Please cite as:

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON ESTONIA

Abstract

Although past European Parliament (EP) elections in Estonia have witnessed the success of an anti-establishment candidate, Estonian EP elections are not generally fertile soil for populism. Estonian EP elections tend to be dominated by the liberal and progressive parties and candidates with notable foreign policy track records. The 2024 EP elections generally confirmed this pattern but also witnessed the conservative parties running on a second-order election agenda critical of the government and parties both on the right and left-wing edges of the spectrum tapping into the small but nonetheless committed pool of Eurosceptic voters. Moreover, most parties made use of the stylistic repertoires of populism, attempting to perform various crises. While the election results changed little in the overall composition of the Estonian MEP delegation, the events unravelling immediately after the election suggest that the Estonian populist radical right will become more diverse but also more isolated from its sibling parties on the European level.

Keywords: Estonia, populism, Euroscepticism, sovereigntism, second-order elections, European Parliament

By Mari-Liis Jakobson* (School of Government, Law and Society, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia)

Background

In Estonian politics, populism tends to manifest as a discursive or performative strategy or a policy logic rather than an ideological fixture (Jakobson et al., 2012). Only a handful of parties have been dubbed as populist. For example, the Estonian Conservative People’s Party (EKRE) has typically been characterized as a populist radical-right party (Petsinis, 2019; Kasekamp et al., 2019; Saarts et al., 2021). It entered the European Parliament (EP) and joined the Identity and Democracy (ID) group in 2019. Historically, the Centre Party under the charismatic leadership of Edgar Savisaar (1991–1995, 1996–2016) was characterized as left-wing populist (Jakobson et al., 2012). However, since 2016, the party has undergone two leadership changes and substantive shifts in both its political style and program. In addition, populism has been a strategy of new protest parties, but most of them have been relatively short-lived (Auers, 2018).

The limits of populist appeals have applied in EP elections, in particular, as they are characterized by a generally low electoral turnout and lower level of populist performance since, typically, the more highly educated voters with a political preference turn out to vote. The notable exception occurred in 2009, when a protest candidate, Indrek Tarand, scored over a quarter of the popular vote on an anti-partitocracy platform, criticizing the cartelization of (established) parties and neglecting the actual will of the people (Ehin & Solvak, 2012). Hence, the present report will also analyse the use of populist strategies across parties regardless of whether they are mainstream or fringe or where they are placed on the socioeconomic (left–right) or sociocultural (GAL–TAN) spectrum.

The 2024 EP elections took place 15 months after the general election in Estonia, and a liberal coalition consisting of the Reform Party, Estonia 200 and the Social Democratic Party were in power. Unlike in the previous electoral cycle, where stable coalition formation was difficult due to the distribution of parliamentary seats, the liberal parties had a comfortable majority during the 2024 EP elections. Nevertheless, there were notable tensions in the air regarding the national budget. Due to the war in Ukraine, where Estonia has been one of the most generous supporters of Ukraine in terms of GDP, Estonia has raised its defence spending to 3% of GDP and now struggles with a looming budget deficit. These budget tensions prompted the new government coalition to plan cuts and propose new taxes (e.g., a previously non-existent car tax) and raise existing ones (e.g., VAT and income tax from 20% to 22%), which has been politically difficult, especially as the Reform Party and Estonia 200 are economically right-leaning parties. Upon formation, the governing coalition christened itself as the Pain Coalition, forced to take painful decisions.

Due to this, also the EP 2024 election followed the logic of second-order elections to a great extent, where many parties tried to pitch the election as a referendum on the government’s policy, although for a large share of voters, this was outshined by issues related to the Russia–Ukraine War. Second-order elections essentially entail a significant share of anti-establishment politics, with the opposition in the national government criticizing the ruling elites and attempting to position themselves as the true representative of the virtuous people (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017). Populism’s emphasis on popular sovereignty also entails Eurosceptic attitudes, although, in Estonia, most parties resort to, at worst, soft Euroscepticism (Taggart & Szerbiak 2001), and this remained true in the 2024 EP election.

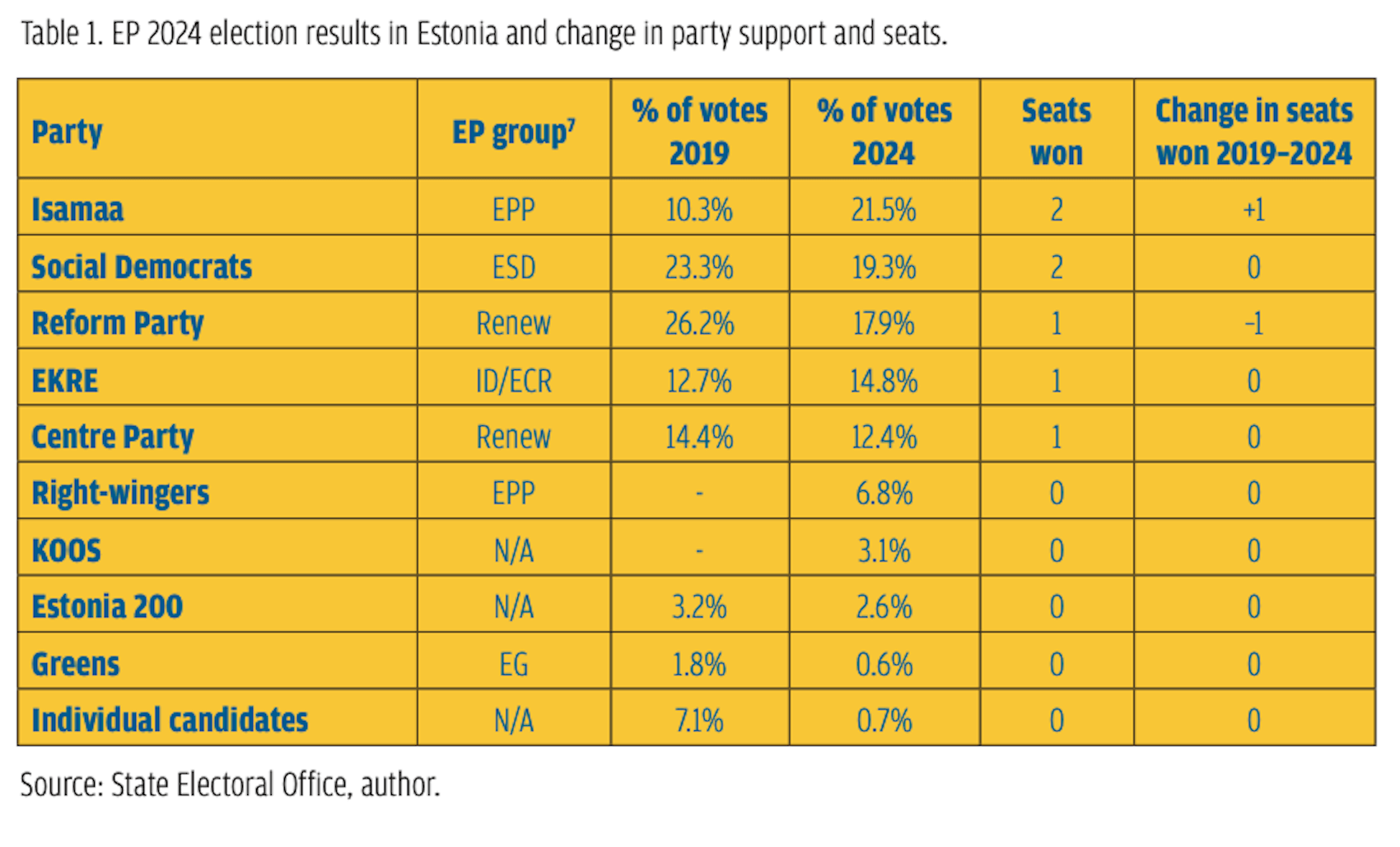

In total, Estonia elected 7 MEPs in the 2024 election, and a total of 78 candidates on 9 party lists and as individual candidates ran for the mandates. In addition to the six parties represented in the parliament (four of which were also represented in the 2019–2024 EP), four smaller parties and five individual candidates ran. However, none of the challengers managed to win a mandate.

The supply side of populism

Due to the small number of MEPs Estonia elects (just seven), EP elections in Estonia tend to be candidate-centric, where candidates compete not only concerning the ideological platforms of their parties but as individual candidates, with their personal traits and career tracks playing an important part. This tendency means EP elections are more elitist than populist, with former government ministers and foreign policy experts performing well.

In general, Estonian parties also tend to be notably pro-European integration. In 2019, only two parties, the populist radical-right EKRE (ID group) and the right-wing conservative Isamaa (EPP group), ran soft Eurosceptic campaigns (Ehin et al., 2020). In 2024, Isamaa’s campaign was somewhat less Eurosceptic (the party had meanwhile also changed its leadership), but in addition to EKRE, two new parties complemented the Eurosceptic scene, challenging EU integration and accusing it of overregulation or even harming Estonia’s national interests. Furthermore, many parties touched upon migration and asylum policy, human rights, foreign affairs and, notably, environmental policies (a significant and divisive topic in these elections). However, the main emphasis continued to be the Russia–Ukraine War and defence policy.

EKRE (still a member of the ID group during the campaign) continued to be the leading Eurosceptic party in Estonia in the 2024 EP elections, with a core pledge to maintain the EU as a union of nation-states. It called for better representation of national interests on the EU level (especially for smaller and newer member states like Estonia), ‘preserving Estonian national culture and identity from the attacks of woke-culture’ and stated that in case the EU treaties are opened for discussion, a new referendum over EU membership ought to be held (EKRE, 2024). It also challenged the EU for allegedly moving towards ideological control and suppression of individual rights, the overregulation of all domains (especially vis-à-vis the common market) and objected to introducing EU-level taxation. In addition, EKRE’s platform challenged the EU’s Green Deal as environmental extremism that favours only certain businesses and would ‘hurl majority of the people into poverty’ (Ibid). Another core policy topic in their program was immigration. The party warned that ‘immigration propaganda’ would force the public to accept ‘the rapid rise in numbers of Muslim and Eastern Slavic immigrants’ and asserted that devising immigration policy ought to be the sovereign right of nation-states. EKRE proposed returning immigrants to their countries of origin, also urging the return of Ukrainian refugees after the end of the war in order to avert a demographic crisis there.

Overall, EKRE’s campaign focused on the party’s core national–conservative ideology rather than its populist elements. The party emphasized the need to persuade the more conservative voters to participate in the EP elections, which have been, to date, dominated by more liberally minded voters (which is accurate, as liberal parties tend to perform better in the EP elections compared to national ones).

Founded in 2022 by a group of politicians expelled from the Isamaa party, the economically liberal, right-wing Parempoolsed (‘the Right-wingers’), which positioned itself as a potential member of the EPP group, is not a populist party as such (i.e., does not claim to represent the ‘real’ people) but frequently takes a decidedly anti-establishment position in claiming that the ruling elites are incompetent or not interested in dealing with pressing problems, especially from the entrepreneurs’ perspective. Hence, it somewhat resembles certain technocratic populist parties in Eastern Europe (Guasti & Buštíková, 2020). Their soft Euroscepticism also manifested in a similar genre, namely in their criticism toward overregulation, deepening integration (which can harm the interests of nation-states) and the decline in global competitiveness of the common market. In their platform titled “We protect liberty”, the Right-wingers claimed to be the ‘antidote to socialism’ proliferating in Europe (Parempoolsed, 2024). Similarly to EKRE, the party also took a critical stance toward the current EU-level environmental and immigration policy. However, it proposed different solutions, for example, emphasizing the need to attract international talent (but also keeping refugees in screening camps outside of EU borders) or supporting market-based solutions to the climate crisis. Nevertheless, as technocratic populists do more generally, The Right-wingers also emphasized its candidates’ apolitical, expert background, featuring renowned Estonian defence policy experts and entrepreneurs (among others).

Another newly established party, KOOS (Together), ran on a left-wing conservative platform, which also includes a notable pro-Russian note, especially given that the party’s chairman and only candidate in the 2024 EP elections, Aivo Peterson, is currently on trial for treason due to supporting Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. In the 2024 EP election, the party’s platform called for neutral foreign policy, strengthening international cooperation (but not mentioning with whom), dropping sanctions which they see as harmful to both the sanctioned and the sanctioning countries’ economies), but also protecting traditional family values and fostering multiculturalism. While the party did not campaign from an explicitly Eurosceptic position, the complete avoidance of even mentioning the EU in their manifesto and proposing a sovereigntist, alternative foreign policy program to Euro-Atlantic integration evidently indicates opposition to EU integration. The party’s rhetoric is notably inclusionary, as the party positions itself as the protector of the interests of ‘all Estonia’s inhabitants’, but also sets itself in a notably anti-establishment position, emphasizing that Aivo Peterson, who was in custody during the election campaign ‘demonstrates his will in practice, which does not bend under the pressure of the state.’

The right-wing conservative Isamaa (EPP group) did not run on a Eurosceptic platform per se, although it also criticized the overregulation on the EU level in passing and cited uncontrolled migration and radical Islamism as threats to the foundations of European values alongside authoritarianism and terrorism (Isamaa 2024). However, as the leading opposition party in the national parliament (according to party ratings at the time of the EP election), it took an anti-establishment stance and attempted to frame the election as a vote of confidence against the national-level ruling coalition government. It borrowed one of its election slogans, ‘Enough of false politics and deceiving people’ from an anti-establishment popular movement of 2012 (although at the time, Isamaa’s predecessor, IRL, was in government and subject to public protests). Hence, it cannot be described as a populist party par excellence, but it still utilized some of its stylistic features.

The other moderate left-wing and right-wing liberal parties (namely, the Reform Party, the Social Democrats, the Centre Party and Estonia 200) did not refer to similar Eurosceptic arguments nor emphasized policy positions that could be considered populist. Even the left-wing Centre Party, considered populist in the past (Jakobson et al., 2012), ran on a notably pro-EU integration platform and did not attempt to gain attention with populist topics. However, virtually all parties utilized populism as a performative style in their campaign tactics. According to Moffitt (2016: 8), one core aspect of populism is ‘emphasising crisis, breakdown or threat’. As a result, populists ‘perform crisis’ by ‘spectacularising failure’ and amplifying the looming threats to the level of crisis (Ibid.: 121–122). In addition to Isamaa and the Right-wingers, who campaigned under slogans like ‘Do not let yourself be deceived by those who gave baseless promises the last time’ or ‘A vote to the Social Democrats and [Marina] Kaljurand is support for the government of [Kaja] Kallas. Don’t let yourself be deceived again. Vote for Isamaa!’, the moderate and liberal parties also utilized crisis performance. For instance, candidates of the Reform Party and Social Democrats warned the voters of the ‘radicals’ who would ‘destroy Europe’s unity’ (Social Democrats) or emphasized the fragility or complexity of the security situation in which the EP elections took place (Reform Party).

The demand side of populism

With the notable exception of Indrek Tarand, who scored a mandate as an individual candidate in both 2009 and 2014, populist candidates tend not to fare very well in Estonian EP elections. While Euroscepticism is not prevalent in Estonia – 77–78% of the population supports EU membership (Eurobarometer, 2024; State Chancellery, 2024) – it thrives in certain societal segments, being associated with lower trust in government and lower levels of economic welfare. Euroscepticism is particularly concentrated in the country’s northeast, where the population is predominantly Russian-speaking (State Chancellery, 2024).

The EP 2024 results reflected the same trend, with five out of seven Estonian MEPs maintaining their mandate after the election. EKRE, which became the first Eurosceptic party in Estonia to win a mandate in EP elections in 2019, also maintained its seat, although after the elections, when an internal schism developed in the party prior to party chairman elections, their MEP Jaak Madison left the party and joined the ECR group.

Foreign, defence and security policy took central stage both in the campaigns and in public opinion, with 55% of Estonians seeing the war in Ukraine as the most important issue facing the EU at the moment, while only 15% viewed immigration as such (Eurobarometer, 2024). While economic insecurities are viewed as of the highest importance on the national level, these were not seen as relevant in EU-level politics (ibid).

While the media coverage of the campaign was relatively low-key in general (campaigning mainly took place on social media and other paid advertisements), it also did not amplify the populist messaging of the parties. Instead, the media resorted more to the moderator role, organizing numerous debates and potentially only sensationalizing the personal branding campaign of former prime minister Jüri Ratas (who ran under the Isamaa banner) on various social media channels.

The biggest winner in these elections was Isamaa, who gained a seat for Jüri Ratas (who scored in total the third-best individual result). At the same time, the Reform Party lost a seat of its incumbent MEP Andrus Ansip (also a former prime minister), who did not run in the election due to differences in opinion with the incumbent prime minister, Kaja Kallas. Overall, while the parties identified here as featuring some elements of Euroscepticism gained somewhat in their share of the popular vote, the pro-integration parties still hold the majority of seats (See Table 1).

As there are no exit polls conducted in Estonia, it is not possible to interpret the results in terms of socio-demographic or attitudinal profiles of the voters. However, what is evident from available data is that Isamaa performed best in almost all counties except for the largest cities, Tallinn and Tartu and the predominantly Russian-speaking Ida-Viru County in the northeast. Isamaa’s success has been popularly interpreted both as a result of its antigovernment campaign as well as the success of Jüri Ratas’ personal campaign. However, pre-election survey data suggests that mistrust in the Estonian government was a poor predictor of support for Isamaa and instead predicted support for KOOS and EKRE (Keerma, 2024). Furthermore, Isamaa was perceived as having ownership in defence and foreign policy by lower educated voters, while more highly educated voters perceived the Reform Party as the issue owner (ibid).

As there are no exit polls conducted in Estonia, it is not possible to interpret the results in terms of socio-demographic or attitudinal profiles of the voters. However, what is evident from available data is that Isamaa performed best in almost all counties except for the largest cities, Tallinn and Tartu and the predominantly Russian-speaking Ida-Viru County in the northeast. Isamaa’s success has been popularly interpreted both as a result of its antigovernment campaign as well as the success of Jüri Ratas’ personal campaign. However, pre-election survey data suggests that mistrust in the Estonian government was a poor predictor of support for Isamaa and instead predicted support for KOOS and EKRE (Keerma, 2024). Furthermore, Isamaa was perceived as having ownership in defence and foreign policy by lower educated voters, while more highly educated voters perceived the Reform Party as the issue owner (ibid).

EKRE also scored more votes than in 2019 in almost all counties but lost support among external voters and in the rural county of Jõgeva. Their support was largely predicted by anti-immigrant attitudes and mistrust in government (Keerma 2024). Meanwhile, the Right-wingers party scored its best results in larger towns and most likely not among populist voters, but rather more entrepreneurially minded voters who would favour a more minimal state.

Finally, KOOS performed best in regions with the highest share of Russian-speaking voters, particularly in the Ida-Viru County, where more voters are disposed to its sovereigntist foreign policy and pro-Russia messaging. In Ida-Viru County, KOOS scored 19.6% of the vote and in the capital city, Tallinn, 3.9%. Both regions feature a sizeable Russian-speaking population. The Centre Party experienced losses in all other regions except for Tallinn and Ida-Viru County, where it presumably improved its result with the Russian-speaking voters.

Also, electoral participation rose slightly. While in 2019, 332,859 voters cast a ballot, in 2024, 367,975 (37.6% of the electorate) turned out. Electoral turnout in EP elections tends to be higher in the liberal-leaning larger cities of Tallinn (the capital) and Tartu (a university town) and even lower in the predominantly Russian-speaking Ida-Viru County and the rural regions. In 2024, electoral turnout rose in all electoral districts, most notably in liberal-leaning Tartu and Tallinn.

Discussion and perspectives

As a rule, populism does not play a notable role in Estonian EP elections. Almost all parties use certain features of populist performance. However, the ideological core issues of populism, such as Euroscepticism, sovereigntism or overruling minority rights (on the populist right), do not find overwhelming support. This rule also applied in 2024, when voters still tended to prefer candidates who could be described as belonging to the political or intellectual elites and running on moderate and non-populist platforms. As a result, six out of the seven Estonian MEPs will return to Brussels and Strasbourg. Six out of seven MEPs elected in 2024 belong to the three moderate EP groups (EPP, SD and Renew) and one MEP, Jaak Madison – formerly a member of the ID group and the EKRE party in Estonia – will be joining the ECR group as an independent candidate when the parliament reconvenes. Hence, it is relatively unlikely that Estonian MEPs will engage in markedly populist politics in the EP. While the election campaign of Isamaa (EPP) involved some hints of soft Euroscepticism and anti-immigrant positions, neither of their elected MEPs has a notable track record of supporting such a policy line. Jaak Madison, who, as an ECR group member, was likely to continue his earlier anti-immigration and sovereigntist policy line, surprisingly joined the Estonian Centre Party on 22 August 2024, which may signal either a moderation of his stances or a crystallization of the soft Eurosceptic position of the Centre Party, whose members became represented both in the Renew and ECR groups.

With Madison leaving EKRE, the link between EKRE and the populist radical-right parties in the EP is likely weakened. However, with a new conservative nationalist party – the Estonian Nationalists and Conservatives – being established, it is possible that in future EP elections, Estonia will witness both candidates of the ECR as well as the PfE competing for a seat. Furthermore, the 2024 election demonstrated that there are at least two Eurosceptic pockets in the Estonian electorate – one on the radical right appealing primarily to national– conservative voters (with anti-immigrant attitudes), and another among Russian-speaking voters who favour sovereigntist, antigovernment and pro-Russia messaging, which collides with the dominant policy line of both the Estonian government and the EU. The election results in Ida-Viru County demonstrate particularly well the importance of moderate alternatives (in this case, the Centre Party) but also draw attention to the potentially harmful cocktail of low economic welfare, societal marginalization and receptiveness to Russia’s strategic narratives that sits well with populist sovereigntism.

(*) Mari-Liis Jakobson is Associate Professor of Political Sociology at Tallinn University, Estonia. Her research interests centre around populism, politics of migration and transnationalism. She is currently the PI for the project ‘Breaking Into the Mainstream While Remaining Radical: Sidestreaming Strategies of the Populist Radical Right’ funded by the Estonian Research Council, which investigates how populist radical-right parties reach out to atypical supporter groups. Her most recent publications include articles on transnational populism in European Political Science, Contemporary Politics, Journal of Political Ideologies and Comparative Migration Studies, and an edited volume, Anxieties of Migration and Integration in Turbulent Times with Springer (2023). E-mail: mari-liis.jakobson@tlu.ee

References

Auers, D. (2018). Populism and political party institutionalisation in the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 11, 341–355.

Ehin, P., & Solvak, M. (2012). Party voters gone astray: Explaining independent candidate success in the 2009 European elections in Estonia. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 22(3), 269–291.

Ehin, P., Saarts, T., & Jakobson, M. L. (2020). Estonia. The European Parliament Election of 2019 in East-Central Europe: Second-Order Euroscepticism, 83.

EKRE (2024) Eesti Eest Euroopas! EKRE programm 2024. aasta Euroopa Liidu Parlamendi valimisteks [For Estonia in Europe! EKRE’s program for the 2024 European Union Parliament elections] https://www.ekre.ee/eesti-eest-euroopas-ekre-programm-euroopa-liidu-parlamendi-valimisteks-2024/

Eurobarometer (2024). EP Spring 2024 Survey: Use your vote – countdown to the European Election. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3272

State Chancellery (2024). Avaliku arvamuse seireuuring. 18. seire, 21.-25. märts 2024 [Public opinion monitoring. 18. round, 21.-25. March 2024] https://www.riigikantselei.ee/sites/default/files/documents/2024-04/Avaliku%20arvamuse%20seireuuring%20%2821.%20-%2025.%20m%C3%A4rts%202024%29.pdf

Guasti, P., & Buštíková, L. (2020). A marriage of convenience: Responsive populists and responsible experts. Politics and Governance, 8(4), 468–472.

Isamaa (2024). Isamaa’s program for the European Parliament elections in 2024 https://isamaa.ee/ep24-program-eng/

Jakobson, M. L., Balcere, I., Loone, O., Nurk, A., Saarts, T., & Zakeviciute, R. (2012). Populism in the Baltic States. Tallinn University.

Kasekamp, A., Madisson, M. L., & Wierenga, L. (2019). Discursive opportunities for the Estonian populist radical right in a digital society. Problems of Post-Communism, 66(1), 47–58.

Keerma, K. (2024). EP valimised on välispoliitika küsimus [EP elections are a question of foreign policy] https://salk.ee/artiklid/epvalimised/

KOOS (2024). Hääl rahu eest Euroopa Parlamenti [A Vote for Peace in the European Parliament]. https://www.eekoos.ee/articles.php?n=98

Moffitt, B. (2016). The global rise of populism: Performance, political style and representation. Stanford University Press.

Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Parempoolsed (2024). Parempoolsete väärtusprogramm “Kaitseme vabadust!” [The value program of The Right “We protect liberty!”] https://parempoolsed.ee/vabadust/programm/

Petsinis, V. (2019). Identity politics and right-wing populism in Estonia: The case of EKRE. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 25(2), 211–230.

Saarts, T., Jakobson, M. L., & Kalev, L. (2021). When a right-wing populist party inherits a mass party organisation: The case of EKRE. Politics and Governance, 9(4), 354–364.

Taggart, P., & Szczerbiak, A. (2001). Parties, positions and Europe: Euroscepticism in the EU candidate states of Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 5–6). Brighton: Sussex European Institute.