In an interview with the ECPS, Dr. Taro Tsuda of Meiji University argues that Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s landslide victory and supermajority mandate signify continuity within Japan’s dominant-party system rather than a populist break. Despite her historic status as Japan’s first female prime minister and her “diligent and tough-speaking” leadership style, Dr. Tsuda stresses that her agenda and career remain rooted in the Liberal Democratic Party’s mainstream. He interprets her electoral success as part of the LDP’s strategy to reclaim drifting conservative voters and preempt challenger movements, with Takaichi herself becoming the party’s central electoral asset. Her rise, he concludes, demonstrates how leadership personalization and institutional resilience can reinforce—rather than disrupt—established structures of governance.

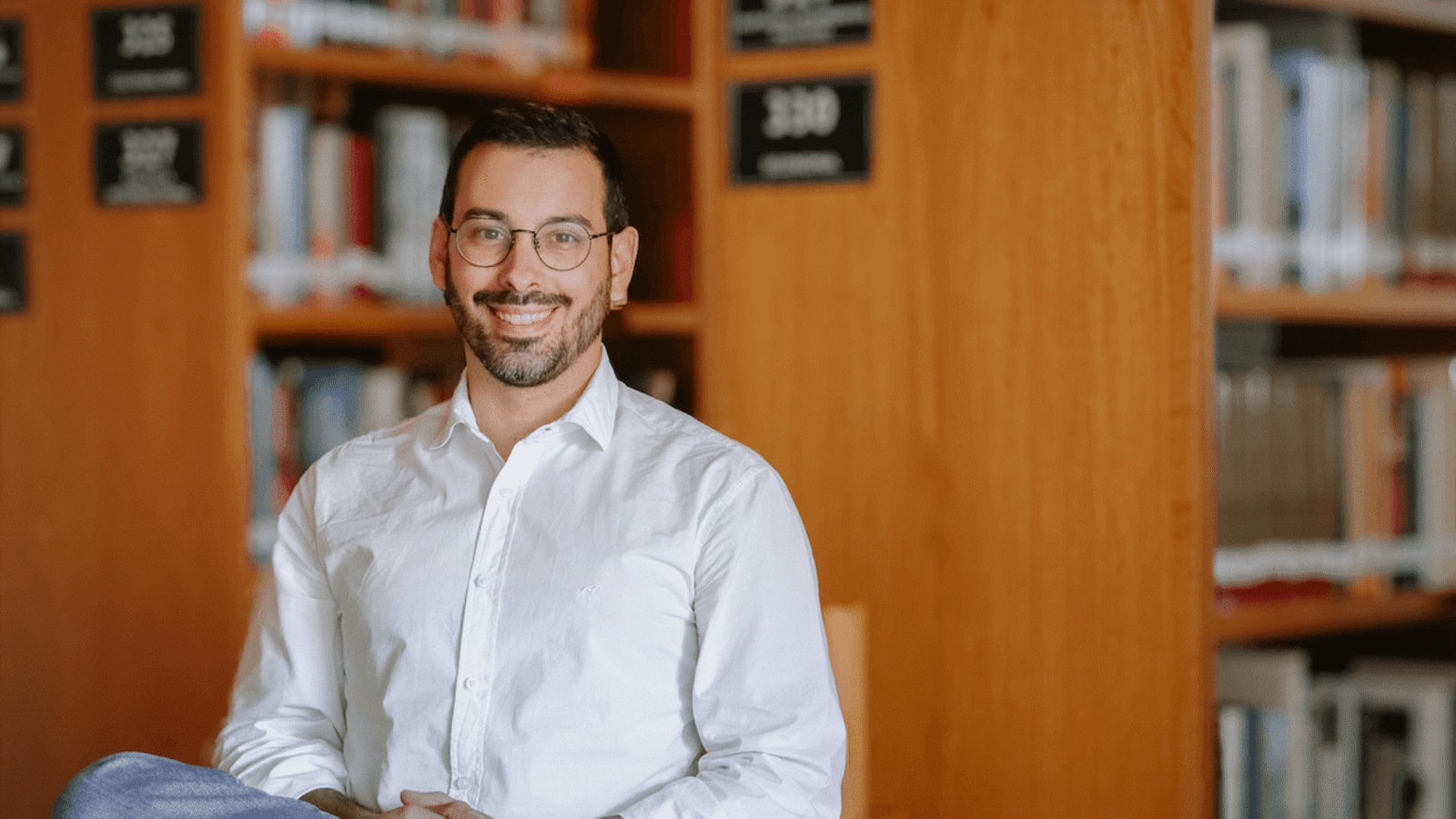

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

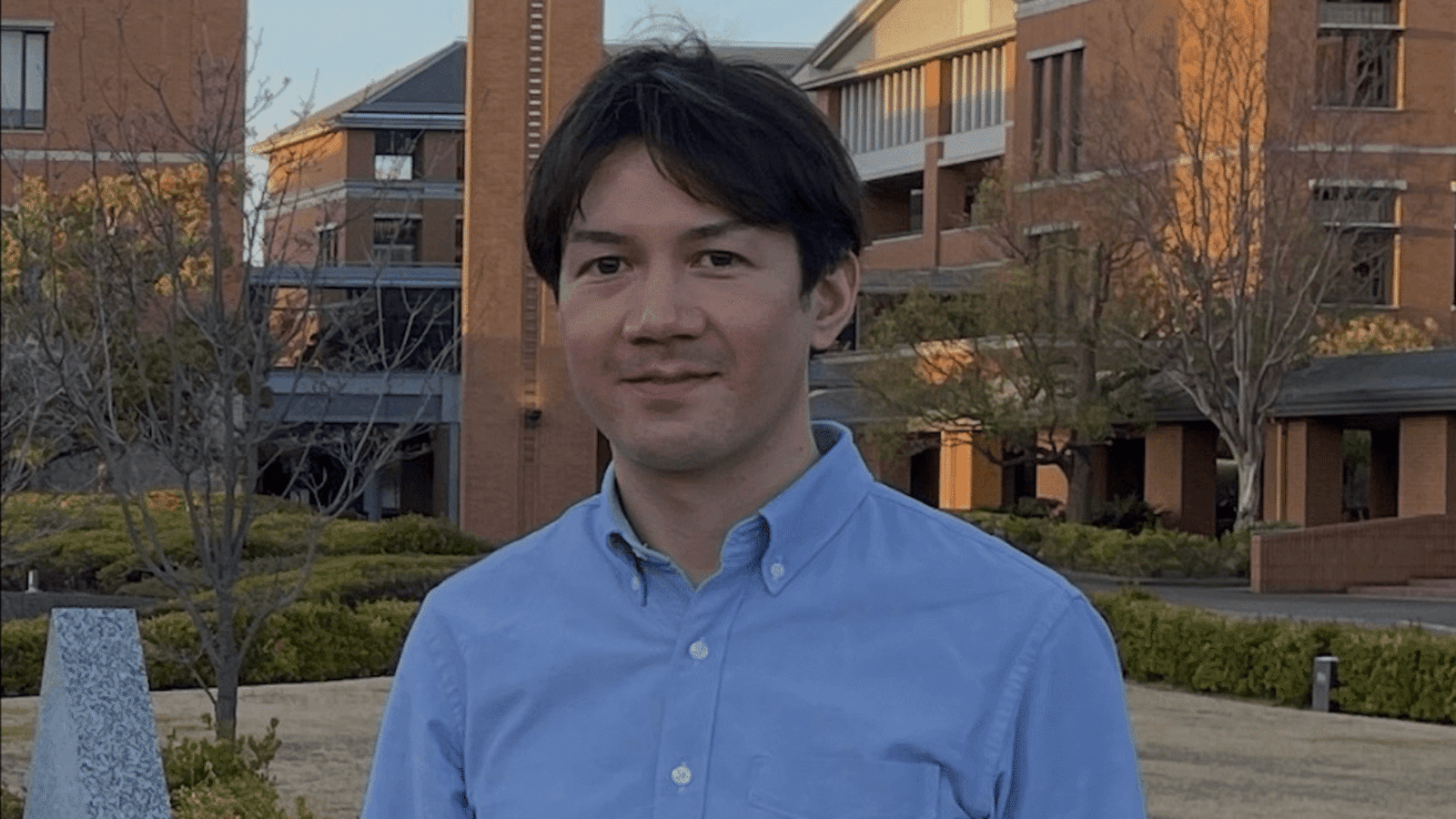

In a wide-ranging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Taro Tsuda—Assistant Professor at the School of Political Science and Economics at Meiji University, Tokyo, and a scholar of Japanese political institutions, party dynamics, and leadership—offers a nuanced interpretation of Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s dramatic rise and governing trajectory. His analysis comes at a pivotal moment: PM Takaichi’s landslide electoral victory delivered a two-thirds supermajority for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its coalition partner, dramatically consolidating executive authority and granting her administration an exceptional legislative cushion. As Japan’s first female prime minister, combining a programmatic conservative agenda with a leadership style widely perceived as both “diligent and tough-speaking,” Takaichi has reshaped the political landscape—strengthening conservative forces while advancing an ambitious policy program that includes fiscal stimulus, proposed consumption-tax cuts, technological and AI-driven industrial strategy, and a more assertive regional security posture. Yet, as Dr. Tsuda emphasizes, these developments should not be misread as evidence of a populist rupture.

Contrary to narratives portraying her ascent as a transformative break, Dr. Tsuda argues that Takaichi’s premiership represents continuity within Japan’s historically institutionalized dominant-party system. “It is definitely the former rather than the latter,” he explains when asked whether the so-called “Takaichi boom” constitutes personalized leadership rather than populism, noting that she emerges from the LDP, “which has been the dominant party in Japan since 1955.”Because populism typically involves an anti-establishment appeal “pitting the population against a harmful elite,” her leadership—rooted firmly within the ruling party’s mainstream—does not fit that model. Indeed, he stresses that her ideas and career path have remained “very much within the mainstream of the LDP,” making it “very hard…to say that her becoming Prime Minister would constitute a populist rupture.” In this reading, even her decisive electoral mandate and willingness to adopt politically risky positions on issues such as Taiwan and China reflect programmatic assertiveness rather than anti-system mobilization.

Dr. Tsuda further contends that Takaichi’s electoral success should be understood as part of the LDP’s adaptive strategy to reabsorb drifting conservative voters and preempt challenger movements. Faced with defections to newer right-leaning parties, the party leadership sought to reconstruct its electoral “big tent,” successfully drawing many of those voters back. This, he argues, forms “a sort of short-term and perhaps longer-term strategy…to prevent that kind of populist challenge to its incumbency.” Her personal popularity proved central to this effort: Takaichi “became the face of the LDP for this election,” attracting independents and younger voters who had previously been skeptical of the party.

By situating Takaichi’s premiership within longer trajectories of LDP dominance, Shinzo Abe’s legacy, and Japan’s evolving security and economic priorities, Dr. Tsuda’s interview highlights how leadership personalization, ideological clarity, and institutional continuity can coexist. The result, he suggests, is not a populist upheaval but a powerful example of how dominant parties renew authority through strategic adaptation—demonstrating that even historic milestones, such as Japan’s first female premiership and a sweeping supermajority victory, may ultimately reinforce rather than disrupt established structures of governance.

Here is the edited version of our interview with Dr. Taro Tsuda, revised slightly to improve clarity and flow.

Rebuilding the LDP’s Big Tent to Preempt Populist Challengers

Dr. Taro Tsuda, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: You characterize the current moment as potentially a “Takaichi boom.” To what extent might this be conceptualized as a form of personalized plebiscitary leadership within a historically institutionalized dominant-party system, rather than a classic populist rupture?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: I would say it is definitely the former rather than the latter. Prime Minister Takaichi is from the LDP, the Liberal Democratic Party, which has been the dominant party in Japan since 1955. There have been several moments when it has lost power, but throughout this whole period—about 70 years—it has remained the dominant or most powerful party. And she comes from that party, so it is difficult , in my definition of populism, that it implies a sort of anti-establishment or anti-elite stance, pitting the population against a harmful elite or establishment, and that is definitely not what Takaichi is doing. So it is very hard for me to say that her becoming Prime Minister would constitute a populist rupture. All her ideas, policy proposals, and her career path have been very much within the mainstream of the LDP, even if one might say they are on the more right-wing or conservative side of the party. So, I would not characterize it as a populist rupture.

In light of your argument that the LDP must reconstruct its “big tent,” can we interpret PM Sanea Takaichi’s strategy as a mode of preventive populism—absorbing and neutralizing anti-system demands before they crystallize into durable challenger movements such as Sanseito?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: I would say, to some extent, that is part of her strategy, or what the LDP’s strategy as a whole was, especially in this past election, the lower house election that took place on February 8. For the past few years, there has been a group of more right-leaning or more conservative voters who have been drifting away from the LDP because of what they perceive as the past few leaders’ more liberal or more centrist approach. Many of them went to new parties like Sanseito. A major goal of the past election was to bring many of those more right-leaning voters back into the LDP, and the results show that, in many ways, they were successful in doing so. Many of the people who were conservative or who had supported Sanseito in previous elections supported the LDP this time.

So I think that this is a sort of short-term and perhaps longer-term strategy of the LDP leadership to prevent that kind of populist challenge to its incumbency.

Downplaying Gender While Subtly Leveraging It

Takaichi’s leadership style appears to combine the novelty of being a prominent female conservative leader with a strong emphasis on themes such as strength, discipline, and national security. Based on your observations, to what extent does she highlight or downplay her gender in shaping her political image and appeal?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: That’s a very interesting and complicated question. From what I’ve seen so far of her leadership since she became LDP party leader and then Prime Minister, it seems that her approach is a delicate balance between downplaying or not explicitly mentioning the gender aspect and, more subtly, sometimes using her gender to gain a favorable impression or to connect with people in Japan. One interesting example is that after becoming Prime Minister, she was asked by an opposition lawmaker to focus on dressing well and wearing Japan’s best materials or textiles, and that as Prime Minister she should not wear rather drab clothes or something like that. In response, she talked about how she is in a difficult position because she has to wear something good so that people take her seriously as a female leader on the international stage, and that she has to think carefully about what she wears.

That was an episode where she usually does not touch upon gender at all, but by talking about things like that—without really focusing on gender itself—she was still using the gender aspect to connect with people. I think that aspect of her leadership is something many of the people who supported her in the recent election appreciate, especially independent or younger voters. They like this personality-based and relatively ordinary style that she often emphasizes, which at times includes a subtle gender aspect. So, I think it is a very subtle approach, not one that explicitly focuses on gender.

Do you think Takaichi’s rise shows that gender matters less in leadership today, or that she succeeds by adopting traditionally masculine leadership traits?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: I would say that it is neither that gender does not matter nor that she is consciously trying to adopt masculine traits. Her example is simply exceptional. On the first point about gender not mattering, I think it still matters a great deal, since Japan, on many measures of gender parity and gender equality, still ranks lower than other advanced industrial countries. There are many barriers for women to achieve leadership positions in Japan, including in politics. She was able to overcome those, and that is part of her appeal to many people.

At the same time, as I mentioned in relation to the previous question, she is not completely denying her gender. She sometimes subtly appeals to people in ways related to it. So I would say it is neither; the fact that she has been able to break some of those barriers is what appeals to many voters in Japan.

Abe’s Legacy as the Informal Architecture of Takaichi’s Rise

Your work on Satō Eisaku highlights the stabilizing function of informal authority and elder statesmanship in moments of systemic uncertainty. To what extent does Abe Shinzo’s enduring legacy function as a form of posthumous informal governance structuring Takaichi’s political maneuverability?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: From your question, I think you’re referring to the extent to which Shinzo Abe’s legacy is significant for Takaichi and her politics. I would say that, in many ways, Abe’s legacy and his career contributed to her rise to the leadership of the LDP and to the Prime Ministership. Because Takaichi is a protégé of Abe, while he was alive he supported her past attempts— the first attempt was while he was still alive, before she was assigned to become leader of the LDP and potentially Prime Minister. She wasn’t successful at that time, but his support helped her get relatively close to reaching that position then. In the most recent leadership contest, when she was able to secure the leadership of the party and then become Prime Minister, the support of Abe’s former faction members was very important. Even though she was not officially a member of his faction, she was his protégé, and many people around him are also supportive of her politically and ideologically, so in that sense it is very important.

Many of her policy ideas are also continuations of Abe’s policy agenda, such as building a more assertive Japan on the international stage and maintaining close relations with the US, including Donald Trump, who had a close relationship with Abe while he was alive. So in many ways, that legacy is very important.

We also have to point out, however, that Abe’s legacy contributed to those factors that have caused recent difficulties for the LDP, such as the political scandals relating to the party’s ties with the Unification Church and the slush fund scandal that focused on the former Abe faction. In those ways, these issues created difficulties for the LDP that Takaichi had to overcome in order to succeed in this past election. So in many different and complex ways, Abe’s legacy continues to be important for Japan’s politics.

Executive Dominance Rising Amid Residual Factional Power

Are we witnessing a transition from factional oligarchy to leader-centered executive dominance, or do factional networks remain the latent institutional infrastructure of LDP governance?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: That’s also quite a complicated question. We can definitely say that the influence of factions is much less in Japanese politics than previously thought. In the sort of golden age of LDP rule during the Cold War, especially during the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, factions were involved in many different aspects of LDP politics and Japanese politics: election strategy, fundraising, and choosing the leader of the LDP, who, because the LDP was the leading party, almost automatically became prime minister. Thus, many aspects of factions were the central units of the LDP’s rule.

But that later diminished because of electoral reform in the 1990s, which, as the election system changed, reduced the factions’ influence in election strategy. Further on, with the scandals I mentioned earlier relating to the Unification Church and ties with the LDP, and especially the slush fund scandal, former Prime Minister Fumiyo Kishida led an effort to dissolve the factions. Almost all of the LDP factions stopped existing, at least on paper, in 2024. One major faction of former Prime Minister Aso Taro still exists, but most of the others have dissolved, which has very much reduced the role of factions.

However, there has been a long history of people in the LDP talking about the need to get rid of factions as a source of corruption and division in the party. There have been earlier efforts to weaken the factions, but what has often happened is that the factions are weakened and then able to come back and become stronger again. So this could happen again in the future, and even if the formal factions are mostly no longer existing, there are still strong informal groupings within the LDP. So, for the moment, factions are much reduced in their influence, but it is still hard to say that they are irrelevant or that they will not become stronger again in the future. At the moment, much less.

Managing Scandal Through Leadership Appeal

Given the LDP’s recent decline due to scandals and erosion of public trust, do you think a strategy of proactively addressing these issues could help restore its credibility, or are patronage-based practices too deeply entrenched for meaningful reform?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: That’s also a very interesting question. A few months ago, I wrote an opinion piece in the Japan Times that addressed this very issue. I wrote it very soon after Takaichi became Prime Minister of Japan, and I argued that this was an opportune moment for her, because she was popular, not only to consolidate support among more conservative voters but also to address the political scandals that had damaged the LDP. I thought her position and her closeness to Abe and Abe’s faction put her in a good position to do this, and that it could also stabilize the LDP’s rule. However, what has happened in the subsequent months is not really what I suggested.

Instead, she has focused more on other policy issues and on her personal appeal with the Japanese public, so the issue of political reform has been put to the side to some extent. She has agreed with the coalition partner—or the coalition partner, the Japan Innovation Party, has emphasized this issue as well—but it is no longer at the forefront. At the moment, it seems she has been successful in turning the page on this issue without directly addressing it.

It remains to be seen whether that can continue. There is always a possibility that a similar scandal could emerge again, although I think the likelihood in the near future may be lower because of the lessons some members learned from these past scandals and because the faction system is now, for the moment, defunct. Still, since she has not addressed it directly, it could return in the future. In the long term, this is something that should be addressed for the country itself and for the stability of the LDP’s rule.

Balancing China Through Alliances and Supply-Chain Resilience

Japan’s security posture is evolving amid intensifying US–China rivalry. Would you characterize Takaichi’s foreign policy orientation as a continuation of post–Cold War embeddedness, or as a move toward strategic autonomy within a multipolar order?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: I think that because of the recent dispute between Japan and China, sparked in part by some of Takaichi’s comments about Japan’s response in a hypothetical contingency relating to Taiwan, many assume that she is departing on a very different path in terms of foreign policy. But as I see it, her policy is, at least at the moment, very much a continuation of the path of some of her predecessors, especially starting with Prime Minister Abe. Abe is known for pioneering the idea of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific, bringing together not only the US and Japan in their alliance but also like-minded countries in the Indo-Pacific to work on a range of economic and security issues, in a form of implicit balancing against China. Some of his successors, such as former Prime Minister Kishida, also committed to boosting defense spending and capabilities in light of the Ukraine war.

I think she is continuing along that path, so I would not say there is a major departure from her predecessors. It is still very much reliant on the US–Japan security alliance, but it also involves reaching out to other countries in the region that share interests and values with Japan, such as India, Australia, and South Korea. She has, perhaps more than her predecessors, forged constructive relations with South Korea, which until recently were quite tense. That is generally the path she is following in terms of foreign policy.

How do you see Japan’s recent focus on economic security and supply-chain resilience — mainly as a response to new global risks, or as part of a broader shift in its economic and industrial strategy?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: In terms of economic security, Japan has always had an interest in it because it is a resource-poor island nation that relies heavily on global trade. Securing vital raw materials and natural resources has therefore always been a major concern and an important factor in its foreign policy.

However, there has been a recent and even greater emphasis on this issue because of developments such as the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and now tensions with China. These events have highlighted Japan’s vulnerability and its reliance on sea lanes and supply chains. There has been an even stronger focus on economic security since the 2020s. The position of Minister of State for Economic Security, now one of the important Cabinet posts, was officially created in recent years; it did not exist before. The creation of this position demonstrates the stronger emphasis on economic security.

Leadership Image as the Engine of Electoral Revival

And finally, Dr. Tsuda, to what degree has Takaichi’s electoral success been mediated through narrative construction—her image as a disciplined, uncompromising, and reformist leader—and how central is this symbolic dimension to sustaining the LDP’s renewed legitimacy in the medium term?

Dr. Taro Tsuda: If you’re referring to the electoral success of this past election in the lower house, that it was very much based on Takaichi herself. Her own brand of leadership and her image were a central part of that election and the success of the LDP. If you compare the support rate of Takaichi with the support rate of the LDP before the election, there was quite a big gap. Even today, there is a gap between the actual support of the LDP and Takaichi’s very high approval rating. So basically, she became the face of the LDP for this election, and many people who liked her and approved of her leadership, but who may have had more skepticism toward the LDP itself, were persuaded to vote for the LDP. This included not only the conservative voters that I talked about earlier, but also many non-party-affiliated voters—people who are not strongly aligned with one party and who can shift their support from election to election—as well as a large number of younger voters, who historically did not support the LDP that strongly. This shows that her image and leadership were very important to the success.

For the medium or longer term, I think that depends on whether she can deliver on some of the things she promised in the election, such as improving the economic situation of the Japanese people and addressing other important issues, including concerns relating to immigration or foreigners in Japan, to mention a few issues that were very prominent in that election. If she can address those issues, I think that will help the LDP in the near future. But if she has trouble addressing them, or if some kind of scandal or other problem emerges, then it may be difficult, even if she herself remains popular, to sustain support for the government as a whole.