In an interview with ECPS, Dr. Mom Bishwakarma reflects on Nepal’s September 2025 uprising, widely described as a Gen Z revolution. While youth mobilization toppled a government and ignited debates on corruption and “Nepo baby” privilege, Dr. Bishwakarma warns that deeper inequalities remain untouched. “Basically, we can say this has brought some destruction to political institutions, but not real change,” he stresses. Despite promises of inclusion in the 2015 constitution, caste discrimination and elite dominance persist, leaving Dalits marginalized. Drawing parallels with Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, he cautions that without dismantling entrenched structures, Nepal risks repeating cycles of revolt and disappointment rather than achieving a genuine democratic transformation.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

The September 2025 youth-led uprising in Nepal, widely framed as a Gen Z revolution, has generated global debate about the prospects for democratic renewal in post-conflict societies marked by entrenched inequality and elite capture. To probe the deeper social and political implications of this moment, the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS) spoke with Dr. Mom Bishwakarma, researcher in the Department of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Sydney and sessional academic at the University of Tasmania, Australia. A specialist on caste politics and Dalit struggles for justice, Dr. Bishwakarma situates the uprising within Nepal’s broader trajectory of populist-authoritarian bargains and incomplete democratic transformation.

At the heart of the movement, he explains, was not caste or identity politics but a narrowly defined resistance against corruption and “Nepo baby” privilege. As he notes, “To be honest, it has not really addressed the issue of caste inequalities… Instead, they were primarily resisting forms of ‘Nepo baby’ privilege and the elitism of the ruling class.”This narrow focus, centered especially on the government’s attempt to ban social media, created mobilization energy but left deeper structures of inequality intact.

Digital platforms played a pivotal role, enabling new forms of youth subjectivity while simultaneously constraining the scope of protest. “Youth use social media as a means of organization and as a medium to express discontent against various problems,” Dr. Bishwakarma observes, yet he underscores the limits of such digitally mediated politics in a semi-feudal society where caste discrimination remains pervasive. For Dalit youth in particular, visibility remained minimal: “We can’t see even a single person leading the Gen Z movement… This means that the protest was not specifically raising the issue of caste inequalities or other forms of discrimination in Nepal.”

The uprising also revealed the fragility of Nepal’s federal constitutional order. Despite provisions for inclusion, everyday discrimination remains widespread, with law enforcement institutions often biased and ineffective. For Dr. Bishwakarma, this gap underscores a sobering conclusion: “One legal provision alone does not guarantee rights, nor does it prevent the persistence of discrimination nationwide.”

Above all, he stresses that the uprising has not yielded the systemic change many anticipated. “Basically, we can say this has brought some destruction to political institutions, but not real change. People were expecting deeper reform, but this political outcome has not been delivered. I am not very hopeful that it will bring the transformation the country needs.”

Drawing parallels with Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya and Bangladesh’s 2024 uprising, Dr. Bishwakarma warns that Nepal too risks sliding into cycles of disappointment unless its youth movements move beyond symbolic anti-elite populism toward a deeper confrontation with caste, inequality, and authoritarian legacies.

Here is the transcript of our interview with Dr. Mom Bishwakarma, lightly edited for clarity and readability.

The Uprising Changed the Government, But Not the System

Dr. Bishwakarma, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: Analysts frame the September 2025 uprising as a Gen Z revolution. From your perspective, how did entrenched caste-based inequalities and elite hegemony intersect with rising youth discontent to generate this rupture? And to what extent should we interpret this upheaval as a repudiation of Nepal’s long-standing populist-authoritarian bargains between ruling elites and marginalized publics?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: Thank you so much for this opportunity. Of course, we have to look at the recent political uprising in Nepal from different perspectives. From the point of view of caste inequality, this movement could certainly have done much more. To be honest, it has not really addressed the issue of caste inequalities. Basically, Gen Z started this movement against corruption and against any form of elite hegemony in Nepal’s ruling system. In that sense, it was broadly against discrimination, but more specifically it focused on corruption and on the government’s attempt to ban social media.

In this regard, I should say that caste issues have not been central to the Gen Z movement, and they have not been explicitly addressed. I know this is a very difficult and important issue in Nepal, but at this stage Gen Z could not directly confront caste inequalities. Instead, they were primarily resisting forms of “Nepo baby” privilege and the elitism of the ruling class. As a result, the movement did not specifically take up the concerns of marginalized communities. So, I would conclude that the uprising was not directed against caste discrimination or other forms of discrimination per se. It was mainly targeting corruption in Nepal.

Much of the mobilization was digital and youth-led. How do you interpret the relationship between Nepal’s semi-feudal social order and the emergence of digitally mediated political subjectivities among Gen Z, particularly in light of global debates on how new media both enables and disciplines democratic dissent?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: Looking at Nepal’s recent development process, social media has been one of the areas where there has been massive change — a significant digital transformation, we might say. Basically, access to phones and social media has been a really important shift. That is the main reason why Gen Z became affiliated with each other in different groups, formed associations, and started creating resistance against corruption and other issues.

But looking at society itself, Nepal is still semi-feudal, with persistent discrimination and many challenges yet to be addressed. Digitalization, moreover, has not penetrated rural areas or many other parts of society. So yes, young people are very comfortable with social media, and they are using this tool to raise issues and push for change. Essentially, youth use social media as a means of organization and as a medium to express discontent against various problems. However, they have not fully engaged with the deeper social issues or the root causes behind them. They could have raised concerns about caste inequalities, other forms of inequality, poverty, underdevelopment, or unemployment — all of which would have been valuable. Instead, they focused mainly on two issues: corruption and the government’s attempt to ban social media.

This narrow focus has not created a real chance for broader change in Nepal, nor has it produced significant transformation in other areas. Yes, of course, the uprising changed the government, but at the end of the day, we are not seeing the outcomes that many people in Nepal were hoping for or expecting.

Nepo Babies Have Been Resisted, But Caste Discrimination Has Been Left Untouched

The discourse against “nepo kids” suggests a moral economy of resentment. Do you see this as a continuation of older struggles against caste privilege and elite reproduction, or as a qualitatively new form of digitally amplified populist class politics rooted in spectacle and affect?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: This Nepo babies movement is essentially rooted in social media. Of course, it stands against any form of elite hegemony in the country, but it is not directly addressing the issue of caste discrimination. We can see that in the leadership of the Gen Z movement, not many youths from so-called marginalized or lower-caste groups are represented. They are not in leadership positions, nor are they given that opportunity.

Many young people from different classes and communities may have joined the resistance, but they remain outside leadership roles. So, in essence, this is more of a symbolic resistance against elite hegemony or authoritarian governance, rather than a movement that specifically addresses caste or other marginalized groups. It is, in effect, resistance against political leaders, Nepo babies, and elite authoritarianism in Nepal.

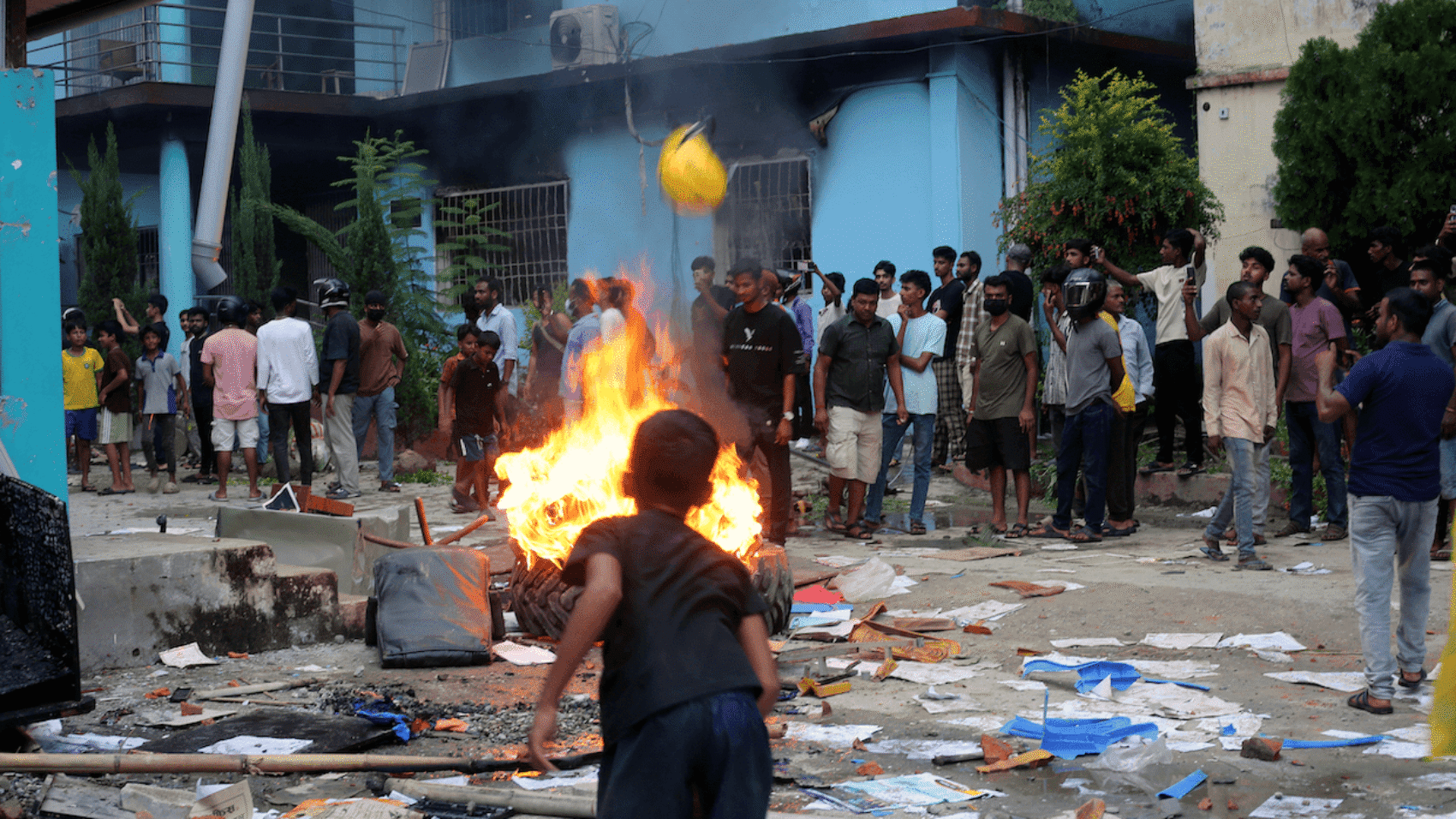

With symbols of state power set ablaze, some argue the uprising reflected anarchic nihilism, while others see a democratic re-founding. Do you interpret this as a destructive rejection of institutions, or as the embryonic formation of what might be called a post-elitist and post-authoritarian democratic imagination?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: We have to look at this from two perspectives. Yes, of course, we can see it as post-elitist, or an anti-elitist movement, and there is a reimagining of a new democratic process in Nepal. But the way it has unfolded in the political system, particularly after the uprising and the formation of the interim government, shows that they are still working within the current constitution, and there has not been much change in the governance system.

Gen Z demanded a directly elected prime minister or a directly elected president, reforms in the electoral system, and strict action against corrupt political parties, but not much of this is happening. After the uprising, an interim government was formed, led by the former Chief Justice and other independent leaders who are very well known in the country, but they are still operating under the articles of the existing Constitution. This means there has been no suspension of the Constitution.

There is no guarantee of a directly elected prime minister or president. There is no guarantee of a new electoral process that would ensure representation of all communities, including marginalized groups. In other words, there has not been a real outcome from this process. So, basically, we can say this has brought some destruction to political institutions, but not real change. People were expecting deeper reform, but this political outcome has not been delivered. I am not very hopeful that it will bring the transformation the country needs.

What Nepal Needs Is Total Reformation, Not Symbolic Change

Your book stresses the twin imperatives of redistribution and recognition in the struggle for Dalit justice. Do you see Nepal’s Gen Z revolution as embodying these imperatives—or does its populist anger risk collapsing recognition into resentment and redistribution into vague anti-elitist rhetoric?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: Thank you for this question as well. I would again like to emphasize that, yes, we are expecting much more change, deeper change, or reformation. As I stated in my book, to address the issues of Dalit and other marginalized groups in Nepal, there must be total reformation — both redistribution of state resources and recognition of communities like the Dalits in Nepal. But after this youth-led or Generation Z-led uprising, we are still not seeing much redistribution, nor is total reformation likely to happen in the country.

This means there is still a great deal to be done, even though the Constitution of Nepal in 2015 addressed a wide range of issues — for example, social inclusion, the republican system, and different forms of governance, such as local, federal, and state government. Many things were introduced with that new constitution, but there has not been real change regarding caste discrimination and other forms of exclusion.

Young people, in particular, are looking for rapid change and fast development in Nepal, which has not materialized, either after 2015 or, if we look back further, after 2006, when the republican system was introduced in 2008. People expected much more meaningful change so that there would be development, opportunities, and inclusion. Yes, there was some symbolic inclusion in Parliament and in other mechanisms — Dalits and other marginalized groups were included, as were women and other communities — but in rural areas, ordinary people did not feel the impact.

There has continued to be high unemployment and high corruption. So, from that perspective, yes, there is still much to be done in Nepal, and what is needed is total reformation rather than symbolic change. This particular uprising is indeed a revolt or resistance against elite authoritarianism, but it is not producing meaningful change, nor is it bringing about the kind of total reformation Nepal needs.

Despite legal prohibitions, everyday caste discrimination persists. To what degree do Gen Z protests transcend entrenched caste boundaries, and how do you assess whether Dalit youth achieved disproportionate visibility—or conversely remained marginal—in this anti-authoritarian mobilization?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: Thank you so much for this very good question. As I stated before, Dalits once again seemed to be marginalized in this process, because we can’t see even a single person leading the Gen Z movement. If you look at the composition of Gen Z leaders, I don’t see any Dalit in that position. Of course, there were a couple of people killed during the protest, and there are other incidents as well, but in terms of leadership, I can’t see any Dalit member included in that process. This means that the protest was not specifically raising the issue of caste inequalities or other forms of discrimination in Nepal. It was more focused on anti-corruption and the ban on social media. Yes, of course, that is really important for the development of the nation, but when it comes to issues like caste inequalities, other forms of discrimination, and many broader social concerns, they have not really been addressed at this stage. That’s why I am again saying that, in the case of caste and other forms of discrimination, we need another form of revolt or resistance that truly addresses the issue of caste, so that there will be no discrimination, and marginalized communities will have more opportunities and be able to develop in Nepal.

Without Effective Mechanisms, Discrimination Persists Nationwide

Federal restructuring and the 2015 constitution promised inclusive representation, yet inequalities remain deeply institutionalized. Did the 2025 uprising expose the limitations of Nepal’s federalism as a tool for substantive equality, or was it more a populist indictment of the state’s moral legitimacy?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: I’ve already mentioned this issue before, but I would like to emphasize again that, yes, the 2015 Constitution specifically addressed social inclusion. Because of that constitution, there is representation of marginalized groups, including Dalits, women, and other ethnic communities, in Parliament as well as in local and state government. But it has not directly addressed caste inequalities or everyday discrimination.

Discrimination remains widespread across the country. The government’s law enforcement mechanisms are either ineffective or deeply biased, which is why existing laws are not being properly implemented. Yes, there is legislation against caste-based discrimination — an act from 2000 that was enforced after 2011 — and the 2015 Constitution also clearly states that caste discrimination is illegal.

There are rights on paper for Dalits and other marginalized communities, but one legal provision alone does not guarantee those rights, nor does it prevent the persistence of discrimination nationwide. What is needed is an effective implementation mechanism, such as police and administrative institutions, that take the issue of discrimination seriously. At the moment, such mechanisms are absent, and there is also a lack of Dalit representation within law enforcement itself. This creates a vacuum and leaves little hope for people, especially those from lower-caste and Dalit communities in Nepal.

Critics warn that anti-corruption and anti-nepotism discourses can be easily co-opted by authoritarian populists who claim to “purify” politics while entrenching new hierarchies. Do you see parallels between the risks inherent in caste-based identity mobilization and the dangers of these new anti-elite narratives?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: Of course, I agree with that point, because this present youth uprising, or Gen Z movement, is against elite authoritarian government systems and the leaders who were running the government in Nepal. But there is always the issue of caste identity and representation. Most of the leaders of the Gen Z movement are again from higher castes, and there are not many Dalits or other marginalized groups included in leading positions or processes. This clearly shows that caste inequality and caste identity have not been specifically addressed through this uprising, even though they could have been. The core issues of the movement were essentially anti-corruption and opposition to the social media ban. This means they did not give much attention to other social problems, such as caste discrimination, unemployment, and broader structural inequalities. That is why there is always a risk: if the youth and others involved in such movements do not fully understand Nepal’s social fabric, history, and the deeper changes needed, their mobilization risks remaining superficial.

Another point I want to emphasize is that, even though these young people are driven by social media and digital transformation, their mindset is still shaped by their families, parents, and society. Many come from elite backgrounds and continue to enjoy caste privilege. That is the real risk and danger. It means that, in the future, even if they come to power — whether as ministers or prime ministers — they are unlikely to directly address caste discrimination or other forms of marginalization. That remains a serious danger in Nepal’s current context.

People Expected Faster Progress on Corruption and Development

Nepal’s Maoist insurgency once mobilized Dalits and marginalized groups in large numbers, but its legacy was one of institutional capture and elite circulation. How do today’s youth movements relate to—or explicitly repudiate—this Maoist populist-authoritarian inheritance?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: Many people now view the Maoist revolt as another form of elite authoritarian process, and in that sense, it did not fulfill expectations. But we also need to look at it from a historical perspective. Nepal was then ruled by a king, opportunities were very limited, and although there was democracy, there was little real progress and no meaningful inclusion. After the Maoist movement, however, many things did change.

For example, the issue of inclusion was strongly raised, and afterward a new constitution was promulgated. That constitution guaranteed social inclusion, secularism, and a republican federal system in the country. Still, these gains did not translate into substantial improvements on the ground. Change was happening, but people were expecting much faster progress in addressing corruption, unemployment, and development. Corruption, in particular, was a major issue, and while the Maoists attempted to address it when they came to power, they ultimately fell short.

This led to political shifts. The main parties, like the Nepali Congress and CPN-UML, came together, formed a coalition, and removed the Maoists from power. So elite resistance was strong. At the same time, many argued that the Maoists themselves had become elitist, were involved in corruption, and failed to deliver real change. That became a major criticism of the Maoist Party.

Another structural issue was the electoral system. The Maoists favored a full proportional system, but the 2015 political settlement established a first-past-the-post system. This system made it almost impossible for any single party to win a full majority, leading to frequent coalition governments and instability. That is also why the recent youth uprising demanded reforms: a directly elected prime minister or president, a different electoral system, and a state-funded electoral process.

But even after this uprising, none of these demands have materialized. With Parliament dissolved, constitutional amendments cannot move forward. We now have to wait and see what the interim government does. One of its mandates is simply to hold another election. After that, we will see whether a single party can secure a majority, or whether a youth-led party will emerge and participate in the elections. These are the developments we will need to watch in the future.

Dalit Politics Requires Both Recognition and Redistribution

Your scholarship emphasizes Dalit demands for recognition alongside material redistribution. Do you think the revolutionary anger of Gen Z risks dissolving such group-specific claims into a homogenized “anti-elite” populism that reproduces old exclusions under new slogans?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: While doing my research, I argued for two key points. First, for Dalit communities in Nepal, there must be total reformation and recognition of the Dalit community. Within the Dalit community itself, there are many different groups, and there is not much unity. To bring them together around their common concerns, there should be recognized group politics. That is why I argued that group politics for the Dalit community should be formally acknowledged by political parties and state institutions.

The second point is redistribution — the redistribution of state resources and state positions, including, for example, land reform and other measures. But even the 2015 Constitution of Nepal did not truly address either redistribution or recognition. Yes, to some extent it recognized Dalit issues, but only superficially.

In terms of representation, because the constitution did not establish a fully proportional electoral system, there is no guarantee of 13% representation for the Dalit community, even though Dalits make up around 13% of the population. In this sense, I always argue that there must be total reformation — one that meaningfully addresses caste discrimination, lack of representation, unemployment, poverty, and related issues. The 2015 Constitution addressed some of these concerns only partially.

The recent uprising and the new process have not specifically addressed caste inequalities or other forms of discrimination. So, I am not very hopeful that the new process — meaning the new election and new parliament — will directly address inequality, since no new constitution is likely to emerge. I don’t know which political parties will return to power or form a government, whether there will be an absolute majority for one party, or whether a youth-led government will emerge. At this stage it is not clear. That is why I am not fully confident that the new process will specifically address caste inequalities or Dalit concerns.

Nepal Risks Sliding Into the Same Disappointments as Sri Lanka and Bangladesh

Lastly, Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya and Bangladesh’s 2024 uprising both toppled governments but slid toward renewed authoritarian populism or elite restoration. What lessons should Nepal’s Gen Z revolution draw from these trajectories if it is to avoid similar cycles of disappointment?

Dr. Mom Bishwakarma: You’re right that the recent examples from Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, as well as other forms of civic resistance in different parts of the world, show that even when there is revolt or resistance against elite authoritarianism, the outcomes are often disappointing. That is exactly what happened in Sri Lanka, in Bangladesh, and in Nepal. The similarities are clear: young people want total reformation, development, and change. That is what the youth in Bangladesh demanded as well, but at the end of the day, the political process did not move in that direction.

In Bangladesh, for instance, there was a revolt against the government, the prime minister fled to India, and a new interim government was installed. Yet elections have still not been held. The same risks exist in Nepal. Here, an interim government was also formed, and young people demanded an independent figure as prime minister. That is why the Chief Justice was appointed as interim prime minister, with a mandate to organize elections by the given deadline. But looking at the current political process, it is not moving in the right direction. Whether elections will even take place on time is uncertain, and many people are openly speculating about delays.

The problem is that dialogue with political parties has not yet begun. At the end of the day, democracy requires political parties to be central stakeholders. Without them, a democratic election cannot be organized. Elections cannot simply be carried out without agreement among the political parties.

For this reason, I am not hopeful that there will be real change, or that the core demands of the Gen Z movement will be addressed either by the interim government or by the new government after elections. Yes, the uprising was a real resistance against elite authoritarianism in Nepal, but the results so far are not heading in a positive direction. The outcome is not what the people of Nepal had hoped for.

I am also not optimistic that the new process will address deeper issues such as caste inequalities or caste-based discrimination. Until and unless the caste system in Nepal is dismantled, discrimination will persist. If there is no new constitution, or at least no specific program aimed at uprooting the caste system, then marginalized groups such as Dalits will continue to face severe discrimination in the future. We will have to wait and see what happens, but at this stage, it remains very unclear what kind of change will come even after new elections in Nepal.