Please cite as:

Biancalana, Cecilia. (2024). “The Spectrum of Italian Populist Parties in the 2024 European Elections: A Shift to the Right.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0075

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON ITALY

Abstract

Italy has historically been one of the strongest proponents of a united Europe. However, recent years have seen a rise in Euroscepticism within the country, with a notable increase in the electoral support for Eurosceptic parties. Have the 2024 elections confirmed or refuted this trend? Italy features a variety of populist parties, both on the right and on the left, each with different Eurogroup affiliations and varying positions on European integration. As a result, during the 2024 campaign, the parties adopted different strategies. The results of the 2024 elections highlight two significant trends: a decrease in turnout and the strengthened influence of Fratelli d’Italia, reflecting a sustained support for right-wing populist ideologies among Italian voters.

Keywords: populism; Euroscepticism; Fratelli d’Italia; Lega; Forza Italia; Movimento 5 Stelle; European Parliament

By Cecilia Biancalana* (Department of Culture, Politics and Society, University of Turin, Italy)

Populism and Euroscepticism in Italy: Diverse actors and perspectives

Italy is an intriguing case study for examining the role, characteristics and influence of populist parties within the European context. Its relevance is due to two primary reasons related to the role of populism in the country and the attitudes of its citizens and political elites towards Europe.

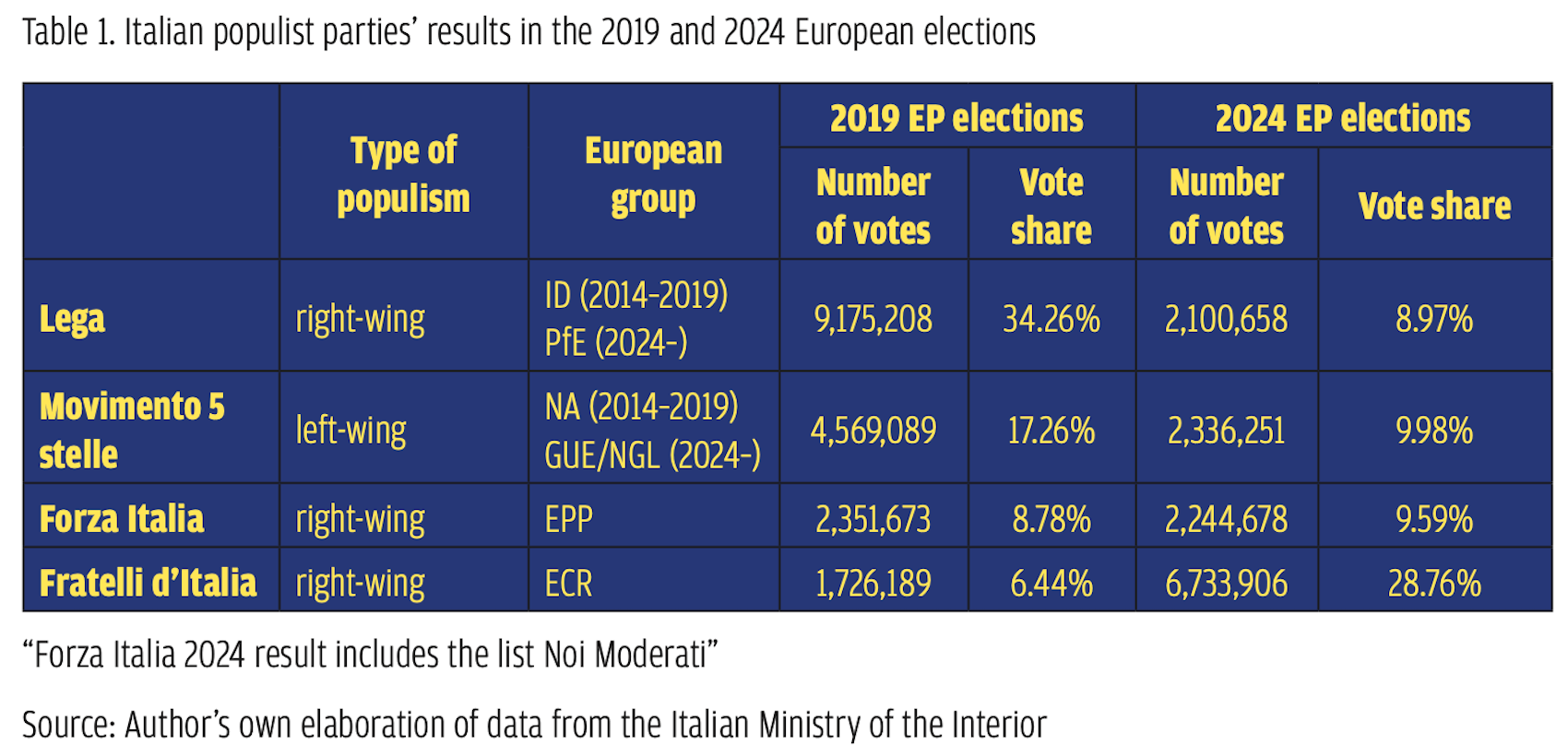

On the one hand, Italy has been described as a ‘populist paradise’ (Tarchi, 2015) due to the strong presence and variety of populist parties. Indeed, Italy hosts a spectrum of populist movements spanning both right and left ideologies (Biancalana, 2020). This diversity extends to the European stage, where, as we will see, populist parties not only exhibit varying levels of Europhilia and Euroscepticism but also belong to different European groups. Notably, within the centre-right, three Italian parties fit the model of right-wing populism to varying degrees (albeit being quite different from each other): Forza Italia (FI), Lega (officially named Lega per Salvini premier), and Fratelli d’Italia (FdI). For instance, in the 2019–2024 legislature, FI was part of the European People’s Party (EPP) group, FdI was a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), presenting a more moderate stance than the Lega, which was part of Identity and Democracy (ID). Moreover, there was also a populist party leaning towards the left, the Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S), standing among the Non-attached (NA) group of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) who do not belong to any of the recognized political groups.

On the other hand, Italy has been one of the most enthusiastic supporters of a united Europe, both at the elite level (Conti, 2017) and among the general populace (Isernia, 2008). However, it has recently become increasingly Eurosceptic (Brunazzo & Mascitelli, 2020).

Italy as a populist paradise

Regarding populism, as mentioned, Italy has long been regarded as a testing ground for populism, earning it the designation of the ‘laboratory of populism’ (Tarchi, 2015). Various forms of populism coexist within the country, which we will briefly describe, also considering their relationship with Europe. As anticipated, the leading populist parties today are FdI, Lega, FI and the Movimento 5 Stelle. Collectively, these four parties secured 58.31% (Chamber of Deputies) of the vote in the September 2022 general elections, highlighting the significant electoral strength of populism in contemporary Italy. These parties are characterized by varying degrees and types of both populism and Euroscepticism.

Scholars have categorized FdI in contrasting ways (see Bressanelli & de Candia, 2023 for a comprehensive review): post-fascist, radical-right populist and national conservative. Here, we will consider FdI as a radical right party with elements of populism and Euroscepticism (Donà, 2022). Established in 2012, the party traces its roots to the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI), a neo-fascist party founded in 1946 by supporters of former dictator Benito Mussolini. Since 2017, FdI platforms have introduced elements of nationalism, nativism and authoritarianism, along with anti-European Union (EU) stances. FdI made its electoral breakthrough in the 2022 elections, securing 25,98% of the vote and entering government for the first time under the leadership of Giorgia Meloni. The party promotes an extreme right-wing ideology, defending a homogeneous populace against perceived threats, such as LGBTQ+ groups and immigrants, particularly from Muslim-majority countries.

In the international arena, FdI advocates for national sovereignty over supranational integration while maintaining a relatively moderate stance on opposition to the EU (see Conti, di Mauro & Memoli, 2021). FdI is affiliated with the more moderate ECR group in the European Parliament (EP), of which Meloni has been president since 2020. Within the ECR group, FdI actively participates in crucial decisions alongside mainstream political factions, collaborating with them while distinguishing itself from the more radical right and Eurosceptic ID group. However, FdI continues to engage in ideological battles on specific policies such as civil liberties, environmental issues, gender equality, and EU constitutional matters (Bressanelli and di Candia 2023).

The Lega, known as Lega Nord until December 2017, was founded in 1991. Initially, it was a regionalist party (Bulli & Tronconi, 2011) that strongly advocated for Northern Italy’s interests and displayed ethnochauvinism towards Southern Italy, positioning itself against central political institutions. Since Matteo Salvini became party secretary in 2013, the Lega has shifted its focus to hostility towards immigration and European integration. Salvini’s leadership transformed the Lega’s claim and shifted the opposition to central political institutions from Rome to Brussels: the EU is portrayed as an enemy that deprives Italian citizens of resources and the freedom to determine their own destiny (Albertazzi et al., 2018; Brunazzo & Gilbert, 2017). Salvini has forged alliances with other right-wing populist parties, including France’s Rassemblement National (RN), which has been part of the same EP group: previously ID and currently the newly established group Patriots for Europe (PfE). They both held Eurosceptic views and had previously opposed the euro. However, by 2019, the Lega had dropped the idea of Italy exiting the euro, following a similar shift by Marine Le Pen in 2017.

Silvio Berlusconi’s FI was founded in December 1993 following the Tangentopoli corruption scandals. FI participated in the March 1994 general elections, securing 21,01% of the vote, heralding Berlusconi’s emergence as a prominent figure in Italian politics. Berlusconi is frequently cited as an exemplar of right-wing populism (Fella & Ruzza, 2013). As a billionaire media mogul, he entered politics as an outsider, leveraging his television channels to directly appeal to the people, a strategy that foreshadowed figures like Thailand’s Thaksin Shinawatra and Donald Trump in the United States. Historically, FI displayed ambivalent attitudes towards the EU (Conti, 2017) but has shifted towards a more pro-European stance in recent years. This transformation is partly attributed to the leadership change following Berlusconi’s passing in 2023, with Antonio Tajani, a former president of the EP, assuming leadership of the party (Biancalana, Seddone & Gallina, 2024).

The M5S is the newest among Italian populist parties and the only one not positioned on the right (Ivaldi, Lanzone & Woods, 2017; Mosca & Tronconi, 2019). Founded in October 2009 by former comedian and blogger Beppe Grillo, the party gained significant electoral momentum in the 2013 general elections, securing 25,56% of the vote (Chiaramonte & de Sio, 2014). In the 2018 general election, the M5S further increased its support, capturing 32.68% of the vote and entering a populist coalition government with Salvini’s Lega. After the collapse of the government with the Lega, the party formed a new government in partnership with the leftist Partito Democratico (PD). Between 2021 and 2022, the M5S joined Mario Draghi’s technocratic ‘grand’ coalition government.

The M5S’s relationship with Europe also reflects this fluidity and flexibility. In 2014, following its initial electoral success, the M5S campaigned against the euro, advocating for a referendum on Italy’s exit from the eurozone and rejecting significant EU financial constraints like those imposed by the ‘fiscal compact’. During the electoral campaign for the 2018 general elections, under a new leader, Luigi Di Maio, the M5S moderated its Eurosceptic stance, emphasizing that Italy’s departure from the euro was neither imminent nor planned. Nevertheless, according to Conti, Di Mauro and Memoli’s survey among MPs in 2019, when the M5S was part of a coalition government with the Lega, it could be unequivocally categorized as Eurosceptic. Furthermore, in 2019, the M5S adopted more moderate and ambivalent positions (see Conti, Marangoni & Verzichelli, 2020).

Following the dissolution of the coalition with the Lega and its subsequent alliance with the PD, the M5S supported Ursula von der Leyen’s appointment as president of the European Commission and endorsed the installation of a pro-European leader like Mario Draghi as Italy’s prime minister in early 2021, signalling a shift towards pro-Europeanism. Indeed, after five years (2014–2019) in the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy group (created by Nigel Farage) and five years in the NA group, after the 2024 elections, it joined the GUE/NGL group, signalling a clear shift towards the left at the European level as well.

Against this backdrop, what were the main issues of the 2024 campaign? How did these parties perform in the 2024 elections? Before addressing these questions, let us analyse Italians’ relationship with Europe.

The Italian case: From Europhilia to Euroscepticism

Regarding the relationship between elites and citizens and Europe, we know that historically, Italy has been a staunch supporter of European integration, with EP elections reflecting a dominant narrative that views Europe as synonymous with peace, prosperity, and political stability (Brunazzo & Mascitelli, 2020). As one of the founding members of the EU, its membership has enjoyed wide support among the political elite and the general public alike. By the early 1990s, nearly all parties shared not only broad support for the integration process but also specific support for the EU. However, the ‘permissive consensus’ supporting EU integration has been replaced by a ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe & Marks, 2009). Indeed, since the mid-1990s, the previous narrative has significantly shifted (Conti, Marangoni & Verzichelli, 2020), and both Italian citizens and political elites have become much more critical toward EU integration (Brunazzo & Mascitelli, 2020).

It has been argued that this shift is due to multiple crises, such as the financial and economic crises (including the transition to the single currency and, more recently, the Great Recession and subsequent austerity policies) and migration crises (specifically the so-called refugee crisis in 2015–2016), which have significantly affected Italy and led to increased opposition to the EU. Consequently, a considerable electoral market for Eurosceptic parties has emerged, marking a notable departure from Italy’s post-war Europhile stance and reflecting a more complex and divided perspective on European integration (Conti, di Mauro & Memoli, 2021).

This shift is exemplified by two events: the success of populist Eurosceptic parties in the general elections of March 2018 and the subsequent formation of a government by two Eurosceptic parties, the M5S and the Lega, marking a turning point in Italian history within the EU (Conti, Marangoni, & Verzichelli, 2020). The second event is the result of the 2019 EP elections, which highlighted the growing Euroscepticism within the country. The Eurosceptic Lega Nord, led by Matteo Salvini, won 34.26% of the vote. The M5S, also critical of the EU, especially the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), garnered 17.06%; for their part, FI won 8.78%, and the far-right nationalist party, FdI, received 6.44%. Have the 2024 elections confirmed or refuted this trend?

Populist parties’ campaign and issues

After five years of significant political and economic turbulence, including a general election (2022), three changes in government (the PD–M5S coalition in 2019–2021, the technocratic Draghi government in 2021–2022, and the Meloni administration starting from 2022), and multiple crises in which the EU played a notable role, such as the COVID-19 and energy crises, the 2024 European elections emerge as a crucial indicator of both internal power dynamics within Italy’s party system and within the right-wing governing coalition, as well as their positions on Europe.

Consistent with its nationalist traits, FdI’s program – entitled Con Giorgia l’Italia cambia l’Europa (‘With Giorgia, Italy changes Europe’) – emphasizes defending the identity of European peoples and nations, referencing Europe’s ‘Judeo-Christian roots’. In her final rally, consistent with her sovereigntist traits, the party leader and Prime Minister Meloni stressed that ‘Europe must rediscover its historical role, focus on a few major issues, and leave other matters to national governments that do not need centralization’ (Pinto 2024). Throughout the campaign, Meloni had to balance her dual role as prime minister, which requires international credibility and as a populist party leader, striving to maintain equilibrium between these positions.

Lega’s campaign is markedly more Eurosceptic, echoing the slogan ‘Più Italia, meno Europa’ (‘More Italy, less Europe’), which, interestingly, was previously used by FI in the 2014 European elections. Lega’s platform, Programma elezioni europee 2024, focused on halting the EU’s technocratic and centralizing drift and restoring the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality. Key proposals include rejecting the European Green Deal, ending austerity policies and protecting Italian production chains. The campaign was further stirred by the controversial candidacy of General Vannacci, a very controversial figure who ran as an independent on Lega’s lists. General Vannacci became known for his book Il Mondo al Contrario (‘The world turned upside down’), published in 2023, which sparked significant backlash due to homophobic, racist and sexist content. Despite internal opposition, Vannacci received substantial support, securing over 530,000 preferences and leading in four out of five constituencies.

Forza Italia remains the most pro-European party, presenting a ten-point program – Con noi al centro dell’Europa (‘With us at the heart of Europe’) – that includes goals like ‘building common defence and security’ and ‘reforming European treaties’. On 21 May, at a campaign event, FI’s national secretary Antonio Tajani criticized Lega’s Euroscepticism, remarking, ‘When I hear “Less Europe”, all beautiful things, but with no effectiveness and no logical sense’ (Canepa, 2024), adding that without being part of a broader project, Italy risks being overwhelmed and rendered irrelevant. Interestingly, as mentioned, this slogan was used by FI ten years ago, indicating the party’s softened positions vis-à-vis Europe over time.

In summary, on the right, Lega has sought to radicalize its stance to attract votes from those discontented with Meloni’s institutionalization, whereas FI has positioned itself as the moderate pole.

On the contrary, the Movimento 5 Stelle aimed to attract votes from the left, focusing on peace and opposing arms to Ukraine. Its program, entitled L’Italia che conta. Protagonisti in Europa (‘An Italy that counts: Protagonists in Europe’), emphasized anti-austerity measures, defence of the public healthcare system, anti-corruption efforts, environmental protection, and labour issues, including introducing a minimum wage and a 32-hour workweek.

Results: Decreased Turnout and a Shift in the Balance of Power Among Populist Parties

The 2024 European elections in Italy revealed some significant trends. The first one is the decline in voter turnout, which dropped by over 6 percentage points compared to the 2019 European elections (48.3%, down from 54.50%). This decline continues a long-term trend: turnout was 85.65% in 1979, 81.07% in 1989, 69.76% in 1999, and 66.47% in 2009.

Moreover, it is worth noting that in previous years, Italy’s voter turnout in European elections was consistently higher than the EU average. For instance, in 1979, Italy’s turnout was 85.65% compared to the EU average of 61.99%, and this pattern continued through the 1980s and 1990s. By 2019, Italy’s turnout was 54.5%, whereas the EU average was 50.66%. This trend ended in 2024, with Italy’s turnout declining further to 48.31%, while the EU average increased to 51.07%. Nevertheless, despite this increase in abstentionism, the latest Eurobarometer survey (Standard Eurobarometer 101, April–May 2024) indicates that 50% of Italians ‘tend to trust’ the EU, compared to a European average of 49%.

Regarding the performance of populist parties, it is notable that all the parties in the centre-right governing coalition (FdI, FI, Lega) improved their results compared to the 2022 general elections, the most recent national election in Italy. This outcome is significant as the ‘honeymoon’ period of the government elected in 2022 could have been expected to wane, and populist parties in office in other countries lost votes. This result marks a consolidation of the approval of the Meloni government at the domestic level.

However, it is also worth comparing the 2024 results with those of 2019, the most recent European elections. In this respect, FdI significantly increased its vote share from 6.44% in the 2019 European elections to 28.76% in the 2024 European elections, even improving on its result from the 2022 general election (25.98%). Forza Italia also improved its vote share, rising from 8.78% in the 2019 European elections to 9.59% in the 2024 European elections. This positive outcome under Antonio Tajani, the new leader following Berlusconi’s passing, indicates stable support within the electorate. In contrast, the Lega’s vote share saw a notable change, declining dramatically from 34.26% in the 2019 European elections to 9% in 2024. It is worth noting that in the 2022 general elections, the party scored 8.97%.

Within the right-wing area, we observe a shift in the balance of power between Lega and FdI: Giorgia Meloni’s party has become the strongest, while the Lega has declined. Concerning the 2022 general elections, data from the polling agency SWG (SWG 2024) shows indeed that there has been a shift of votes from other partners within the centre-right coalition towards FdI. While 68% of the votes FdI represent a confirmation of their 2022 vote, 16% come from the centre-right (8% from Lega and 8% from FI), and 16% come from other political areas (7% from other lists and 9% from abstention).

Conversely, the Movimento 5 Stelle experienced its worst performance in a national election in history. Its vote share dropped from 17.26% in the 2019 European elections to 9.98% in 2024. This result continues the decline observed in the 2022 general elections (15.43%). In the analysis of the Five Star Movement electorate conducted by SWG, it is evident that only 40% of those who chose them in 2022 reaffirmed their choice in 2024. The remaining votes were distributed as follows: 13% voted for a centre-left party, 6% for a centre-right party, 6% for another party, and a significant 35% abstained from voting.

This result can be explained by the absence of prominent candidates on the lists, indicating that the Five Star Movement failed to consolidate its political constituency. Additionally, the renewed bipolar competition in Italy between the right and left has significantly diminished the influence of a third party like the M5S. It is to be noted that the M5S shifted to the left over the years. However, left-wing voters likely feel better represented by other leftist parties, such as the PD and the Alleanza Verdi e Sinistra (AVS).

Finally, it is worth asking what the main differences between the populist parties are concerning the characteristics of their electorate. In this respect, a pre-electoral survey conducted by CISE (De Sio, Mannoni & Cataldi 2024) indicates that M5S voters differ from right-wing ones in terms of education. Right-wing parties are more popular among less-educated voters and have less support among university graduates. In contrast, the M5S draws strength from those with a secondary education. The party also receives considerable support from the unemployed, affirming its focus on social issues.

There are also some differences within the centre-right coalition (especially between FdI and Lega, the two parties whose power dynamics have reversed over the last few years), mainly regarding gender and social class. Concerning gender, FdI has a predominantly male profile, while Lega has a more female-oriented electorate. Regarding social class, the Lega is strong among the most disadvantaged classes (a relatively new trend for the Lega), while only 10% of FdI support comes from the lowest class, rising to 36% among the highest class. These figures indicate a strong complementarity between the two parties.

Conclusions

In sum, regarding the impact of populism in these elections, we note that in the 2019 European elections, the combined vote share for the right-wing populist parties – Lega, FdI and FI – was 49.5%. By 2024, this total increased to 51.7%. Including the percentages for the M5S, we see that the total for populist parties was 66.6% in 2019 and slightly decreased to 62.5% in 2024. This figure underscores the growing strength of right-wing populism in Italy and highlights a persistent and possibly deepening support for right-wing populist ideologies among Italian voters.

However, looking at the absolute votes, we note an increase in the percentage of votes for populist parties, but not in absolute terms. The votes for right-wing populist parties decreased from about 13 million in 2019 to 11 million in 2024. Including the Movimento 5 Stelle, the votes for populist parties (both right and left) fell from nearly 18 million in 2019 to just over 13 million in 2024. Abstention has also affected these parties, which may no longer be seen as a credible protest alternative to non-voting.

In summary, the results of the 2024 elections highlight two significant trends: a decrease in turnout and the strengthened influence of right-wing populism, particularly of FdI, within the centre-right coalition. Right-wing populism is increasingly prominent in Italy (at least among those who decide to vote), reflecting a sustained and potentially deepening support for right-wing populist ideologies among Italian voters.

Conversely, the steep decline of the M5S marks a critical point for the party, indicating a need for strategic reassessment and potential repositioning within the Italian political landscape. This decline could also indicate a return to bipolarity after the ‘electoral earthquake’ of 2013 (Chiaramonte & de Sio, 2014). In this new bipolar system, for the time being, FdI holds the lion’s share of the right-wing representation.

(*) Cecilia Biancalana is an assistant professor in the Department of Culture, Politics and Society at the University of Turin. Her research focuses on political ecology, party change, populism and the relationship between the internet and politics.

References

Albertazzi, D., Giovannini, A., & Seddone, A. (2018). ‘No regionalism please, we are Leghisti!’ The transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the leadership of Matteo Salvini. Regional & Federal Studies, 28(5), 645–671.

Biancalana, C. (2019). Four Italian Populisms. In Multiple Populisms (pp. 216–241). Routledge.

Biancalana, C., Seddone, A., & Gallina, M. (2024). Italy: Political Developments and Data in 2023. European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook.

Bressanelli, E., & De Candia, M. (2023). Fratelli d’Italia in the European Parliament: between radicalism and conservatism. Contemporary Italian Politics, 1–20.

Brunazzo, M., & Gilbert, M. (2017). Insurgents against Brussels: Euroscepticism and the right-wing populist turn of the Lega Nord since 2013. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 22(5), 624–641.

Brunazzo, M., & Mascitelli, B. (2020). At the origin of Italian Euroscepticism. Australian and New Zealand Journal of European Studies, 12(2).

Bulli, G., & Tronconi, F. (2011). The Lega Nord. In A. Elias and F. Tronconi (Eds.), From protest to power: Autonomist parties and the challenges of representation (pp. 51–74). Braumüller.

Canepa, C. (2024, 21 May). Tajani dimentica che lo slogan “Meno Europa” era di Forza Italia. Pagella Politica. https://pagellapolitica.it/articoli/tajani-slogan-meno-europa-forza-italia-elezioni-europee

Chiaramonte, A. & De Sio, L. (2014). Terremoto elettorale. Le elezioni politiche del 2014. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Conti, N. (2017). The Italian political elites and Europe: Big move, small change? International Political Science Review, 38(5), 534–548.

Conti, N., Di Mauro, D., & Memoli, V. (2022). Euroscepticism and populism in Italy among party elites and the public. Italian Journal of Electoral Studies (IJES), 85(1), 25–43.

Conti, N., Marangoni, F., & Verzichelli, L. (2020). Euroscepticism in Italy from the Onset of the Crisis: Tired of Europe? South European Society and Politics, 1–26.

De Sio, L., Mannoni, E. & Cataldi, M. (2024, 10 June). Chi ha votato chi? Gruppi sociali e voto. CISE. https://cise.luiss.it/cise/2024/06/10/chi-ha-votato-chi-gruppi-sociali-e-voto/

Donà, A. (2022). The rise of the Radical Right in Italy: the case of Fratelli d’Italia. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 27(5), 775–794.

Fella, S., & Ruzza, C. (2013). Populism and the fall of the centre-right in Italy: The end of the Berlusconi model or a new beginning? Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 21(1), 38–52.

Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British journal of political science, 39(1), 1–23.

Isernia, P. (2008). Present at creation: Italian mass support for European integration in the formative years. European Journal of Political Research, 47(3), 383–410.

Ivaldi, G., Lanzone, M. E., & Woods, D. (2017). Varieties of populism across a left‐right spectrum: The case of the Front National, the Northern League, Podemos and Five Star Movement. Swiss political science review, 23(4), 354–376.

Mosca, L., & Tronconi, F. (2021). Beyond left and right: the eclectic populism of the Five Star Movement. In Varieties of Populism in Europe in Times of Crises (pp. 118–143). Routledge.

Pinto, F. (2024, 1 June). Elezioni, Meloni: “Europa non sia più gigante burocratico e nano politico”. Euronews. https://it.euronews.com/my-europe/2024/06/01/elezioni-meloni-europa-non-sia-piu-gigante-burocratico-e-nano-politico

SWG (2024, 10 June). Swg Radar speciale elezioni 2024. Elezioni europee – analisi dei flussi di voto. https://www.swg.it/pa/attachment/6666e60a2e297/Radar_speciale%

20Elezioni%202024,%20Flussi%20di%20voto,%2010%20giugno%202024.pdf

Tarchi, M. (2015). Italia populista. Bologna: Il Mulino.