Please cite as:

Ulinskaitė, Jogilė. (2024). “Lithuanian Populist Far-right (In)security Discourse During the European Parliament Elections in the face of Russia’s War Against Ukraine.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024.https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0077

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON LITHUANIA

Abstract

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia has disrupted the previously perceived stability in Central and Eastern Europe (CCE) and exacerbated the prevailing sense of insecurity. The evolving circumstances are reshaping the political terrain and presenting avenues to mobilize support for the populist far right. However, to date, the far-right populist parties in Lithuania have not been successful in either national or European Parliament (EP) elections, as they have failed to surpass the required thresholds. However, the most recent European Parliament elections were an exception, with the election of a long-standing far-right politician in Lithuania as an MEP. This study delves into an analysis of the discourse employed by Lithuanian far-right populists throughout the 2024 EP election campaign, with a specific focus on the narratives pertaining to (in)security that they propagated. The investigation seeks to ascertain whether the far right capitalized on the situation to fuel discussions on crisis with the aim of attracting support and identifying the strategies utilized in constructing the narratives surrounding (in)security.

Keywords: populist far right, European Parliament election, insecurity, immigrants, European Green Deal, traditional values

By Jogilė Ulinskaitė (Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania)

Introduction

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022 disrupted the sense of stability in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), exacerbating existing widespread insecurity and evoking memories of Soviet repression. Although the unyielding support of the Lithuanian political elite and society for Ukraine has cultivated a rally around the flag effect, the prolonged conflict has underscored the critical importance of defence solutions. These conditions create a conducive environment for the far right to mobilize support. Although far-right populists thus far have been unable to surpass the 5% threshold required to secure seats in the national legislature, shifting circumstances provide the far right with opportunities to advocate for increased security measures and criticize the political establishment for its perceived inaction. The election of far-right politician Petras Gražulis to the European Parliament (EP) in 2024 signifies a change in the reception of contentious political discourse. The central question of this chapter concerns whether the far right is leveraging these conditions to acquire backing and the methodologies utilized to mould narratives of (in)security.

In this chapter, I define the populist far right as political agents who adhere to the procedural norms of democracy and are situated at the extreme right end of the left–right ideological spectrum. Their rhetoric is distinguished by populism and nativism, where the nation is viewed as a homogeneous entity that needs to be defended from both a corrupt political elite and perceived external threats (Wodak, 2019). The populist far right portrays the political elite as corrupt, acting against the populace’s interests and advancing the agenda of the European Union (Golder, 2016; Buštíková & Kitschelt, 2009; Wodak, 2019). Finally, they place a strong emphasis on traditional family values and a nostalgic yearning for an idealized past (Wodak, 2019).

This article analyses the discourse of three populist far-right political organizations. The National Alliance (Nacionalinis susivienijimas, NS) failed to secure any parliamentary seats in the 2020 elections but gained 3 out of 51 seats on the Vilnius City Council in 2023. The People and Justice Union (Tautos ir teisingumo sąjunga, TTS) held one parliamentary seat in a single-mandate constituency until late 2023. The third party, the Christian Union (Krikščionių sąjunga, KS), aligned with the Lithuanian Family Movement (Lietuvos šeimų sąjūdis, LŠS) in the 2024 EP election. LŠS, known for organizing the ‘Great March in Defence of the Family’ and other anti-government protests, won five seats across various municipal councils in spring 2023 on the ballots of different political parties. The analysis draws on electoral manifestos, official election debates and communications via official Facebook pages and websites during the EP election campaign.

In this chapter, I present the results of the EP elections in Lithuania and then examine the rhetoric employed by Lithuanian far-right populists during the election campaign, focusing particularly on articulated narratives of (in)security. The analysis looks at whether the campaign focused more on leveraging the crisis – a tactic often used by the Lithuanian far right – or if it instead tried to offer ideas for creating security in a volatile situation.

European Parliament election campaign and results

The 2024 EP elections in June marked the third time Lithuanian voters had been to the polls within six weeks, leading to an intertwining of election debates across different institutions. The preceding presidential election had dominated both public and political agendas, with some candidates leveraging it to boost their popularity ahead of the EP elections. Additionally, national parliamentary elections scheduled for autumn compelled many candidates to focus their campaigns on domestic issues. As a result, EP election debates were heavily dominated by national concerns, such as social benefits and employment, rather than EU-specific policies. The compressed electoral timeline and emphasis on national issues may have contributed to voter fatigue, as evidenced by the low turnout for the EP elections (28.94%), which was significantly lower than in previous years when it coincided with the presidential runoff (53.48% in 2019 and 47.35% in 2014).

The 2024 EP elections in Lithuania saw voters lean towards mainstream candidates and a significant degree of continuity, with five of the country’s eleven elected MEPs retaining their seats from the previous term. Moreover, two of the new MEPs had previously served as European Commissioners, further reinforcing the presence of experienced EU-level politicians on the Lithuanian slate. The most successful parties were the Homeland Union–Lithuanian Christian Democrats, who won three seats and 20.92% of the vote. The Social Democratic Party of Lithuania came second with two seats and 17.63% of the vote. The following political parties shared the remaining six seats, taking one each: Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union (8.95%), Freedom Party (7.94%), the Union of Democrats ‘For Lithuania’ (5.84%), Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania–Christian Families Alliance (5.67%), the People and Justice Union, TTS (5.34%), Liberals’ Movement (5.31%).

The notable exception to the support for the mainstream was electing Petras Gražulis, a leader of TTS, with 5.45 % of votes. TTS is itself an amalgam of several outfits, including the Centrists–Nationalists, Gražulis’ political movement ‘For Lithuania, Men!’ (Už Lietuvą, vyrai!), and the Union of Lithuanian Nationalists and Republicans. Lacking a cohesive ideological core, TTS has been predominantly associated with the persona of its leader, Gražulis, since 2021. Gražulis, a figure of notable controversy, has garnered international attention, including recognition on Politico’s list of the most eccentric MEPs (Wax & Cokelaere, 2024). His political profile is characterized by determined opposition to the LGBTQ+ community, particularly evident in his contentious engagement with ‘Pride’ events. The controversy surrounding Gražulis extends beyond rhetoric into legal domains. He is currently facing criminal prosecution for alleged defamation of LGBTQ+ individuals (Steniulienė et al., 2024), which led to him being denied joining and questioning by the EP party of his choice – the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group. Eventually, he joined the Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) group.

Gražulis, who served as a member of the Seimas (Lithuania’s parliament) from 1996 to 2023, has consistently secured his position through single-mandate constituency victories. His political career reached a critical juncture in the winter of 2023 when he was impeached by the Seimas. The impeachment process, triggered by his unauthorized voting on behalf of another MP, culminated in a ruling by the Constitutional Court that the politician had broken his oath of office and violated the constitution (Gaučaitė-Znutienė et al., 2023). During election debates, Gražulis strategically reframed this decision as political persecution to express his indignation and to present himself as a victim of censorship and political repression. The election outcomes indicate that his party achieved significant success in the regions outside the major cities of Lithuania. A decline in voter turnout, the dissolution of the right-wing populist party Order and Justice (Andrukaitytė, 2020), and the absence of other ideologically similar political leaders (such as Remigijus Žemaitaitis, another controversial right-wing politician) in the EP elections all contributed to the backing received by this politician.

In general, the populist far-right parties in Lithuania experienced limited electoral success. Only one such party surpassed the 5% threshold necessary for representation. Despite conducting an intensive campaign, the National Alliance expressed disappointment with its performance, garnering only 3.79% of the vote. In a post-election press conference, one of the party’s leaders, Vytautas Sinica, posited that their programmatic provisions and discourse might have been too complex for the electorate, suggesting a potential reconsidering of their campaign strategy ahead of the national elections. The Christian Union’s even less favourable outcome, securing only 1.37% of the votes, further underscores the challenges far-right parties face in Lithuania.

Prioritizing culture wars over the war in Ukraine: Fighting the usual suspects

Despite the prevalent focus in Lithuanian public discourse on the war against Ukraine (and the Russian threat) and broader defence and security matters, the far-right narrative gives precedence to Lithuania’s internal security. All scrutinized political parties emphasize the nation’s sovereignty over EU federalism and express a dedication to shielding the nation from the ‘dictates of EU bureaucrats’ and the so-called ideologies promoted by the EU, such as genderism and multiculturalism. Safeguarding the nation and traditional family values serves as the foundation and primary perspective through which all other matters are examined.

For example, the Christian Union asserts that Lithuania encounters a dual threat: ‘Our country and the entirety of European civilization face the threat of war, while internally Lithuania is undermined by an ideology that is hostile to the natural family, the Lithuanian language, culture and traditions, Christian values and scientific truths’ (Central Electoral Commission, 2024). Nevertheless, every other section of the manifesto highlights the importance of safeguarding family and traditional values. Similarly, the National Alliance’s campaign material prominently features the threat of war but as a backdrop. The primary focus of the National Alliance’s propositions is the defence of traditional European cultural values against EU bureaucrats and their supposed intentional effort to push Europe toward a multicultural identity to undermine the authority of nation-states.

These so-called ideological dangers are linked to the Istanbul Convention, an international agreement to prevent and combat violence against women, which is yet to be ratified in Lithuania and is vehemently opposed by far-right political groups. The Istanbul Convention is labelled as the ideology of genderism – a foe deemed worthy of resistance by A. Rusteika (Jursevičius, 2024) or a social engineering venture rooted in Marxist ideology, aiming to dismantle the family structure in Europe by Radžvilas (Jursevičius, 2024).

Another identified adversary is the LGBTQ+ community. The EP elections coincided with Vilnius Pride – a fact not overlooked by the National Alliance. The party noted that the demands from the LGBT community are endless, starting from recognition and parades to gender transition rights, marriage, and adoption (Sinica, 2024).

The spectre of communism is continuously brought up by the far right to evoke cultural trauma from the Soviet era. The character and magnitude of this threat were most eloquently articulated by the elected MEP: “Europe today is simply a poison that brings genderism, drugs and everything else that destroys the idea of the founding fathers, whether Schuman or Adenauer, who created this Europe. Now, they are destroying all values, Christian values, by introducing Leftism, same-sex marriage and all these perversions. I want to tell you that we are going backwards; in fact, Europe has returned to the ideas of Russia or even Lenin…. If these values return, the family will be destroyed; with what they are doing, there will be no more Europe [in the future]” (Pumprickaitė, 2024).

In addition to these internal threats emanating from the EU, migration is another usual suspect in the list of far-right threats. The image of migrant flows, so characteristic to the discourse of the EU’s far-right politicians, is also articulated in Lithuania, with a particular focus on Russian-speaking migrants. The unprecedented influx of immigrants in 2022, primarily driven by the reception of Ukrainian refugees, and the subsequent 15% increase in the foreign population in 2023 have catalysed the securitization of discourse.

The far right’s strategic focus on Russian-speaking migrants from Belarus and Central Asia suggests selective targeting of specific groups of immigrants. Migrants, both those trying to cross the border illegally and those who have obtained visas to work in Lithuania (mainly from Central Asian countries and Belarus), are portrayed as a homogenous group and as ‘invaders’, disloyal to the Lithuanian government and a threat to Lithuanian identity. Meanwhile, refugees from Ukraine are rarely mentioned by the far right. In a society that still actively supports Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees – some 89% of Lithuanians agree that Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war should be accepted (European Commission, 2024) – it is difficult to portray them as malicious intruders. Although the governing political parties have taken stringent measures to restrict migration across the Belarus–Lithuania border, the far right has also criticized the government for being insufficiently restrictive and ‘kept the borders open until the European Commissioner for Migration herself came to Lithuania and authorised the turnarounds’ (Radžvilas & Sinica, 2024).

The European Green Deal is a new usual suspect emerging in the rhetoric of the Lithuanian far right. The Green Deal and renewable energy policies are framed as ‘extremist’ and examples of ideological ‘fanatism’ emanating from Brussels aimed at burdening ordinary citizens with regulations and fines (Radžvilas, 2024a). While nominally supporting environmental protection, they advocate for a ‘rational’ approach (Central Electoral Commission, 2024: 21) that does not ‘ruin the European economy’ (Central Electoral Commission, 2024: 18).

This stance allows the far right to position themselves as pragmatic defenders of national economic interests against perceived EU overreach. First, the EU environmental policies are portrayed as a threat to Lithuanian farmers, who are purportedly already disadvantaged by lower EU subsidies than their counterparts in the West. Secondly, it is argued that environmental restrictions impose undue burdens on businesses, potentially compromising competitiveness (Tapinienė, 2024). The far right’s unexpected positioning as defenders of both business and agricultural interests during the EP election campaign represents a strategic adaptation of their rhetoric.

Security issues: bridging defence and social conservatism

Security and defence issues, already prominent in the CEE region, have come to dominate Lithuania’s public discourse, not least because of the election of the president of Lithuania in the spring, the official who is the commander-in-chief of the Lithuanian armed forces. Security and defence issues dominated the election debates and are also at the forefront of public opinion: a recent Eurobarometer survey shows that 60 % of Lithuanians (in contrast to 37 % of EU citizens) argue that the EU should focus more on defence and security issues to reinforce its position globally (European Parliament, 2024). In response to perceived security challenges, the Lithuanian government has implemented a series of proactive measures, including augmenting defence expenditure, planning strategic military acquisitions and initiating reforms to the conscription system.

Within this heightened security context, far-right political organizations find themselves compelled to engage with international security issues. Their security discourse is characterized by a multifaceted narrative that interweaves the concepts of national defence, national identity and traditional family values. This rhetorical strategy positions these parties as unique defenders of both conservative societal norms and robust national security.

Gražulis, the People and Justice Union leader, presented a forceful critique of the West. He asserted that the root cause of conflicts, including the current war, is the accommodating stance of US President Biden and the Western powers more broadly (Tapinienė, 2024). Furthermore, he censured the Lithuanian government, alleging that it is stoking tensions and provoking Putin. Gražulis’ proposed remedy for the prevailing insecurity is the election of Donald Trump as the president of the United States. He revealed that his outfit had opened an electoral campaign office in Lithuania supporting Trump, emphasizing the former US president’s purported dedication to peace and traditional values: ‘We support Trump’s views on the traditional family and traditional values. We trust Trump’s promise to end the war in Ukraine within 24 hours, at the expense of Russia’ (ALFA.LT, 2024).

Within the discourse of the National Alliance, a distinct sentiment of distrust towards international partners in the West is evident. Vytautas Radžvilas, the National Alliance leader, portrays Lithuania as positioned within the ambiguous sphere situated between the two competing geopolitical forces of Russia and the West. While advocating for the development of the defence industry at the national level and financial support at the EU level in the party manifesto, Radžvilas simultaneously contends that in the event of a conflict, no NATO or European allies would intervene to protect Lithuania (Radžvilas, 2024b). Specifically, he underscored a sense of mistrust towards the United States in light of the shift in US strategic focus toward the Pacific Ocean region (Beniušis et al., 2024). Conversely, the Western European allies are depicted as engaging in friendly interactions with Russia. Even the deployment of a German army brigade to Lithuania, although welcomed, does not instil complete confidence, and the primary focus remains on bolstering Lithuania’s national defence capabilities (Ibid.). The proposed solution is two-fold. Firstly, to enhance sovereignty and national security for self-defence, Lithuania must strive for independence from Brussels (Radžvilas, 2024b). Secondly, Lithuania should rally a coalition comprising Central Eastern European and Scandinavian nations to advocate for reforms within EU policy (Beniušis et al., 2024).

All analysed political parties endorse the European integration of Ukraine. It appears inevitable in a country where, as of May 2024, 77% of Lithuanians supported granting Ukraine candidate status (European Commission, 2024). However, even this pro-European stance is exploited by the far right to advance their political agenda. Gražulis and the Christian Union advocate for Ukraine’s accession, citing its potential to combat ‘genderism’ and uphold Christian principles. Nevertheless, there are lingering reservations. Aurelijus Rusteika, one of the leaders of the Lithuanian Family Movement, highlights concerns that the European project entails a loss of national sovereignty, prompting questions about Ukraine’s willingness to relinquish its autonomy to Brussels (Jursevičius, 2024). Additionally, the National Alliance posits that the integration decision will be a pivotal choice between the major geopolitical players, namely the West and Russia (Jursevičius, 2024). Even in cases where unequivocal public backing exists, the far right manages to cultivate an environment characterized by scepticism and lack of clarity.

Conclusion

The European Parliament election in 2024 marked a significant milestone as the populist far right in Lithuania managed to surpass the 5% electoral threshold for the first time. Factors such as support from regions outside major cities, low voter turnout, the disbandment of the right-wing populist party Order and Justice, and the absence of similar ideological leaders in the EP elections all contributed to the rise of politician Petras Gražulis. Nevertheless, it is crucial to note that current circumstances have seen political parties engaging in debates that reinforce narratives of insecurity in society.

The party led by Petras Gražulis, along with other political entities under scrutiny, navigate their rhetoric by considering prevailing societal attitudes towards Ukraine and Ukrainians while also fuelling discontent towards familiar targets such as the Istanbul Convention and the LGBTQ+ community. However, notwithstanding the difficult security situation prevailing in the region, the primary focus of policymakers has centred on the cultural wars within the state. This year, the influx of migrants originating from Belarus and Central Asia, as well as the implications of the European Green Deal on farmers and businesses in Lithuania, have been underscored as potential threats to the nation. Although the analysed political parties emphasize their commitment to the security and defence of Lithuania, their discourse primarily reflects a deep-seated scepticism towards international partners, emphasizing the pivotal role of upholding Lithuania’s sovereignty and implementing national defence strategies as the key to ensuring security both at the global level and domestically. However, the European elections in June are not the end of the story; the national parliamentary elections in autumn will be another opportunity for far-right populist parties in Lithuania to repeat established and articulate new (in)security narratives.

(*) Jogilė Ulinskaitė is Associate Professor at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University. She defended her PhD thesis on the populist conception of political representation in Lithuania in 2018. Since then, she has been researching the collective memory of the communist and post-communist past in Lithuania. As Joseph P. Kazickas Associate Research Scholar in the Baltic Studies Program at Yale University in 2022, she focused on reconstructing emotional narratives of post-communist transformation from oral history interviews. Her current research integrates memory studies, narrative analysis and the sociology of emotions to analyse the discourse of populist politicians. Email: jogile.ulinskaite@tspmi.vu.lt

References

ALFA.LT. (2024, 10 April). P. Gražulis su bendražygiais įsteigė D. Trumpo rinkiminį štabą Lietuvoje. ALFA.LT. https://www.alfa.lt/aktualijos/lietuva/p-grazulis-su-bendrazygiais-isteige-d-trumpo-rinkimini-staba-lietuvoje/326687/https://www.alfa.lt/aktualijos/lietuva/p-grazulis-su-bendrazygiais-isteige-d-trumpo-rinkimini-staba-lietuvoje/326687/

Andrukaitytė, M. (2020, 21 July). Likviduojama „Tvarka ir teisingumas’ mėgino registruotis rinkimams. 15min.lt. https://www.15min.lt/naujiena/aktualu/lietuva/likviduojama-tvarka-ir-teisingumas-megino-registruotis-rinkimams-56-1350422

Beniušis, V., Čiučiurkaitė, A., Bukšaitytė, D., Lisauskas, S., & Zaveckytė, L. (2024, 6 June). 15min Europos Parlamento debatai 2024: karšta diskusija dėl karo, lyčių lygybės ir klimato kaitos [15min European Parliament Debates 2024: a heated debate on war, gender equality and climate change] [Video]. 15min. https://www.15min.lt/video/15min-europos-parlamento-debatai-2024-karsta-diskusija-del-karo-lyciu-lygybes-ir-klimato-kaitos-254928

Buštíková, L., & Kitschelt, H. (2009). The radical right in post-communist Europe. Comparative perspectives on legacies and party competition. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 42(4), 459–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2009.10.007

Central Electoral Commission. (2024). Lietuvos Respublikos vyriausiosios rinkimų komisijos leidinys: 2024 m. birželio 9 d. rinkimai į Europos Parlamentą [Publication of the Central Electoral Commission of the Republic of Lithuania: 9 June 2024, European Parliament Elections]. Central Electoral Commission. https://www.vrk.lt/documents/10180/787387/Leidinys+A5+Europos+Parlamento+2024.pdf/50858a94-753f-4ec8-8f86-d0fac621860f

European Commission. (2024). Standard Eurobarometer 101. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3216

European Parliament. (2024). EP Spring 2024 Survey: Use your vote – Countdown to the European elections. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3272

Gaučaitė-Znutienė, M., LRT.LT, & ELTA. (2023, 18 December). Gražulio Seime nebeliks – už mandato naikinimą balsavo 86 Seimo nariai. LRT.LTlrt.lt. https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/2152920/grazulio-seime-nebeliks-uz-mandato-naikinima-balsavo-86-seimo-nariai

Golder, M. (2016). Far Right Parties in Europe. Annual Review of Political Science, 19(1), 477–497. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042814-012441

Jursevičius, D. (2024, 20 May). Rinkimai 2024. Kandidatų į Europos Parlamentą debatai [Elections 2024. Debates between candidates for the European Parliament] [Video]. LRT.LT. https://www.lrt.lt/mediateka/irasas/2000341616/rinkimai-2024-kandidatu-i-europos-parlamenta-debatai

Pumprickaitė, N. (2024, 21 May). Rinkimai 2024. Kandidatų į Europos Parlamentą debatai [Elections 2024. Debates between candidates for the European Parliament] [Video]. In LRT.LT. https://www.lrt.lt/mediateka/irasas/2000342304/rinkimai-2024-kandidatu-i-europos-parlamenta-debatai

Radžvilas, V. (2024a, 24 January). Tebūnie Žaliasis kursas, net jei žūtų Lietuva!https://susivienijimas.lt/straipsniai/vytautas-radzvilas-tebunie-zaliasis-kursas-net-jei-zutu-lietuva/

Radžvilas, V. (2024b, 14 May). Lietuva: ES valstybė ar Šiaurės Rytų pasienio kraštas? Delfi. https://www.delfi.lt/news/ringas/politics/vytautas-radzvilas-lietuva-es-valstybe-ar-siaures-rytu-pasienio-krastas-120013008

Radžvilas, V., & Sinica, V. (2024, 11 April). Europai reikia pertvarkos [Europe needs transformation]. Nacionalinis Susivienijimas. https://susivienijimas.lt/straipsniai/vytautas-radzvilas-vytautas-sinica-europai-reikia-pertvarkos/

Sinica, V. (2024, 8 June). VAIVORYKŠTĖS GALO PRIEITI NEĮMANOMA. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/nacionalinissusivienijimas/posts/768004178852938?ref=embed_post

Steniulienė, I., Smirnovaitė, V., & ELTA. (2024, 17 June). VRK: Gražulis gali būti teisiamas LGBTQ asmenų niekinimo byloje, jis dar neturi imuniteto. LRT.LT. lrt.lt. https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/2298883/vrk-grazulis-gali-buti-teisiamas-lgbtq-asmenu-niekinimo-byloje-jis-dar-neturi-imuniteto

Tapinienė, R. (2024, 4 June). Rinkimai 2024. Kandidatų į Europos Parlamentą debatai [Elections 2024. Debates between candidates for the European Parliament] [Video]. In LRT.LT. https://www.lrt.lt/mediateka/irasas/2000344224/rinkimai-2024-kandidatu-i-europos-parlamenta-debatai

Wax, E., & Cokelaere, H. (2024, 14 June). The 23 kookiest MEPs heading to the European Parliament. POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/23-kookiest-meps-european-parliament-election-results-2024/

Wodak, R. (2019). Entering the ‘post-shame era’: the rise of illiberal democracy, populism and neo-authoritarianism in EUrope. Global Discourse, 9(1), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1332/204378919X15470487645420

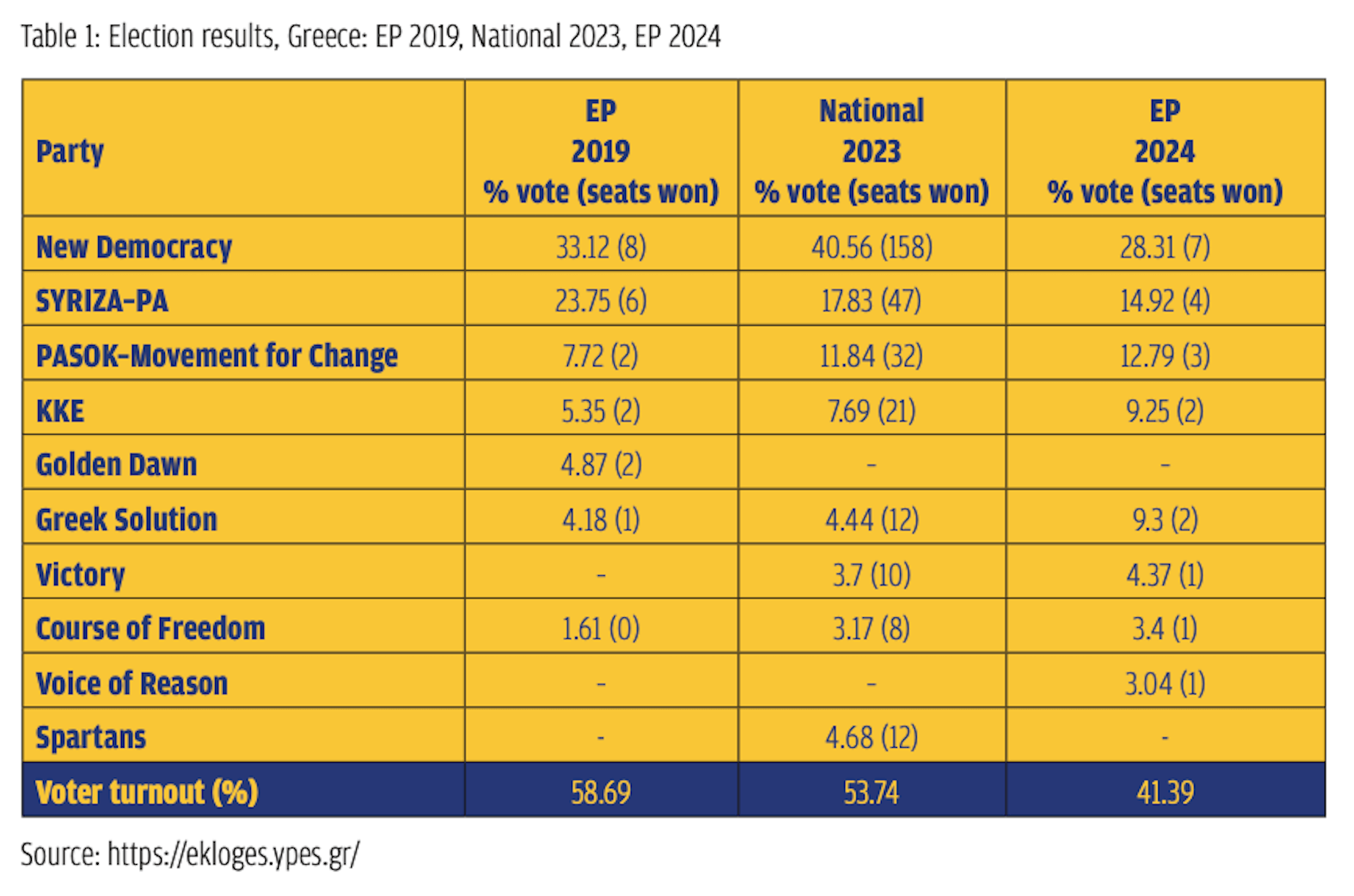

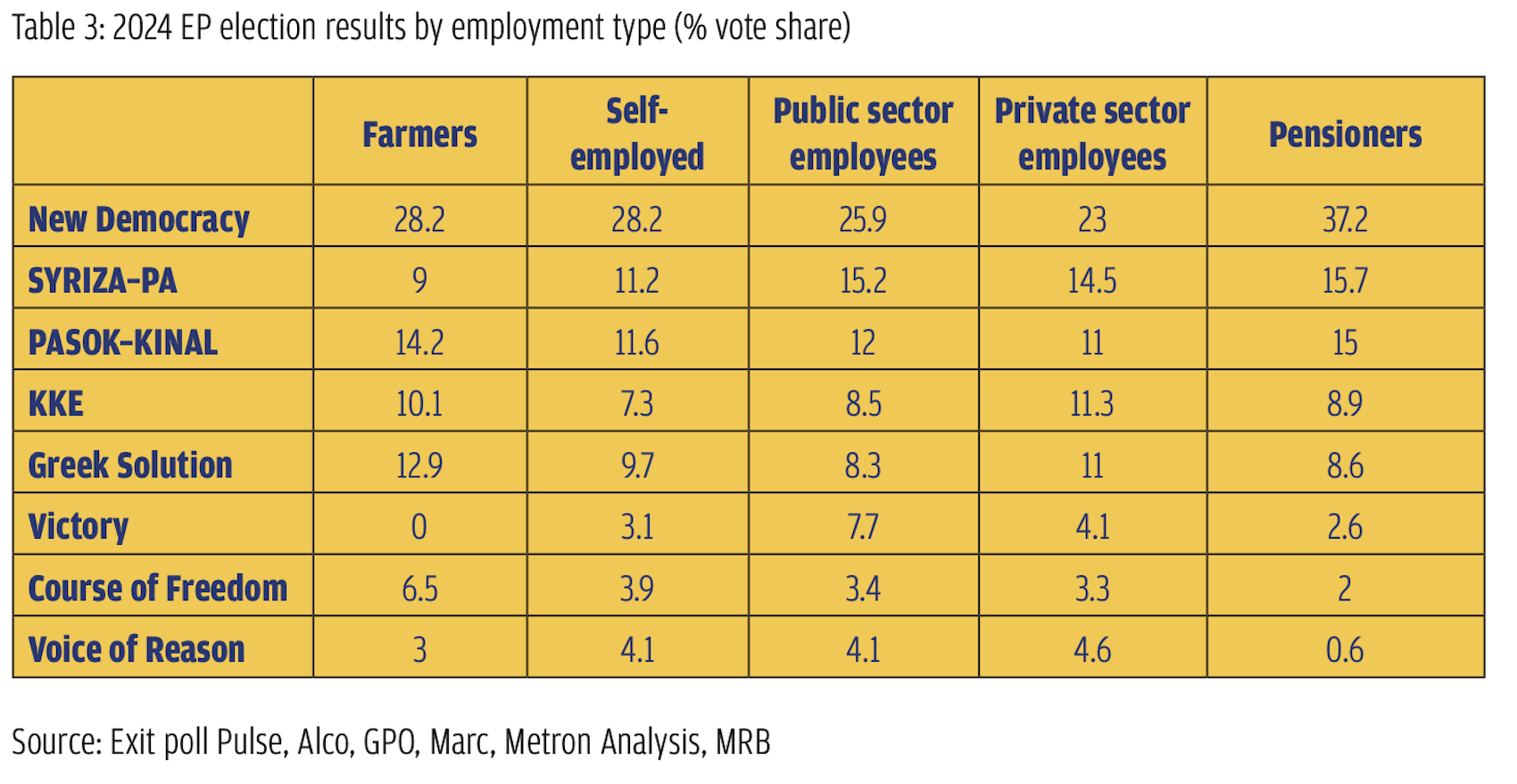

There is also an interesting geographic dimension to the far-right populist vote (for a European perspective, see also Ejrnæs et al., 2024). In many districts in Northern Greece, these parties received above-average results. Specifically, Greek Solution came second in six electoral districts of the north, including Imathia (18.42%), Pella (17.28%), Kilkis (16.54%), Thessaloniki B (15.82%), Serres (15.64%), and Drama (15.52%).

There is also an interesting geographic dimension to the far-right populist vote (for a European perspective, see also Ejrnæs et al., 2024). In many districts in Northern Greece, these parties received above-average results. Specifically, Greek Solution came second in six electoral districts of the north, including Imathia (18.42%), Pella (17.28%), Kilkis (16.54%), Thessaloniki B (15.82%), Serres (15.64%), and Drama (15.52%).

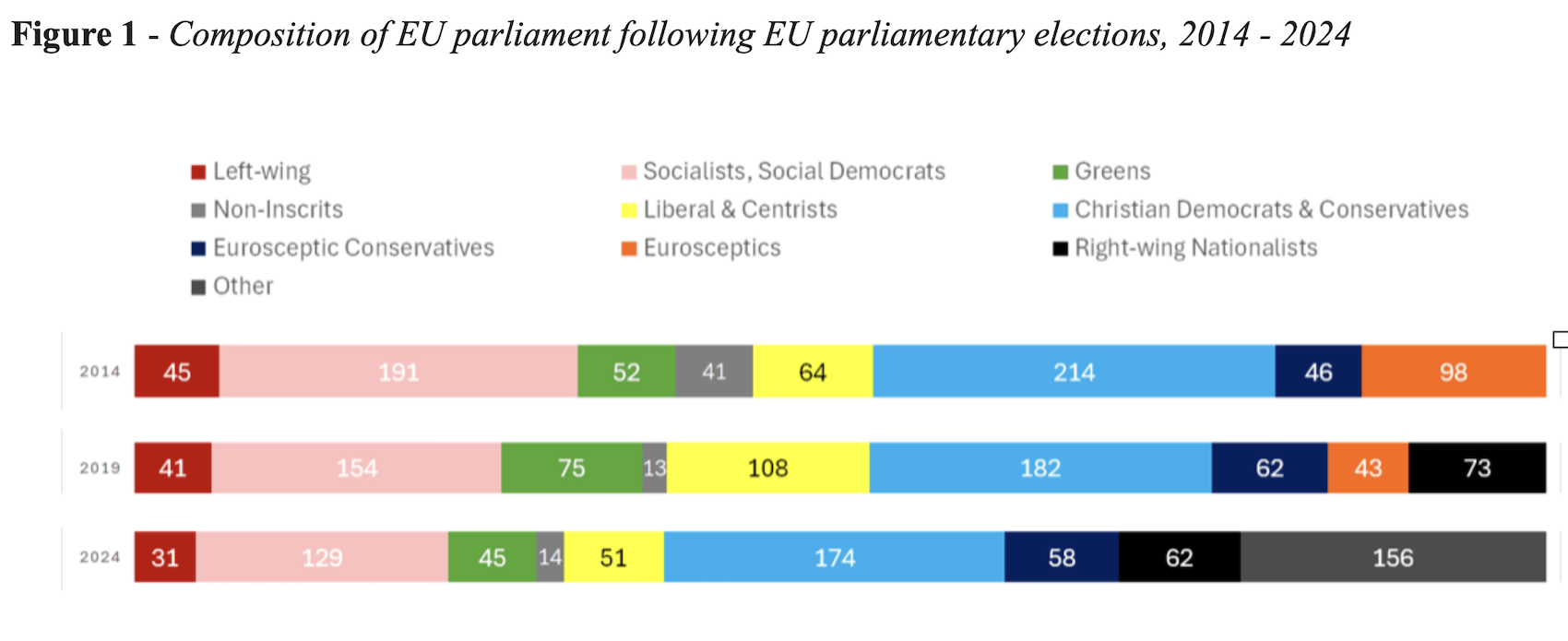

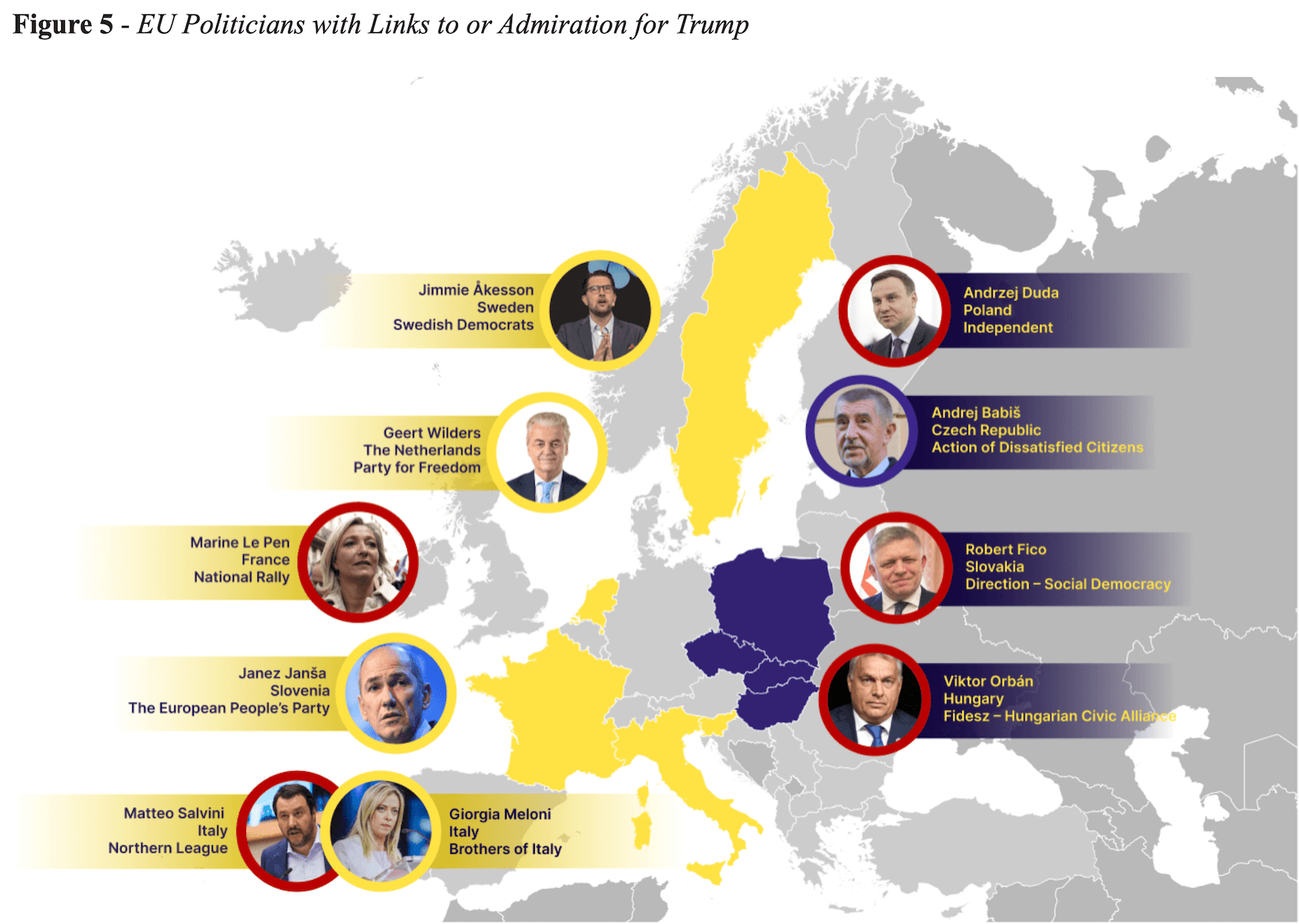

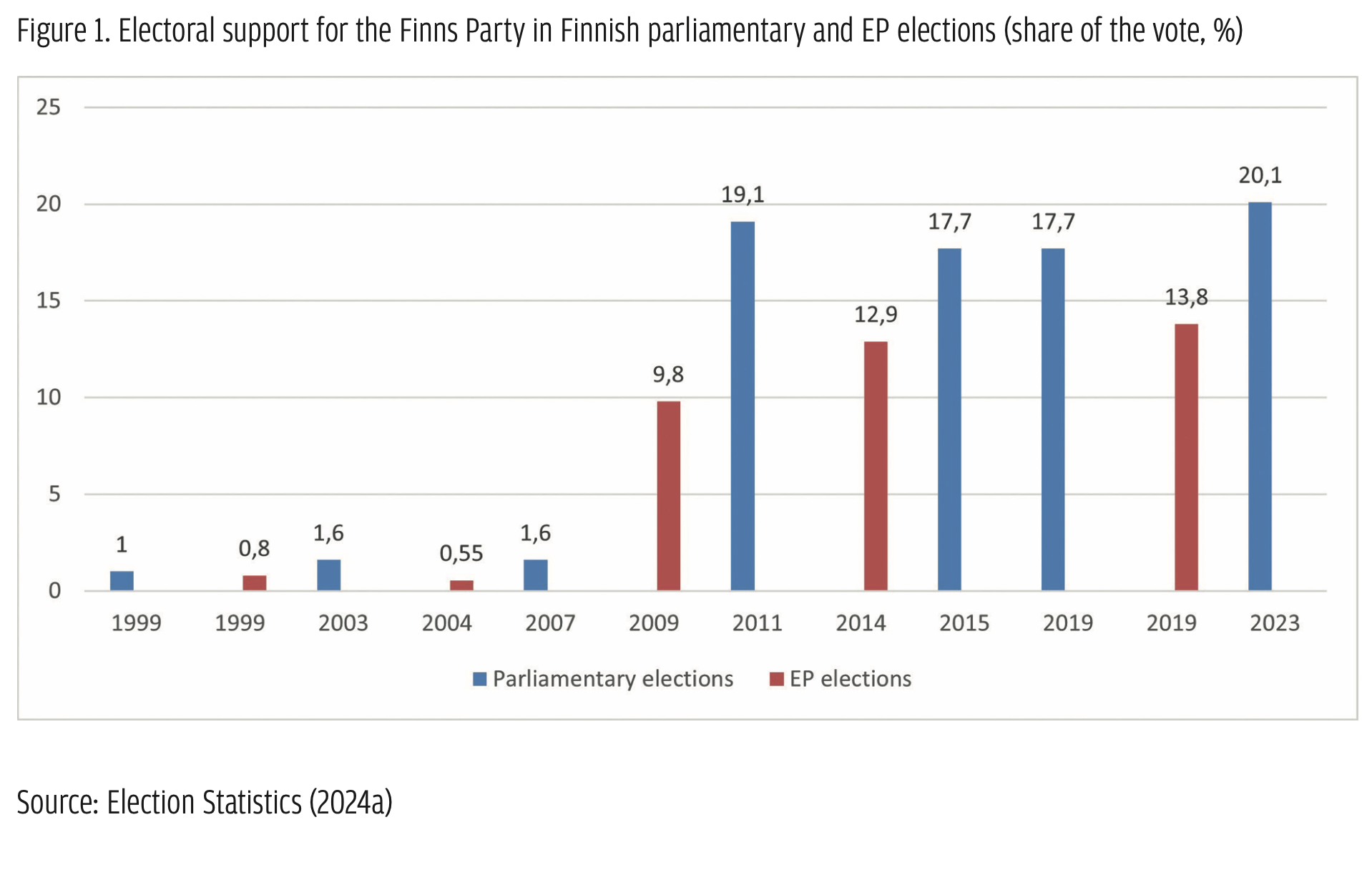

Europe has also faced difficulties controlling the increasing numbers of its migrant population. According to the International Organization for Migration (McAuliffe & Oucho, 2024), there are approximately 87 million migrants living in Europe. In the context of migration crises, which often disproportionately impact EU member states, balancing European cohesion has fragmented the Union. Additionally, in recent years, Western politics has witnessed a trend of a right-wing shift (see Figure 1) and increased support for populist leaders, which exacerbates this fragmentation (Europe Elects, 2024; Europe Politique, 2024).

Europe has also faced difficulties controlling the increasing numbers of its migrant population. According to the International Organization for Migration (McAuliffe & Oucho, 2024), there are approximately 87 million migrants living in Europe. In the context of migration crises, which often disproportionately impact EU member states, balancing European cohesion has fragmented the Union. Additionally, in recent years, Western politics has witnessed a trend of a right-wing shift (see Figure 1) and increased support for populist leaders, which exacerbates this fragmentation (Europe Elects, 2024; Europe Politique, 2024).