Please cite as:

ECPS Staff. (2026). “Virtual Workshop Series — Session 13: Constructing and Deconstructing the People in Theory and Praxis.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). March 9, 2026. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00144

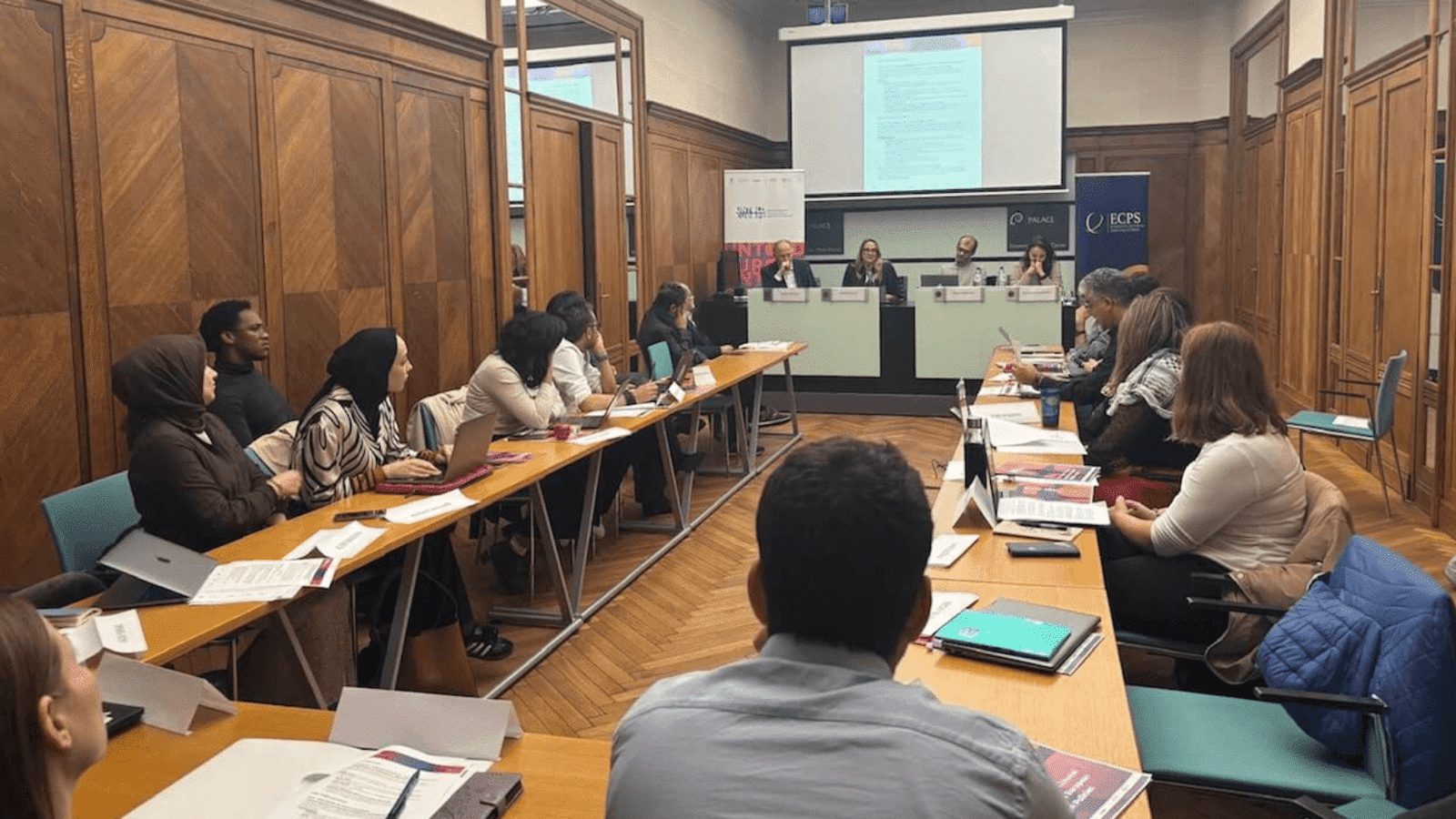

Session 13 of the ECPS Virtual Workshop Series examined how “the people” are constructed, contested, and institutionalized across diverse political arenas. Chaired by Dr. Leila Alieva (Oxford School for Global and Area Studies), the panel brought together interdisciplinary perspectives on populism, democratic participation, and representation. Assistant Professor Jasmin Hasanović analyzed the ethnic dynamics of populist subject formation in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s post-Dayton political order. Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve explored how participants in France’s Yellow Vests movement sought to institutionalize grassroots assembly-based democracy. Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez examined the exclusion of stateless and marginalized communities from international diplomacy, arguing for a “right to diplomacy.” Together, the contributions illuminated the evolving and contested meaning of “the people” in contemporary democratic politics.

Reported by ECPS Staff

On Thursday, March 5, 2026, the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS) convened the thirteenth session of its Virtual Workshop Series, “We, the People” and the Future of Democracy: Interdisciplinary Approaches, under the title “Constructing and Deconstructing the People in Theory and Praxis.” Bringing together scholars from political science, democratic theory, and critical diplomacy studies, the session addressed one of the most urgent questions in contemporary political analysis: how “the people” are imagined, institutionalized, contested, and reconfigured across different political settings. From post-conflict power-sharing arrangements and assembly-based democratic experiments to the exclusions embedded in international diplomacy, the panel examined the shifting boundaries of political representation in a time of democratic strain and institutional transformation.

The participants of the session were introduced by Reka Koleszar, ECPS intern. Chairing the session, Dr. Leila Alieva of the Oxford School for Global and Area Studies framed the discussion as the product of an increasingly mature and sophisticated intellectual agenda within the workshop series. As she observed, by the thirteenth session the series had reached a “quite intricate level of analysis,” with all three presentations deeply interconnected in their exploration of “the genesis, evolution, and formation of populism, and concepts and images related to that.” She underscored the broader strengths of the ECPS project—above all its multidisciplinary, comparative, and constructivist orientation. In a post-Cold War environment marked by uncertainty, complexity, and multiple interacting forces across political, social, and international levels, such a broad approach is particularly necessary. The rise of populism, she suggested, cannot be adequately understood within the limits of a single discipline; rather, it must be approached through the combined lenses of political science, international relations, democratic theory, and broader social inquiry.

Under Dr. Alieva’s chairmanship, the panel featured three speakers whose papers illuminated distinct yet overlapping dimensions of democratic representation. Assistant Professor Jasmin Hasanović (University of Sarajevo) explored the ethnic dynamics of populist subject formation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, offering a new framework for understanding inter-ethnic, intra-ethnic, and cross-ethnic populisms within a post-Dayton consociational order. Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve(Radboud Universiteit; UCLouvain) examined how participants in the Yellow Vests movement in France sought to institutionalize direct democracy through popular assemblies, thereby pushing beyond protest toward constituent democratic experimentation. Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez (UNPO) extended the discussion into the international arena by arguing that diplomatic representation itself must be rethought as a pillar of democracy, especially for unrepresented nations, Indigenous peoples, and politically marginalized communities.

The session also benefited from the incisive engagement of its two discussants, Associate Professor Christopher N. Magno (Gannon University) and Dr. Amedeo Varriale (University of East London). Their interventions not only drew out the conceptual strengths of the presentations but also situated them within wider comparative debates on populism, democratic innovation, sovereignty, and political exclusion. Together, chair, speakers, and discussants produced a rich exchange that revealed both the diversity of contemporary democratic struggles and the common tensions that run through them. As Dr. Alieva noted in her concluding reflections, the discussion demonstrated that populism often functions as a sign of deeper institutional pressure—an indication that inherited political forms are struggling to respond to changing social realities. Session 13 thus offered a compelling interdisciplinary inquiry into how democratic subjects are made, constrained, and reimagined across multiple arenas of political life.

Assist. Prof. Jasmin Hasanović: “Reimagining Populism: Ethnic Dynamics and the Construction of ‘the People’ in Bosnia and Herzegovina”

Assistant Professor Jasmin Hasanović presented a theoretically informed analysis of populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina, proposing a conceptual rethinking of how “the people” are politically constructed within the country’s ethnically structured post-conflict order. Moving beyond dominant interpretations that treat populism as a thin ideology attached to ethno-nationalism, Dr. Hasanović advanced a discursive and relational understanding of populism grounded in Ernesto Laclau’s theoretical framework. His presentation examined how populist logics interact with Bosnia and Herzegovina’s institutionalized ethnic power-sharing system, producing multiple and sometimes contradictory constructions of the political subject known as “the people.”

Dr. Hasanović began by situating the Bosnian political system within its historical and institutional context. The end of the Bosnian war and the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement established a complex power-sharing arrangement among the country’s three dominant ethnic groups—Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs. The agreement institutionalized a consociational structure that translated wartime territorial and political balances into a post-war governance framework characterized by parity, consensus mechanisms, and territorial division into two entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska. This arrangement, while designed to stabilize a deeply divided society, also embedded ethnic identity into the very architecture of political representation and competition.

Within this institutional environment, political life has largely been structured through ethnically segmented arenas. Electoral competition and party organization tend to operate primarily within ethnic constituencies, resulting in parallel political subsystems rather than a fully integrated national political sphere. Existing scholarship, Dr. Hasanović observed, has therefore tended to interpret Bosnian politics through the lenses of ethnic nationalism, power-sharing institutions, or the challenges of democratic consolidation. When populism is discussed, it is frequently conceptualized either as “ethnic populism” or as a thin ideological layer attached to ethno-nationalist politics.

Dr. Hasanović challenged this prevailing approach by proposing that populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina should instead be understood as a political logic that discursively constructs collective political subjectivities. Drawing on Laclau’s conceptualization, he defined populism not by its ideological content but by its form: a discursive strategy that constructs a political frontier between “the people” and an antagonistic order of power. In this perspective, populism does not mobilize a pre-existing people; rather, it actively constructs the people by linking heterogeneous social demands into what Laclau calls a “chain of equivalence.” When one demand temporarily comes to represent a wider set of grievances, it becomes an “empty signifier” capable of symbolically unifying those demands and establishing a political frontier between the people and those perceived as responsible for their grievances.

Building on this theoretical foundation, Dr. Hasanović argued that the ethnicized power-sharing system itself generates populist dynamics by producing persistent unmet political demands across society. Rather than viewing populism as an external threat to democratic institutions, he suggested that populist logics emerge from within the structural tensions of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s post-conflict governance system. In order to capture these dynamics, he identified three interconnected forms of populism operating within the Bosnian political landscape: inter-ethnic populism, intra-ethnic populism, and cross-ethnic populism.

The first and most visible form is inter-ethnic populism, which largely corresponds to what earlier research describes as ethno-nationalist populism. In this configuration, the populist frontier is constructed horizontally across ethnic groups rather than vertically between the people and elites. Political actors mobilize discourses that distinguish “our people” and “our elites” from “their people” and “their elites,” reinforcing antagonism among ethnic communities. Here, the “empty signifier” that unifies social demands is constrained by ethnic identity, meaning that only demands framed through ethnic belonging can enter the chain of equivalence. As a result, the political subject constructed through this form of populism is an ethnicized people whose grievances are directed toward perceived injustices within the constitutional order established after the war. Dr. Hasanović emphasized that ethnicity in this context is not simply a cultural category, but a politically constructed subject formed through populist articulation of dissatisfaction with the post-Dayton system.

The second form, intra-ethnic populism, emerges within the segmented political arenas created by the power-sharing arrangement. According to Dr. Hasanović, because electoral competition takes place largely within monoethnic constituencies, populist rhetoric frequently develops inside ethnic communities rather than across them. In this case, the populist frontier assumes a vertical form, opposing “our people” to “our corrupt elites.” Opposition parties and splinter political movements often deploy such narratives, accusing established ethnic leaders of monopolizing representation, capturing state institutions, and exploiting public resources through clientelistic networks. These actors frame themselves as authentic representatives of the people against entrenched political insiders. Yet despite its vertical orientation, intra-ethnic populism remains bounded by the ethnic framework. The political subject it constructs is still defined ethnically, and the critique of elites does not transcend the segmented structure of the political system.

The third and most fragile form identified by Dr. Hasanović is cross-ethnic populism, which attempts to construct a political subject that transcends ethnic divisions altogether. Unlike the previous forms, cross-ethnic populism articulates the people primarily as citizens rather than members of ethnic groups. It mobilizes grievances that cut across ethnic boundaries, including socio-economic inequality, corruption, demands for justice, and broader calls for institutional accountability. Dr. Hasanović pointed to civic protests, grassroots mobilizations, and civil society initiatives as examples of this form of populism. One illustrative moment occurred during the protests of 2013–2014, when demonstrators adopted the slogan “We are hungry” expressed simultaneously in Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian. By articulating a shared experience of economic hardship across linguistic variations, the slogan attempted to construct a unified citizenry opposed to an unresponsive political establishment.

Despite its emancipatory potential, however, cross-ethnic populism faces significant structural obstacles. Ethno-national elites frequently reinterpret cross-ethnic mobilizations as threats to their respective communities, portraying them as externally driven attempts to undermine group interests. Such reframing disrupts the formation of a durable chain of equivalence capable of unifying heterogeneous demands across the broader population. Consequently, cross-ethnic populist initiatives have struggled to produce a stable and lasting political subject capable of challenging the entrenched ethnopolitical order.

In conclusion, Dr. Hasanović argued that these three forms of populism interact dialectically within Bosnia and Herzegovina’s political system. Inter-ethnic populism reinforces ethnic fragmentation and inadvertently stabilizes the existing power-sharing framework, even when it rhetorically criticizes it. Intra-ethnic populism introduces competition within ethnic communities, challenging the dominance of entrenched elites while remaining confined to monoethnic arenas. Cross-ethnic populism, by contrast, represents an attempt to destabilize the entire hegemonic configuration by constructing a new political subjectivity beyond ethnic identity.

To Dr. Hasanović, these dynamics suggest that populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot be understood simply as a democratic threat or a corrective force. Rather, it operates as a political logic embedded within the structural conditions of a post-conflict power-sharing system. The Dayton constitutional order continuously generates antagonistic frontiers that shape how political actors construct and mobilize “the people.” As Dr. Hasanović emphasized, the concept of the people is never neutral or pre-given; it is always discursively mediated and shaped by the institutional and social dynamics of a particular society. His analysis therefore contributes to a deeper understanding of how populist logics function within divided post-conflict states and how the very meaning of “the people” remains contested, constructed, and continuously renegotiated in political practice.

Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve: “Institutionalizing the Assembled People”

Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve presented a theoretically and empirically grounded exploration of grassroots democratic experimentation under the title “Institutionalizing the Assembled People.” Drawing on research derived from her doctoral dissertation, Dr. Van Outryve examined how ordinary citizens engaged in radical democratic practices during the Yellow Vests movement in France attempted not merely to deliberate collectively but also to institutionalize direct democratic governance. Her analysis offered an important contribution to contemporary debates on democratic theory by investigating how political actors outside formal institutions conceptualize and attempt to institutionalize forms of self-government.

The presentation began by situating the problem historically. For centuries, the processes of instituting democratic systems and making decisions on public affairs have largely been monopolized by professional political elites. Representative institutions, while formally democratic, have tended to concentrate both constitutive and decision-making authority in a specialized political class. Against this background, Dr. Van Outryve advanced the central hypothesis guiding her research: that ordinary citizens are capable not only of deciding on public affairs but also of determining the institutional procedures through which those decisions should be made. This hypothesis challenges the conventional model of democratic innovation, which typically proceeds from top-down reforms initiated by states or policymakers.

Dr. Van Outryve examined this proposition through extensive fieldwork conducted in the town of Commercy in northeastern France during and after the emergence of the Yellow Vests (Gilets Jaunes) movement in 2018. Over the course of two years, she undertook a comprehensive ethnographic study of local democratic practices that developed within the movement. Her research methods included participant observation in assemblies, demonstrations, and meetings; two rounds of interviews conducted before and after the municipal elections of 2020; a collective interview session lasting two days; and the collection of approximately 2,500 documents produced by the movement. Through this combination of qualitative methods, Dr. Van Outryve sought to reconstruct how participants themselves conceptualized and institutionalized their democratic experiment.

The theoretical orientation of the research was articulated through what Dr. Van Outryve termed “inductive political theory.” This approach seeks to bridge normative political theory and empirical research by deriving theoretical insights from the practices and reflections of political actors engaged in real-world democratic experiments. Her doctoral project pursued two parallel objectives: the elaboration of a normative democratic theory based on assembly-based direct democracy—what she refers to as “communist direct democracy,” inspired by the ideas of Murray Bookchin—and the empirical reconstruction of how such democratic practices were attempted by grassroots actors. By allowing participants themselves to address fundamental questions about democracy and self-government, the project aimed to generate a political theory grounded in lived democratic practice.

The empirical core of Dr. Van Outryve’s presentation focused on the case of Commercy, a town of roughly 5,400 inhabitants that became a notable site of democratic experimentation within the Yellow Vests movement. Like many other local groups across France, activists in Commercy initially organized daily assemblies in which participants gathered to deliberate collectively on political grievances and strategies. These assemblies operated according to principles of direct democracy: equality of participation, one person–one vote, and open deliberation without permanent leadership. Instead of formal leaders, the assemblies appointed rotating spokespersons tasked with conveying collective decisions. The assemblies also sought to coordinate with other similar groups, forming confederated networks of local assemblies.

At this early stage, these practices functioned primarily as prefigurative politics—that is, attempts to enact the democratic forms participants wished to see in society at large. However, the trajectory of the Commercy group evolved when some participants decided to contest the municipal elections in March 2020. Their objective, to Dr. Van Outryve, was not to assume traditional representative authority but rather to institutionalize the direct democratic practices that had emerged during the movement. The electoral list they presented proposed to transfer effective political authority to a popular assembly open to the residents of the town. Elected officials would remain formally responsible for administrative tasks, but their mandate would be strictly tied to decisions made by the assembly.

This transition from prefigurative activism to institutional design marked a crucial stage in the movement’s development. During the electoral campaign, participants engaged in what Dr. Van Outryve described as a constituent process, drafting several foundational documents intended to define the institutional architecture of this proposed system. Among these were a local constitution and a commitment charter specifying the relationship between elected officials and the popular assembly. Through this process, participants confronted a series of classical questions in political theory, including the nature of sovereignty, the boundaries of political authority, and the mechanisms through which democratic decisions should be made and revised.

One of the central theoretical dilemmas addressed by the group concerned what Dr. Van Outryve referred to as the “constituent paradox.” This refers to the problem of how a political community decides on the procedures through which it will decide—in other words, how to “decide on how to decide.” Participants grappled with this issue by collectively debating the rules governing deliberation, participation, and decision-making within the assembly. These discussions extended to practical questions such as where assemblies should be held, how information should be shared with the broader population, and how to address the challenges of participation and self-selection among citizens.

The resulting proposals envisioned the assembly as the central locus of political power. The assembly would deliberate on municipal issues, organize specialized commissions, determine decision-making procedures, and supervise the actions of elected representatives. At the same time, participants were acutely aware of the potential risks associated with direct democracy, including the possibility that assemblies might adopt decisions that could be perceived as unjust or undesirable. This concern led to the development of self-limiting institutions designed to regulate the exercise of collective power.

Dr. Van Outryve highlighted this dimension as a particularly significant aspect of the experiment. Drawing inspiration from historical precedents in ancient Greek democracy—particularly the institution of graphe paranomon, which allowed citizens to challenge laws adopted by the assembly—participants devised mechanisms through which decisions could be reviewed. One such mechanism involved the creation of a Citizens’ Constitutional Council, whose members would be selected by lot. This body would examine whether decisions taken by the assembly were compatible with the principles articulated in the preamble of the local constitution. If a decision were found inconsistent with these principles, it would be returned to the assembly for reconsideration.

Importantly, the safeguards envisioned by participants were not intended to constrain democratic debate or impose ideological boundaries on the assembly. Rather, they reflected a commitment to what Dr. Van Outryve described as the democratization of dissensus. Participants explicitly rejected the idea that assemblies should strive for unanimity or suppress political disagreement. Instead, they emphasized that conflict and disagreement are inherent features of democratic politics and should be managed collectively by citizens rather than monopolized by party competition within representative institutions.

This perspective also shaped their understanding of political neutrality and partisanship. While the movement sought to remain non-partisan and unaffiliated with established political parties, this stance did not imply the absence of political conflict. On the contrary, participants insisted that assemblies must remain open spaces where diverse viewpoints could be expressed and debated. The aim was therefore not to eliminate disagreement but to create institutional conditions in which political conflict could be deliberated among citizens themselves.

Throughout the presentation, Dr. Van Outryve underscored that the Commercy experiment represented a broader attempt to rethink foundational concepts in democratic theory through lived political practice. Participants revisited questions concerning representation, deliberation, participation, and constitutional authority, seeking to rearticulate them within a framework centered on assemblies rather than elected representatives. In doing so, they attempted to move beyond a model of democracy based primarily on consent to authority toward one in which citizens collectively exercise political power.

In concluding, Dr. Van Outryve emphasized that the creation of democratic institutions enabling widespread participation cannot be designed solely by theorists or political elites. Echoing the reflections of Cornelius Castoriadis, she argued that the development of non-alienating forms of democracy must ultimately emerge from the collective creativity and practical experimentation of the people themselves. The Commercy assemblies thus illustrate how grassroots movements can contribute to democratic theory by demonstrating that citizens are capable not only of governing themselves but also of collectively determining the institutional frameworks through which self-government may be realized.

Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez: “Re-imagining Diplomatic Representation as a Pillar of Democracy”

Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez presented an ambitious and conceptually rich paper that examined democratization from a diplomatic perspective. Her presentation, “Re-imagining Diplomatic Representation as a Pillar of Democracy,”proposed that diplomacy should not be understood merely as a technical instrument of interstate relations, but as a normative and institutional domain deeply implicated in the realization—or denial—of democratic participation. In doing so, she shifted the discussion of democracy beyond domestic institutions and electoral representation toward the international arena, where questions of voice, visibility, recognition, and participation remain profoundly unequal.

The central argument of the presentation was that the exclusion of unrepresented nations, Indigenous peoples, minority communities, and non-sovereign political actors from meaningful diplomatic engagement constitutes a structural failure of democratic governance at both national and international levels. Drawing on critical and post-positivist approaches to diplomacy, Cancela Sánchez argued that diplomatic representation should be regarded as a foundational pillar of democracy rather than as an external or secondary concern. Her intervention therefore sought to expand the conceptual boundaries of democracy by foregrounding the institutions and practices through which political communities seek recognition, negotiate their futures, and participate in decisions that affect their lives.

The presentation opened with a reflection on the well-known phrase that begins the United Nations Charter: “We the Peoples of the United Nations.” This rhetorical commitment to peoples rather than merely states served as a point of departure for a critical inquiry into the actual functioning of multilateral diplomacy. Cancela Sánchez asked to what extent contemporary diplomatic institutions live up to this promise. While diplomacy has undoubtedly changed over recent decades—with broader issue agendas, the increasing involvement of multiple governmental and non-governmental actors, and expanding forums for participation—she emphasized that these developments have not eliminated the deep inequalities that shape access to diplomatic representation. Spaces of participation may have widened, but they remain uneven, contested, and structurally constrained.

A key contribution of the presentation lay in its conceptual discussion of diplomacy itself. Cancela Sánchez traced an evolution from classical, state-centric definitions toward broader and more socially embedded understandings. Traditional definitions present diplomacy as the conduct of business between states or as communication through official channels in a system of states. By contrast, post-positivist scholars have redefined diplomacy as a practice of representation structured through institutions and processes that manage relations among human beings more broadly. Particularly important for her argument was the idea that diplomats, like elected representatives, function as agents entrusted by principals. This analogy enabled her to draw a direct conceptual link between diplomatic representation and representative democracy.

On this basis, Cancela Sánchez explored the nexus between democracy and diplomacy. Although the two may pursue different immediate objectives—democracy oriented toward equality and freedom, diplomacy toward the peaceful advancement of interests—they nevertheless share important underlying principles, including participation, negotiation, representation, and cooperation. The question, then, is whether diplomacy can genuinely claim democratic legitimacy if it fails to reflect the full diversity of those in whose name it operates. Her answer was clearly negative: where entire peoples are denied meaningful access to diplomatic arenas, democracy is compromised at its foundations.

The presentation further argued that the absence of diplomatic representation has serious normative and legal consequences. Exclusion from diplomatic spaces silences communities in settings where decisions affecting their future are made. This, Cancela Sánchez suggested, compounds violations already recognized in international legal instruments concerning civil and political rights, Indigenous rights, labor rights, and participation. Such exclusions thus cannot be dismissed as procedural oversights; they represent systematic denials of political agency. In response, she drew on the recently developed concept of the right to diplomacy, which provides the normative framework for her analysis.

As presented by Cancela Sánchez, the right to diplomacy goes beyond mere presence or symbolic inclusion in international forums. It requires meaningful participation, including the right to be consulted, to negotiate, to provide free, prior, and informed consent, and to contribute to shaping the legal and institutional arrangements that govern one’s community. This framework challenges the hierarchical, state-centered organization of diplomacy by insisting that actors beyond sovereign states possess legitimate claims to diplomatic agency. Democratizing diplomacy, in this view, requires both normative and institutional transformation.

To illustrate the practical relevance of this argument, Cancela Sánchez examined the case of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO), founded in 1991 to address the exclusion created by the formal requirement of recognized statehood for participation in international decision-making. UNPO, she argued, functions as an institutional workaround that enables unrepresented peoples and minority communities to engage international institutions, gain visibility, and mediate relationships with the broader international community. Yet it also reveals the limits of informal or substitute forms of representation when access to binding diplomatic power remains restricted.

Her first case study, Tibet, demonstrated the constraints of diplomatic action without sovereignty. The Tibetan government in exile has created institutional structures resembling a foreign ministry and established offices abroad to represent Tibetan interests. Tibetan representatives have engaged in negotiations and have, in some cases, received forms of ambassadorial recognition. Yet these interactions remain fundamentally precarious and unofficial. Governments may engage Tibet informally while avoiding formal recognition of its right to diplomatic participation. As Cancela Sánchez showed, Tibet’s diplomatic efforts therefore remain confined to the margins, illustrating the profound limitations imposed by the denial of formal standing.

The second case, East Timor, offered a contrasting example of what diplomatic representation can achieve when political space is opened. During the Indonesian occupation, East Timorese representatives used platforms such as UNPO to sustain international visibility, engage foreign governments and civil society, and keep humanitarian concerns on the global agenda. This sustained diplomatic representation contributed to the eventual conditions under which the East Timorese people could participate in a UN-supervised referendum in 1999. For Cancela Sánchez, East Timor demonstrated that diplomatic representation can make politically visible what would otherwise remain excluded from international negotiation and resolution.

The third case, the Chamorro people of Guam, revealed the paradoxes of disenfranchisement within a formal democratic order. Although Chamorro people are citizens of the United States, they lack full political representation within the institutions that govern them. At the same time, their appeals to international institutions regarding military expansion, decolonization, and cultural survival have encountered resistance. Through Guam, Cancela Sánchez underscored that diplomatic exclusion is not limited to non-state peoples external to democratic states; it can also affect communities formally located within them.

In conclusion, the presentation argued that exclusion from diplomatic spaces is a structural and democratic problem with far-reaching implications for self-determination, human rights, and cultural survival. While organizations such as UNPO provide valuable frameworks for advocacy and visibility, they cannot substitute for full diplomatic standing. Cancela Sánchez therefore called for a rethinking of both democracy and diplomacy, insisting that meaningful diplomatic participation should be recognized as a democratic right of all peoples. Her presentation made a compelling case that democratizing diplomacy is not peripheral to democratic theory but essential to any serious account of inclusive political representation in a deeply unequal international order.

Discussants’ Feedback

Feedback by Assoc. Prof. Christopher Magno

Serving as discussant for Session 13 of the ECPS Virtual Workshop Series, Associate Professor Christopher Magno offered a series of reflections and critical questions engaging with the three presentations delivered in the panel. His comments highlighted the conceptual contributions of the papers while situating them within broader debates on populism, democratic innovation, and diplomatic representation. Rather than offering extensive critique, Assoc. Prof. Magno focused on identifying key analytical insights and raising questions that could further develop the presenters’ arguments.

Assoc. Prof. Magno began with a brief summary of Dr. Jasmin Hasanović’s presentation on populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He noted that the paper addressed an important puzzle: how populism operates in a post-conflict society where politics is already structured around ethnic power-sharing arrangements. Unlike many studies of populism that focus on Western democracies and conceptualize populism primarily as a vertical conflict between “the people” and political elites, Bosnia presents a distinct configuration in which political competition is embedded within a tri-ethnic institutional framework. Assoc. Prof. Magno highlighted Dr. Hasanović’s typology of inter-ethnic, intra-ethnic, and cross-ethnic populism as a useful analytical framework for understanding these dynamics. In this context, populism does not appear as a singular political logic but as a multi-layered phenomenon shaped by ethnic competition between groups, political rivalry within groups, and occasional civic mobilization across ethnic boundaries.

Expanding on this point, Assoc. Prof. Magno emphasized that inter-ethnic populism remains the dominant form in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as political actors often frame politics as a struggle between ethnic communities. Political elites mobilize historical grievances, wartime memories, and narratives of collective threat in order to maintain political support. In contrast, intra-ethnic populism introduces competition within ethnic communities by challenging the authority of established leaders and accusing them of corruption or betrayal. Cross-ethnic populism, while comparatively weaker, attempts to articulate common socio-economic grievances—such as unemployment, corruption, and inequality—across ethnic divisions. However, Assoc. Prof. Magno observed that the institutional structure of the Bosnian political system continually redirects political competition back into ethnic categories, thereby constraining the development of broader civic mobilization.

Building on Dr. Hasanović’s framework, Assoc. Prof. Magno proposed an additional analogy drawn from contemporary digital politics. He suggested that similar dialectical dynamics of identity formation can be observed in online communities shaped by algorithmic sorting and psychographic profiling. Social media platforms often cluster users into identity-based networks that reinforce shared narratives and ideological affinities. Within these networks, horizontal conflicts between different online “tribes” mirror the dynamics of inter-group populism, while internal disputes between members and community leaders resemble intra-group populist tensions. Although presented as an illustrative parallel rather than a direct theoretical claim, this observation pointed toward possible connections between identity-driven populism and digitally mediated political environments.

Assoc. Prof. Magno then turned to Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve’s presentation on the institutionalization of popular assemblies emerging from the Yellow Vests movement in France. He framed the paper around a central question: whether grassroots democratic practices can be transformed into durable governing institutions. The case of the Commercy citizens’ assembly, he noted, represents an attempt not merely to protest representative democracy but to construct an alternative institutional model grounded in direct citizen participation. By drafting a local constitution and designing institutional mechanisms linking elected officials to the citizens’ assembly, participants effectively acted as a constituent power seeking to redefine how political authority should be exercised.

In discussing the analytical contribution of the paper, Assoc. Prof. Magno identified three central challenges associated with institutionalizing assembly-based democracy. The first concerns the boundaries of political participation—that is, who constitutes “the people” in such assemblies. While the Commercy model opened participation to all residents, voluntary participation raises questions about representativeness and the risk of self-selection bias. The second challenge relates to deliberative procedures. Assemblies initially served as spaces for expressing grievances but gradually evolved into arenas for collective deliberation in which preferences could be revised through discussion. Assoc. Prof. Magno connected this process to broader theories of deliberative democracy, including the idea of the public sphere as a space where citizens transform private concerns into collectively debated public issues. The third challenge involves the limits of power, particularly the tension between radical democratic experimentation and the existing institutional framework of representative government. Even when assemblies claim political authority, they must operate within established legal and electoral systems, raising questions about whether such initiatives can transform existing institutions or whether they will ultimately be absorbed by them.

Finally, Assoc. Prof. Magno briefly addressed the presentation by Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez on diplomatic representation and the “right to diplomacy.” He highlighted the paper’s effort to rethink the relationship between diplomacy and democracy by questioning whether state diplomacy genuinely reflects the diverse populations it claims to represent. In democratic theory, diplomacy is often assumed to aggregate the will of a population through state representation. Yet in practice, Assoc. Prof. Magno noted, states frequently operate as strategic actors pursuing national interests rather than consultative representatives of internal constituencies. This tension, he suggested, creates a gap between a consultative model of diplomatic representation and a sovereignty-driven model in which governments act autonomously in international negotiations. The “right to diplomacy” framework discussed in the presentation seeks to address this gap by proposing that communities inadequately represented by states—including Indigenous peoples and non-self-governing territories—should gain more direct or mediated access to diplomatic platforms.

Across his remarks, Assoc. Prof. Magno concluded by posing several questions intended to stimulate further discussion among the presenters. These included whether populism might strengthen democratic participation under certain conditions, whether assembly democracy can realistically function as a governing system, and how diplomatic representation might be reimagined to better reflect the voices of marginalized communities. Through these interventions, his commentary framed the session as a broader exploration of how “the people” are constructed, represented, and institutionalized across different political arenas—from post-conflict societies and grassroots democratic movements to the structures of international diplomacy.

Feedback by Dr. Amedeo Varriale

Serving as second discussant for Session 13, Dr. Amedeo Varriale offered thoughtful reflections on the three presentations delivered during the panel. His commentary emphasized the analytical contributions of the papers while situating them within broader comparative debates on populism, democratic experimentation, and diplomatic representation. Drawing on his own comparative research on political ideology and populism, Dr. Varriale focused particularly on the conceptual frameworks advanced by the presenters and their potential applicability beyond the specific cases examined.

Dr. Varriale began by addressing Dr. Jasmin Hasanović’s presentation on populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He commended the paper’s effort to conceptualize populism within the context of a post-Dayton political system characterized by externally imposed power-sharing institutions and deeply entrenched ethnic divisions. In his view, the principal strength of the work lies in its proposed typology distinguishing inter-ethnic, intra-ethnic, and cross-ethnic populisms. This categorization, he argued, provides a useful analytical framework for understanding how populist mobilization operates in Bosnia’s consociational political environment.

Beyond its immediate empirical application, Dr. Varriale emphasized the broader analytical value of the typology. He suggested that these categories possess considerable “travelability,” enabling scholars to apply them to different political contexts outside the Balkans. For example, he noted that dynamics resembling inter-ethnic populism can be observed in cases where political actors mobilize territorial or cultural divisions within a state. He pointed to early iterations of the Northern League in Italy as a case in which political mobilization drew upon regional divisions between northern and southern Italians while simultaneously employing anti-elitist rhetoric.

Similarly, the concept of intra-ethnic populism resonated, in his view, with developments associated with several left-wing populist movements across Europe. Parties such as the Five Star Movement in Italy, Podemos in Spain, and Syriza in Greece have often framed their political discourse in terms of reclaiming democratic power from corrupt or detached elites and returning agency to ordinary citizens. In such cases, populist rhetoric may contribute to enhancing political participation by giving voice to constituencies that perceive themselves as excluded from established decision-making processes. Cross-ethnic populism, although less common, can also appear in transnational or supra-national initiatives that attempt to mobilize citizens across national boundaries, such as the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 associated with Yanis Varoufakis.

While praising the conceptual innovation of Dr. Hasanović’s framework, Dr. Varriale also raised a question regarding the relative weight of populism in certain Bosnian political parties. Specifically, he wondered whether some parties often categorized as populist might more accurately be understood primarily as ethno-nationalist formations that employ populist rhetoric instrumentally. Parties such as the Serb Democratic Party (SDS), the Party of Democratic Action (SDA), and the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) may rely heavily on ethnonationalist narratives, with populism functioning as a secondary strategic component rather than the core ideological element. This observation, he suggested, may represent a fruitful avenue for further reflection within the broader theoretical framework proposed in the paper.

Turning to the presentation by Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve on the institutionalization of assembly-based democracy emerging from the Yellow Vests movement in France, Dr. Varriale highlighted the paper’s relevance for understanding contemporary debates about democratic participation. At a time when representative democratic institutions are often perceived as increasingly detached from ordinary citizens, the case examined in the paper illustrates how grassroots movements attempt to operationalize alternative democratic forms at the local level.

Dr. Varriale emphasized that one of the principal contributions of the research lies in its detailed reconstruction of how direct democratic practices can be translated into institutional arrangements. While the concept of direct democracy is well known in theoretical discussions, empirical studies examining its practical implementation remain comparatively rare. In this respect, the paper’s analysis of the Citizens’ Assembly in Commercy provides valuable insights into the institutional design, deliberative processes, and practical challenges associated with such democratic experiments. In particular, he noted that the tensions described between the Citizens’ Assembly and the municipal council illustrate a long-standing theoretical dilemma: the coexistence—and often conflict—between radical forms of direct democracy and the institutional structures of representative liberal democracy.

Dr. Varriale also observed several parallels between the democratic practices described in the paper and developments associated with European left-wing populist movements. Mechanisms such as imperative mandates, the principle of one person–one vote, and participatory decision-making processes resemble organizational features adopted by parties such as Italy’s Five Star Movement. These parallels suggest that contemporary movements seeking to revitalize democratic participation frequently converge around similar institutional innovations, even when operating in distinct political contexts.

While commending the sophistication of the theoretical and methodological framework—particularly the extensive fieldwork underpinning the study— Dr. Varriale suggested that future research might further situate the case within the broader political context of France. Additional discussion of the political conditions that facilitated the emergence of the Yellow Vests movement, as well as the reactions of state institutions, could enrich the analysis. Nevertheless, he emphasized that the paper successfully demonstrates how social movements can function as laboratories for democratic experimentation.

Finally, Dr. Varriale addressed the presentation by Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez on diplomatic representation and the “right to diplomacy.” He noted that the case studies presented—Tibet, Timor-Leste, and Guam—highlight different forms of political exclusion within the contemporary international order. The example of Guam, in particular, drew his attention as a striking illustration of democratic contradiction within an established democratic state. Despite holding US citizenship, residents of Guam lack voting representation in Congress and cannot participate in presidential elections, revealing a gap between democratic principles and constitutional structures.

Dr. Varriale observed that among the cases examined, Timor-Leste represents the most evident example of diplomatic success, as international engagement ultimately culminated in a referendum enabling self-determination. This outcome illustrates how diplomatic advocacy and international visibility can, under certain conditions, contribute to political transformation.

Concluding his remarks, Dr. Varriale reflected on the tension between sovereignty and democratic inclusion in international diplomacy. Sovereignty, he noted, provides a framework of order and legitimacy that structures diplomatic relations among states. Yet, at the same time, the formal authority associated with sovereignty may obscure the political voices of communities that lack recognized statehood. The challenge, therefore, lies in reconciling the stability provided by the sovereign state system with the normative imperative to expand political voice and representation within international decision-making processes.

Responses

Response by Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez

In her brief response to the discussants’ remarks, Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez elaborated on several aspects of her research concerning diplomatic representation and the “right to diplomacy,” while clarifying the broader scope of her study beyond the case studies presented during the session.

Cancela Sánchez first addressed comments regarding the role of the UNPO. She emphasized that the examples discussed in her presentation represent only a small portion of the organization’s broader membership and historical trajectory. Over the years, UNPO has included communities with diverse political aspirations, ranging from groups seeking full statehood to those primarily concerned with securing recognition, representation, and voice in international decision-making processes. In some cases, UNPO has served as a platform through which political entities later achieved internationally recognized statehood. Estonia and Latvia, for example, were once members before eventually becoming sovereign states. These trajectories demonstrate that UNPO can function both as a diplomatic platform for stateless nations and as a transitional space within broader processes of political recognition.

At the same time, Cancela Sánchez stressed that not all members pursue independence. For many communities—such as the Chamorro people of Guam—the central objective is not statehood but meaningful political representation and the ability to articulate their interests in national and international arenas. Such cases illustrate the diversity of political claims that exist beyond the state-centered diplomatic order.

Responding further to methodological questions, Cancela Sánchez clarified that the “right to diplomacy” framework, developed by Costas Constantinou and Fiona McConnell in 2023, forms the conceptual foundation of her research. This framework builds on post-positivist and critical approaches to diplomacy, seeking to rethink diplomatic practice by emphasizing the representation of peoples rather than exclusively sovereign states. As she noted, the framework is still relatively recent, and ongoing research—including her own work—aims to contribute to its further theoretical and empirical development.

Finally, Cancela Sánchez briefly addressed the broader structural context of international diplomacy. Contemporary diplomatic institutions remain fundamentally state-centered, and even the limited mechanisms created to include non-state actors often impose significant barriers to meaningful participation. Forums such as ECOSOC consultative mechanisms, the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and the UN Forum on Minority Issues provide important avenues for engagement, yet they remain uneven and insufficient to guarantee direct diplomatic representation for all affected communities. Her research therefore seeks to highlight these structural limitations while exploring pathways toward a more inclusive and representative diplomatic order.

Response by Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve

In her response to the discussants’ remarks, Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve elaborated on several conceptual and practical issues raised during the discussion of her paper on the institutionalization of assembly-based democracy emerging from the Yellow Vests movement in France. Her reflections focused primarily on the questions of participation, institutional feasibility, and the democratic risks associated with direct forms of governance.

Addressing first the issue of participation, Dr. Van Outryve acknowledged that the legitimacy of an assembly-based democratic system fundamentally depends on sustained citizen involvement. If only a small number of participants attend assemblies, the democratic claim of such institutions would be weakened. However, she emphasized that participants in the Commercy experiment did not conceptualize participation merely in numerical terms or as a short-term challenge. Rather, they viewed it as a long-term political process. According to this perspective, meaningful participation becomes more likely when citizens perceive that their deliberations have real political consequences. In contrast, participatory initiatives that lack decision-making authority often experience declining engagement over time.

Dr. Van Outryve illustrated this dynamic by referring to the French Citizens’ Climate Convention, which demonstrated the capacity of ordinary citizens to deliberate effectively but ultimately saw several of its proposals set aside by the government. For activists in Commercy, such outcomes underscored the importance of granting assemblies genuine decision-making power. When citizens recognize that their contributions directly influence policy outcomes, the motivation to participate is expected to increase. Empirical experiences from nearby municipalities experimenting with similar institutional models suggest that high levels of engagement are possible. In one neighboring locality where participatory institutions were introduced, approximately half of the population attended assemblies, indicating that even non-activist residents may become involved when participatory mechanisms are institutionalized.

Dr. Van Outryve further explained that the solutions proposed by activists to address participation barriers emerged directly from their practical experiences during the Yellow Vests mobilization. Recognizing the social constraints faced by working-class participants—such as irregular work schedules, family responsibilities, and limited free time—the movement explored various institutional adaptations. These included organizing multiple assemblies on the same topic at different times, creating mechanisms to synthesize and circulate deliberative arguments across meetings, and allowing citizens to vote either in person or through accessible channels. Additional measures such as childcare services, transportation assistance, and flexible meeting schedules were also considered to facilitate broader participation.

Another institutional mechanism designed to compensate for potential low attendance was the introduction of a local citizens’ referendum. Under this arrangement, if a specified portion of the electorate—approximately ten percent—challenged a decision adopted by the assembly, the issue could be referred to a broader vote. This mechanism aimed to ensure that decisions retained broader democratic legitimacy even when participation in assemblies fluctuated.

Turning to the broader question of whether assembly-based democracy could realistically function as a governing system, Dr. Van Outryve acknowledged that significant structural obstacles currently exist. Assemblies attempting to exercise political authority must operate within the framework of representative institutions that continue to dominate contemporary political systems. Nevertheless, she emphasized that the long-term strategy envisioned by participants extends beyond isolated municipal experiments. Inspired by traditions of communalist political theory, activists envisioned a network of self-governed municipalities confederated through delegated and recallable mandates. Such a configuration would create a form of dual power between existing state institutions and a confederation of locally governed communes.

Dr. Van Outryve also noted that similar governance structures have been attempted in other contexts, citing the example of the Kurdish political experiment in Rojava as an illustration of how assembly-based forms of governance can operate at larger territorial scales under particular historical conditions. However, she acknowledged that the pathways leading to such transformations differ significantly depending on political context.

Finally, responding to concerns about the potential risks associated with direct democracy—including the possibility of authoritarian or exclusionary outcomes—Dr. Van Outryve emphasized the central role that deliberation plays in the democratic vision articulated by participants in Commercy. For activists involved in the movement, collective deliberation is not simply a procedural step but a transformative political practice capable of reshaping citizens’ perspectives. Their experiences during the Yellow Vests mobilization reinforced the belief that sustained dialogue among citizens can challenge entrenched political divisions and foster mutual understanding.

In this sense, the Commercy experiment reflects a broader conviction that democratic renewal may depend not only on institutional reform but also on the creation of participatory spaces in which citizens engage directly with one another in the ongoing process of collective self-government.

Response by Dr. Jasmin Hasanović

In his response to the discussants’ comments, Dr. Jasmin Hasanović elaborated on several conceptual aspects of his framework for analyzing populism in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Addressing questions raised by the discussants, he clarified both the theoretical foundations of his argument and the structural conditions that shape the forms of populism observed in the country’s post-conflict political order.

Dr. Hasanović began by reflecting on the broader question of whether populism inherently deepens political division. In his view, political division should not be regarded as an anomaly but rather as an intrinsic feature of political life. From this perspective, populism does not generate social antagonisms ex nihilo; rather, it operates as a political logic that articulates and organizes existing tensions within society. Drawing on a discursive approach inspired by Ernesto Laclau, Dr. Hasanović emphasized that populism links disparate grievances into a chain of equivalence through which a political subject—the people—is constructed in opposition to a perceived adversary.

Within the Bosnian context, however, the construction of “the people” has been profoundly shaped by the institutional architecture established after the Dayton Peace Agreement. According to Dr. Hasanović, the consociational power-sharing arrangement effectively replaced a civic conception of sovereignty with an ethnically structured system of political representation. Instead of the demos functioning as the primary bearer of sovereignty, political subjectivity has largely been organized around ethnically defined collectivities. In this sense, Bosnia and Herzegovina operates less as a conventional liberal democracy than as an ethnocratic system in which ethnic identity constitutes the central axis of political competition.

This institutional configuration helps explain why inter-ethnic populism remains more prominent than cross-ethnic forms of mobilization. Political actors frequently construct antagonistic narratives that position one ethnic community against others, thereby reinforcing horizontal divisions within society. Dr. Hasanović noted that such dynamics cannot be understood independently of the broader institutional and territorial arrangements established after the war. The country’s administrative divisions, including the highly autonomous entities of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska, correspond largely to ethnically homogeneous territories that emerged through wartime processes of ethnic cleansing and displacement.

Furthermore, the logic of consociational democracy itself reinforces ethnic segmentation. As theorized by Arend Lijphart, such systems grant ethnic groups significant autonomy in matters considered central to their identity, including cultural, linguistic, and religious affairs. While intended as mechanisms of conflict management, these institutional arrangements also contribute to the entrenchment of ethnic political identities. Over time, the ethnic principle has extended beyond representation to shape broader patterns of social and political life, producing what Dr. Hasanović described as a deeply pillarized society.

Within this framework, Dr. Hasanović also addressed the question raised by discussants regarding the relationship between populism and ethnonationalist parties in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Rather than treating populism as a fixed ideological label, he proposed understanding it as a political logic through which actors construct antagonistic boundaries. From this perspective, ethnonationalist parties may employ populist discourse when mobilizing their constituencies against perceived adversaries, even if ethnonationalism remains their primary ideological foundation.

Given these structural constraints, Dr. Hasanović suggested that the most realistic arena for democratic transformation may lie within intra-ethnic political competition. In the current institutional setting, political contestation largely unfolds within ethnically segmented party systems. Strengthening pluralism and ideological differentiation within these arenas could create conditions for more substantive democratic competition. Over time, the emergence of ideologically convergent actors across different ethnic constituencies might facilitate more cooperative forms of power-sharing and potentially open space for broader cross-ethnic political projects.

In this sense, Dr. Hasanović concluded that the reconstruction of “the people” as a democratic political subject remains a central challenge in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Expanding pluralism within existing political arenas may represent an incremental pathway through which more inclusive forms of democratic politics could eventually emerge.

Closing Remarks by Dr. Leila Alieva

In her closing remarks, Dr. Leila Alieva reflected on the key themes and insights that emerged from the thirteenth session of the ECPS Virtual Workshop Series. She expressed appreciation to the presenters, discussants, and audience for what she described as a rich and intellectually stimulating discussion that not only addressed important questions but also generated new avenues for inquiry.

Dr. Alieva emphasized that the presentations collectively highlighted populism as a broader political signal—an indicator of underlying tensions and contradictions within contemporary political systems. In this sense, populism can be understood as a symptom of institutional arrangements that increasingly lag behind evolving societal, political, and economic dynamics. The session’s contributions illustrated how such pressures often manifest through contested relationships between society, political actors, and institutional frameworks.

Reflecting on the individual presentations, Dr. Alieva noted how Dr. Jasmin Hasanović’s analysis illuminated the enduring influence of institutional legacies in shaping the construction of “the people” within post-conflict political systems. Similarly, the work presented by Dr. Sixtine Van Outryve shed light on tensions between different models of democracy, particularly the contrast between established representative institutions and emerging participatory practices through grassroots assemblies. These dynamics illustrated how societies may attempt to compensate for perceived institutional shortcomings by experimenting with alternative forms of democratic organization.

Dr. Alieva also highlighted the importance of the comparative perspective raised during the discussion. As noted by the discussants, examining cases across different regions—from Eastern and Western Europe to post-Soviet contexts—revealed both shared patterns and distinctive trajectories in the relationship between populism, democracy, and institutional change. Finally, she underscored the significance of Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez’s contribution, which addressed the often-overlooked question of representation and inclusion within diplomatic institutions.

Conclusion

Session 13 of the ECPS Virtual Workshop Series offered an interdisciplinary exploration of how “the people” are constructed, contested, and institutionalized across diverse political contexts. By examining cases that ranged from Bosnia and Herzegovina’s post-conflict constitutional order to grassroots democratic experimentation in France and the diplomatic marginalization of stateless or underrepresented communities, the panel illuminated the multiple arenas in which the meaning of popular sovereignty is negotiated. Collectively, the presentations demonstrated that “the people” is neither a stable nor a self-evident political category; rather, it is continuously shaped through institutional arrangements, political struggles, and discursive practices.

The discussions also revealed a shared analytical thread across the three papers: the recognition that contemporary democratic tensions often arise from mismatches between evolving social demands and the institutional frameworks designed to represent them. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the institutionalization of ethnic power-sharing structures constrains the formation of broader civic political subjects. In the French case, grassroots assemblies reflect citizens’ attempts to reclaim agency in the face of perceived distance between representatives and the represented. In the international arena, the exclusion of unrepresented peoples from diplomatic participation exposes structural limitations within a state-centered global order that formally invokes “the peoples” while largely privileging sovereign states.

In sum, the session underscored that debates about populism, democratic participation, and representation cannot be confined to a single institutional domain. Instead, they span local, national, and international levels, revealing interconnected struggles over voice, legitimacy, and political inclusion. By bringing these diverse perspectives into dialogue, Session 13 contributed to a deeper understanding of the dynamic processes through which democratic subjects are formed and contested. In doing so, it reinforced the broader aim of the ECPS workshop series: to provide an interdisciplinary platform for critically examining the evolving meanings of democracy and “the people” in a rapidly changing political world.