Please cite as:

ECPS Staff. (2025). “ECPS Conference 2025 / Panel 5 — Governing the ‘People’: Divided Nations.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). July 9, 2025. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00111

Panel V of the ECPS Conference 2025, “Governing the ‘People’: Divided Nations,” held on July 2 at St Cross College, University of Oxford, explored how contested constructions of “the people” are shaped by populist discourse across national, religious, and ideological contexts. Co-chaired by Dr. Leila Alieva and Professor Karen Horn, the session featured presentations by Natalie Schwabl (Sorbonne University), Dr. Sarah Riccardi-Swartz (Northeastern University), and Petar S. Ćurčić (Institute of European Studies, Belgrade). The panel examined Catholic nationalism in Croatia, American Christian ethno-populism, and the evolving German left, offering sharp insights into the manipulation of collective identity and memory in populist projects. Bridging multiple regions and disciplines, the panel revealed populism’s capacity to reframe belonging in deeply exclusionary and globally resonant ways.

Reported by ECPS Staff

Panel V of the ECPS Conference 2025, titled Governing the ‘People’: Divided Nations, convened on July 2, 2025 at St Cross College, Oxford, under the overarching theme of “We, the People” and the Future of Democracy: Interdisciplinary Approaches. This intellectually charged session examined the fractured and contested constructions of “the people” across varied historical, cultural, and political contexts, focusing particularly on how populist discourse navigates religious identity, memory politics, and socio-political polarization.

Co-chaired by Dr. Leila Alieva (Associate Researcher, Russian and East European Studies, Oxford School of Global and Area Studies) and Professor Karen Horn (Professor of Economic Thought, University of Erfurt), the session benefitted from their combined expertise in post-Soviet transformation, democratic theory, and political economy. Dr. Alieva welcomed the audience by underlining the significance of case-driven approaches to dissecting populism’s conceptual ambiguity and real-world diversity.

The panel featured three analytically rigorous and empirically rich presentations. Natalie Schwabl (Sorbonne University) opened with a diachronic analysis of Catholic nationalism in Croatia, demonstrating how the term Hrvatski narod has been sacralized, politicized, and manipulated by state and ecclesiastical actors from the Ustaša period through post-socialist independence. Sarah Riccardi-Swartz (Northeastern University) followed with a provocative ethnographic account of American far-right Christian nationalism, highlighting transnational alignments between U.S. Orthodox converts and Russian illiberalism. Finally, Petar S. Ćurčić (Institute of European Studies, Belgrade) offered a comparative analysis of Die Linke and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance in Germany, interrogating whether a coherent form of left-wing populism is still viable amid competing ideological pressures and electoral challenges.

Under the guidance of the co-chairs, the session provided a vibrant space for critical reflection and scholarly dialogue. The panel’s breadth of focus—from Southeastern Europe to the US and Germany—underscored the global entanglements of populist discourse and the enduring power of identity politics in shaping both democratic crisis and populist resurgence.

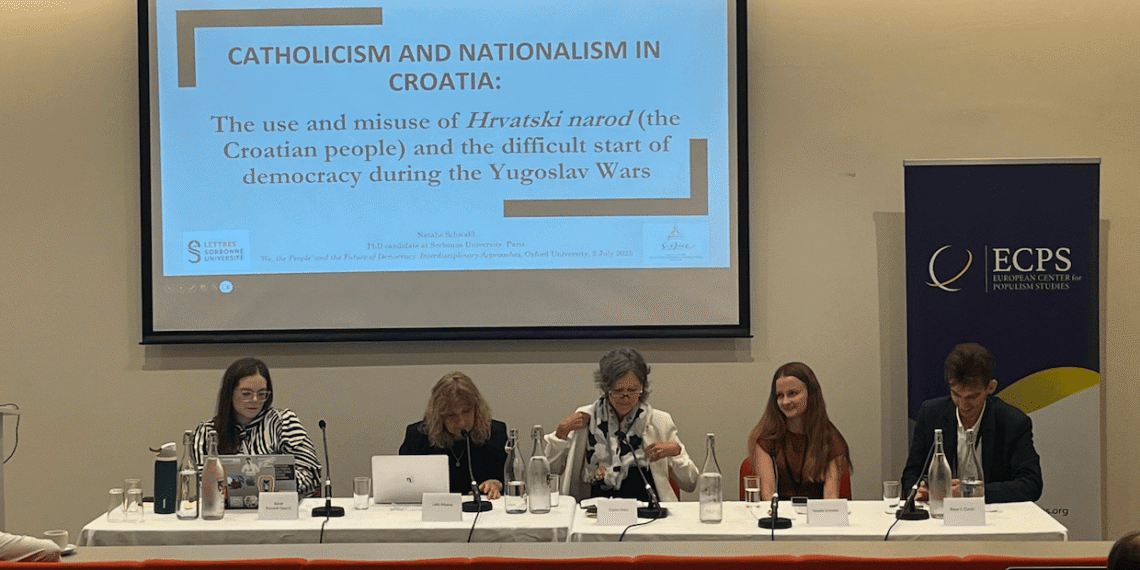

Natalie Schwabl: Catholicism and Nationalism in Croatia: The Use and Misuse of ‘Hrvatski Narod’

In her historically grounded and analytically incisive presentation at the ECPS Conference 2025, Natalie Schwabl, a doctoral candidate at the Sorbonne University, explored the entangled relationship between Catholicism, nationalism, and the construction of the Croatian national identity—specifically through the discursive deployment of the term Hrvatski narod ("the Croatian people"). Her talk, “Catholicism and Nationalism in Croatia: The Use and Misuse of ‘Hrvatski Narod’,” offered a compelling diachronic examination of how religious symbolism and political narratives have fused across different regimes to forge, sacralize, and instrumentalize national identity.

Schwabl opened her presentation by quoting historian Matveyevich, who warned of the ideological reshaping of national consciousness through mythmaking. This interpretive lens framed the entirety of her presentation, which tracked how Croatian nationalism, especially in the 20th century, was often undergirded by religious imaginaries and selectively mythologized histories. She laid out a chronological structure that traced the evolving concept of Hrvatski narod, highlighting its oscillations between heroization, victimization, and erasure, depending on the prevailing political regime.

Central to Schwabl’s analysis was the Catholic Church’s enduring role in shaping Croatian identity, especially during periods when Croatia lacked formal statehood. In both Yugoslav periods, the Church served as a surrogate national institution, reinforcing a millenarian narrative that aligned Croatia with Catholic Western Europe while casting its Orthodox and Muslim neighbors as alien others. She underscored the Church’s dual role: as both a spiritual guardian and a political actor, contributing to the persistence of a civilizational us versus them discourse.

In her discussion of the interwar period and the rise of the Ustaša movement in the 1930s, Schwabl provided a detailed account of how the movement drew heavily on 19th-century Catholic-nationalist ideas. Thinkers such as Ante Starčević and later ideologues developed a narrative of divine providence, framing Croats as a chosen people with a sacred duty to protect Western Christendom from Eastern encroachment. This narrative found powerful visual and rhetorical expression in the fascist puppet state known as the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), established in 1941 under Ante Pavelić with Nazi and Italian backing.

Schwabl examined the NDH’s ideological apparatus, showing how Catholic symbols, medievalist imagery, and notions of providential destiny were mobilized to construct a sacralized Croatian national myth. Examples included newspapers like Hrvatski narod, iconography invoking the Virgin Mary as the nation’s protector, and reinterpretations of medieval history to justify contemporary political goals. She identified these deployments as examples of “medievalism”—a selective invocation of historical tropes to legitimize nationalist claims.

The presentation then turned to the Titoist period (1945–1980), where the Yugoslav state promoted a new supranational identity centered on brotherhood and unity. Under this second Yugoslavia, Schwabl noted, the concept of narod was depoliticized and homogenized into the abstract figure of the “Yugoslav people.” The violence and complicity of Croatian actors during World War II were largely subsumed under a collective narrative of anti-fascist resistance, sidelining culpability while emphasizing shared suffering under Nazi and Axis occupation. Drawing on Luca Manucci’s theoretical framework, Schwabl mapped how this period was characterized by a triad of memory strategies: victimization, heroization, and cancellation of culpability.

Crucially, Schwabl argued that this historical amnesia laid the groundwork for the resurgence of nationalist sentiment during the Croatian Spring of the 1970s and especially in the post-1991 independence period. The Croatian Catholic Church regained institutional and symbolic prominence, often supporting revisionist interpretations of history that glorified the Ustaša regime or downplayed its atrocities. Under President Franjo Tuđman, state-Church relations intensified, with promises made to restore ecclesiastical rights and national memory restructured through a nationalist lens. The destruction of anti-fascist monuments and their replacement with Catholic and national symbols in Herzegovina served, in Schwabl’s view, as a clear example of memoricide—the systematic rewriting of public memory to align with a new ideological order.

In her final sections, Schwabl turned to contemporary Croatia. She illustrated the persistence of fascist-era symbols and slogans in public life, particularly in emotionally charged moments such as football matches or nationalist commemorations. Phrases like “Za dom spremni” (“For the homeland, ready”), once used by the Ustaša, continue to circulate, sometimes with the tacit or explicit approval of clergy. The blending of Church colors, Vatican symbolism, and national flags at public events exemplifies the dual appropriation of religion for nationalist purposes and the Church’s active participation in shaping political narratives.

Throughout her presentation, Schwabl remained attentive to the historical continuities and ruptures in the use of Hrvatski narod. She emphasized that this term has not remained stable over time but has been redefined and repurposed across different ideological regimes—monarchical, fascist, communist, and post-socialist. Each reconfiguration involved the intertwining of religious myth, political opportunism, and selective memory, often producing exclusionary and essentialist visions of national identity.

Her critical insight lay in revealing the instrumental use of religion not for theological reflection, but as a legitimizing force in nationalist projects. The Croatian case, she argued, offers a potent example of how the sacred can be weaponized for the political—and how institutions like the Church can both shape and be shaped by the forces of populism and ethno-nationalism.

In conclusion, Schwabl’s presentation was a methodologically rich and theoretically robust contribution to the ECPS Conference. By unpacking the symbolic, historical, and political dimensions of Hrvatski narod, she demonstrated how the politics of belonging in Croatia have been built upon—and continue to rely upon—the selective invocation of Catholicism, historical memory, and national myth. Her work not only sheds light on Croatia’s past and present, but also offers critical tools for interrogating the broader dynamics of religious nationalism and populist memory politics in post-socialist Europe.

Sarah Riccardi-Swartz: ‘Become Ungovernable:’ Covert Tactics, Racism, and Civilizational Catastrophe

In her deeply compelling and methodologically rich presentation, Dr. Sarah Riccardi-Swartz (Assistant Professor of Religion and Anthropology at Northeastern University) addressed the complex convergence of Christian nationalism, racialized populism, and civilizational rhetoric in the contemporary American far right. Drawing on ethnographic research, digital media analysis, and transnational theoretical frameworks, Dr. Riccardi-Swartz traced how far-right American Christians are constructing an ideologically potent imaginary of “becoming ungovernable”—a theological-political vision grounded in racial purity, anti-democratic sentiment, and an admiration for Russia’s illiberal authoritarianism.

The presentation began with Dr. Riccardi-Swartz recounting the symbolic and ideological affinities articulated by groups such as the League of the South, which has praised cultural and “bloodline” similarities between white Southerners and Russians. Such transnational rhetorical gestures serve to legitimize a shared civilizational project among white Christian ethno-nationalists, linking the American South to Putin’s Russia. In particular, figures like Michael Hill, Christopher Caldwell, and digital influencers have framed Russia as a bulwark against Western liberalism, multiculturalism, and globalism—values they associate with societal decay.

Central to Dr. Riccardi-Swartz’s argument is the paradoxical desire among these actors for both securitization and rebellion: the wish to reimpose a stable, morally homogenous society governed by Christian traditionalism, and simultaneously, the desire to become “ungovernable” within the framework of liberal democratic institutions they reject. In this vision, civilizational collapse becomes not a threat to be averted but a purifying crucible through which white Christian dominance might be re-established.

Her case study of Rebecca Dillingham, an Orthodox Christian content creator known as “Dissident Mama,” powerfully illustrated these dynamics. A former atheist and feminist turned traditionalist, Dillingham represents a new genre of far-right micro-celebrities who fuse religious conviction with white nationalist nostalgia. Her media content blends neo-Confederate symbolism, theological commentary, and conspiratorial narratives of white marginalization, all situated within a broader rejection of the American liberal order.

Dr. Riccardi-Swartz traced Dillingham’s affiliations to the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR) and her support of Putin’s geopolitical vision. Her digital content, broadcast across platforms and amplified through networks of far-right actors, promotes the mythos of white victimhood and Christian civilization under siege. She positions herself and her followers not just as culture warriors, but as defenders of an imagined moral order threatened by racial diversity, gender equality, and religious pluralism.

This fusion of Southern American nationalism with Orthodox Christian traditionalism, Dr. Riccardi-Swartz argued, reflects a larger movement among disaffected white Christians seeking sanctuary in Russia’s illiberalism. Russia, she demonstrated, has been rebranded in American far-right circles as a moral stronghold. This is evidenced by events like the World Congress of Families and by the alignment of Russian state ideology with anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, anti-feminism, and civilizational rhetoric centered on the Christian family.

Dr. Riccardi-Swartz located these trends within a longer history of white anxieties about demographic change, migration, and the collapse of racial hierarchies—what some frame as “white genocide.” However, in the digital age, these concerns are refracted through coded language and aesthetic strategies that allow for broader reach while evading direct censorship. She highlighted how new media technologies facilitate connections between American Christian nationalists and Russian Orthodox actors, allowing for transnational collaborations that rest on shared disdain for liberalism, modernity, and secularism.

Particularly disturbing, Dr. Riccardi-Swartz noted, is the resurgence of anti-Semitism and the valorization of violence. She referenced the paramilitary aspirations of groups like “The Base,” a neo-Nazi organization with operational links across the US, Russia, and Ukraine. Such networks, she argued, seek to create a white ethnostate that is unmoored from geography but unified ideologically through faith, race, and militant opposition to modern democratic institutions.

Quoting Michael Hill and other white nationalist voices, Dr. Riccardi-Swartz demonstrated how such figures view Putin’s Russia as both inspiration and ally. The invocation of spiritual warfare, “defense of the motherland,” and the Christianization of the geopolitical domain are rhetorical strategies used to frame authoritarianism as not only legitimate but divinely sanctioned.

In her concluding reflections, Dr. Riccardi-Swartz drew upon political theorist Michael Feola’s assertion that ethno-nationalism’s defining feature lies in the racialized construction of “the people.” For actors like Dillingham, whiteness and Christianity become the twin axes of moral legitimacy and national destiny. Populist suspicion of elites is not only political but deeply existential—framed as a struggle for the survival of civilization itself.

Thus, Dr. Riccardi-Swartz’s presentation unveiled the theological undercurrents of contemporary white Christian nationalism as more than a reactionary cultural force. It is, she contended, an apocalyptic vision that seeks to re-found the political order on notions of racial purity, heteronormative family values, and religious homogeneity. In doing so, it constitutes a transnational illiberal project—one that sees in Russia not an enemy of the West, but the last hope for its imagined civilizational continuity.

This presentation, situated at the intersection of religion, digital anthropology, and political extremism, was one of the most provocative of the ECPS Conference 2025. It illuminated the global dimensions of far-right mobilization, the spiritualized grammar of white grievance, and the alarming ideological bridges being built between American dissidents and Russian ethno-authoritarians. Dr. Riccardi-Swartz’s work offers a crucial lens for understanding how populism, religion, and racism co-produce new imaginaries of power and belonging in the post-liberal era.

Petar S. Ćurčić: Is There Left-wing Populism Today? A Case Study of the German Left and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance

In his analytically detailed and historically informed presentation, Petar S. Ćurčić, Research Associate at the Institute of European Studies in Belgrade, tackled a pressing question at the intersection of political theory and contemporary electoral dynamics: does left-wing populism still exist in Europe today? Through a comparative case study of Die Linke (The Left Party) and the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW, Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance for Reason and Justice), Ćurčić examined the evolving contours of left-populist mobilization in Germany in the context of broader ideological fragmentation, party realignment, and the competing appeals of radical left and right formations.

Framing his inquiry within the theoretical lens of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe’s discourse on populism—particularly the dialectic between radical reformism and revolutionary politics—Ćurčić identified post-reunification Germany as a key site where the legacy of East German socialism, structural transformations in the political economy, and shifting voter coalitions continue to shape the prospects of left populism. The fusion of the post-communist PDS (Party of Democratic Socialism) with disaffected elements of the SPD (Social Democratic Party) in the early 2000s birthed Die Linke, but the new formation was beset by internal ideological divisions that compromised coherence and hindered long-term consolidation.

The presentation mapped the electoral landscape following Germany’s 2024 federal elections, which saw Die Linke gain an unexpected boost (8.8% of the vote and six direct mandates) while the BSW failed to pass the 5% threshold required for parliamentary representation. Interestingly, Die Linke’s modest resurgence was interpreted as a function of its return to a clear outsider status, recapturing disillusioned voters from the Greens and SPD, especially those dissatisfied with the Ampelkoalition (traffic light coalition). By contrast, the BSW’s populist promise—centered around Sahra Wagenknecht’s personalized leadership and contrarian stances—sputtered under internal contradictions, policy ambiguities, and a misreading of the electorate’s tolerance for anti-immigration rhetoric within a left-wing frame.

In the first analytical section, Ćurčić assessed socioeconomic policy as the bedrock of left-wing populist appeal. Both Die Linke and BSW espoused redistributive agendas: nationalizing large housing corporations, advocating public ownership, and taxing the ultra-wealthy. These were classical populist demands—aimed at mobilizing economically marginalized constituencies against “the rich” and “corporate elites.” Yet Ćurčić noted that BSW’s more cautious embrace of this rhetoric, due to concerns about capital flight and economic stagnation, signaled strategic ambivalence.

The second dimension of analysis—migration—revealed a sharper divergence between the parties. Die Linke remained staunchly pro-immigration, defending asylum rights and inclusive multiculturalism. BSW, by contrast, advocated for migration quotas and structured assimilation—a position veering into exclusionary populist discourse more typically associated with the radical right. Although framed as a defense of working-class interests, BSW’s appeal to migration referenda (legally unviable under German constitutional law) and regional party divisions—particularly in Bavaria—highlighted both the ideological risks and operational incoherence of such positioning. Ćurčić stressed that while BSW distanced itself from AfD’s overt xenophobia, it flirted with similarly populist tropes of national destabilization through immigration.

In the third section, Ćurčić addressed the anti-fascist orientation of left populism, contrasting the firewall politics (Brandmauerpolitik) of Die Linke—a refusal to cooperate with the far-right AfD—with BSW’s critique of such strategies. While Die Linke called for mass mobilization against fascism, including street protests and institutional exclusion of AfD, BSW positioned itself as a defender of “dissenting opinion” against political correctness and establishment censorship. Wagenknecht’s rhetoric reframed the anti-AfD consensus as authoritarian overreach, drawing criticism from within her own ranks for weakening democratic resistance to extremism.

The fourth point delved into political strategy and engagement with state institutions—an often-neglected dimension in populism studies. Ćurčić underscored the strategic dilemma of left-wing populists when transitioning from opposition to governance. BSW’s brief coalition experiments in Thuringia and Brandenburg, followed by a decline in electoral support, were emblematic of the broader challenge populist parties face when tasked with compromise and administration. In response to electoral setbacks, BSW alleged vote-counting irregularities—a narrative tactic borrowed from right-wing populism and suggestive of eroding trust in democratic institutions. In contrast, Die Linke used its electoral gains to press for constitutional reforms (notably the abolition of Germany’s debt brake) and anchored itself in parliamentary activism rather than populist delegitimation of the system.

The final section of the presentation explored populist responses to war, particularly in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the conflict in Gaza. Ćurčić explained how Die Linke redefined its foreign policy stance by condemning Russian aggression and advocating a multilateral peace initiative involving the EU and Global South actors. This marked a break from its earlier ambiguity and showcased an anti-militarist, solidarity-based foreign policy that resisted both NATO interventionism and Kremlin propaganda. BSW, on the other hand, adopted an anti-war discourse rooted in economic nationalism and skepticism of Atlanticist geopolitics. Wagenknecht’s critiques of NATO expansion and warnings about Germany’s economic vulnerabilities mirrored some elements of Kremlin talking points, raising concerns about the resonance of such narratives with disaffected constituencies in Eastern Germany.

In conclusion, Ćurčić contended that the German left is undergoing a deep recalibration of its populist potential. While both Die Linke and BSW articulate critiques of neoliberalism and centrist consensus, their strategic divergences on migration, anti-fascism, institutional engagement, and foreign policy illustrate fundamentally different visions of what left-wing populism can be. For Die Linke, the path lies in reinvigorating class-based solidarities and institutional legitimacy. For BSW, the wager is on a heterodox populism that blends left economics with cultural conservatism—an experiment that, thus far, appears to have reached its electoral limits. Ćurčić suggested that the future of left-wing populism in Germany may depend on its ability to both differentiate itself from the radical right and avoid internal fragmentation in the face of complex societal challenges.

Conclusion

Panel V, Governing the ‘People’: Divided Nations, provided a timely and multi-dimensional exploration of how populist narratives around national identity, religion, race, and ideology are constructed, contested, and reconfigured across diverse geopolitical contexts. Drawing from richly sourced case studies—Croatia, the United States, and Germany—the panel offered nuanced insights into the ways in which “the people” are defined, governed, and mobilized in fractured democratic landscapes.

A recurring theme across the three presentations was the instrumentalization of collective identity—be it religious, racial, or class-based—for populist ends. Natalie Schwabl’s historical excavation of Croatian Catholic nationalism demonstrated how sacralized narratives of belonging, buttressed by the Church and selectively curated memory politics, can be wielded to legitimize exclusionary nationalisms. In parallel, Sarah Riccardi-Swartz’s ethnographic investigation into white Christian nationalism in the United States spotlighted the globalizing, digitally mediated dimensions of populist theology and its alignment with illiberal, transnational authoritarianism. Petar S. Ćurčić’s comparative study of Germany’s left-wing populist spectrum added further depth by analyzing intra-left tensions over migration, anti-fascism, and institutional trust in the wake of electoral realignments.

Together, these contributions not only affirmed the conference’s interdisciplinary ethos but also challenged simplistic binaries between populist left and right, secular and religious, or nationalist and globalist. Instead, they highlighted the hybrid and often paradoxical formations populism takes in contemporary political life. Under the thoughtful stewardship of co-chairs Dr. Leila Alieva and Professor Karen Horn, the session fostered critical reflection on the global entanglements of populist discourse and the urgent need for historically informed, context-sensitive scholarship to navigate the complexities of democratic backsliding and contested belonging in the 21st century.

Note: To experience the panel’s dynamic and thought-provoking Q&A session, we encourage you to watch the full video recording above.