Please cite as:

ECPS Staff. (2025). “ECPS Conference 2025 / Roundtable I — Politics of the ‘People’ in Global Europe.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). July 8, 2025. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00103

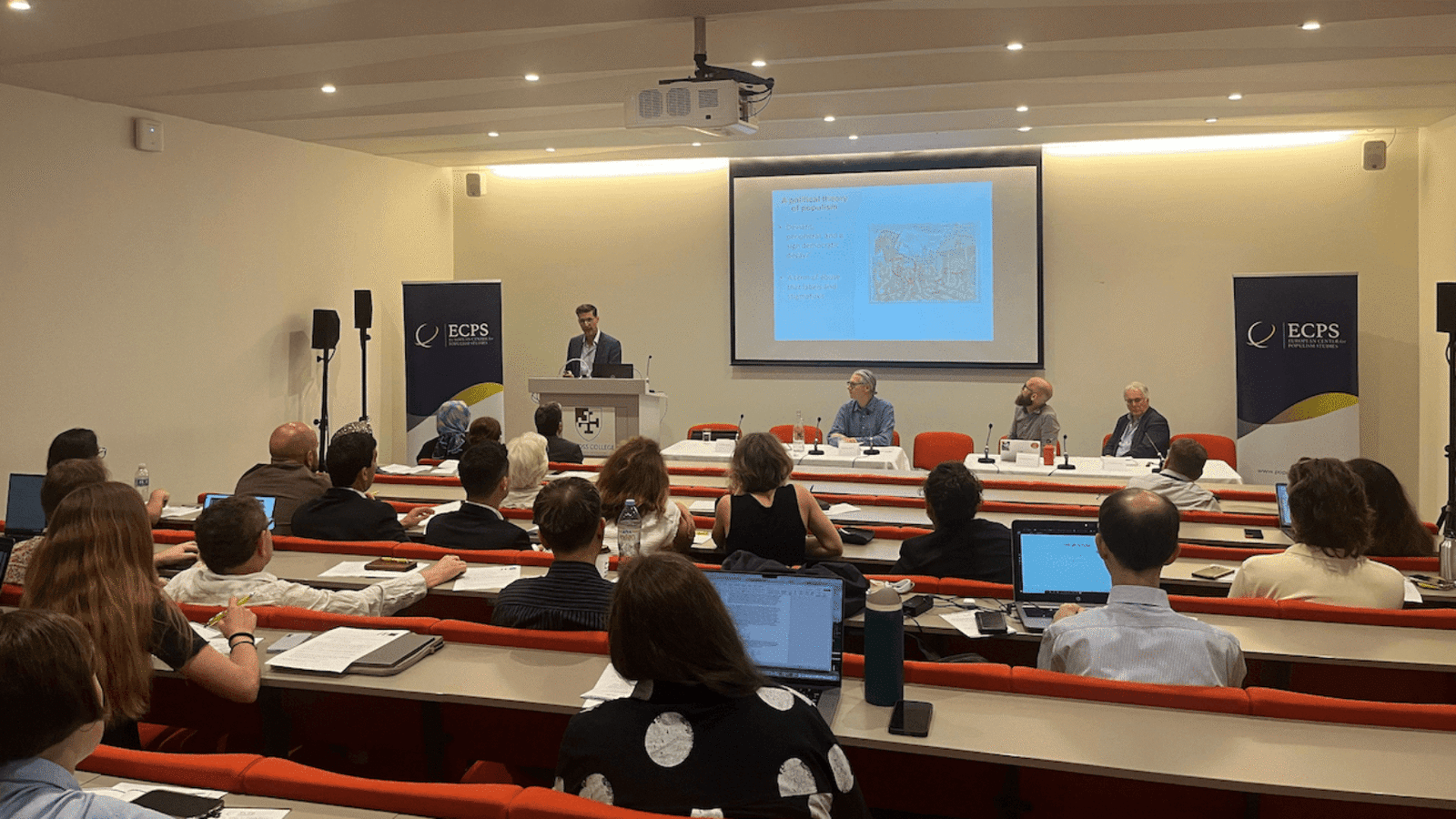

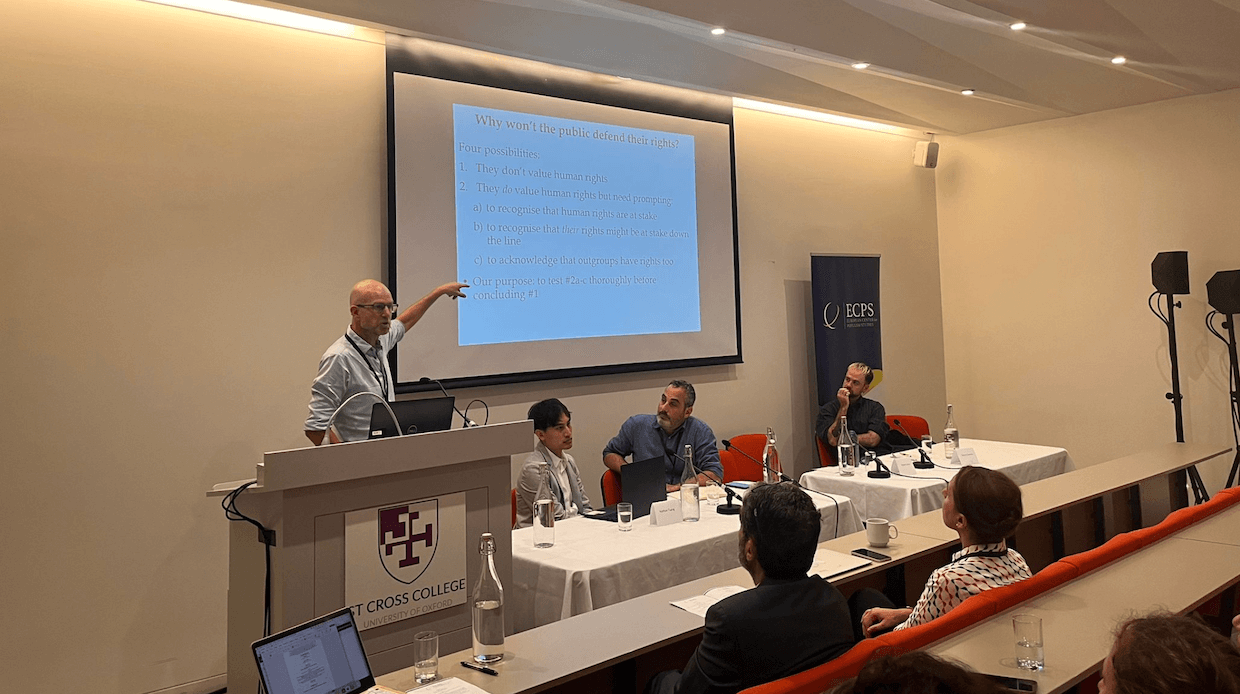

Held at the University of Oxford on July 1, 2025, Roundtable I of the ECPS Conference launched the discussions of “‘We, the People’ and the Future of Democracy.” Chaired by Professor Jonathan Wolff, the session explored how “the people” is constructed, contested, and deployed in contemporary European and global politics. Presentations by Professors Martin Conway, Aurelien Mondon, and Luke Bretherton examined the historical resurgence of popular politics, the elite-driven narrative of the “reactionary people,” and the theological dimensions of populism. Together, the contributions offered a nuanced, interdisciplinary account of how populism’s democratic and anti-democratic potentials shape the political imagination and institutional realities of the 21st century.

Reported by ECPS Staff

Roundtable I of the ECPS Conference, hosted at the University of Oxford on July 1-3, 2025, brought together leading scholars to explore the shifting meanings and political uses of “the people” in contemporary Europe and beyond. Titled “Politics of the ‘People’ in Global Europe,” this session opened the in-person component of the Conference “‘We, the People’ and the Future of Democracy,” an interdisciplinary initiative addressing the democratic backsliding, populist resurgence, and the pathways toward civic resilience in the 21st century.

Chaired by Professor Jonathan Wolff (Senior Research Fellow, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford; President, Royal Institute of Philosophy), the roundtable featured three distinguished speakers: Professor Martin Conway (University of Oxford), Professor Aurelien Mondon (University of Bath), and Professor Luke Bretherton (University of Oxford). Their presentations tackled the historical re-emergence of “the people” as a political category, the elite construction of the so-called reactionary public, and the theological undercurrents of populist discourse—particularly in relation to Christianity.

Taken together, the presentations demonstrated that “the people” is not a static or universally democratic force. Rather, it is a flexible and contested category, often constructed, instrumentalized, and redefined by elites, political movements, and media systems. While it can serve as a source of democratic renewal—as in historical instances of resistance to authoritarian regimes—it can also be mobilized to undermine pluralism, dismantle institutions, and sacralize exclusionary forms of nationalism.

The roundtable emphasized that populism is neither inherently democratic nor inherently authoritarian. Its normative direction depends on how “the people” are imagined, who is included or excluded, and whether political participation is broadened or curtailed. The session challenged participants to move beyond reductive narratives that blame “the people” for democratic erosion, instead urging deeper inquiry into how elites, ideologies, and media infrastructures shape public discourse and democratic practice.

As Europe and its transatlantic partners grapple with polarized electorates, declining trust in institutions, and re-enchanted political imaginaries, understanding the politics of “the people” remains central to safeguarding and reimagining democratic life in our time.

Professor Martin Conway: “The Reappearance of ‘The People’ in European Politics”

In his compelling presentation, Martin Conway, Professor of Contemporary European History, University of Oxford, explored the reemergence and reconfiguration of “the people”in contemporary European politics. He framed his remarks within a broader intellectual and historical reflection on democratic transformation and political disruption, noting that current anxieties about populism echo earlier eras of upheaval in European history.

Professor Conway began by acknowledging what he termed a prevailing “liberal anxiety”—a sense of unease about the future of democracy that has come to define our political moment. This anxiety, articulated by many mainstream figures including Baroness Royall and commentators like Timothy Garton Ash, reflects a broader fear that democracy is moving in a precarious or even regressive direction. Conway noted that this sentiment contrasts sharply with the optimism of two decades ago, when history was assumed to be progressing in a linear, liberal-democratic trajectory. The shift, he argued, is not unprecedented; similar concerns were widespread in Europe on the eve of the revolutions of 1848. Today, we once again live in a period marked by ambient pessimism and apprehension about what lies ahead.

Several structural transformations underpin this shift, according to Professor Conway. First, he pointed to the stagnation and decline of living standards across much of Europe. While there are exceptions—such as regions in Spain or Poland—many Europeans have experienced over a decade of economic insecurity, eroding the sense of progress and stability that once undergirded liberal democratic institutions. This economic fragility, exacerbated by global market forces and the retreat of the welfare state, has deeply unsettled large segments of society, particularly small businesses, farmers, and precarious workers.

A second, related transformation is the collapse of analog political structures and their replacement by digital media environments. Professor Conway emphasized that the move to digital communication has “anarchized” political debate by weakening the traditional channels—such as party structures and deliberative institutions—that previously organized and moderated political participation. What has emerged in their place is a more fragmented, volatile, and emotionally charged political space.

Beyond these socio-economic and technological shifts, Professor Conway focused on a deeper historical development: the breakdown of a stable model of disciplined, representative democracy that had defined much of postwar Europe. This model, characterized by proportional representation, enduring party systems, and a deeply embedded political elite, ensured predictability and continuity. Politicians might lose a seat in parliament, but often resurfaced in other public roles—“never losing the chauffeur-driven car,” as Professor Conway wryly observed, referencing Belgian politics.

Today, according to Conway, that model is under strain. Challenger parties—often short-lived, leader-centric, and ideologically fluid—have emerged across Europe. They range from the Flemish nationalist Vlaams Belang to leftist, Maoist-rooted movements in Belgium and populist coalitions in Italy. These parties often lack coherent platforms but are united in their appeal to “the people” as a reactive force. Their rise reflects the erosion of elite control and the democratization—but also destabilization—of political life.

Populism, Professor Conway argued, is the label most often applied to this phenomenon. However, he warned that historians are justifiably skeptical of the term. While political scientists like Cas Mudde have successfully theorized populism as a “thin ideology,” historians are more attuned to national contexts, ideological distinctions, and historical specificity. The danger, Conway suggested, lies in collapsing all anti-establishment movements into a single, undifferentiated category, thereby overlooking the distinct traditions—secular, religious, leftist, rightist—that shape each movement.

Nonetheless, Professor Conway underscores that populism, for all its analytical imprecision, captures a genuine insurgent reality: the reassertion of “the people” in forms that diverge significantly from the norms of 20th-century political action. These new forms of engagement are often marked by a rejection of institutional decorum, a distrust of expertise, and the rise of emotionally driven, male-dominated political performances that are less about coherent goals and more about expressive, affective protest.

This shift from rational deliberation to emotional expression—what Professor Conway termed “a change in the musical key of European politics”—is both a cultural and political transformation. It reflects not only structural changes in how politics is conducted, but also the symbolic and psychological reorientation of “the people” as a force both feared and romanticized. Whereas 1989 symbolized the disciplined, hopeful advance of freedom through mass protest in Eastern Europe, today’s mobilizations often appear to many observers as erratic, exclusionary, and disruptive.

Professor Conway underscored that the liberal political class has responded by building rhetorical and institutional defenses—what he called “anti-popular politics.” These include efforts to create legal buffers against referenda, avoid direct electoral challenges, and portray populist movements as inherently irrational, racist, or manipulated by shadowy online forces. Yet such reactions, he warned, risk becoming elitist and anti-democratic in themselves.

In his closing reflections, Professor Conway posed several critical questions: Why did we assume that history would progress smoothly and democratically? Why do we dismiss the democratic potential embedded in disruptive and turbulent popular movements? And crucially, why are we so unwilling to recognize that today’s “people,” for all their volatility, remain committed to democratic participation—albeit in forms unfamiliar and uncomfortable to the liberal imagination?

The reappearance of “the people” in European politics, Professor Conway concluded, should not be seen merely as a threat. Rather, it presents an opportunity—if approached critically and constructively—to rethink the boundaries, forms, and aspirations of democracy in 21st-century Europe.

Professor Aurelien Mondon: “The Construction of the Reactionary People”

In his incisive presentation, “The Construction of the Reactionary People,” Aurelien Mondon, Professor of Politics, University of Bath, critically unpacked the prevailing narrative that positions contemporary far-right and authoritarian populism as an authentic expression of the will of “the people.” Drawing on over 15 years of research, Professor Mondon challenged the assumption that the so-called “reactionary people” are an organic democratic force. Instead, he argued that this concept is largely an elite-driven construction—a top-down narrative shaped by media, political actors, and intellectuals.

Professor Mondon began by distinguishing between two problematic “P” words: populism and the people. He cautioned against the overuse and imprecision of populism as a catch-all term, which, he argued, has distracted scholars and commentators from a more meaningful analysis of democracy. Instead, he emphasized the importance of critically interrogating how the people are represented, invoked, and constructed in political discourse—especially in reactionary and exclusionary ways.

Central to Professor Mondon’s argument is the idea that the figure of the reactionary people—often depicted as the “white working class” or “the left behind”—has been strategically constructed by elite discourse to justify regressive political shifts. Citing the rhetoric of Nigel Farage and Donald Trump, Mondon highlighted how these elite actors positioned themselves as champions of ordinary people, despite their wealth and elite status. For example, in a speech delivered shortly after the Brexit vote and just before Trump’s election in 2016, Farage drew a direct connection between disaffected Welsh voters and the American rust belt, constructing a transatlantic narrative of popular revolt. Yet, as Professor Mondon pointed out, this framing was less about listening to real grievances and more about legitimizing reactionary, often xenophobic agendas under the guise of popular will.

Empirically, Professor Mondon’s research—particularly in collaboration with Dr. Aaron Winter—demonstrates that the supposed mass support of the white working class for Brexit and Trump has been overstated or misrepresented. Their studies of electoral data reveal that lower-income individuals were in fact less likely to support Trump or Brexit. Many abstained from voting altogether, and among those who did vote, a significant proportion supported establishment candidates such as Hillary Clinton or remained skeptical of nationalist populism. Trump’s and Brexit’s bases, according to the presentation of Professor Mondon, were more accurately characterized by middle- and upper-income voters, including older property owners—groups not typically considered “left behind” in any meaningful socioeconomic sense.

Yet this data was widely ignored in mainstream discourse. Prestigious media outlets—from Newsweek and The Guardian to The Washington Post and Harvard Business Review—repeatedly promoted the notion that the rise of Trump and Brexit reflected the voice of the working-class majority. Professor Mondon emphasized that political scientists, journalists, and commentators across the spectrum helped entrench this myth. In doing so, they lent legitimacy to exclusionary and reactionary politics, even while claiming to merely reflect public sentiment.

Importantly, Professor Mondon warned that this elite narrative has real consequences. It racializes the working class by equating working-class identity with whiteness, thereby excluding ethnic minorities and immigrants who are themselves often working-class. It naturalizes racism by framing it as an inevitable response to economic hardship, rather than a political choice or a construct of political elites. And it normalizes regressive politics by presenting them as the authentic voice of a democratic majority.

This construction is, to Professor Mondon, continually reinforced by media coverage. For example, recent violent anti-migrant demonstrations in the UK were portrayed by outlets like the BBC as expressions of legitimate, working-class anger—despite the racist and xenophobic nature of the acts. The BBC even apologized for calling the far-right Reform Party “far-right.” Similarly, headlines after these riots claimed they were driven by “economic grievances,” offering justification rather than critique.

Professor Mondon challenged this narrative with data from Eurobarometer surveys, which show a stark gap between what people say matters to them personally—such as healthcare, jobs, and education—and what they perceive as problems for the country—typically immigration, a perception shaped by media and political discourse. During the 2016 Brexit campaign, for example, immigration emerged as a top concern at the national level, but it barely registered as a personal priority. This discrepancy reveals the power of media agenda-setting and elite framing in constructing “public opinion.”

Professor Mondon further questioned why only certain actors are granted the status of “the people.” Those protesting for climate action, racial justice, or trans rights are often dismissed as “elite,” “woke,” or “naïve.” Meanwhile, racist protestors, anti-migrant agitators, or conservative culture warriors are hailed as representing “real people” with “legitimate concerns.” Even billionaire authors like J.K. Rowling, or politicians like Farage and Trump, are cast as victims of elite suppression and defenders of democratic expression.

This discursive bias shapes policy outcomes. Both conservative and center-left parties—such as Labour under Keir Starmer—justify rightward shifts in immigration and cultural policy by claiming they are responding to “the people’s” demands. Yet, Professor Mondon argued, such moves are often preemptive responses to media-generated moral panics rather than genuine democratic pressures. The result is a cycle in which reactionary politics are platformed and amplified, while progressive movements are marginalized.

In concluding, Professor Mondon offered several urgent recommendations. First, we must stop exaggerating the electoral strength of the far right and critically interrogate low voter turnout and political disengagement. Second, we should resist euphemizing reactionary politics as “populism”—if a policy is racist or authoritarian, it should be named as such. Third, we must reject the reflex to blame “the people” for the democratic crisis, and instead scrutinize how power, media, and elite discourse mediate public knowledge and shape perceptions. Finally, Professor Mondon called for a critical reassessment of liberalism’s role in enabling far-right resurgence. Liberal elites’ failure to address inequality, racism, and disenfranchisement has contributed to the very crisis they now lament.

Rather than discarding “the people” as a dangerous force, Professor Mondon argued, scholars and policymakers must engage more honestly with the democratic potential of the broader population. The challenge lies not in taming the people, but in confronting the forces that construct reactionary myths in their name.

Professor Luke Bretherton: “Christianity in A Time of Populism”

In his presentation, Luke Bretherton, Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford, offered a nuanced theological and political analysis of populism, with particular attention to its relationship with Christianity. Rather than treating populism solely as a pathological deviation from democratic norms—as is common in much of the European and North American literature— Professor Bretherton argued that populism is a perennial and ideologically fluid component of democratic life. Populism, he suggested, oscillates between democratic and anti-democratic forms, each shaping the political terrain in profound, and at times, conflicting ways.

Professor Bretherton opened by critiquing the dominant academic and journalistic lens through which populism is often viewed—namely, as an aberration associated with far-right, anti-immigrant movements. This narrow interpretation, he argued, overlooks historical and global instances of populism as vehicles of democratization, such as the Solidarity movement in Poland, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, and even populist peasant movements like La Vía Campesina. He emphasized that populism’s ideological indeterminacy makes it resistant to clear categorization on the traditional left-right spectrum, functioning instead as a vessel for diverse, often contradictory, political projects.

According to Professor Bretherton, populism’s complexity lies in its dual potential: it can either renew democratic life or corrode it. Drawing on the work of Margaret Canovan and Ernesto Laclau, Bretherton explained that populism arises from tensions internal to democracy itself, particularly between its redemptive promise—rule by the people—and its pragmatic reality, in which elite negotiation and institutional mediation often dominate. When the redemptive aspect is perceived to have been lost, populist movements emerge to reclaim it, often invoking the language of purity, moral renewal, and direct representation.

To differentiate forms of populism, Professor Bretherton proposed a typology contrasting democratic populism with anti-democratic populism. Democratic populism seeks to broaden political participation, construct shared moral vocabularies, and nurture long-term, deliberative engagement. It builds institutions, invests in civic education, and aims to create pluralistic forms of common life. Examples include community organizing movements like Citizens UK or the early American Populist movement of the late 19th century, which drew on religious traditions to foster democratic deliberation.

By contrast, anti-democratic populism, according to Professor Bretherton, simplifies political space through exclusion and dichotomy, often bypassing deliberative institutions in favor of plebiscitary rule and strongman leadership. It construes the people in essentialist, ethnoreligious, or racialized terms, delegitimizing opposition as traitorous or unpatriotic. Leaders like Donald Trump embody this form of populism, claiming to represent the “real people” while delegitimizing institutional checks and balances.

Professor Bretherton warned that while both forms of populism share characteristics—emphasis on leadership, romanticization of the “ordinary people,” skepticism toward elites and bureaucracy—they differ in their normative trajectories. Democratic populism aims to cultivate shared responsibility for the common good, while anti-democratic populism facilitates personal withdrawal from public life and the erosion of civic institutions in favor of authoritarian consolidation.

The latter part of Professor Bretherton’s presentation focused on the intersection between populism and Christianity. He argued that populism draws heavily on theological tropes, often reconfiguring religious narratives to legitimize its political vision. Christian theology itself, according to him, has longstanding populist impulses—particularly within Protestant traditions that emphasize unmediated access to God and critique ecclesial hierarchy. These impulses have historically fueled resistance to both clerical and political elites. However, Professor Bretherton cautioned that such impulses can be co-opted by anti-democratic populist movements, as seen in the rhetoric of far-right parties like Germany’s AfD or France’s Rassemblement National, which claim to defend Christian culture while attacking institutional churches.

Professor Bretherton emphasizes that this tension stems from the anti-institutional nature of anti-democratic populism, which bypasses mediating structures—such as churches or representative institutions—in favor of a direct identification between the leader and the people. Theologically, this dynamic manifests as a form of idolatry, in which the nation or a charismatic leader is elevated to a messianic role, effectively substituting for Christ. Bretherton described this as a “Christophobic and anti-ecclesial” form of Christianity—one that empties faith of its creedal and ethical commitments and repurposes it as a tool of exclusionary cultural identity.

Rather than treating Christian references in populist rhetoric as merely superficial or secularized, Professor Bretherton argued that we are witnessing a re-enchantment of political discourse. Far-right populism, he contended, does not secularize Christian symbols but sacralizes secular notions like sovereignty and nationhood, effectively reversing the modern trajectory of disenchantment. This shift represents a new kind of political theology, one in which secular concepts are infused with religious meaning, producing an existential, quasi-spiritual political struggle.

Professor Bretherton highlights global examples—from Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Islamist turn in Turkey to the rise of Hindu nationalism in India—that illustrate the resurgence of political movements in which the sacred and the political are strategically recombined with potent effect. In Europe, this re-enchantment emerges in response to technocratic liberalism’s perceived hollowness and its failure to address existential anxieties, community dislocation, and crises of agency.

Professor Bretherton concluded by asserting that Christianity must confront these dynamics with a return to its core commitments: love of God and neighbor, solidarity with the stranger, and the rejection of idolatrous narratives of salvation through nation or leader. The Church, he insisted, must become a site of resistance against both authoritarianism and technocratic alienation by cultivating forms of common life grounded in justice, plurality, and mutual care. The ultimate theological task, he contended, is to convert politics from a false gospel of domination into a means of neighboring—turning the earthly city into a penultimate place of peace rather than seeking salvation through it.

Conclusion

Roundtable I of the ECPS Conference 2025 at the University of Oxford offered a compelling and multifaceted reflection on the politics of “the people” in a time of democratic uncertainty and populist resurgence. Under the skillful moderation of Professor Jonathan Wolff, the session foregrounded how “the people” remains a highly malleable and contested category—evoked to both revitalize and erode democratic life. Drawing on historical, political, and theological perspectives, the speakers dismantled simplistic narratives that equate populism either with democratic renewal or authoritarian decline. Instead, they highlighted the need to interrogate how elites, institutions, and media infrastructures construct and instrumentalize notions of “popular will” for divergent ends.

A shared theme emerged: that contemporary politics is marked not simply by polarization, but by a crisis of representation, legitimacy, and moral imagination. Whether in the reappearance of emotionally charged political forms (Conway), the elite-driven construction of reactionary publics (Mondon), or the sacralization of exclusionary ideologies (Bretherton), the roundtable underscored the urgency of rethinking democratic participation. As the idea of “the people” continues to shape our political futures, this conversation reminded us that its meaning must remain a site of critical, ethical, and democratic contestation.

Note: To experience the panel’s dynamic and thought-provoking Q&A session, we encourage you to watch the full video recording above.