In an interview with ECPS, Dr. Samuele Mazzolini argues that Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa has embraced populism not as a vehicle for transformation, but as a strategy to maintain power amid crisis. Recently re-elected after a snap presidency, Noboa has relied on emergency decrees, militarized crackdowns, and anti-crime rhetoric. “Populism has simply served as a means to cling to power and bolster his personal image,” Dr. Mazzolini asserts. Despite branding himself as a technocrat, Noboa “lacks a coherent national project” and governs through “sheer improvisation.” Dr. Mazzolini warns that Ecuador is entering a “permanent state of exception,” with rising authoritarian tendencies and no clear roadmap for reform.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

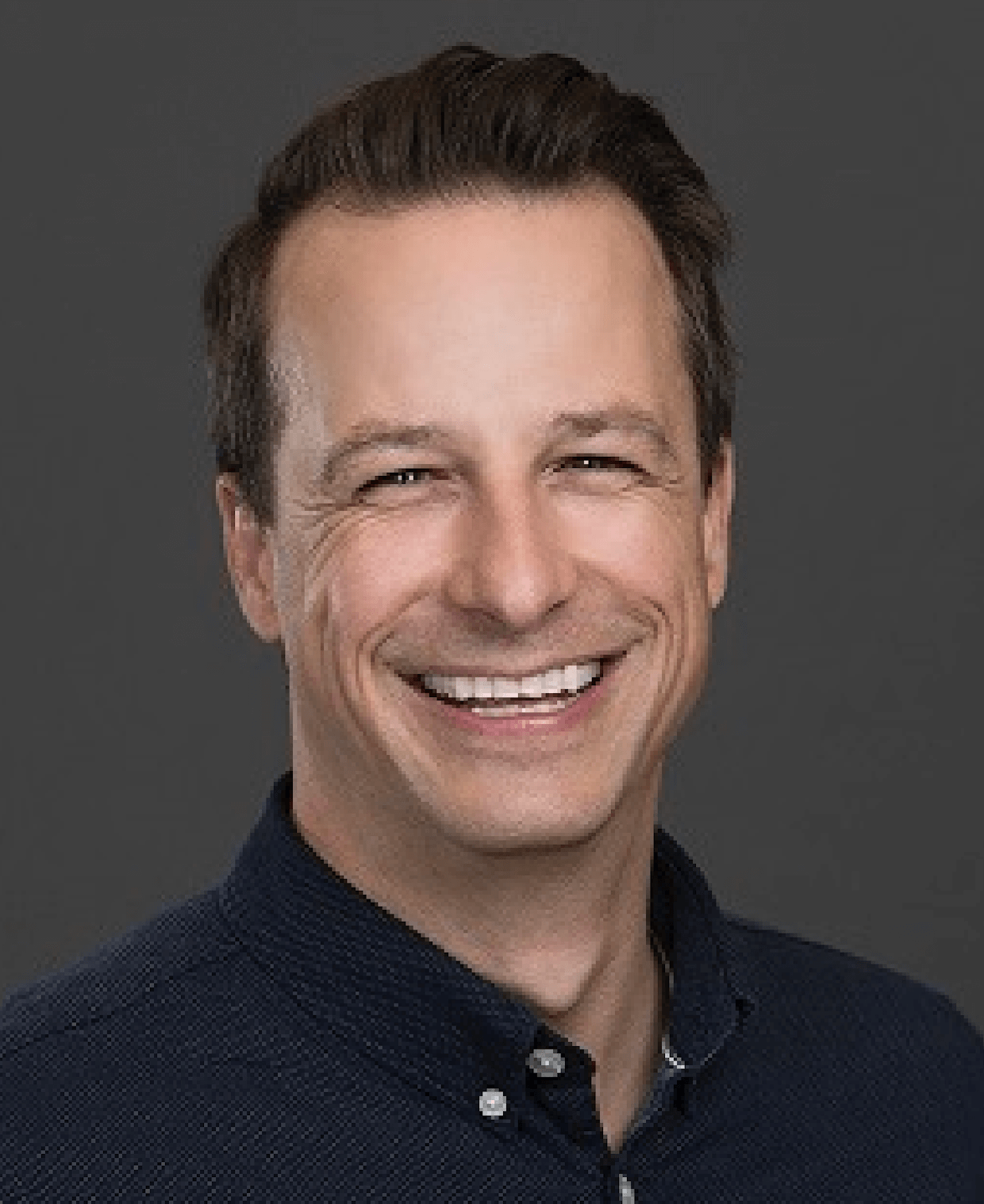

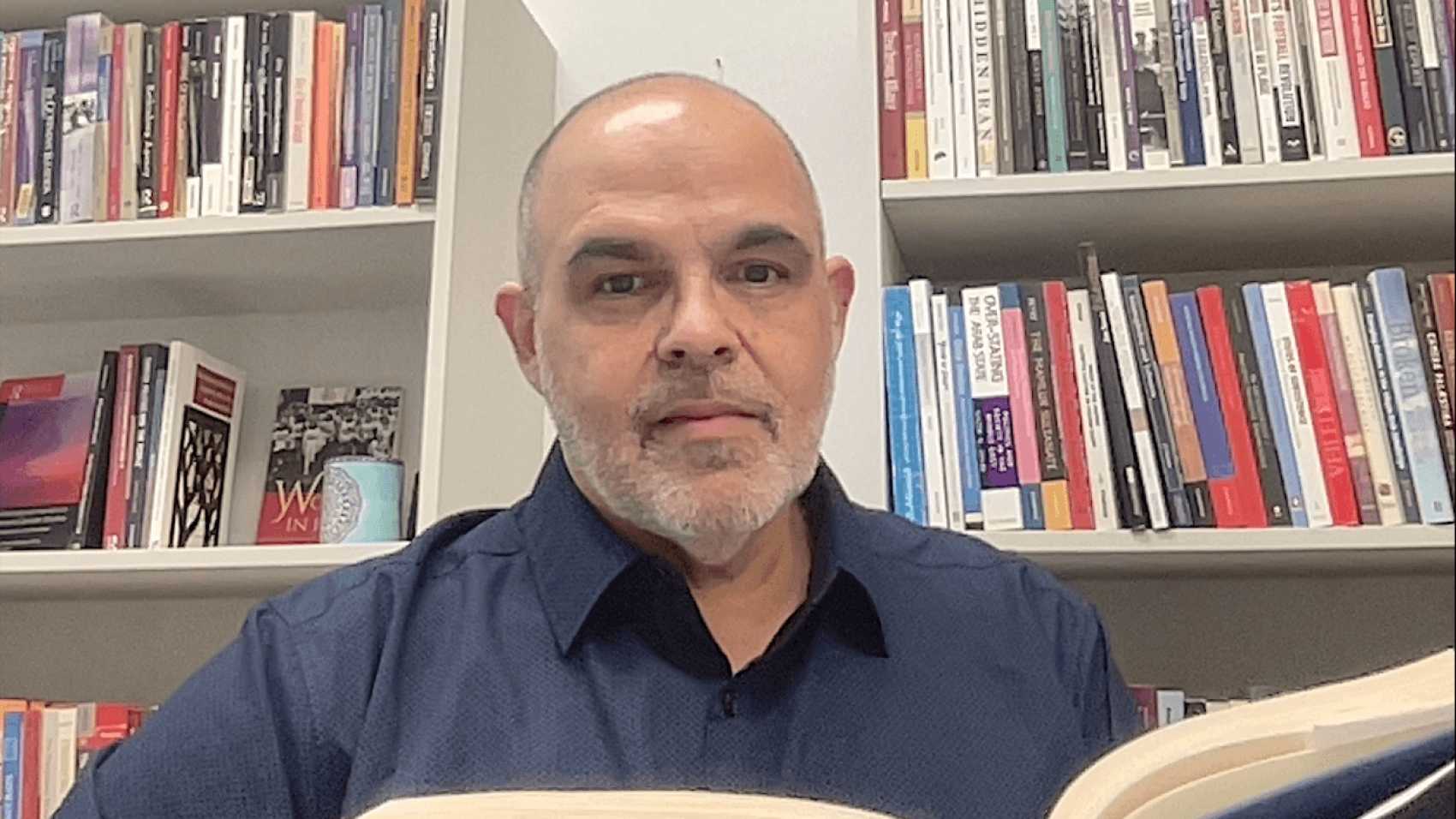

In a sharply observed conversation with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Samuele Mazzolini—Adjunct Professor of Political Science at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice—offers a sobering analysis of Ecuador’s evolving political landscape under President Daniel Noboa. Recently re-elected in the April 2025 run-off, Noboa secured a full four-year term after what he called a “historic” victory. He originally came to power in November 2023 through a snap election and has since defined his presidency by launching a militarized crackdown on Ecuador’s powerful criminal gangs—an approach that has dominated his public image as the country became the most violent in the region.

Despite his win, Noboa’s left-wing challenger, Luisa González, rejected the result, alleging fraud without providing evidence. Against this backdrop of tension and insecurity, Mazzolini argues that Noboa’s political style is not grounded in reform, but in survival. “In Noboa’s case, [populism] has simply served as a means to cling to power and bolster his personal image,” he asserts.

Though Noboa projected a moderate and technocratic profile during his initial campaign, his presidency has taken a decisive right-wing populist turn. “He wasn’t the ‘security candidate.’ That was Jan Topić… But the very moment he took office, he took a different turn,” Dr. Mazzolini notes. Noboa’s embrace of penal populism—relying on military force and emergency powers—has so far failed to reduce violence. “Despite tough talk on crime and gangs, the rates haven’t improved,” Dr. Mazzolini observes.

Crucially, Dr. Mazzolini emphasizes the absence of a coherent political vision. “What are his views on industrial relations? Agricultural policy? Same-sex marriage?” he asks. “There are countless areas where he appears to have no defined position.” Unlike Rafael Correa, whose government—though polarizing—pursued a structured national project, Noboa seems adrift, leaning on improvised alliances and securitarian rhetoric.

As Dr. Mazzolini concludes, Noboa’s presidency appears less like a populist transition toward transformation, and more like the entrenchment of a permanent state of exception: “a deliberate effort to take advantage of the situation… because he saw the opportunity was ripe to consolidate his image.”

Here is the lightly edited transcript of the interview with Dr. Samuele Mazzolini.

Securitarian Populism, Not Technocratic Reform

Professor Mazzolini, thank you so very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: How should Daniel Noboa’s recent electoral victory be interpreted within the broader trajectory of populism in Ecuador? Does it signify a new phase in the evolution of populist politics in the country, or a rearticulation of existing populist paradigms under a technocratic-securitarian guise?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: There has certainly been a shift toward a kind of penal populism—one that places heavy emphasis on delivering security, increasing national safety, and attempting to curb the unchecked expansion of criminal gangs in Ecuador. So yes, it is clearly a rearticulation of populism under a securitarian guise.

However, I wouldn’t say there’s much technocracy at play. If you look at Noboa’s first year and a half in office, it’s been marked by sheer incompetence, indolence, and a general lack of professionalism. There hasn’t been much evidence of technocratic governance—despite the polished image he projects.

Daniel Noboa is a young figure, fluent in English, US-educated, and he carries himself well. But if you examine his actual decisions and decrees over the past 18 months, they leave a lot to be desired. So, again, I don’t see technocracy; I see a strong security discourse that, in practice, hasn’t delivered. If you look at the numbers, despite tough talk on crime and gangs, the rates haven’t improved. Ecuador remains a very unsafe place, and the population continues to live under the grip of organized crime.

Do you see Noboa’s re-election and hardline tactics as signaling a right-wing variant of the populist-institutional tensions you identified in Rafael Correa’s government?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: Certainly. When populist politics is prolonged, it becomes increasingly difficult to construct a stable institutional framework. To put it plainly: unless you succeed in redefining the identity of your adversaries, establishing durable institutions becomes a serious challenge. This requires a transition from a polarizing strategy to one that reintegrates opponents into the emerging order. It’s essential to ensure that the system you build does not unravel or get overturned the moment you leave power.

In that sense, yes, a parallel with Correa can be drawn. Under Correa, there were clear tensions between populist rhetoric and the broader project of institution-building. However, I see two key differences. First, Noboa has been in power for a very short time—just about a year and a half—which is hardly sufficient, even for a populist, to fully articulate a political vision or begin the process of reintegrating adversaries.

Second, and more importantly, Noboa doesn’t appear to have a project for the country. His governance so far seems driven by sheer improvisation. When he was first elected in 2023, I don’t think he expected to win. My impression is that he aimed to perform well to position himself for future elections, but unexpectedly found himself president.

Historically, the Ecuadorian right has lacked a solid, coherent project for the country—aside from capturing the state and bending it to create a more favorable environment for business. In that sense, I doubt he has any clear long-term vision. Let’s see how his plan for a Constituent Assembly develops. He apparently wants to change the current constitutional framework—reversing the progressive constitution drafted under Correa in the early 2000s, which emphasized rights, state planning, and redistribution.

Many fear that his goal is to do away with these provisions and instead draft a new constitution that minimizes rights and reduces the state’s role in planning and redistribution. The intention seems to be to create a more business-friendly climate for both foreign and domestic investors. In short, it looks like a push to take the country back to the neoliberal era.

Noboa’s Populist Signature: Militarization Without Accountability

How does President Noboa’s militarized crackdown on crime reflect elements of penal populism, and in what ways does it diverge from traditional Latin American law-and-order populism?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: A major difference lies in the involvement of the armed forces. If you recall, from the very beginning of his mandate, he declared a state of conflict—he said there was a war going on with criminal gangs—and brought in the armed forces to collaborate with the police in the fight against organized crime. That’s something new. However, it should be noted that the armed forces are not properly trained for patrolling the streets; their training is very different. So I’m not sure how effective they are in that context, and so far, the statistics do not seem to suggest they’ve been particularly useful.

Another major concern is the blatant disregard for human rights and international law. Take, for instance, the case of the four boys from Las Malvinas, a neighborhood in Guayaquil, who were kidnapped, tortured, and brutally killed by the armed forces. And that is just one example—it reflects a broader climate of impunity for the military and police acting under presidential orders. There have been numerous other reports of abuse and extrajudicial disappearances—people who simply vanish—many of whom have no ties to organized crime. A significant number of these victims are Afro-Ecuadorian or individuals with darker skin tones, introducing a deeply troubling racialized dimension to the violence.

What’s even more alarming and horrifying is the way Noboa’s government has shielded the armed forces and police when such cases have come to light. His handling of the case of the four boys from Las Malvinas reveals a complete disregard for human rights. Now that he has won the election, I believe he will feel even more empowered to continue these measures, while the armed forces are likely to feel increasingly emboldened and protected in carrying out further abuses.

Another example I want to highlight—one that also illustrates how Noboa interprets populism—concerns a serious violation of international law. Take the case of former Vice President Jorge Glas, who had been subjected to lawfare under previous administrations, including the current one. At one point, he was free and sought refuge in the Mexican Embassy in December of last year, after it appeared that Mexican authorities were prepared to grant him asylum. What followed was extraordinary: Ecuadorian police forces stormed the embassy, forcibly removed Glas, and reportedly mistreated embassy personnel. This was a clear and blatant violation of international law. Noboa clearly showed no concern. You might not agree with how the Mexican authorities handled the situation, but there are certain lines that simply should not be crossed. Noboa clearly doesn’t care. By violating international law so blatantly, he presented himself to the public as a leader who doesn’t hesitate to take bold, forceful action. In doing so, he bolstered his image—but in my view, it was a reckless and dangerous step.

Authoritarian Populism Disguised as Emergency Governance

Can Noboa’s extensive use of emergency decrees and military deployments—especially during the election—be seen as a textbook case of authoritarian populism? What democratic vulnerabilities does this strategy expose?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: Yes, definitely. We’re witnessing a clear erosion of democratic standards with the emergence of deeply concerning authoritarian tendencies. The continuous state of emergency, the repeated trampling on the rule of law—these are patterns that go beyond Ecuador and are part of a broader trend in Latin American politics. There has always been a tense relationship between populism and the rule of law, that’s for sure. But I think Noboa is taking it a step further.

We’ve seen extensive use of judicial and electoral institutions for his own political ends. As I mentioned earlier, he has guaranteed impunity for the actions of the armed forces and the police. We also saw the strategic use of state-issued vouchers right before the election to secure electoral support—classic clientelist, patronage politics. All of these elements point to a serious erosion of democracy in Ecuador, and it’s something that must be watched very closely.

The only remaining institutional check on Noboa at this point is the National Assembly. He does not have an overwhelming majority there, so he will face resistance in pushing his agenda through formal channels. Still, as we’ve seen many times, there are ways around the Assembly—whether through buying off deputies, forming opportunistic coalitions with new parties, or simply pushing forward presidential decrees.

In short, yes—this is very much a textbook case of authoritarian populism, carried out under the pretext of combating criminal gangs.

Securitizing Crisis to Consolidate Power

Do you interpret Noboa’s invocation of an “internal armed conflict” and the framing of criminal gangs as terrorist threats as part of a broader global trend of securitizing social crises through populist narratives?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: Right-wing populism has long prioritized the promise of law and order, placing strong emphasis on crime—whether real or perceived. Often, it is not actual crime statistics but the perception of insecurity, amplified by media narratives, that shapes political responses. In Ecuador’s case, however, the threat is tangible. Crime is a major issue, and the situation has spiraled out of control. The country currently has the highest homicide rate in the region and one of the highest globally. Noboa has taken advantage of this by going a step further—invoking the notion of an “internal armed conflict” and framing criminal gangs as terrorist threats. These groups are indeed violent and organized, but his approach reflects how power is being exercised.

From an analytical standpoint, social crises and security crises are not synonymous, though they often intersect. One may contribute to the other, but the relationship is not automatic. Ecuador has long suffered from poverty and poor economic indicators; these challenges predate the current security crisis. What we are witnessing now is a specific interpretation of how to address security threats—one that cannot be fully explained by social conditions alone. In Ecuador’s case, several additional factors are at play: the partial end of Colombia’s armed conflict, the decision by Mexican cartels to use Ecuadorian gangs as local proxies, and the retrenchment of the state since the Correa era. Following Correa’s departure, state institutions have become less present and less embedded in local territories, creating space for international criminal organizations to establish and consolidate power.

So, as you can see, this is a multifaceted problem that security experts are actively analyzing. Noboa’s brand of right-wing populism has seized upon it to construct a tough-on-crime persona. But, as I’ve already mentioned, the methods he’s employed—particularly the carte blanche given to armed forces and police—don’t appear to have delivered effective results. To address a security crisis meaningfully, you also need to resolve underlying social issues. What’s needed is a far more integrated, comprehensive approach.

Is Noboa’s security offensive more a case of populist responsiveness to widespread public fear, or is it better seen as a calculated strategy for consolidating executive power under the guise of emergency?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: It can be seen both ways. One doesn’t exclude the other. What is striking here is that there seems to be a deliberate effort to take advantage of the situation—a sort of “going populist” because he saw the opportunity was ripe to consolidate his image. When he was a candidate in the previous elections, he came across as a moderate—someone who aimed to rise above the cleavage between Correísmo and anti-Correísmo. He presented himself as a centrist, with even some left-leaning ideas, showing particular concern for the poor.

He wasn’t the “security candidate.” That was Jan Topic—a different figure entirely, who boasted about having worked as a mercenary in various war zones. Of course, everyone talked about crime—it’s been a recurring theme in Ecuadorian electoral campaigns over the last five years—but security didn’t appear to be Noboa’s strongest point, nor the reason people chose him over others.

However, the very moment he took office—and after a fleeting parliamentary collaboration with Correísmo—he took a different turn. He adopted a right-wing populist stance, emphasizing a tough-on-crime approach through extensive deployment of the armed forces, the use of emergency decrees, curfews, and similar measures.

Populism Without a Project Becomes a Tool for Survival

You’ve characterized populism as a “transitional device.” In Noboa’s case, is this transition leading toward a reconfigured institutional logic—or is it entrenching a permanent state of exception?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: Yes, I have characterized populism as a “transitional device”—but that’s, of course, when you conceive of populism as a strategy tied to a broader project, a vision for steering society in a particular direction. In that sense, populism serves as a transitional mechanism toward a defined societal transformation. However, not all populists understand or employ populism in that way.

In Noboa’s case, it has simply served as a means to cling to power and bolster his personal image. So yes, I do think he is entrenching a permanent state of exception. We’ll see what happens next—I’m particularly curious whether he’ll try to normalize his authority through the Constituent Assembly. But as I mentioned earlier, I don’t see him as someone with a coherent vision for the country. What are his views on industrial relations? Agricultural policy? Same-sex marriage? There are countless areas where he appears to have no defined position.

This stands in stark contrast to Correa’s project. Whatever one may think of it, that administration had a plan. Its implementation had flaws, certainly, but at least it pursued a clear direction. Noboa, by contrast, seems adrift—focused only on defending his own wealth and that of his class.

In your work on Podemos and M5S, you stress how populism’s success depends on context. Does Noboa’s popularity, despite rising violence and economic decline, suggest that right-wing populism thrives better under structural crisis than left variants like Correísmo?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: It must be noted that right-wing populism benefits from significantly more favorable media coverage. In most cases, powerful interests tend to be far more lenient—and even benevolent—toward right-wing populist actors. The kind of pressure they exert is markedly different from what left-wing variants face. In this sense, right-wing populism is often better equipped to withstand structural crises, constraints, and even blatant shortcomings than its left-wing counterparts.

Additionally, it’s important to consider that Noboa has only been in power for a relatively short time. Many people might think, “He’s only been in office for a year and a half—let’s give him some credit and see how he performs over the next few years.”

Another important point is that, despite Noboa’s poor performance during this period, anti-Correísmo remains a powerful political sentiment. Similar dynamics can be observed in other countries—for instance, strong anti-PT sentiment in Brazil or anti-Kirchnerismo in Argentina. These are not coherent political forces—they’re heterogeneous—but they are united in their strong opposition to former left-wing leaders, for a variety of reasons I won’t delve into here. However, once this broad demographic finds a figure who gains some popularity, they’re often willing to extend that figure a political blank check.

Until Noboa, the right wing in Ecuador was highly fragmented. First, there was Guillermo Lasso, who quickly squandered his initial popularity. In the previous election, multiple right-wing candidates competed for prominence. Now, a single figure has emerged. Interestingly, Noboa has undergone a shift. While he was always opposed to Correísmo, he wasn’t initially a staunch anti-Correísta and didn’t emphasize that stance heavily. Now, however, it has become a central theme of his rhetoric. He polarizes the country by framing the political landscape as a battle between good and evil. As he put it the day after the elections: on one side, the good forces; on the other, the evil ones—into which he groups criminal gangs, Correa, his allies, and his candidate, Luisa González. He draws a clear equivalence between them.

That rhetoric has been strongly supported by the media, which has—without any evidence—suggested that Correísmo is tied to drug trafficking and criminal networks. That’s classic populist rhetoric, and it’s paying off. So yes, I do think that, for the time being, even in the face of structural crises, Noboa can maintain high popularity. But let’s see what happens next.

Populists Govern Through Deals, Not Durable Coalitions

Do Noboa’s coalition maneuvers—including fleeting alliances with Correístas—represent pragmatic populist adaptation, or are they symptomatic of Ecuador’s deep political fragmentation?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: Populists need to ensure they can actually govern. Remember the example of Alexis Tsipras in Greece back in 2014. The circumstances forced him to form a parliamentary alliance with a right-wing party. Also, as I mentioned before, the initial period of Noboa’s time in power can’t really be considered fully populist. So I think it’s quite typical for populists—especially those without solid backing in parliament—to seek temporary alliances as a way to navigate governance.

Another, much riskier route is what Correa did back in 2007. He didn’t have a majority in parliament—actually, he had no presence at all, since he didn’t run any parliamentary candidates—yet he won the presidency. What he did was call for the election of a Constituent Assembly, which then overrode the National Assembly. In that way, the National Assembly was bypassed. It was a very risky gamble that could have backfired, but in the end, it worked and paved the way for his political rise. However, that’s not something all populist leaders can easily replicate—especially because organizing elections for a Constituent Assembly means you need to win an overwhelming majority.

Let’s see now what happens in parliament and whether Noboa will consider something similar. If he faces significant problems in the National Assembly, he might want to pursue a strategy like Correa’s. I’m just speculating here—there are no current rumors of that sort—but under Correa, the Constituent Assembly took over standard legislative tasks during its term, so that could well be an option.

And lastly, Professor Mazzolini, corruption scandals like Metástasis and Purga have revealed links between state actors and organized crime. How should we understand this intertwinement through the lens of populist governance and criminal co-governance?

Dr. Samuele Mazzolini: To be fair, I’m not so sure populism has much to do with this. If you look at the two scandals, the individuals involved included some politicians, but were mostly state officials—particularly within the judiciary and police—who colluded with organized crime. So I’m not convinced populism is central to this dynamic. It seems more closely tied to weak state institutions, which have historically been fragile and vulnerable to collusion with criminal groups.

Now, the situation is even more dire, as these criminal organizations have become significantly more threatening. Imagine a peripheral judge who is being bribed and simultaneously threatened with violence against himself and his family. If the state lacks the strength to provide protection, if it doesn’t offer stable career paths or a strong institutional culture for its officials, it becomes far more susceptible to this kind of corruption and infiltration.

So again, I wouldn’t necessarily bring populism into the picture here. Honestly, I don’t think it plays a significant role.