ECPS convened Session 10 of its Virtual Workshop Series, bringing together scholars to examine how democracies endure, adapt, and contest authoritarian pressures amid the normalization of populist discourse and the weakening of liberal-constitutional safeguards. Chaired by Dr. Amedeo Varriale, the session framed resilience as an active democratic project—defending rule of law, pluralism, and civic participation against gradual forms of authoritarian hollowing-out. Presentations by Dr. Peter Rogers, Dr. Pierre Camus, Dr. Soheila Shahriari, and Ecem Nazlı Üçok explored resilience across market democracies, local governance, feminist self-administration in Rojava, and diaspora activism confronting anti-gender politics. Discussants Dr. Gwenaëlle Bauvois and Dr. Gabriel Bayarri Toscano connected these contributions through probing questions on the ambivalence, burdens, and transformative potential of resilience.

Reported by ECPS Staff

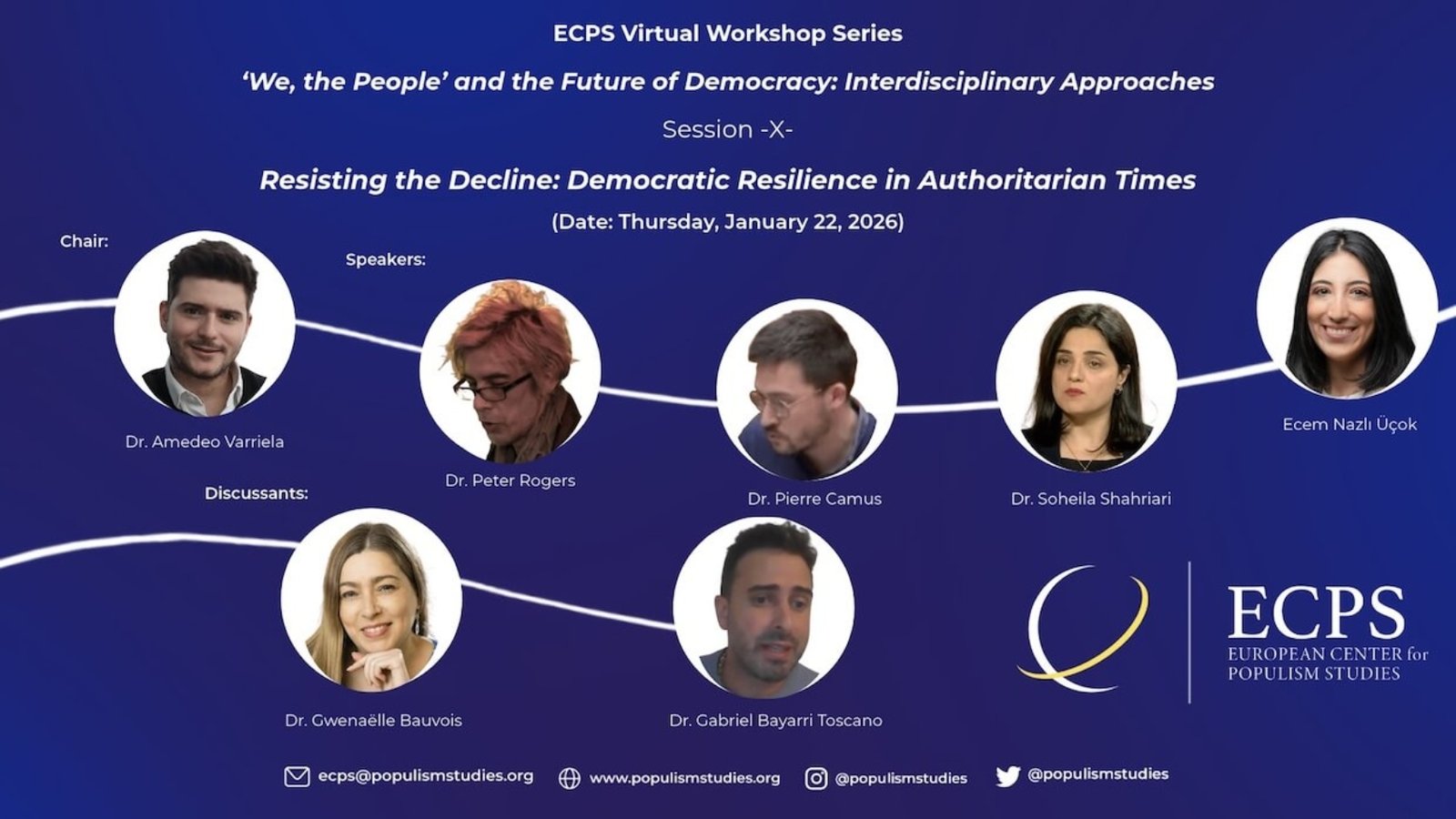

On Thursday, January 22, 2026, the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS) convened Session 10 of its Virtual Workshop Series, titled “We, the People” and the Future of Democracy: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Held under the theme “Resisting the Decline: Democratic Resilience in Authoritarian Times,” the session brought together an interdisciplinary group of scholars to examine how democratic systems, institutions, and civic actors seek to withstand—and, at times, transform—the pressures generated by authoritarian resurgence, the normalization of populist discourse, and the erosion of liberal-constitutional guarantees across diverse political contexts.

The workshop opened with welcoming remarks by ECPS’s Reka Koleszar, who introduced the session’s theme, outlined the format, and presented the contributing scholars and discussants. Her opening situated Session 10 within ECPS’s broader intellectual agenda: advancing comparative, theory-informed, and empirically grounded research on populism and its implications for democratic governance, civic space, and rights-based politics.

The session was chaired by Dr. Amedeo Varriale (PhD, University of East London), whose framing remarks offered a synthetic lens for the panel. Drawing attention to the contemporary “populist zeitgeist,” Dr. Varriale underscored how authoritarianism increasingly advances not merely through abrupt ruptures, but through gradual practices that hollow out democratic norms while preserving formal institutional shells. Against this backdrop, he proposed democratic resilience as an active project: the defense of rule of law, pluralism, and rights through institutions and civic participation, as well as the re-engagement of citizens whose disillusionment can become a resource for anti-democratic entrepreneurs.

Four presentations explored resilience across distinct but connected domains. Dr. Peter Rogers (Senior Lecturer in Sociology, Macquarie University) delivered “Resilience in Market Democracy,” interrogating resilience as a traveling concept shaped by market logics, welfare-state capacities, and shifting moral expectations of citizenship. Dr. Pierre Camus (Postdoctoral Fellow, Nantes University) presented “The Contradictory Challenges of Training Local Elected Officials for the Future of Democracy,” analyzing how professionalization and training—often justified as democratizing—can also reproduce inequalities and widen the distance between representatives and citizens. Turning to conflict and non-state governance, Dr. Soheila Shahriari (EHESS) offered “The Rise of Women-Led Radical Democracy in Rojava,”examining feminist self-administration as civil-society resilience amid regional authoritarianism and geopolitical exclusion. Finally, Ecem Nazlı Üçok (PhD Candidate, Charles University) presented “Feminist Diaspora Activism from Poland and Turkey,” conceptualizing exile-based feminist organizing as a site of transnational resistance to anti-gender politics and authoritarian repression.

Discussion was enriched by two discussants: Dr. Gwenaëlle Bauvois (University of Helsinki) and Dr. Gabriel Bayarri Toscano (Rey Juan Carlos University), whose interventions connected the papers through shared questions about the ambivalence of resilience, the distribution of democratic burdens, and the conditions under which resilience becomes transformative rather than merely adaptive.