In this ECPS interview, Professor Stephan Klingebiel argues that Trump-era populism signals a durable shift in global governance rather than a passing disruption. He stresses that the “rise of populism, nationalism, and right-wing populism predates Trump,” and warns that Washington is now “actively fighting all forms of multilateralism” through withdrawal, defunding, and the systematic contestation of UN language on issues such as “climate change,” “gender,” and “diversity.” Professor Klingebiel links this normative erosion to the weaponization of trade, tariffs, and development finance, which turns rules-based cooperation into coercive bargaining. He also highlights how geoeconomic competition is reshaping North–South relations by expanding bargaining space for resource-holding states. Looking ahead, he proposes a “global order minus one” as a pragmatic pathway to sustain multilateralism amid fragmentation.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In an era marked by intensified geopolitical rivalry, the resurgence of right-wing populism, and the erosion of long-standing international norms, the future of multilateral governance has become a central question for scholars and policymakers alike. In this wide-ranging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Stephan Klingebiel—Head of the Department of Inter- and Transnational Cooperation at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS)—offers a sober and incisive assessment of how Trump-era populism is reshaping global governance and what realistic alternatives may still be available.

At the heart of Professor Klingebiel’s analysis is a rejection of the notion that Trump-era populism represents a temporary aberration. Instead, he situates it within a broader and more durable constellation of political, ideological, and technological shifts. As he emphasizes, “the rise of populism, nationalism, and right-wing populism predates Trump,” extending across parts of Europe and the Global South. Trump, in this sense, is not an anomaly but a catalyst—“a prominent role” within a system that is unlikely to disappear in the near future.

A central theme of the interview is the normative and material hollowing-out of multilateralism. Professor Klingebiel argues that populism does not merely weaken international cooperation through withdrawals and defunding; it reframes cooperation itself as a zero-sum loss. In Trump’s discourse, he notes, the United States is consistently portrayed as a victim: “Canada, Europe—[they] have long lived at the expense of the United States.” This logic underpins what Klingebiel bluntly describes as an administration that is “actively fighting all forms of multilateralism.”

The interview traces how this antagonism manifests across institutions and issue areas—from the US withdrawal from dozens of international organizations to the systematic erosion of consensus-based norms within the United Nations. Particularly alarming, Klingebiel warns, is Washington’s effort to excise concepts such as “climate change, gender, gender-based violence, and diversity” from multilateral language, producing a chilling effect that leaves international organizations “no longer in a position to be explicit about real global challenges.”

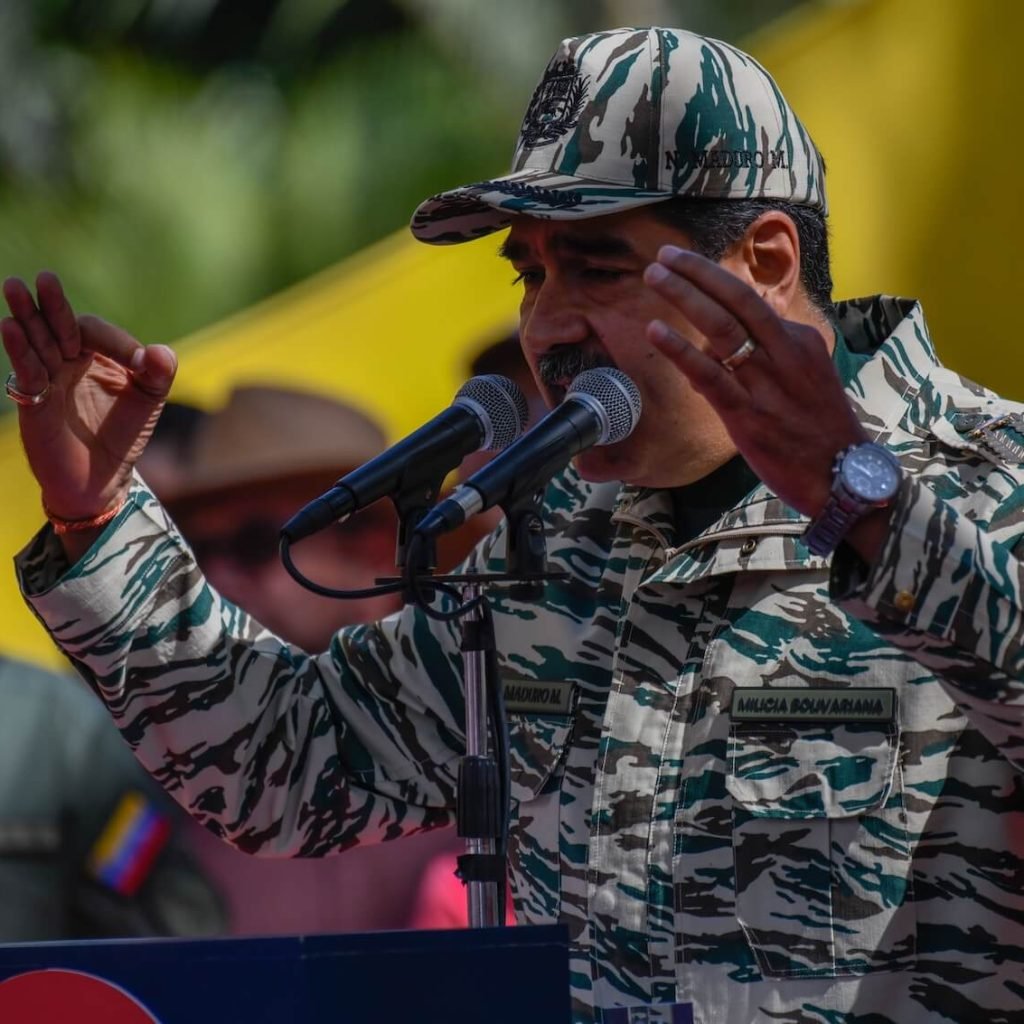

Beyond institutions, Professor Klingebiel examines the weaponization of trade, tariffs, supply chains, and development finance, describing a shift from rules-based governance to coercive bargaining. This marks, in his view, a decisive break with past practices, where even hegemonic power was at least nominally constrained by international law. Recent cases—such as US actions in Venezuela—signal a world in which legal justification is no longer even rhetorically necessary.

Yet the interview is not purely diagnostic. Looking ahead, Klingebiel introduces one of his most provocative ideas: the possibility of sustaining multilateralism through a “global order minus one.” If a broad coalition of states remains committed to multilateral norms, he argues, such an order could both isolate unilateral obstruction and create incentives for eventual re-engagement. While acknowledging that “we are most likely not going back to the situation we had five or ten years ago,” Klingebiel insists that political choices made now—particularly by Europe and like-minded partners—will decisively shape whether the future belongs to cooperative governance or competitive fragmentation.

Together, the interview offers a penetrating reflection on populism, power, and the fragile future of the international order.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Stephan Klingebiel, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

Trump-Era Populism and Global Governance

Professor Stephan Klingebiel, thank you so much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: Is Trump-era populism best understood as a temporary disruption to global governance, or does it mark a structural shift toward a new “normal” defined by transactionalism and power asymmetries? What makes such a shift durable—or reversible?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: Thank you very much for this question. It is, of course, not an easy one, as it touches on many different dimensions. To begin with, I do not think that what we are currently witnessing is something that will simply disappear in the near future. The rise of populism, nationalism, and right-wing populism predates Trump. We saw these developments earlier in parts of Europe, such as Hungary, and also in several regions of the Global South.

What we are dealing with, then, is a broader system or constellation in which Trump plays a prominent role, but he is by no means the only actor. There are numerous other political figures, institutions, and ideological currents that are unlikely to vanish any time soon. As a result, this is a reality we will probably have to contend with for the foreseeable future.

These dynamics are also connected to wider structural trends. In some parts of the world, for instance, we see growing frustration among younger generations—this is particularly evident on the African continent. At the same time, the influence of traditional media is declining, while social media is gaining prominence. Social media, in turn, has the capacity to mobilize emotions in ways that differ significantly from earlier forms of political communication. From this perspective, it is important to recognize that the impact of social media is not a temporary phenomenon, but one that is likely to remain with us for some time.

The United States Is Actively Fighting All Forms of Multilateralism

How does populism erode multilateral cooperation not only materially (through withdrawal or underfunding) but also normatively, by reframing cooperation as loss rather than collective gain?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: I think we need to emphasize that, typically—and this is true for almost all populist leaders and movements—multilateral approaches are not really part of populist political identity or thinking. It is very much the opposite. As a populist leader, you emphasize national interest and present yourself as a victim. Just listening to many speeches by President Trump, including his most recent one in Davos, we see this clearly: he portrays the United States as a victim, arguing that the rest of the world—Canada, Europe—has long lived at the expense of the United States. The conclusion, of course, is that a populist leader then seeks to turn this around and make the rest of the world pay. In this narrative, the international system is framed as fundamentally unfair to the hegemon, to the United States. In that sense, the United States is actively fighting all forms of multilateralism.

We see this in many ways. The most visible manifestations are defunding and withdrawal from international organizations. At the beginning of January this year, President Trump announced that the US would withdraw from a total of 66 international organizations. We have also already seen the defunding of a number of other international institutions to which the United States was a part.

However, what I would stress is that there are many additional ways in which the US has, over the past months, weakened—and to some extent even undermined—multilateralism. One example is the International Conference on Development Finance held last summer in Sevilla, Spain. The United States remained involved in the preparatory process until the very last moment, largely in order to slow down and weaken the negotiations and to ensure that the final outcome document would be as weak as possible. At the very end, the United States announced that it would not participate in the conference at all. In that sense, it did not show up in Sevilla. What is particularly striking, however, is that the US had already been spoiling the process before the conference and then, immediately afterward, resumed efforts to weaken the outcome document, build alliances, and contest the results of the conference.

More broadly, we can see that the United States is pursuing a range of strategies. One additional point is that, from the very beginning of the second Trump administration—in February and March 2025—the US administration has been working with a list of key terms and concepts it actively seeks to oppose. These include concepts such as climate change, gender, gender-based violence, and diversity. As soon as an international organization publishes a report or document addressing climate change or any of these other issues, the United States attempts to eliminate this kind of language and thinking.

This is particularly dangerous because, in institutions such as the United Nations—where many decisions are consensus-based—we now face a situation in which, across executive boards and institutional bodies, the United States consistently intervenes to block or dilute agreed language. For example, it seeks to replace “climate change” with terms like “extreme weather.” This practice is already shaping the internal thinking and behavior of international organizations. Increasingly, they are no longer in a position to speak openly about major global challenges. Instead, they try to avoid explicit language in order to escape constant confrontation with the United States. At the same time, the United States is actively seeking allies to challenge what was previously a broad global consensus, further eroding the normative foundations of multilateral cooperation.

We Are Entering an Era of Competing Organizations and Conflicting Norms

Are we witnessing the end of universal multilateralism, or its mutation into selective, interest-based cooperation? How does your concept of like-minded internationalism fit into this transition?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: It is probably too early to draw definitive conclusions about what kind of new era, we are entering. Much of this is still evolving. What is clear, however, is that there are very powerful forces actively trying to undermine the existing international order, most notably the United Nations. Even in the past, we saw situations in which certain actors—Russia, for example—did not accept international law in many respects, and similar patterns could be observed with other governments as well.

The key difference today, however, is that we previously had a very strong group of countries, including the United States, committed to ensuring that this international order functioned effectively. What we see now is that the United States itself is aligning with forces that are seeking to undermine—and in some cases even dismantle—this system.

Just a few days ago, President Trump publicly described the United Nations as an enemy. From this perspective, it is not difficult to understand that any international order in which the United States does not occupy a clearly dominant position is framed as contrary to American interests. The proposal of a so-called “peace council” by President Trump represents an open challenge to the United Nations. My assumption is that even if this initiative ultimately fails, and even if Trump is no longer president, the broader trend toward competing international organizations, rival groupings, and conflicting norms about the rules of the game will persist.

This brings us to the question of like-minded internationalism. On the one hand, a populist leader can seek out like-minded countries, as President Trump is doing. On the other hand, states that remain committed to multilateralism can also pursue cooperation among like-minded partners. This is something we can already observe. If you look at recent speeches in Davos—by leaders from Canada, France, and several other countries—you can see attempts to articulate collective action against the advance of right-wing populism.

At the same time, such efforts require substantial power backing to be effective. While we can see early signs of countries trying to organize this kind of counterpower, it remains a very difficult and uncertain undertaking.

We Are Seeing the Construction of a System Based on Coercive Power

Trump’s use of tariffs and trade threats as coercive tools, or as a “trade bazooka,” reflects a shift from rules-based trade to punitive bargaining. What are the long-term systemic risks of normalizing trade as a geopolitical weapon?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: We can now observe this dynamic across many policy areas. It relates to trade and tariffs, but also to foreign investment, access to critical minerals, and other domains. What is particularly new is the extent to which Trump is explicitly weaponizing all of these tools—imposing, or threatening to impose, tariffs whenever a country is deemed, from his perspective, not to be behaving in a desirable way.

One positive feature of the past was that, to a large extent, different policy areas were kept separate. If there was a conflict related to trade, it was addressed through trade instruments and negotiation. Today, this separation has largely disappeared. From a European perspective, we increasingly see that almost everything can be linked to questions about US support and positioning—for example, in relation to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine—even when the issues at stake are, in principle, unrelated.

We have seen statements suggesting that if the European Union seeks to regulate US technology companies, this could have consequences for NATO. In reality, these issues are not directly connected, but this administration is deliberately trying to weaponize all the tools at its disposal. Tariffs, in particular, appear to be one of the most immediate and effective instruments Trump can use to respond to a situation. This is deeply concerning. It signals the construction of a system based on coercive power, rather than leadership through partnership. It is no longer about win-win outcomes or cooperation, but about imposing outcomes that align with what the US leadership wants to see.

As a brief aside—and this applies to many of the points I have made—this situation strongly reflects what European countries are currently experiencing, and it is highly relevant for them. At the same time, it is important to recognize that, from the perspective of many countries and actors in the Global South, such coercion and dominance—whether by the United States or by the West more broadly—is not new. These practices have long been part of their political reality.

From a European standpoint, the liberal international order now appears to be at serious risk, and this concern is entirely justified. Yet for many countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, or Africa, experiences such as military intervention are not unprecedented. In conversations I have had over recent weeks and months, academics, political leaders, and policymakers from these regions often say: this is our normal experience as relatively small and powerless countries. US-led military interventions, particularly in Latin America over past decades, are a familiar reference point. This perspective deserves to be taken seriously.

There is also an important additional dimension. In many respects, there is truth in the argument that the international system has never been fair to large parts of the world. What is new today is that Europe and other Western countries are now feeling the impact directly, because these same coercive tools are increasingly being used against them. Yet there remains a crucial difference compared to the past. Historically, the US government—and Western governments more broadly—at least operated with a set of double standards. There were formal commitments to principles such as territorial integrity and sovereignty, and when military interventions occurred, they were typically accompanied by some form of justification grounded in international law.

If we look at events such as what happened in Venezuela in early January 2026, it was clear from the outset that there was no attempt by the US administration to justify its actions on the basis of international law. This marks a significant departure from earlier practices. In the past, Western actors were at least under pressure to frame their actions within legal justifications. Today, the United States no longer appears interested in invoking international law even as a reference point. In this sense as well, we are confronting a new situation.

Geoeconomics Has Become a Very Crucial Dimension

How does the weaponization of trade, supply chains, and development finance reshape North–South relations, particularly for countries dependent on access to Western markets and institutions?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: I think what we have already seen over the last couple of years—and this is only partly related to the second administration of President Trump, as we observed it especially during the COVID period and even before—is that we are now in a situation where supply chains, access to critical minerals, and energy security have become much more important. Geoeconomics has therefore become a very crucial dimension.

In many ways, this increasingly gives even poorer, or very poor, countries a relatively powerful bargaining instrument. Just look, for example, at the situation of a number of Sahel countries, which are now in a position to offer what they have—whether in terms of international support in United Nations General Assembly decisions or access to minerals such as uranium and other resources—to different actors: European countries, the United States, but also China and Russia, particularly when it comes to uranium.

This gives many relatively small or economically less important countries much more power at their own disposal. And this kind of multi-alignment is something that, from this perspective, is seen by many actors in the Global South—on the African continent and beyond—as a positive trend.

Greenland — Seeing Territorial Integrity Questioned Is Deeply Troubling

How should we interpret Trump’s renewed rhetoric and pressure around Greenland—symbolically and strategically? Does this signal a revival of territorial or quasi-imperial logics under populist leadership?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: This is really—especially from a European perspective—a game changer. I think what we constantly see with the Trump administration is the need to make sense of what is actually going on. There is so much happening at the same time. Some of these activities may be relevant, while others appear to be mere rhetoric or deliberate distractions. At the beginning of his second term, or even before, Trump was already using narratives about Canada, the Panama Canal, and Greenland.

Many observers initially had the impression that this was little more than window dressing—aimed at domestic audiences rather than reflecting serious intentions. However, seeing these intentions articulated so explicitly—we want to take over Greenland—and accompanied by statements that the United States would be willing to use force or military power, including reiterations of this position in Davos and elsewhere, marks a clear escalation. Announcing, over a prolonged period, that the use of military power is not excluded represents a direct challenge to international law.

This is a genuinely new dimension, and it brings us back to an era when imperial ambitions were an accepted part of international politics. From the perspective of European countries, many countries in the Global South, and the normative framework of international law, there has long been a shared hope that the territorial integrity of states would remain a foundational principle of global order. Seeing this principle openly questioned by the world’s most powerful military actor is deeply troubling.

We are therefore at a turning point, and we are still grappling with what effective responses to this new situation might look like. At the same time, this rhetoric constitutes a real threat emanating from the administration. Over the past few weeks, we have seen at least some renewed movement toward European unity. It is also important to recognize that Europe—the European Union (EU) together with the UK, and other partners—as well as countries in the Global South, are not merely in a position to wait and observe. They also have the capacity to respond.

The United States itself depends heavily on the rest of the world—for trade, access to critical minerals, and political support, among other things. In this sense, the debate around Greenland is indeed a game changer. It is likely to shape strategic concepts and political priorities for years to come.

We Can Oppose Attempts to Establish a System of Hemispheres

In a fragmented, multipolar order, are spheres-of-influence politics becoming inevitable again? For smaller and middle powers, does this create new room for maneuver—or deepen structural dependency?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: I think this is very much a concept associated with President Putin in Russia, and it seems to have been taken up by President Trump as well. If you look at the National Security Strategy from early December 2025, it reflects, more or less, exactly this kind of thinking—how the world should be organized by large powers such as the United States. In this view, regions are defined in which major powers exercise special influence, with the United States claiming its own hemisphere, understood as the Western Hemisphere.

Whether this will ultimately become the dominant way in which the world is organized remains to be seen. At the very least, however, we can observe a real risk that this kind of concept may become attractive to a number of countries.

At the same time, we need to recognize that the imperial era—when colonial powers simply ruled over other countries and territories—is quite different from today’s reality, characterized by a very different global economy. In many parts of the world, there is now an alternative understanding of how the international order should be organized. We also see significant economic and military potential in Europe and elsewhere.

So, in a sense, this intention—we want to rule our own hemisphere—is clearly present. But whether it will actually define the future organization of the international system is still uncertain. Importantly, this is also a moment in which many actors and countries are trying to push back against such ideas. European actors, for example—the European Union and the UK—have the potential to link up with partners in the Global South who are not in a weak position in many respects. So we can oppose those intentions and approaches that seek to establish a system of hemispheres.

Europe Needs the Capacity to React Within Days or Even Hour

What realistic policy alternatives exist to prevent a spiral of authoritarianism, protectionism, and institutional decay? If you had to prioritize three concrete steps for Europe, what would they be?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: I think one main challenge we need to overcome is organizing collective action. Collective action, as we know, is often difficult to organize because, within one group, there are different views and different interests. Just look at the tariff threats from the US over the past weeks and months. We saw a situation in which, for example, the interests of France, Germany, and other EU countries diverged, making it difficult to arrive at a clear, unified position.

But this is not impossible. With the Greenland escalation over the last few weeks, we saw that collective action can indeed be achieved. So, organizing collective action is crucial. A second point is that collective action among a like-minded group is a requirement—a precondition—for success. At the same time, we also need to recognize that, in certain moments, a smaller group of actors may need to provide leadership, particularly in shaping concepts and strategies.

It is also useful to consider one advantage President Trump has: as the leader in power, he can decide overnight what he wants to do. For the European Union, it is far more difficult to speak with one voice within a very limited timeframe. What this means is that Europe needs to develop the capacity to react within short periods—within days or even hours.

This kind of leadership by some European countries—without neglecting the views and interests of smaller EU members or other actors—should ensure that there is a capable, small group in a position to respond quickly. Like-mindedness is one requirement, but it must also translate into an approach that is agile in many ways: agile in terms of speed, and agile in terms of producing solutions that are ready to confront new challenges, such as political leaders openly stating their intention to take over another country.

In this regard, I think it requires a strong willingness to mobilize political, economic, and military resources, and the capacity to make decisions swiftly. These are some of my responses to your question.

A Global Order Minus One Could Become a Powerful Incentive

And finally, Professor Klingebiel, looking ahead, do you foresee a reconstitution of multilateralism, a stable equilibrium of fragmented governance, or a drift toward competitive blocs—and what political choices today will be decisive in shaping that outcome?

Professor Stephan Klingebiel: It is difficult to make any serious forecast at this point about how the world might look. However, what we have seen over the last couple of weeks is a growing discussion suggesting that we should consider—perhaps even actively push for—a global order that could be described as a “global order minus one.” This would mean that if there is a broad consensus among countries that want to uphold a multilateral approach, that want to keep the United Nations relevant—or even make it more relevant—while the United States takes a different position, it might still be possible to sustain a strong and effective form of multilateralism.

In such a scenario, we would be in a position to isolate, in many ways, what the United States is doing. Even from a conceptual perspective, this kind of global order minus one could become a powerful tool to incentivize the United States to rejoin the international consensus. If the United States were the only major player outside such an order, this would entail significant political and economic costs, as well as increased military risks for the United States itself.

What I want to emphasize is that we are most likely not returning to the situation we had five or ten years ago. Instead, we may be moving toward a different configuration in which global governance needs to be reformed in many ways—not least to incorporate rising actors from the Global South and to make the system fairer overall—but where this new arrangement could also generate substantial pressure on the United States to re-engage.

This perspective is also relevant when considering other actors that are not particularly committed to multilateralism, such as Russia. When it comes to China, the picture is somewhat different, but in all these cases, alignment remains necessary in various ways. A global order minus one may thus represent one possible pathway for navigating and potentially overcoming the difficult situation we currently face.