In this incisive ECPS interview, Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher, Associate Professor at the University of Calgary, explores how populism is reshaping US foreign policy—from tariffs as symbolic resistance to institutional erosion under Trump 2.0. Arguing that “Trump is not the cause but a symptom,” Dr. Boucher warns that even without Trump, populist forces will endure, backed by media ecosystems, think tanks, and loyalist networks. He emphasizes that “this is not really an economic argument. It’s a political and populist argument,” driving a shift from multilateralism to nationalist retrenchment. A must-read for anyone interested in the ideological drivers behind today’s turbulent geopolitics.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In this timely and penetrating interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher—Associate Professor at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy and Department of Political Science—offers a comprehensive assessment of how populist ideology is transforming American foreign policy, institutional norms, and multilateral engagement. Central to Dr. Boucher’s argument is a provocative but sobering claim: “Trump is not the cause but a symptom.” Even if Donald Trump were no longer on the political stage, Dr. Boucher insists, “this movement would remain part of the political conversation,” underscoring the durability and depth of populist forces within American society and institutions.

Dr. Boucher advances the ideational approach to populism, which links belief systems to behavioral patterns. Rather than viewing populist discourse as purely performative or strategic, he argues that “these people really believe in these values and these hierarchies of beliefs, and they’ll start to act upon it.” This perspective, he contends, helps explain the internal coherence of Trump’s policies across domains, including trade, immigration, and foreign relations.

One of the interview’s central themes is the symbolic repurposing of trade tools like tariffs. For Trump and his supporters, tariffs are no longer just economic instruments; they are reimagined as expressions of national sovereignty and resistance against a “globalist elite.” As Dr. Boucher puts it, “this is not really an economic argument. It’s a political and populist argument.” This reframing speaks to broader populist tendencies that elevate identity, emotion, and anti-elite resentment over technocratic expertise and institutional procedure.

Throughout the conversation, Dr. Boucher traces how institutional degradation—accelerated under what he calls “Trump 2.0”—is being enabled by a growing ecosystem of populist actors, from think tanks like those behind Project 2025 to social media influencers and tech elites. He warns that foreign policy institutions like the State Department and Department of Defense are being hollowed out, potentially making way for a more centralized, nativist, and unilateralist foreign policy doctrine.

Ultimately, Dr. Boucher’s analysis is a call to recognize the structural, not merely electoral, nature of the populist threat. “There’s significant support for it,” he reminds us. Understanding this dynamic is essential for those hoping to defend democratic institutions and multilateralism in an era of resurgent populism.

Here is the lightly edited transcript of the interview with Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher.

They Don’t Just Talk Like Populists—They Behave Like Populists

Professor Boucher, thank you so very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question. How does the ideational approach to populism help us understand the continuity between Trump’s first and second administrations in shaping foreign policy through anti-elitist and pro-people rhetoric?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: That’s a great question, as it delves into a central debate in populism studies: the distinction between the discursive and ideational approaches. What I appreciate about the ideational approach is its emphasis on the connection between beliefs, values, and behaviors. This perspective posits that populist leaders and their supporters don’t merely articulate anti-elitist and pro-people sentiments—they genuinely hold these beliefs and act accordingly. Thus, when viewed through the ideational lens, populism is seen not just as rhetoric but as a guiding ideology that influences actions across various domains. This framework helps explain the consistency in populist behavior, as individuals internalize these values and implement them in practice.

And this is why I really like the ideational approach to foreign policy—because the argument is that Trump not only holds a thin-centered populist ideology, but also implemented policies aimed at realizing these ideas, targeting elites and advancing pro-people narratives. This approach influenced not only domestic politics but extended into foreign policy as well. When using a discursive approach, it’s harder to explain why a populist would shift across different policy sectors. But if they have an ideology, the assumption is that this belief system extends across various domains—economics, immigration, and, in this case, foreign policy. So, I really believe the ideational approach helps us better understand the consistency in the Trump Administration’s policies.

In foreign policy, for example, the first Trump administration made several decisions closely tied to populist views. There was a strong emphasis on tariffs, as well as on immigration—remember the travel ban and the push for anti-Muslim policies. These moves clearly reflected a blend of populism and ethnonationalism at the core of the administration’s agenda. And we’re seeing similar patterns emerging again in Trump 2.0. I think that’s important to understand.

You’ve written about populism’s impact on foreign policy coherence. In the current environment, can foreign policy institutions remain resilient under populist leadership, or do they inevitably erode?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: When you sent me that question, I really thought about it, and I’m still kind of debating it in my head. I think there’s a lot of interesting research about populism on how populist leaders go after institutions and try to change or disaggregate them so that a lot of the power centers shift back toward the populist leaders and away from these institutions. In foreign policy, we’re seeing the same thing, especially in Trump 2.0.

In the first Trump administration, foreign policy institutions—the State Department, the Department of Defense, even the Department of Homeland Security—were more or less able to maintain their integrity. A lot of the so-called “adults in the room” at the time came from the national security and foreign policy environment.

But when we look at Project 2025, a lot of the post-Trump reflections suggest that one of the administration’s misgivings about the first term was that these institutions resisted Trump’s agenda. In Trump 2.0, a major focus is on restructuring these institutions—the State Department, the Department of Defense, Homeland Security, even the NSA. There’s a strong push against the elites and a shift toward loyalists.

At the international level, Trump is doing the same thing: pulling the US out of the WHO, expressing skepticism about the G20 and G7, and generally trying to undermine international institutions that might constrain his foreign policy decisions.

What I find interesting is that Trump uses the same kind of discourse to justify what he’s doing domestically and internationally. He talks about elites controlling institutions, about those institutions not representing the will of the people, and about the need to undo them so that the people’s voice is heard. And you see the same thing at the international level, where he argues that globalists and internationalists are controlling those institutions. That’s why, he claims, the United States has to put Americans—the American people—first and, in doing so, take back control from those institutions that influence foreign policy.

Extending the Manichean Divide: From Domestic Elites to Global Conspiracies

How has the Trump administration weaponized populist narratives that portray global trade regimes as elite conspiracies to justify protectionism?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: This is a question I’m asking myself all the time. I think it really— from an ideational perspective—it’s not just about weaponization. My question always, in my head, is whether populists really believe what they say, or is it just kind of a way to frame their issues? And if you take an ideational approach, you’ll say these populists actually believe that that’s true.

Trump has been very consistent across his career in thinking that tariffs are a good way and a good policy, and much of the argument was that outside actors and the elites were essentially taking over American policies and abusing the American people unfairly. It’s about transposing this kind of anti-elite argument from the domestic environment onto the international level, and saying: “All of these countries in the world and all of these globalists are creating this network that’s abusive to the United States,” and that somehow they have removed the capacity of Americans to make their own policies and decide for themselves—that the American people have lost agency.

Trump really used this kind of language to articulate a protectionist policy that frames outside actors as abusive and corrupt institutions, countries, and people—and that he, as the populist leader, is fighting back and reclaiming these powers for the American people.

So the way I see it, you essentially extend the Manichean view of populism to the international level, where “the people” becomes the American people and “the elites” are reimagined as foreign actors or global institutions seen as corrupt and exploitative. It’s the same framework of a divided world: the corrupt versus the pure people, who are portrayed as disenfranchised and disempowered by those elites.

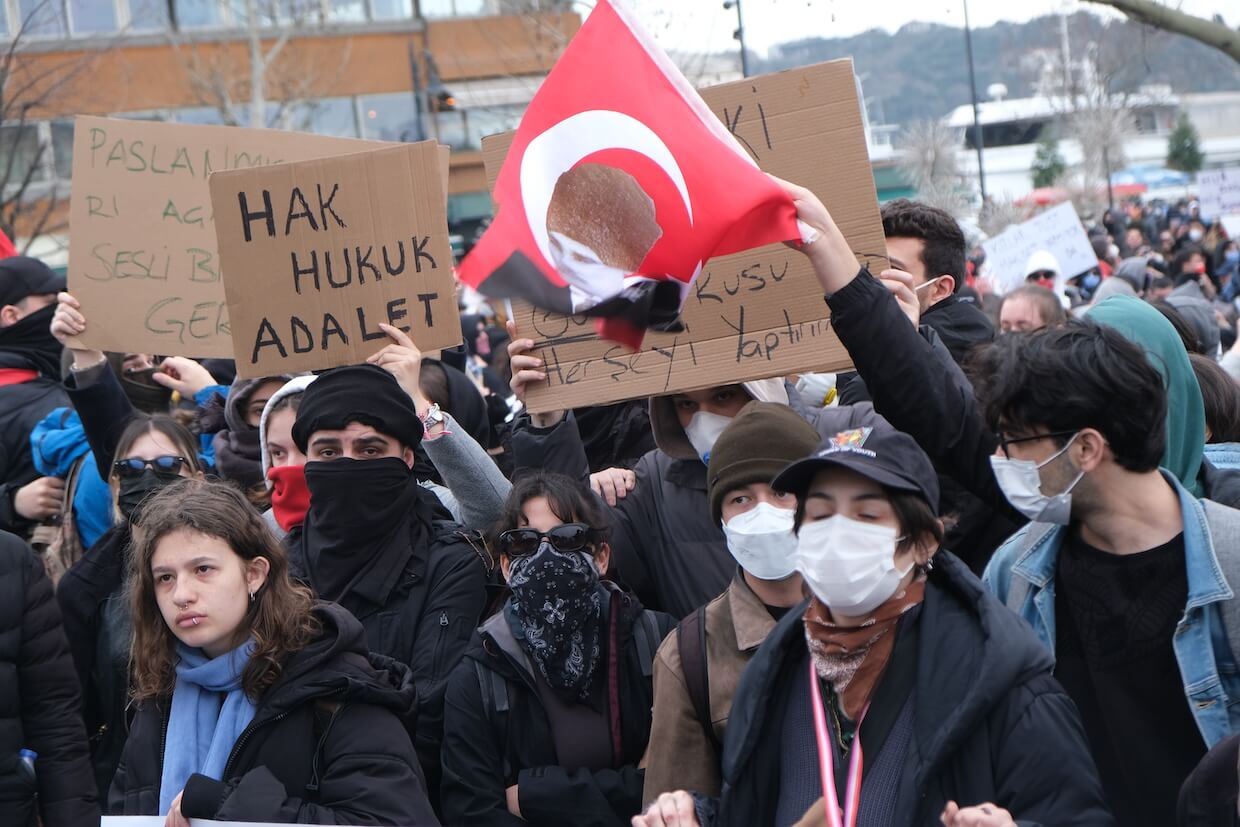

Your chapter in a recently published book highlights the role of nativist securitization in justifying the travel ban. In today’s context, how might similar nativist framing be deployed in foreign policy debates such as immigration from conflict zones or relations with ‘globalist’ institutions?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: The paper was written a long time ago, and it’s ironic that it took so long to get published—only for the same kinds of nativist and anti-immigration policies to reemerge. It’s depressing to realize that, in a grim way, we were right. The argument in that paper was that, on immigration issues, ethno-nationalism and populism were structured similarly, creating a framework of outside and inside actors—an idea central to ethno-nationalist thinking.

I thought at the time that it was an interesting way to frame those issues in the populist context. Others have worked extensively on populism, far-right populism, and ethno-nationalism. In this context, what we saw was that Trump’s framing of immigration issues was really centered around the narrative of elites versus the people—with “the people” portrayed as a kind of ethno-nationalist, pure group—and this created an outside/inside actor dynamic. That framing was central to the policy and shaped much of how these issues were understood. That’s how we approached the argument.

Trump Is the Symptom of a Deeper Foreign Policy Shift

In the light of the increasing overlap between populism and foreign policy, do you foresee a lasting structural transformation of US foreign policy priorities—away from multilateralism and toward identity-driven narratives of national sovereignty and civilizational conflict?

Jean-Christophe Boucher: I do. I think so. I’m a Canadian, and of course, we’re very close to the Americans. We’ve been witnessing a lot of what’s happening—and as you know, we’re bearing the brunt of much of the United States’ abuse at this time: being called the 51st state and facing challenges to our sovereignty.

What we see from our perspective—and I think this applies to the populist perspective as well—is twofold. On the one hand, we sometimes mistake the leader for the movement. We tend to think that Trump, the populist leader, is the architect of everything. That’s a mistake. What we’re seeing among the American people right now is a real appetite for populist discourse at the grassroots level—at the demand level—and Trump is merely an embodiment of that pressure. Many individuals within American institutions and among the elite also hold populist ideas. Even if Trump were to disappear from the scene, the movement would remain part of the political conversation, and I don’t think it would fundamentally change what’s happening in the US. Trump is not the cause but a symptom. There’s a broader movement that supports the way he behaves, which helps explain why the pushback against his undermining of institutions hasn’t been as strong as one might expect—because there’s significant support for it.

The second part is that systematically, the Trump administration is going after the foreign policy establishments and institutions in the US—State Department, DoD, DHS. At all levels, there’s been a deep dive into these institutions and an uprooting of many programs and checks and balances that had been in place. It’s not just USAID. If you look at what the Department of Defense is doing on DEI and other issues, there’s a deep restructuring underway. So even if Trump moves away in 2028, those institutions will look very different from when he came in. It will take time to rebuild them—if that even happens.

Not only is there an appetite for what Trump represents, but the institutions that once safeguarded against that appetite may no longer exist. We’ll be left with institutions that make it easier for a populist leader to pursue a foreign policy that is more self-centered, more nativist, and more protectionist. And I think that’s the future we’re likely to see in the coming years.

Social Media Lets Populist Leaders Sidestep Institutions and Speak Unfiltered

Given your findings on the use of social media to propagate populist foreign policy, how do you assess the evolution of this communication strategy in Trump’s second term, especially with shifting media platforms and increasing polarization?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: I think it’s part of the argument. There’s a lot of good research on why populist leaders prefer social media or alternative media as a way to communicate with the people. There are a lot of arguments. One is that mainstream media are portrayed as those of the elites, and somehow populist leaders have a deep-seated obsession about that. But social media also allows the populist leader to have a direct connection with the people and talk to them specifically.

If you look at what the Trump administration is doing, there’s a lot of that. In Trump 1.0, there were all these attacks on mainstream media, on fake news, and all of those were constant. We see it in our data on tariffs, but even on nativism—a lot of the anti-elite discourse coming directly from Trump and from the people is directed against those media institutions that seem to represent the elites.

What I find interesting right now in Trump 2.0 is that Trump is actually going after those institutions directly. You’ve seen, for example, how they’re suing CBS and other institutions, cutting ties with NPR, and really going after a lot of the power centers of mainstream media.

You also see how he’s allowing a lot of alternative media to attend press conferences, giving those outlets a larger impact.

Finally, we see that the Trump administration—like Trump 1.0—really communicates many of its ideas and arguments on social media. On tariffs, for example, policy officials actually learn about new directions in tariff policy through Trump’s posts on Truth Social or X. Social media becomes a really strong way for him to do this.

It also allows the populist leader to sidestep all the checks and balances of institutions—but also internally—where what he can say and how he addresses himself is unrestrained by those actors. And that really makes it an important part of that conversation.

Trump Is No Longer Alone—Populism Now Operates as an Institutionalized Ecosystem

You demonstrate that populist narratives were reinforced by networks of actors beyond political elites, including media and think tanks. How do you see these networks evolving under renewed populist leadership, and what new actors have emerged in this space since 2017?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: This is one of the things we wanted to highlight. The more I reflect on how we wrote about those issues at the time, the more I realize that our central argument was this: much of the literature focuses on populist leaders but overlooks the broader network that supports them. In fact, if you’re trying to understand a populist movement, you have to consider all the actors who enable and sustain the leader. It’s very difficult for a populist leader to operate in isolation—there’s always a constellation of other actors involved.

When we looked at social media networks and influencers, we found that while the populist leader was the most influential figure, there were many other groups—advocacy groups, think tanks—that supported the environment around him.

Today, you see exactly the same thing. Some of those actors are now part of the Trump administration. For example, Project 2025, which was at the center of a think-tank effort to produce populist ideas on transforming government in a potential Trump 2.0 administration, is now embedded in the administration. Figures like Elon Musk and the tech bros, who pushed populist ideas on social media, were essential to Trump’s reelection and are now part of the governing sphere, helping implement the president’s agenda.

People like Jack Posobiec and other far-right network figures who were once just part of the ecosystem around Trump and the MAGA movement are now in or close to government. So, when we think about the Trump administration, we should stop thinking of Trump as the sole actor—there’s an entire ecosystem that was nascent in Trump 1.0 but is now fully institutionalized in Trump 2.0.

What I saw in 2016–17 was a loose, informal network. Over the last four years, that network has crystallized into a proper movement—with influencers, money, institutions, and architecture that now serve as the base of the MAGA movement. It’s a lot more formalized.

That’s why the Trump administration is now able to move faster on its agenda and more effectively push its populist ideas into the system—because of the support from all these actors. He wouldn’t be able to do what he’s doing without Elon Musk and others backing him. He wouldn’t be able to move without Mike Johnson controlling Congress. Many of those actors who were loosely connected in 2016–2020 are now firmly part of his circle, accelerating and deepening the reach of his agenda into institutions.

How have Trump’s populist politics redefined the symbolic value of tariffs—not merely as economic tools, but as performative instruments of sovereignty and resistance against the ‘globalist elite’?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: This is where the populist argument comes in—where you mix the economics of it with the politics and belief system behind it. In the US right now, in the conversation around tariffs, there are really two conversations happening at the same time. You have the economic conversation, where a lot of economists are trying to explain why tariffs are a good thing for the US and trying to justify them. I’m less interested in that, because it seems like all the data goes against that argument. The idea that tariffs are economically beneficial is a marginal one.

What I find more interesting and more conducive to explaining what’s happening is this belief system. Trump genuinely believes that tariffs will undo the power of the elites and recreate a structure of economics that refocuses on the good of the American people. And somehow, that’s how it should be. The interesting part is, you can hear it when he talks—he recognizes that this will have deep economic impacts. He says, “This will be difficult. This will produce pain. But this is a good thing for the American people.” We’re going to bring back real jobs for real Americans—for workers—and that matters more.

Despite the economic pain, this is not really an economic argument. It’s a political and populist argument that explains why he supports tariffs. And when you listen to his political rationale, it makes a lot more sense than if you approach it purely from an economic perspective. I also think that’s why trying to argue with the Trump movement on economic terms doesn’t work—because in their view, it’s not an economic argument at all. It’s a political belief system they’re trying to put in place. They really don’t care if some economic pain is produced in that process. What they’re seeking is to re-center economic power around the American people, and not around what they see as the elites and people in the cities who benefit from a global international system.

Tariffs Are Populist Symbols of Sovereignty and Struggle

You argue that foreign policy is increasingly shaped by emotional and identity-based appeals. To what extent do you see populist trade wars as cultural projects, not just economic or strategic ones? Are we now seeing what you anticipated: the normalization of tariffs as political theatre, rather than as policy tools grounded in economic rationale?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: Remember that we wrote this paper in 2017–2018—it was a long time ago. What really concerns me is that I was hoping we would be wrong, or that it would turn out to be just a passing moment. But today, it’s becoming more and more about exactly that—and it’s not just within the Trump administration. We’re seeing increasing arguments that trade and protectionism are being framed as formal expressions of the will of the people. I think that’s the important part.

One of the arguments we see in the populist movement is that global trade networks really removed the center of power from the people to these elites—the bankers, the traders—who were able to control global markets, while the people were left behind. And, of course, they characterize these people—these Davos and World Economic Forum elites—as corrupt actors controlling the international economic system.

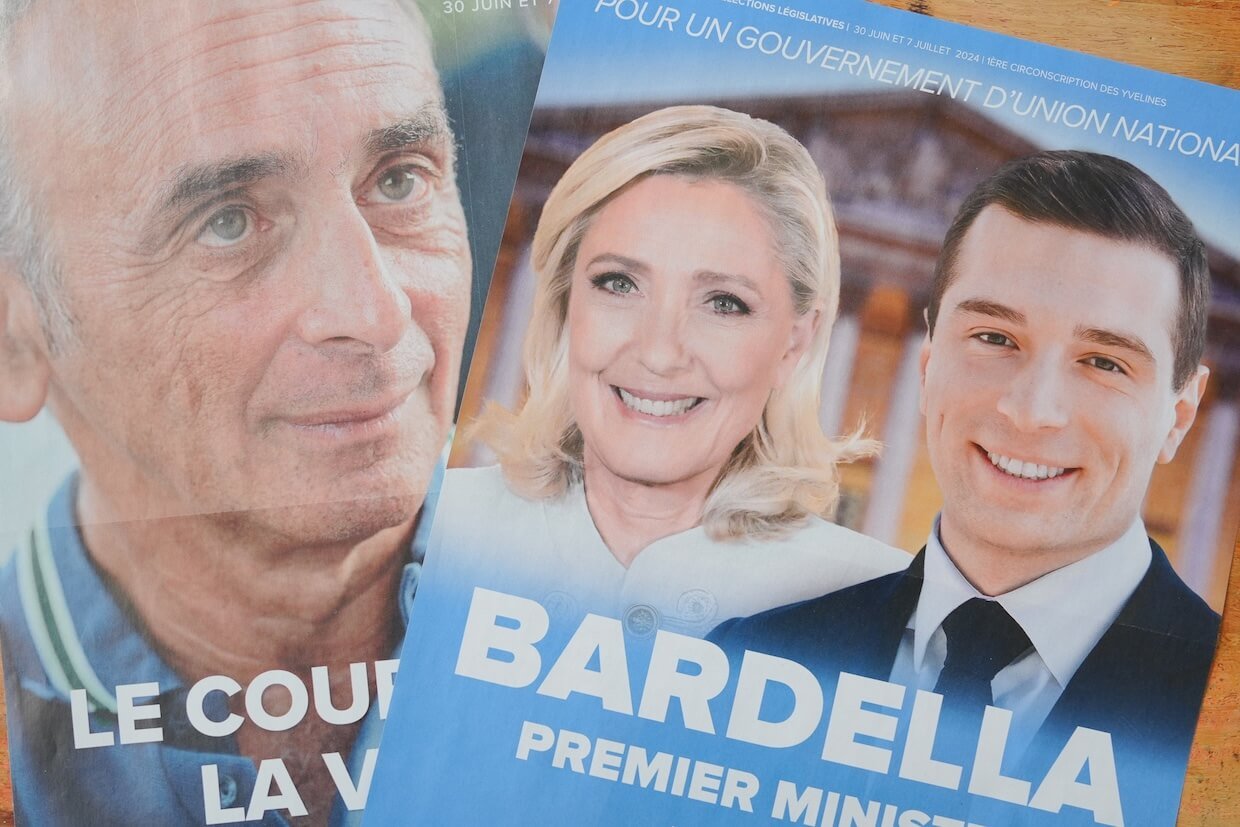

What I find interesting—and this is why I think it’s an ideology more than just a discourse—is that most populist leaders, from the left and the right, have the same rhetoric. From Marine Le Pen in France to Nigel Farage in the UK to Orban in Hungary, you’re seeing the same kind of argument: that we have to take power away from the globalists, create protectionist policies to protect the people, and disengage from these global economic networks.

I believe that right now we are in that phase. We’re seeing a retrenchment from global politics and a refocusing on national manufacturing and supply-side arguments. Trade will become more sticky, and there will be more friction in international trade than we were used to.

What I find interesting—last point—is that even without Trump, when we listen to the Biden administration, there’s a lot of talk about supply chain management, supply chain security, and bringing back manufacturing jobs and national economic capacities. So even without Trump, you still have this kind of retrenchment from loose international trade and a renewed focus on domestic politics and domestic economics.

Tariffs Aren’t Just Economic Tools—They’re Instruments to Recenter Power on ‘the People

Drawing on your “I, Tariff Man” analysis, how has Trump’s second term intensified the personalization and performative use of trade policy? In what ways does this reflect broader populist tendencies that reject institutional expertise and multilateralism while mobilizing domestic political support?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: From an ideational perspective, populism—and its Manichean view of the world—shapes how people think and behave. In the trade environment, we see this clearly: tariffs become a tool for constructing a populist framework. Through tariffs, institutions built to manage global trade are effectively weakened or disassembled. Power is taken away from the elites who control international networks and redirected toward “the people,” refocusing economic forces inward.

In the populist literature, there’s always this argument—whether populism is a disease of democratic systems or a correction to a lack of representation in an economic system. And I really think the way a lot of populists think about tariffs reflects the latter. It’s seen as a corrective to brittle trade negotiations that took economic power away from the people and handed it to elites—people in cities, in the service industry, who were able to live well while workers became less powerful. So, retaking that power becomes the goal.

I don’t think it’s just performative. I think they genuinely believe this will recenter power on the people and help recreate a manufacturing base. When you listen to how some economists frame it, they suggest it will make life harder for service industries in cities, reduce their economic influence, and shift that power toward manufacturing and “Middle America,” where more of the population resides. Personally, I don’t think it will work that way—automation and other structural factors have played a major role in the erosion of US manufacturing—but from their perspective, the argument is clear: jobs were exported, elites benefited, and the people suffered. Tariffs are intended to sever those global networks and refocus the economy internally.

It might result in a less productive America. It might hollow out the cities and the service economy. But for populists, that’s probably the point—and they’re okay with that.

We’re Heading Toward a Smaller, Less Open World

With Trump’s renewed disengagement from WTO norms, do you see this as a terminal moment for the postwar liberal trade order, or is there still a path to restoration? What lessons can be drawn from the Trump era about the vulnerability of international economic governance to populist subversion, and what reforms are needed to future-proof institutions like the WTO from nationalist retrenchment?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: As a Canadian, I think about this all the time—and to be honest, there’s a lot to consider.My first assumption is that the Trump administration is just a symptom. So you’re still going to see a broader retrenchment from free trade, and even if, say, in 2028, a new president were elected, I don’t think this kind of protectionism would simply go away. A lot of international institutions will have a hard time surviving in that kind of system.

What I’m seeing, at least from Canada’s perspective, is that maybe some countries will keep these institutions alive and reduce the dominance of large multinational corporations. My sense is that the future lies in minilateralism—where like-minded countries who still see value in trade will maintain these institutions, but more for their own benefit than for the global system.

At the EU level, I think we’ll see more internal consolidation of trade and governance policies—unless, of course, a far-right government comes to power in a major state like France, which could unravel key aspects of the EU. Countries like Canada still want more trade and strong relationships with institutions like the WTO, but I believe the global trade environment will be significantly smaller than it once was.

Governments like ours can’t replace the United States in terms of global leadership—our prime minister recently said “if the Americans won’t lead, Canada will,” but let’s be honest: no one can replace the US in terms of resources and influence. What we might see is more involvement from China, Russia, and Iran in shaping these institutions—but their vision for the international system is quite different from that of the US and its allies.

So, my assumption is that we’re entering a deeply transformative period. The world will become smaller, more fragmented into blocs of countries defending their own values and interests—and far less open at the international level.

In the end, I think the countries that will suffer most are those in Africa, Latin America, and other regions of the Global South, because they benefited significantly from openness and multilateral institutions. Wealthier nations can still provide many of the services and information gathering that multilateral institutions once offered, but smaller states can’t. If you were a small country in Africa, those institutions were a lifeline.

I guess I’m a pessimist here, but I do believe we’re heading toward a smaller, less open world.

Multilateralism Is No Longer a Principle—It’s a Strategy

And lastly, Professor Boucher, how should policymakers in Canada respond to the dual threat of economic harm and normative erosion posed by populist-driven trade wars? What counter-narratives can be mobilized to restore public trust in multilateralism?

Dr. Jean-Christophe Boucher: Even in Canada, I’d say that—let’s put it this way—there was a movement not that long ago, when I was doing my PhD, that argued multilateralism was more of a practice than a belief. The idea was that what was good was not multilateralism as an end in itself, but as a means—a mode of engagement. The work in practice theory and international relations emphasized that what mattered was the activity of multilateralism, rather than its outcomes.

I don’t think that holds anymore, even in Canada. I think Canadians are now less and less devoted to multilateralism as a principle, and more interested in promoting their own views and strategic interests. What we see here is a sense that the world is retrenching, becoming smaller, and that we need to refocus our attention more narrowly.

The rise of China and Russia has shown how difficult it is for multilateral institutions to adapt. Now that the United States has also joined this retrenchment, I think it signals that those institutions won’t survive in their present form. As a result, a lot of Canada’s foreign policy is moving away from traditional multilateralism and toward more bilateral or minilateral relationships.

For example, if you look at what Canada is doing: we’re deepening ties with key European partners—not just through Brussels, but also through Paris, London, and Berlin. There’s been increasing talk about Canada joining the European Union, and frankly, if there were a referendum today, it might actually pass. Many Canadians feel that makes sense strategically.

Recently, we also published a document formalizing our Indo-Pacific strategy. If you look at where Canada is focusing its efforts, it’s clearly on strengthening relationships with partners in the Pacific—Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Australia. There’s a renewed emphasis on ASEAN as well.

So we’re moving away from the big, universalist international institutions and focusing more on regional, minilateral partnerships. It’s just easier. The commitment to shared values is clearer, and the conversations are more straightforward than what we often encounter at the global level.