Please cite as:

Olivares-Jirsell, Jellen. (2024). “Recalibration, Not Austerity: Welfare States and the Struggle for Liberalism.” Populism & Politics (P&P). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). December 6, 2024. Doi: https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0044

Abstract

Welfare states have acted as societal equalisers. They have reduced poverty, improved living standards, promoted equality, and supported democracy. However, their alignment with market imperatives and exclusionary definitions of deservedness threatens the welfare state’s role as a social equalising force. This paper aims to diagnose a challenge facing welfare states through two arguments. The first is that four recalibrations have taken place within welfare states: settling for universality, redefining universality, outsourcing, and reducing public spending. These recalibrations aim for market compliance, savings, and competitiveness. The second is that welfare states may prevent unequal distributions and promote equity by focusing beyond universality and prioritising socially liberal policies. By examining OECD countries and beyond, the paper highlights the pitfalls: a myopic focus on universality exacerbates inequalities; neoliberal criteria that align welfare states with populism and lend credence to welfare chauvinism; and outsourcing and privatisation that increase costs without improving service quality, weakening democratic capacity due to reliance on private providers.

Keywords: Recalibration, welfare states, austerity, producerism, populism, welfare chauvinism

(Received June 7, 2024, Published December 6, 2024.)

By Jellen Olivares-Jirsell*

Introduction

The establishment of welfare states has significantly impacted societies. The incredible achievements in social equality that welfare states have created cannot be overlooked. The package of wealth redistribution, services, and programmes has successfully reduced poverty in the places where it has been implemented (Kenworthy, 1999), thereby improving the living standards of millions of people.[1]

Welfare states record of success includes transforming democracies’ form and character (King, 1987) by producing high levels of income and gender equality (Swank, 2000) as well as supporting the consolidation of democratic rule (Pestoff, 2006). The role of the welfare state as a societal equaliser and creator of a critically engaged populous, confident in challenging and scrutinising policy, is widely acknowledged and understood (Patrick, 2017); the inclusion of Target 1.3 – ‘Social Protection Systems for All’ in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) is evidence of this ideological consensus of welfare states as essential for society.

However, welfare states currently survive precariously and face the consistent and erroneous idea that deficits are always bad, and that the welfare state is an expensive luxury that can only exist in exchange for sacrificing economic competition(Wren-Lewis, 2018). They have nonetheless endured and—mostly—remained in place (King, 1987), lifting their populations out of poverty and protecting them from external shocks, especially during crises (Bhambra & Holmwood, 2018), but they sacrifice much in the process.

When we think about the most celebrated welfare systems, we may consider their universal provision. Our minds may also drift to generous parental leave, free healthcare, education, and support. Unfortunately, this rosy picture of welfare states describes a non-existent utopia, as even the most celebrated welfare states now face issues with their provision.

This paper makes two main points: First, welfare states are not retrenching due to austerity but are recalibrating to align more with market imperatives. This recalibration, often mistaken for austerity, has shifted the focus from real accountability to delivering provision. It has narrowed perceptions such that funding issues are considered the only reason welfare states struggle to support their citizens. Second, this paper argues against the conventional view of the universality of provision as a north star for welfare states. Instead, the analysis guides the argument by focusing beyond universality and towards the prioritisation of socially liberal policies. Specifically, welfare states may prevent unequal distributions and promote equity within universal welfare programs. In doing so, welfare states may also prevent populists and neoliberals from redefining their inclusion criteria. The specific dynamics of these redefinitions will also be elaborated upon.

The goal of this paper is not prescriptive; welfare states are as varied as countries. Hence, a generic solution would not address local needs. Alternatively, it highlights the maladies our communal abandonment of liberalism and prioritisation of market imperatives have caused.

The two main arguments challenge the idea that citizens should accept subpar support, as welfare states are adequately funded. Social spending takes up more than a quarter of the GDP of OECD countries (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2023). Instead, they argue that welfare states may effectively safeguard their citizens if liberal priorities precede market competition.

The paper challenges the notion that welfare states are expendable luxuries, advocating instead for a reimagined role beyond essential provision, which can address deeper societal needs beyond mere bodily survival. After providing an overview of the debate around social public expenditure, this point is demonstrated by examining changes in public spending, the move towards outsourcing, and the redefined criteria of deservedness. Using examples within the OECD and beyond, emphasising Northern European countries, the paper illustrates how welfare states are recalibrating rather than simply cutting back. It underscores the essential role of welfare states in protecting the most vulnerable and maintaining social stability. The paper also critiques overemphasis on universality, arguing that this metric alone can mask underlying inefficiencies and exclusions in welfare provision. Instead, it calls for a broader evaluation of welfare states based on their impact and outcomes, not just their coverage.

A Few Words on Welfare States and Austerity

Welfare states are complex and multifaceted, sometimes seen as burdens or saviours, expendable or essential depending on the observer. In a first understanding of the welfare state, as King (1987) described, the welfare state embodies non-market criteria. It exists only to provide essential public goods and services to gain or maintain at least minimal well-being standards in a population. In a compromise between capitalist and socialist ideologies, welfare states look after their citizens so that they can be part of a healthy, educated and capable society, with the added benefit that healthy, educated and capable individuals make great contributors to the financial markets and democracies (Begg et al., 2015; Crosland, 1964). This represents a mutually beneficial relationship between citizens, markets and states. Another view on the welfare state is that it is costly, inefficient, creates dependence on government, and burdens markets, hence needs transforming to serve the market, generate growth and benefit society through generalised economic prosperity (Alesina et al., 2019).

Neither the idealised nor vilified version of the welfare state exists. Welfare states compile liberal goals of social protection and betterment with older themes, including the ubiquitous condemnation of the ‘unworthy poor’. At one point, these notions were used to justify the ‘progressive opinion’ that saw eugenics as a legitimate tool for raising the general quality of the population (Pierson & Leimgruber, 2010).

Moreover, welfare states determine who is part of society and deserves safety and security. This creates a sense of inclusion and trust for those considered members. At the same time, those outside are excluded, fitting well with the political manifestos of populists (Bergman, 2022; Busemeyer et al., 2021). As Zakaria (2007) warns, liberalism, the progressive force behind inclusive and fair societies and democracies, which endorses social justice and the expansion of civil and political rights, has been slowly extracted from liberal institutions such as welfare states. These ideas over the deservedness of some over others led over thirty years ago, to coining the term ‘welfare chauvinism’ to describe some Norwegians and Danes’ belief that welfare services should be restricted to the country’s own (Andersen & Bjørklund, 1990). In short, welfare states are complex and multifaceted, capable of much good but also capable of reproducing and sustaining unfair structures.

In a purely economic sense, the welfare state costs countries large chunks of their GDP (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2023), and at times, when welfare states do not uphold liberal values, they can solidify or even widen societal cleavages (Kenworthy, 1999; Parolin et al., 2023). This means that despite the good they do, they are imperfect institutions that are both essential and need improvement.

Overall, welfare states are state institutions that deliver interventions that help a population achieve or maintain at least minimal well-being standards. Their aims, however, may vary. Variously, it focuses on protecting the population, the market, the societal order, or something else. These differences are defined by the social and political priorities governing the state at that moment in time, as the upcoming examples will shortly show. In truth, welfare states are intrinsically political entities, defining acceptable and deserving versions of their citizens and responding to political priorities as they occur. This means that welfare states are subject to the ebb and flow of politics and the changing norms around deservedness, the role of the state in individual life and the multiple political priorities of contemporary politics.

Among said political priorities, governments may be concerned with creating surpluses in their cyclical primary balance adjustments (austerity), requiring – among other measures – reduced social spending. As hinted in the introduction, the constant push and pull between economic and social needs have caused significant changes to welfare states; these economic forces permeate politics and democratic institutions. Austerity measures have been one of the most favoured economic interventions since the normalisation of neoliberal economics in the 1980s.

There are different forms of austerity measures governments can introduce. Although raising or decreasing taxes is part of the austerity arsenal (Union of International Associations, 2024), we have come to understand austerity to mean cuts in spending rather than tax adjustments. The general idea of austerity measures is to cut down on luxuries and unnecessary spending, work on paying back debt, and even create a surplus in the budget. However, especially in countries like the UK, the everyday use of austerity is almost always equated with spending cuts (The Guardian, 2024). It rarely includes consideration of tax increases or reductions in the public lexicon. This leads to a frequent conflation of austerity with cuts to the welfare state.

Despite this frequent confusion, austerity measures refer to policies that aim to reduce government budget deficits by decreasing spending but may also involve tax increases, decreases, or a combination of these. The creation of surplus or reduction of deficit that austerity measures aim to create can be pretty confusing, as at times, it may even include increasing funding of certain areas of the economy – for example, by providing subsidies to industries that are expected to create growth (GOV.UK, 2023) – and cuts in other areas not deemed to help with economic growth – typically social spending. However, it is essential to understand that austerity measures aim to reduce budget deficits.

The effectiveness of austerity policies is subject to much debate. According to Keynesian economists, since one person’s spending is another person’s income, reductions in government spending during economic downturns worsen economic crises (Fazzari et al., 2013). Further, these reductions pass down debt to the working classes (Blyth, 2013) and severely affect physical and mental health (Barr et al., 2015; Loopstra et al., 2016; Patrick, 2017). Others believe reducing government budget deficits through spending cuts is more effective than increasing taxes. They argue that such policies demonstrate a government’s financial discipline to creditors and credit rating agencies, making borrowing easier and less expensive (Alesina et al., 2019).

Austerity is engaged with here because welfare states are often written and discussed in relation to austerity. This is central to the argument about recalibration. Austerity means more than cuts to the social spending budget; it has become a shorthand for welfare states’ funding challenges. In this paper, it is put forth that the issue lies beyond cuts to public social spending and that austerity (colloquially understood as cuts to the welfare state) is not the cause of the perceived retrenchment of welfare states; instead, recalibration is.

This paper aims to diagnose a challenge facing welfare states. The idea that welfare states have been reduced to nothing due to a lack of funding is as pervasive as the idea that deficits are bad. Both these ideas have severe implications for welfare states and their operations. However, as this paper argues, the strategies adopted to keep welfare states alive are geared around four central recalibrations: settling for universality, redefining universality, outsourcing and monetising public provision and reducing public spending on social protection. All these recalibrations are, in one way or another, based on the idea that welfare states ought to comply with market imperatives, making savings and operating competitively. To analyse welfare state recalibration empirically, some examples of countries facing these challenges are reviewed to assess how these recalibrations have taken shape.

The Recalibration Strategies

Settling for and Redefining Universality

Welfare states are permanently forced to justify their existence based on market imperatives due to the pervasive idea that governments should always grow, maintain a surplus and avoid debt at all costs (Wren-Lewis, 2018). There is a consistent thread of welfare provision as a value-for-money exercise: citizens are trained and kept sheltered and healthy to become productive members of society, but these protections must always cost less than citizens produce.

Considering this, welfare states are constituted as providers of social protection floors, overlooking their potential role in promoting liberalism through equality (Swank, 2000) and democracy (Patrick, 2017; Pestoff, 2006). Following the UN’s SDG, welfare states have been correctly lauded as basic protection floors with universal distribution as a deterrent to poverty and inequality.

The absence of a safety net can predispose the most vulnerable populations to extreme poverty; thus, implementing a basic yet universal provision may effectively mitigate this risk. However, in welfare states that have (or aim to have) universal coverage of those deemed deserving, citizens miss out on the broader societal benefits that welfare states provide when they instead focus on basic universal provision. Moreover, inequality and poverty may go unnoticed in places where universality of coverage exists as long as universality alone is the metric used to assess our welfare state outcomes (Patrick, 2017).

A case in point is that of the Netherlands, a country with a very high social expenditure budget and one of the most celebrated welfare states in the world. This country, however, has the highest level of outsourcing of social provision globally (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2023). It is also a place with very high levels of wealth inequality (Van den Bossche, 2019), a growing opportunity gap in education based on ethnicity and socio-economic class and issues of accessibility for service users due to significant restrictions to cover, resulting in the duality of provision, known as welfare chauvinism (de Koster et al., 2013).

In the Netherlands, for-profit nursing home care is banned, but changes in the policy have enabled for-profit nursing homes to circumvent the for-profit ban. This leads to exclusionary practices. For example, selecting clients based on the severity of their disease and not hiring expensive staff for specialist care, then moving people out if they become too ill and need specialist care (Bos et al., 2020). Similarly, childcare was privatised in 2005 to make provision efficient. However, there is inequality in childcare use by family type, and the quality of provision has decreased since privatisation and outsourcing started (Akgunduz & Plantenga, 2014).

In the case of the Netherlands, the services are technically more widely available than before, at least in terms of spaces in nursing homes or childcare; thus, the universality of provision has yet to be challenged. However, even as the provision of nursing homes and childcare has increased since the private sector incursion (Akgunduz & Plantenga, 2014; Bos et al., 2020), the examples evidence, universality is caveated to exclude those very sick from nursing homes or certain family groups from childcare. In this case, it is clear that the goal of universality has been kept, but focusing only on universality alone obscures important aspects of accessibility for specific groups.

Sweden provides another example of this duality of high social expenditure with disparities in outcomes. This country has privatised and outsourced much of its schooling provision and now observes a significant drop in the performance of these schools (OECD, 2023; West, 2014). The metric of universality is met since Sweden provides universal coverage to its population (Janlöv et al., 2023). However, considering the performance variations between schools in low and high-income areas, especially since 2003 (OECD, 2015), the universal provision of education clearly evidences a Matthew Effect, whereby provision is most beneficial to those who need it the least (Bonoli & Fabienne, 2018). Besides the inequitable distribution of public goods, an additional challenge in the Swedish educational landscape is the establishment of lobbying. Private actors have evolved from holding purely economic roles to being strong political actors engaged in policymaking, adversely affecting transparency and democracy (Jobér, 2023). Moreover, this type of lobbyism can enhance existing socio-economic divisions, as schools with the capacity to lobby for more resources are also those in the wealthier areas.

The point here is not to minimise the achievements of welfare states; both the Netherlands and Sweden boast some of the best social well-being metrics in the world. Indeed, these two countries have some of the most acclaimed welfare systems in the world (Hutt, 2019; OECD, 2024a; OECD, 2024b). Sweden, particularly, was seen as the model for most welfare states in the post-war era for the rest of Europe. However, as the above examples show, the universality of public provision does not equate to better outcomes, and, at times, it may even perpetuate or exacerbate unequal societal constructions.

Moreover, the Netherlands and Sweden are not isolated cases. In the EU, native workers obtain the highest economic prosperity and employment returns from education, followed by EU workers, leaving non-EU workers last. Similar trends can also be observed in the US between natives and non-natives (Gamito, 2022). The universality of provision, therefore, does not signify equality in outcomes when inequity is built into the infrastructure of provision. Thus, universal provision may enhance societal cleavages and create or enhance a Matthew Effect.

This Matthew Effect exists in various forms in all welfare states (Heckman & Landersø, 2021; Pavolini & Van Lancker, 2018). If anything, the Netherlands and Sweden have been somewhat protected from adverse outcomes because of the societal duress and resilience created before these services were privatised and outsourced (OECD, 2018) and their goals were rearranged.

I have so far argued that welfare states have adopted universality as their central goal, even though focusing on universality conceals issues with exclusionary practices that may perpetuate and even enhance social crevices. I will build upon this argument on universality as a central goal and posit that, besides focusing on universality as a central goal, welfare states have also redefined universality, at least to some degree, due to producerism.

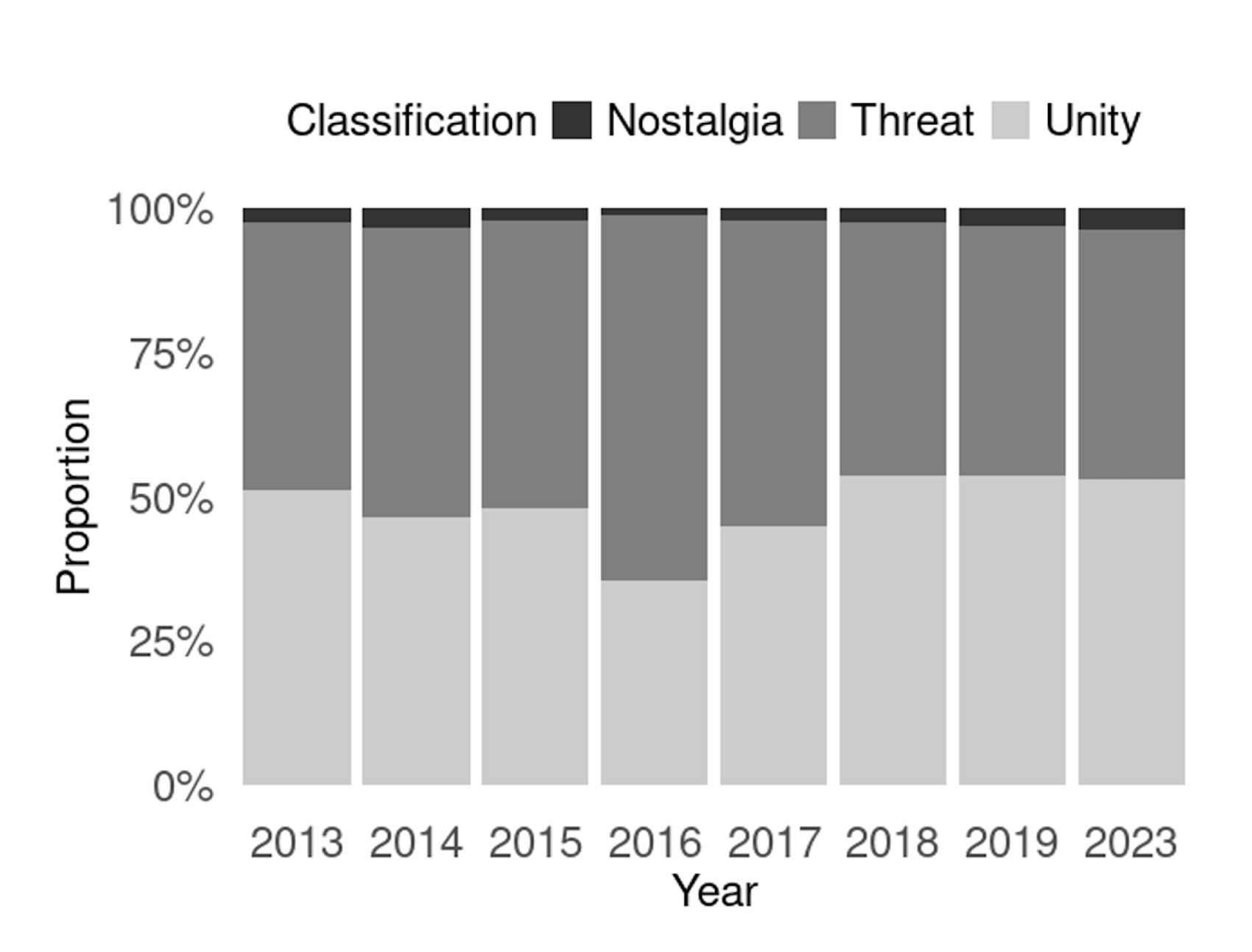

Producerism emphasises the importance of productive labour and the contributions of producers to society (Bergman, 2022). It often advocates for policies and attitudes that prioritise the interests of producers, such as workers, farmers, and entrepreneurs, over consumers or other groups. Producerism can manifest in various forms, including support for protectionist trade policies, subsidies for domestic industries, and efforts to promote self-sufficiency and national economic independence. It also lends credence to exclusionary forms of provision.

This emphasis on work participation within welfare programs dovetails producerism, underscoring the significance of productive labour and workers’ contributions to society through increasing adherence to workfare initiatives. Workfare refers to government programs or policies requiring individuals receiving welfare benefits to participate in some form of work or job training as a condition of assistance (Crisp & Fletcher, 2008). Unlike traditional welfare programs, which may provide financial support without a work requirement, workfare aims to promote self-sufficiency and reduce dependency on government assistance by encouraging recipients, via specific participation requirements, to gain job skills and enter the workforce. These requirements are often a combination of activities intended to improve the recipient’s job prospects and force the unemployed to contribute to society through unpaid or low-paid work comparable to community work (Ibid.). Forms of workfare programs include job placement services, subsidised employment, and mandatory community service or work assignments. Through workfare programmes, governments seek to enhance recipients’ employability and instil a sense of societal obligation to be productive members of society.

While employment can have a positive effect on well-being, the issue is not that the workfare approach may find jobs for those who want them; rather, it lies in that liberal protections are taken out of the equation as the main point of the welfare state, creating perverse incentives for the welfare state to become the surveyor and punisher of uncompliant citizens. This approach discourages fairness and social justice (Bonoli, 2010) because if all that matters is productivity, pensions serve little purpose, as does education beyond vocational training and services that cover sectors of the population that cannot access employment, such as those caring for family members and those with disabilities that prevent them from gaining employment. The issue is not that people will be encouraged to work but that this becomes a primary consideration of the welfare state, putting all others aside. In other words, welfare states have been recalibrated towards market imperatives and stripped of liberal notions.

Producerism can be said to be the ideological force behind workfare policies and is linked to welfare chauvinism (Van der Waal et al., 2013). Geva (2021), Cinpoeş and Norocel (2020) identify a producerist shift that coexists with welfare chauvinism in some post-communist countries. These authors argue that with the fall of the Soviet Union, post-communist countries like Poland, Hungary, and Romania aimed to shed anything resembling communism, hurriedly embracing neoliberal values to better fit into the rest of Europe. This symbolic return to Europe was so complete that the reconstructions of national membership and identity were combined with notions of entrepreneurship and self.

The vilification of people with low incomes is evidenced in Romania with the use of ‘asistat’ as a slur, a term referring to social assistance recipients; in Hungary, a Roma-specific welfare policy targeted Roma minorities who were construed as unwilling to work and carry their weight in society; and in Poland, this was articulated as lazy guests freeloading onto their hard-working hosts (Ibid.).

Other times, producerism can work to articulate the caveats of universality by allowing proxy exclusions. That is to say, producerism has redefined what universality is. Moral gymnastics have always surrounded universality considerations; at another time in history, being impious may have rendered someone unworthy of assistance and access to an almshouse (Lambeth Archives, 2024). What is novel about the redefinition of universality is that it is underpinned by neoliberal ideas, which claim to be unbiased and rational approaches to defining deservedness (Davies, 2014). By claiming rationality, producerism can help implement exclusionary policies that might otherwise create a political backlash by liberals and progressives.

Of course, it was a matter of economic competition. In that case, a purely homo-economicus approach to the ageing population challenges in many countries would involve welcoming migrants in any country they wished to work in, as they would contribute to the competitiveness of the nation and pay into the tax systems that fund the welfare state (Marois et al., 2020). However, producerism has been used to legitimise exclusionary welfare provisions that may ultimately operate against market efficiency. These neoliberal justifications for exclusion are most efficient as they sanitise and depoliticise prejudiced views under economic imperatives. The depoliticisation of prejudice enables governments to exclude significant portions of their residents from support. For instance, they may deny some individuals access to legal work and then claim those individuals are ineligible for assistance because they lack contributions or the required legal status.

Denmark, for example, currently has a two-tiered welfare system, one for Danish citizens and another for the rest (Van der Waal et al., 2013). Denmark prides itself on its universalist welfare regime; however, the universality of its provisions is truly exclusionary when considering that only some residents are included within this universal provision.

In the UK, the government, on the one hand, takes part in women empowerment campaigns (UN Women, 2023) and actively implements gender equality in the workplace regulations (UK Legislation, 2023) while at the same time actively restricting women from seeking help when experiencing domestic violence when they are not UK nationals and are stamped ‘no recourse to public funds’ in their passports. These actions can be justified under producerism because these groups are excluded only due to their lack of contributions (Pennings, 2020).

Producerism suggests that workers are virtuous and hard-working but are being squeezed by non-productive others both above them, such as bureaucrats, politicians, elites, bankers, and international capital, and below them, such as immigrants and undeserving poor who rely on benefits paid for by the labour of others. Moreover, it articulates and justifies divisions in a language many understand as unbiased and rational.

According to Larsen (2008), how welfare regimes are structured can impact how the public views those who are poor or unemployed. Van der Waal et al. (2013) have observed that various welfare regimes handle the provision/restriction duality differently but that, for the most part, producerist ideas of deservedness come to the fore. Guentner et al. (2016) find that groups framed as economically unproductive start to be considered a kind of human surplus and are, therefore, undeserving. In a UK example, a group of low-income individuals were pushed out of London’s social housing, resulting in their displacement because they were considered not to contribute sufficiently to the city to maintain their place in it (ibid.). Jingwei He (2022) finds the same concerning Chinese people’s attitudes toward welfare entitlements for rural-to-urban migrants.

Ward and Denney (2021) document a consistent rhetoric of abuse towards migrants framed around myths of them as less productive than nationals. Thus, we see here that producerist logic has been amalgamated with populism to create a type of welfare chauvinism that is both economic and cultural. This is crucial because, as argued, welfare states undergo producerist reconstructions whereby market-based logics are applied to social provision. This reconstructs the welfare state and the definition of universal provision upon caveated universal criteria – where universal does not mean everybody but those considered deserving. Hence, it is essential to re-examine welfare policies to ensure they promote fairness and social justice universally.

This section has discussed the evolution and challenges of welfare states, with a particular focus on the idea of universality in social protection. The argument is that welfare states have increasingly prioritised market-driven goals such as productivity and cost-efficiency over liberal objectives like equality and democracy. This shift has led to welfare systems that, while offering universal social protection, may fail to address underlying issues of inequality and poverty. Additionally, producerism was introduced as a factor contributing to the narrow and exclusive redefinition of universality. It rationalises social provisions that are only accessible to those considered deserving based on their productivity.

Outsourcing, Monetising and Reducing Public Spending on Social Protection

Thus far, this paper has mentioned privatisation and outsourcing only in relation to the universality of provision. Welfare states have undergone recalibrations that have made them settle for the simple goal of extended coverage. However, this may conceal issues with the quality of provision. I have argued that welfare states have always had an exclusionary criterion of deservedness disguised as logical and unbiased; the current iteration has been based on economic competition, best encapsulated under producerism. This has lent credence to policies of exclusion that affect the range, coverage and quality of welfare provisions.

In this section, I argue that welfare states have become privatised and outsourced to continue to exist. In the process, they have prioritised market imperatives instead of the liberal protections liberal democracies declare to prioritise. Nevertheless, this shift has not necessarily resulted in cost savings, improved service quality, or decreased public spending.

Public-private partnerships are becoming increasingly popular among governments to finance, design, build, and operate infrastructure projects and outsource goods and services, sometimes fully delivered by third parties but financed by governments (Jobér, 2023). The idea that the private sector is more efficient than the public sector and hence services ought to be outsourced, or else be done poorly and at more cost by the state, has prompted commissioning and subcontracting structures that are not necessarily more supportive of people’s needs, as I will shortly elaborate. Moreover, these outsourced services are not ipso facto cheaper than direct provision. This has resulted in for-profit companies becoming the primary or exclusive providers of public employment services in several countries (McGann, 2023) and failing to deliver the expected reduction in public spending on social protection.

Between 2005 and 2010, the total value of partnership projects in low and middle-income countries more than doubled (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2023). In OECD countries, around 36 per cent of total general spending is dedicated to public social protection, of which around 9 per cent is outsourced to private providers (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2023). In other words, a significant portion of OECD countries’ GDP is outsourced to the private sector. Swank (2000) argues that the structural transformations of welfare states include privatisation, decentralisation of authority, segmentation of benefit equality, and an increased emphasis on outsourcing provisions to non-state actors such as charities or private organisations through publicly commissioned services and are taking place worldwide. These changes align social policy with market-oriented values, emphasising work and market efficiency.

Whether these changes can be considered efficient depends on their goal. A 2018 OECD report showed that the rationale for privatising public provisions has mainly been geared towards economic stabilisation, improving the efficiency of the markets, or raising fiscal resources. The criteria for privatisation are based on two critical assumptions. First, it assumes that private markets are the most efficient way to provide public services. Second, it assumes that privatisation is the default option; those against it are tasked to prove why public services should remain state-owned (OECD, 2018).

With that in mind, the goal has been largely achieved if the rationale for privatising public provision is to improve market structures or economic efficiency. The state has effectively subsidised the private sector by providing extensive and profitable government contracts. Public sector privatisation and outsourcing have created millionaires and significant money transfers from the public to the private sector, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lilly et al., 2020).

The OECD report is interesting because it presents how disjointed the rationales for privatisation are from public protection. The report shows evident market prioritisation over the protection of liberal values that countries in the OECD area may otherwise claim to prioritise.

The second argument in this section is that the goal of reducing public spending on social protection through privatisation and outsourcing of social protection has not materialised. As shown in the examples above, public spending is at its highest despite recent fluctuations. While raising fiscal resources by making savings in social public spending may be one of the rationales provided for privatisation, the outcomes do not necessarily give the taxpayer the opportunity for a discount (OECD, 2018). Countries continue to dedicate large sections of their GDP to social spending, but the savings expected due to the privatisation and monetisation of welfare provision have not been fulfilled. Moreover, welfare provision has not improved either; headlines abound about funding losses and service deterioration (Bambra, 2019; Boylan & Ho, 2017; Konzelmann, 2019; Pentaraki, 2017).

This increase in privatisation and outsourcing of public provision means that the state has less direct control over the provision of public services but oversees the delivery of these services through monitoring and surveillance. Many local authorities in the UK have shifted to commissioning-only or at least commissioning-heavy provisions (Dickinson, 2014), with staff overseeing the contracts and ensuring goals are met. Commissioning aims to decrease the government’s involvement in providing services. This encourages public authorities to act as enablers with a strategic oversight function that assesses the needs of defined populations and the outcomes delivered by third parties. The commissioning economy comprises an extensive network of public bodies, private firms, and third sector organisations that are variously involved in providing services (Macmillan & Paine, 2021). The state has thus reconfigured its mission as a regulator rather than a direct provider of welfare and other crucial services (Yeung, 2010).

This shift from rowing to steering (Osborne & Gaebler, 1992) has had two notable outcomes; the first is that, as we have seen, no saving has occurred. Since 1995, government social spending has increased in many countries (The World Bank, 2024). While several countries appear to be decreasing their social spending recently, they have maintained a very high level of social expenditure (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2023). Governments still have to employ people to manage the commissioned services, and these private contracts are not cheaper for the public purse or better for the service user, as seen in the Swedish and Dutch examples.

The Netherlands is a valuable reminder of this reality as the country has a very high social expenditure budget and the highest level of outsourcing of social provision globally (ibid.). It has been very active in privatisation for around 30 years; between 1980 and 2015, the expenditure on health was around 5 per cent. Around the late 1990s, when privatisation and outsourcing began in earnest, the country spent around 1% less on health than it had a decade before. However, at the beginning of the 2000s, the number increased to around 6 per cent, peaking at 6.5 per cent in 2015, and currently at around 5.7 per cent (OECDc, 2024).

At the same time, the service provision became conditional and monetised, resulting in all persons residing in the Netherlands and all non-residents working in the Netherlands being required to buy private healthcare insurance (Pennings, 2020). In short, the Netherlands pays more now for a health provision that requires insurance premiums and deductibles (co-pays) to access (Government of the Netherlands, 2024). This diminished (in terms of accessibility) health provision is paid twice, once through taxes and again directly when patients require provision.

The second notable outcome is the loss of democratic capacity. The capacity-building exercise of democratic institutions occurs daily when providing goods and services to its citizens. When managing these social goods and services is outsourced, so is the daily exercise of liberal provision. As a result, welfare states lose their ability to maintain the liberal institutions that underpin democracies. Capacity building is essential for successfully navigating, adapting, and flourishing in a rapidly changing world (United Nations, 2024). When this is outsourced, governments become dependent on private provision and lose the ability to deal with complex challenges.

In the UK, outsourcing accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the government contracted various private providers to manage the logistics of and store personal protective equipment, the national drive-in testing centres and super-labs, run the contact tracing programme, build the COVID-19 datastore and onboard returning health workers (British Medical Association (BMA), 2020). The BMA report (Ibid.) shows that continued outsourcing of the national health service in the UK significantly limited the government’s ability to mount a coordinated response during the public health emergency. Paradoxically, outsourcing was used to fill gaps created by sustained outsourcing and privatisation.

Of course, the changes in privatisation and outsourcing of public provision are not unique to the Netherlands, the UK, or health. Indeed, this process is taking place widely (Jobér, 2023) and over various areas of social protection spending (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2023). Meanwhile, private sector involvement in public provision trend is on the rise with no apparent slowdown on the horizon (British Medical Association, 2020; OECD, 2018); all the while, public spending on social protection has stayed at very high levels, and state capacity has become dependent on the private sector.

This section has examined the trend of privatisation and outsourcing in welfare states, arguing that these practices have shifted the focus from liberal protections to market imperatives. Welfare states, driven by the belief in the private sector’s efficiency, have increasingly turned to public-private partnerships and outsourcing to deliver public services. This shift has not necessarily resulted in cost savings or improved service quality. Instead, as commissioning and outsourcing increase, so does public spending, with significant portions of GDP now directed to private providers, furthering a disconnect between the goals of economic efficiency and the quality of social protection. Welfare states have increasingly become commodification engines, prioritising market-driven goals such as productivity and cost-efficiency over liberal objectives such as equality and democracy.

Moreover, the reliance on private sector provision has undermined democratic capacities by reducing the state’s direct control over public services and eroding the daily exercise of liberal provision. This dependence on private providers has also compromised the state’s ability to handle complex challenges. Privatisation and outsourcing have thus not achieved the intended economic efficiencies or service quality improvements. Instead, public spending remains high, and state capacity has become increasingly reliant on the private sector, raising concerns about the future of social protection and democratic governance.

Conclusion

Welfare states are complex and multifaceted. They have inherent issues, and their goals of social betterment coexist with older themes, including the condemnation of the ‘unworthy poor.’ Moreover, welfare states are costly, consuming significant portions of GDP, and can sometimes reinforce societal divides instead of bridging them. Welfare states are intrinsically political, defining acceptable and deserving versions of citizens.

However, they are also essential for equality and democracy and for lifting many out of poverty. This paper acknowledged that welfare states’ strengths are more potent than their weaknesses and aimed to identify the nature of the challenges facing them today.

Welfare states have fared rough neoliberal waters in some ways through recalibration strategies. By submitting to market imperatives and focusing on and redefining universality, outsourcing, and monetising public provision, they have managed to keep their place in society. However, these recalibrations have not met the promised savings to the taxpayer nor the desired liberal outcomes in protecting society’s most vulnerable. Welfare states have kept their places in society, but much has been lost in adapting to market imperatives.

These recalibrations have aligned welfare states with market imperatives, emphasising cost savings and competitive operation and forfeiting liberal priorities in the following ways. For example, focusing solely on universality has obscured and exacerbated existing inequalities. Second, by redefining universality through neoliberal criteria, welfare states have lent credence and inadvertently aligned themselves with the populist ‘us versus them’ criterion of difference. Third, outsourcing has led to higher costs without improved service quality. Lastly, such outsourcing has eroded democratic capacity as governments become dependent on private providers, losing the ability to manage social challenges independently.

In this paper, two main points were presented. The first is that the welfare state is undergoing recalibration, not austerity. This was illustrated through explanations around social public expenditure, the move towards outsourcing, and the redefined criteria of deservedness. Despite some small recent dips, the expenditure has increased overall. Social public spending is among the highest it has ever been, but what has changed is how it is spent. With that in mind, the issue is not austerity. Thus, the problem is that social spending is financing the private sector through outsourcing contracts instead of focusing on improving its provision.

As articulated here, welfare states are not luxuries; they can reduce poverty, protect citizens against shocks, and embolden citizens to be capable, educated, and healthy protectors of democracy, especially during crises and economic downturns. However, the essential liberal values that welfare states aim to protect are compromised when market imperatives become the priority. The public sector has effectively subsidised the private sector through commissioning contracts that do not necessarily provide cheaper or better support for service users compared to what governments can offer. This is because the primary incentive for the private sector is profit-making and contract renewal rather than focusing on reducing poverty and inequalities, protecting citizens from shocks, or empowering citizens to be capable, educated, and healthy protectors of democracy.

We now know that outsourcing and privatising public provision have not resulted in savings for the taxpayer; decades of data show that welfare states are not spending less (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2023). However, when citizens inquire about what has happened to their community services, schools, or health services, a word frequently used is austerity. Used colloquially, austerity refers to budget cuts for public social spending. Still, if these budgets have expanded, then this means that the challenges faced by welfare states are not only due to austerity.

In the second point, I have demonstrated that governments’ focus on the universality of welfare states is at the expense of achieving liberal goals. The universality of provision, as shown, may create the illusion that it is worth having a welfare state just for its own sake, even if it barely functions as a social equaliser and poverty-reducing tool.

I reiterate that my argument is not for eliminating universality in welfare states but rather for implementing policies that prevent the unequal distribution of benefits within universal welfare programs. Specifically, I posited that governments might reconsider financing the private sector via outsourcing contracts and instead exercise their liberal muscle by working on improving their provision, not just coverage.

So much institutional knowledge has been lost through outsourcing, knowledge that may help adapt services to assist better those slipping through the cracks. By creating or rebuilding their institutional capacity, governments are better placed to deal with emerging crises instead of relying on the private sector, as was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic. By engaging with and prioritising market imperatives, liberal values have been put to one side, and producerism has entered welfare provision, shaping welfare programmes and objectives. However, this focus on universality is a recalibration emerging from an erroneous understanding that welfare states must trim their goals due to limited funding.

The two arguments presented challenge the idea that citizens must settle for scraps, as welfare states are suitably funded to provide the required provisions. Since the issue is not austerity, I suggest that citizens consider whether their welfare states suitably protect them under the current provision or if market imperatives have been prioritised.

The recalibration of welfare states often comes at the expense of service quality, equity, and democratic capacity, raising concerns about welfare states’ future direction. In truth, citizens are paying dearly for a poor product and are losing their capacity as capable, educated, and healthy protectors of democracy to reject a poor deal.

Confusion over the real cause of welfare state retrenchment obscures potential solutions. This diagnosis and the suggestion that welfare states may look beyond universality and stop working towards market imperatives are more straightforward said than done, as welfare states are intrinsically political and politicised entities. Still, I propose that by suitably diagnosing the issue, societies might have a fighting chance to save welfare states and, in turn, strengthen liberal democracies

(*) Jellen Olivares-Jirsell is a Doctoral candidate in Politics at Kingston University London. Her scholarly contributions include publications in the Global Affairs and Populism journals. Research activities include roles with the Trust Lab project at Swansea University and EUscepticOBS and Populism in the Age of COVID-19 at Malmo University. Research interests encompass politics, norms and ideologies, populism, neoliberalism, welfare states, trust, and polarization.

References

Andersen, J., & Bjørklund, T. (1990). Structural Changes and New Cleavages: The Progress Parties in Denmark and Norway. Acta Sociologica, 33(2), 195-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169939003300303

Akgunduz, Y., & Plantenga, J. (2014). Childcare in the Netherlands: Lessons in privatisation. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 22(3), 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2014.912900

Alesina, A., Favero, C. & Giavazzi, F. (2019). Austerity: When It Works and When It Doesn’t. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bambra, C. (2019). Health in Hard Times: Austerity and Health Inequalities. Bristol: Policy Press.

Barr, B., Kinderman, P., & Whitehead, M. (2015). Trends in Mental Health Inequalities in England During a Period of Recession, Austerity and Welfare Reform 2004 to 2013. Social Science & Medicine, pp. 147, 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.009

Begg, I., Mushövel, F., & Niblett, R. (2015). The Welfare State in Europe, Visions for Reform. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/20150917WelfareStateEuropeNiblettBeggMushovelFinal.pdf

Bergman, M., (2022). Labour Market Policies and Support for Populist Radical Right Parties: The Role of Nostalgic Producerism, Occupational Risk, and Feedback Effects. European Political Science Review, 14(4), 520–543. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577392200025X

Bhambra, G., & Holmwood, J. (2018). Colonialism, Postcolonialism and The Liberal Welfare State. New Political Economy, 23(5), 574-587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1417369

Blyth, M. (2013). Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bonoli, G. (2010). The political economy of active labour market policy. Working Papers on the Reconciliation of Work and Welfare in Europe, RECWOWE Publication, Dissemination and Dialogue Centre, Edinburgh. https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/3290/REC-WP_0110_Bonoli.pdf

Bonoli, G., & Fabienne, L. (2018). Good Intentions and Matthew effects: Access Biases in Participation in Active Labour Market Policies. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(6), 894-911. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1401105

Bos, A., Kruse, F., & Jeurissen, P. (2020). For-Profit Nursing Homes in the Netherlands: What Factors Explain Their Rise? International Journal of Health Services, 50(4), 431-443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731420915658

Boylan, R., & Ho, V. (2017). The Most Unkindest Cut of All? State Spending on Health, Education, And Welfare During Recessions. National Tax Journal, 70(2), 329–366. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2017.2.04

British Medical Association. (2020). The Role of Private Outsourcing in the COVID-19 Response. British Medical Association. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/3576/the-role-of-private-outsourcing-in-the-covid-19-response.pdf

Busemeyer, M., Rathgeb, P., & Sahm, A. (2021). Authoritarian Values and the Welfare State: The Social Policy Preferences of Radical Right Voters. West European Politics, 45, 77 – 101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1886497

Crisp, R., & Fletcher, D. (2008). A Comparative Review of Workfare Programmes in the United States, Canada and Australia. Department for Work and Pensions. https://www.shu.ac.uk/-/media/home/research/cresr/reports/r/review-workfare-usa-canada-australia.pdf

Crosland, C. (1964). The Future of Socialism. Michigan: University of Michigan.

Davies, W. (2014). Neoliberalism: A Bibliographic Review. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(7/8), 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414546383

de Koster, W., Achterberg, P., & van der Waal, J. (2013). De Koster, W., Achterberg, P. and van der Waal, J. (2013). ‘The New Right and the Welfare State: The Electoral Relevance of Welfare Chauvinism and Welfare Populism in the Netherlands’,. International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale de Science Politique, 34(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512112455443

Dickinson, H. (2014). Public Service Commissioning: What Can be Learned From the UK Experience? Australian Journal of Public Administration, 73(1), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12060

Fazzari, S., Ferri, P., Greenberg, E., & Variato, A. (2013). Aggregate Demand, Instability, and Growth. Review of Keynesian Economics, 1(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-011-9277-8

Gamito, C. (2022). Returns-to-Education Gaps Between Native and Migrant Workers: The Influence of Economic Integration on Their Drivers. Are Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) an Effective Remediation Tool? A Case Comparison: Italy, Germany, Denmark and Cyprus. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, 56, 63–81. https://doi.org/10.12775/bgss-2022-0013

Geva, D. (2021). Orban’s Ordonationalism as Post-Neoliberal Hegemony. Theory, Culture & Society, 38(6), 71–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276421999435

GOV.UK. (2023). Billions of Investments for British Manufacturing to Boost Economic Growth. Retrieved 07 03, 2024, from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/billions-of-investment-for-british-manufacturing-to-boost-economic-growth

Government of the Netherlands. (2024). Standard Health Insurance. Retrieved 09 05, 2024, from https://www.government.nl/topics/health-insurance/standard-health-insurance

Guentner, S., Lukes, S., Stanston, R., Vollmer, B., & Wilding, J. (2016). Bordering Practices in the UK Welfare System. Critical Social Policy, 36(3), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018315622609

Heckman, J., & Landersø, R. (2021). Lessons for Americans from Denmark About Inequality and Social Mobility. Labour Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2021.101999

Hutt, R. (2019). Sweden is a Top Performer in Well-Being. Here’s Why. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/05/sweden-is-a-top-performer-on-well-being-here-s-why/

Janlöv, N., Blume, S., Glenngård, A., Hanspers, K., Anell, A., & Merkur, S. (2023). Sweden: Health System Review 2023. Health Systems in Transition, 25(4). https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/sweden-health-system-review-2023

Jingwei He, A. (2022). The Welfare Is Ours: Rural-to-Urban Migration and Domestic Welfare Chauvinism in Urban China. Journal of Contemporary China, 31(134), 202-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2021.1945735

Jobér, A. (2023). Private Actors in Policy Processes. Entrepreneurs, Edupreneurs and Policyneurs. Journal of Education Policy, 39(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2023.2166128

Kenworthy, L. (1999). Do Social-Welfare Policies Reduce Poverty? A Cross-National Assessment. Social Forces, 77(3), 1119–1139. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/77.3.1119

King, D. (1987). The State and the Social Structures of Welfare in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Theory and Society, 16(6), 841–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138071

Konzelmann, S. (2019). Austerity. Cambridge, UK : Polity.

Lambeth Archives. (2024). Behind the Blue Doors. Brixton, London: Lambeth Archives. https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/events/behind-blue-doors

Larsen, C. (2008). The Institutional Logic of Welfare Attitudes: How Welfare Regimes Influence Public Support. Comparative Political Studies, 41(2), 145–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006295234

Lilly, A., Tetlow, G., Pope, T., & Davies, O. (2020). The Cost of Covid-19 The impact of Coronavirus on the UK’s Public Finances. London: Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/cost-of-covid19.pdf

Loopstra, R., McKee, M., Katikireddi, S., Taylor-Robinson, D., Barr, B., & Stuckler, D. (2016). Austerity and Old-Age Mortality in England: a Longitudinal Cross-Local Area Analysis, 2007–2013. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 109(3), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076816632215

Macmillan, R., & Paine, A. (2021). The Third Sector in a Strategically Selective Landscape – The Case of Commissioning Public Services. Journal of Social Policy, 50(3), 606–626. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279420000355

Marois, G., Bélanger, A., & Lutz, W. (2020). Population Aging, Migration, and Productivity in Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences PNAS, 117(14), 7690–7695. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1918988117

McGann, M. (2023). The Marketisation of Welfare-to-Work in Ireland Governing Activation at the Street-Level. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Norocel, C., & Cinpoeş, R. (2020). Nostalgic Nationalism, Welfare Chauvinism, and Migration Anxieties in Central and Eastern Europe. In C. Norocel, A. Hellström, & M. Jørgensen (Eds.), Nostalgia and Hope: Intersections between Politics of Culture, Welfare, and Migration in Europe. Springer open /IMISCOE research series. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41694-2_4

OECD. (2015). Improving Schools In Sweden: An OECD Perspective. OECD.

OECD. (2018). Privatisation and the Broadening of Ownership of State-Owned Enterprises 2008-2018. OECD. Retrieved 09 09, 2024, from https://www.oecd.org/corporate/Privatisation-and-the-Broadening-of-Ownership-of-SOEs-Stocktaking-of-National-Practices.pdf

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results: Factsheets – Sweden. OECD. Retrieved 09 09, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en.

OECD. (2024a). Sweden OECD Better Life Index. OECD. Retrieved 09 09, 2024, from https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/sweden/

OECD. (2024b). Expenditure for Social Purposes by Branch. OECD. Retrieved 09 09, 2024, from https://web-archive.oecd.org/temp/2024-06-24/63248-expenditure.htm

OECD. (2024c). Netherlands OECD Better Life Index. OECD. Retrieved 09 09, 2024, from https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/netherlands/

Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2023). Government Spending. Retrieved 04 16, 2024, from https://ourworldindata.org/government-spending

Osborne, D., & Gaebler, T. (1992). Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector. New York: Penguin Books.

Parolin, Z., Desmond, M., & Wimer, C. (2023). Inequality Below the Poverty Line since 1967: The Role of the U.S. Welfare State. American Sociological Review, 88(5), 782–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224231194019

Patrick, R. (2017). For Whose Benefit? The Everyday Realities of Welfare Reform. Bristol: Bristol: University Press.

Pavolini, E., & Van Lancker, W. (2018). The Matthew Effect in Childcare Use: A Matter of Policies or Preferences? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(6), 878-893. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1401108

Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010). Recombinant Workfare, Across the Americas: Transnationalizing “Fast” Social Policy. Geoforum, 41(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.01.001

Pennings, F. (2020). Migrants’ Access to Social Protection in the Netherlands. In J. Lafleur, & D. Vintila (Eds.), Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 1) Comparing Access to Welfare Entitlements. IMISCOE Research Series.

Pentaraki, M. (2017). “I Am in a Constant State of Insecurity Trying to Make Ends Meet, like Our Service Users”: Shared Austerity Reality between Social Workers and Service Users—Towards a Preliminary Conceptualisation. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(4), 1245–1261. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw099

Pestoff, V. (2006). Citizens and Co-Production of Welfare Services: Childcare in Eight European Countries. Public Management Review, 8(4), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030601022882

Pierson, C., & Leimgruber, M. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State. In F. Castles (Ed.), Intellectual Roots (pp. 32–44). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00775_1.x

Swank, D. (2000). Social Democratic Welfare States in a Global Economy: Scandinavia in Comparative Perspective. In R. Geyer, C. Ingebritsen, & J. Moses (Eds.), Globalization, Europeanization and the End of Scandinavian Social Democracy?. London: Palgrave Macmillan

The Guardian. (2024). The latest News and Comments on Economic Austerity. Retrieved 07 03, 2024, from https://www.theguardian.com/business/austerity

The World Bank. (2024). DataBankWorld Development Indicators. The World Bank. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

UK Legislation. (2023). The Equality Act 2010 (Gender Pay Gap Information) Regulations 2017. Retrieved 05 18, 2023, from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2017/9780111152010

UN Women. (2023). Partner spotlight: United Kingdom. Retrieved 05 17, 2023, from https://www.unwomen.org/en/partnerships/donor-countries/top-donors/united-kingdom

Union of International Associations. (2024). Austerity | The Encyclopedia of World Problems. Retrieved 04 19, 2024, from http://encyclopedia.uia.org/en/problem/austerity

United Nations. (2024). Capacity-Building. Retrieved 06 05, 2024, from https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/capacity-building

Van den Bossche,, C. (2019). Inequalities in the Netherlands. Women Engage for a Common Future. https://www.sdgwatcheurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/10.1.a-factsheet-NL.pdf

Van Der Waal, J., De Koster, W., & Van Oorschot, W. (2013). Three Worlds of Welfare Chauvinism? How Welfare Regimes Affect Support for Distributing Welfare to Immigrants in Europe. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 15(2), 164-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2013.785147

Ward, P., & Denney, S. (2022). Welfare Chauvinism Among Co-Ethnics: Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment in South Korea. International Migration, pp. 60, 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12937

West, A. (2014). Academies in England and Independent Schools (‘Fristående Skolor’) in Sweden: Policy, Privatisation, Access and Segregation. Research Papers in Education, 29(3), 330–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2014.885732

Wren-Lewis, S. (2018). ‘Mediamacro’ Why the News Media Ignores Economic Experts. In The Media and Austerity. London: Routledge.

Yeung, K. (2010). The Regulatory State. In R. Baldwin (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Regulation (pp. 64–84). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199560219.001.0001

Zakaria, F. (2007). The Future of Democracy. Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad. New York: W.W. Norton.

[1] Acknowledgement: I am grateful for the feedback this paper received during and after the workshop and the anonymous reviewers. I am also incredibly thankful for Hannah Geddes’s full engagement as a discussant.