In-Person Programme: July 1-3, 2025. St. Cross College, Oxford University

Virtual Programme: September 2025 – April 2026 via Zoom

Between 2012 and 2024, one-fifth of the world’s democracies disappeared. During this period, “us vs. them” rhetoric and divisive politics have significantly eroded social cohesion. Yet in some instances, democracy has shown remarkable resilience. A key factor in both the rise and decline of liberal democracies is the use—and misuse—of the concept of “the people.” This idea can either unify civil society or deepen social divisions by setting “the people” against “the others.” This dichotomy lies at the heart of populism studies. However, the conditions under which “the people” become a force for democratization or a tool for majoritarian oppression require deeper, comparative, and interdisciplinary analysis. Understanding this dynamic is crucial, as it has profound implications for the future of democracy worldwide. This programme aims to foster a broad and interdisciplinary dialogue on the challenges of democratic backsliding and the pathways to resilience, with a focus on the transatlantic space and global Europe. It aims to bring together scholars from the humanities, arts, social sciences, and policy research to explore these critical issues.

Organiser

European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS)

Partners

The Humanities Division, Oxford University

Rothermere American Institute

Oxford Network of Peace Studies (OxPeace)

European Studies Centre, St Antony’s College, Oxford University

Oxford Democracy Network

Special thanks to Phil Taylor, Pádraig O’Connor, Freya Johnston, Heidi Hart, David J. Sanders, Clare Woodford, Anthony Gardner, Liz Carmichael, Harry Bregazzi, Hugo Bonin, Benjamin Gladstone, Doris Suchet, Jenny Davies, Justine Shepperson, Daniel Rowe, Katy Long, Julie Adams, Réka Koleszar, Stella Schade, Louise Lok Yi Horner, Jacinta Evans, Contestation of the Liberal Script (SCRIPTS), Network for Constitutional Economics and Social Philosophy (NOUS), and Centre for Applied Philosophy, Politics and Ethics (CAPPE).

IN-PERSON PROGRAMME

DAY ONE

(Tuesday, July 1, 2025)

Introduction

(08:45 – 08:50 / London Time)

Sumeyye Kocaman (Managing Editor, Populism & Politics, DPhil, St. Catherine’s College, Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Oxford University).

Opening Address

(08:50 – 09:20 / London Time)

Kate Lyndsay Mavor, CBE (Master of St Cross College, Oxford University).

Janet Royall (Baroness Royall of Blaisdon, Principal of Somerville College, Oxford University).

Roundtable -I-

(09:20 – 11:00 / London Time)

Politics of the ‘People’ in Global Europe

Chair

Jonathan Wolff (Senior Research Fellow in Philosophy and Public Policy, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford; President of the Royal Institute of Philosophy).

Speakers

“The Reappearance of ‘The People’ in European Politics,” by Martin Conway (Professor of Contemporary European History, University of Oxford).

“The Construction of the Reactionary People,” by Aurelien Mondon (Professor of Politics, University of Bath).

“Christianity in A Time of Populism,” by Luke Bretherton (Regius Professor of Moral & Pastoral Theology, University of Oxford).

Coffee Break

(11:00 – 11:30)

Panel -I-

(11:30 – 13:00 / London Time)

Politics of Social Contract

Chair

Lior Erez (Alfred Landecker Postdoctoral Fellow, Blavatnik School of Government, Nuffield College, Oxford University).

Speakers

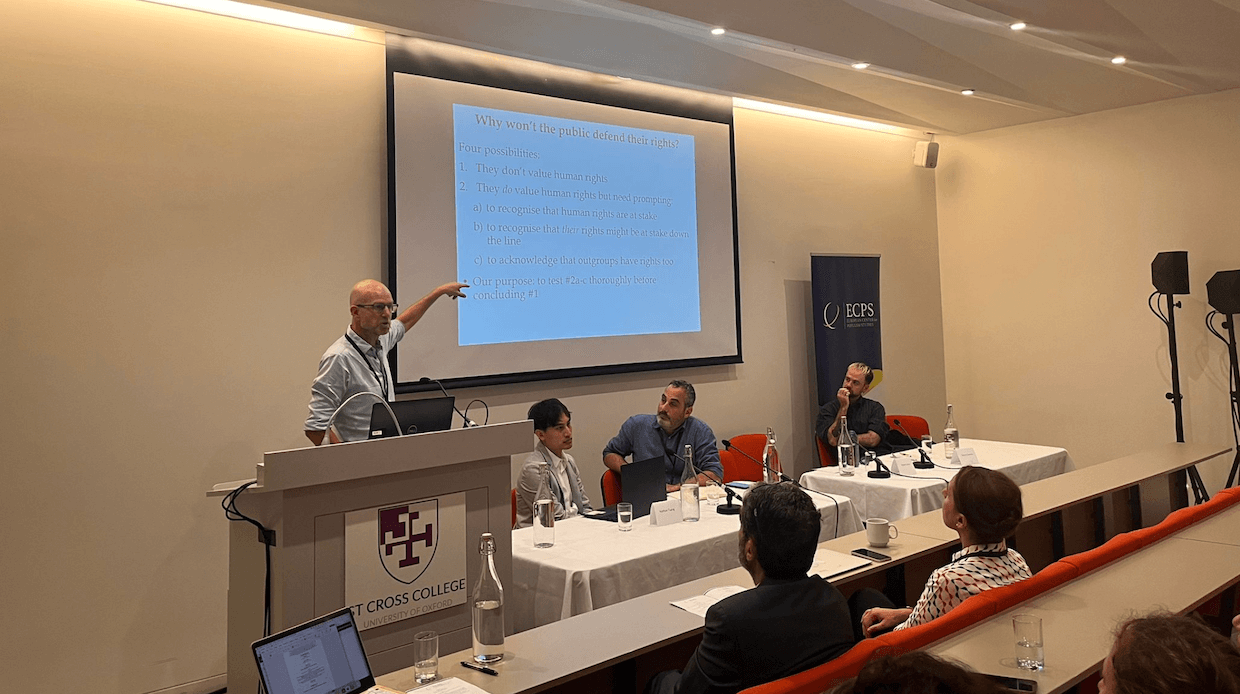

“Exploring Human Rights Attitudes: Outgroup Perception and Long-term Consequences,’ by Sabine Carey (Professor of Political Science at the University of Mannheim and Director of the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research); Robert Johns (Professor of Politics at the University of Southampton), Katrin Paula (Postdoctoral Researcher, Technical University Munich) and Nadine O’Shea (Postdoctoral researcher, Technical University Munich).

“Doing Politics Non-politically: Explaining How Cultural Projects Afford Political Resistance,” by Nathan Tsang (Doctoral Candidate in Sociology, University of Southern California).

“From Demos to Cosmos: The Political Philosophy of Isabelle Stengers,” by Simon Clemens (Doctoral Researcher at the Cluster of Excellence “Contestation of the Liberal Script – (SCRIPTS)” and at Theory of Politics at Humboldt Universität zu Berlin).

Lunch

(13:00 – 14:00)

Panel -II-

(14:00 – 15:30 / London Time)

‘The People’ in the Age of AI and Algorithms

Chair

Alina Utrata (Career Development Research Fellow, Rothermere American Institute, St John’s College, Oxford University).

Murat Aktaş (Professor, Political Science Department, Muş Alparslan University).

Speakers

“Navigating Digital Disruptions: The Ambiguous Role of Digital Technologies, State Foundations and Gender Rights,” by Luana Mathias Souto (Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow, GenTIC Research Group, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya).

“The Role of AI in Shaping the People: Big Tech and the Broligarchy’s Influence on Modern Democracy,” by Matilde Bufano (MSc in International Security Studies, Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies and the University of Trento).

Coffee Break

(15:30 – 16:00)

Panel -III-

(16:00 – 18:00 / London Time)

Populist Threats to Modern Constitutional Democracies and Potential Solutions: Research Output of the Jean Monnet Chair EUCODEM

Co-Chairs

Elia Marzal (Associate Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Barcelona).

Bruno Godefroy (Associate Professor in Law and German, University of Tours, France).

Speakers

“Theoretical Foundations of Modern Populism: Approaches of Heidegger, Laclan and Laclau,” by Daniel Fernández (Assistant Professor of Constitutional Law, Universitat Lleida).

“Erosion of the Independence of the Judiciary,” by Marco Antonio Simonelli (Assistant Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Barcelona).

“Referenda as a Biased and Populist Tool: Addressing a Complex Issue in a Binary Way,” by Elia Marzal (Associate Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Barcelona).

“Pro-Independence Movements as A Populist Way Out in Multinational Contemporary Societies,” by Núria González (Assistant Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Barcelona).

“Potential Solutions: Second Chambers, Demos and Majoritarian Body,” by Roger Boada (Assistant Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Barcelona).

Drinks Reception

(18:15-19:00 — Common Room)

Dinner

(19:00-21:00 — Dining Hall)

DAY TWO

(Wednesday, July 2, 2025)

Panel -IV-

(09:00-10:30 / London Time)

Politics of Belonging: Voices and Silencing

Chair

Azize Sargın (PhD., Director of External Relations, ECPS).

Speakers

“The Scents of Belonging: Olfactory Narratives and the Dynamics of Democratization,” by Maarja Merivoo-Parro (Marie Curie Fellow, University of Jyväskylä).

“Silent Symbols, Loud Legacies: The Child in Populist Narratives of Post-Communist Poland,” by Maria Jerzyk (Graduate student, Masaryk University in Brno, Czechia).

Coffee Break

(10:30-11:00)

Roundtable -II-

(11:00 – 12:30 / London Time)

‘The People’ in and against Liberal and Democratic Thought

Chair

Aviezer Tucker (Director for the Centre for Philosophy of Historiography and the Historical Sciences, University of Ostrava).

Speakers

“Listening to ‘the People’: Impossible Concepts in Political Philosophy,” by Naomi Waltham-Smith (Professor, Music Faculty, University of Oxford).

“Liberal Responses to Populism,” by Karen Horn (Professor in Economic Thought, University of Erfurt) & Julian F. Müller (Professor of Political Philosophy, University of Graz).

“The Living Generation – A Presentist Conception of the People,” by Bruno Godefroy (Associate Professor in Law and German, University of Tours, France).

Lunch

(12:30 – 13:30)

Panel -V-

Governing the ‘People’: Divided Nations

(13:30 – 15:00 / London Time)

Co-Chairs

Leila Alieva (Associate Researcher, Russian and East European Studies, Oxford School of Global and Area Studies, Oxford).

Karen Horn (Professor in Economic Thought, University of Erfurt).

Speakers

“Catholicism and nationalism in Croatia: The Use and Misuse of ‘Hrvatski Narod’,” by Natalie Schwabl (Doctoral Candidate, Faculty of Arts, Languages, Literature and Humanities, Sorbonne University).

“‘Become Ungovernable:’ Covert Tactics, Racism, and Civilizational Catastrophe,” by Sarah Riccardi-Swartz (Assistant Professor of Religion and Anthropology, Northeastern University).

“Is There Left-wing Populism Today? A Case Study of the German Left and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance,” by Petar S. Ćurčić (Research Associate, Institute of European Studies, Belgrade).

Coffee Break

(15:00 – 15:30)

Panel -VI-

The ‘People’ in Search of Democracy

(15:30 – 17:00 / London Time)

Chair

Max Steuer (Principal Investigator at the Department of Political Science of the Comenius University in Bratislava).

Speakers

“Between Antonio Gramsci and Erik Olin Wright: Deepening Democracy through Civil Society Engagement,” by Rashad Seedeen (Adjunct Research Fellow in the Department of Politics, Philosophy and Media in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, La Trobe University, Melbourne).

“Resilient or Regressive? How Crisis Governance Reshapes the Democratic Future of ‘The People’,” by Jana Ruwayha (PhD Candidate, Faculty of Law; Teaching and Research Assistant, Global Studies Institute; University of Geneva).

“The Performative Power of the ‘We’ in Occupy Wall Street and Gezi Movement,” by Özge Derman (PhD., Sciences Po and Sorbonne University).

DAY THREE

(Thursday, July 3, 2025)

Coffee

(09:00 – 09:30)

Panel -VII-

(09:30 – 11:00 / London Time)

‘The People’ in Schröndinger’s Box: Democracy Alive and Dead

Co-Chairs

Ming-Sung Kuo (Reader in Law, University of Warwick School of Law).

Bruno Godefroy (Associate Professor in Law and German, University of Tours, France).

Speakers

“The Matrix of ‘Legal Populism’: Democracy and (Reducing) Domination,” by Max Steuer (Principal Investigator, Department of Political Science, Comenius University).

“Lived Democracy in Small Island States: Sociopolitical Dynamics of Governance, Power, and Participation in Malta and Singapore,” by Justin Attard (PhD Candidate, University of Malta).

“Russia’s War on Democracy,”by Robert Person (Professor of International Relations and Director of curriculum in International Affairs, United States Military Academy).

Coffee Break

(11:00 – 11:30)

Panel -VIII-

(11:30 – 13:30 / London Time)

‘The People’ vs ‘The Elite’: A New Global Order?

Co-Chairs

Ashley Wright (Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Minerva Global Security Programme, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford).

Azize Sargın (PhD., Director of External Relations, ECPS).

Speakers

“We: The Populist Elites,” by Aviezer Tucker (Director for the Centre for Philosophy of Historiography and the Historical Sciences, University of Ostrava).

“Reclamations of ‘We, the People’: Rethinking Civil Society through Spatial Contestations in Turkey,” by Pınar Dokumacı (Assistant Professor at the School of Politics and International Relations, University College Dublin) & Özlem Aslan(Assistant Professor in the Core Program at Kadir Has University).

“The Transatlantic Network of Authoritarian Populism: The Rise of the Executive and Its Dangers to Democracy,” by Attila Antal (Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, Institute of Political Science, Eötvös Loránd University).

“The French New Right and Its Impact on European Democracies,” by Murat Aktaş (Professor, Political Science Department, Muş Alparslan University); Russell Foster (Senior Lecturer in British and International Politics, King’s College London, School of Politics & Economics, Department of European & International Studies).

Discussant

Karen Horn (Professor in Economic Thought, University of Erfurt).

Lunch

(13:30 – 14:30)

Roundtable -III-

(14:30 – 16:00 / London Time)

When the Social Contract Is Broken: How to Put the Genie Back

Co-Chairs

Irina von Wiese (Honorary President of ECPS).

Selçuk Gültaşlı (Chairperson, ECPS Executive Board).

Speakers

Aviezer Tucker (Director for the Centre for Philosophy of Historiography and the Historical Sciences, University of Ostrava).

John Thomas Alderdice (Baron Alderdice of Knock, in the City of Belfast, Founding Director of the Conference on the Resolution of Intractable Conflict, Oxford University; Founder of the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building).

Julian F. Müller (Professor of Political Philosophy, University of Graz).

Closing Remarks

(16:00 – 16:10 / London Time)

Irina von Wiese (Honorary President of ECPS).

Biographies & Abstracts

Irina von Wiese is the Honorary President of the ECPS. She was born in Germany, the daughter and granddaughter of Polish and Russian refugees. After completing her law studies in Cologne, Geneva, and Munich, she secured a scholarship to study for a master’s degree in public administration at the Harvard Kennedy School. Her subsequent legal training took her to Berlin, Brussels, and Bangkok, providing her with initial insight into the plight of refugees and civil rights defenders worldwide. From 1997 to 2019, Irina lived and worked as a lawyer in both private and public sector roles in London. During this period, she volunteered for human rights organisations, advising on migration policy and welcoming refugees into her home for many years.

In 2019, Irina was elected to represent the UK Liberal Democrats in the European Parliament. She served as Vice Chair of the Human Rights Subcommittee and as a member of the cross-party Working Group on Responsible Business Conduct. The Group’s main achievement was the introduction of EU legislation that made human rights due diligence mandatory in global supply chains. During her term, she was also elected to the Executive Committee of the European Endowment for Democracy, which supports grassroots civil society initiatives in fragile democracies.

Having lost her seat in the European Parliament after the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union, Irina returned to the UK, where she was elected to the Council of Southwark, one of London’s most diverse boroughs. Her links to Brussels are maintained through an advisory role at FGS Global, where she works on EU law and ESG issues. In addition, Irina is an Affiliate Professor at the European Business School, the ESCP, teaching international law and politics (including a course entitled ‘Liberalism and Populism’). Irina is the proud mother of a teenage daughter.

Roundtable -I-

Politics of the ‘People’ in Global Europe

Jonathan Wolff is a Professor at the Blavatnik School, University of Oxford, and President of the Royal Philosophical Society. He is a Senior Research Fellow in Philosophy and Public Policy and a Supernumerary Fellow at Wolfson College. He was formerly the inaugural Alfred Landecker Professor of Values and Public Policy, having been appointed Blavatnik Chair in Public Policy at the School in 2016. Before joining Oxford, Jo was Professor of Philosophy and Dean of Arts and Humanities at UCL. He is a political philosopher who works on questions of inequality, disadvantage and social justice. He has published a book, City of Equals (OUP 2024), co-authored with Avner de-Shalit. His work in recent years has also turned to applied topics such as public safety, disability, gambling, and the regulation of recreational drugs, which he has discussed in his books Ethics and Public Policy: A Philosophical Inquiry (Routledge 2011, second edition 2019) and The Human Right to Health (Norton 2012). His “An Introduction to Moral Philosophy” and an associated edited volume, “Readings in Moral Philosophy,” were published by W. W. Norton in 2018, with new editions forthcoming in 2024. Earlier works include Disadvantage (OUP 2007), with Avner de-Shalit; An Introduction to Political Philosophy (OUP, 1996, fourth edition 2023); Why Read Marx Today? (OUP 2002); and Robert Nozick (Polity 1991), together with several edited collections. His recent work has also explored social equality, poverty, and social exclusion, as well as methodological issues in political philosophy. He is now working on questions of belonging, nationalism, and civil society.

Martin Conway is a Professor of Contemporary European History at Balliol College, University of Oxford. His research has primarily focused on European history from the 1930s to the final decades of the twentieth century. Over the last few years, much of his work has focused on the history of Democracy in twentieth-century Europe. He has published numerous articles on the nature of democracy in post-war Europe and authored a large book, entitled Europe’s Democratic Age: Western Europe 1945-68, with Princeton University Press in the spring of 2020. He is continuing to write about democracy and is completing a collaborative project on the history of Social Justice in twentieth-century Europe. He has also begun a new project on Political Men, which seeks to problematise the forms of male political citizenship which have developed in Europe across the twentieth century. Its focus is consciously comparative, embracing a variety of political regimes and periods. Its underlying thesis is that we need to understand how male forms of political action have had a significant influence on the evolution of both democratic and non-democratic regimes. He also has a strong interest in the concept of the History of the Present, as a distinct era separate from the more familiar span of the twentieth century. He is one of the editors (with Celia Donert and Kiran Patel) of a new book series published by Cambridge University Press, entitled European Histories of the Present.

Aurelien Mondon (he/him) is a Professor of Politics at the University of Bath , specialising in politics, and co-convenor of the Reactionary Politics Research Network. His research focuses predominantly on the impact of racism and populism on liberal democracies and the mainstreaming of far-right politics through elite discourse. His first book, The Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right in France and Australia: A Populist Hegemony? was published in 2013, and he recently co-edited After Charlie Hebdo: Terror, racism and Free Speech, published with Zed. Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream, co-written with Aaron Winter, was published by Verso in 2020. The Ethics of Researching the Far Right, co-edited with Antonia Vaughan, Joan Braune, and Meghan Tinsley, was published in April 2024 by Manchester University Press. His work has been published in various mainstream and expert outlets worldwide, including CNN, The Guardian, The Independent, Libération, Newsweek, Le Soir, Mediapart and Al Jazeera.

Luke Bretherton is Regius Professor of Moral & Pastoral Theology, University of Oxford. Before Oxford, Bretherton was the Robert E. Cushman Distinguished Professor of Moral and Political Theology and Senior Fellow of the Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University. Before joining Duke in 2012, he was Reader in Theology & Politics and Convener of the Faith & Public Policy Forum at King’s College London. Alongside his scholarly work, he writes in the media on topics related to religion and politics, has worked with a variety of faith-based NGOs, mission agencies, and churches around the world, and has been actively involved over many years in forms of grassroots democratic politics, both in the UK and the US. He also hosts the Listen, Organize, Act! podcast which focuses on the history and contemporary practice of community organizing and the role religion plays in democracy. Specific issues addressed in his work include debt, fair trade, environmental justice, racism, humanitarianism, the treatment of refugees, interfaith relations, euthanasia, secularism, nationalism, church-state relations, and the provision of social welfare.

M. Isabel Garrido Gómez is Titular Professor in Legal Philosophy at the University of Alcalá (Spain) and Director Chair for Democracy and Human Rights, University of Alcalá and Spanish Ombudsman. She is author of Family Policy in the European Union 2000 (Madrid: Dykinson); Criterions for Solution of Interests in Private Law 2002 (Madrid: Dykinson); Rudolf von Stammler´s Theory and Philosophy of Law 2003 (Madrid: Reus)”; Fundamental Rights and Social and Democratic Rule of Law 2007 (Madrid: Dilex); The Law as Normative Process, in collaboration 2007 (Alcalá de Henares (Madrid): University of Alcalá Press); Equality in the Law and in the Application of Law 2009 (Madrid: Dykinson); The Changes of Law in the Global Society 2010 (Navarra: ThomsonAranzadi); Democracy in the Legal Sphere 2013 (Madrid: Civitas); The Function of Judges: Context, Activities and Tools 2014 (Navarra: Aranzadi); (as traslator), in collaboration, Law without True 2005 (Madrid: Dykinson); (as coordinator), with , The Right of Child to Live in his/her Family 2007 (Madrid: Exlibris); (as editor), in collaboration, Social Rights as a Requirement of Justice 2009 (Alcalá de Henares (Madrid): University of Alcalá Press and Spanish Ombudsman); (as editor), in collaboration, Ideological Liberty and Conscientious Objection 2011 (Madrid: Dykinson); (as editor), The Right to Peace as an Emergent Right 2011; (as editor), The Human Right to Development 2013 (Madrid: Tecnos); (as editor), The Efectiveness of Social Rights 2013 (Madrid: Dykinson); (as co-editor), Democracy, Governance, and Participation 2014 (Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch); in collaboration Challenges and Paradoxes of Constitutional Democracy 2014 (Granada: Comares).

Roundtable -II-

‘The People’ in and against Liberal and Democratic Thought

Naomi Waltham-Smith is a Professor at the Music Faculty, University of Oxford. Specializing in the politics of listening, she is an interdisciplinary scholar working at the intersection of philosophy (especially recent French, Black radical, and decolonial thought) with music and sound studies. She is interested in how aurality is imbricated in some of the most significant and urgent political issues under contemporary capitalism, including the crises of democracy we are witnessing today, together with antiracist and environmental struggles. She has also worked on the politics of listening in contexts as varied as the Austro-German musical canon and Las Vegas casinos. Beyond academic publication, she works collaboratively in the public sphere to develop these ideas through listening workshops and citizens’ assemblies, multimedia installations in galleries and public spaces, long-term community collaborations, and policy engagement. Prior to joining Oxford in September 2023, she was Professor in the Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodologies and Deputy Chair of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Warwick, where she was also Chair of the Academic Freedom Review Committee. Before that she taught Music and Comparative Literature at the University of Pennsylvania (2012–2018), having held postdoctoral fellowships at City University and Indiana University, and supervised at the University of Cambridge. She is a graduate of Selwyn College, Cambridge and King’s College London.

Karen Horn is a business journalist, publicist and university lecturer. Horn studied economics at Saarland University and the University of Bordeaux III and received her doctorate from the University of Lausanne. From 1995 to 2007, she was a member of the economics editorial team of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. There, she wrote about regulatory policy issues and economics as a science. She was the editor in charge of the page Die Ordnung der Wirtschaft and responsible for the reviews of economics books. From October 2007 to the end of March 2012, she was head of the capital city office of the German Economic Institute in Berlin. From April 2012 to 2013, she was Managing Director of Wert der Freiheit gGmbH, founded by Theo Müller and Thomas Bachofer, Chairman of the Board of Sachsenmilch AG. Horn teaches as a lecturer at the HU Berlin, the University of Witten/Herdecke, the University of Siegen and the Faculty of Political Science at the University of Erfurt. She was appointed honorary professor at the University of Erfurt in 2019. She writes regularly for the debate magazines Standpoint and Schweizer Monat and occasionally for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

Julian F. Müller is a Professor of Political Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Graz. His main areas of research are political philosophy and applied ethics. In political philosophy, his work focuses on the themes of reasonable and unreasonable political disagreements. In his book, Political Pluralism, Disagreement, and Justice(Routledge 2019), he develops the concept of Polycentric Democracy, a set of institutions designed to promote justice in the face of widespread disagreements about facts and norms. The book received the Werner von Melle and Roman Herzog Prizes. In more recent work, he has explored unreasonable disagreements, formulating an epistemic theory of populist ideology. Currently, he is investigating the systematic role of the concept of truth in theories of classical liberalism. In applied ethics, he has published on topics including migration ethics, the ethics of emerging technologies, and economic ethics.

Bruno Godefroy is an associate professor in Law and German at the University of Tours (France). His research focuses on constitutional theory, political philosophy, and the history of ideas. Recent publications: “Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology: Legitimizing Authority after Secularization,” Political Theory 53/1 (2025), “Karl Löwith’s Historicization of Historicism” (in H. J. Paul, A. van Veldhuizen (ed.), Historicism: A Travelling Concept, London, Bloomsbury, 2021), La Fin du sens de l’histoire. Eric Voegelin, Karl Löwith et la temporalité du politique (Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2021).

Roundtable -III-

When the Social Contract Is Broken: How to Put the Genie Back

Selcuk Gultasli is the chairperson of ECPS’s executive board. Mr. Gultasli is responsible for the operations of both the ECPS’s academic group and administrative staff. Mr. Gultasli was previously the Brussels Bureau Chief of Zaman daily until the Turkish government confiscated the newspaper on March 4, 2016. He is interested in EU policy, especially expansion, and has written extensively on the EU and the potential expansion process. He also studies Turkish accession to the EU, human rights, rule of law, liberal democracy, Turkish-Kurdish relations, and the history of Armenian-Turkish relations. Mr. Gultasli graduated from Boğaziçi University in 1991; he continued his studies at Middle East Technical University, earning his M.A. with a thesis on the comparison of Turkish dailies in relation to EU membership discussions. He obtained another M.A. degree from the Catholic University of Leuven; he wrote his thesis on the comparison of English and French secularism. Concerned about the rise of illiberal democracies in many democratic countries, Gultasli thinks it is of the utmost importance to study the rise of populism and populist leaders.

Lord John Alderdice has an academic and professional background in medicine, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis. He is the founding Director of the Conference on the Resolution of Intractable Conflict, based in Oxford and with colleagues in Belfast he also established the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building which continues work on the implementation of the principles of the Good Friday Agreement and takes the lessons of the Irish Peace Process to other communities in conflict. More recently, he set up The Concord Foundation with a wider remit in understanding and addressing the nature of violent political conflict and its resolution. Lord Alderdice’s work has been recognised throughout the world with many fellowships, visiting professorships, honorary doctorates, and international awards. Having been appointed to the House of Lords in 1996, he was elected Convenor of the Liberal Democrats for the first four years of the Liberal/Conservative Coalition Government from 2010 to 2014. His international interests had previously led to his election as President of Liberal International, the global network of some 100 liberal political parties and organisations. He served from 2005 to 2009 and remains an active Presidente D’Honneur.

He was a consultant psychiatrist and Senior Lecturer at The Queen’s University of Belfast, where he established the Centre for Psychotherapy with various degree courses, research work and clinical services. He also devoted himself to understanding and addressing religious fundamentalism and long-standing violent political conflict, initially in Ireland, and then in various other parts of the world. This commitment took him into politics, and he was elected Leader of Northern Ireland’s Alliance Party from 1987 to 1998, playing a significant role in the negotiation of the 1998 Belfast/Good Friday Agreement. When the new Northern Ireland Assembly was elected, he became its first Speaker. In 2004, he retired from the Assembly on being appointed by the British and Irish Governments as one of the four members of the Independent Monitoring Commission (IMC), appointed to close down the operations of the paramilitary organisations (2003-2011). He continued with this work on security issues when the new Northern Ireland Government commissioned him and two colleagues to produce a report advising them on a strategy for disbanding the remaining paramilitary groups (2016).

Julian F. Müller is a Professor of Political Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Graz. His main areas of research are political philosophy and applied ethics. For more info, see page 18-19.

Panel -I-

Politics of Social Contract

Exploring Human Rights Attitudes: Outgroup Perception and Long-term Consequences

Sabine Carey is Professor of Political Science at the University of Mannheim and Director of the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research. She empirically investigates drivers of different forms of state-sponsored violence, with particular emphasis on the role of political institutions and repressive agents. She is interested in understanding what drives people’s perceptions of peace, security and human rights. Her work has been supported by research grants from the German Science Foundation and the European Research Council, among others.

Robert Johns is Professor of Politics at the University of Southampton. He has twenty years’ experience of research and teaching in the fields of elections, public opinion, political psychology and survey methodology. He is interested in what people think about politics, where those opinions come from, and how we can go about measuring slippery things like beliefs, attitudes and values. Rob has worked on a large number of (often ESRC-funded) survey projects, most notably as a founding investigator on the Scottish Election Study series, and has particular expertise in the design of survey experiments.

Katrin Paula is Professor of Global Security and Technology at the Technical University Munich. She researches and teaches in the field of Human Security and Contentious Politics. A particular focus of her work is how changing information- and communication technologies and their strategic use and control affect political mobilization and violence. Exemplary research areas include the effect of information technologies on the spatial and temporal diffusion of protests, the effect of state censorship on political attitudes, or the strategic use of violence during elections, as well as methods of data collection in the field of conflict studies and statistical modeling of spatial processes.

Nadine O’Shea is a postdoctoral researcher, working with Katrin Paula and Sabine Carey in the DFG project “Security threats and fragile commitments: Stress-testing German support for human rights at home and abroad” at the Technical University Munich since November 2023. Nadine specializes in conducting empirical research within the field of peace and conflict studies, specifically focusing on human rights, civil wars, and foreign policy. She also has a keen interest in research methods. During her Bachelor’s degree in ‘International Relations (B.A.)’ at Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences in Kleve, Nadine completed an internship abroad at the Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany to the United Nations in New York and a semester abroad at San Diego State University. In her Master’s degree ‘Political Science with a specialisation in conflicts, power, and politics (MSc.)’ at Radboud University, in the Netherlands, she focused on the research areas of democratisation, populism and peace and conflict research. By participating in the Radboud Honours Academy and completing a research internship, her interest in research grew. From 2018 to 2023, Nadine worked as a research assistant at the University of Greifswald, where she taught introductory and research practice seminars on international relations. Nadine also taught Quantitative Methods at the University West in Sweden as part of the Erasmus programme. In November 2023, Nadine submitted her dissertation entitled ‘External Interference and Violence Against Civilians During Civil Wars’ to the University of Greifswald.

Abstract: People are often willing to embrace rights-restricting policies, particularly if this is seen as necessary to maintain security or to restrain an out-group. These policies are typically framed as security benefits. What happens when the public is prompted to consider the human rights costs – and the possibility that restricting an out-group today might be applied to an in-group tomorrow? Research in this field has rarely tested public responsiveness to an explicit defence of human rights. To shed new light on this, we address two related questions: What arguments can strengthen support for human rights of others? How much does the answer to this question depend on people’s attitudes towards those whose rights are affected? With a novel survey experiment of over 6,000 adults in Germany, we find that highlighting human rights violations does not in general sway people’s opinions about amnesty for excessive police violence. But it does make respondents less supportive of such amnesty when they would be least committed to human rights. Our study paints an optimistic picture that a stronger human rights narrative might reach those who are otherwise least committed to human rights.

Doing Politics Non-politically: Explaining How Cultural Projects Afford Political Resistance

Nathan Tsang is a third-year Ph.D. student in sociology at the University of Southern California. His research interests include cultural sociology, political sociology, and social movement studies, with a focus on the connections and disconnections between culture and politics in everyday situations. He has published on Hong Kong’s fact-checking activism in journalism and journalism studies, as well as on online incivility in social movements in computational communication research and the politics of language in Hong Kong. His forthcoming co-authored book chapter in the Handbook of Hong Kong Studies (published by Brill) discussed how different place configurations inform various conceptualisations of “Hong Kong diaspora.” He currently uses qualitative methods to investigate the cultural preservation projects of Asian immigrants in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Abstract: While the literature on repression, diaspora, and resistance substantially enriches our understanding of how individuals resist secretly and creatively under political pressure, it is still unclear how political resistance survives in nonpolitical organizations. This question is crucial to diasporic migrants from autocratic countries who cannot engage in formal mobilization and use nonpolitical organizations to preserve their collective solidarity. Empirically, this study draws on 18 months of ethnographic fieldwork in two cultural organizations by diasporic Hongkongers in the United States. It argues that by comparing two forms of cultural preservation projects—one emphasizing cultural artifacts and another focusing on communal gatherings—collective resistance can exist in organizational life without being deliberately political. Contrary to conventional logic, resistance in the Hong Kong case was neither disguised nor individualized but diffused in cultural activities. To accomplish this, people developed patterned ways to cue political speeches with the help of objects in the physical settings of cultural events. Relying on objects’ material affordances, organizers can regulate political speeches in activities, whereas participants can momentarily shift their speeches into political expressions. As such, organization members can consistently cue a sense of political resistance within their nonpolitical activities. I call this reliance on object-mediated interactions to articulate political concerns “afforded politicization.” The findings contribute to the scholarship by answering the question of when and how isolated, covert forms of everyday resistance can become politically meaningful in organizational life. By showing that diasporic cultural practices are a form of everyday resistance, the study argues that repressed people can mediate politics using objects, and with enough object-mediated interactions, individual resistance can aggregate into collective resistance.

From Demos to Cosmos. The Political Philosophy of Isabelle Stengers

Simon Clemens is a doctoral researcher at the Cluster of Excellence “Contestation of the Liberal Script – (SCRIPTS)” and doctoral student at Humboldt Universität zu Berlin (Theory of Politics). Following a research stay at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, he is currently a research fellow at Brown University. In addition, he is a freelance contributor to the Federal Agency for Civic Education and the German Resistance Memorial Museum. In his dissertation, he examines the concept of democracy within the debate of New Materialism. His research interests include hegemony and democratic theories, (new and old) materialisms, memory culture, resistance and protest movements, environmental humanities, and (theories of) education.

Abstract: Politics, when considering all beings—human and nonhuman—faces challenges in addressing this multiplicity. As climate and ecological crises reveal our mutual interdependence, the need for new democratic models is pressing, yet such political visions remain rare. Cosmopolitics, a concept proposed by Belgian philosopher Isabelle Stengers, offers a way to address this gap by expanding democracy beyond human concerns to include all beings, imagining new forms of collectivity.

Stengers’ cosmopolitics challenges the conventional focus on consensus and antagonism in democracy, presenting a “third way” beyond liberal, deliberative, and populist approaches. The paper unfolds in three parts: first, I contrast Stengers’ approach to heterogeneity with John Rawls’ notion of plurality, introducing her concepts of “ecology of practice” and “cosmopolitics” as alternatives to consensus-based coexistence. While Stengers addresses a problem common to liberal democratic theory, her solution and analysis diverge significantly, offering a distinct perspective. Second, I explore how Stengers’ proceduralism—focused on process rather than consensus—enables a common world without requiring agreement. Unlike Jürgen Habermas’ deliberative proceduralism, which excludes non-communicative beings, Stengers’ approach seeks coexistence without consensus, critiquing the limitations of traditional liberal frameworks. Lastly, I examine Stengers’ ecological framing and the figure of the diplomat, offering a path for pacifying antagonistic relations. Her cosmopolitics seeks to balance democracy with ecological awareness, proposing an inclusive model that avoids the coercion of both consensus and populism.

Panel -II-

The “People” In the Age of AI and Algorithms

Alina Utrata is a Career Development Research Fellow at St John’s College, University of Oxford, an associate member of the Department of Politics and International Relations and a fellow at the Rothermere American Institute. Her research examines technology corporations beyond the traditional political/economic divide, theorizing how and when corporations may enact a kind of political power, from cloud computing to digital payment systems. She received her PhD in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge and was a 2020 Gates-Cambridge Scholar, where her thesis was awarded the Lisa Smirl PhD Prize.

In addition to her doctoral research, she has published in the American Political Science Review and the Boston Review comparing Silicon Valley’s outer space colonization projects with the histories of colonizing corporations such as the British or Dutch East India Companies. Dr. Utrata grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, where I received my BA in history from Stanford University with a minor in human rights. She received her MA in Conflict Transformation and Social Justice from Queen’s University Belfast as a 2017 Marshall Scholar. In her free time, she hosts and produces The Anti-Dystopians, a politics podcast about tech.

Reclaiming “The People” in an Age of Algorithms: AI Literacy as a Democratic Virtue

Hossein Dabbagh is an Assistant Professor in philosophy at Northeastern University London and an affiliate member of the Oxford Continuing Education Department. His research spans moral philosophy, applied ethics, political philosophy, and public policy, with a particular focus on AI ethics, AI-human cooperation, and democratic governance in the digital age. His recent work examines how emerging technologies shape public discourse, civic engagement, and social inequalities, emphasising the role of AI ethics education.

He advocates for integrating AI ethics into school curricula to promote critical digital literacy and responsible technology use from an early age. In addition to his academic contributions, he has provided evidence for UK government inquiries and public policy initiatives on AI regulation, misinformation, and social media governance. Beyond academia, he collaborates with interdisciplinary networks, including UNESCO’s Inclusive Policy Lab, contributing to global discussions on ethics, technology, and public policy.

Abstract: “The people” is central to democracy, reflecting ideals of collective decision-making and open debate. Yet algorithmic governance reshapes this concept by determining who participates in public discourse, amplifying some voices while silencing others. This paper argues that AI-driven polarisation calls for new approaches to civic education and engagement.

Drawing on deliberative democracy and epistemic justice, I show how algorithmic systems can weaken rational debate by prioritising viral content over verifiable facts. Social media algorithms often push emotionally charged material, fragmenting discussions and fuelling antagonism. By exploiting cognitive biases, these systems reduce “the people” to passive consumers, deepening divisions and enabling exclusionary populist narratives.

Building on Miranda Fricker’s work, I argue that AI systems can intensify testimonial and hermeneutical injustices, distorting collective meaning-making and marginalising vulnerable communities. This breakdown erodes trust and shared understanding, both essential for democracy to function. To address these issues, I propose AI ethics literacy as a core democratic virtue. Beyond technical skills, AI literacy should cultivate a critical awareness of algorithmic influences, empowering citizens to question manipulative content and preserve meaningful public debate. This interdisciplinary effort—linking philosophy, policy, and education—can help align AI governance with democratic values. Reclaiming “the people” as an active, deliberative force is both a moral and political necessity in our algorithmic era. Only by fostering a critically informed citizenry can democracy survive in a world increasingly shaped by AI.

Navigating Digital Disruptions: The Ambiguous Role of Digital Technologies, State Foundations and Gender Rights

Luana Mathias Souto is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Gender and ICT Research Group at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Spain. Principal Investigator of the project “Reproductive Health under Algorithm Surveillance (THELMA),” with a Marie Skłodowska-Curie (MSCA) Postdoctoral Fellowship by Horizon Europe. She holds a doctoral and master’s degrees in Law from Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais (PUC Minas), Brazil. During her doctoral studies, she analyzed the effectiveness of women’s political rights under Giorgio Agamben’s state of exception theory.

Her research findings also include the study of gender-political violence in Latin America. Since then, her work has analyzed the most recent threads on women’s rights, including how digital platforms increase violations of women’s rights. Her doctoral dissertation received a Magna cum Laude distinction. Her last publication is the chapter “The Biopolitical Perspective in Women’s Legal Education“ in the Routledge-edited book “Biopolitics and Structure in Legal Education.“ Formerly visiting Postdoctoral Researcher at the Max Planck Institute in Frankfurt (MPILHLT/2023) and in Hamburg (MPIPriv/2024), and Research Fellow at the Weizenbaum Institute in Berlin (2024).

Abstract: This paper explores how digital disruptions, particularly in the Rule of Law, ambiguously affect the democratic process and constrain women’s rights. In general, all the foundational elements of modern states- territory, people, and sovereignty – face significant challenges in the digital era, but the concept of people remains the most affected. Cross-border data flows, for example, challenge the principles of territoriality and sovereignty, emphasizing extraterritoriality when tech companies are based in different countries from their data users, making it difficult to protect data rights. The rise of “divisible dividual ” – individuals whose data is fragmented across various platforms – illustrates how personal data fragmentation challenges the concept of people. By examining the political, reproductive, and economic dimensions, this paper aims to shed light on the multifaceted ways digital technologies impact women’s rights. These disruptions ensure that gender inequalities remain embedded in state foundations. Even though technological advances are seen as crucial for democracy, bringing information, connecting people, and uniting diverse communities, they inherit unresolved social dilemmas, which illiberal actors explores to spread anti-gender practices in digital platforms, exacerbating the politics of “us and them ” and using gender issues as a “symbolic glue ” to weaken democracies. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing strategies to protect democratic values and promote gender equality in the digital era. This paper seeks to contribute to this ongoing conversation by providing a comprehensive analysis of the challenges and proposing potential solutions.

The Role of AI In Shaping the People: Big Tech and the Broligarchy’s Influence on Modern Democracy

Matilde Bufano is a graduate student currently finalising an MSc in International Security Studies at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies and the University of Trento. Her interests revolve around the role of AI in society in peace and war times, the exploitation of algorithms for propaganda in wartime. Her work covered the two most discussed current conflicts, namely the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas conflict.

Matilde has an interest in the right-wing extremism in peacetime, trans-exclusionary echo chambers and conspiracy theory bubbles. Theories such as QAnon and the Deep State have sparked particular interest, especially after the violent and undemocratic shifts peaked with the Capitol Hill events in the US. Matilde holds a cum laude bachelor’s degree in political science, International Relations, and Human Rights at the University of Padova.

Abstract: The main application of AI in social media is algorithmic curation based on user-preference data. Such a process creates echo chambers, i.e. bounded and enclosed media spaces in which similar content is infinitely propagated, insulating users from cross-cutting exposure. This effectively creates a distinction between “us” and “them”, grouping users in unescapable bubbles stemming from simply deduced preferences, making the gap between the two groups unbridgeable.

This has been worsened by a simultaneous reduction in fact-checking and the rise of generative AI as a disinformation creator and amplifier, with which anyone can create a video of a non-event to instigate hate and exclusion. Disinformation contains a component of exclusion, often grounded in the stark distinction between an “us” and a “them.” According to Çoksan and Yilmaz (2023), fake news can be divided into six groups: contact-outgroup blaming, represented-outgroup blaming, outgroup derogation, outgroup appreciation, ingroup glorification, and phantom-mastermind blaming.

In recent years, ingroup glorification, outgroup blaming, and derogation have become increasingly common, using minorities as scapegoats for global issues, feeding into conspiracy theories propagated by algorithmic curation like QAnon, and effectively harming democracy not only in online arenas. The rise of the (tech) broligarchy and fall of liberal democracy has been apparent in online spaces. It is now spilling over to real life, with radicalising policies online (e.g. unescapable algorithmic curation) repeating themselves in exclusionary policies in the physical world.

Panel -III-

Populist Threats to Modern Constitutional Democracies and Potential Solutions: Research Output of The Jean Monnet Chair EUCODEM

Elia Marzal is an Associate Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Barcelona. She holds a Ph.D. in Law from the European University Institute in Florence, with a dissertation on comparative constitutional law. Her research has focused on immigration, the historical development of political structures, the tensions between territorial political entities in normative production, the protection of minorities in heterogeneous states, and equality.

Theoretical Foundations of Modern Populism: Approaches of Heidegger, Laclan and Laclau

Daniel Fernández Cañueto is an Assistant Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Lleida. Director of the journal Nuevos Horizontes del Derecho Constitucional, Member of the Jean Monnet Chair EUCODEM at the University of Barcelona and junior associate researcher at the Giménez Abad Foundation. He participates in national and international research projects on institutional and democratic quality, rule of law, parliamentarism and populism. He has conducted research stays at the University of Ottawa and the University of Chile. He is also a member of the popular legislative initiatives Control Commission of the Parliament of Catalonia, a member of the Board of Advisors of the Institute for Self-Government Studies since 2021, and a member of the Board of the Association of Constitutional Lawyers of Spain. Author of several monographs and research works such as “Representación política y sistemas sociales,” (2020, CEPC), “La construcción de la representación territorial en Canadá”, (2021, Derechos Humanos, Derecho Constitucional y Derecho Internacional: sinergias contemporáneas), “Chile: de la democracia limitada de Pinochet al proceso constituyente de 2020” (2021, Revista de estudios políticos) or “Realidad constitucional, literatura y pensamiento” (2021, Revista de estudios políticos).

Abstract: Populism is widely studied in political science and constitutional law. We refer to the definition of what constitutes the current populist parties, their actions, and the consequences of their approach to political activity on democracy and constitutionalism. However, their theoretical origins have not been analyzed in depth. In my opinion, there is a connecting thread between the phenomenology of Martin Heidegger, the structuralist linguistics of Lacan, and the post-Marxist thought of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe that determines, frames, and defines the concept of populism. The aim of the paper is precisely to make this hitherto veiled connection visible, to make explicit how the critique of the universals of the Enlightenment and the fall of the Soviet Union end up having an impact on thinking about both linguistics and political theory and, from there, it is transformed into an original political thought that spreads first through Latin America and then through the rest of the West. Likewise, understanding this connection also allows us to glimpse how this populist thought is transferred, when it impacts law, into an illiberal doctrine.

Erosion of the Independence of the Judiciary

Marco Antonio Simonelli is an Assistant Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Barcelona. He obtained his Ph.D. in Comparative Constitutional Law from the University di Siena, an LL.M. in European Law from the University of Leiden, and a Law Degree from the University of Pisa. He is currently a Schumann Fellow at the University of Münster for 2025-2026 and has also completed research stays at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Public Law in Heidelberg and at the Centre of Comparative and European Constitutional Studies (CECS) of the University of Copenhagen. He was also an intern at the Rome Criminal Court of Appeal and the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe. Dr. Simonelli’s research interests focus on the multifaceted contemporary challenges to liberal constitutional democracy, with particular attention to counter-majoritarian institutions. He is the author of the book “The European Court of Human Rights and National Constitutional Courts (Springer, 2024)” and co-editor of “Populism and Contemporary Democracy: Old Problems and New Challenges” (Palgrave MacMillan, 2022), as well as several academic articles and commentaries in the field of European constitutional law published in national and international law journals.

Abstract: Since the rise of populism, the role of judges in democratic politics has become one of the major issues of debate. Populism indeed challenges one of the core tenets of constitutional liberal democracy: the idea that the judicial branch shall be separated from the legislative and the executive and that it shall be capable of controlling them. Claiming that unelected bodies cannot override the will of elected ones, populist leaders indeed attempt to depict the judges as “enemies of the people”. Recent developments in both established and emerging democracies—including open challenges to the validity of judicial decisions and questioning the impartiality of courts—demonstrate that no democracy is immune to these pressures. At the same time, the growing polarization of the political arena reverberates also on judicial appointments, further treating the independence of the judiciary and its ability to uphold legal and constitutional principles. Against this backdrop, this paper examines the impact of populism on judicial independence by providing a comparative review of the most common strategies employed by populist governments to undermine judicial independence, such as court-packing, changes in the appointment system, the conferral of disciplinary powers in the Minister of Justice as well the public delegitimization of courts. In parallel, the paper, drawing on national experiences, also explores the most effective strategies for insulating ordinary and constitutional courts from political branches, thereby contributing to the strengthening of constitutional democracy in an era of rising illiberalism.

Referenda as a Biased and Populist Tool: Addressing a Complex Issue in a Binary Way

Elia Marzal Yetano is an Associate Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Barcelona and until 2022 she was professor of Constitutional Law and Legal History at ESADE Law School, Ramon Llull University, Barcelona. She holds a Ph.D. in Law from the European University Institute in Florence, with a dissertation on comparative constitutional law, in which she analyzed the convergence of legislative and jurisdictional entities in the creation of law in the specific field of immigration. Other than on immigration, her research has focused on the historical development of political structures, the tensions between territorial political entities in normative production, the intersection between Constitutional law and history, the protection of minorities in heterogeneous states, and issues on equality. Her research has been published in national and international journals, including the European Journal of Political Research, Managerial Law, Revista de Derecho Político, Revista Crítica de Derecho Inmobiliario, Revista de Estudios Políticos, Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español, Revue Historique de Droit Français et Étranger or the International Journal of Constitutional Law.

Abstract: For secessionist movements, Canada and the United Kingdom represent examples of overcoming the traditional reluctance of liberal democracies to consider holding secession referendums as a means of resolving territorial conflicts. However, the doctrine established by the Supreme Court of Canada (later echoed in the United Kingdom) does not place the referendum at its core; rather, Parliament holds a prominent position. This paper examines the actual role assigned to Parliament within that doctrine and its potential implications for the framework of constitutional democracy. It analyzes the reasoning found in the key texts that support this doctrine—namely, the 1998 opinion of the Supreme Court of Canada on Quebec’s secession, the 2000 federal Clarity Act, and the 2022 opinion of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom on Scotland’s ability to unilaterally call a new secession referendum—assessing the weight given to Parliament from a social choice perspective. Two main conclusions emerge. First, the doctrine acknowledges the relationship between the legitimacy of a decision and the costs inherent in the decision-making process, which increase as the decision becomes more divisive within the affected community. Second, it implicitly highlights the need to nuance and complicate the liberal democratic fiction of a singular people and a general will, suggesting that in certain contexts, majority-rule democracy should be complemented by consensus democracy.

Pro-independence Movements as a Populist Way Out

Núria González Campañá is an Assistant Professor in Constitutional Law at the University of Barcelona. She received her DPhil in Law from the University of Oxford in 2019. Prior to that, she obtained her M.A. in Law and Diplomacy (The Fletcher School, Tufts University) and her B.A. in Law (University of Barcelona). Her main research interests are: 1) Self-determination and secession in Spanish, comparative and EU constitutional law and 2) Populism, constitutional democracy and rule of law. Among her research, the monograph “Secession and European Union Law. The deferential attitude” (Oxford University Press) was nominated for the 2024 Book of the Year prize awarded by the International Forum on the Future of Constitutionalism. In addition to being a team member in national research projects, she has also been a member of the European project “Democratic Efficacy and the varieties of populism in Europe”, led by Prof. Boda Zsolt, Institute for Legal Studies (Budapest) and funded by the European Commission. She is currently a member of the “core team” of the Jean Monnet Chair in European Constitutional Democracy (EUCODEM) at the University of Barcelona. She has carried out research stays at McGill University and the European University Institute.

Abstract: Spain is not alien to the phenomenon of populist narratives and constitutional erosion. Although probably unnoticed by international audiences, one of the most relevant examples of constitutional erosion that has taken place in Spain in recent years was the Catalan secessionist bid. In this paper, I’ll focus on one populist trait of the pro-independence movement: the illiberal interpretation of democracy. Catalan pro-independence leaders made great efforts to build the case that organizing a referendum on secession is a question of democratic quality. “Voting is normal in a normal country” or “This is about democracy” were some of the most repeated slogans. However, only a few democracies (e.g. Canada and the UK) have permitted a vote on the secession of a part of the country. Other constitutional democracies (e.g., the US, Italy, and Germany) have rejected the idea that one part of the country can organize a referendum on secession.

Catalan pro-independence leaders assumed that democracy, understood as majority rule, should trump any other legal principle, like the rule of law, respect for minorities, or federalism. But democracy is not only about voting or about the wishes of the majority. Constitutional democracy means people decide but do so according to rules that can only be changed following their amendment procedure. However, in the populist narrative of the Catalan pro-independence movement, a majoritarian concept of democratic legitimacy took prevalence over the rule of law, and the popular will was conceived as the only source of power. The implication was that ‘the people’ cannot be wrong, and therefore, leaders and parliaments should find a way to carry out people’s aspirations, regardless of the letter of the law. The referendum became a moral goal, the only tool to allow for the political expression of the people’s will. Oriol Junqueras, former Vice-President of the Catalan government, insisted several times that “voting is a right that prevails over any law” This opposition between purported popular legitimacy and legality implies an illiberal version of democracy. The idea of the government of the people is taken literally, and checks and balances on the popular will are rejected.

Potential Solutions: Second Chambers, Demos and Majoritarian Body

Roger Boada Queralt is an Assistant Professor of Constitutional Law at ESADE Law School in Barcelona. He has also been a Visiting Professor at the Centre for Transnational Legal Studies at King’s College London. He received his PhD from ESADE Law School and his LLM from Duke University School of Law. He has devoted much of his research to the constitutional theory developed by the School of Salamanca, particularly that of Francisco de Vitoria and Francisco Suárez. His book The Limits on State Power in the Thought of Francisco de Vitoria and Francisco Suárez has been published in Spanish by the Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. In addition, he has written a chapter devoted to counterpowers in the School of Salamanca for a collective work titled Counterpowers in Constitutional Democracy in the Face of the Populist Threat, coordinated by Josep Maria Castellà and Enriqueta Expósito and published in Spanish by Marcial Pons. He has also lectured on the relevance of the notion of common good in contemporary Constitutional Law and its connections with the School of Salamanca. His current research focuses on second chambers in Spanish and Comparative Constitutional Law, with a particular focus on the Senate of Spain as a moderating chamber in the context of an imperfect bicameral system, as well as on the ongoing and potential reforms of the House of Lords.

Abstract: Second chambers in bicameral legislatures have long been debated in constitutional design. Nowadays, they often oscillate between two broad roles, which are not necessarily mutually incompatible. The first one would be that of a territorial chamber, which provides a channel for the participation of regions and federated states in the decision-making process at the national level or that specialises in issues related to regional autonomy or the territorial organisation of power. The second one would be that of a moderating chamber with varying degrees of political power, whose raison d’être would be to provide a check on the lower chamber, improve the quality of legislation, provide for more sober reflection, and pursue a broader consensus on disputed issues. Drawing on the distinction between these two models and adopting a Comparative Constitutional Law perspective, this presentation shall explore their potential as institutions capable of reflecting more complex demos while acting as moderators against the unchecked impulses of purely majoritarian bodies. The presentation will focus on the Senate of Spain and the British House of Lords, with particular emphasis on their role as moderating chambers in a context of imperfect bicameralism, which places them in a position of relative weakness vis-à-vis their respective lower chambers. The analysis will be enriched by relevant political developments and potential constitutional reforms. By integrating lessons from both countries, it shall posit that, even in an imperfect bicameral system, second chambers can enhance deliberation, restraint and stability, countering the risks of populist or unreflective majoritarianism.

Panel -IV-

Politics of Belonging: Voices and Silencing

Azize Sargin is an independent researcher and consultant of external relations for non-governmental organisations. She holds a doctorate in International Relations, with a focus on Migration Studies, from the Brussels School of International Studies at the University of Kent. Her research interest covers migrant belonging and integration, diversity and cities, and transnationalism. Azize had a 15-year professional career as a diplomat in the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where she held various positions and was posted to different countries, including Romania, the United States, and Belgium. During her last posting, she served as the political counsellor at the Permanent Delegation of Turkey to the EU.

Anne-Margret Wolf is a Fellow at All Souls College, University of Oxford, where she researches authoritarian politics, focusing on the Middle East and North Africa. She has a particular interest in Tunisia, a country where she has researched for over a decade. Dr. Wolf is the author of Ben Ali’s Tunisia: Power and Contention in an Authoritarian Regime (Oxford University Press, 2023) and Political Islam in Tunisia: The History of Ennahda (Oxford University Press, 2017). She is also the Editor of The Oxford Handbook of Authoritarian Politics.

The Scents of Belonging: Olfactory Narratives and the Dynamics of Democratization

Maarja Merivoo-Parro is a historian dedicated to exploring the history of mentality at the intersection of culture and politics in democratization processes. A Fulbright scholar, she is currently a Marie Curie Fellow at the University of Jyväskylä, where she examines the role of grassroots international relations in shaping civic identities. Her interdisciplinary research combines political history, sensory studies, and oral history to uncover how cultural experiences influence democratic engagement. Beyond academia, Maarja is an active young public intellectual who has recently gained national recognition for her work in bridging scholarly research and society. She has brought complex historical and political topics to wider audiences through television and radio programs, making history accessible and relevant to contemporary debates. She has been a longtime board member of the Baltic Heritage Network and the Estonian Diaspora Academy, contributing to international efforts to document and analyze migration, memory, and transnational cultural connections. Having conducted extensive oral history research across multiple continents, she is committed to preserving lived experiences as vital sources of historical knowledge. She has been awarded with the AABS Emerging Scholar Grant for continuing her contributions to the field.

Abstract: Amid the global erosion of democracies, cultural and sensory dimensions play an often-overlooked role in shaping collective identities and fostering civic cohesion. My research investigates how olfactory heritage – embedded in shared memories, rituals, and environments – historically contributed to defining “the people” in democratic and undemocratic contexts. This paper explores how olfactory cues have served to strengthen the democratic process and, conversely, to fuel divisions.

Through case studies from Finland and (Soviet-)Estonia, I analyze the interplay between olfactory culture and the rhetoric of “us” versus “them.” For instance, how have national and local scents – such as those tied to cross-border communication, industrial heritage, family celebrations, or contested spaces – shaped everyday understandings of democracy?

By combining sensory history with political theory, this study highlights the potential of olfactory heritage to serve as a medium for democratization and social cohesion, offering a novel perspective on the dynamics of civic identity.

This presentation employs an interdisciplinary approach, integrating sensory history, olfactory cultural studies, and political theory. Using archival sources, oral histories, and the media, I trace how olfactory practices have been used to define boundaries of inclusion and exclusion within democratic and authoritarian regimes. The study further explores how olfactory narratives interact with other cultural markers, such as music, art, and public ceremonies, in shaping aspirational and actual civic identities in the long 20th century.

Transnational Solidarity Movements: Autogestion, Community Building and Defining Colonial Alterity between French Algeria and Israel/Palestine

Sara Elizabeth Green is a DPhil candidate in History at the University of Oxford. Her research examines transnational solidarity movements with the Palestinian cause in the wake of decolonisation, particularly how thinking about Palestinian displacement and dispossession reflects and shapes historical memory of settler colonialism; concepts of indigeneity and belonging; gender and affect in anticolonial politics; cultural decolonisation in the era of ‘Third World’ internationalism. She previously completed her undergraduate studies in History at the University of Leeds, followed by the MSt in Global and Imperial History at the University of Oxford, where her thesis focused on the racialised representations of female nudity and modesty in French colonial ethnography of Algeria (1881-1931).

Abstract: This paper will explore cultures of autogestion and democratic community building by Jewish and Muslim actors in Palestinian solidarity movements after the decolonisation of French Algeria (1964-1974). In a context of calculated state restrictions on the political and associative activities of stateless political exiles and immigrant communities, these spaces provided an avenue to discuss and define the parameters of colonial privilege and alterity between French Algeria and Israel/Palestine. Between clandestine networking with anticolonial militants across continents, or the circulation of cassette tapes connecting the Palestinian struggle with racial policing in postcolonial France in factories and worker’s unions, this paper will explore the methods used by activists to foster Muslim-Jewish dialogue under a state apparatus that frequently presumed the perpetual enmity of these communities. In particular, the development of a connected culture of memorialisation of colonial violence connected the displacement of Palestinian ‘undesirables’ to the waves of racially motivated violence and political assassinations that targeted these communities over the course of the 1970s. This reconfigured the notion of ‘the people’ by recentring the humanity of Palestinian, Arab and Jewish victims of racialisation and undermining the separatist logic that defined inequality in Israel/Palestine, particularly beyond the confines of official French perspectives that continued to characterise and surveille militants of the Algerian ‘rebellion’, Muslim and Jewish alike, as ‘subversive’ agents.

Silent Symbols, Loud Legacies: The Child in Populist Narratives of Post-Communist Poland

Maria Jerzyk is a Polish sociology student at Masaryk University in Brno, Czechia. Her research spans populism studies, childhood studies, and the sociology of food, but at its core, it asks one fundamental question: how does the past quietly dictate the present? Viewing social realities through a post-Soviet trauma lens, she investigates how historical experiences of repression and transformation leave echoes in contemporary political rhetoric, cultural anxieties, and even what we eat. She is particularly fascinated by how populist movements weaponize the idea of childhood—simultaneously portraying children as symbols of purity and obedience while excluding those who challenge traditional norms. Beyond politics, she explores how food practices reflect national identity, historical trauma, and power dynamics. Through her interdisciplinary approach, she seeks to uncover the hidden ways inherited fears and unspoken histories continue to shape modern life. By blending political analysis with cultural sociology, her work offers a fresh perspective on how the ghosts of the past find their way into today’s populist narratives and everyday rituals.

Abstract: This paper explores the ambivalent role of children in populist discourse, focusing on Poland’s right-wing populist government (2015–2023) under Law and Justice (PiS). Populist rhetoric constructs childhood through a paradox: children are simultaneously portrayed as obedient, passive figures in need of protection and as “bad” or “dangerous” when they exhibit independence, agency or engage in activism. This dichotomy is further intensified when children’s perceived transgressions align with broader populist social divisions, such as identification with LGBTQ+ communities or participation in wide-variety movements, leading to their symbolic exclusion from the national collective.

The study analyzes political speeches from Law and Justice politicians, illustrating how these narratives frame childhood as a battleground for moral and ideological struggles. Additionally, it situates these discursive strategies within Poland’s post-communist context, where Soviet-era ideals of disciplined and collectivist youth continue to resonate with populist audiences. By examining propaganda films from Polska Kronika Filmowa, the paper traces continuities between communist and populist constructions of childhood, demonstrating how historical narratives are reactivated to legitimize contemporary exclusionary politics. Through this analysis, the paper highlights how the figure of the child becomes a potent symbol in populist storytelling, shaping political identities and reinforcing cultural anxieties in post-communist Poland.

Panel -V-

Governing the ‘People’: Divided Nations

Leyla Aliyeva is an Associate of REES, Oxford School for Global and Area Studies (OSGA), previously Senior Common Room Member and Academic Visitor at St. Antony’s College, Oxford University. She holds a PhD from Moscow University. Originally from Azerbaijan, she founded and directed two think tanks in Baku and held fellowships at Harvard University, UC Berkeley, the Kennan Institute (Washington, DC), the NATO Defence College (Rome), and the IFK (Institut Für Kulturwissenschaften) in Vienna. My research and publications cover Azerbaijan, the Caucasus, Russia, and the broader Former Soviet Union, and range thematically from energy security and conflicts to democracy in oil-rich states, as well as issues surrounding integration into the EU (ENP and EaP) and NATO. Currently, Leyla is analysing the role of religious identities in transition, as well as comparing the role of the opposition in rentier states.

Karen Horn is Professor in Economic Thought, University of Erfurt.

Catholicism and Nationalism in Croatia: The Use and Misuse of “Hrvatski Narod”

Natalie Schwabl is a doctoral candidate at the Faculty of Arts, Languages, Literature and Humanities of Sorbonne University/Paris, under the supervision of Professor Johann Chapoutot. The subject of her thesis is “Violence and Religion in the ‘Independent State of Croatia’ (1941-1945)”, focusing on the role of the Catholic clergy under the Croatian Ustasha regime. She is of German and Croatian origin and grew up and began her studies in Germany after a German-French Bachelor of Arts in History and French (Literature, Linguistics and Translation) at the universities of Mainz (Germany), Dijon (France) and Sherbrooke (Canada), she obtained her Master’s degree in Modern History at Sorbonne University in 2022, where she has been a Junior Lecturer in History since 2021, for classes in Modern History and English.

Abstract: This paper explores the relation between the Croatian state and radical Catholicism, including the role of the Catholic church as an institution, throughout the 20th century, until today. The inextricable link between Catholicism and nationalism in Croatia was fostered by the frequent change of regimes in the 20th century: the “First Yugoslavia” under the Karađorđević dynasty (1918-1929, 1929-1941), the “Independent State of Croatia” (1941-1945) and the fascist Ustasha regime, the “Second Yugoslavia” under Tito who died in 1980 and, after 1991, the new Republic of Croatia. As the most important vector of national identity for the Croatian people and the projection of their feeling of belonging to the West, the Catholic Church was omnipresent in Croatian political, social and cultural life.