Chile’s November 16, 2025 presidential vote has produced an unprecedented runoff between José Antonio Kast and Jeannette Jara, crystallizing what Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure calls a historic ideological rupture. Speaking to ECPS, he warns that Chile’s shift must be understood within a broader continental realignment: “A new right-wing alliance is emerging in Latin America—and democracy will take a toll.” According to Larrabure, this bloc is not restoring old authoritarianism but “reinventing democracy—and it’s working.” Kast’s coalition embodies a regional “Bolsonaro–Milei playbook,” powered by what Larrabure terms “rule by chaos,” amplified by compulsory voting and disinformation ecosystems. Meanwhile, the Chilean left enters the run-off severely weakened—“the final nail in the coffin” of a long cycle of progressive contestation.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

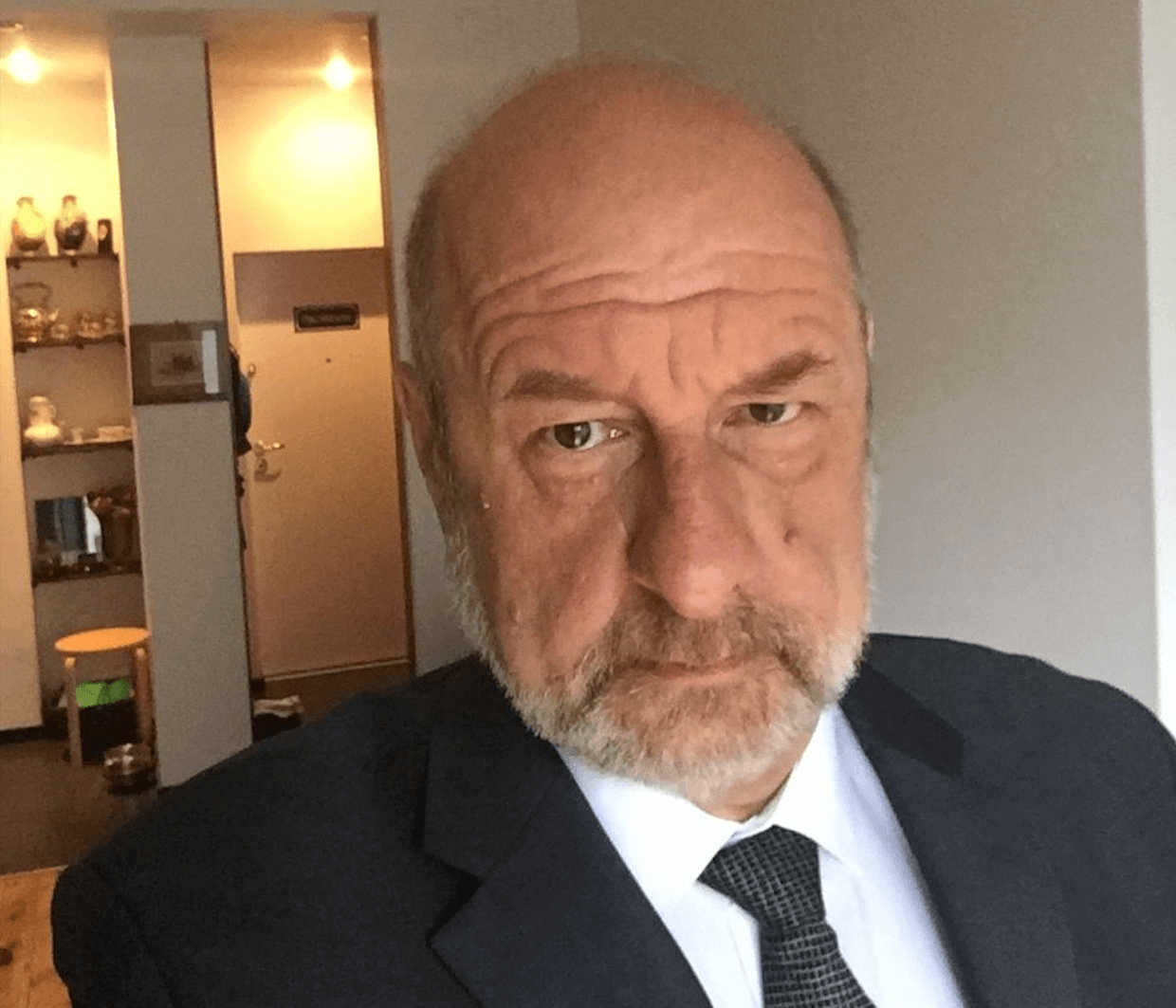

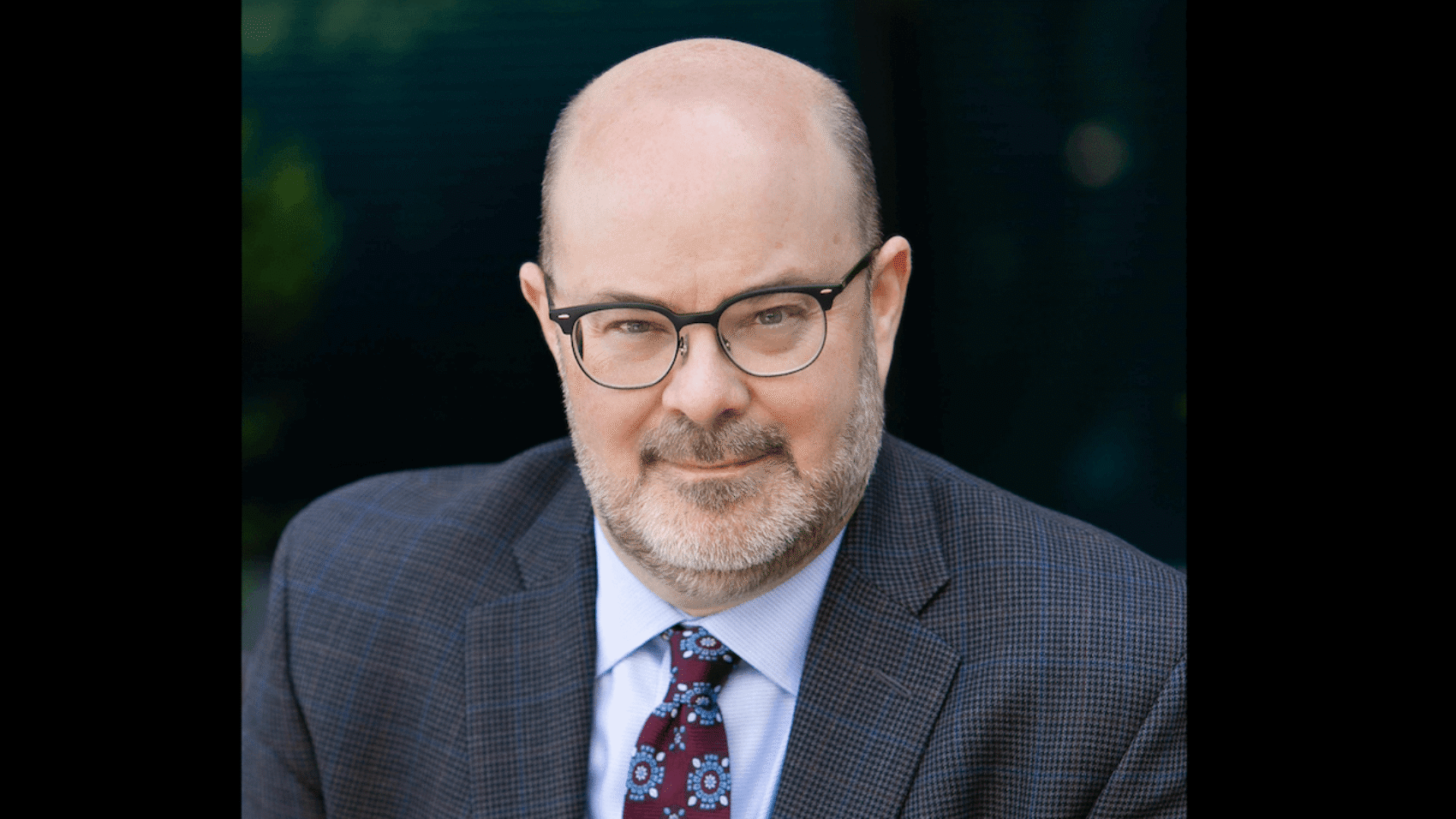

Chile’s first-round presidential election on November 16, 2025 has produced one of the most consequential political realignments in the country’s post-authoritarian history. For the first time since return to democracy, voters are confronted with a stark extreme-right–versus–Communist runoff between José Antonio Kast and Jeannette Jara—an outcome that crystallizes the profound fragmentation and ideological polarization reshaping Chilean politics. Against this backdrop, the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS) spoke with Associate Professor Manuel Larrabure, a scholar of Latin American Studies at Bucknell University, whose research on Latin American political transformations offers a critical vantage point on Chile’s current trajectory. As he notes, the 2025 election marks not merely a national turning point, but a regional one: “A new right-wing alliance is emerging in Latin America—and democracy will take a toll.”

Dr. Larrabure situates Chile’s sharp bifurcation within a wider continental pattern of right-wing recomposition, one increasingly linked across Argentina, Ecuador, Bolivia, and beyond. This emergent bloc, he argues, is not driven by nostalgia for past authoritarianism but by a more adaptive and experimental form of illiberal governance. “They are not trying to destroy democracy,” he stresses. “They are trying to reinvent it—and it’s working.” Kast’s coalition, he suggests, fits squarely within this “Bolsonaro–Milei playbook,” but is tempered by Chile’s more conservative political culture. Still, the danger is clear: the right is forging a novel repertoire of power in an era defined by global monopolies, weakened party systems, and disoriented progressive forces.

One of Dr. Larrabure’s most striking insights concerns what he calls the right wing’s mastery of “rule by chaos.” Rather than relying solely on repression, the contemporary right activates social anxieties—around crime, immigration, and insecurity—to mobilize working-class discontent. This dynamic has been amplified, he argues, by Chile’s reintroduced system of compulsory voting, which “absolutely turned out working in favor of the right wing” during the failed constitutional plebiscite of 2022. Social media ecosystems have further strengthened the right’s influence by “creating an atmosphere of general misinformation and chaos, communicational chaos and informational chaos, in which they can operate with ease.”

By contrast, the Chilean left enters the 2025 runoff severely weakened. Dr. Larrabure describes the election as “the final nail in the coffin of a cycle of contestation” that began with the 2006 school protests, peaked in the 2011 student movement, and culminated in the aborted constitutional process of 2019–2022. Progressive forces, he contends, have struggled to translate grassroots innovation into institutional power, hampered in part by diminished capacities for popular education and an unresolved tension between participatory democratic ideals and party-led governance.

Looking ahead, Dr. Larrabure foresees intensified social conflict but also the latent possibility of democratic renewal. Chile’s constitutional debate, he argues, is effectively over; yet social movements will continue to respond. Ultimately, the question is whether they can forge a transformative project capable of “learning from the mistakes of the past” amid an increasingly securitized and polarized political landscape.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Associate Professor Manuel Larrabure, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

Not Pinochet Reborn—but Something New

Professor Manuel Larrabure, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: Chile’s first round of presidential elections on November 16, 2025, produced an extreme-right-versus-Communist runoff unprecedented since the transition to democracy. How do you interpret this sharp ideological bifurcation in light of your work on the fragmentation of both left and right coalitions in Latin America?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: This is a very interesting question, and indeed, there is a bifurcation—a gap—between the Communist Party candidate, Jeannette Jara, and the right-wing candidate. But we need to unpack some assumptions here, because we can easily fall into narratives that are not quite accurate. So let me start with the Communist Party first, and then I’ll talk about the right wing.

The Communist Party has a very long tradition in Chile. It is, in fact, the oldest Communist Party in the entire region. It is very well established, very well institutionalized, and it has long-standing practices. However, it has undergone various changes throughout decades.

If we focus on the changes it experienced beginning with the run-up to the transition to democracy in 1989 and afterward, the Communist Party began to take a much more center-left position. It developed either direct or indirect alliances with what became the center-left governing coalition at the time, the Concertación. You might recall it was led by Michelle Bachelet and Eduardo Frei—some of the key leaders of that coalition. The Communist Party largely supported that center-left coalition, which brought us the kind of neoliberalism that has grown in Chile since those decades.

From that perspective, it would be difficult to call the current Communist Party a far-left party. It really is more of a center-left party. Indeed, if you look at some of the social contestation cycles that began in 2006 with the so-called Penguin Revolution—a social movement of high school students who were called penguins because they wore black-and-white, or dark-blue-and-white, uniforms—these young students were demanding better access to the educational system.

That movement started a cycle of contestation that lasted a few years and then transformed into something we will probably talk about a little later. But many of those early youth movements had a strong critique of the Communist Party precisely for being too timid, lacking imagination, and lacking democratic accountability. In many ways, the progressive cycle that began during that period had a strong critique of the Communist Party for not standing up strongly enough for various social rights.

So that’s the Communist Party; we shouldn’t think of it as a far-left party. Far from it. It can be very timid, and in some cases, even quite conservative in certain respects.

On the other hand, we have Kast and this coalition of right-wing groups and parties. And here, we can also fall into a problematic narrative, because when we say ultra-right-wing or hard right-wing, very quickly that evokes things like fascism or neo-fascism. But the right wing in Chile is actually quite forward-thinking, and has been so for a very long time. By this, I don’t mean progressive in any way, but forward-thinking in the sense that it has been able to successfully adapt to changing conditions on the ground, particularly given that Chile is one of the countries that has inserted itself into global cycles of capitalism, perhaps more so than many others in the region. So it is forward-thinking in that sense. It is willing to adapt, and it is quite pragmatic. It is willing to adjust to changing conditions that it cannot itself fully control.

Yes, they have a strong right-wing agenda on a number of topics that I’m sure we’ll talk about, and indeed many of the people who participate in this right-wing coalition probably have some ideas about Pinochet—nostalgia about Pinochet. In some cases, they even make public remarks supportive of people in the Pinochet regime. But in reality, pragmatism is their horizon—obviously with a right-wing tint to it.

You might recall that although Pinochet himself was a brute, a simpleton brute, the reality—and maybe precisely because he was that—is that he looked elsewhere for ideas. And where did he look for ideas? At the vanguard of American economic thinking at the time, which of course became Milton Friedman. And, this became the neoliberal project, which at the time was very marginal. So within the Pinochet story, there is also a story of looking outside and looking for new ideas to support a right-wing project.

I think this is the light in which we should see this right-wing coalition, rather than seeing it as nostalgic for some kind of European fascism or even Pinochet himself. That nostalgia is there, but it is counterposed with a strong sense of pragmatism.

The Rise of ‘Rule by Chaos’ in Chilean Politics

With José Antonio Kast receiving unified backing from libertarian, conservative, and ultra-right actors, do you see a consolidation of a “new right” coalition akin to the regional patterns you and Levy describe in the “Pink Tides, Right Turns” special issue?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: Yes, it is a consolidation of the right wing. The right wing will undoubtedly win the upcoming elections in December. The outcomes of the current elections were disastrous for the left, even though it maintained some control over the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. However, it’s truly a defeat for the left. If you think about the percentage of the vote that Jara received—approximately 24–25%, I think it was—and compare it to the number of people who voted to approve that progressive constitutional reform project, that was 38%. Only about 24% support Jara, and that’s a big decrease in that respect. It’s undoubted that this is a very difficult situation for the left, and that the right wing will be able to consolidate.

What is it consolidating? That’s the interesting question, and there are many concepts one can use to describe this new right wing. In fact, the very existence of so many of these different concepts—neoliberal authoritarianism, for example—shows that something is changing and has been changing for a long time. To throw yet another concept into the mix, one that I discuss in some of my work, there is the notion of an anti-bureaucratic authoritarian state. Many others could also be valid in terms of the discussions and debates.

But the key novelty in this right-wing coalition—and we’ve seen this with the case of Bolsonaro and Milei—is that it introduces, more than in other situations, the concept of rule by chaos. In the past, the right wing has been accustomed to ruling by pacifying subordinate classes and subordinate groups and repressing them. That will still happen under this new right wing, but it will now have a new dose of attempting to introduce chaos into the mix. That means actually activating the popular classes, activating subordinate sectors, manipulating them, and having them engage with politics, which is something different from what we have seen in the past.

How Mandatory Voting Backfired on Chile’s Left

How do compulsory voting rules—reintroduced in Chile—reshape the dynamics of right-wing populist mobilization, particularly among disaffected working-class male voters in the mining regions?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: Compulsory voting was introduced in 2022 for the final constitutional plebiscite. It turned out to be a big mistake. It surprised everybody, and most people attribute many of the reasons why the constitutional process was not successful to this compulsory voting. An interesting backstory here is that it’s hard to know who introduced it exactly. Some people will say it was actually Boric himself who introduced it, thinking they were in a strong position at the time and that introducing it would lead to a resounding success in the 2022 plebiscite. Others, depending on who you talk to, will tell you it was introduced by someone in the right wing as part of a negotiation with Boric, and that Boric went ahead with it naively, thinking it would work.

It absolutely turned out to work in favor of the right wing, because it forced people to vote on a document that had very little connection to the constitution process itself, about which they knew very little, and from which they were already quite alienated. Their instinct was to vote against it rather than in favor. And that dynamic will continue. Compulsory voting in the context of social media, and in the context of manipulation campaigns of all kinds, actually benefits the right wing in this case.

Crime, Migration, and the Limits of Progressive Narratives

Crime and immigration have eclipsed social rights and constitutional reform as the dominant electoral issues. What does this shift tell us about the vulnerabilities of post-neoliberal political projects in the face of moral panics and securitized narratives?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: It tells us about some of the challenges that progressive movements have had with these issues. If there’s a moral panic about immigration, the best the left has been able to do is cry xenophobia—which, of course, is right. But this kind of moralistic approach is not enough. There are other dimensions that need to be discussed and addressed by the left: psychological dimensions, emotional dimensions, and it’s not as easy as simply saying it’s just wrong. There has to be some other kind of response to that.

On the issue of crime, similarly, the typical answer to rising crime from the left has been to provide jobs, provide economic stability, provide support for citizens, and this will reduce crime. But in practice, this hasn’t necessarily panned out as one might expect. I looked at the case of Venezuela for a while—I still do—and at the height of some of the progressive tendencies in the Chavista project, you had the coincidence of lowering unemployment but higher crime. So you can have higher crime and lower unemployment at the same time, suggesting that there are other things going on beyond these simplistic narratives that the left sometimes uses. Not that that’s wrong—I strongly believe that if you provide a strong, supportive system that allows people to engage in work rather than criminal activity, that’s going to help. But, there are other things going on that the left must think about.

Why Kast’s Securitarian Agenda Isn’t a Return to Pinochet

Kast’s proposals—border walls, mass expulsions, militarization of public security—mirror global far-right repertoires. Do you interpret these as a populist securitarianism, or as an authoritarian neoliberalism in line with Pinochet-era legacies?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: Yes, there are legacies to Pinochet—undoubtedly, and we should be aware of them. But I think we would be mistaken to assume that the right wing is fundamentally nostalgic. Much of the new security-securitization proposals and projects they are advancing also contain an element of creating a new social terrain of chaos—injecting agitation into the population. Many of the things they propose will never actually be implemented, but simply articulating them, simply placing them in the public debate, generates an atmosphere of unrest. And that is precisely the atmosphere in which the right wing thrives.

What label to use—you can choose among several. But it is not a return to a classic authoritarian pattern. It is something different, and it’s important to understand the new terrain they are constructing. That terrain centers on how to concentrate power—how to exercise power—in a context of limited market competition at this particular moment in global capitalism, marked by the rise of extremely powerful monopolies at both global and national levels. They are trying to work out how to wield power under these conditions, and that is a novel context they are adapting to. They are shaping the conditions in which they can then operate with ease. That, I think, is their project.

Checks and Balances vs. Getting Mugged

How does Kast’s explicit admiration for Bukele’s carceral model fit into regional trends you have tracked regarding punitive or penal populism and the erosion of democratic checks and balances?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: At the popular level—and this is something I want to emphasize—the right wing is deeply attuned to everyday sentiments in a way the left simply isn’t. The right understands how people in poor and working-class communities are thinking. If you’re a working-class Chilean, or you have a precarious job, or you’re a low-income person, you’re already struggling to make a living, and you’re heavily indebted. That high level of indebtedness was actually introduced by the center-left, not the right; it was a center-left invention that expanded across broad sectors of the population.

So you’re in debt, you’re struggling to find stable work, your job is precarious, and on top of that, you’re getting mugged regularly in your own community. And what you hear from the center-left is: “we need democracy, checks and balances, human rights.” People think: “What good are checks and balances if I’m getting mugged? They feel, “I can do without all that if it means I’ll be safer.” The right wing is tapping directly into those feelings. Many people feel that under the center-left they didn’t gain much—and they’re still getting mugged. At least the right promises them they won’t.

There is a strong push by the right to activate and amplify those emotions. That’s the dynamic at play. Whether they will build prisons of the kind Bukele is constructing, I doubt it—but it’s possible. What matters far more is the growing resonance between right-wing discourse and popular sectors. That connection is very strong right now.

Democratic Backsliding Without Dictatorship: Chile’s New Risk

Given Kast’s Pinochetist lineage and the rehabilitation of authoritarian nostalgia among sections of the electorate, how serious is the risk of democratic backsliding if he wins the presidency?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: The issue of nostalgia—the right wing has elements of it, but it is actually far more forward-looking. It is the left that primarily lives in the space of nostalgia. As for democratic backsliding, I very much doubt that this will produce a classic authoritarian scenario. It is more likely to generate something novel—different—something that carries some of the flavors of past authoritarianism but operates on entirely different registers. And there are reasons for this. Chilean capital is among the most internationally and globally integrated in the region, and as a result, it has had to remain forward-looking. We need to understand the right wing in this light. The left is far more nostalgic—and unfortunately, that is a problem we still have not resolved.

After the Constitutional Defeat, the Left Has No Path to Hegemony

Jeannette Jara’s campaign reactivates a Communist Party tradition within Chilean democracy. From your research on grassroots movements and the limits of institutional leftism, do you see her as capable of reconstituting progressive hegemony—or is the left structurally weakened after the failed constitutional process?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: Unfortunately, there is no chance of her being able to reconstruct any kind of progressive hegemony. In fact, I see this election as the final nail—there have already been a few “final nails,” but this one truly feels definitive—in the coffin of a cycle of contestation that began in 2006. It continued in 2011 with the university student movements, out of which Gabriel Boric emerged, and eventually transformed into the creation of the Frente Amplio, a new coalition that for a brief period became a kind of hegemonic force. They then led a constitutional reform process that ultimately failed, for a number of interesting reasons we could discuss.

But the point is the opposite of what the question suggests: this moment does not mark the reconstitution of progressive hegemony—it marks the end of a long cycle that started many years ago. And if the best that progressive movements can offer at this point is a very mild center-left alternative to the right wing, then we are in serious trouble.

Why Chile’s Movements Struggle to Become Institutions

How does the collapse of the 2019–2022 constitutional movement resonate with your earlier work on the Chilean student movement (2011), particularly regarding the translation of contentious politics into institutional transformation?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: This is one of the great dilemmas of progressive movements: how to take the combative spirit and the innovations that emerge from social movements on the ground and translate them into effective political institutions capable of contesting government and leading change. This was the case in Chile during the student movement, and later as well. How to make that translation remains an open question. It has been a very difficult challenge in many contexts, and Chile is no exception. It points to the need to reimagine democracy in some way, and I think this is precisely where these movements struggle.

The right wing is very comfortable with the way it operates, with very strict hierarchies. Progressive movements are not. They try to reinvent how to engage with each other in democratic ways, but this is often messy, and many mistakes are made along the way. The Chilean student movements certainly experimented with different kinds of democracy. There were some really interesting experiences with public neighborhood meetings in the run-up to the 2019 movement—people coming together in public parks to discuss politics and engage in new democratic practices.

But moving from those experiments to establishing similar logics within larger parties is very difficult. It has proven extremely challenging. This is where the left needs to focus specifically. And there is some good news in the failure of this long cycle of contestation: it allows us to see more clearly than before that we need to focus on understanding the relationship between leaders and followers. Progressive movements have a strong discomfort with these questions. We like to imagine that everyone can be a leader, and sometimes that is simply not possible. Who should lead? What makes a good leader—and just as importantly, what makes a good follower—are questions we need to discuss more openly in the context of translating social movements into political institutions.

Chile’s Election Marks the End of the Pink Tide Illusion

In your view, does this election signify the exhaustion of the second-generation Pink Tide, or merely a recalibration within a longer regional cycle punctuated by commodity dependence, political volatility, and institutional fragility?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: It is true that there has been a kind of renaissance of different left political projects in the region that have come to power—Colombia for a moment, and also Peru. Many people began to see these developments as a sort of second coming of the Pink Tide. But we need to be careful with this. There have been some interesting experiments within some of these governments, but the context in which they emerged is completely different from that of the original Pink Tide, which began back in the late 1990s.

The circumstances now are entirely different: we are looking at economic volatility, economic crisis, and a highly fragmented left. This is simply not a context that allows any kind of strong, progressive wave—a Pink Tide 2.0—to sustain itself for very long. So that’s the first point. I really don’t see this second Pink Tide as being anywhere near as substantial as the first one. In that sense, what is happening in Chile right now feels like yet another final nail in the coffin of the idea that a second Pink Tide is emerging. We should not think of it as analogous to the first one.

Disinformation as a Tool of Chile’s New Right

How do you assess the role of corporate media and disinformation ecosystems—topics raised in the Pink Tide literature—in shaping anti-progressive sentiment and facilitating the rightward shift in Chilean public opinion?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: Social media has been a very fertile terrain for the right wing, which has moved into that terrain very quickly and very enthusiastically. It has hired an army of trolls to influence public opinion, and they are very effective at it. They have done a really impressive job of targeting some of the weaknesses of left or progressive discourses and planting doubt in large swaths of the population about what it means to support the rights of citizens. Basic things are coming into question for the very first time precisely because of how effective they have been in the realm of social media.

In particular, they have been good at creating a narrative—the narrative of fascist versus communist—which really works in their favor. People on the left are too defensive about this topic, and people can see it. And when people see that kind of defensiveness, they sense that something is wrong. The right wing has been very effective at pushing those triggers within progressive sectors that reveal to the broader population that they are not fully comfortable with some of the things they are saying.

And this has been the job of the right wing: to seed doubt, to plant doubt, to create an atmosphere of general misinformation and chaos—communicational chaos and informational chaos—in which they can then operate with much ease.

Why Chile’s Left Can’t Bridge Streets and Institutions

Considering your argument that participatory and prefigurative movements often produce tensions with state-centric left governments, does the recent election reflect unresolved contradictions between movement-based radicalism and party-led governance?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: No doubt—and it clearly reflects deep contradictions. It’s striking to think about the movements born in 2006 and 2011, out of which emerged the demand for constitutional reform, and how difficult it was to translate that demand into practice—to convince large parts of the Chilean population that changing the Constitution was necessary. This is why it was such a shock that only about 38% of people voted in favor of the new draft.

This outcome reflects many of the tensions between formal politics and street politics, or extra-parliamentary politics. It is very difficult to bridge these spheres, and we haven’t really built the kinds of organizations capable of making that translation possible. This remains an ongoing task for progressive movements.

In particular, the process exposed lost capacities in the realm of popular education. It is one thing to demand or imagine a very different constitution—as was the case in Chile. Social movements carry what they call “horizons of change”: visions of an alternative society they hope to realize. Sometimes these horizons are explicit, sometimes implicit, but they are always there.

The challenge arises when these horizons of change drift too far from the movements’ capacity to engage in popular education and materially advance those visions. That gap inevitably creates problems. And from my perspective, the real motor of this entire process is the question: can progressive movements carry out effective popular education? This is especially difficult today, when people are tied to their phones and immersed in social media debates rather than substantive collective discussions in other forums.

So the major challenge for progressive movements now is how to engage in popular education in a way that narrows thisgap. In Chile, the gap grew so wide by 2022 that people simply stopped believing in the project of constitutional change.

A New Right-Wing Axis—and Its Democratic Costs

Kast’s openly pro-Trump positioning aligns Chile with an emergent right-wing axis in Argentina, Ecuador, Bolivia, and potentially Colombia and Peru. How does this recomposition of hemispheric alliances affect prospects for democratic deepening and autonomous development in the region?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: This is definitely a new right-wing alliance—a regional alliance—that is emerging. Democracy will take a toll, without a doubt. What they are trying to do is not destroy democracy; they are trying to reinvent it—something the left should be doing but has struggled to do. And they are succeeding. They are actively reinventing democracy, and it’s working.

Of course, there are elements that recall past authoritarianism; those elements are there. But, as I mentioned earlier, there are also strong elements of novelty. This is a Bolsonaro–Milei political playbook, though not as intense in Chile. Chile has a much more conservative, even stoic political culture compared to those countries. So you won’t see the more outlandish shenanigans of figures like Milei or Bolsonaro, but you will see a small taste of that in Chile—perhaps for the first time.

Indeed, they are consolidating into what I think is an experiment in how to exercise power in a context marked by very strong global monopolies, limited market competition, and a totally fragmented left. For that, you don’t need a dictatorship. You need something different—and that is what they are trying to figure out. It’s not good, but it’s also not a return to the Pinochet era.

Democratic Resilience Beneath the Surface

And finally, Professor Larrabure, what scenarios do you foresee for Chile’s medium-term political trajectory—particularly regarding (a) democratic resilience, (b) the future of the constitutional question, and (c) the ability of social movements to intervene in an increasingly securitized, polarized political field?

Assoc. Prof. Manuel Larrabure: The constitutional question is over. I don’t think that’s on the table anymore. The question of social movements intervening in the political terrain—yes, they’ll intervene. There’s no doubt there will be responses from social movements throughout this period of the new right that’s emerging in the country. That’s been the case in Latin America for a very long time; movements do respond to these kinds of attacks. The question is, how are they going to respond exactly? What new repertoires are they going to use? Are they going to learn some of the lessons of the previous cycle of contestation, or are they simply going to repeat what they did? And I think this is a very important question.

Is this going to lead to challenges to democracy as we know it? Yes, it will. But Latin America has a strong record of democratic resilience; democratic movements are always there, just beneath the surface. And I don’t doubt for a second that they will respond. I hope that through that process—and no doubt a new wave of contestation will begin at some point—they can articulate progressive politics, a political transformation, a social transformation that is more effective and able to learn from the mistakes of the past.