi, and Erdogan aspire to liberate their societies from ‘universal values’ and to revive the values that historically empowered their respective civilizations.

Second, civilizational populist discourses are used by authoritarian leaders to legitimize authoritarianism at home and bellicosity abroad. In Modi’s India, the repression of Muslims is framed as necessary to protect Hindu cultural and political hegemony, and the removing of the old secular elite is framed as decolonization, and thus the liberating of Hindus from Western imperialism, an act that allegedly leaves Hindus free to restore the greatness of Hindu civilization.

In Xi’s China, minorities and dissidents are ‘re-educated’ in brutal conditions, and neighboring countries are threatened with China’s military might, to defend Han-Chinese cultural hegemony and to rejuvenate Chinese civilization, including the recovery of territories supposedly possessed by China during its imperial period, and before the so-called century of humiliation. Non-Chinese religions are suppressed and depicted as foreign imperialist impositions on China or as non-indigenous and therefore inferior forms of state organization.

Putin’s repression of sexual minorities and his invasion of Ukraine are presented by the Russian leader as necessary acts to protect the Russian people from ‘the West’ and its corrosive liberal ideology. Erdogan portrays repression of dissidents, people associated with the Gulen Movement, and marginalization of non-Sunni Muslims, non-Muslims, and the old secular-nationalist (Kemalist) governing elite as necessary to protect Turkey from the foreign and domestic forces that wish to dismember the nation and to “liberate” the nation from Western ideologies and return it to the greatness of the Ottoman period by embracing Islamist nationalism.

Finally, of the four leaders discussed in this article, only Putin explicitly challenges the nation-state paradigm, while the others merely conflate state and civilization and remain nationalist. Moreover, only Putin speaks at length about the concept of civilization states, which he alone claims will dominate the future of global politics. Be this as it may, the fact that regimes in India, Russia, Turkey, and China, use authoritarian civilizational populist discourses – discourses that are inherently anti-Western and anti-liberal – tell important things about the shape global politics is likely to take in the future. The rise of authoritarian regimes using civilizational populist discourses suggests that the concept of universal values is likely to come under further pressure, as non-Western civilization states or nation states that also identify as heirs to particular civilizations, increasingly challenge Western hegemony and liberal democratic norms both domestically and in the international sphere. The close relationship between China and Russia suggests a joint front of two authoritarian and civilizational populist regimes against a shared enemy: The liberal democratic West.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian Research Council [ARC] under Discovery Grant [DP220100829], Religious Populism, Emotions and Political Mobilisation.

References

Acharya, Amitav. (2020). “The Myth of the ‘Civilization State’: Rising Powers and the Cultural Challenge to World Order.” Ethics & International Affairs. 34.2 (2020): 139–156. doi: 10.1017/S0892679420000192.

Ahmad, Irfan. (2017). “Modi’s Polarising Populism Makes a Fiction of a Secular, Democratic India.” The Conversation. July 12, 2017. https://theconversation.com/modis-polarising-populism-makes-a-fiction-of-a-secular-democratic-india-80605 (accessed on April 11, 2024).

Bashirov, Galib and Yilmaz, Ihsan. (2020). “The rise of transactionalism in international relations: evidence from Turkey’s relations with the European Union.” Australian Journal of International Affairs, 74(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2019.1693495

Berlin, Isaiah. (1957). “To Define Populism.” The Isaiah Berlin Virtual Library. https://berlin.wolf.ox.ac.uk/lists/bibliography/bib111bLSE.pdf

Blackburn, Matthew. (2021). “Mainstream Russian Nationalism and the ‘State-Civilization’ Identity: Perspectives from Below.” Nationalities Papers. 49(1): 89–107. doi: 10.1017/nps.2020.8

Brown, K.; Bērziņa-Čerenkova, U.A. (2018). “Ideology in the Era of Xi Jinping.” J OF CHIN POLIT SCI. 23, 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-018-9541-z

Çınar, Menderes. (2018). “From Moderation to De-moderation: Democratic Backsliding of the AKP in Turkey.” In: The Politics of Islamism. Middle East Today. Edited by J. Esposito, L. Zubaidah Rahim and N. Ghobadzadeh. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dix. Robert H. (1985). “Populism: Authoritarian and Democratic.” Latin American Research Review, 20(2), 29–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2503519

Dogan, Recep. (2020). “The Political Theology of Political Islamists of Turkey. In: Political Islamists in Turkey and the Gülen Movement.” Middle East Today. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29757-2_6

Edenborg, E. (2019). “Russia’s spectacle of ‘traditional values’: Rethinking the politics of visibility.” International Feminist Journal of Politics, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2018.1560227.

Eksi, Betul & Wood, Elizabeth A. (2019). “Right-wing populism as gendered performance: Janus-faced masculinity in the leadership of Vladimir Putin and Recep T. Erdogan.” Theory and Society, 48 (5):733-751. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45219741

Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. (2023). “Rahul Gandhi could face jail and loss of seat after Indian court rejects plea.” The Guardian. April 20, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/20/rahul-gandhi-facing-jail-and-loss-of-parliamentary-seat-after-indian-court-rejects-plea (accessed on April 13, 2024).

Fitzgerald, Charles Patrick. (1971). Communism Takes China: How the Revolution Went. Published by McGraw-Hill.

Fitzgerald, C. P. (1977). Mao Tse-tung and China. Harmondsworth, England ; New York : Penguin Books.

Guan, T. & Yang, Y. (2021). “Rights-oriented or responsibility-oriented? Two subtypes of populism in contemporary China.” International Political Science Review, 42(5), 672-689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120925555

Hazir, Umit Nazmi. (2022). “Anti-Westernism in Turkey’s Neo-Ottomanist Foreign Policy under Erdoğan.” Russia in Global Affairs, 20: 164–83. DOI: 10.31278/1810-6374-2022-20-2-164-183.

Hintz, Lisel. (2018). Identity Politics Inside Out: National Identity Contestation and Foreign Policy in Turkey. New York: Oxford University Press.

Huju, Kira. (2022). “Saffronizing diplomacy: the Indian Foreign Service under Hindu nationalist rule.” International Affairs. Volume 98, Issue 2, March 2022. Pages 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab220.

Huntington, S. P. (1993). “The clash of civilizations?” Foreign Affairs, 72(3), 22-49.

Kaul, Nitasha. (2023). “Increasing Authoritarianism in India under Narendra Modi.” Australian Institute of International Affairs. August 2, 2023. https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/increasing-authoritarianism-in-india-under-narendra-modi/ (accessed on April 11, 2024).

Kotsev, Victor & Dyer, John. (2016). “Turkey blames US for coup attempt.” USA Today. July 18, 2016. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2016/07/18/turkey-blames-us-coup-attempt/87260612/ (accessed on April 11, 2024).

Laruelle, Marlene. (2017). “Is Nationalism a Force for Change in Russia?” Daedalus. 146 (2): 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00437

Lin, Chun. (2006). The transformation of Chinese socialism. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. pp. 142, 144, 147.

Mamonova, Natalia. (2019) “Understanding the Silent Majority in Authoritarian Populism: What can we learn from popular support for Putin in rural Russia?” The Journal of Peasant Studies. 46(3): 561–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1561439

March, Luke. (2023). “Putin: populist, anti-populist, or pseudo-populist?” Journal of Political Ideologies. (2023): 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2023.2250744

Marten, Kimberly. (2014). “Vladimir Putin: Ethnic Russian Nationalist.” Washington Post, March 19. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/03/19/vladimir-putin-ethnic-russian-nationalist/.

McKay, B. M. & Colque, G. (2021). “Populism and Its Authoritarian Tendencies: The Politics of Division in Bolivia.” Latin American Perspectives, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X211052980

Newton, Julie. (2010). “Shortcut to Great Power: Russia in Pursuit of Multipolarity.” In: Institutions, Ideas and Leadership in Russian Politics, edited by Newton, Julie and Tompson, William, 88–115. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Novitskaya, Alexandra. (2017). “Patriotism, Sentiment, and Male Hysteria: Putin’s Masculinity Politics and the Persecution of Non-Heterosexual Russians.” NORMA. 12, no. 3–4 (2017): 302–18. doi:10.1080/18902138.2017.1312957.

Oliker, Olga. (2017). “Putinism, Populism and the Defence of Liberal Democracy.” Survival. 59, no. 1 (2017): 7–24. doi:10.1080/00396338.2017.1282669.

Özkan, Behlül. (2015). “Turkey’s Islamists: From power-sharing to political incumbency.” Turkish Policy Quarterly, 14, no. 1: 72-83.

Pain, Emil. (2016). “The Imperial Syndrome and Its Influence on Russian Nationalism.” In: The New Russian Nationalism: Imperialism, Ethnicity and Authoritarianism, 2000–2015, edited by Kolstø, Pål and Blakkisrud, Helge, 46–74. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Plagemann, Johannes & Destradi, Sandra. (2019). “Populism and Foreign Policy: The Case of India.” Foreign Policy Analysis, April 2019, Volume 15, Issue 2, Pages 283–301, https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/ory010

Ponarin, Eduard and Komin, Michael. (2018). “Imperial and Ethnic Nationalism: A Dilemma of the Russian Elite.” In: Russia Before and After Crimea: Nationalism and Identity, edited by Kolstø, Pål and Blakkisrud, Helge, 50–68. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Prosekov, S. (2018, July). “Confucianism and Its Influence on Deng Xiaoping’s Reforms.” In: 3rd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2018). Atlantis Press.

Putin, Vladimir. (2021). “Article by Vladimir Putin on the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” President of Russia website. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181 (accessed on April 11, 2024).

Putin, Vladimir. (2023). “Vladimir Putin meets with members of the Valdai Club: transcript of the Plenary Session of the 20th Annual Meeting.” Valdai Club. https://valdaiclub.com/events/posts/articles/vladimir-putin-meets-with-members-of-the-valdai-club-transcript-2023/ (accessed on April 11, 2024).

Shils, Edward. (1956). The Torment of Secrecy. The Background and the Consequences of American Security Policies. New York: The Free Press.

Tang, Wenfang. (2016). Populist authoritarianism: Chinese political culture and regime sustainability. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Taş, Hakki. (2018). “A history of Turkey’s AKP-Gülen conflict.” Mediterranean Politics, 23(3), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2017.1328766

Taş, Hakkı. (2022a). “Erdoğan and the Muslim Brotherhood: An Outside-in Approach to Turkish Foreign Policy in the Middle East.” Turkish Studies, 23, no. 5 (2022): 722–42. doi:10.1080/14683849.2022.2085096

Taş, Hakkı. (2022b). “The Chronopolitics of National Populism.” Identities, 29, no. 2 (2022): 127–45. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2020.1735160.

Tepe, Sultan and Chekirova, Ajar. (2022). “Faith in Nations: The Populist Discourse of Erdogan, Modi, and Putin.” Religions, 13, no. 5: 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050445

Teper, Yuri. (2015). “Official Russian Identity Discourse in Light of the Annexation of Crimea: National or Imperial?” Post-Soviet Affairs, 32 (4): 378–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2015.1076959

The Guardian. (2023). “The Observer view on Narendra Modi’s growing threat to democracy.” The Guardian. April 23, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/apr/23/the-observer-view-on-narendra-modi-growing-threat-to-democracy (accessed on April 11, 2024).

Therborn, Göran. (2021). “States, Nations, and Civilizations.” Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 14, 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-020-00307-1

Trenin, Dmitri. (2015). Rossiya i mir v XXI veke [Russia and the World in the 21st Century]. Moscow: Eksmo.

Uzer, Umut. (2020). “Conservative Narrative: Contemporary Neo-Ottomanist Approaches in Turkish Politics.” Middle East Critique. 29, no. 3: 275–90. doi:10.1080/19436149.2020.177044

Verkhovsky, Aleksandr and Pain, Emil. (2012). “Civilizational Nationalism: The Russian Version of the ‘Special Path.’” Russian Politics and Law. 50 (5): 52–86. https://doi.org/10.2753/RUP1061-1940500503

Wojczewski, Thorsten. (2019). “Populism, Hindu Nationalism, and Foreign Policy in India: The Politics of Representing ‘the People’.” International Studies Review. Volume 22, Issue 3, September 2020, pp. 396–422. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viz007.

Xinhua. (2021). “Seven years on, Xi’s vision of civilization inspires hope in world of uncertainties.” Xinhua. March 28, 2021. https://xinhuanet.com/english/2021-03/28/c_139840921.htm

Yang, Li. (2011). “Minorities, Tourism and Ethnic Theme Parks: Employees’ Perspectives from Yunnan, China.” Journal of Cultural Geography. 28(2), 311–38. doi:10.1080/08873631.2011.583444.

Yilmaz, Ihsan. (2021). Creating the Desired Citizens: State, Islam and Ideology in Turkey. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Yilmaz, Ihsan & Morieson, Nicholas. (2022). “Religious Populisms in the Asia Pacific.” Religions. 13(9):802. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090802

Yilmaz, Ihsan and Demir, Mustafa. (2023). “Manufacturing the Ummah: Turkey’s transnational populism and construction of the people globally.” Third World Quarterly, 44(2), 320–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2146578

Yilmaz, Ihsan & Morieson, Nicholas. (2023a). Civilizationalism. Religions and the Global Rise of Civilizational Populism. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9052-6_2

Yilmaz, Ihsan & Morieson, Nicholas. (2023b). Religions and the Global Rise of Civilizational Populism. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Yilmaz, Ihsan and Morieson, Nicholas. (2023c). “Civilizational Populism in Domestic and Foreign Policy: The Case of Turkey.” Religions. 14, no. 5: 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050631.