DOWNLOAD PDF

Please cite as:

Yilmaz, Ihsan; Mamouri, Ali; Morieson, Nicholas & Omer, Muhammad. (2025). “The Transnational Diffusion of Digital Authoritarianism: From Moscow and Beijing to Ankara.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). May 12, 2025. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0098

This report examines how Turkey has become a paradigmatic case of digital authoritarian convergence through the mechanisms of learning, emulation, and cooperative interdependence. Drawing on Chinese and Russian models—and facilitated by Western and Chinese tech companies—Turkey has adopted sophisticated digital control strategies across legal, surveillance, and information domains. The study identifies how strategic partnerships, infrastructure agreements (e.g., Huawei’s 5G and smart city projects), and shared authoritarian logics have enabled the Erdoğan regime to suppress dissent and reshape the digital public sphere. Through legal reforms, deep packet inspection (DPI) technologies, and coordinated digital propaganda, Turkey exemplifies how authoritarian digital governance diffuses globally. The findings highlight an urgent need for international accountability, cyber norms, and ethical tech governance to contain the expanding influence of digital repression.

By Ihsan Yilmaz, Ali Mamouri*, Nicholas Morieson & Muhammad Omer**

Executive Summary

This research explores the diffusion of digital authoritarian practices in Turkey as a prominent example of the Muslim world, focusing on the three mechanisms of learning, emulation, and cooperative interdependence, covering four main domains: Legal frameworks, Internet censorship, urban surveillance, and Strategic Digital Information Operations (SDIOs). The study covers both internal and external diffusion based on a wide range of sources. These include domestic precedents, examples from authoritarian regimes like China and Russia, and the role of Western companies in spreading digital authoritarian practices.

The study had several findings. The key findings are detailed below:

Learning: Turkey, like other regional countries that experienced public unrest, has learned from previous experience in order to impose power and control on people using different digital capabilities. Countries like China and Russia played significant roles in this learning process across the region, including in Turkey. The research highlights the importance of both internal learning from past protest movements and external influences from state and non-state actors.

Emulation: Authoritarian regimes in Turkey and across the Muslim world have emulated China and Russia’s internet governance models in all four aforementioned domains. The Turkish government has developed its own surveillance and censorship techniques, influenced by the experiences of authoritarian states and bolstered by training and technology transfers from China and Russia, and certain western companies.

Cooperative interdependence: Turkey’s economic challenges have led it to forge closer ties with China, particularly through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This cooperation often comes with financial incentives, promoting the adoption of China’s digital governance practices, including urban surveillance systems and censorship technologies.

Role of private technology companies: Western companies have played a significant role in facilitating the spread of digital authoritarianism, often operating independently of their governments’ policies. Companies like Sandvine and NSO Group have provided tools that support the Turkish government’s digital control strategies, contributing to a complex landscape of censorship and surveillance.

Diffusion of SDIOs: The diffusion process of digital authoritarian practice is not limited to importing and using digital technologies. It also includes the spreading of legal frameworks to restrict digital freedom and also running Strategic Digital Information Operations (SDIOs), including state propaganda and conspiracy theories that China and Russia had a significant role in.

Based on these findings, the study proposes several recommendations to counteract the spread of digital authoritarian practices:

– Strengthening international cyber norms and regulations to define and regulate digital governance, particularly in countries with strong ties to the West.

– Enhancing support for digital rights and privacy protections by advocating for comprehensive laws and supporting civil society organizations in Turkey.

– Encouraging responsible corporate behavior among technology firms to ensure compliance with human rights standards.

– Fostering regional and global cooperation on digital freedom to counter digital authoritarianism through joint initiatives and technical assistance.

– Leveraging economic incentives to promote ethical technology use and partnerships with human rights-aligned providers.

– Using strategic diplomatic channels to encourage Turkey to adopt responsible surveillance practices and align with global digital governance norms.

The research illustrates the dynamics of digital authoritarianism in Turkey, revealing a complex interplay of emulation, learning, and economic incentives that facilitate the spread of censorship and surveillance practices. The findings underscore the need for international cooperation and proactive measures to safeguard digital freedoms in an increasingly authoritarian digital landscape.

Introduction

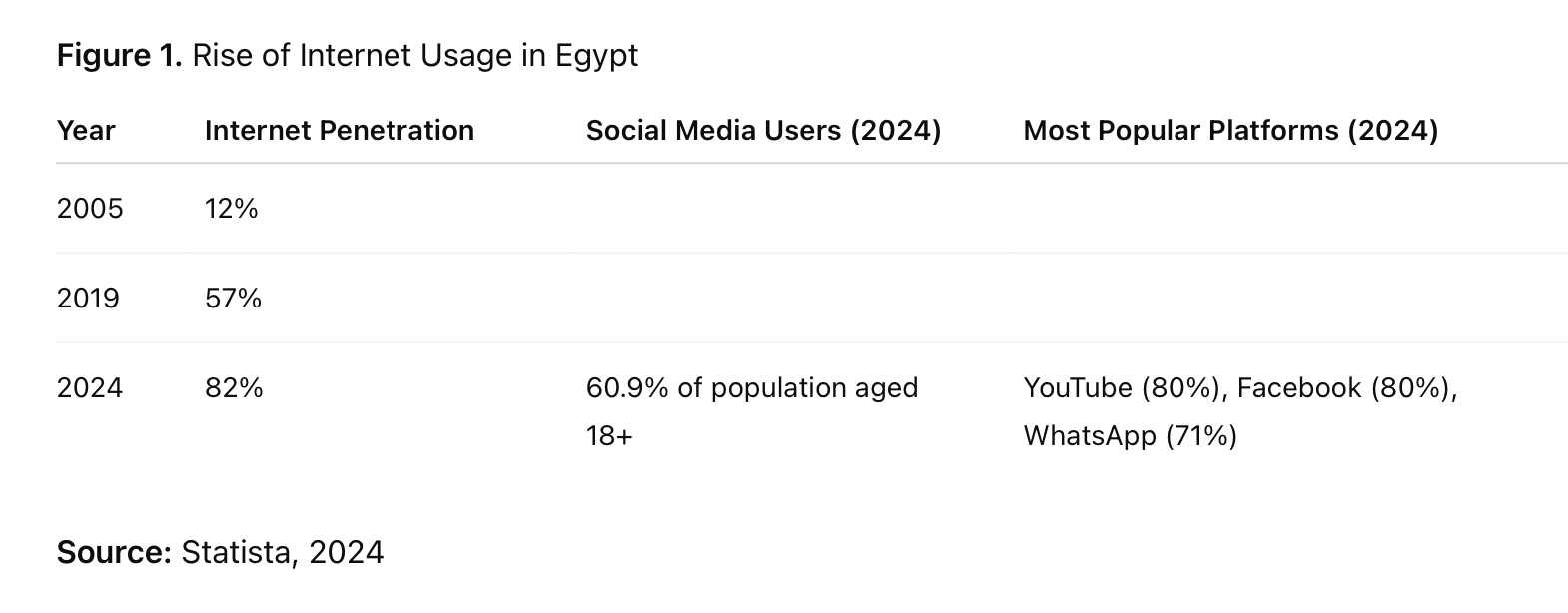

Research suggests that a significant number of countries in the Muslim world, specifically those in the Middle East, are often characterized by authoritarian governance (Durac & Cavatorta, 2022; Yenigun, 2021; Stepan et al., 2018; Yilmaz, 2021; 2025). The rise of the internet and social media during the late 2000s provided immense capacities to civil society and individual activists in the Muslim world. This development burst into political action during the late 2000s and the early 2010s in the instances of the Gezi protests in Turkey and other examples in the region, including the Green Movement in Iran and the Arab Spring protests across the Arab world (Iosifidis & Wheeler, 2015; Demirhan, 2014; Lynch, 2011; Gheytanchi, 2016).

The fact that the protesters in all these cases have extensively used the internet and associated technologies (e.g., social media, digital messaging, and navigation) has led many observers to declare the latter as ‘liberation technology’ due to their role in facilitating anti-government movements across non-democratic countries (Diamond & Plattner, 2012; Ziccardi, 2012). Advocates of the internet as a liberation tool have also pointed to enhanced social capacity to mobilize and organize through the spread of dramatic videos and images, instigating attitudinal change, and countering government monopoly over the production and dissemination of information (Breuer, 2012; Ruijgrok, 2017). These qualities have been seen as giving the internet an equalizing power between the state and society. In the early 2000s, when the Internet and social media were spreading across the developing world, authoritarian governments were generally unable to control the digital sphere; they lacked the technical expertise and the digital infrastructure to curb the internet. So, they typically relied on completely shutting it down (Cattle, 2015; Gunitsky, 2020).

However, authoritarian regimes gradually learned how to use the digital space for empowering their control on the society and have even started using it for transnational repression and sharp power (Yilmaz, 2025, Yilmaz et al., 2024; Yilmaz, Akbarzadeh & Bashirov 2023; Yilmaz, Morieson & Shakil, 2025; Yilmaz & Shakil, 2024). Scholars such as Sunstein (2009) and Negroponte (1996) have warned against the capacity of the internet to fragment the public sphere into separate echo chambers and thus fundamentally impede ‘deliberative democracy,’ which is supposed to be based on debates of ideas and exchange of views.

Furthermore, the breakthroughs in deep learning, neural network, and machine learning, together with the widespread use of the internet, have accelerated the growth of artificial intelligence (AI), providing more capability to authoritarian regimes to impose control on people. In a Pew poll, almost half of the respondents believed that the ‘use of [modern] technology will mostly weaken core aspects of democracy and democratic representation in the next decade’ (Anderson & Rainie, 2020). This pessimism is driven by an unprecedented degree of surveillance and digital control brought forward by digital technologies, undermining central notions of freedom, individuality, autonomy, and rationality at the center of deliberative democracy (Radavoi, 2019; Stone et al., 2016; Bostrom, 2014; Helbing et al., 2019; Damnjanović, 2015). Tools of the governments to digitally repress democracy include smart surveillance using facial recognition applications, targeted censorship, disinformation and misinformation campaigns, and cyber-attacks and hacking (Feldstein, 2019).

Research as to how digital technologies such as high-speed internet, social media, AI, and big data affect, enable or disable democracy, human rights, freedom, and electoral process is in its infancy (Gardels & Berggruen, 2019; Margetts, 2013; Papacharissi, 2009). Further, most of this scant literature is focused on Western democracies. The existing literature on Muslim-majority countries is mostly focused on traditional social media (Jenzen et al., 2021; Wheeler, 2017; Tusa, 2013). This is despite the fact that extensive digital capabilities, especially AI and big data, offer governments of these countries the capabilities to exert control over their citizens, with disastrous outcomes for democracy. Indeed, we may be facing the rise of a new type of authoritarian rule: digital authoritarianism, that is, ‘the use of digital information technology by authoritarian regimes to surveil, repress, and manipulate domestic and foreign populations’ (Polyakova & Meserole, 2019; see also Ahmed et al., 2024; Akbarzadeh et al., 2024; 2025).

With the expansion of the internet in developing countries, authoritarian governments derive a similar benefit from technological leapfrogging with the capacity to selectively implement new surveillance and control mechanisms from the burgeoning supply of market-ready advanced AI and big-data-enabled applications. As one internet pioneer foreshadowed to Pew “by 2030, as much of 75% of the world’s population will be enslaved by AI-based surveillance systems developed in China and exported around the world” (Anderson & Rainie, 2020). Developing countries often experience technological leapfrogging; they shift to advanced technologies directly, skipping the middle, more expensive and less efficient stages because modern technologies, by the time of their implementation within those countries, become more economical and effective than the initial technology. This leapfrogging is demonstrated via the adoption lifecycle of mobile phones to that of landlines. It took less than 17 years, from the early 2000s to 2017, for mobile phones to be extensively adopted in Turkey, from 25% to 96%. (Our World in Data, 2021).

After the crises of the early 2010s, both democratic and authoritarian regimes worldwide started to invest heavily in sophisticated equipment and expertise to monitor, analyze, and ultimately crack down on online and offline dissent (Aziz & Beydoun, 2020; Feldstein, 2021). In addition to curtailing independent speech and activism online, authoritarian regimes have sought to deceive and manipulate digital environments in order to shape their citizens’ views. They have flooded the digital realm with propaganda narratives using trolls, bots, and influencers under their control (Tan, 2020).

More importantly, thanks to authoritarian diffusion, governments in developing countries are learning from and emulating the experiences of their peers of surveillance technologies such as China and Russia. However, there has been limited research on the political mechanisms through which such digital authoritarian practices spread. Against this backdrop, this report examines the mechanisms through which digital authoritarian practices diffuse in Turkey as an example of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East. We ask: What kind of authoritarian practices have the governments enacted in the digital realm? How have these practices diffused across the region? To address these questions systematically, we develop an analytical framework that examines the mechanisms of diffusion of digital authoritarian practices. Our framework identifies three mechanisms of diffusion: emulation, learning, and cooperative interdependence. We focus on four groups of digital authoritarian practices: legal frameworks, Internet censorship, urban surveillance, and Strategic Digital Information Operations (SDIOs). We aim to show how emulation, learning and cooperative interdependence take place in each of these four digital authoritarian practices. In addition to the above, the report will explore the international dimension of this phenomenon, discovering how Western companies, in addition to totalitarian systems like Russia and China, played a role in empowering the Turkish government to claim the digital space.

We first discuss our analytical framework which integrates the scholarship of digital authoritarian practices and authoritarian diffusion, and explain the concepts of learning, emulation, and as prominent diffusion mechanisms. We then move to the empirical section where we first identify convergent outcomes that are comparable between earlier and later adopters and then we will elucidate the mechanisms through which the diffusion process occurred by showing contact points and plausible channels through which decision-makers were able to adopt from one another.

Analytical Framework

To explore the phenomenon of diffusion, we follow best practices laid out in the literature (see Ambrosio, 2010; Ambrosio & Tolstrup, 2019; Bank & Weyland, 2020). We begin by identifying convergent outcomes that are comparable between earlier and later adopters. As part of this, we will also establish feasible connections between the two parties, which may take the form of physical proximity, trade linkages, membership in international organizations, bilateral arrangements, historical ties, cultural similarities, or shared language. Then, we will elucidate the mechanisms through which the diffusion process occurred by identifying contact points and plausible channels through which decision-makers were able to adopt from one another.

We will follow three good practices that have been advised by scholars (e.g., Ambrosio & Tolstrup, 2019; Strang & Soule, 1998; Gilardi, 2010; 2012). First, we adopt a comparative design that involves four middle powers (see Strang & Soule, 1998). There are important similarities and differences among the four cases that make comparison a useful exercise. Second, we provide extensive data to showcase the workings of diffusion mechanisms despite the challenge of working on authoritarian settings. As Ambrosio and Tolstrup (2019: 2752) noted, “the relevant evidence needed can be hard to acquire in authoritarian settings.” It is much more likely to gain access to strong evidence in liberal democratic settings where much of the current diffusion research has accumulated. Our article contributes to the literature on diffusion in authoritarian settings with Turkey as a prominent example. Finally, we provide smoking gun evidence based on several leaked documents to support our assertions.

In the empirical section, we follow the convention (see Ambrosio & Tolstrup, 2019) and start with identifying convergent outcomes among the major political actors in regard to the practices of restrictive legal frameworks, Internet censorship, urban surveillance and SDIOs. This section involves demonstrating the items that have been diffused between earlier and later adopters. Not only is there a substantial amount of similarity between the practices among these political systems, but also, we show a temporal sequence between earlier and later adopters that point at convergence.

We then move on to explain plausible mechanisms of diffusion, following the model provided by Bashirov et al. (2025): Learning, Emulation, and Cooperative Interdependence. It’s important to highlight from the outset that these three mechanisms functioned together in Turkey settings. As was observed in other settings (see Sharman, 2008), it is not feasible to examine the impact of these mechanisms independently. Instead of existing as separate entities or operating in a simple additive manner, these mechanisms are inherently interconnected, and they do overlap. We follow this understanding in our empirical analysis and discuss how each mechanism worked in tandem with other mechanisms.

Types of Digital Authoritarianism

We identified four main domains of digital authoritarianism in general, and examples of them could be found in Turkey’s case as well.

Restrictive Legal Frameworks

The legal framework includes a variety of practices. We identified the following:

1- Laws that mandated internet service providers to establish a system allowing real-time monitoring and recording of traffic on their networks. These legislations mandated internet service providers to establish a system allowing real-time monitoring and recording of traffic on their networks (Privacy International, 2019). Moreover, all censorship laws refer to national security and terrorism as vague criteria to enforce widespread censorship of undesirable content. In Turkey, a Presidential decree (No 671) in 2016 granted the government extensive power to restrict internet access, block websites, and censor media (IHD, 2017). Under the decree, telecommunications companies are required to comply with any government orders within two hours of receiving them. In recent years, the Turkish government also prosecuted thousands of people for criticizing President Erdogan or his government in print or on social media (Freedom House, 2021).

2- Laws that have converged around penalization of online speech, referring to concepts such as national identity, culture, and defamation. It is hard to miss similarities between the laws in Turkey among other regional countries and those enacted in China earlier. In 2013, China’s Supreme People’s Court issued a legal interpretation that expanded the scope of the crime of defamation to include information shared on the internet (Human Rights Watch, 2013). In 2022, the Turkish Parliament passed new legislation that criminalized “disseminating false information,” punishable by one to three years in prison, and increased government control over online news websites. Article 23 of the law was particularly controversial as it stated that “Any person who publicly disseminates untrue information concerning the internal and external security, public order and public health of the country with the sole intention of creating anxiety, fear or panic among the public, and in a manner likely to disturb public peace, shall be sentenced to imprisonment from one year to three years” (Human Rights Watch, 2022). This clearly shows the pattern of diffusion from China and Russia by leaving vague and broad provisions of what constitutes “national security,” “peace” and “order” (Weber, 2021: 170-171; Yilmaz, Caman & Bashirov, 2020; Yilmaz, Shipoli & Demir, 2023; Yilmaz & Shipoli, 2022).

3- Laws that ban or restrict the use of VPNs following China and Russia’s lead. In Turkey, VPNs are legal, but many of their servers and websites are blocked. China banned unauthorized VPN use in 2017 in a new Cybersecurity Law. Russia introduced a similar ban the same year. The Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK), national telecommunications regulatory and inspection authority of Turkey, issued a blocking order targeting 16 Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). These VPNs, including TunnelBear, Proton, and Psiphon, are popular tools used by audiences seeking to access news websites critical of the government.

While entirely banning VPN access remains a challenge, governments can employ Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology to identify and throttle VPN traffic. Countries like Iran, China, and Russia are indulging in such practices. Users in Iran and Turkey, for example, have reported extensive blockage of VPN apps and websites since 2021. Engaging in efforts to access blocked content through a VPN can potentially result in imprisonment (Danao & Venz, 2023). Simon Migliano, research head at Top10VPN.com, acknowledges that blocking VPN websites in Turkey makes it harder to download and sign up for new services. Moreover, individual VPN providers like Hide.me, SecureVPN, and Surfshark confirm technical difficulties for their users in Turkey. Proton, on the other hand, maintains that their services haven’t been completely blocked.

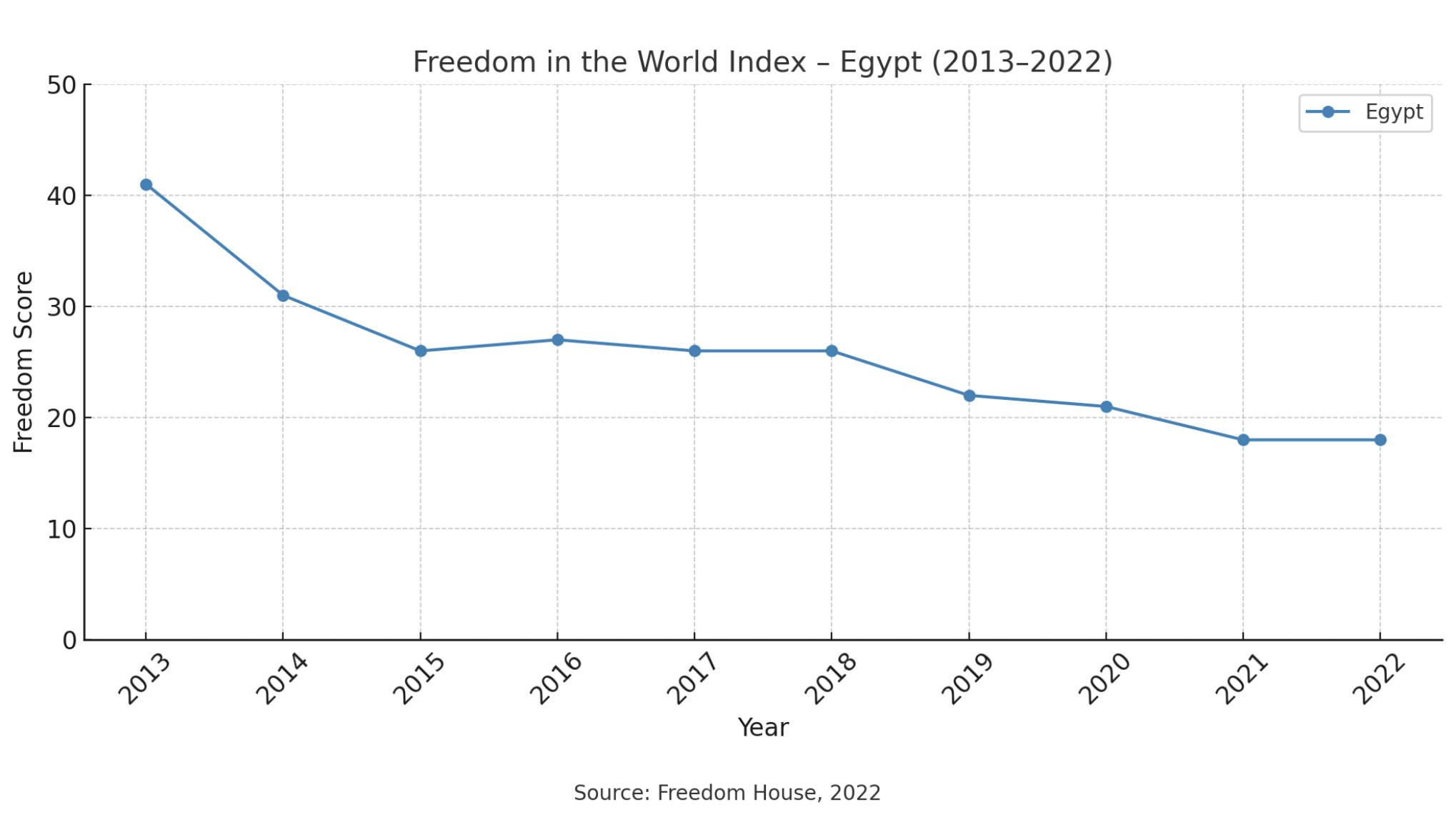

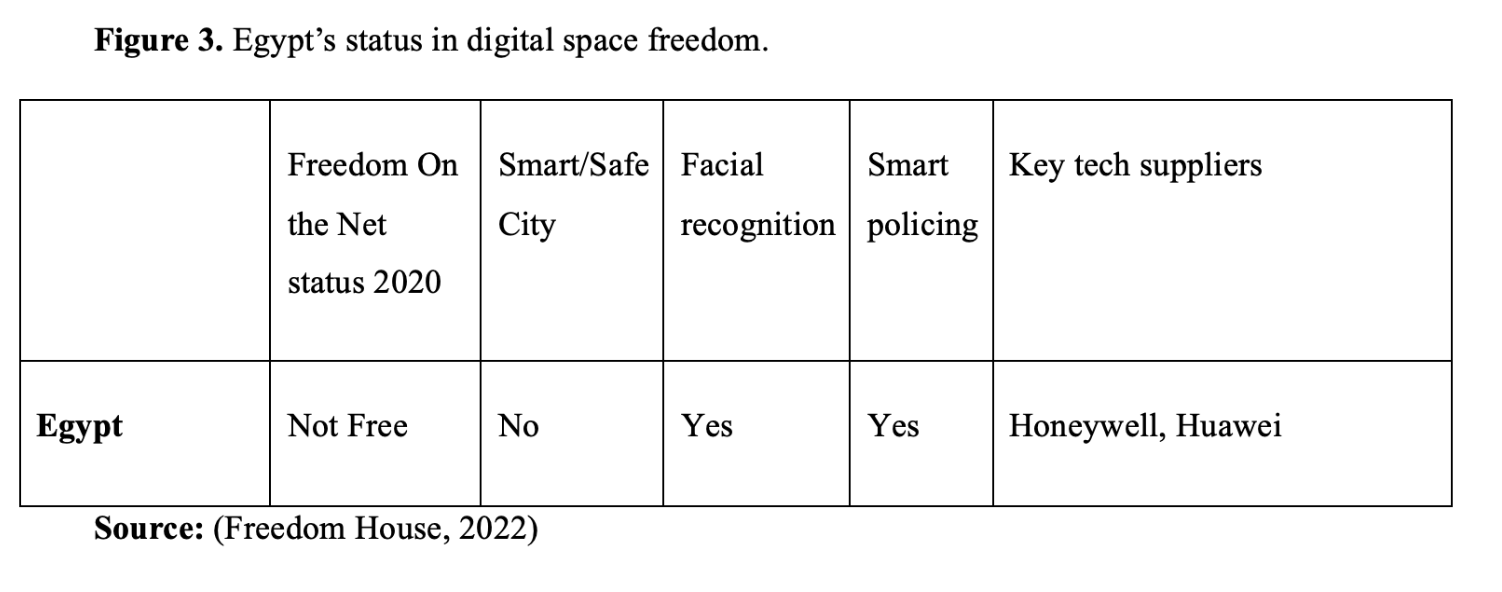

As such, the report “Freedom on the Net 2023” by Freedom House (2023) reflects the aforesaid harsh reality, ranking Turkey as “not free” in terms of internet access and freedom of expression. However, it is worth noting that the Turkish government’s censorship efforts are met with a determined citizenry. Audiences, even young schoolchildren according to Ozturan (2023), have become adept at using VPNs to access banned content. Media outlets themselves sometimes promote VPNs to help their audiences bypass restrictions. Examples abound: VOA Turkish and Deutsche Welle (DW), upon being blocked, directed their audiences towards Psiphon, Proton, and nthLink to access their broadcasts. Diken, a prominent news website, even maintains a dedicated “VPN News” section offering access to censored content dating back to 2014.

4- Laws that tighten control on social media companies. While Western social media platforms remain accessible in Turkey, in recent years the government has introduced similar laws and regulations that increase their grip over the content shared on these platforms. They do so by threatening the social media companies with bandwidth restrictions and outright bans if they fail to comply with the governments’ requests. Moreover, in 2020, the Turkish Parliament passed a new law that mandated tech giants such as Facebook and Twitter (now X) to appoint representatives in Turkey for handling complaints related to the content on their platforms. Companies that decline to assign an official representative have been subject to fines, advertising prohibitions, and bandwidth restrictions that would render their networks unusable due to slow internet speeds. Facebook complied with the law in 2021 and assigned a legal entity in Turkey after refusing to do so the previous year (Bilginsoy, 2021).

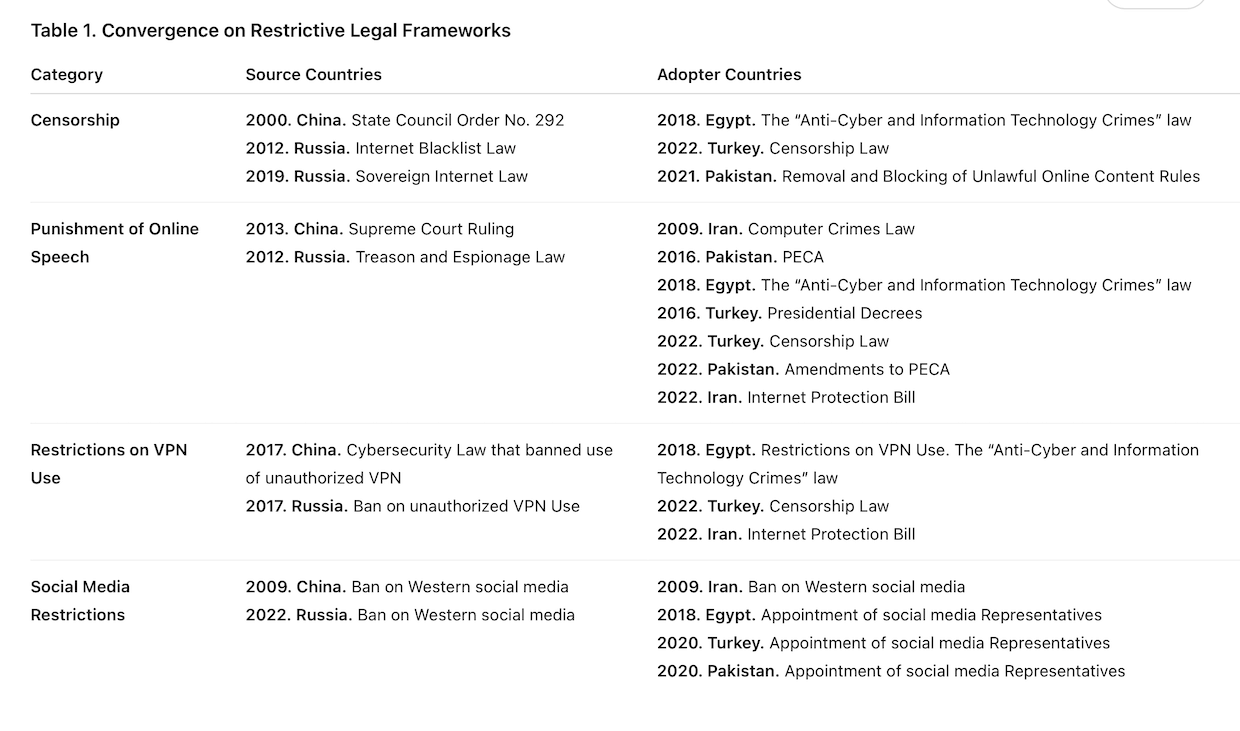

Since the early 2010s, many countries in the region including Turkey have enacted a series of legal reforms that converged around similar concepts and restrictions. As Table 1 shows, these laws follow the Chinese and Russian laws in temporal order. The table makes a comparison with some other countries in the region as well, in order to see Turkey’s position in this field.

Internet Shutdown

All governments in the region have resorted to shutting down the internet as a simple solution over the past 20 years, mostly during the times of mass protests, social unrest or military operations. In Turkey, in 2015, access to Facebook, Twitter and YouTube as well as 166 other websites were blocked when an image of a Turkish prosecutor held at gunpoint was circulated online. The internet was also cut off multiple times during the July 15, 2016 coup attempt, as well as during the Turkish military’s operations in the Southeastern regions of the country. In many instances, the government has used bandwidth throttling to deny its citizens access to the internet. However, internet shutdown is costly as it affects the delivery of essential public and private services and has been dubbed as the Dictator’s Digital Dilemma. Therefore, even when it is practiced, the shutdown is limited to a certain location, mostly a city or a region, and would typically last only few days. According to Access Now (2022), an internet rights organization, no internet shutdown has taken place in Turkey in 2021.

Given the high cost of switching off the internet and thanks to the rise of sophisticated technologies to filter, manipulate and re-direct internet content, censorship has become a more widely used digital authoritarian practice over the last decade. Countries have converged on the use of DPI technology. DPI is “a type of data processing that looks in detail at the contents of the data being sent, and re-routes it accordingly” (Geere, 2012). DPI inspects the data being sent over a network and may take various forms of actions, such as logging the content and alerting, as well as blocking or re-rerouting the traffic. DPI allows comprehensive network analysis. While it can be used for innocuous purposes, such as checking the content for viruses and ensuring the correct supply of content, it can also be used for digital eavesdropping, internet censorship, and even stealing sensitive information (Bendrath & Mueller, 2011).

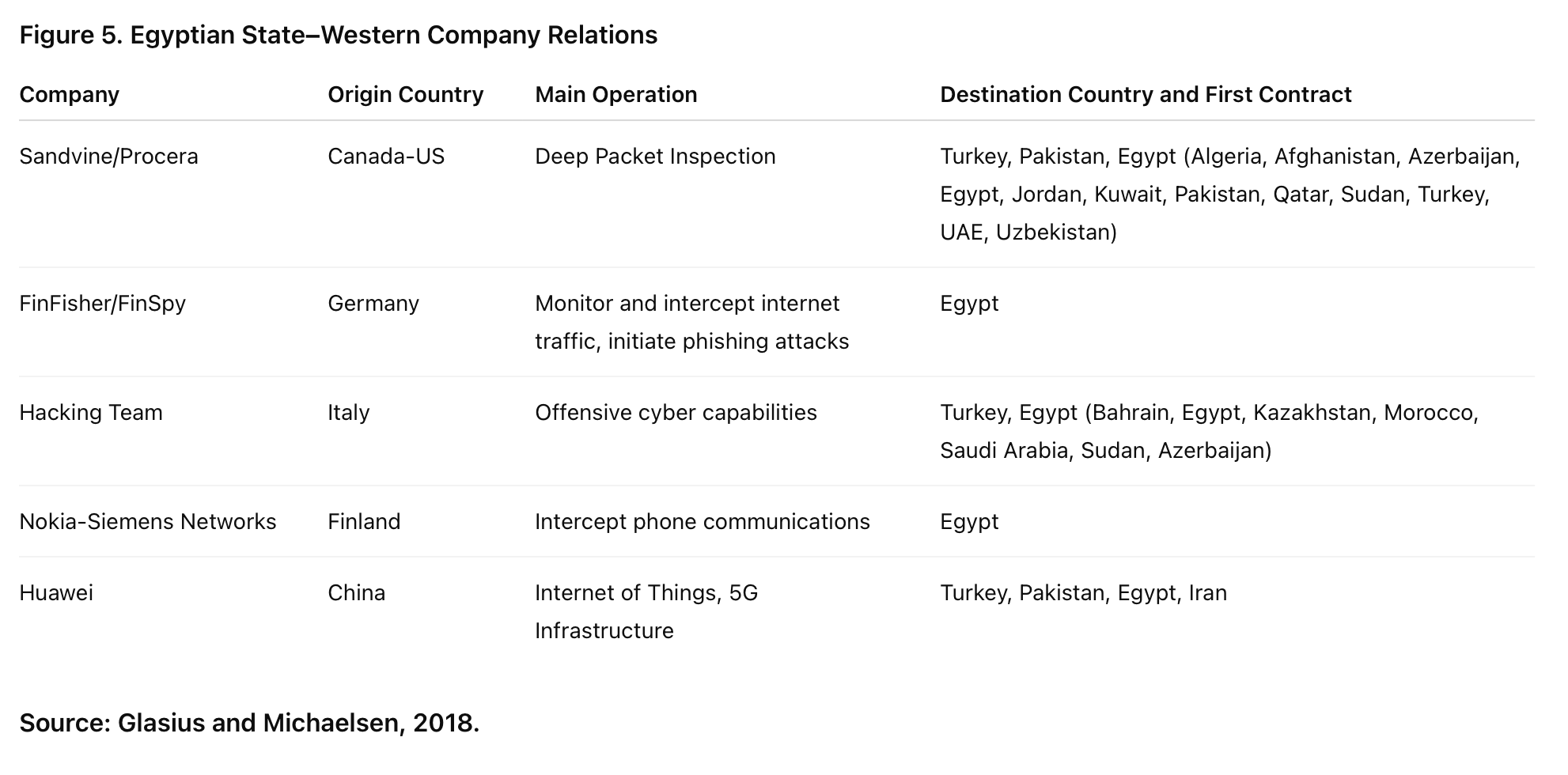

Countries across the Muslim world including Turkey started in the mid-2010s to acquire DPI technology from Western and Chinese companies who have become important sources of diffusion. US-Canadian company Sandvine/Procera has provided DPI surveillance equipment to national networks operating in Turkey (Turk Telekom). This system operates over connections between an internet site and the target user and allows the government to tamper with the data sent through an unencrypted network (HTTP vs. HTTPS). Sandvine and its parent company Francisco Partners emerged at the center of the diffusion of DPI technology in the Middle East. Recent revelations show that the company has played significant role in facilitating the spread of ideas between countries. Through their information campaign, Sandvine contributed to learning by governments. As such, Sandvine and Netsweeper’s prominent engagement in provision of spying technology shows that it is not merely Chinese companies that enable digital authoritarianism. Western companies have been just as active.

Turkey made its first purchase from Sandvine (then Procera) in 2014 after the Gezi protests and corruption investigations rocked the AKP government the previous year. The government later used these devices to block websites, including Wikipedia, and those belonging to unwanted entities, such as independent news outlets and certain opposition groups in later years. The governments in the region including Turkey have gathered widespread spying and phishing capabilities sourced from mostly Western companies. For example, in Turkey, FinFisher used FinSpy in 2017 on a Turkish website disguised as the campaign website for the Turkish opposition movement and enabled the surveillance of political activists and journalists. FinSpy allowed the MIT to locate people, monitor phone calls and chats and mobile phone and computer data (ECCHR, 2023). This could link in with our discussion in emulation more clearly as well regarding private companies being key actors (Marczak et al., 2018).

Urban Surveillance

With the advance of CCTV and AI technology, urban surveillance capabilities have grown exponentially over the past ten years. Dubbed as “safe” or “smart” cities, these urban surveillance projects are “mainly concerned with automating the policing of society using video cameras and other digital technologies to monitor and diagnose “suspicious behavior” (Kynge et al., 2021). The concept of Smart city captures an entire range of ICT capabilities implemented in an urban area. This might start with the simple goal of bringing internet connectivity and providing electronic payment solutions for basic services and evolve to establishing AI-controlled surveillance systems, as we have seen in many Chinese cities (Zeng, 2020). Smart cities deploy a host of ICT—including high-speed communication networks, sensors, and mobile phone apps—to boost mobility and connectivity, supercharge the digital economy, increase energy efficiency, improve the delivery of services, and generally raise the level of their residents’ welfare (Hong, 2022). The “smart” concept generally involves gathering large amounts of data to enhance various city functions. This can include optimizing the use of utilities and other services, reducing traffic congestion and pollution, and ultimately empowering both public authorities and residents.

The rapid development of smart city infrastructures across world has led to controversies as critics argued that the surveillance technology enables pervasive collection, retention, and misuse of personal data by everything from law enforcement agencies to private companies. Moreover, in recent years, China has been a major promoter of the ‘safe city’ concept that focuses on surveillance-driven policing of urban environments – a practice that has been perfected in most Chinese cities (Triolo, 2020). Several Chinese companies have been at the forefront of China’s effort to export its model of safe city: Huawei, ZTE Corporation, Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology, Zhejiang Dahua Technology, Alibaba, and Tiandy (Yan, 2019).

China has been a significant exporter of surveillance technology worldwide, including to countries like Turkey. Chinese firms such as Hikvision and Dahua have supplied surveillance equipment, including facial recognition systems, to various nations. Reports indicate that Turkey has utilized facial recognition software to monitor and identify individuals during protests (Radu, 2019; Bozkurt, 2021).

Holistically, the global expansion of China’s urban surveillance model sparks significant concerns, particularly in relation to its potential to increase authoritarian practices in adopting countries. In the absence of robust counter mechanisms, the adoption of Chinese surveillance model by authoritarian states is only likely to augment.

Strategic Digital Information Operations (SDIOs)

Another interesting aspect of authoritarian regimes is the use of digital technologies in creating and spreading pro-regime propaganda and conspiracy narratives that benefit the regimes. This is happening extensively in the region, including Turkey, as a part of the manipulation of the people in order to impose control on them and silence the opposition. The pro-regime propaganda machine uses conspiracy theories with a dual strategy, defensive and offensive, to shape the public perception of the regime. Defensively, it seeks to portray the regime as a legitimate national authority, emphasising its adherence to the nation’s interests and well-being in a way that no legitimate alternative is imaginable. In these narratives, leaders are portrayed as heroic figures with exceptional qualities, and the system is presented as flawless and well-suited to the country’s needs. On the offensive front, the propaganda machine works to discredit any alternative to the current regime. Opposition figures are either assassinated, arrested or labelled as traitors, criminals, or foreign agents so they can be eliminated politically. To reach to this end, conspiracy theories link opposition figures to nefarious plots or foreign intervention, thus undermining the credibility of opposition narratives.

In recent years, propaganda and conspiracy theories have played a significant role in Turkey’s political landscape, influencing political narratives and public opinion. The Turkish government, particularly under President Erdoğan and his ruling party (AKP), has been known for using state-controlled or pro-government media to push certain narratives. The government’s media strategy includes promoting nationalistic themes, highlighting Turkey’s achievements under AKP rule, and portraying the government as the protector of national interests against both internal and external threats. The government often emphasizes Turkey’s sovereignty and positions itself against perceived Western interference, such as criticisms from the European Union or the United States. By doing so, it strengthens a nationalist image, resonating with citizens who view Turkey as being unfairly targeted by foreign powers. Propaganda often incorporates Islamic and conservative values to appeal to the AKP’s core voter base. Erdoğan’s speeches and media outlets supportive of the government emphasize the defense of Islamic culture and values, framing the AKP as a protector of both religion and national identity. Government narratives frequently depict opposition groups as threats to national stability. This includes not only political rivals but also groups like the Kurdish population, the Gülen movement (which is accused by Erdogan regime of being behind the 2016 coup attempt), and the pro-Kurdish HDP party, who are often associated with terrorism or disloyalty.

Additionally, conspiracy theories have been pervasive in Turkish political culture, often used to explain domestic unrest or justify political decisions. Here, pro-government media often propagate conspiracies about the opposition, portraying them as aligned with foreign powers or terrorist organizations. A persistent theme in Turkish political discourse is the idea that foreign powers or global financial institutions are working to undermine Turkey’s economy and political stability. Moreover, the failed coup attempt in July 2016 became a fertile ground for conspiracy theories. While the Turkish government attributed the coup attempt to Fethullah Gülen, a cleric who lived in exile in the United States for decades until his death, alternative theories continue to circulate. Some claim that foreign powers, particularly the US, were involved in the coup plot, while others suggest that elements within the Turkish government may have allowed the coup to proceed as a means to justify a subsequent crackdown on opposition. In the same vein, many conspiracy theories center around the idea that Western powers, particularly the US and Europe, are conspiring against Turkey to prevent it from becoming a major regional power. These theories often cite Turkey’s geopolitical location, its military interventions in the region, or its aspirations to become an independent economic powerhouse.

A significant portion of the mainstream media in Turkey is either directly controlled by the government or aligned with it. These outlets often echo government narratives, downplaying criticisms, and emphasizing government achievements or conspiracy-laden stories about opposition and foreign interference. Despite the dominance of pro-government media, social media platforms have become spaces for both opposition voices and pro-government voices. The government has sought to control these platforms through legal means, introducing laws to regulate social media and threatening to block access to platforms that do not comply with government requests to remove content.

Mechanisms of Diffusion

We observed that the diffusion of digital authoritarianism occurs in three main mechanisms: learning, emulation and cooperative interdependence.

Learning

It has been widely argued that countries across the globe learned from domestic and foreign experience to adopt various forms of digital authoritarian practices. This is more prominent in countries experiencing public unrest, like Turkey and Egypt. For example, they both have learned lessons from the Gezi Park and Tahrir Square protests, respectively. Despite many indications to this effect, for a long time there was a lack of smoking gun evidence pointing at this type of learning. In 2016, a series of leaked emails from Erdogan’s son-in-law and then Energy Minister Berat Albayrak’s account revealed that in the aftermath of the Gezi Park protests, the Erdogan regime identified its lack of control of digital space as a problem and sought solutions in the form of “set[ting] up a team of professional graphic designers, coders, and former army officials who had received training in psychological warfare” (Akis, 2022). In later years, the regime built one of the world’s most extensive internet surveillance networks on social media, particularly on X, according to Norton Symantec.

In regard to external learning, China (and Chinese companies) and Western private companies have been at the forefront of actors promoting internet censorship practices. China has been not only a major promoter but also a source of learning for middle powers when it comes to internet surveillance, data fusion, and AI. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) has become a key vehicle that drives these efforts. For example, during the 2021 SCO summit, Chinese officials led a panel titled the Thousand Cities Strategic Algorithms, which trained the international audience that included many developing country representations on developing a “national data brain” that integrates various forms of financial and personal data and uses artificial intelligence to analyze it. The SCO website reported that 50 countries are engaged in discussions with the Thousand Cities Strategic Algorithms initiative (Ryan-Mosley, 2022). China has also been active in providing media and government training programs to representatives from BRI-affiliated countries. In one prominent example, Chinese Ministry of Public Security instructed Meiya Pico, a Chinese cybersecurity company, to train government representatives from Turkey, Pakistan, Egypt, and other countries on digital forensics (see Weber, 2019: 9-11).

Moreover, the spread of internet censorship and surveillance technologies points to a highly probable learning event facilitated by western corporate entities. Specifically, Sandvine, NSO Group, and their parent company Francisco Partners, emerged at the center of the diffusion of DPI technology in most Middle Eastern countries except for Iran where the company is not allowed to operate. Recent revelations show that the company has played a significant role in facilitating the spread of ideas between countries. Alexander Haväng, the ex-Chief Technical Officer of Sandvine, explained in an internal newsletter addressed to the company’s employees that their technology can appeal to governments whose surveillance capacities are hampered by encryption. Haväng wrote that Sandvine’s equipment could “show who’s talking to who, for how long, and we can try to discover online anonymous identities who’ve uploaded incriminating content online” (Gallagher, 2022).

The spread of DPI practices in general and Sandvine’s technology in particular is also evidenced by the chronology of acquisition by developing countries. The list of countries contracted to buy Sandvine’s DPI technology includes Turkey, Algeria, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Eritrea, Jordan, Kuwait, Pakistan, Qatar, Russia, Sudan, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, and Uzbekistan (Gallagher, 2022). There is a clear trend here, both in terms of regime susceptibility and chronology of adoption. Turkey purchased Sandvine’s DPI technology in 2014, Egypt in 2016, and Pakistan did so in 2018 (Malsin, 2018; Ali & Jahangir, 2019).

It is highly likely that later adopters of this technology reviewed its performance in early adopters and decided upon their own adoption. We know from previous research that private companies can “influence the spread of state policies by encouraging the exchange of substantive and procedural information between states” (Garrett & Jansa, 2015: 391). Governments are required to understand details about the content of a technology and relevant institutional mechanisms to use it effectively. Corporations facilitate communication about these details. The existence of extensive links between Sandvine and authoritarian regimes, the similarities of how the tech has been used, and the sheer prominence of this company and its technology demonstrate a plausible argument for diffusion.

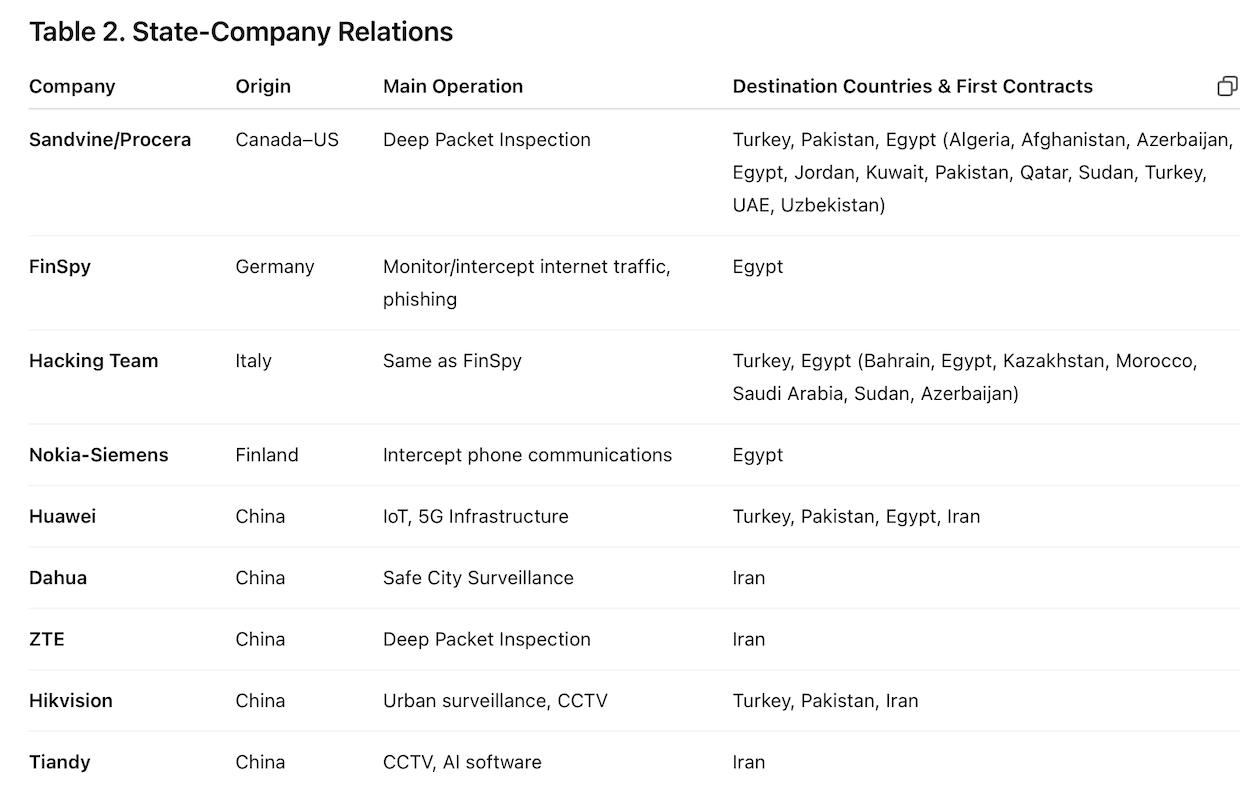

Using practice framework, we focus on ‘configurations of actors’ who are involved in enabling authoritarianism (Glasius & Michaelsen, 2018). In most instances, these actors are not states, but private companies (see Table 2). Moreover, contrary to perceived active role of Chinese companies, with the prime exception of Iran, it was Western tech companies that provided most of the high-tech surveillance and censorship capabilities to authoritarian regimes in the Muslim world including Turkey. These included, inter alia, US-Canadian company Sandvine, Israeli NSO Group, German FinFisher and Finland’s Nokia Networks.

Emulation

There’s evidence that authoritarian countries in the region like Turkey have emulated major powers, as well as each other, when it comes to internet censorship practices. Among other things, homophily of actors played important role as actors prefer to emulate models from reference groups of actors with whom they share similar cultural or social attributes (Elkins & Simmons, 2005). Political alignment and proximity among nations foster communication and the exchange of information (Rogers, 2010). We observe the influence of this dynamic between China and Russia, and political regimes in the Muslim world who are susceptible to authoritarian forms of governance to varying degrees.

Research noted that states tend to harmonize their policy approaches to align with the prevailing norms of the contemporary global community, irrespective of whether these specific policies or institutional frameworks align with local conditions or provide effective solutions. Notably, since most transfers originate from the core to the periphery, policy transfers to developing regions might be ill-suited and consequently ineffective. There’s evidence that adoption of city surveillance is driven by the desire for conformity rather than the search for effective solutions. China’s CCTV-smart city solutions are considered in the region to be “bold innovations” as they’ve gathered disproportionate attention from the developing countries across the world. However, there’s evidence that the countries adopt this technology because of their apparent promise rather than demonstrated success. For example, there has been a controversy about whether Huawei’s safe city infrastructure actually helps to reduce urban crime. In a dubious presentation in 2019, Huawei claimed that its safe city systems have been highly effective in reducing crime, increasing the case clearance rate, reducing emergency response time, and increasing citizen satisfaction. However, research by CSIS revealed that these numbers have been grossly exaggerated if not completely fabricated (Hillman & McCalpin, 2019).

Emulation and learning appear to be the major mechanisms through which such practices spread. First, by demonstrating the effectiveness of disinformation campaigns and propaganda – such as Russian interference in US presidential elections in 2016 and China’s propaganda around the Covid-19 pandemic – these countries have shown other regimes that similar tactics can be used to control their own populations and advance their interests (Jones, 2022). Second, China and Russia have acted as important sources of learning for authoritarian regimes. China has hosted thousands of foreign officials and members of media from BRI countries in various training programs on media and information management since 2017 (Freedom House, 2022). For example, in 2017, China’s Cyberspace Administration held cyberspace management seminars for officials from BRI countries. Chinese data-mining company iiMedia presented its media management platform which is advertised as offering comprehensive control of public opinion, including providing early-warnings for “negative” public opinions and helping guide the promotion of “positive energy” online (Laskai, 2019).

The governments in the Muslim world learned how to use the social media and other digital technologies for ‘flooding,’ which helps strengthen and legitimize their political regime. This is a part of a broader objective of shaping the information environment domestically and internationally (Mir et al., 2022). At home, these governments are attempting to mold their citizens’ conduct online. They hired social media consultants and influencers to do their propaganda. They learned how to flood the information space with propaganda narratives using troll farms and bots. For example, in Turkey, the AKP government created a massive troll army in response to the Gezi Protests in 2013. A 2016 study published by the cyber security company Norton Symantec shows that among countries in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, Turkey is the country with the most bot accounts on Twitter (Akis, 2022). In 2020, Twitter announced that it was suspending 7,340 fake accounts that had shared over 37 million tweets from its platform. Twitter attributed the network of accounts to the youth wing of the ruling AKP.

Through the aforementioned techniques, Turkey moved beyond strategies of “negative control” of the internet, in which the government attempt to block, censor, and suppress the flow of communication, and toward strategies of proactive co-optation in which social media serves regime objective. The opposite of internet freedom, therefore, is not necessarily internet censorship but a deceptive blend of control, co-option, and manipulation. As the public debate is seeded with such disinformation, this makes it hard for the governments’ opponents to convince their supporters and mobilize (Gunitsky, 2020).

Here, the practices appear to be a mixed bag of diffusion, convergence and even innovation on the part of some regional countries. There is some proof of learning on the part of the Turkish regime: Berat Albayrak’s emails reveal the government’s learning from the Gezi protests and intentional establishment of their own troll farms (Akis, 2022). Similarly, the Sisi regime learnt from the Arab Spring protests as well. While it is hard to find a smoking gun evidence of these regimes copying Russian or Chinese playbook, extensive links between some of these countries (such as Pakistan and Turkey), as well as between some of these countries and Russia/China (Turkey and Russia; China and Pakistan/Iran) brings some evidence of diffusion.

Cooperative Interdependence

We have observed that a cooperative interdependence has been at play when it comes to the diffusion of internet censorship practices from China to developing countries. Countries like Turkey are facing serious economic challenges and are in dire need of foreign direct investment. When tracing China’s technology transfer in these countries, a common thread emerges that tie most of the Chinese engagement to various forms of aid, trade negotiations, or grants. Prominently, China uses its Digital Silk Road (DSR) concept under the banner of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to push for adoption of its technological infrastructure and accompanying policies of surveillance and censorship in digital and urban environments (Hillman, 2021). For example, at the 2017 World Internet Conference in China, representatives from Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE signed a “Proposal for International Cooperation on the ‘One Belt, One Road’ Digital Economy,” an agreement to construct the DSR to improve digital connectivity and e-commerce cooperation (Laskai, 2019). The core components of the DSR initiative are smart (or “safe cities”), internet infrastructure, and mobile networks.

We do not argue that China is “forcing” these countries to adopt internet censorship practices. Rather, a cooperative interdependence works through changing incentive structures of BRI-connected states where financial incentives by China, coupled with technology transfer, promote China’s practical approach to managing the cyberspace as well. Indeed, BRI’s digital dimensions include many projects such as 5G networks, smart city projects, fiber optic cables, data centers, satellites, and devices that connect to these systems. In addition to having commercial value in terms of expanding China’s business of information technology, these far-reaching technologies have strategic benefit as they help the country achieve geoeconomic and geopolitical objectives that involve promotion of digital authoritarian practices and Chinese model of internet governance (Malena, 2021; Tang, 2020).

For example, Huawei’s growing influence in Turkey, and other regional countries such as Iran, Egypt, Pakistan, and particularly in the context of building their 5G infrastructure, is tied to these countries’ involvement in DSR projects. As mentioned above, all the abovementioned countries have signed agreements to cooperate with Huawei to build their 5G infrastructure. The latter is not merely an advanced technology, but also a vehicle of promoting an entire legal and institutional infrastructure for China. In 2017 the Standardization Administration of China (SAC) released the “BRI Connectivity and Standards Action Plan 2018-2020” which aims at promoting Chinese technical standards and improving related policies among BRI-recipient states across technologies including AI, 5G, and satellite navigation systems (Malena, 2021).

Cooperative interdependence such as loans, commercial diplomacy and other state initiatives are prominent mechanisms through which China spreads its urban surveillance practices. The Table 2 also demonstrates this process.

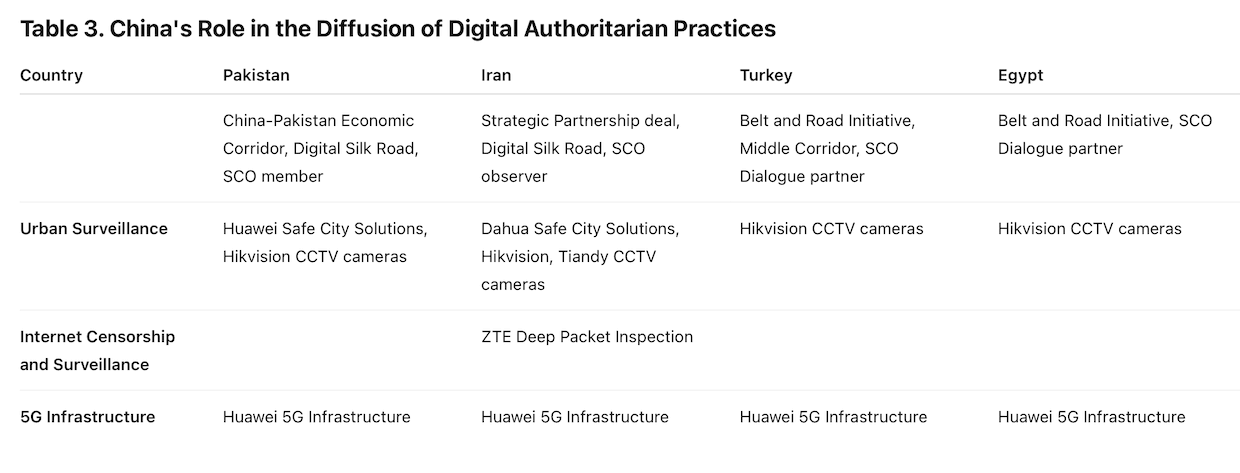

In the Muslim world, countries converged on importing China’s smart city platforms in recent years. A close collaboration between Chinese technology companies and authoritarian governments has led to the development of smart city infrastructures in multiple urban settings. Several Chinese companies have been at the forefront of this endeavor: Huawei, Hikvision, ZTE Corporation, Alibaba, Dahua Technology, and Tiandy (Yan, 2019). Huawei is a key source of diffusion of urban surveillance practices.

Huawei has established partnerships with major Turkish telecom companies, Turkcell and Vodafone TR, to implement smart city technologies in Samsun and Istanbul, respectively (KOTRA, 2021). Additionally, Turkey hosts one of Huawei’s 19 global Research and Development centers. In 2020, Turkcell became the first telecom operator outside China to adopt Huawei’s mobile app infrastructure, a system developed by Huawei in response to US sanctions that limited the use of certain Google software on Huawei devices. In 2022, Turk Telekom signed a contract with Huawei to build Turkey’s complete 5G network (Hurriyet, 2022). This infrastructure, known as Huawei Mobile Services (HMS), encompasses a suite of applications, cloud services, and an app store, which Huawei describes as “a collection of apps, services, device integrations, and cloud capabilities supporting its ecosystem” (Huawei, 2022).

Countries have also emulated China as the role model when it comes to urban surveillance practices. Indeed, China’s influence was highly discernible in the area of urban surveillance, where it has emerged as a role model and a key provider of high-tech tools (Germanò et al., 2023). To begin with, there are extensive linkages between sender (mostly China) and adopter countries in political and economic areas. These include the growing presence of China in regional economies, participation in China-dominated organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and cooperation with China on internet governance issues such as the statement in the UN by several countries. Moreover, China has long acted as a laboratory to observe the results of its unique blend of high-tech authoritarianism that combined extensive urban surveillance with control of the internet under the pretext of national security and sovereignty (see Mueller, 2020). The perceived success of Chinese officials in curbing crime, ensuring stability and efficient management of urban settings, including their draconian measures to control the spread of COVID-19, have elevated China as a role model to be emulated by many authoritarian countries, including those in the Muslim world (Barker, 2021).

The table below demonstrates China’s role in the diffusion of digital authoritarianism in the region including Turkey:

Conclusion

This research illustrates how Turkey’s adoption of digital authoritarian practices—encompassing restrictive legal frameworks, internet censorship, urban surveillance, and strategic digital information operations—has been propelled by a combination of learning from domestic unrest, emulating paradigms set by major authoritarian players like China and Russia, and capitalizing on cooperative interdependence forged through economic and strategic partnerships. Despite Turkey’s NATO membership and other Western affiliations, the government has selectively borrowed from authoritarian models, integrating advanced surveillance technologies and normative frameworks that restrict civic freedoms in the digital realm. In this ecosystem, private Western companies, operating with limited oversight, have facilitated the supply of censorship and surveillance tools, challenging conventional expectations that illiberal digital governance is primarily state-driven.

These findings highlight the urgent need to establish robust international cyber norms and regulations that delineate clear boundaries on digital governance, particularly in states with deep ties to the West. Multilateral fora, including the United Nations and the Council of Europe, can take the lead by defining the scope of “digital authoritarianism,” instituting transparent guidelines on surveillance exports, and ensuring that technology providers are held accountable for the potential misuse of their products. Greater emphasis on privacy protections and digital rights is equally critical, calling for comprehensive legislation within Turkey that shields citizens from unwarranted data collection. Support from the international community—through funding, awareness campaigns, and legal assistance—can empower local civil society groups to advocate for these rights, educate citizens on online privacy, and hold authorities to account.

A second imperative is responsible corporate behavior, where companies must be compelled—via legal and reputational mechanisms—to adhere to human rights standards and disclose how their technologies are deployed in countries like Turkey. Establishing an independent monitoring entity to track repressive digital practices, publicize violations, and elevate them to international organizations can reinforce such accountability. Equally important, regional and global cooperation on digital freedom can help counter Turkey’s authoritarian trajectory; governments committed to open societies should launch joint initiatives aimed at improving cybersecurity, combating disinformation, and expanding transparent governance models that respect human rights. Technical assistance and knowledge-sharing will be particularly valuable where Turkey’s domestic institutions seek alternatives to purely repressive tools.

Moreover, economic incentives can be used strategically to steer Turkey away from partnerships that reinforce authoritarian tendencies. By prioritizing trade relationships and development aid tied to ethical technology practices, major economic powers and international financial institutions can encourage Turkey to align more closely with suppliers committed to democratic values. Such an approach has the added benefit of opening the market to innovators developing privacy-enhancing products, thus providing viable alternatives to invasive surveillance systems. Finally, the use of strategic diplomatic channels remains a powerful lever. Dialogue within NATO, discussions at the European Union level, and broader diplomatic engagements allow Turkey’s partners to advocate for transparent, responsible digital practices. Joint resolutions or multilateral condemnations of authoritarian behaviors can further raise the political costs of continued repression.

Taken together, these initiatives underscore that countering digital authoritarianism in Turkey requires a proactive, holistic strategy. While local factors—such as domestic protest movements and longstanding elite interests—play a crucial role, the role of international actors and private corporations is equally significant. Each dimension, whether it be legal reform, corporate accountability, economic leverage, or diplomatic pressure, offers a piece of the puzzle. Coordinated action that weaves these elements into a cohesive approach is essential not only for Turkey but for the broader effort to preserve the open, rights-respecting nature of the global digital landscape. By challenging the unchecked diffusion of repressive technologies and policies, the international community can mitigate the risks posed by an ever-expanding authoritarian playbook and ensure that the internet remains a domain of freedom and democratic possibility.

Funding: This work was supported by Australian Research Council [Grant Number DP230100257]; Gerda Henkel Foundation [Grant Number AZ 01/TG/21]; Australian Research Council [Grant Number DP220100829].

Authors

Ihsan Yilmaz is Deputy Director (Research Development) of the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation (ADI) at Deakin University, where he also serves as Chair in Islamic Studies and Research Professor of Political Science and International Relations. He previously held academic positions at the Universities of Oxford and London and has a strong track record of leading multi-site international research projects. His work at Deakin has been supported by major funding bodies, including the Australian Research Council (ARC), the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, the Victorian Government, and the Gerda Henkel Foundation.

(*) Ali Mamouri is a scholar and journalist specializing in political philosophy and theology. He is currently a Research Fellow at the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation at Deakin University. With an academic background, Dr. Mamouri has held teaching positions at the University of Sydney, the University of Tehran, and Al-Mustansiriyah University, as well as other institutions in Iran and Iraq. He has also taught at the Qom and Najaf religious seminaries. From 2020 to 2022, he served as a Strategic Communications Advisor to the Iraqi Prime Minister, providing expertise on regional political dynamics. Dr. Mamouri also has an extensive career in journalism. From 2016 to 2023, he was the editor of Iraq Pulse at Al-Monitor, covering key political and religious developments in the Middle East. His work has been featured in BBC, ABC, The Conversation, Al-Monitor, and Al-Iraqia State Media, among other leading media platforms. As a respected policy analyst, his notable works include “The Dueling Ayatollahs: Khamenei, Sistani, and the Fight for the Soul of Shiite Islam” (Al-Monitor) and “Shia Leadership After Sistani” (Washington Institute). Beyond academia and journalism, Dr. Mamouri provides consultation to public and private organizations on Middle Eastern affairs. He has published several works in Arabic and Farsi, including a book on the political philosophy of Muhammad Baqir Al-Sadr and research on political Salafism. Additionally, he has contributed to The Great Islamic Encyclopedia and other major Islamic encyclopedias.

Nicholas Morieson is a Research Fellow at the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University. He was previously a Lecturer at the Australian Catholic University in Melbourne. His research interests include populism, religious nationalism, civilizational politics, intergroup relations, and the intersection of religion and political identity.

(**) Muhammad Omer is a PhD student in political science at the Deakin University. His PhD is examining the causes, ideological foundations, and the discursive construction of multiple populisms in a single polity (Pakistan). His other research interests include transnational Islam, religious extremism, and vernacular security. He previously completed his bachelor’s in politics and history from the University of East Anglia, UK, and master’s in political science from the Vrije University Amsterdam.

References

Access Now. (2022). “Internet Shutdowns in 2022.” Report. Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2022-KIO-Report-final.pdf.

Ahmed, Zahid Shahab; Yilmaz, Ihsan; Akbarzadeh, Shahram & Bashirov, Galib. (2023). “Digital Authoritarianism and Activism for Digital Rights in Pakistan.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). July 20, 2023. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0042

Akbarzadeh, Shahram, Amin Naeni, Ihsan Yilmaz, and Galib Bashirov. 2024. “Cyber Surveillance and Digital Authoritarianism in Iran.” Global Policy, March 14, 2024.

https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/14/03/2024/cyber-surveillance-and-digital-authoritarianism-iran.

Akbarzadeh, S., Mamouri, A., Bashirov, G., & Yilmaz, I. (2025). “Social media, conspiracy theories, and authoritarianism: between bread and geopolitics in Egypt.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2025.2474000

Akis, Fazil. (2022). “Turkey’s Troll Networks.” Heinrich Broll Stiftung. https://eu.boell.org/en/2022/03/21/turkeys-troll-networks.

Ali, Umer and Ramsha Jahangir. (2019). “Pakistan Moves to Install Nationwide ‘Web Monitoring System.” Coda Story.https://www.codastory.com/authoritarian-tech/surveillance/pakistan-nationwide-web-monitoring/.

Ambrosio, Thomas, and Jakob Tolstrup. (2019). “How Do We Tell Authoritarian Diffusion from Illusion? Exploring Methodological Issues of Qualitative Research on Authoritarian Diffusion.” Quality & Quantity 53(6): 2741-2763.

Ambrosio, Thomas. (2010). “Constructing a Framework of Authoritarian Diffusion: Concepts, Dynamics, and Future Research.” International Studies Perspectives 11(4): 375-392.

Anderson, Janna., & Rainie, Lee. (2020). “Many Tech Experts Say Digital Disruption Will Hurt Democracy.” Pew.https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/02/21/many-tech-experts-say-digital-disruption-will-hurt-democracy/.

Aziz, Sahar. F., & Beydoun, Khalid. A. (2020). “Fear of black and brown internet: policing online activism.” Boston University Law Review, 100(3), 1151-1192.

Bank, André, and Kurt Weyland, eds. (2020). Authoritarian Diffusion and Cooperation: Interests vs. Ideology. Routledge.

Barker, Tyson. (2021). “Withstanding the Storm: The Digital Silk Road, Covid-19, and Europe’s Options.” China after Covid-19 Economic Revival and Challenges to the World, Institute for International Political Studies and Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

Bashirov, G., S. Akbarzadeh, I. Yilmaz, and Z. Ahmed. (2025). “Diffusion of Digital Authoritarian Practices in China’s Neighbourhood: The Cases of Iran and Pakistan,” Democratization, DOI: 10.1080/13510347.2025.2504588

Bendrath, Ralf, and Milton Mueller. (2011). “The End of the Net as We Know It? Deep Packet Inspection and Internet Governance.” New Media & Society 13(7): 1142-1160.

Bilginsoy, Zeynep. (2021). “Facebook Bows to Turkish Demand to Name Local Representative.” AP News. https://apnews.com/article/turkey-media-social-media-6f2b1567e0e7f02e983a98f9dc795265

Bostrom, Nick. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bozkurt, Abdullah. (2021). “Turkey uses facial recognition to spy on millions, secretly investigates unsuspecting citizens.” Nordic Monitor. September 20, 2021. https://nordicmonitor.com/2021/09/turkey-uses-facial-recognition-to-spy-on-millions-secretly-investigates-unsuspecting-citizens/

Breuer, Anita. (2012). “The Role of Social Media in Mobilizing Political Protest: Evidence from the Tunisian Revolution.” German Development Institute Discussion Paper 10: 1860-0441.

Cattle, Amy E. (2015). “Digital Tahrir Square: An Analysis of Human Rights and the Internet Examined through the Lens of the Egyptian Arab Spring.” Duke J. Comp. & Int’l L. 26: 417.

Damnjanović, Ivana. (2015). Polity without Politics? Artificial Intelligence versus Democracy: Lessons from Neal Asher’s Polity Universe. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 35(3-4), 76-83.

Danao, Monique, and Sophie Venz. (2023). “Are VPNs Legal? The Worldwide Guide.” Forbes.https://www.forbes.com/advisor/au/business/software/are-vpns-legal/

Demirhan, Kamil. (2014). “Social Media Effects on the Gezi Park Movement in Turkey: Politics Under Hashtags.” In: Pătruţ B., Pătruţ M. (eds) Social Media in Politics. Public Administration and Information Technology, New York: Springer

Diamond, Larry, and Marc F. Plattner, eds. (2012). Liberation Technology: Social Media and the Struggle for Democracy. JHU Press.

Durac, Vincent, and Francesco Cavatorta. (2022). Politics and Governance in the Middle East. Bloomsbury Publishing.

ECCHR (European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights). (2023). https://www.ecchr.eu/en/

Feldstein, Steven. (2019). The Global Expansion of AI Surveillance. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/09/17/global-expansion-of-ai-surveillance-pub-79847accessed: 20/2/2021

Feldstein, Steven. (2021). The Rise of Digital Repression: How Technology Is Reshaping Power, Politics, and Resistance. Oxford University Press.

Freedom House (2021), Freedom on the Net 2020 Report, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/10122020_FOTN2020_Complete_Report_FINAL.pdf accessed: 1/3/2021

Freedom House. (2022). “Freedom in the World.” https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world

Freedom House. (2023). “Freedom on the Net 2023.” https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/Freedom-on-the-net-2023-DigitalBooklet.pdf

Gallagher, Ryan. (2022). “Sandvine Pulls Back From Russia as US, EU Tighten Control on Technology It Sells.” Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-03/sandvine-pulls-back-from-russia-as-us-eu-tighten-control-on-technology-it-sells

Gardels, Nathan., & Berggruen, Nicolas. (2019). Renovating Democracy: Governing in the Age of Globalization and Digital Capitalism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Garrett, Kristin N., and Joshua M. Jansa. (2015). “Interest Group Influence in Policy Diffusion Networks.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly. 15(3): 387-417.

Geere, Duncan. (2012). “How Deep Packet Inspection Works.” Wired. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/how-deep-packet-inspection-works

Germanò, Marco André, Ava Liu, Jacob Skebba, and Bulelani Jili. (2023). “Digital Surveillance Trends and Chinese Influence in Light of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Asian Journal of Comparative Law, 1-25.

Gheytanchi, Elham. (2016). “Iran’s Green Movement, social media, and the exposure of human rights violations.” In: M. Monshipouri (Ed.), Information Politics, Protests, and Human Rights in the Digital Age (pp. 177-195). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gilardi, Fabrizio. (2010). “Who learns from what in policy diffusion processes?” American Journal of Political Science.54(3): 650-666.

Gilardi, Fabrizio. (2012). “Transnational Diffusion: Norms, Ideas, and Policies.” Handbook of International Relations 2: 453-477.

Gunitsky, Seva. (2020) “The Great Online Convergence: Digital Authoritarianism Comes to Democracies .” War on the Rocks. February 18, 2020. https://warontherocks.com/2020/02/the-great-online-convergence-digital-authoritarianism-comes-to-democracies/.

Helbing, Dirk., et al. (2019). “Will Democracy Survive Big Data and Artificial Intelligence?” Scientific American.https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/will-democracy-survive-big-data-and-artificial-intelligence/

Hillman, Jonathan E. (2021). The Digital Silk Road: China’s Quest to Wire the World and Win the Future. Profile Books.

Hillman, Jonathan E., and Maesea McCalpin. (2019). “Watching Huawei’s” safe cities.” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Hong, Caylee. (2022). “‘Safe Cities’ in Pakistan: Knowledge Infrastructures, Urban Planning, and the Security State.” Antipode 54(5): 1476-1496.

Human Rights Watch. (2013). “China: Draconian Legal Interpretation Threatens Online Freedom.” https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/13/china-draconian-legal-interpretation-threatens-online-freedom

Human Rights Watch. (2022). “Turkey: Dangerous, Dystopian New Legal Amendments.” https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/14/turkey-dangerous-dystopian-new-legal-amendments

IHD. (2017). “Human Rights Violations of Turkey in 2016: De Facto Authoritarian Presidential System.” https://ihd.org.tr/en/2016-human-rights-violations-of-turkey-in-figures/.

Iosifidis, Petros, and Mark Wheeler. (2015). “The Public Sphere and Network Democracy: Social Movements and Political Change?.” Global Media Journal 13(25): 1-17.

Jenzen, Olu., et al. (2021). The symbol of social media in contemporary protest: Twitter and the Gezi Park movement. Convergence, 27(2), 414-437.

Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA). (2021). “Insights into Smart City Market in Turkey.” https://www.novusens.com/s/2462/i/KOTRA_Report_V33_ToC_fixed_after_Event.pdf.

Kynge, James, Valerie Hopkins, Helen Warrell, and Kathrin Hille. (2021). “Exporting Chinese Surveillance: the Security Risks of ‘Smart Cities’.” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/76fdac7c-7076-47a4-bcb0-7e75af0aadab

Laskai, Lorand. (2019). How China Is Supplying Surveillance Technology and Training Around the World. Privacy International.

Lynch, Marc. (2011). “After Egypt: The Limits and Promise of Online Challenges to the Authoritarian Arab State.” Perspectives on Politics. 9(2): 301-310.

Malena, Jorge. (2021). “The extension of the digital silk road to Latin America: Advantages and potential risks.” Brazilian Center for International Relations.

Malsin, Jared. (2018). “Throughout Middle East, the Web Is Being Walled Off.” Wall Street Journal.https://www.wsj.com/articles/throughout-middle-east-the-web-is-being-walled-off-1531915200.

Marczak, Bill, Jakub Dalek, Sarah McKune, Adam Senft, John Scott-Railton, and Ron Deibert. 2018. “Bad Traffic: Sandvine’s PacketLogic Devices Used to Deploy Government Spyware in Turkey and Redirect Egyptian Users to Affiliate Ads?” The Citizen Lab, https://citizenlab.ca/2018/03/bad-traffic-sandvines-packetlogic-devices-deploy-government-spyware-turkey-syria/

Margetts, H. (2013). “The Internet and Democracy.” In: The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies. Edited by W. H. Dutton, New York: Oxford University Press.

Michaelsen, Marcus. (2018). “Transforming Threats to Power: The International Politics of Authoritarian Internet Control in Iran.” International Journal of Communication. 12: 3856-3876.

Mir, Asfandyar, Tamar Mitts and Paul Staniland. (2022). “Political Coalitions and Social Media: Evidence from Pakistan.” Perspectives on Politics, 1-20.

Mueller, Milton L. (2020). “Against Sovereignty in Cyberspace.” International Studies Review 22(4): 779-801.

Negroponte, Nicholas. (1996). Being digital. New York: Vintage Books.

Our World in Data. (2021). “Fixed telephone subscriptions, 1960 to 2017.” https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/fixed-telephone-subscriptions-per-100-people?tab=chart&country=IRN~TUR~PAK~EGY

Ozturan, Gurkan. (2023). “Freedom on the Net 2023 Turkey Country Report.” Freedom House.https://www.academia.edu/108543121/Freedom_on_the_Net_2023_Turkey_Country_Report_Freedom_House

Polyakova, Alina., & Meserole, Chris. (2019). “Exporting digital authoritarianism: The Russian and Chinese models.” Policy Brief, Democracy and Disorder Series (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2019), 1-22.

Privacy International. (2019). “State of Privacy Egypt.” https://privacyinternational.org/state-privacy/1001/state-privacy-egypt.

Radavoi, Ciprian. N. (2019). “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Freedom, Rationality, Rule of Law and Democracy: Should We Not Be Debating It?” Texas Journal on Civil Liberties & Civil Rights, 25, 107.

Radu, Sintia. (2019). “How China and Russia Spread Surveillance.” U.S. News & World Report. September 20, 2019. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2019-09-20/china-russia-spreading-surveillance-methods-around-the-world

Ruijgrok, Kris. (2017). “From the Web to the Streets: Internet and Protests Under Authoritarian Regimes.” Democratization. 24(3): 498-520.

Ryan-Mosley, Tate. (2022). “The world is moving closer to a new cold war fought with authoritarian tech.” MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/09/22/1059823/cold-war-authoritarian-tech-china-iran-sco/?truid=%2A%7CLINKID%7C%2A

Sharman, Jason C. (2008). “Power and Discourse in Policy Diffusion: Anti-money Laundering in Developing States.” International Studies Quarterly. 52 (3): 635-656.

Stepan, Alfred, eds. (2018). Democratic transition in the Muslim world: a global perspective (Vol. 35). Columbia University Press.

Stone, Peter., et al. (2016). One Hundred Year Study on Artificial Intelligence: Report of the 2015-2016 Study Panel. Stanford University, Stanford, CA: http://ai100.stanford.edu/2016-report.

Strang, David, and Sarah A. Soule. (1998). “Diffusion in Organizations and Social Movements: From Hybrid Corn to Poison Pills.” Annual Review of Sociology. 24(1): 265-290.

Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Republic.com 2.0. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tan, Netina. (2020). “Digital Learning and Extending Electoral Authoritarianism in Singapore.” Democratization, 27(6): 1073-1091.

Tang, Min. (2020). “Huawei Versus the United States? The Geopolitics of Exterritorial Internet Infrastructure.” International Journal of Communication, 14, 22.

Triolo, Paul. (2020). “The Digital Silk Road: Expanding China’s Digital Footprint.” Eurasia Group.https://www.eurasiagroup.net/files/upload/Digital-Silk-Road-Expanding-China-Digital-Footprint.pdf.

Tusa, Felix. (2013). “How Social Media Can Shape a Protest Movement: The Cases of Egypt in 2011 and Iran in 2009.” Arab Media and Society, 17, 1-19.

Weber, Valentin. (2019). “The Worldwide Web of Chinese and Russian Information Controls.” Center for Technology and Global Affairs, University of Oxford.

Weber, Valentin. (2021). “The diffusion of cyber norms: technospheres, sovereignty, and power.” PhD diss., University of Oxford.

Wheeler, Deborah. (2017). Digital Resistance in the Middle East: New Media Activism in Everyday Life. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Yan, Yau Tsz. 2019. “Smart Cities or Surveillance? Huawei in Central Asia.” The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2019/08/smart-cities-or-surveillance-huawei-in-central-asia.

Yenigun, Halil Ibrahim. (2021). “Turkey as a Model of Muslim Authoritarianism?” In: Routledge Handbook of Illiberalism (840-857). Routledge.

Yilmaz, I., Caman, M. E., & Bashirov, G. (2020). “How an Islamist party managed to legitimate its authoritarianization in the eyes of the secularist opposition: the case of Turkey.” Democratization, 27(2), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1679772

Yilmaz, I. (2021). Creating the Desired Citizen: Ideology, State and Islam in Turkey. Cambridge University Press.

Yilmaz, I. (2025). Intergroup emotions and competitive victimhoods: Turkey’s ethnic, religious and political emigrant groups in Australia. Palgrave Macmillan Singapore.

Yilmaz, I. & Shipoli, E. (2022). “Use of past collective traumas, fear and conspiracy theories for securitization of the opposition and authoritarianisation: the Turkish case.” Democratization. 29(2), 320-336.

Yilmaz, I., Shipoli, E., & Demir, M. (2023). Securitization and authoritarianism: The AKP’s oppression of dissident groups in Turkey. Palgrave Macmillan Singapore.

Yilmaz, Ihsan; Akbarzadeh, Shahram & Bashirov, Galib. (2023). “Strategic Digital Information Operations (SDIOs).” Populism & Politics (P&P). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). September 10, 2023. https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0024

Yilmaz, Ihsan; Akbarzadeh, Shahram & Bashirov, Galib. (2023). “Strategic Digital Information Operations (SDIOs).” Populism & Politics (P&P). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). September 10, 2023. https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0024a

Yilmaz, I., Akbarzadeh, S., Abbasov, N., & Bashirov, G. (2024). “The Double-Edged Sword: Political Engagement on Social Media and Its Impact on Democracy Support in Authoritarian Regimes.” Political Research Quarterly, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129241305035

Yilmaz, I. and K. Shakil. 2025. Reception of Soft and Sharp Powers: Turkey’s Civilisationist Populist TV Dramas in Pakistan. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Yilmaz, I., Morieson, N., & Shakil, K. (2025). “Authoritarian diffusion and sharp power through TV dramas: resonance of Turkey’s ‘Resurrection: Ertuğrul’ in Pakistan.” Contemporary Politics, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2024.2447138

Ziccardi, Giovanni. (2012). Resistance, Liberation Technology and Human Rights in the Digital Age. Vol. 7. Springer Science & Business Media.