Please cite as:

Ivaldi, Gilles & Zankina, Emilia. (2024). “Conclusion.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism.(eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0087

DOWNLOAD CONCLUSION

The reconfiguration of the extreme right in the European Parliament reaffirms prior tendencies and analysis (i.e., that despite the increased representation of radical-right actors, they continue to be divided and unable to act as a united front). Hence, we can expect more ad hoc coalitions on specific issues rather than united positions and policy proposals. What should not be neglected, although, is the legitimation of the radical-right discourse and its impact on both European and domestic politics.

By Gilles Ivaldi* Sciences Po Paris–CNRS (CEVIPOF), France & Emilia Zankina** Temple University, Rome, Italy

This report has examined the electoral performances of populist parties in the 2024 European elections. The collection of country chapters provides a unique source of information to understand the electoral dynamics of populist parties across Europe, highlighting similarities and differences in the economic, social and political context of the European elections in the 27 EU member states. Here, we summarize the main findings from the individual chapters and provide some general conclusions.

The diversity of the European populist scene

The individual country chapters illustrate the diversity of populism in Europe and the variety of its manifestations across the political spectrum. The findings in this report corroborate the vast literature on populism, which has long identified the plurality of articulations between the ‘thin’ ideology of populism and the ‘thicker’ host ideologies to which it attaches itself. As suggested in the individual chapters, in Western Europe, populism is essentially found to the left and right of the spectrum, while in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), we see a more diverse array of populist actors.

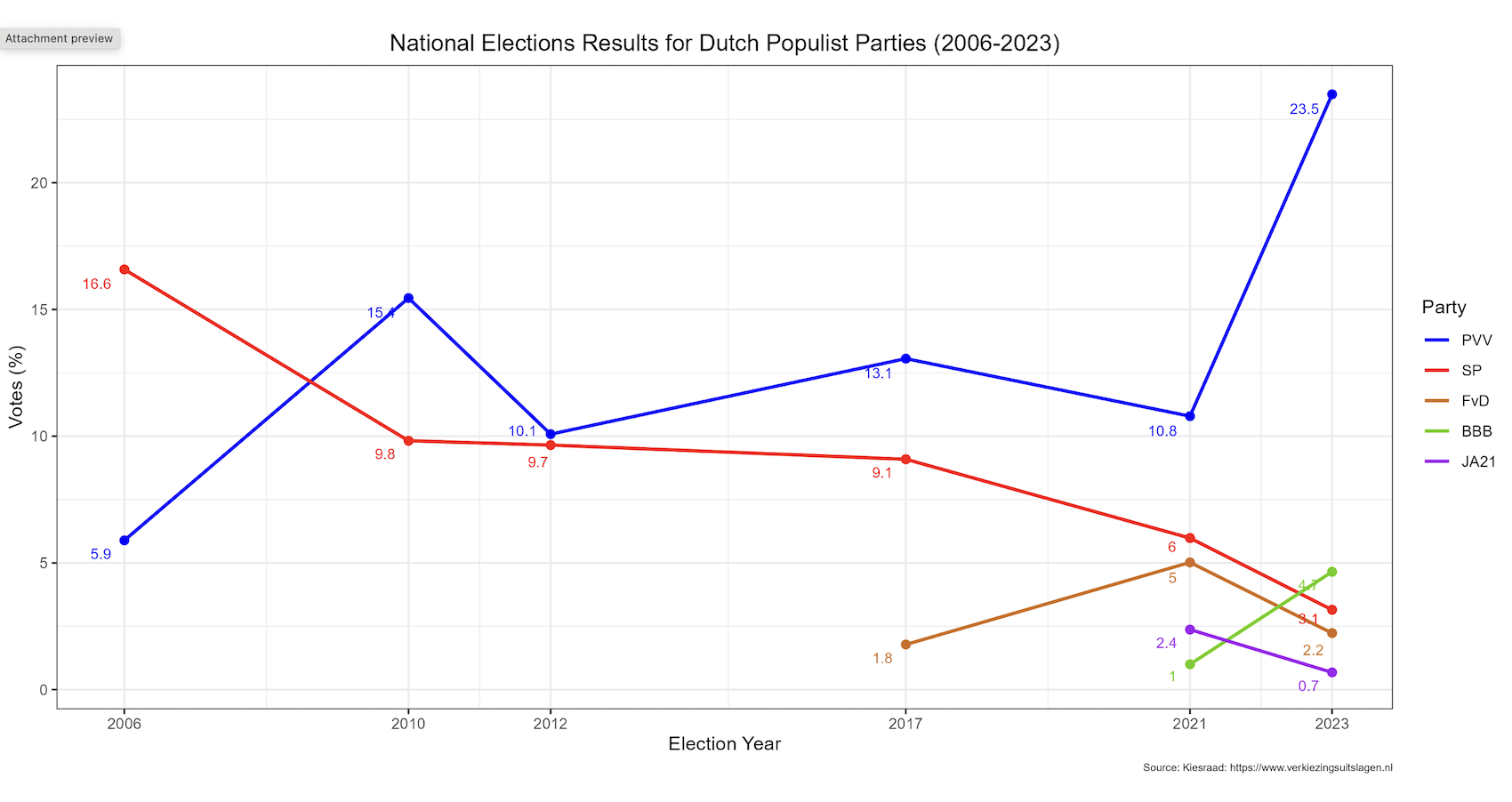

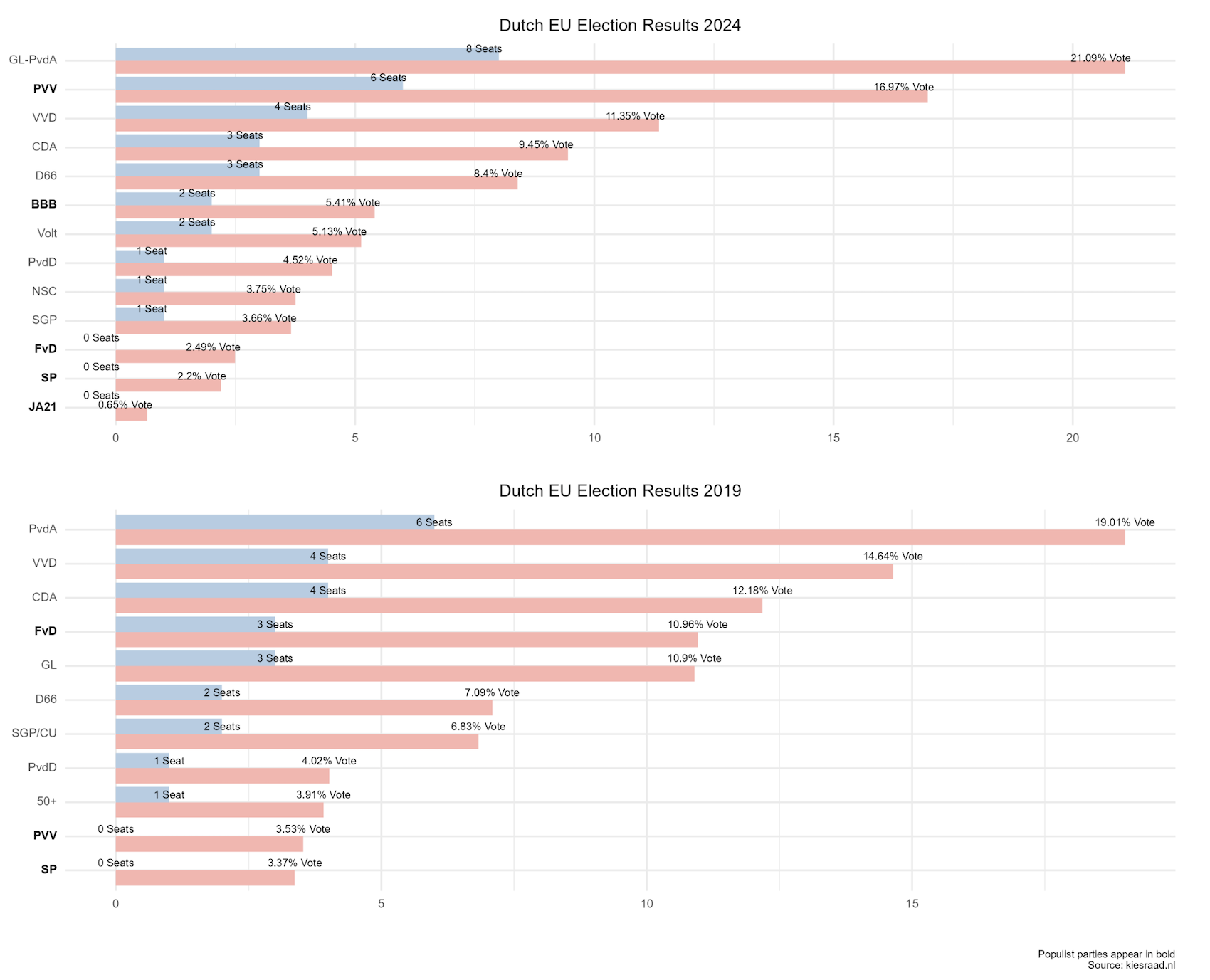

Some individual countries provide a good illustration of such diversity. The Netherlands has long been a breeding ground for populism. Over the years, there has been a succession of populist parties, ranging from right-wing nativist and left-wing populist to agrarian populist. Similarly, Spain has experienced both left and right-wing populism with Podemos and Vox. In Belgium, there are two cases of populist radical parties to the left (PTB–PVDA) and right (VB) of the ideological spectrum. Italy has been described as nothing less than a ‘populist paradise’, hosting a wide range of populist parties. Such diversity is also found in countries like France and, more recently, Germany, with the rise of the BSW to the left of the party spectrum. While in Greece, left–populist parties have been dominant with Syriza and KKE, the populist radical right has long been present with parties such as Golden Dawn and, most recently, with EL and the Democratic Patriotic Movement or ‘Niki’.

There is even more diversity when looking at the populist scene in Central and Eastern Europe. Populists in the centre dominated the elections in Bulgaria, with GERB gaining over 24% of the vote, and in the Czech Republic, with ANO securing 26%. The centrist Prodalzhavame promyanata (PP) and ITN in Bulgaria also registered strong results, with 14% and 6% of the vote, respectively. In Slovakia, it was the left populists of SMER who carried the day, securing 25% of all votes cast. The radical right fared well in all three countries, with Vazrazhdane gaining over 14% in Bulgaria, Hnutie Republika attracting 13% in Slovakia, and Přísaha a Motoristé registering over 10% of the vote in the Czech Republic.

Diversity is also found in the interpretation of populism by populist parties. While populism is still seen as a core feature of the populist right across most cases, there seems to have been a shift away from populist narratives and themes in some parties of the populist left, such as Podemos in Spain, the SP in the Netherlands, and the SF in Denmark. In Spain, for instance, there has been a decline in the use of populist ideas by Podemos, which has turned more clearly to radical-left ones. Moreover, there seems to be less consensus about the populist nature of radical-left parties, as illustrated by Die Linke in Germany, the Left Wing Alliance (VAS) in Finland, the Left Party in Sweden, and the Left Bloc (BE) in Portugal, which may also signal a move away from populism towards a more classic radical-left agenda. The Bulgarian GERB has also significantly moved away from populist narratives, focusing primarily on pro-EU rhetoric. While the Romanian AUR remains Eurosceptic, it has been focusing on specific issues rather than on criticizing the European project itself.

Together with their different locations on the party spectrum, populist parties also diverge in their issue positions. As the country chapters show, this is particularly true of the populist right where substantial differences are found, for instance, in terms of those parties’ economic policies.

In a context marked by rising prices and the inflation crisis, right-wing populist parties have adopted a wide array of economic positions, reflecting diverging economic strategies and the adaptation by populist parties to different contextual opportunities. In France, for example, the RN has significantly moved to the economic left, advocating redistributive policies. In Denmark, the DF combines welfare-chauvinist positions with a good portion of nostalgia. In the Netherlands, the PVV takes a protectionist and welfare-chauvinist position aimed at voters with lower incomes who are most hit by high energy prices. In Cyprus, ELAM supports left-wing economic policies aimed at wealth redistribution and increased state intervention in market regulation. In Estonia, EKRE focuses on economic welfare and regional disparities, as does the EL in Greece, although it combines welfare chauvinism and government interventions with calls for low taxation. Welfare chauvinism and socialist nostalgia have been the trademarks of radical-right populist parties in Bulgaria, but they have also been explored by left populists such as SMER in Slovakia.

In contrast, other right-wing populist parties are found on the economic right. The Dutch FvD, for instance, is more free-market-oriented than the PVV and most other populist radical-right parties in Europe. In Finland, the Finns Party has recently turned to the right on the economy. In Luxembourg, the Alternativ Demokratesch Reformpartei (ADR) exhibits a national-conservative profile and generally maintains a distrust of big government. In Greece, Niki is more free market and low taxation than EL. In Romania, AUR has increasingly introduced neoconservative elements.

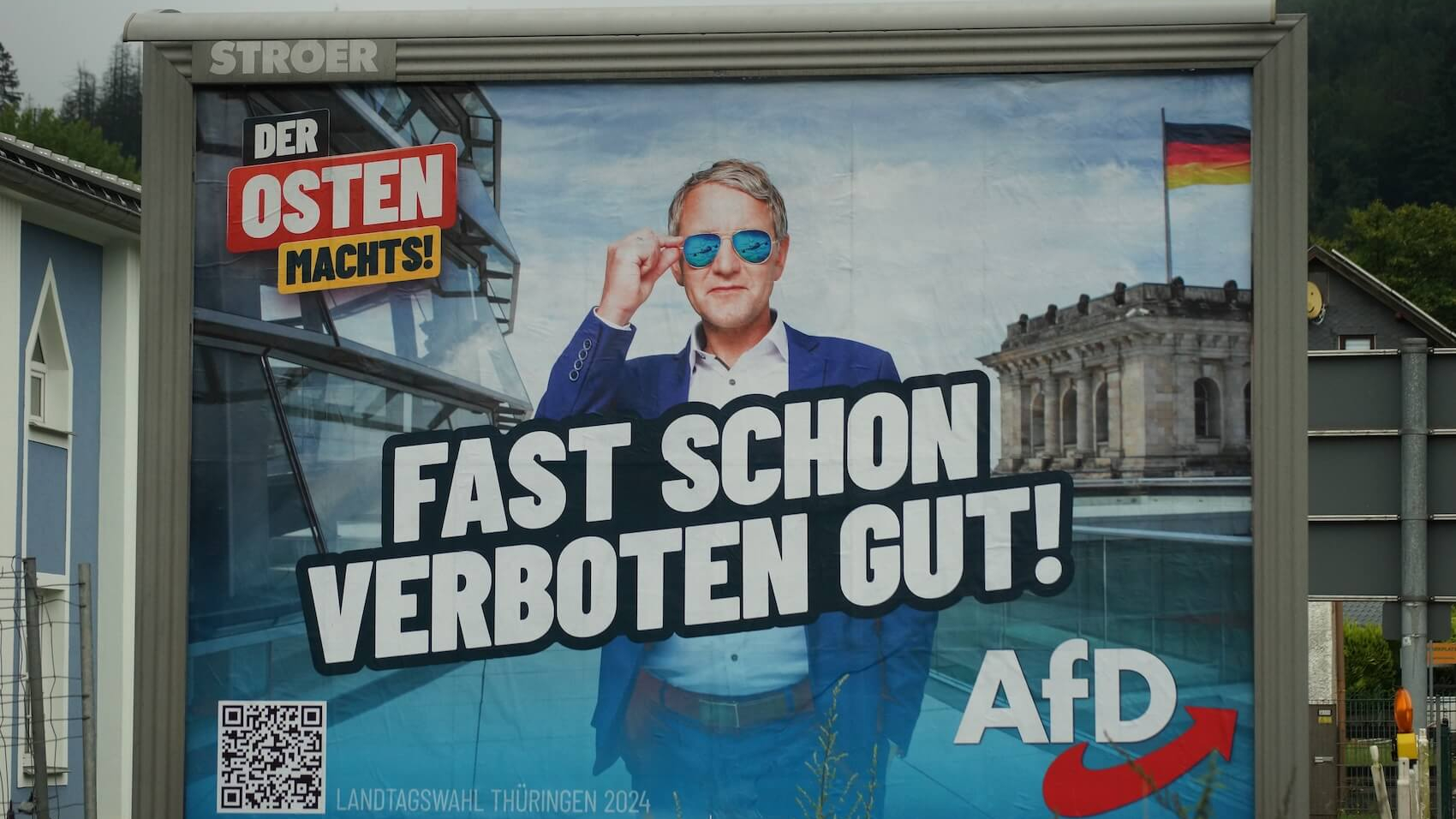

Finally, the analysis in this report shows that populist parties differ widely with regard to their political status within their respective political systems. Parties such as the French RN and German Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) are still political pariahs. In Germany, the AfD remains deeply unpopular, and the party has faced strong criticism for its many controversial statements and positions regarding immigration, Islam and the Second World War. In France, despite Marine Le Pen’s de-demonization strategy, the persistence of the RN’s profile as a political pariah was exposed in the 2024 legislative elections where the traditional Republican Front – that is, ad hoc alliances of parties or voters (or both) across the spectrum whenever the RN is likely to win a decisive round – was revitalized. In contrast, Mélenchon’s populist left LFI has managed to establish itself as a coalition partner to the rest of the left. Another case of a cordon sanitaire around the populist radical right is that of Belgium, where leaders of the N-VA continue to close the door to the Vlaams Belang. In Central and Eastern Europe, extreme parties such as Revival in Bulgaria, AUR in Romania or Hnutie Republika in Slovakia are still kept outside mainstream politics despite growing electoral support.

Elsewhere, however, the current trend is one of increasing mainstreaming and normalization of populist parties as a result of a dual process of modernization and moderation by populists, on the one hand, and accommodation of populist ideas and policies by mainstream parties, on the other hand. Such dual process has been well documented in the recent populism literature (Akkerman, de Lange, and Rooduijn, 2016; Herman and Muldoon, 2019; Mondon and Winter, 2020; Mudde, 2019) and the country chapters in this report corroborate both the centripetal move by a number of populist parties from the margins to the centre of national politics and the accommodation of populism by mainstream actors.

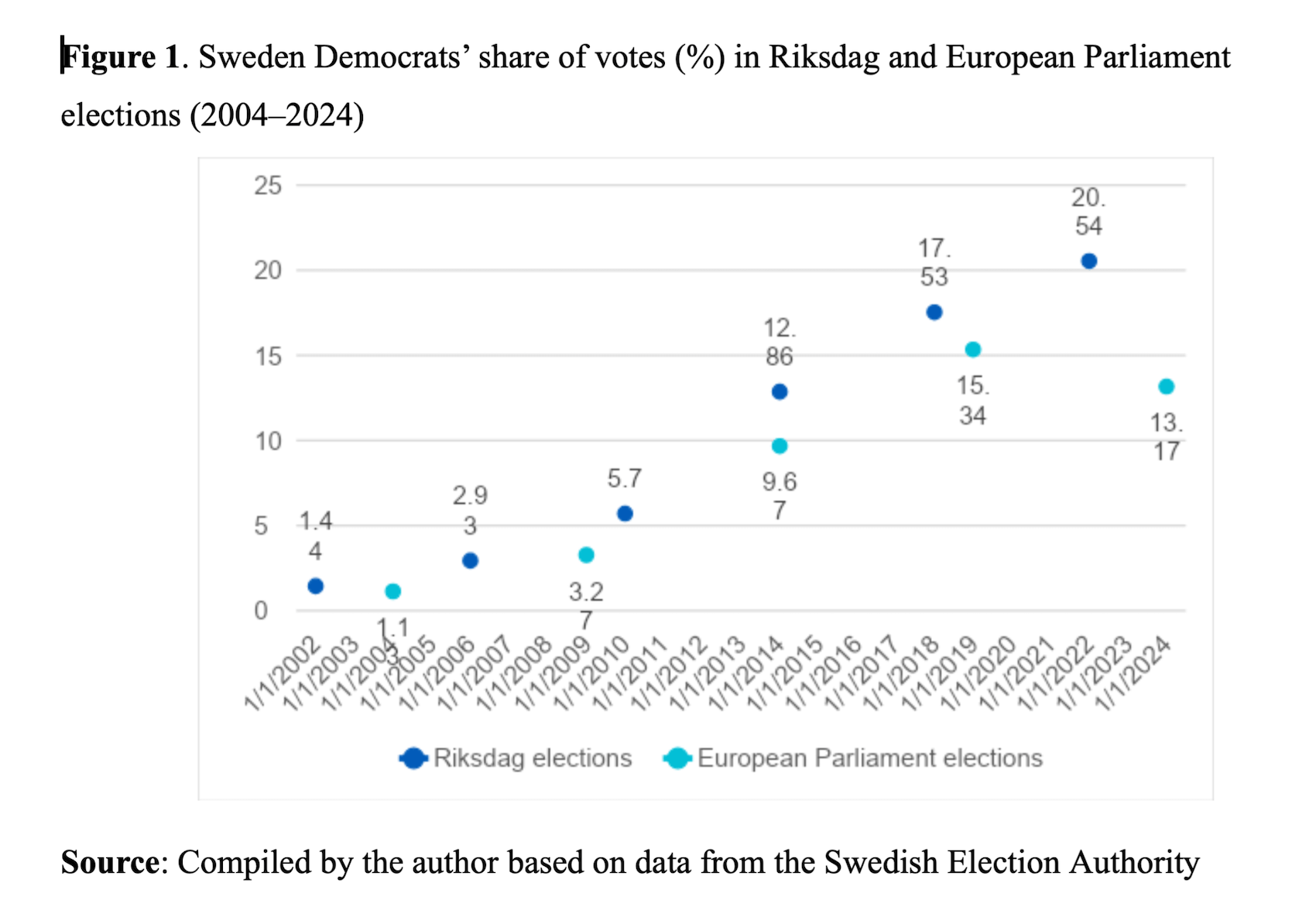

Populist accommodation by parties of the mainstream is traditionally found in countries such as Italy and Austria. In CEE, such cooperation has been found in Poland, Slovakia and Bulgaria during the 2017–2019 government. This has more recently been the case, for instance, in the Netherlands, where the change in VVD party leadership has produced a change of strategy towards the PVV, with the new VVD party leader Dilan Yeşilgöz openly suggesting that her party would no longer exclude a government with Wilders. In Sweden, the cordon sanitaire was breached before the 2022 parliamentary election when three of the centre-right parties expressed a more open stance towards the Sweden Democrats. In Cyprus, despite its radical positions and extreme right-wing roots, ELAM has managed to integrate into the political mainstream, collaborating with other parties on specific issues in the House of Representatives since 2016.

Populists against Europe? The strategic moderation of populist Euroscepticism

The modernization of populist politics concerns, in particular, the moderation and blurring of those parties’ positions regarding European integration. The country chapters illustrate such a dampening of Eurosceptic politics, both left and right of the populist spectrum. In many cases, the analysis shows that populist parties have recently abandoned their previous hard Eurosceptic plans to exit the Euro or the EU, often adopting ambiguous positions vis-à-vis European integration and a softer tone vis-à-vis the EU. As discussed in the introduction of this report, this represents a strategic move by populists to increase their appeal to moderate and pro-EU voters and to foster collaboration with mainstream parties.

In France, the RN has abandoned its previous policy of “Frexit”, while de-emphasizing European issues to increase its appeal to moderate voters. Like the RN, LFI has toned down its Euroscepticism in recent years, moving away from its previous call to leave the EU and that France should disobey the European treaties. In Sweden, the SD have moderated their Euroscepticism and dropped their demand for a referendum on EU withdrawal. Such a move has also been visible in the Netherlands, where Wilders has successfully presented himself as a more moderate candidate, no longer calling for a Nexit but promising to reform the EU from within. In Portugal, Chega has articulated some soft Euroscepticism in its European election manifesto. In Italy, Fratelli d’Italia advocates for national sovereignty over supranational integration while maintaining a relatively moderate stance on opposition to the European Union. A similar dampening of Eurosceptic policies and themes has been found in the Lega and M5S since 2018. In Finland, the Finns Party has abandoned its long-term goal of withdrawing from the EU. A stronger support for the EU is found in Luxembourg, where the ADR explicitly acknowledges the great advances the EU had given to Europe in terms of peace and prosperity in post-war Europe while praising the positive benefits the EU and immigration have brought to the country. In Greece, the left-populist Syriza put forward a version of soft Euroscepticism, criticizing the EU’s democratic deficit. The right-wing populist EL has been advocating for a Europe made of nation-states, but it has not been openly calling for Grexit, and neither has the other new right-wing populist party, Niki. The FPÖ clearly stated that it would not aim for an ‘Öxit’, although it called for cuts in the EU budget and institutions and a Union based on subsidiarity and federalism.

In Western Europe, the German AfD stands out for its hard Eurosceptic positions. The most radical faction has dominated the AfD since 2017. In the run-up to the 2024 European elections, the party initially called for the dissolution of the European Union in its manifesto but dropped this demand from the final manifesto after facing public backlash. The Dutch FvD similarly favours Nexit. In Greece, the communist KKE has similarly maintained a hard Eurosceptic stance (as well as an anti-NATO stance), supporting Greece’s exit from the EU and accusing it of being imperialistic, anti-democratic, capitalist and exploitative.

Populists in Central and Eastern Europe widely vary in their level of Euroscepticism. The Croatian right-populist DL, for example, exhibits a soft Eurosceptic orientation, framing the EU as a confederation of sovereign states and never advocating for closer relations with ‘alternative partners’ in global politics, such as Russia, China or the BRICS. The DL expresses a strong opinion against further EU enlargement due to Serbia’s candidacy status, while the Romanian AUR, on the contrary, advocates for EU memberships for Moldova. By contrast, the Bulgarian Vazrazhdane urges for an immediate exit from NATO and the EU, while centrist populist parties in Bulgaria, such as GERB and PP, are ardently pro-European. Czech populists from the centre and the right expressed different levels of criticism towards the EU. ANO, which has been in opposition since 2021, gradually shifted from a mildly pro-European stance towards soft Euroscepticism. The SPD, on the other hand, has sustained its uncompromisingly anti-immigration and hard Eurosceptic rhetoric, describing the EU as a ‘dictatorship in Brussels’ dominated by ‘non-elected bureaucrats’ who produce ‘directives that are against the interests of our state and our people’. Euroscepticism is extremely limited in Estonia, where 77–78% of the population supports EU membership.

Similarly, in Latvia, voters tend to support sober, politically experienced personalities to represent Latvia’s national (rather than party) interests in the European Parliament, leaving little room for Eurosceptic rhetoric. In Romania, AUR has softened its Euroscepticism, while the new SOS prides itself in being the first to advocate for a ‘Ro-exit’. In Slovakia, the ruling SMER claims to support EU membership despite its many shortcomings, while ĽSNS argues that the EU cannot be reformed. Consequently, its party leader promised to ‘lay the groundwork for Slovakia’s exit from the European Union and break the EU from within.’

Populist parties, particularly of the radical right, have been shying away from hard Eurosceptic positions, emphasizing an intergovernmental vision of a community of sovereign and independent states, now claiming to reform the EU ‘from within’ while opposing further enlargement of the EU. As the country chapters in this report show, right-wing populist parties across Europe continue to vilify a ‘bureaucratic EU’. ‘Taking back control’ from Brussels has become a common theme of right-wing populist narratives. In Belgium, the VB has been using the ‘taking back control’ tagline while denouncing EU leaders as ‘extremists’, bureaucrats and technocrats. In the Netherlands, the PVV’s European electoral program emphasized the need to reform the EU from within rather than to leave the Union. In Italy, while cooperating with the EU, Giorgia Meloni’s FdI continues to engage in ideological struggles on specific policies such as civil liberties, environmental issues, gender equality and EU constitutional matters. The Danish DF claims the EU needs to be strongly downsized to safeguard national sovereignty, a similar claim to that of the Denmark Democrats, which ask for ‘less EU’ and more national sovereignty.

Were the 2024 EP elections another ‘populist’ moment?

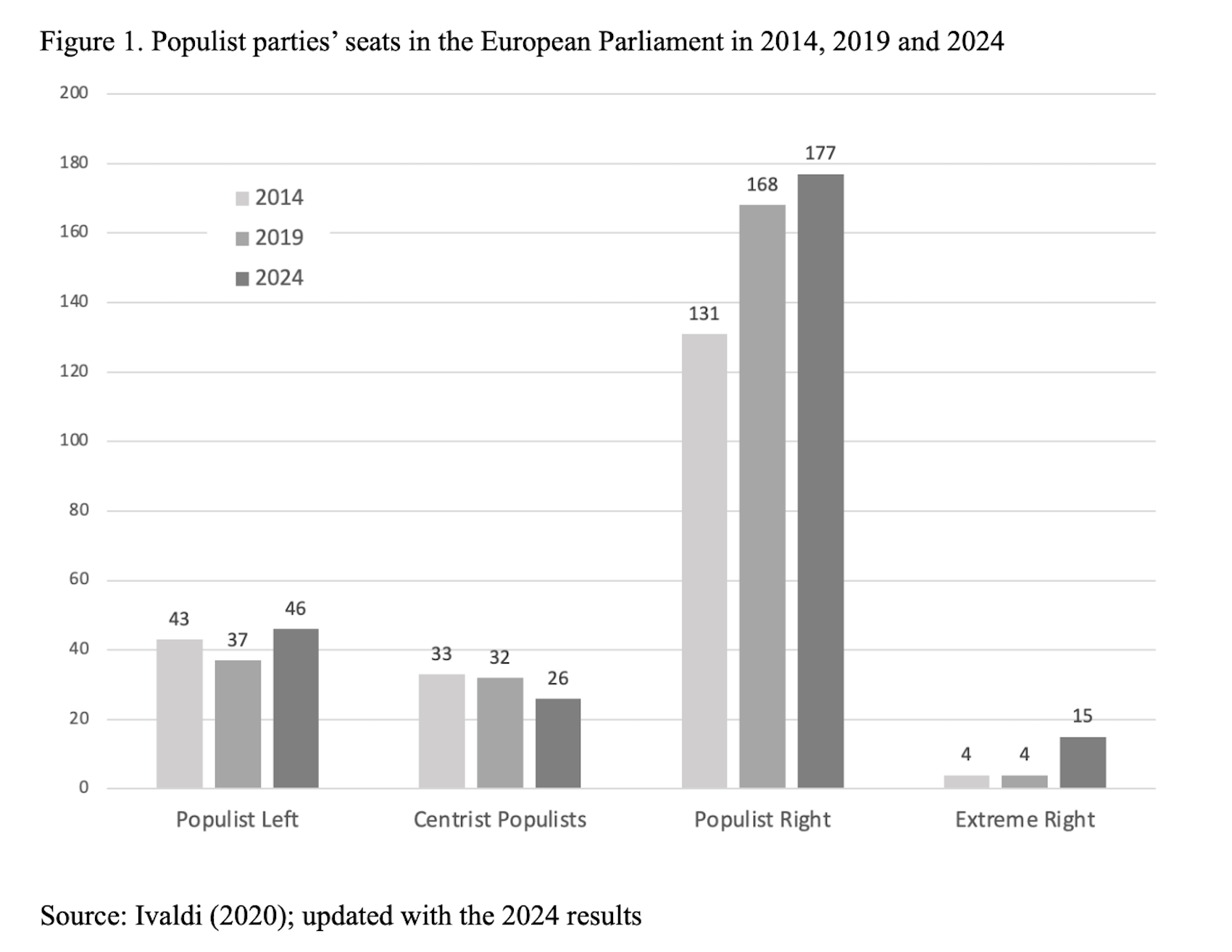

Rather than showing a new wave of populism, the results of the 2024 European elections have essentially confirmed the electoral consolidation of the populist phenomenon in Europe. In 2019, taking all groups together, populist parties had won 241 seats, representing about a third (32%) of all 751 seats in the European Parliament. In 2024, these parties won 263 of the 720 seats – approximately 36% (see Figure 1, Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Such results reflect the rise in support for populism in recent national elections as well as the increase in the number and geographical spread of populist parties across Europe. Based on the delineation of populism in the country chapters, no less than 60 populist parties across 26 EU member states gained representation in the European Parliament in June 2024. In comparison, a total of 40 populist parties had won seats in 22 EU countries in the 2019 election.

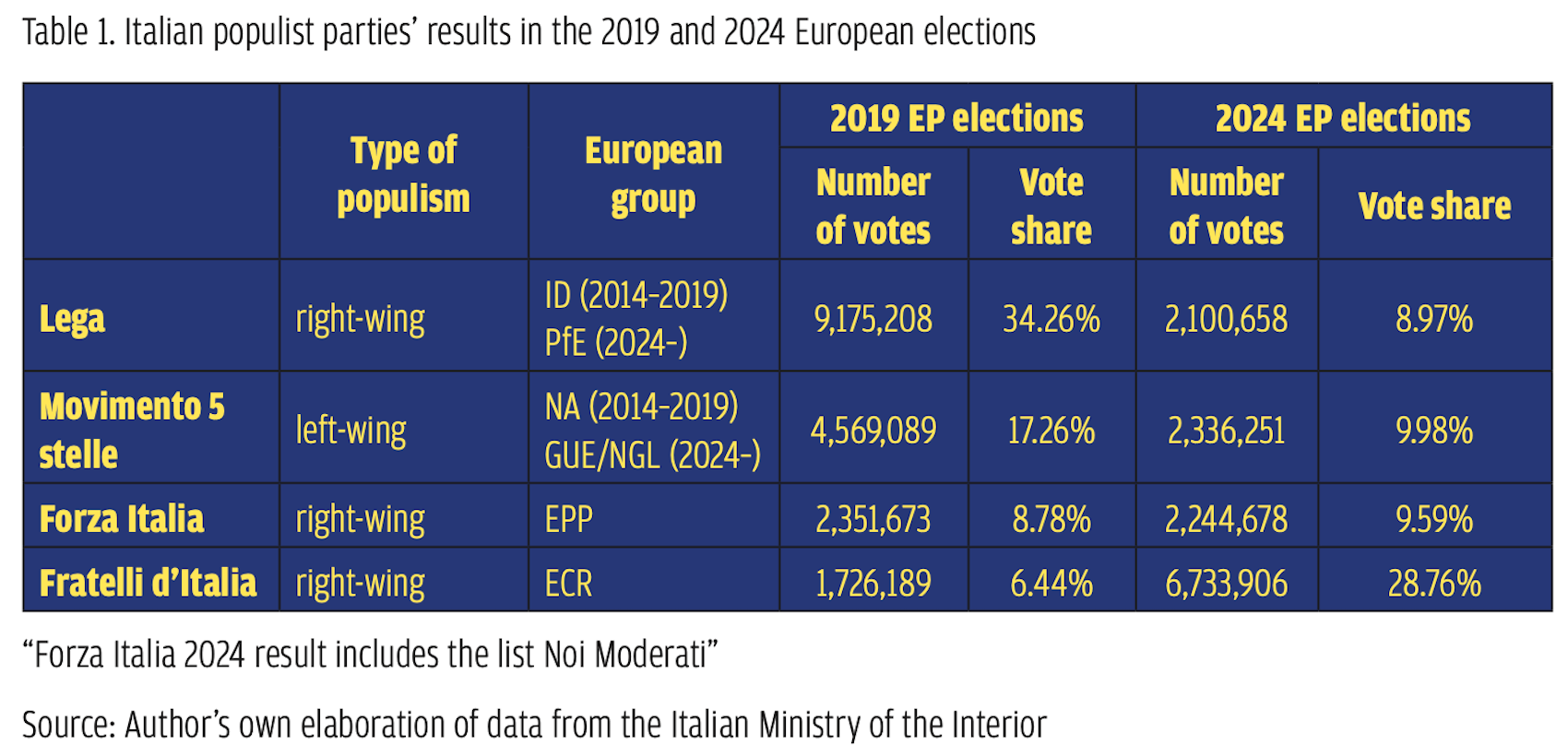

Populist party performances varied, however, across countries and different brands of populism. Moreover, the new distribution of seats should not mask distortions due to the relative weight of national representations in the European Parliament. In June 2024, the largest contingents of populist MEPs came mainly from the populist right in the more populated European countries, in particular from France’s Rassemblement National (30 seats), Fratelli d’Italia (24 seats), the Polish PiS (20 seats), the German AfD (15 seats) and Hungary’s Fidesz (11 seats). In the populist left, the largest contingent came from France’s LFI (9 seats). For centrist populist parties, the largest delegations were elected in Italy with the M5S (8 seats) and in the Czech Republic, where ANO received seven seats.

Asymmetrical populist performances

The results of the 2024 European elections have essentially attested to the consolidation of the populist right, while left-wing and centrist populist parties have received comparatively less support across Europe.

The populist right has established its presence in virtually all EU member states – there are no fewer than 50 such parties in Europe. Right-wing populist parties have done particularly well in countries such as France, Italy, Poland, Hungary, Belgium, Austria, Bulgaria, Romania, and the Netherlands; in many countries, the populist right-wing scene is made up of two, three and sometimes more parties.

There has also been a diversification of the populist right with the emergence of new actors. Alongside the major established players, new parties have emerged, including the Danish Democrats (DD), Latvia First (LPV), Chega in Portugal, the EL and Niki in Greece, the AUR and SOS in Romania, and the Czech Přísaha and PRO. In Lithuania, a populist radical-right politician and his party TSS made a breakthrough, gaining a seat in the EP for the first time.

Other movements have disappeared or been replaced by new populist parties. This is particularly true in Central and Eastern Europe, where party systems traditionally remain more fluid. The Bulgarian Ataka, long represented in the national assembly and the European Parliament, has all but disappeared since 2021, only to be replaced by Vazrazhdane. Golden Dawn, which came third in the 2015 elections in Greece, practically disappeared by 2019 when it failed to enter the national parliament. Its leadership was subsequently imprisoned following a prolonged trial on charges of running a criminal organization. Although the party disappeared, its ideology and electorate were easily picked up by EL, which has been represented since 2019 both in the national and in the European parliaments. Interestingly, small extreme right-wing-wing anti-immigration parties (i.e., the Irish Freedom Party, National Party, Ireland First and The Irish People) have surfaced in a country like Ireland, which has traditionally been more immune to far-right populism in the past, suggesting that the immigration issue has acquired more resonance in Irish politics in recent years.

Altogether, parties of the populist right won 177 seats, making up about a quarter (24%) of all 720 seats in the new European Parliament, an increase on their previous performances in 2019 –168 seats out of 751, that is about 22% (see Figure 1). Amongst the biggest winners were the French RN, the Italian Fratelli d’Italia, the FPÖ in Austria, the VB in Flanders, the Slovenian Democratic Party, the AUR in Romania and the National Alliance in Latvia, which all saw a significant rise in electoral support in the 2024 European elections. Let us also note that the 2024 elections have seen the rise of extreme right-wing nationalist parties across a number of EU member states, as illustrated by the electoral success of Vazrazhdane in Bulgaria, the Confederation in Poland, Hnutie Republika in Slovakia, ELAM in Cyprus, and Domovinski Pokret (DP) in Croatia. Altogether, parties that may be classified as ‘extreme right-wing’ won 15 seats in the European Parliament, significantly increasing their presence since the 2019 elections, where the extreme right-wing had received only 4 seats.

Such a wave of support for right-wing populists has been far from uniform, however, as a number of those parties have suffered losses across Europe. In Portugal, Chega lost nearly 783.000 votes from its general election tally, down to 9.8% of the vote. In Spain, while clearly improving its results from the 2019 EP elections, Vox lost significant support when compared with the 2023 general elections. In Sweden, the SD fell far behind the result of the 2022 parliamentary election. Fidesz in Hungary lost 2 seats despite winning the elections, facing a serious challenge by the new opposition party Tisza. Although PiS and Konfederacija collectively attracted almost half of the votes, PiS lost 9 seats in the EP – the biggest reversal in support in its history.

Compared with their right-wing counterparts, the parties of the populist left have been comparatively less successful, although they have somewhat improved their performance from five years ago. As Figure 1 shows, the populist left won a total of 46 seats in the new European Parliament in June, which represented just over 6% of all 720 seats. This result compared with 37 seats (about 5%) in the previous Parliament. As was the case for the populist right, left-wing populist party performances varied substantially across countries.

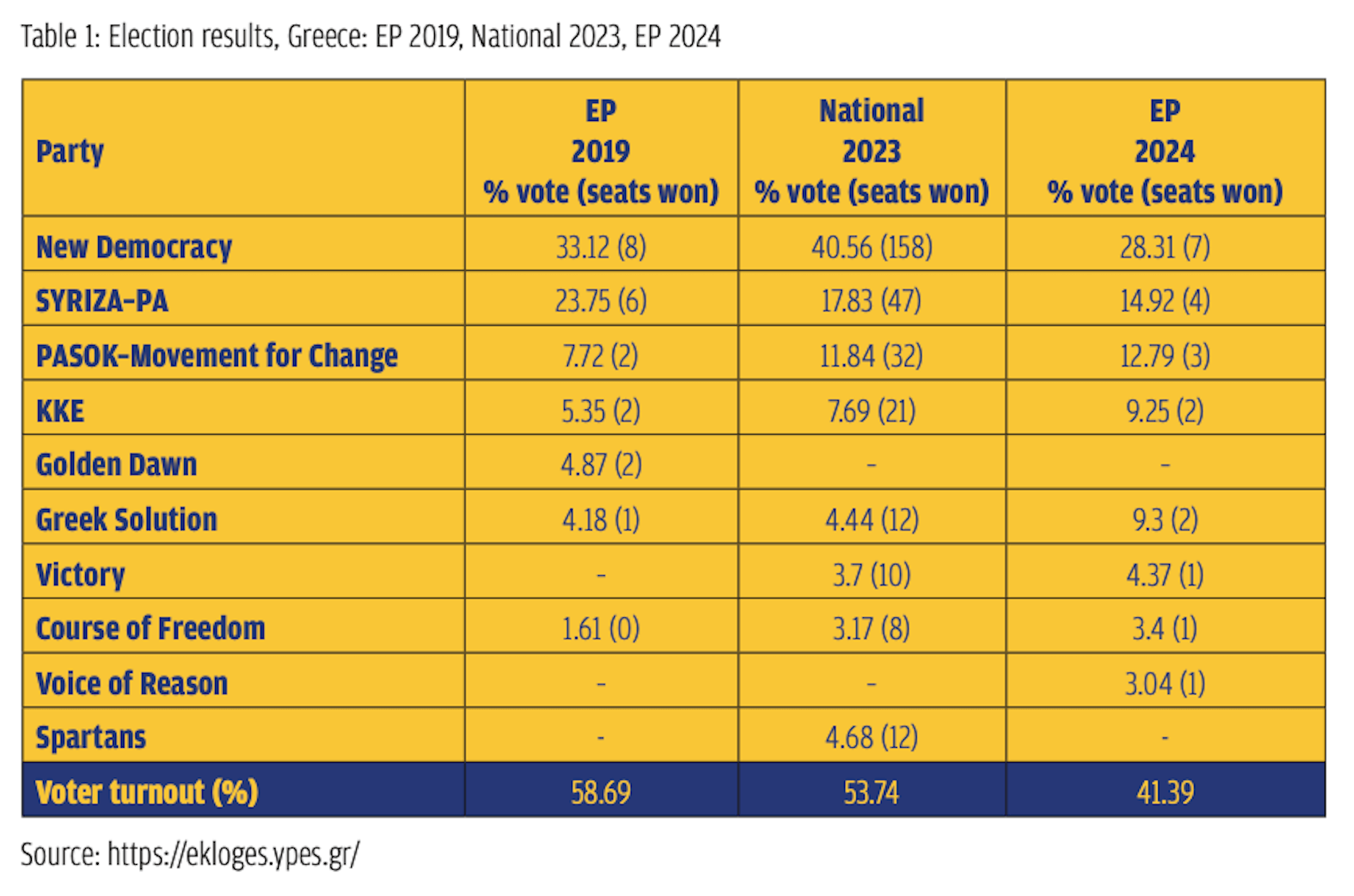

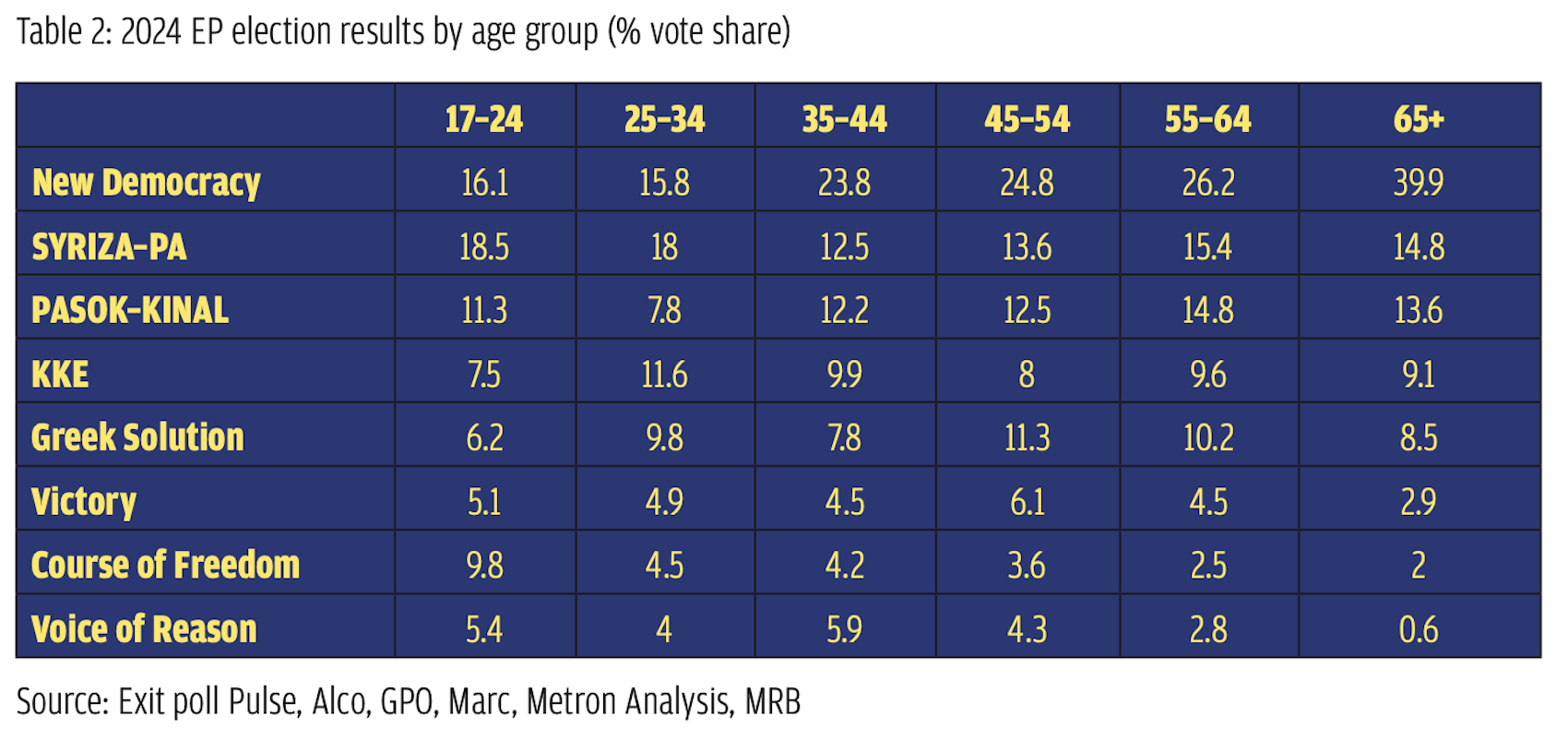

In countries such as Ireland, Greece, the Netherlands and Spain, there was a drop in support for the populist left, reflecting the more general decline in support for those parties since the 2008 financial crisis. In Ireland, Sinn Féin suffered significant losses, seeing much of his previous support going to independent or small-party candidates. In the Netherlands, the SP received a mere 2.2% of the vote, showing a decline since its success in 2014 when it had obtained almost 10% of the vote. The Spanish Podemos only received 3.3% of the vote, compared with 20% in 2016 –in alliance with Izquierda Unida (IU) at the time. In the case of Podemos, such decline reflected a variety of factors, including government participation and the recovery of macroeconomic indicators. In Greece, Syriza lost about 3 percentage points on its score in the June 2023 general election, down to 14.9% of the vote, although EKK maintained its 2 MEP seats, as well as representation in the national parliament.

In countries like Belgium and France, there were mixed performances for the populist left. The progress of the Belgian PTB–PVDA was asymmetrical, with the party making more significant gains on the Dutch-speaking side, almost doubling its score. In France, Mélenchon’s left-wing populist LFI won 9.9% of the vote, which represented a gain of 3.6 percentage points on its previous result in the 2019 EP elections, yet far lower than Mélenchon’s performance at 22% in the 2022 presidential election.

Support for the populist left rose, on the other hand, in Nordic countries such as Denmark and Finland. The Danish Red-Green Alliance won 7% of the vote (+2 percentage points compared to the legislative elections of November 2022). In Finland, the biggest surprise came from the Left Alliance (VAS), which came in second with 17.3% of the vote and three seats as opposed to one in the previous parliament. In Slovakia, SMER managed to regain political control in the 2023 national elections and increase its representation in the European Parliament from 3 to 5 seats – a major comeback for Robert Fico, who survived an assassination attempt just a month before the EP elections.

Finally, the 2024 European elections have confirmed centrist populism as a relatively marginal political phenomenon, essentially concentrated in Central and Eastern Europe. In June 2024, only 26 seats were won by centrist populist parties, making up just under 4% of all seats in the new European Parliament, which was very close to those parties’ performances five years ago (32 seats representing just over 4%).

While well-established centrist populist parties such as ANO in the Czech Republic and GERB in Bulgaria managed to secure their electoral support from the previous national elections, winning 7 and 5 seats, respectively, other centrist populist parties performed less well. In Bulgaria, PP lost heavily on their previous performance in the April 2023 elections and secured only two seats in the new European Parliament. This was also the case with the Darbo Partija in Lithuania, which lost most of its support from the last general election and failed to capture a single seat in the EP. Other parties’ results oscillated, such as for ‘There is Such a People’ in Bulgaria, which won the July 2021 early national elections, disappeared from the national parliament in the early national elections in 2022 and reappeared in 2023, gaining a single sear in the EP at the 2024 elections. New centrist populist parties, such as the Czech Přísaha, managed to surpass the threshold, sending one MEP to Brussels. Others, such as Stabilitātei! in Latvia and OL’aNO and SaS in Slovakia, failed to pass the threshold at the European Parliament elections despite gaining representation in the national parliaments in 2022 and 2023, respectively.

In Italy, the results of the 2024 elections have attested to the continuing electoral decline of the M5S. The party received 10% of the vote and eight seats, significantly losing ground from its previous performances in the 2019 European (17.1% of the vote cast) and 2022 general elections (15.4%).

A regional divide?

As mentioned earlier, the distribution of populism across Europe shows a regional divide (see Table 1). In the 2024 European elections, left-wing populism was primarily found in Western Europe, where 13 of those parties were in competition, as opposed to only 2 in Eastern and Central Europe (i.e., SMER in Slovakia and Levica in Slovenia). Conversely, centrist populism was essentially located in CEE countries, which had nine of those parties, as opposed to only two in Western Europe (i.e., the M5S in Italy and the BBB in the Netherlands). Populist radical-right parties were in the majority, and they were predominantly found in Western European countries (21 as opposed to 12 in CEE). Finally, the regional distribution of populism shows the rise of extreme right-wing parties in countries of the former Soviet Union, with no less than 11 of those parties competing in the 2024 European elections, as opposed to only one (ELAM in Cyprus) in the western part of the EU.

Table 1. Number of parties by populist family across Western and Eastern Europe

| Countries | Left | Centrist | Right | Radical Right | Extreme Right | Total | |

| Eastern | 11 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 38 |

| Western | 15 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 1 | 39 |

| 26 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 33 | 12 | 77 |

Such an uneven distribution of populism makes it difficult to accurately evaluate regional differences in populist party electoral support across Western and Central and Eastern Europe. As the country chapters clearly illustrate, there was a significant amount of variation in the electoral performances of populist parties in the 2024 European elections, both across and within regions. Moreover, no less than 27 populist parties were new parties that had not run in the 2019 European elections, thus rendering the analysis of change in populist party support even more difficult.

Table 2. Average electoral support by populist party family across Western and Eastern Europe

| Average % of vote 2024 European elections and change from most recent national election | |||||

| Left | Centrist | Right | Radical Right | Extreme Right | |

| Eastern | 29.5* | 9.36 | 1.21 | 14.61 | 5.65 |

| Change | (+1.1) | (–3.3) | (+0.9) | (+1.4) | (+1.8) |

| Western | 7.28 | 7.69* | 10.67* | 11.63 | 11.19* |

| Change | (–0.2) | (–2.4) | (+2.0) | (+0.9) | (+4.4) |

Source: Compiled by the authors based on 2024 EP election data.

* These results should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of parties (n ≤ 2).

Table 2 shows the mean electoral support for populist parties in the 2024 European elections and the change from the most recent general election. The data are broken down by region and populist party family. Because of such heterogeneity, the data in Table 2 should be taken with caution. These data confirm, however, that centrist and left-wing populist parties have lost ground on average in the 2024 European elections compared with their performances in the last general election in their respective country and that such decline was visible in both Eastern and Western European countries. On average, the populist radical right has made progress across both regions: +1.4 percentage points in CEE countries and +0.9 percentage points in Western Europe, again bearing in mind that there was substantial variation in party performances within each region. Finally, the data show that extreme right-wing ultra-nationalist movements have made gains in Eastern Europe, winning an additional 1.8 percentage points on average on their previous performance in the last general election.

Overall, with all limitations in mind, the data do not show a clear regional divide in terms of populist party performances in the 2024 European elections but rather point to the diversity of populist manifestations and variation of their electoral performances within each region. At the country level, the German case illustrates a more striking regional pattern as all three populist parties were much more successful in the eastern states, reflecting the multi-faceted legacy of the GDR and the political impact of the shock and aftermath of the transformation in the 1990s.

Diverse drivers of populism in the EP elections 2024

Across Europe, the popularity of populist movements is rooted in the ‘polycrisis’ to which EU citizens have been exposed since 2008 – the financial crisis, the 2015 refugee crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and now the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Fidesz’s electoral slogan, ‘No migration, no gender, no war!’ succinctly captures the division lines not only between populists and non-populists but also among populists from the left, the centre, and the right and even within those subcategories. In Austria, the polycrisis amalgam was perfectly summed up by the FPÖ’s slogan in the run-up to the vote: ‘Stop European chaos, the asylum crisis, climate terror, warmongering and Corona chaos’. In Italy, the multiple crises have led to increased opposition to the EU. In France, since 2012, support for the RN has been fuelled by feelings of economic alienation mediated by cultural concerns over immigration and strong anti-elite sentiments.

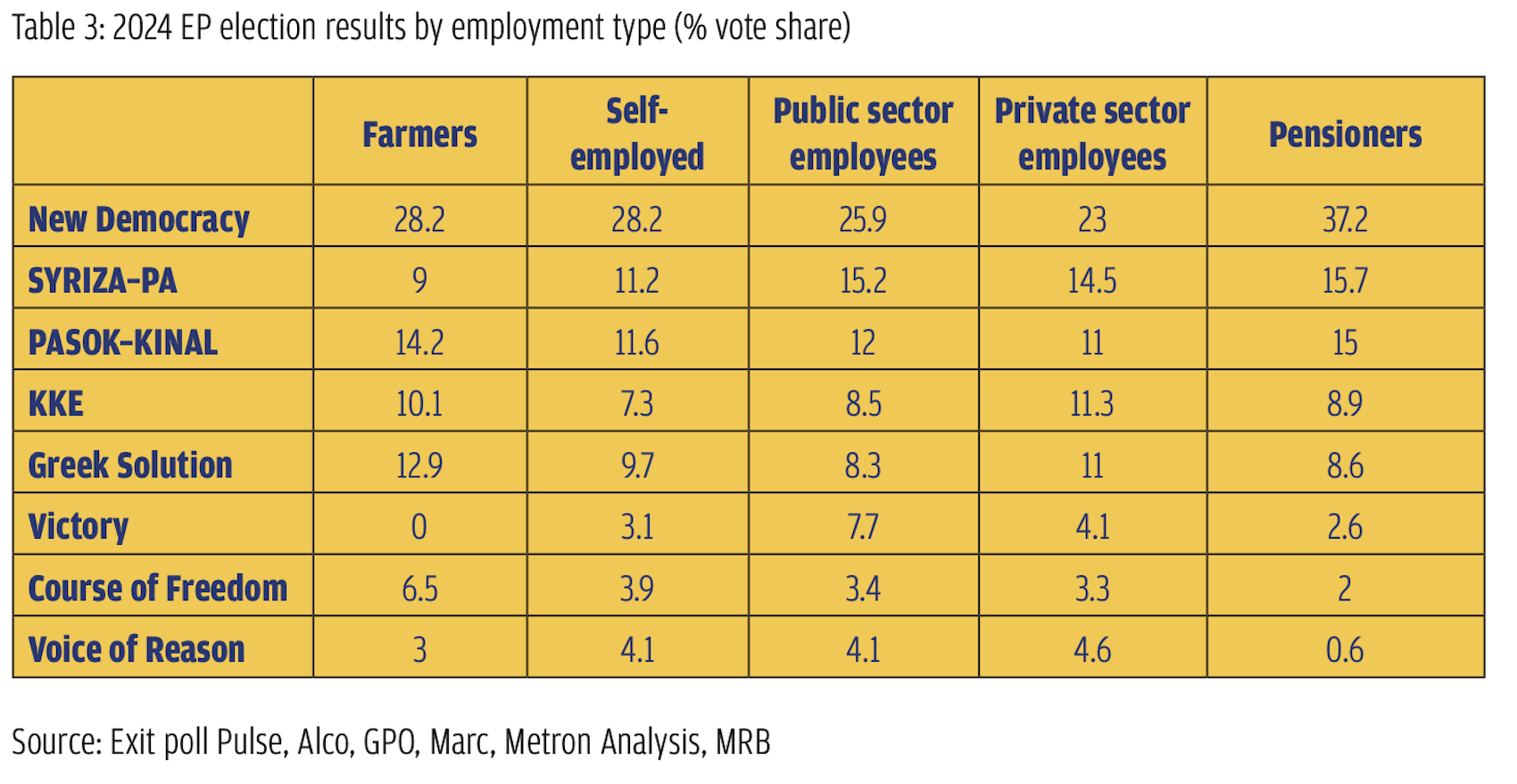

However, this polycrisis has played out differently in each country. Belgium illustrates such differences: the political debate in Flanders saw more focus on migration, law and order and public finances, whereas, in French-speaking Belgium, the focus was more on energy, civil rights and work. Immigration issues have become more salient in countries such as Cyprus, which is the first country in the EU to move to per capita applications for asylum. This has led to Euroscepticism and discontent in relation to the EU’s management of immigration. In contrast, in Sweden, immigration was less significant than it had been in both the previous European election and the Riksdag election of 2022. In Greece, domestic – rather than European – issues dominated the campaigns, including the economy, inflation and the cost-of-living crisis, with populists both from the right and the left cashing in on economic decline and regional disparities. In Austria, the FPÖ focused on migration, the war in Ukraine, climate change and, notably, the COVID-19 pandemic. Amongst those four, migration was the most important issue in the campaign. In Latvia, populist parties campaigned around the war in Ukraine, the Green Deal and its economic impact, and the defence of traditional family and Christian values, opposing progressive, liberal ideals in Brussels, including LGBTQ+ rights. Opposition to LGBTQ+ rights was typical for most of the radical-right populists, including in Bulgaria, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. LGBTQ+ rights were countered with arguments on religion and traditional family values, including criticisms of political correctness and limiting the freedom of speech. By contrast, some left–populist outfits (such as the Greek KKE) have been defenders of LGBTQ+ rights and socially progressive in general.

Economic uncertainty as a common driver of populism

Beyond such variation, the economic context has heavily weighed on public opinion and has fuelled frustration and anger around the rising cost of living in many countries. Economic fears clearly dominated the campaign in France, creating a propitious context for populist politics across the board. The Denmark Democrats have made significant inroads in rural areas where voters feel neglected and left behind. In Germany, the AfD continued to push their core issues — first and foremost immigration, but also the economic impact of the war on Germany, climate denialism and hard Euroscepticism. To the left, populist parties have also politicized the economic crisis. In Ireland, support for Sinn Féin rose in the 2010s as it adopted a more populist approach combined with a strong focus on economic issues. The acuteness of the housing crisis also helped the party. Sinn Féin had campaigned strongly on the housing issue, and it was this that brought it increased support among young progressive voters.

Luxembourg serves as a counterexample here. Public opinion data show that compared to the EU average, Luxembourgers were far more satisfied with their economic situation and the EU, and they felt much better off economically and also had much higher levels of trust in their national government and the EU. The fact that populists enjoyed more support in rural areas and among the less educated in the Czech Republic and Romania, among others, further indicates the importance of economic uncertainty as a driving factor.

Immigration and refugees

In many cases, the populist radical right has capitalized on insecurities linked to immigration and asylum seekers, which was a key issue in countries such as the Netherlands, Germany, Hungary, Poland and France. Germany had accepted more than a million Ukrainian refugees after the 2022 attack, which brought the issue of immigration back onto the agenda in 2023 after its salience had been low for several years. In France, next to inflation, immigration emerged as the second most salient issue, followed by law and order. In Flanders, the immigration agenda has been particularly favourable to the populist radical parties such as the VB. Immigration represented a key focus for all right-wing populists (EL, FL, and Niki) in Greece. In Austria, The FPÖ rejected the EU’s Pact on Migration and Asylum and the mandatory distribution of asylum seekers across the EU, calling instead for a ‘Pact on Re-Migration’. In Italy, the populist governing coalition of FdI, Lega, and Forza Italia prides itself on the migration deal signed with Albania that aims to relocate immigrants arriving in Italy to Italian-operated refugee centres in Albania. The Italian prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, has further succeeded in pushing for EU-wide agreements with North African countries that envision limiting the flow of migrants in exchange for financial assistance.

Immigration issues were also prominent in Eastern and Central European countries. In the Czech Republic, populists from the centre and the right framed migration in security terms, rejecting the EU Pact on Migration, highlighting the so-called “no-go zones” where women are at risk and Islamic minorities have brought crime, terrorism and the domination of Sharia law. In Poland, migration has been a major focus of both PiS and Konfederacija. The influx of refugees from Ukraine has provided fertile ground for populist discourses. While the PiS government had initially embraced Ukrainian refugees, the prolonged war and the sheer number of refugees resulted in a backlash with time and fervent opposition against the EU’s Migration Pact, which was labelled the ‘Trojan horse of Europe’. The governing SMER party in Slovakia has similarly criticized the Pact on Migration and Asylum and opposed compulsory relocation schemes, proposing measures in the country of origin instead.

Such rising salience of immigration issues may account for the decline in support for left-wing populism. In Ireland, for example, the 2024 European Parliament elections came on the back of a rise in the prominence of immigration as an issue. Sinn Féin’s falling support, then, can be seen as the party’s failure to address such issues despite trying to change its discourse on the pressure that recently arrived asylum seekers put on social services. Similarly, in the Netherlands, the inability of the SP to attract economically left-wing and welfare-chauvinist voters may be seen as a consequence of the party’s lack of commitment to an anti-immigrant stance. In Italy, similarly, M5S has lost support also due to its inability to address the migration problem.

Populist polarization over climate change and the green transition

There has also been a backlash against the European Green Deal, with populist radical-right parties attacking the environmental transition as being “punitive”. Right-wing populist parties’s scepticism about climate change and hostility to low-carbon energy policies has been well documented in the literature (Lockwood and Lockwood, 2022). The recent study by Forchtner and Lubarda (2023) suggests that right-wing populist parties generally claim that climate policies should not harm the economy and jobs and that such parties most effectively perform as defenders of the nation’s economic well-being.

In Flanders, the VB opposes further enlargement and positions itself against the interference of the EU in the national politics of illiberal democracies, as well as against EU policies in terms of climate and agriculture. In Luxembourg, the ADR party has prioritized the preservation of the combustion engine, more generally opposing green politics. The Finns Party has been the Eurosceptic party in Finnish EP elections, promoting an agenda opposed to the EU, immigration and climate change policies. In the Netherlands, the PVV vehemently called for opt-out possibilities for the Netherlands regarding asylum seekers and migration and relaxing obligations with respect to climate change, especially nitrogen. The Austrian FPÖ demands a stop to the European Green Deal, the EU Nature Restoration Law, and the scheduled ban on combustion engines. In Poland, the European Green Deal has been criticized both by PiS and Konfederacija as an ideological project of EU elites aimed against ordinary citizens. Both parties have highlighted the high prices of energy, transport and agriculture to ordinary Poles. The European Green Deal was similarly criticized by right-wing populists in Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania, to name a few.

In contrast, left-wing populist parties have been taking up environmental issues, and they have endorsed an agenda of green transition (Duina and Zhou 2024). Parties such as LFI in France and Podemos in Spain have placed environmental issues at the core of their political platform while blaming political and economic elites for the environmental crisis. In Italy, Movimento 5 Stelle’s electoral platform emphasizes anti-austerity measures, public healthcare defence, anti-corruption efforts, environmental protection, and labour issues, including introducing a minimum wage and a 32-hour workweek. SMER is a notable exception in the left–populist camp, as it has vehemently criticized the Green Dea, labelling it an “extreme environmental initiative” pushed through by “Eurocrats with no accountability” and rejecting the target of reducing emissions by 55% by 2030.

Such a populist divide over climate change is most visible in France, where radical right-wing populist parties such as the RN and Reconquête clearly oppose the European Green Deal and play with climate-sceptic themes to sway voters most affected by the economic cost of the green transition. In contrast, the left-wing populist LFI has adopted an eco-socialist and ambitious green transition agenda, championing the fight against climate change (Chazel and Dain, 2024). We see a similar divide in Italy: Lega’s platform focuses on halting the EU’s technocratic and centralizing drift and restoring the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality. Key proposals include rejecting the Green Deal, ending austerity policies and protecting Italian production chains. In contrast, the M5S has put environmental protection and green transition policies at the core of its electoral platform. In Denmark, the left-wing populist SF has spearheaded the call to accelerate decarbonization efforts and implement policies to achieve concrete results quickly, given the urgency of the climate crisis. In contrast, the populist right-wing, led by the DF and the Denmark Democrats, opposed environmental regulations, which they believed would harm the competitiveness of Danish agricultural products in the European market.

In Germany, on the other hand, the government’s green transition policies are strongly opposed by populist parties across the board. These parties also sided with large-scale farmers’ protests against some cuts to agrarian subsidies that eventually forced a government U-turn. The AfD continued to push climate denialism and hard Euroscepticism. Both AfD and BSW will likely vote against any policies related to the ‘green transformation.’

Finally, the ecological divide is found across other types of populism. In the Netherlands, for example, the BBB typically pits ordinary citizens and farmers against ‘oat milk cappuccino drinking’ city dwellers and unresponsive politicians from the major cities in the west of the country (the so-called Randstad). BBB’s core issues centre around support for farmers and opposition to radical climate policies. Similarly, in Romania, the SOS emphasized the protection of farmers and agriculture workers, criticizing EU product regulations, advocating for Romanians’ rights to continue using traditional energy sources like firewood and natural gas, and demanding the reopening of coal mines. In the Czech Republic, the European Green Deal has been rejected by both the ANO and the SPD. While ANO accused Brussels of committing ritual suicide, the SPD attacked the reduction of combustion engines by placing a former racing driver at the top of its electoral list.

Gaza and the Israel–Hamas war

The Israel–Hamas war and the humanitarian crisis in Gaza have provoked diametrically opposed reactions among populists from across the political spectrum. The conflict has featured much more prominently in political discourse in Western Europe than in Central and Eastern Europe, where the war in Ukraine has taken precedence.

France is a good illustration of such a divide. French lead candidates show deep splits over recognition of a Palestinian state. Left-leaning contenders, from the Communists to the social democrats, are clearly in favour of a ‘two-state solution’, while the French far right, in a break with the past, now supports Israel. Marine Le Pen and RN President Jordan Bardella joined pro-Israeli protests, blaming left-leaning forces for allegedly failing to condemn the 7 October attacks. The LFI, by contrast, has taken a pro-Palestinain position, calling for sanctions against the Israeli government, an embargo on the shipping of weaponry and artillery, an end to the 2000 EU-Israel Association Agreement, and the immediate recognition of a Palestinian state. Mélenchon and members of LFI were accused of antisemitism for declining to condemn Hamas as a terrorist group.

Overall, voters of left-wing forces were more concerned about war in Palestine than Ukraine and were more likely to support the Palestinian cause. This concern was particularly visible among Podemos voters, as well as KKE supporters in Greece. Yet, some right-wing populists have also sided with Palestine and not with Israel, including the Belgian PTB–PVDA and the Irish PBP. Romanian SOS leader Șoșoacă has been accused of antisemitism for her controversial remarks. For instance, during a joint session of parliament dedicated to the Day of Solidarity and Friendship between Romania and Israel in May 2024, Șoșoacă complained that this day should serve to commemorate Romanian martyrs from communist prisons, criticizing what she viewed as an incorrect focus on antisemitism. She protested that Romania saved over 400,000 Jews during the Second World War. Vazrazhdane’s leader, Kostadin Kostadinov, has also been highly critical of Israel, although acknowledging the terrorist attack of Hamas and advocating for a two-state solution.

Other right-wing populists have firmly defended Israel. Chega claimed that Netanyahu’s government was entitled to ‘neutralize the threat’ and was the only parliamentary party to decline to join calls for a ceasefire. In Germany, a knife attack by an Afghan man left a police officer dead just days before the election, triggering a fresh debate about immigration, Islamism and the longstanding policy against deportations to Afghanistan. The anti-Islam stance was also important for the Czech SPD, which has been a stalwart defender of Israel.

Ukraine and Russia

The outbreak of the war in Ukraine resulted in diverse responses by populist parties. Many populists on the right, especially in Western Europe, initially distanced themselves from Putin and cooled off their usual pro-Russian stance. Others, on the contrary, became even more pro-Russian (Ivaldi and Zankina, 2023). Such diversity can be explained by specific geostrategic and historical factors, including geographical proximity to Russia, past conflicts, cultural proximity or trade relations.

Some of the most vehement defenders of Russia in the West have been the AfD and FPÖ, which have denounced their respective governments’ support for Kyiv, accusing them of ‘warmongering’. The AfD has a longstanding association with Russia, repeatedly voicing sympathy for Putin and his regime. Although the party toned down its statements immediately after the February 2022 attack, it has since highlighted the economic consequences of the war and the sanctions for Germany, reinventing itself as a party of “peace”, even adopting the classic dove symbol. The BSW took an even more pro-Russian stance than the AfD, with its leader Wagenknecht routinely claiming that the US and the collective Western block a peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine for reasons of their own. BSW’s 20-page manifesto mentions sanctions 14 times, depicting them as harmful to Germany while having no effect on Russia itself. The FPÖ criticized the EU’s support for Kyiv, calling for an immediate end to financial and military aid to Ukraine and abolishing sanctions against Russia due to their detrimental effects on the economy. The Austrian government, in turn, was criticized for a breach of the country’s constitutional obligation of neutrality. The Dutch FvD has also propagated a pro-Russia and pro-Putin line, as did the Swedish SD. SD’s leader Åkesson stated that there is an upper limit to how much support Sweden should give to Ukraine, while the party’s top candidate, Charlie Weimers, suggested that their own party group, ECR, should be open to cooperating with parties in the ID group, whose stance on Russia has been characterized as relatively friendly. The Irish PBP has taken positions that are less in tune with popular opinion and are often seen as pro-Russian, including calls for Ukraine to enter peace talks.

Putin has enjoyed even more support in Central and Eastern Europe, including in Hungary, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Orbán’s campaign made the war in Ukraine its centrepiece. He used fear-mongering to build a Manichean narrative where anybody failing to vote for Fidesz was part of the ‘pro-war’ camp, accusing the Hungarian opposition of carrying out the demands of its international financiers in Brussels and Washington. Orbán repeatedly blamed the EU for wrongdoing and claimed that because of the incompetent leadership in Brussels, ‘instead of peace, we have war, instead of security we have a rule-of-law ruckus, instead of prosperity we have financial blackmail’. The Bulgarian Vazrazhdane and its leader, Kostadin Kostadinov, have been stark defenders of Putin to the extent of reaching comical proportions. Kostadinv is widely known in the country as ‘kopeikin’, referring to the Russian coin currency. His rallies feature more Russian than Bulgarian national flags. He frequently travels to Moscow, and his party is known to be funded by Putin (Zankina, 2024). The Czech SPD has become one of the most vocal anti-Ukrainian voices following Russia’s 2022 invasion, as did the newly emerged SOS in Romania. SOS’s leader Șoșoacă was declared ‘Personality of the Year’ in 2021 by Sputnik. She asserted that Europeans and Americans aim to destroy Russia and argued that Ukraine illegally occupies territories, including some that rightfully belong to Romania. The left–populist SMER in Slovakia, in turn, has called for a halt of all military assistance to Ukraine in its defence against Russian aggression and for a more neutral stance toward Russia. SMER blamed the EU for ‘prolonging war in Europe’ by supporting Ukraine.

In contrast to such support for Putin, a number of parties across Europe have adopted a pro-Ukraine position. In Finland, for example, support for Ukraine has been almost unanimous, including by the Finns Party, which has criticized Putin’s Russia, expressing strong support for Ukraine. Similarly, the Danish People’s Party and the Denmark’s Democrats are declaredly pro-Ukraine. In Portugal, Chega also aligned with most mainstream parties, adopting a pro-Ukraine position. The Croatian DP has expressed firm solidarity with Ukraine and the Ukrainian people, drawing parallels between Croatia’s Homeland War (1991–1991) and Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Although Sinn Féin has often blamed the West for being unnecessarily aggressive toward Putin, with the invasion of Ukraine, the party stood firmly behind Ukraine, although it continued to abstain on aid packages in the EP.

Many parties struggled to take a clear stance, expressing ambiguous positions. The RN, for example, has significantly moderated its attitude. Le Pen said her only ‘red line’ on Ukraine was stopping France from becoming a ‘co-belligerent’ in the conflict via the use of long-range French missiles against targets on Russian soil. French far-right leader Jordan Bardella said he backed Ukraine’s right to defend itself against Russia, but if elected prime minister, he would not provide Kyiv with missiles that would allow it to strike Russia’s territory. He also said he would stand by France’s commitments to NATO if he became prime minister. In Germany, the Left’s manifesto for the European elections also reflected ambiguity.

On the one hand, the document is highly critical of the US and NATO and even claims that the eastern enlargement of NATO has “contributed to the crisis”. On the other, it highlights Ukraine’s right to self-defence, condemns the attack as a war crime, and demands the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory. The Dutch PVV supported the strengthening of defence, however, without singling out Russia as the main threat. Populists in Latvia took similarly ambivalent positions on Russia. S! refused to blame Russia for the invasion, arguing instead for ‘peace’. The LPV initially denounced Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but subsequently softened its stance, advocating for the need for negotiations, peace and the renewal of economic relations with Russia – a position also adopted by SV, which primarily appeals to Russian speakers. The Romanian AUR has taken nuanced positions. While denouncing Russia’s interference as a significant obstacle to unification with Moldova, the party also criticizes Ukrainian discrimination against ethnic minorities, particularly Romanians.

Multiple Factors of populist performances across EU member states

As the individual chapters illustrate, beyond differences in issue salience across countries, there were a variety of political factors that may account for differences in populist party electoral performances in the 2024 European elections.

National cycle

Such performances may be first related to the location of the EP elections in each country’s national political cycle. The analysis in this report corroborates studies that show that party performances in European elections are mediated by the time of these elections in the national electoral cycle, that government parties lose support in EU elections, especially during the midterm of a national parliamentary cycle, and that opposition parties may benefit from this (Hix and Marsh 2007).

In Germany, the 2024 European election saw devastating results for the governing coalition of the Social Democrats (SPD), Greens, and Liberal Democrats (FDP). The so-called “progressive coalition” and its policies have been deeply unpopular, and the radical-right AfD was the main beneficiary of this discontent. In France, political protest and anti-incumbent sentiments were key to populist voting across the spectrum: over two-thirds of RN voters said they essentially voted to manifest their opposition to the President and the Government, and it was 53% among LFI voters. In the Netherlands, the results of the 2024 European elections for populist parties in the Netherlands were intimately related to the fall of the Rutte IV government in the Summer of 2023 and the outcome of the subsequent national elections on 22 November 2023, which saw a rise in support for the PVV. In Poland, the governing coalition, which managed to take power away from PiS in 2023, saw a decline in its support. While PiS lost 12 MEP seats, it did regain some of its support compared to the 2023 national election. In Slovakia, SMER, which managed to take back power from OL’aNO in the 2023 national election, lost some of its support in the EP elections, coming second after the liberal Progressive Slovakia (PS). In Hungary, while Fidesz won the elections, it lost some support and faced an unprecedented challenge by a new political party that reshuffled the power balance in the opposition.

The country chapters also find evidence of another key element of the ‘second order’ model that has been applied to European elections since the early 1980s, which is that voters typically make judgements about national political issues in those elections (Reif and Schmitt, 1980). In many countries, the 2024 European elections were fought over domestic rather than European issues and populist parties often played the national card. In Spain, for example, the number and relevance of ongoing national-level political issues often sidelined European ones during the 2024 campaign. In Portugal, Chega’s manifesto proposals were mostly domestic; European-level proposals were scarce despite a broader media agenda focused on European immigration, defence and EU enlargement. In Germany, domestic actors and attitudes dominated the campaign, with only a minority of populist voters saying that “Europe” was more important for their decision than “Germany”, particularly AfD supporters who were more inward-looking and more Eurosceptic than the BSW’s. In Greece, domestic issues dominated, with election results representing an anti-government protest vote. This was also the case in the Czech Republic, where many voters supported populist parties out of frustration with national politics and the government’s performance.

The European elections further coincided with national and local elections in Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Hungary, Italy, Ireland, Malta and Romania. The 2024 elections in Belgium were a triple election for the European, federal and regional levels. In this context, European elections were clearly second-order elections. In Bulgaria, the elections coincided with early national elections (the sixth in two years). Thus, European issues were subsumed by overall political instability and infighting, polarizing discourse and a record-low voter turnout.

Populists in government

Populists in government have had varying success in the 2024 European elections. While the FdL in Italy managed to maintain its dominance, including within the governing coalition, the Finns Party saw a sharp drop in support due to its participation in government. While Fidesz maintained its grip on power, it was challenged by a new opposition party, losing two seats in the EP.

In Italy, all the parties in the centre-right governing coalition (FdI, FI, Lega) improved their results compared to the 2022 general elections, thus enjoying a “honeymoon” period of the government elected two years before, reflecting a consolidation of the approval of the Meloni government at the domestic level. Meloni was heavily involved in the European campaign, enabling her party to benefit from her relatively intact popularity as the head of government since September 2022. In Croatia, the right-wing populist DP was already in the position of kingmaker after coming third in the national parliamentary elections in April 2024 and becoming part of the governing coalition. In the EP elections, the DP maintained its support, thus reaffirming its leverage in domestic and European politics.

Elsewhere, populists in government lost ground. In Hungary, despite Fidesz’s victory in the election, a new challenger, Tisza, posed significant challenges, attracting former Fidesz party member Péter Magyar and gaining seven seats in the EP, while Fidesz lost two. Although Fidesz came in first in the EP elections with 44.82% of the votes, the result was considered the party’s worst performance in an EP election. In Finland, the Finns Party paid for its participation in the government and fell back sharply, losing 6 points compared to 2019. The elections revealed voters’ deep distrust towards the government, in which the Finns Party had supported significant austerity measures and cuts to public spending through its leader and finance minister, Riikka Purra. In Sweden, the 2024 European Parliament election was the first election in which the Sweden Democrats participated while having formal influence over the government. The party performed the worst in mobilizing voters in the week leading up to the election, and its support for the centre-right government could possibly explain such an electoral setback.

Political discontent as a driver of populist voting

In countries where populists were in the opposition, these parties benefited from political discontent with national governments dealing with the aftermath of the pandemic, the energy and high inflation crisis, and the many political and economic ramifications of the war in Ukraine.

In Spain, Vox’s electoral campaign was essentially framed as a referendum against Sánchez. In France, both the RN and LFI sought to capitalize on political discontent by making the election a referendum for or against Emmanuel Macron and the government. In Belgium, populist radical parties, both left and right, positioned themselves as political outsiders and presented themselves as the alternative vote to an unpopular federal government. In Cyprus, ELAM strongly campaigned against corruption, entering the political scene as the new political force that would hold traditional parties accountable. In Portugal, Chega’s leader, André Ventura, nominated himself as ‘the real leader of the opposition’. In Germany, after the initial rally-round-the-flag effect following Russia’s fresh attack on Ukraine, the government’s popularity began to decline as a result of high inflation and worries about (energy) security, resulting in a protest vote in favour of populist actors such as the AfD and BSW.

Similarly, in Greece, there was a strong anti-government protest vote, with the key message of the election being political discontent and a general feeling of economic malaise. In Poland, PiS (now in opposition) criticized the government’s opposing measures to stop illegal migration adopted by the previous PiS government. In Romania, AUR has criticized the government and mainstream parties for being subservient to the EU and betraying national interests. In an interview for a Russian newspaper, the leader of the more radical SOS party declared that Romania is essentially a ‘colony within the EU.’

Populist competition

Another factor of varying populist performances was changes in the populist political scene across Europe and new patterns of competition between populists. The recent wave of populism has seen new parties challenge the more established players (Ivaldi, 2023). Such divisions began to appear in countries such as Austria and France in the late 1990s, and more recently, populist competition has been observed in a number of European countries but in different configurations.

While countries such as the Netherlands, Germany, France, Bulgaria and Italy have a variety of populist actors distributed across the political spectrum, there has also been an increasing fragmentation of the populist right in a number of countries in recent years, with two or three of those parties competing with one another for votes, possibly affecting the balance of forces within that party family.

Such a split of the populist right is illustrated in Spain, which has seen the emergence of a new populist radical-right party, Se Acabó La Fiesta (SALF), competing with Vox, which partly accounts for the latter’s loss of support in the 2024 EP elections when compared with the 2023 general elections. In the Netherlands, there has been an increase in parties competing for the populist vote, forcing these parties to profile themselves not only vis-à-vis mainstream parties but also each other. In Poland, the PiS lost 12 points and 8 seats in five years, suffering from competition from Confederation (Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość), which established itself at the heart of the Polish right. In Hungary, Orbán’s party is facing competition from the far-right Our Homeland Movement (MHM). In Romania, AUR is competing for votes with the splinter party SOS. France now has two electorally relevant populist radical-right parties competing with one another, namely, Marine Le Pen’s RN and Éric Zemmour’s Reconquête! In Germany, the AfD is also facing competition on its left flank from the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) on similar anti-immigration policies. In Denmark, the recently formed Denmark’s Democrats compete directly with the Danish People’s Party. As one final example, in Italy, there has been a clear shift in the balance of power between the Lega and FdI, with Meloni’s party taking over the right-wing bloc.

While populist competition essentially concerns the populist right, Ireland provides an interesting case of populist competition to the left of the political spectrum. As the Irish chapter shows, Aontú was in a position to soak up some of Sinn Féin’s collapsing coalition, and it did so by calling more clearly for controls on immigration and by opposing the EU migration pact.

Political profile and candidates

Other factors of variations in populist party performances in the 2024 European elections may be found in the political profile of those parties and lead candidates, as well as in specific campaign events that may have dampened or increased support for those parties.

While some of those parties have taken a path towards normalization, others have maintained a more radical ideology and discourse that may alienate moderate voters. In France, while Le Pen’s RN has been continuing its strategy of “de-demonization” in order to achieve governmental credibility and detoxify its far-right reputation, Zemmour’s Reconquête has come closer to the old extreme right. In Bulgaria, GERB has been moderating its populist appeal, while Vazrazhdane has bet on increasing polarization and extreme right-wing and populist rhetoric. In Ireland, Sinn Féin has transitioned to become a more credible party of government, taking more mainstream positions on a number of issues. In Italy, despite their historical roots in the neo-fascist milieu, Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia have successfully achieved their transformation into a party of government, taking over Forza Italia’s role as the dominant party within the right-wing bloc. As discussed earlier, other parties, such as the Dutch PVV and the Sweden Democrats, have recently undergone a modernization process to increase their coalition potential and increasingly win over the moderate electorate.

In countries like Spain and Finland, on the other hand, the campaign of the 2024 European elections was dominated by public concerns over the rise of the far right in Europe and its possible impact on future alliances in the European Parliament. In Finland, in particular, people’s fear of the rising far right in Europe was a salient theme in campaign debates, which may have contributed to diminished electoral support for the Finns Party.

As clearly illustrated in the country chapters, the choice of lead candidates in the 2024 European elections somewhat reflected such variation in the political pedigree of populist parties. In Denmark, for example, the DF nominated hardliner and former MEP Morten Messerschmidt despite his being still under investigation for fraud in the so-called MELD and FELD case concerning the misuse of EU funds. In Germany, the controversies surrounding the party’s ‘re-migration’ project and Maximilian Krah’s statements about the SS clearly outraged some voters. In Italy, the Lega’s campaign was further stirred by the controversial candidacy of General Vannacci, known for his homophobic, racist and sexist comments. In Portugal, Chega’s lead candidate, António Tânger Corrêa, was strongly criticized for endorsing conspiracy theories such as the ‘great replacement’ and for his using of antisemitic tropes, like accusing the Mossad of forewarning American Jews of terrorist attacks on 9/11. In Finland, the most successful Finns Party candidate, Sebastian Tynkkynen, represented the provocative and radical faction of the party. Another example of strong populist rhetoric and style is found in Romania, where former AUR leader and now a member of SOS Romania, Diana Șoșoacă, is taking her populist rhetoric to new extremes by using tough homophobic, ultra-nationalist, xenophobic and anti-European messages.

Finally, we should mention specific events that may have altered the course of the 2024 elections. One such example is the failed assassination attempt on Prime Minister Robert Fico of SMER, which took place in mid-May 2024, shocking the country and impacting the campaign and elections both directly and indirectly, as both SMER and SNS blamed the opposition and independent media for the attempt, claiming it resulted from a polarized political environment allegedly created by them.

At times, political scandals punctuated the 2024 EP election campaign. In Sweden, the election campaign took a new turn when, about a month prior to the election, it was revealed that the SD’s communications department was hosting a so-called troll factory in which anonymous social media accounts were spreading disinformation and derogatory portrayals of other politicians.

Populist parties and groups in the European Parliament

The 2024 European elections have delivered a new European Parliament whose centre of gravity has clearly shifted to the right and where the presence of populist actors has increased.

The mainstream forces of the European Parliament – the EPP, S&D, and Renew – have maintained a majority with just over 55% of the seats in the new parliament. The conservative right united within the EPP and reaffirmed its dominance within the European institutions, both in the EP and the Council, with 11 seats compared to only 4 for the left and 5 for Renew. Despite the economic crisis, the European left was unable to establish itself as an alternative force during the election. Finally, the Greens and Renew’s liberals emerged as the big losers of the June 2024 elections, with 53 and 77 seats, respectively, a sharp decline compared to 2019 (70 and 98 seats, respectively) (see Table 3).

Table 3. Political groups in the European Parliament as of July 2024

| Political groups | Number of seats | Share of seats (%) |

| EPP–Group of the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats) | 188 | 26.11 |

| S&D–Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament | 136 | 18.89 |

| PfE–Patriots for Europe | 84 | 11.67 |

| ECR–European Conservatives and Reformists Group | 78 | 10.83 |

| Renew Europe–Renew Europe Group | 77 | 10.69 |

| Greens/EFA–Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance | 53 | 7.36 |

| The Left–The Left group in the European Parliament–GUE/NGL | 46 | 6.39 |

| ESN–Europe of Sovereign Nations | 25 | 3.47 |

| NA–Non-attached Members | 33 | 4.58 |

Following the elections, the centre of gravity of the new parliament shifted to the right. In addition to the strong performances of conservative parties, the European election results confirmed the anticipated rise of populist and Eurosceptic right-wing parties.

However, these parties remain divided in the European Parliament, where they are currently distributed across three different groups – namely, the ECR (78 seats), PfE (49), and ESN (25), which have replaced the two previous right-wing populist groups, i.e., ECR and Identity and Democracy. Some populist parties are also found among the Non-attached (NA) (see Table 4).

Table 4. Populist parties by political groups in the 2024 European Parliament

| Country | Type | Party | Seats won | % of vote | EP Group | |

| Bulgaria | Centrist | Ima takav narod | ITN | 1 | 6.20 | ECR |

| Croatia | Extreme Right | Domovinski pokret | DP | 1 | 8.84 | ECR |

| Cyprus | Extreme Right | Ethniko Laiko Metopo | ELAM | 1 | 11.19 | ECR |

| Denmark | Radical Right | Danmarksdemokraterne | DD | 1 | 7.39 | ECR |

| Estonia | Radical Right | Eesti Konservatiivne Rahvaerakond | EKRE | 1 | 14.86 | ECR |

| Finland | Radical Right | Perussuomalaiset/Finns | PS/Finns | 1 | 7.60 | ECR |

| Greece | Radical Right | Elliniki Lysi | EL | 2 | 9.30 | ECR |

| Italy | Radical Right | Fratelli d’Italia | FdI | 24 | 28.76 | ECR |

| Luxembourg | Right | Alternativ Demokratesch Reformpartei (Alternative Democratic Reform Party) | ADR | 1 | 11.76 | ECR |

| Poland | Radical Right | Prawo i Sprawiedliwość | PiS | 20 | 36.16 | ECR |

| Romania | Radical Right | Alianța pentru Unirea Românilor | AUR | 6 | 14.95 | ECR |

| Sweden | Radical Right | Sverigedemokraterna | SD | 3 | 13.19 | ECR |

| Bulgaria | Centrist | Graždani za evropejsko razvitie na Bǎlgarija | GERB | 5 | 24.30 | EPP |

| Italy | Right | Forza Italia | FI | 8 | 9.58 | EPP |

| Netherlands | Centrist | BoerBurgerBeweging | BBB | 2 | 5.40 | EPP |

| Slovenia | Radical Right | Slovenska demokratska stranka | SDS | 4 | 30.65 | EPP |

| Bulgaria | Extreme Right | Vazrazhdane | Vazrazhdane | 3 | 14.40 | ESN |

| Czech Republic | Radical Right | Svoboda a přímá demokracie | SPD | 1 | 5.73 | ESN |

| France | Radical Right | Reconquête! | REC | 5 | 5.46 | ESN |

| Germany | Radical Right | Alternative für Deutschland | AfD | 15 | 15.89 | ESN |

| Hungary | Extreme Right | Mi Hazánk Mozgalom | MHM | 1 | 6.75 | ESN |

| Lithuania | Extreme Right | Tautos ir teisingumo sąjunga (The People and Justice Union) | TTS | 1 | 5.45 | ESN |

| Poland | Extreme Right | Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość | Konf | 3 | 3,19 | ESN |

| Slovakia | Extreme Right | Hnutie Republika | Hnutie Republika | 2 | 12.53 | ESN |

| Germany | Left | Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht | BSW | 6 | 6.17 | NA |

| Greece | Radical Right | Dimokratikó Patriotikó Kínima | NIKI | 1 | 4.37 | NA |

| Greece | Left | Plefsi Eleftherias | PE | 1 | 3.40 | NA |

| Greece | Left | Kommounistiko Komma Elladas | KKE | 2 | 9.30 | NA |

| Poland | Extreme Right | Nowa Nadzieja | Nowa Nadzieja | 2 | 2.79 | NA |

| Poland | Extreme Right | Ruch Narodowy | Ruch Narodowy | 1 | 2.57 | NA |

| Romania | Radical Right | S.O.S. România | SOS RO | 2 | 5.04 | NA |

| Slovakia | Left | SMER – sociálna demokracia | SMER-SD | 5 | 24.77 | NA |

| Spain | Radical Right | Se Acabó La Fiesta | SALF | 3 | 4.59 | NA |

| Austria | Radical Right | Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs | FPÖ | 6 | 25.36 | PfE |

| Belgium | Radical Right | Vlaams Belang | VB | 3 | 22.94 | PfE |

| Czech Republic | Centrist | Akce nespokojených občanů | ANO 2011 | 7 | 26.14 | PfE |

| Czech Republic | Radical Right | Přísaha a Motoristé | Přísaha a Motoristé | 2 | 10.26 | PfE |

| Denmark | Radical Right | Dansk Folkeparti | DF | 1 | 6.37 | PfE |

| France | Radical Right | Rassemblement national | RN | 30 | 31.47 | PfE |

| Greece | Radical Right | Foni Logikis | FL | 1 | 3.04 | PfE |

| Hungary | Radical Right | Fidesz-Magyar Polgári Szövetség | Fidesz | 11 | 44.69 | PfE |

| Italy | Radical Right | Lega | Lega | 8 | 8.98 | PfE |

| Latvia | Radical Right | Latvija pirmajā vietā | LPV | 1 | 6.23 | PfE |

| Netherlands | Radical Right | Partij voor de Vrijheid | PVV | 6 | 16.97 | PfE |

| Portugal | Radical Right | Chega | Chega | 2 | 9.79 | PfE |

| Spain | Radical Right | Vox | Vox | 6 | 9.63 | PfE |

| Bulgaria | Centrist | Prodalzhavame Promjanata-Democratichna Bulgaria | PP-BD | 2 | 14.45 | Renew(PP)EPP(DB) |

| Belgium | Left | Parti du Travail de Belgique-Partij van de arbeid | PTB–PVDA | 2 | 11.76 | The Left |

| Denmark | Left | Enhedslisten – De Rød-Grønne | Enhl., Ø | 1 | 7.04 | The Left |

| France | Left | La France Insoumise | LFI | 9 | 9.87 | The Left |

| Germany | Left | Die Linke | Die Linke | 3 | 2.74 | The Left |

| Greece | Left | Synaspismós Rizospastikís Aristerás | SYRIZA | 4 | 14.92 | The Left |

| Ireland | Left | Sinn Féin | SF | 2 | 11.14 | The Left |

| Italy | Centrist | Movimento 5 Stelle | M5S | 8 | 9.98 | The Left |

| Spain | Left | Podemos | Podemos | 2 | 3.28 | The Left |

| Sweden | Left | Vänsterpartiet | V | 2 | 11.04 | The Left |

Such a reconfiguration of populist groups in the EP reflects a wide array of factors, from national and geopolitical issues to party strategies and political profiles and mutual populist exclusion. The case of Hungarian Fidesz illustrates such complexity. Despite one of the most significant victories across the EU, Orbán’s party faced the challenge of allying with others on the European scene. Initially, Orbán strived to join Meloni’s ECR but ultimately rejected this option to avoid coalescing with the anti-Hungarian AUR in Romania. Additionally, there was a cleavage on the Russia-Ukraine War with Meloni and Jarosław Kaczyński but also smaller members of the ECR from Finland, Latvia and Lithuania, holding diametrically opposed views to Orbán’s. After weeks of negotiations, Orbán succeeded in forming a new coalition based on the former Identity and Democracy group, initially with the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) and the Czech ANO, which was ultimately led by the French National Rally (RN). Although the new Patriots for Europe (PfE) group is the third-largest faction in the European Parliament, it could not secure any significant positions, and thus, Fidesz’s political isolation continues.

Along with the new PfE and previous ECR groups, other right-wing populist parties have found political shelter in the newly formed Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) group. These are essentially extreme right-wing parties such as Our Homeland in Hungary, Reconquête! in France, Hnutie Republika in Slovakia, the Bulgarian Vazrazhdane and Czech SPD. The German AfD leads the group following its expulsion from the former Identity and Democracy faction in the EP in the lead-up to the European elections in May 2024, which was the result of the controversial statements made by the AfD’s lead candidate Maximilian Krah about members of the Nazi SS. The ESN currently has 25 members in the EP.

With a few notable exceptions, such as Fico’s SMER in Slovakia and the German BSW, parties of the populist left are all found in the Left group in the European Parliament. The Left currently has 46 seats, which represents a slight increase on its previous share of 37 seats in the outgoing parliament. After talks of creating a new group with the German BSW, the Italian M5S has joined the European Left, which, as the country analysis has shown, is consistent with the ideological and strategic move to the left by the party in Italian politics.

Finally, somewhat reflecting the diversity in their ideological profile, centrist populist parties are scattered across different groups. The Czech ANO has joined the new populist radical-right PfE along with Orbán’s Fidesz in Hungary and Le Pen’s RN in France. Other centrist populists, such as the Dutch BBB and GERB in Bulgaria, are found in the right-wing conservative EPP, while the Bulgarian ITN has joined Meloni’s ECR. ANO’s decision to leave the liberal Renew group and join the PfE alongside Fidesz and FPÖ poses a curious example. Since the PfE has been excluded from the allocation of posts in the EP committees and subject to cordon sanitaire by the EP majority, ANO is likely to have much less leverage in the new European Parliament.

The impact of populism on EU politics