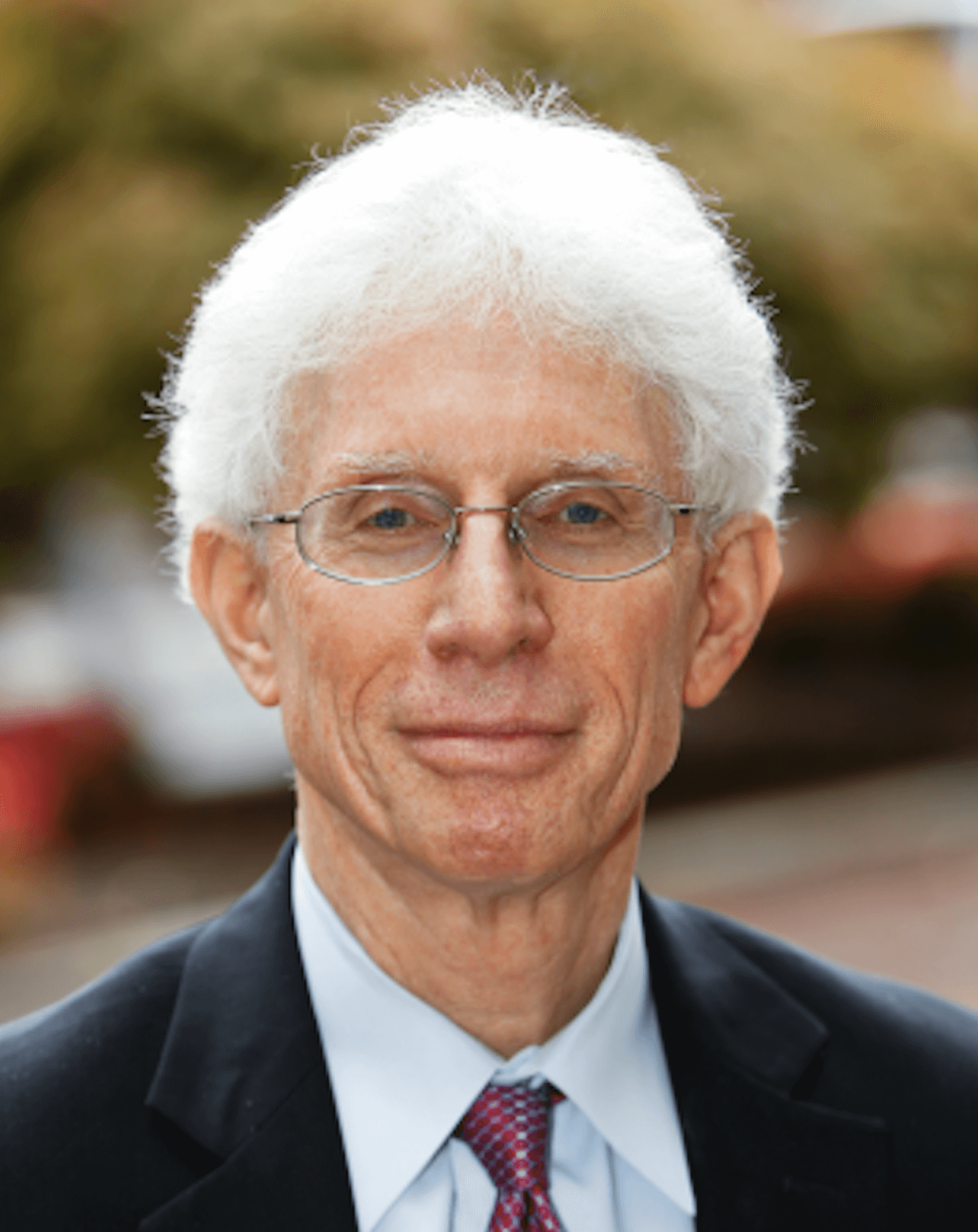

In an exclusive ECPS interview, Professor Kenneth Roth—former Executive Director of Human Rights Watch and now at Princeton—warns that Israel is cynically using charges of antisemitism to shield what he calls genocide and mass atrocities in Gaza. “Netanyahu and his supporters are not defending Jews worldwide,” Professor Roth stresses. “They are sacrificing them—cheapening the very concept of antisemitism just when it is most needed.” Drawing on three decades of human rights leadership, Professor Roth situates Israel’s narrative strategy within a broader authoritarian playbook: populist leaders tilt elections, capture institutions, and scapegoat minorities while silencing dissent. His central warning is stark: criticism of Israel is not antisemitism, and blurring this line endangers both Palestinians and Jews worldwide.

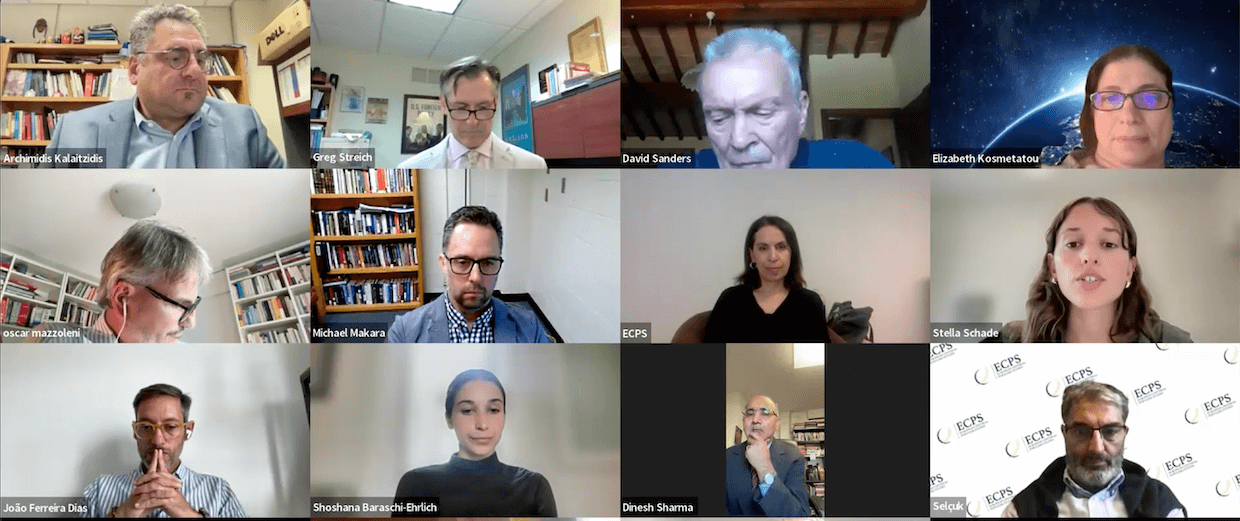

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

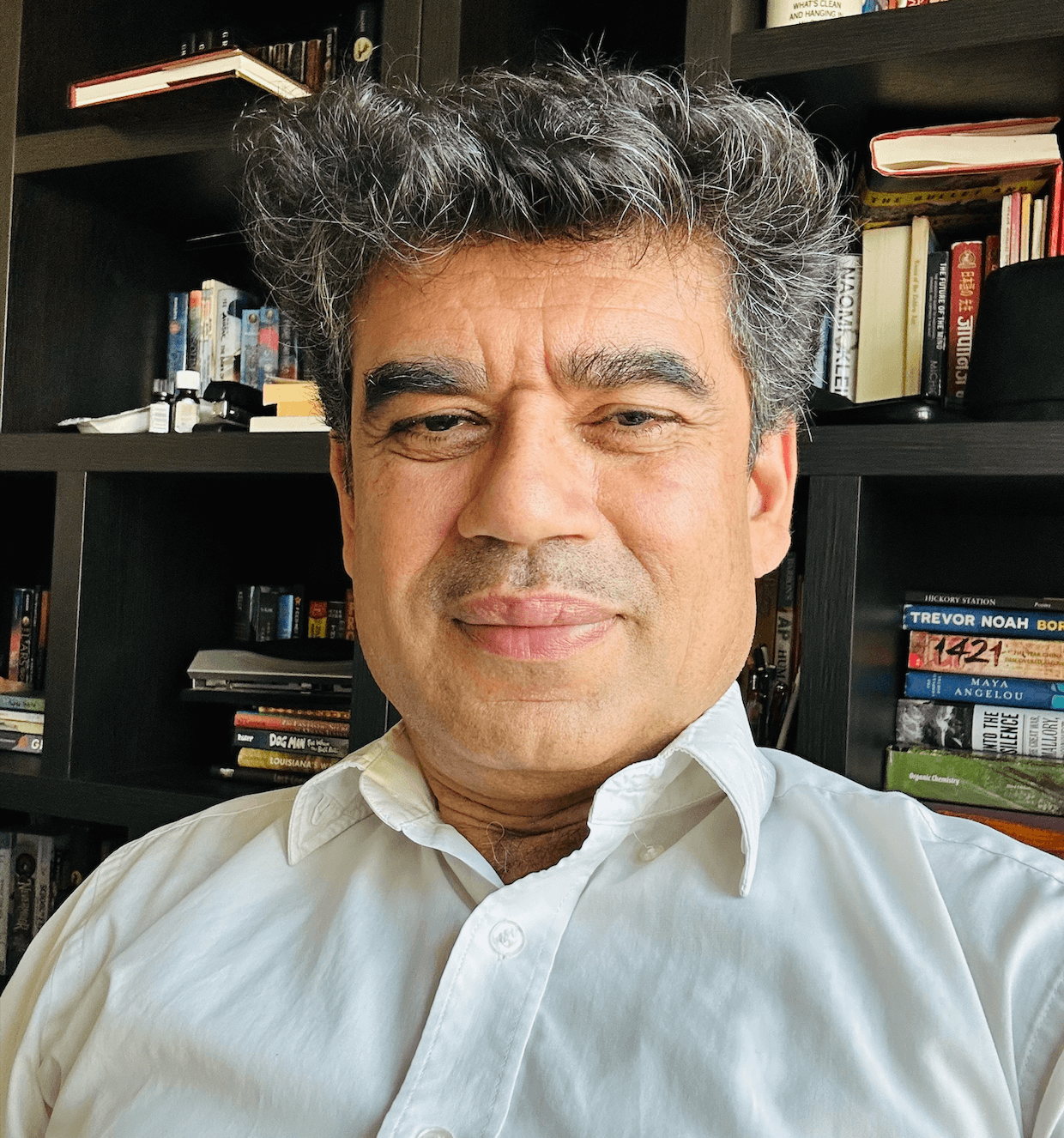

In this exclusive ECPS interview, Professor Kenneth Roth—longtime executive director of Human Rights Watch and now Charles and Marie Robertson Visiting Professor at the Princeton School for Public and International Affairs—warns that the Israeli government is cynically using allegations of antisemitism to silence criticism of what he describes as genocide and mass atrocities in Gaza. “Netanyahu and his supporters are not defending Jews worldwide,” Professor Roth stresses. “They are sacrificing them—cheapening the very concept of antisemitism just when it is most needed.” For him, conflating criticism of Israel with antisemitism not only shields state crimes but also undermines real protections against anti-Jewish hatred.

Professor Roth’s reflections build on more than three decades of global human rights advocacy. At Human Rights Watch, which he directed until August 2022, he oversaw the organization’s expansion into one of the world’s leading rights watchdogs, active in about 100 countries. Earlier, he worked as a federal prosecutor in New York and on the Iran-Contra investigation in Washington. From that vantage, he situates Israel’s narrative strategy within a wider pattern of populist-fueled authoritarianism. Today’s autocrats, Professor Roth argues, “still crave elections but tilt the playing field,”systematically undermining courts, capturing media, restricting NGOs, and intimidating universities. Democracy, he insists, cannot be reduced to ballots alone—it requires freedoms of expression, association, and the rule of law, all under attack.

Even amid authoritarian resurgence, Professor Roth emphasizes the power of coalitions of democratic, rights-respecting states. He recalls decisive breakthroughs such as the treaty banning landmines and the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court (ICC)—both achieved despite superpower opposition. More recent successes, from UN oversight of the Saudi-led bombing campaign in Yemen to European-Turkish pressure curbing Russian strikes in Syria, show that principled middle-power alliances still matter. NGOs, too, must remain unwaveringly consistent: “Our work doesn’t distinguish between perceived friend and foe—we apply the same standards to everybody,” Professor Roth explains. That consistency, he argues, sustains credibility and strengthens the politics of shaming.

The interview traverses urgent contemporary debates: Trump’s embrace of authoritarian leaders, his sanctions on the ICC, and his “flood-the-zone” tactic of overwhelming institutions with constant shocks. Professor Roth dissects the dangers of scapegoating minorities, the misuse of Holocaust memory to excuse present atrocities, and the precedent of blurring law enforcement with war in extrajudicial killings. At every step, he insists that human rights must not be selectively applied or subordinated to cynical populist narratives.

Taken together, Professor Roth’s insights offer both a sobering indictment and a pragmatic roadmap: exposing the authoritarian logic that links populism, repression, and impunity, while affirming that principled coalitions and civil society can still defend rights. Above all, his warning is clear: criticism of Israel is not antisemitism—and protecting the integrity of that distinction is essential for Jews worldwide, Palestinians under siege, and the universality of human rights.

Here is the transcript of our interview with Professor Kenneth Roth, lightly edited for clarity and readability.

Autocrats Still Crave Elections but Tilt the Playing Field

Thank you so much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: In your recent writings, you stress the fragility of checks against authoritarian drift and note how today’s rulers “raise the cost” for defenders by targeting courts, media, and NGOs. What, in your view, makes this current wave of populist-fueled democratic backsliding distinct from earlier authoritarian surges, particularly in the subtler tactics of regulation, funding, and legal harassment?

Professor Kenneth Roth: I’m not sure it’s completely unique, but clearly autocrats are learning from each other. The current wave is characterized foremost by what you might call electoral authoritarianism. That is, autocratic leaders who still want the legitimacy of an election but use the steps of the autocrat’s handbook to undercut checks and balances on their authority and to tilt the electoral playing field in their favor.

It’s pretty straightforward what they do: they target the various potential checks on their authority—courts, lawyers, journalists, academics, civil society—and use different techniques to undermine their independence. With the media, for example, outlets may be owned by large corporate conglomerates vulnerable to government pressure. We’re seeing that in the United States right now. It could also take the form of regulations that make it harder for civil society to secure funding, particularly from abroad. Sometimes it’s direct attacks, such as withholding funding, which we’re now seeing Trump do with universities.

These are variations on a theme, but the aim is always the same: to stymie and weaken the elements that sustain democracy. Because democracy is not just about elections. It is about the freedoms of expression, association, and assembly, as well as the rule of law that holds leaders accountable to the law and to the rights it embodies. And these autocrats are intent on undercutting those checks. It’s pretty clear.

Coalitions of Democracies Can Overcome Superpower Opposition

You have argued that coalitions of mid-sized states—beyond the West—can sometimes defend human rights more effectively than major powers, urging leverage toward countries like India, Brazil, South Africa, Japan, and even China. Two decades on, do you still see these “plural centers of pressure” as the backbone of rights defense, or has today’s fractured multilateralism, intensified authoritarian entrenchment, and the rise of populist geopolitics blunted that strategy—and what would an updated map of leverage look like?

Professor Kenneth Roth: I wouldn’t say that coalitions are better than the major powers, but that they can serve as substitutes when the major powers stand in opposition. At this stage, when the US government has essentially stopped promoting human rights, I don’t think we should just throw in the cards and give up. There have been many cases in the past where coalitions of governments have compensated for the absence—or even the opposition—of the US government, not to mention the Soviet or Russian government, or the Chinese government. I describe this in my book Riding Wrongs, where repeatedly, coalitions of democratic, rights-respecting governments, when banded together, have had the moral authority to overcome superpower opposition.

That’s what happened with the treaty to ban landmines. All the major powers opposed it, yet a group of about 60 governments—a coalition that Human Rights Watch and our colleagues helped to build—overcame that opposition. We ended up sharing the Nobel Peace Prize for that effort. Something very similar occurred with the creation of the International Criminal Court (ICC). You may recall the Clinton administration was adamantly opposed to a court that could even theoretically prosecute an American. That was not its idea of justice. Yet in the final vote in Rome in 1998, the US lost overwhelmingly—120 to 7—marking a decisive victory for the rule of law.

More recently, as I describe in my book, despite a lack of any assistance, if not outright opposition, from Washington, a group of governments led by the Netherlands secured oversight from the UN Human Rights Council of the Saudi-led coalition’s bombing in Yemen—making a huge difference in terms of saving civilian lives. Another coalition, involving Germany, France, and Turkey, pressured Putin in March 2020 to stop bombing the three million civilians in Idlib province in Syria, the last area at the time held by the armed opposition.

These are just a few among many examples showing how coalitions of governments can effectively defend human rights—not only without Washington, but often despite its opposition.

NGOs Must Be Principled—Apply the Same Standards to All

Since major powers like the US, Russia, and China routinely instrumentalize human rights for geopolitical ends, how should NGOs and the broader rights community rethink their strategy—balancing naming-and-shaming with ally-seeking—while avoiding the slide from principled engagement into complicity in populist or authoritarian projects?

Professor Kenneth Roth: The idea that governments instrumentalize human rights is nothing new. This has always happened. If you just go back historically, there was a tendency during the Cold War to highlight the human rights abuses of one’s opponents and neglect the human rights abuses of one’s allies. So, this has always been a problem. I think the role that NGOs should play is to be principled. That is to say, to ensure that our work doesn’t distinguish between perceived friend and foe, but that we apply the same standards to everybody. That enhances the capacity to shame, because people understand that when human rights groups condemn somebody, when we spotlight a government’s abuse, we’re not pursuing some geopolitical strategy. We are pursuing a universal, principled effort.

Now, shaming is never the only thing that human rights groups do. We also enlist influential allies to try to put diplomatic or economic pressure on a target government, and I describe this in my book. These are important supplements to the process of shaming.

The fact that governments are selective in their defense of human rights does undermine their credibility, but doesn’t preclude our ability to enlist them, because frankly, nobody is consistent. So, we try to enlist allies where we can, push them to be more principled. But we don’t have a rule that you’ve got to be perfect before we enlist you, because then we’d enlist nobody. We’ve got to be a bit more pragmatic than that and try to maximize pressure on a target government from any credible source that we can find.

Trump Isn’t Blurring Lines—He’s Embracing Authoritarianism

Trump’s open admiration for autocrats such as Putin, Bolsonaro, Erdogan, and Netanyahu blurs distinctions between democracy and authoritarianism, while also resonating with a global populist style that treats rights as obstacles to “the people’s will.” To what extent has Trump shifted the normative boundaries of US foreign policy on human rights, and what does this mean for the wider contest between populism and rights-based democracy?

Professor Kenneth Roth: First, I would not say that Trump is blurring the distinction between democracy and authoritarianism. He’s simply embracing authoritarianism. I don’t think anybody believes that because Trump embraces Putin, suddenly Putin is a democrat. That’s absurd. Trump, as an aspiring autocrat, admires leaders who have managed to secure autocratic power for themselves. That’s what he does. And we obviously have to push back against that.

This is a bad period for US foreign policy, but it’s not the first time we’ve seen something like this. Think back to the George W. Bush administration, when the so-called global war on terrorism became an excuse not only to support abusive governments but also to engage in severe human rights abuses by the US government itself—systematic torture and the use of Guantanamo for endless detention without trial.

We have seen this flouting, this unwillingness to abide by human rights standards emanating from Washington before. Our job in the human rights movement is to spotlight complicity in human rights violations, or responsibility for them, when the government behaves inconsistently, and to push for it to be even slightly less inconsistent. Fortunately, the American people—and I think this is also true globally—want a more consistent human rights policy.

That’s why spotlighting inconsistency is valuable, because it forces leaders like Trump to pay a political price. When he is seen as aiding and abetting genocide in Gaza, we can already see the effect on US public opinion. People are turning against Israel; they are upset with the unconditional US support for Israel. We’ve seen Trump react to that somewhat already—not sufficiently—but this effort is worthwhile. Ultimately, this is how we can pressure Trump to do the one thing that would end the genocide: suspend or condition massive US arms sales and military aid to Israel until the genocide stops.

Rulings Mean Little Without Government Backing

You’ve argued that “democracy” without rights is easily gamed by “despots masquerading as democrats.” After the ICJ advisory opinion(s) and an emboldened ICC, can international courts still constrain leaders amid intensified lawfare and sanctions against judges/prosecutors? What insulating reforms (treaty, funding, travel protections) matter most?

Professor Kenneth Roth: There’s a lot in that question, so let me try to dissect it a bit. First, when despots masquerade as democrats, it means they still hold periodic elections, but they tilt the playing field so much that the elections become meaningless. This can be a dangerous endeavor. Take Viktor Orban in Hungary or Erdogan in Turkey: they are classic autocrats who still hold competitive elections but with very severe limitations. Orban today faces a serious challenger in Peter Magyar, who is charismatic and has united the opposition. It may not work for him. Erdogan went so far as to lock up his main opponent because, according to the polls, that opponent was going to win. His party had already won the major mayoral elections in Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, and elsewhere. The more an autocrat moves toward a zombie election—that is, one with zero credibility—the more they lose the very legitimacy they seek. That’s what Daniel Ortega did in Nicaragua, Museveni in Uganda, Putin in Russia, and Lukashenko in Belarus. They hold electoral charades, but no one is fooled, and they simply become dictators.

I don’t view international courts as particularly effective against these kinds of autocratic attacks on democracy. The courts are more useful in addressing mass atrocities. For example, with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC) entering the fray in Gaza, and with the ICC charging Putin and four generals for Ukraine, these are important efforts. They may someday lead to actual trials in The Hague. Even short of that, they are incredibly stigmatizing. They mean that these leaders cannot travel to the 125 ICC member states without risking arrest.

Of course, an ICJ judgment or an ICC arrest warrant does not self-execute. They don’t automatically constrain leaders because these Hague-based courts don’t have police forces; they depend on governments for enforcement. That’s always a problem. So, we need governments that claim to uphold the rule of law to act consistently with these rulings. Take the ICJ advisory opinion on the illegality of Israel’s endless occupation: governments should now ensure they do nothing to support that occupation. On the ICC, Trump outrageously imposed sanctions on the ICC prosecutor, the two deputies, and six judges. It’s important, particularly for the European Union, to use its so-called blocking statute to neutralize those sanctions so that judges and prosecutors can continue to access their bank funds and operate normally.

I would also encourage the prosecutor to examine whether this constitutes obstruction of justice—a violation of Article 70 of the Rome Statute—which I think it clearly does. One option would be to actually charge Trump for this blatant interference with an independent institution of justice. So, there is plenty that still can be done, but we shouldn’t deceive ourselves into thinking that international courts, simply by issuing rulings, automatically change the world. They need the backing of governments.

Being a Drug Trafficker Doesn’t Make You a Combatant

In critiquing Trump’s extrajudicial killings of Venezuelan traffickers, you warned of the drift from policing to “war” rules in law enforcement. If such precedents take hold—turning metaphorical wars on drugs or terror into literal grounds for lethal force—what global spillovers do you foresee, and what bright-line doctrines should civil society insist on to prevent their entrenchment?

Professor Kenneth Roth: First, let me explain the two sets of rules that govern the use of lethal force. In war, you’re allowed to shoot combatants on the other side, and unless they’re surrendering or injured and thus out of combat, you can shoot to kill. There is no duty to detain them. By contrast, in law enforcement situations, it’s almost the opposite: lethal force can be used only as a last resort to meet an imminent threat of death or serious physical injury. It is an extremely limited use of lethal force; otherwise, the duty is to arrest and prosecute.

Now, Trump has ignored that distinction. He has declared Venezuelan suspected drug traffickers—people we have no real knowledge about—and has, in three separate incidents, blown up boats and killed those on board, simply on the claim that they were traffickers. But being a drug trafficker does not make you a combatant. There is no war, no armed conflict here. If you believe Trump’s account, these people were committing crimes and should have been arrested and prosecuted. The US Coast Guard is fully capable of interdicting these boats, detaining the suspects, bringing them to Miami or elsewhere, and prosecuting them.

Trump is disregarding the strict law enforcement rules on lethal force by declaring this a “war,” and therefore claiming the right to shoot to kill. That is an incredibly dangerous precedent, because he could label anyone a combatant or terrorist—terms he wrongly uses interchangeably. But even terrorists are criminals who must be prosecuted, not summarily executed. We have to be very careful here, because what’s to stop him from declaring a war on civil society or a war on the political opposition and then justifying killings on that basis?

This is a very dangerous precedent. Even though drug traffickers are unpopular, it is essential to start with the principle: even if they are suspected traffickers, they should not simply be blown up. They have the right to be detained, charged, and prosecuted if the administration’s claims are true. That is why it is crucial not to let metaphorical wars on drugs or terrorism be transformed into literal wars that substitute the narrow rules on lethal force in law enforcement with the much more permissive rules governing armed conflict—which this clearly is not.

How Populist Autocrats Weaponize Minorities to Mask Their Failures

You’ve tracked how strongman admiration and majoritarian claims corrode protections for minorities and migrants. Has Trump’s second term normalized an executive theory of unfettered discretion that will outlast him in US foreign policy—and how should allies signal costs early to deter that stickiness?

Professor Kenneth Roth: As you’re suggesting in your question, populist autocrats frequently rally support by demonizing some unpopular minority in their country. It could be immigrants, LGBT people, or Muslims—it varies from country to country. It is very important to push back against this. Typically, they resort to such tactics to divert attention from their lack of a political program that could actually address the economic and political needs of their base. Usually, their base is the ethnic majority working class.

When you see leaders demonizing immigrants or LGBT people, you can almost be certain there is no serious program to help the working class. Trump is a perfect example. He loves to demonize immigrants. Then he puts forward a massive economic plan that cuts taxes for his cronies while eliminating healthcare for many who need it. This doesn’t help the working class—it decimates it.

It’s important to expose this sleight of hand—the use of scapegoating unpopular minorities to distract from harmful economic policies. So, what’s the best way to push back? First and foremost, by defending the rights of these minorities. We cannot pretend that an attack on one unpopular group will stop there. In fact, I often view attacks on LGBT people as the canary in the coal mine for broader assaults on civil society. Those almost always follow.

We need to recognize the path populist autocrats are taking and nip it in the bud. We cannot ignore the early stages just because the victims are unpopular. This is a well-trodden path, and it must be stopped at the outset.

Countering Trump’s Flood-the-Zone Strategy

You’ve described Trump’s “flood-the-zone” strategy—overwhelming opponents and institutions with constant shocks—as a hallmark of autocratic playbooks. From the resistance you’ve observed, what lessons proved transferable to other democracies under stress, and which were context-specific wins?

Professor Kenneth Roth: I’m not sure that Trump’s flood-the-zone strategy is typical. It’s pretty unique to Trump. It especially characterized his first few months in this second term, when there was one outrage after another, day after day, and people were so busy responding to yesterday’s crisis that they didn’t know where to start with today’s. Now it has slowed down a bit, but he continues to use the tactic—finding some new provocation every few days to divert attention from what he had already done.

The key for the targets of these efforts is not to let themselves be overwhelmed but to band together and coordinate their defense. We didn’t always see that in the United States. For example, certain universities, like Columbia, cut deals with the Trump administration, while others have since taken a more principled stand and joined forces. Some big law firms also cut deals, while others chose to fight back in court—and are now winning. Trump has also turned his threats toward civil society, but here too, many large progressive private foundations have banded together, issuing a joint statement declaring that they will not be divided and will fight back collectively.

That kind of collective response—the refusal to let Trump pick off opponents one at a time, as he has done with certain media outlets—is essential. When a powerful government can target one victim at a time, the victims usually lose. But when it faces a coordinated defense, the chances of success rise significantly.

When Sovereignty Becomes Impunity

Trump’s sanctions on the ICC—aimed at blocking investigations of Israel and US officials—highlight how powerful states can obstruct accountability through jurisdictional caveats and intimidation. What does this precedent mean for the enforceability of international criminal law, and what enforcement pathways remain viable to safeguard prosecutorial independence?

Professor Kenneth Roth: When you say jurisdictional caveats, I think what you’re referring to is that the Trump administration, like the US government for much of the last 20-plus years, has objected to the International Criminal Court’s so-called territorial jurisdiction. That is, the court can prosecute anybody who commits a crime on the territory of a member state. Going back to the Clinton administration, the US government hated that because it meant that American military personnel could theoretically be prosecuted if they committed a crime on the territory of a member state. That’s why the US government was so outraged, in the first Trump administration, when the ICC opened an investigation into Afghanistan—because there was fear that Bush-era torturers, many of whose worst crimes were committed there, might be subject to prosecution. Now, that turned out to be more of a theoretical concern, but that’s the territorial jurisdiction the US government has always objected to.

Ironically, when that same territorial jurisdiction was used by the ICC to charge Putin for crimes committed in Ukraine, everything changed. Biden called it justified. Lindsey Graham, the leading Republican senator who had always opposed the ICC, suddenly said, “I’ve changed my mind, we support the ICC now.” He even pushed through a unanimous resolution, and the Senate upheld what the ICC had done. That remained the case until that same territorial jurisdiction was used to charge Netanyahu for crimes committed in Gaza, in Palestine—a member state. Then suddenly it was back to outrage. The US position has been utterly unprincipled. Fortunately, nobody else accepts that. As I mentioned, the US lost its efforts to block territorial jurisdiction in Rome at the outset by a vote of 120 to 7. This is a losing proposition, and the key is for the 125 member states to reaffirm their support for territorial jurisdiction.

Of course, a state should be able to say, in a time of crisis, if our courts are not working—if we can’t prosecute people who commit crimes on our territory ourselves—we should be able to delegate that power to the ICC. That should be an inherent aspect of sovereignty. For the US to say, “Oh, well, because we’re American, we can commit a crime on your territory with impunity”—that’s crazy. If I, as an American citizen, were to go to Brussels and murder somebody, is it an affront to American sovereignty if Belgium prosecutes me? Obviously not. So why would it be an affront to American sovereignty if, under extreme circumstances, Belgium delegates that prosecutorial power to the ICC? This is normal. But the US insists on American exceptionalism when it comes to the rule of law. Nobody buys that, and governments should find ways to push back.

The Vanity Lever: Using Trump’s Ego to Pressure for Human Rights

You’ve suggested Trump’s transactional ego—the “vanity lever”—can sometimes be used to pressure him on rights. How realistic is it to constrain authoritarian choices through vanity appeals, and where should we draw the ethical line between pragmatism and entrenching cynical politics?

Professor Kenneth Roth: What I’ve written about is that if you approach Trump frontally and say, support human rights, he’ll probably look at you and say, what are those? This is not a guy who is going to openly support human rights. But, as I describe in my book, the process of shaming always has to look at the target and figure out what they care about. In Trump’s case, what he cares about is his self-declared reputation as a master negotiator. In his book The Art of the Deal, he defines what he thinks is great about himself.

That gives us some leverage. For one, he wants a Nobel Peace Prize. Fine—you’re not going to get a Nobel Peace Prize by endorsing the mass ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from Gaza. You’ll get the Nobel Peace Prize by actually securing a just peace, including recognition of a Palestinian state. Another effective strategy is to spotlight how Putin in Ukraine and Netanyahu in Gaza are actually bamboozling Trump. They’re manipulating him, they’re playing games with this supposed master negotiator, and Trump looks naive.

He hates that. This is a guy with a fragile ego who doesn’t like criticism. If people are laughing at him, ridicule is horrible when you’re an autocrat. So, I think that provides an opportunity. We’re already seeing some movement by Trump in Ukraine. He has not yet imposed the so-called severe consequences he promised if Putin continues to obstruct ceasefire negotiations, but his rhetoric has become somewhat tougher. In the case of Gaza, we also see Trump distancing himself in certain ways from Netanyahu—for example, rejecting Netanyahu’s false claim that there is no starvation in Gaza, criticizing him for attacking the Hamas negotiators in Qatar, and twice imposing temporary ceasefires.

So, there is some distance there. I think we just need to keep pushing, with the aim of getting Trump to do the right thing for the wrong reasons. I don’t think that’s cynical—it’s simply pragmatic. If that’s what it takes to stop mass atrocities, I’ll do it.

When Ethnic Cleansing Becomes a Defense to Genocide

You’ve argued that Israel’s actions in Gaza meet the Genocide Convention through killings and life-destroying conditions, even alongside ethnic-cleansing motives. How do you answer critics who say genocidal intent is unproven, and what evidence most strongly supports its inference under current ICJ standards?

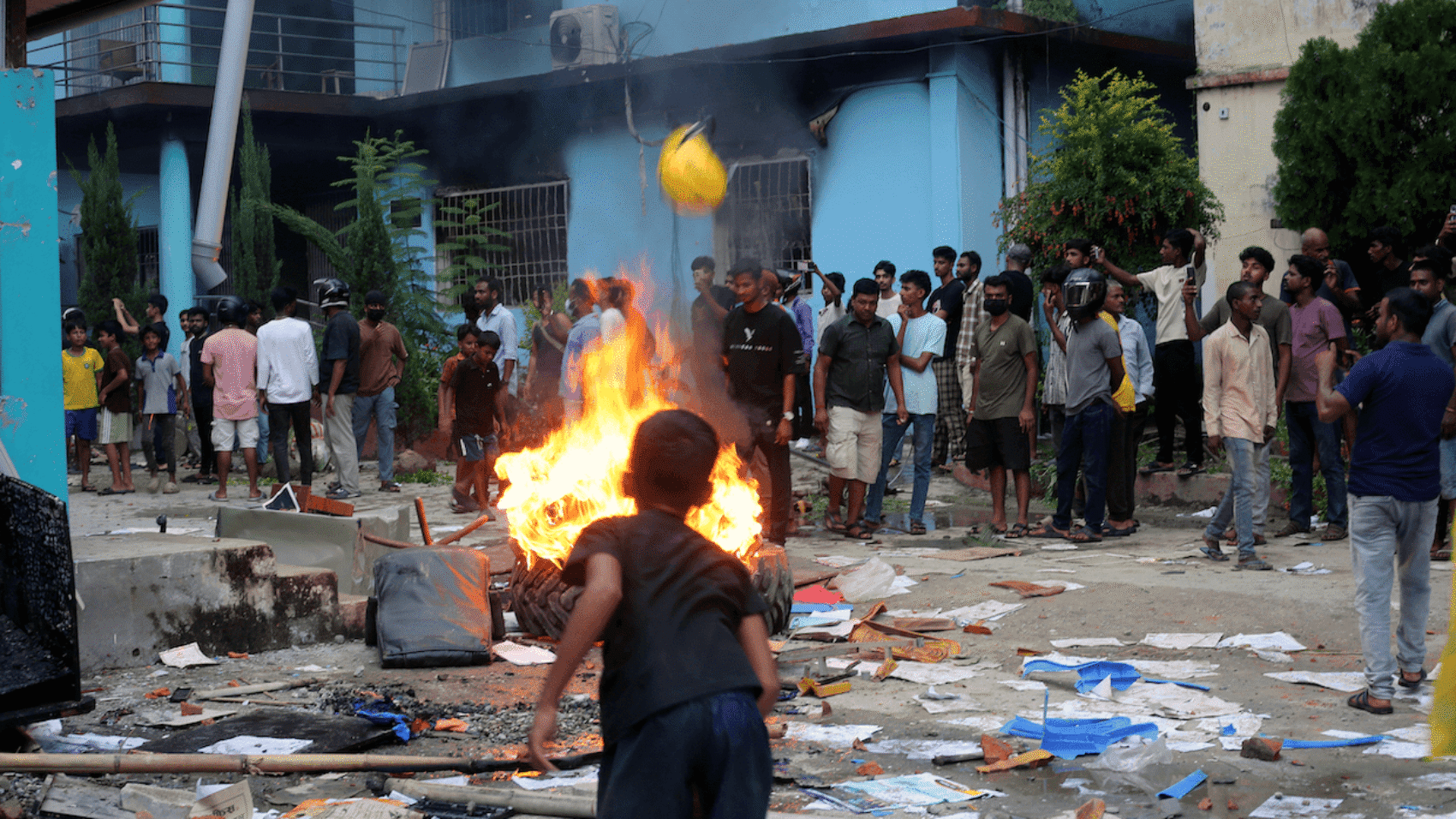

Professor Kenneth Roth: If you look at either the extent of the killing or the imposition of conditions of life designed to destroy, in whole or in part, an ethnic or national group, what’s going on in Gaza is clearly genocide. At this point, the clearest example is the imposition of mass starvation, mass deprivation, and the wholesale destruction—today of Gaza City, but overall of all Gaza. The aim, quite clearly, is to make Gaza unlivable so that it becomes “humane” to then force everybody out into Egypt. The ultimate aim here is ethnic cleansing, a supposed solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by getting rid of the Palestinians—first in Gaza, and then later in the occupied West Bank. That’s clearly what’s going on.

The only real challenge here—you mentioned the International Court of Justice standards—is that the court ruled in the Croatia v. Serbia case more than a decade ago that if you are going to infer genocidal intent from conduct, it has to be the only possible inference. I think that’s a wrong standard. They are going to have to re-examine it, because in effect what they have said is that the motive of ethnic cleansing becomes a defense to genocide, which makes no sense. To prove genocidal intent, the standard should be absolute: are you clearly demonstrating genocidal intent? The fact that there may be a mixed motive—that there may be genocide in the service of something else—is often how genocide takes place.

So, I do think the ICJ will have to revisit its standards. It will have an opportunity in the Gambia v. Myanmar case concerning the Rohingya, where something very similar occurred. The Myanmar army killed, say, 10,000 Rohingya in order to force 730,000 to flee into Bangladesh. That was genocide as a means to mass ethnic cleansing. I hope the court uses that case, which will come first, to re-examine its standards, to find that the conduct does permit an inference of genocidal intent. That would then also apply positively to the case of Gaza.

Criticism of Israel Is Not Antisemitism

You’ve warned that equating criticism of Israel with antisemitism both silences accountability and weakens real protections for Jews. What are the dangers of this conflation, and what concrete standards can help distinguish legitimate criticism from antisemitic incitement without suppressing dissent?

Professor Kenneth Roth: That’s an important question. Let me begin by saying that the problem of antisemitism is an acute one today facing Jews around the world, and it has become much more intense since October 7, 2023. So, this is a genuine problem. But what we’ve seen is that Netanyahu, the Israeli government, and some of its supporters are using charges of antisemitism to try to silence criticism of Israel’s genocide and mass atrocities in Gaza.

That’s a very cynical move, because it cheapens a concept that is badly needed. If people come to see claims of antisemitism as just an effort to change the subject and defend Israel’s inexcusable conduct in Gaza, they will become cynical about antisemitism at the very moment we need it to remain a viable concept. In effect, what Netanyahu and his supporters are doing is sacrificing Jews around the world for the benefit of the Israeli government. They’re basically saying: we’re going to throw Jews worldwide under the bus. Who cares if you face antisemitism? Who cares if we’re cheapening the concept? All we care about is defending the Israeli government. That’s a horrible thing to do—but that, in essence, is what the Netanyahu government is doing.

Now, are there standards on antisemitism? Yes. The standard that legitimizes this cynical approach is the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism. The way it’s been interpreted has lent itself to saying that criticism of Israel, or efforts to demonize Israel, are somehow antisemitic.

There are two far superior definitions of antisemitism: the Jerusalem Declaration and the Nexus Document. The reason they are superior is that they make explicit that mere criticism of Israeli misconduct is not antisemitic. They define antisemitism in positive terms similarly, but they also include negative examples to make clear that antisemitism should never be weaponized to shield Israeli misconduct.

So, if the concern is truly antisemitism, people should adopt the Jerusalem Declaration or the Nexus Document. But if the concern is simply defending Israel while throwing Jews around the world to their fate, then go with the IHRA definition.

“Never Again” Means Never Again for All

You argue that Israel’s invocation of “never again” and its Holocaust halo have been weaponized to justify present atrocities. How has this complicated recognition of genocidal conduct, and how can we honor historical victimhood without letting it serve as a blank check—while restoring legal clarity around proportionality and civilian protection?

Professor Kenneth Roth: As you suggest, the Israeli government, much like the Rwandan government, cites the Holocaust for Jews and the Rwandan genocide to suggest that the current government is somehow above it all. The logic is: how could the victims of genocide, in turn, commit mass atrocities? Obviously, that’s illogical, but they use the argument implicitly to try to defend the indefensible.

For me, “never again” doesn’t mean never again except for Israel, never again except for Rwanda. It means never again for anybody. Part of the advantage the Israeli government has is that when people think about genocide, they tend to focus on the Holocaust or the Rwandan genocide, where the aim, after a certain point, was to kill every Jew or every Tutsi that could be found.

But if you read the Genocide Convention—the treaty that defines genocide and that many governments have ratified—genocide can be aimed at destroying a group in whole, as in the Holocaust or Rwanda, or in part. This is where the Holocaust and Rwandan examples can mislead, because it is also genocide if you target part of a group, either for killing or through conditions of life that bring about their partial destruction. That is what defines Gaza today. The Israeli government is not trying to kill every single Palestinian. But it is trying to kill enough Palestinians and deprive them with enough severity that they are forced to flee into Egypt. Genocide with an intent to destroy a group in part is what’s really going on here. The Holocaust leads us astray because that’s not what it was about. So, we need to read the Genocide Convention as written and recognize that the Holocaust alone does not define genocide. There are other forms—such as the one playing out in Gaza today.

Past Genocides Do Not Justify Present Atrocities

And lastly, you’ve drawn parallels between Kagame’s Rwanda and Netanyahu’s Israel in weaponizing past victimhood to justify present crimes. How can the human rights community dismantle such narratives without denying past genocides, and which accountability tools—aid conditionality, arms suspensions, or regional pressure—have proven most effective against such impunity politics?

Professor Kenneth Roth: As I mentioned, both Netanyahu and Kagame play on past genocide to divert attention from their current mass atrocities—Netanyahu in Gaza, and Kagame through both his repression at home and, most acutely, his invasion of Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo through his own forces as well as the proxy M23 rebel group.

The goal of the human rights community is obviously not to deny the Holocaust or the Rwandan genocide. These are facts, these are horrific episodes in human history. But the point is to say: “Yes, they happened, but they don’t excuse present abuses.” So, we have to carefully document what’s happening in Congo and in Gaza and press for real pressure to stop it.

That pressure can and should include economic measures. Sadly, the European Union—while many of its members are recognizing a Palestinian state—has yet to suspend Israel’s trade benefits, despite vows from Commission President von der Leyen to do so soon. In eastern Congo, back in 2012, a similar Rwandan invasion via the M23 was stopped in its tracks when the US and British governments told Kagame they would cut off aid unless he withdrew. Within days, the M23 crumbled. Today, that isn’t happening. Trump cut a deal allowing Rwanda to stay and exploit the minerals.

So, we need to look at what has worked in the past, namely intense economic pressure. I would like to see the International Criminal Court (ICC)—which has already acted in part in Gaza—do much more and also extend its action to eastern Congo. It has done so in the past, but not with respect to this current invasion. Plenty of steps remain available to help rein in Kagame and Netanyahu and to stop their misuse of past atrocities as an excuse for committing new ones today.