Please cite as:

Young, Alasdair R. (2026). “From Trade Skirmishes to Trade War? Transatlantic Trade Relations during the Second Trump Administration.” In: Populism and the Future of Transatlantic Relations: Challenges and Policy Options. (eds). Marianne Riddervold, Guri Rosén and Jessica R. Greenberg. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). January 20, 2026. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00128

DOWNLOAD CHAPTER 7

Abstract

The transatlantic economic relationship is the most valuable intercontinental relationship in the world. It is also uniquely interpenetrated by European and American firms, which are extensively invested in each other’s markets. Absent a comprehensive trade agreement, the transatlantic economic relationship has been characterized by ‘muddling through’ within the broad framework of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. The economic relationship between the United States (US) and Europe has periodically been punctuated by sometimes intense trade disputes. Historically, these disputes were narrowly focused and left the bulk of the transatlantic economic relationship untouched. Starting in spring 2025, the Trump administration dramatically departed from past US trade policy, imposing sweeping ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on all US trade partners as well as industry-specific tariffs on national security grounds. The European Union (EU) sought accommodation rather than confrontation, leading to a framework agreement in August. This agreement is fragile, but while it holds, it is a manifestation of ‘muddling through’, albeit under worse trading conditions than before Trump returned to office. It is possible that the relationship could deteriorate further.

Keywords: European Union; retaliation; tariffs; trade; Donald Trump; United States

By Alasdair Young*

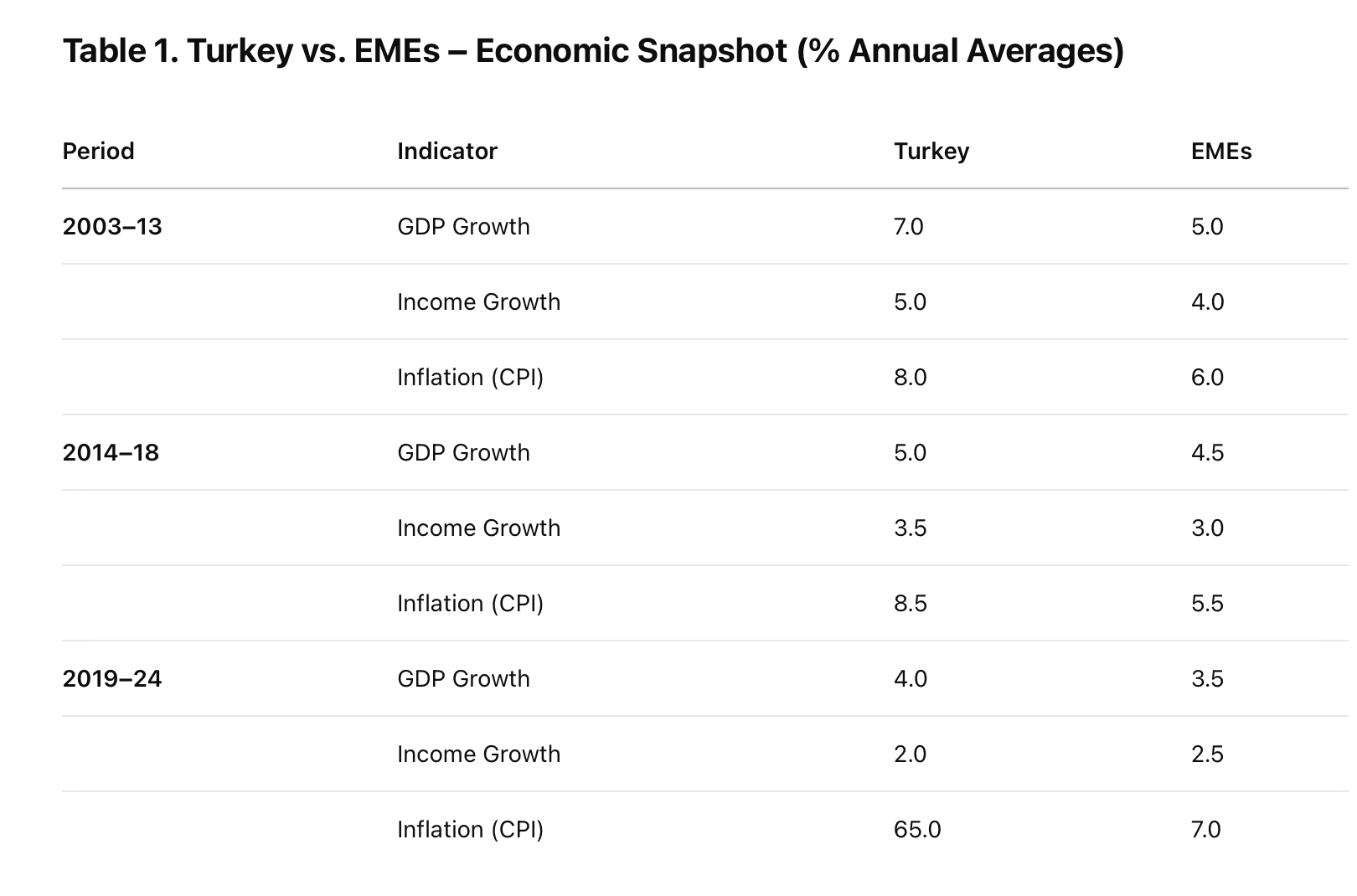

A Valuable and Previously Generally Calm Economic Relationship

The transatlantic economy is the ‘largest and wealthiest market in the world’ (Hamilton and Quinlen 2025, 2). Despite the current political focus on trade in goods, in which the United States has run a persistent deficit with the EU for more than a quarter century (Hamilton and Quinlen 2025, 12), the transatlantic economy is rooted primarily in mutual foreign direct investment (FDI). Almost 40% of the global stock of US FDI is in the EU, and EU firms account for slightly more than 40% all the FDI in the United States. The economic activity of transnational corporations in each other’s markets is therefore an important component of the transatlantic economy (see Table 7.1). The overall transatlantic economic relationship is much more balanced than a focus on just goods would suggest. Moreover, due to the extent of the investment relationship, 64% of US goods imports from Europe in 2023 occurred within the same firm as did 41% of US exports to Europe (Hamilton and Quinlen 2025, vii). Thus, goods imports are used as inputs in domestic production.

As there is no bilateral trade agreement between the EU and the United States – the most ambitious effort to create one, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations, ended with the first Trump administration – their trading relationship is subject to the rules and the most-favoured nation (MFN) tariffs they agreed to under the World Trade Organization (WTO) (see Chapter 8 in this report). Despite not having a trade agreement, in 2024, their average tariff rates were low and comparable: 1.47% on US imports from the EU and 1.35% on EU imports from the United States (Barata da Rocha et al 2025).

Table 7.1. The transatlantic economic relationship (2024)

(US$ billion)

| United States to the European Union | European Union to the United States | US–EU balance | |

| Goods | 372 | 609 | –237 |

| Services | 295 | 206 | 89 |

| Value-added by FDI (2022) | 494 | 456 | 38 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2025).

The transatlantic economic relationship has historically been relatively calm. It has, however, periodically been punctuated by high-profile trade disputes from the ‘Chicken Wars’ in the 1970s to disputes over bananas, hormone-treated beef, genetically modified crops and commercial aircraft subsidies in the 1990s and into the 2000s. Despite the attention they attracted, these disputes affected only a tiny fraction of transatlantic trade, and the more recent ones were contained within the WTO’s dispute settlement process (see Chapter 8 in this report). There were persistent, if episodic, efforts to try to address these transatlantic trade tensions, beginning with the ‘new transatlantic agenda’ in the 1990s. Historically, there was far more cooperation than conflict in the transatlantic economic relationship.

The Populist Turn in US Trade Policy

The transatlantic economic relationship has become much more confrontational under President Trump. He shares the populist view that trade is harmful and that the United States is being taken advantage of by foreigners, abetted by domestic elites (Baldwin 2025a, 1; Funke et al. 2023, 3280; Jones 2021, 29; and Box Figure 7.1). Trump considers the EU to be a particularly venal trade partner, describing it as ‘one of the most hostile and abusive taxing and tariffing authorities in the world’ (quoted in Gehrke 2025).

Figure 7.1 Trump’s populist view of trade

| Globalization has made the financial elite who donate to politicians very wealthy. But it has left millions of our workers with nothing but poverty and heartache. … We allowed foreign countries to subsidize their goods, devalue their currencies, violate their agreements, and cheat in every way imaginable. – ‘Declaring America’s Economic Independence’, 28 June 2016.We must protect our borders from the ravages of other countries making our products, stealing our companies, and destroying our jobs. Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength. – First Inaugural Address, 20 January 2017.… over the last several decades, the United States gave away its leverage by allowing free access to its valuable market without obtaining fair treatment in return. This cost our country an important share of its industrial base and thereby its middle class and national security. – The President’s 2025 Trade Policy Agenda, 3 March 2025.For decades, our country has been looted, pillaged, raped and plundered by nations near and far, both friend and foe alike. American steelworkers, auto workers, farmers and skilled craftsmen…watched in anguish as foreign leaders have stolen our jobs, foreign cheaters have ransacked our factories, and foreign scavengers have torn apart our once beautiful American dream. — ‘Liberation Day’ speech, 2 April 2025. |

In line with this rhetoric, President Trump took several steps during his first term that deviated from traditional US trade policy (Grumbach et al 2022, 237; Jones 2021, 71). He imposed a series of punitive tariffs on China in response to what the United States considered unfair trade practices. He also blocked the appointment of judges to the WTO’s Appellate Body, bringing the dispute settlement process to a halt (see Chapter 8 in this report). Despite characterizing the EU as ‘worse than China’ on trade in 2018 (Korade and Labott 2018), only the tariffs imposed on aluminium and steel imports under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (the so-called ‘Section 232 tariffs’) on the grounds of protecting national security directly impacted the EU. This use of Section 232 tariffs invoked a uniquely expansive understanding of national security that included trade causing substantial job, skill, or investment losses (Jones 2021, 74–75). The Trump administration also threatened tariffs on European governments that imposed digital services taxes on US platforms, although it did not impose them after those governments agreed to postpone implementation of the taxes. It was also set to impose national security tariffs on automobile imports when Trump left office. It did adopt enforcement tariffs on the EU as part of the long-running dispute over subsidies to Airbus, but that was in line with conventional US trade policy. The transatlantic economic relationship therefore deteriorated during the first Trump administration, but only modestly.

The Biden administration was not a huge fan of free trade (see, for instance, Sullivan 2023). It did not pursue bilateral trade agreements, seriously engage with WTO reform or enable the resumption of WTO dispute settlement. The United States also made extensive use of controls on semiconductor exports to China, including forcing European companies that used US intellectual property or inputs to comply with them. Under Biden, however, the United States focused on the economic and geopolitical challenges posed by China, so it adopted ceasefires with the EU over the steel and aluminium tariffs and in the aircraft dispute. Thus, while the transatlantic economic relationship did not fully return to where it was before Trump entered office, it was considerably better than when he left.

Trade policy in Trump’s second term, however, has made his first term look like a warm-up act.

A Shocked Transatlantic Economic Relationship

The second Trump administration has adopted a series of unprecedented trade measures that have dramatically impacted the EU. It significantly expanded its use of Section 232 tariffs, imposing them on a range of products important to the EU, including cars and car parts, aircraft and pharmaceuticals. President Trump also used the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) in an unprecedented way to impose ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on all US trading partners. President Trump initially announced that EU products, other than those subject to Section 232 tariffs or investigations, would be subject to an additional 20% tariff on top of the United States’ MFN tariff. He almost immediately announced that the additional tariffs would be lowered to 10% until 1 August to allow time for negotiations, but subsequently threatened to impose a 30% additional tariff on EU goods if no agreement were reached by the deadline.

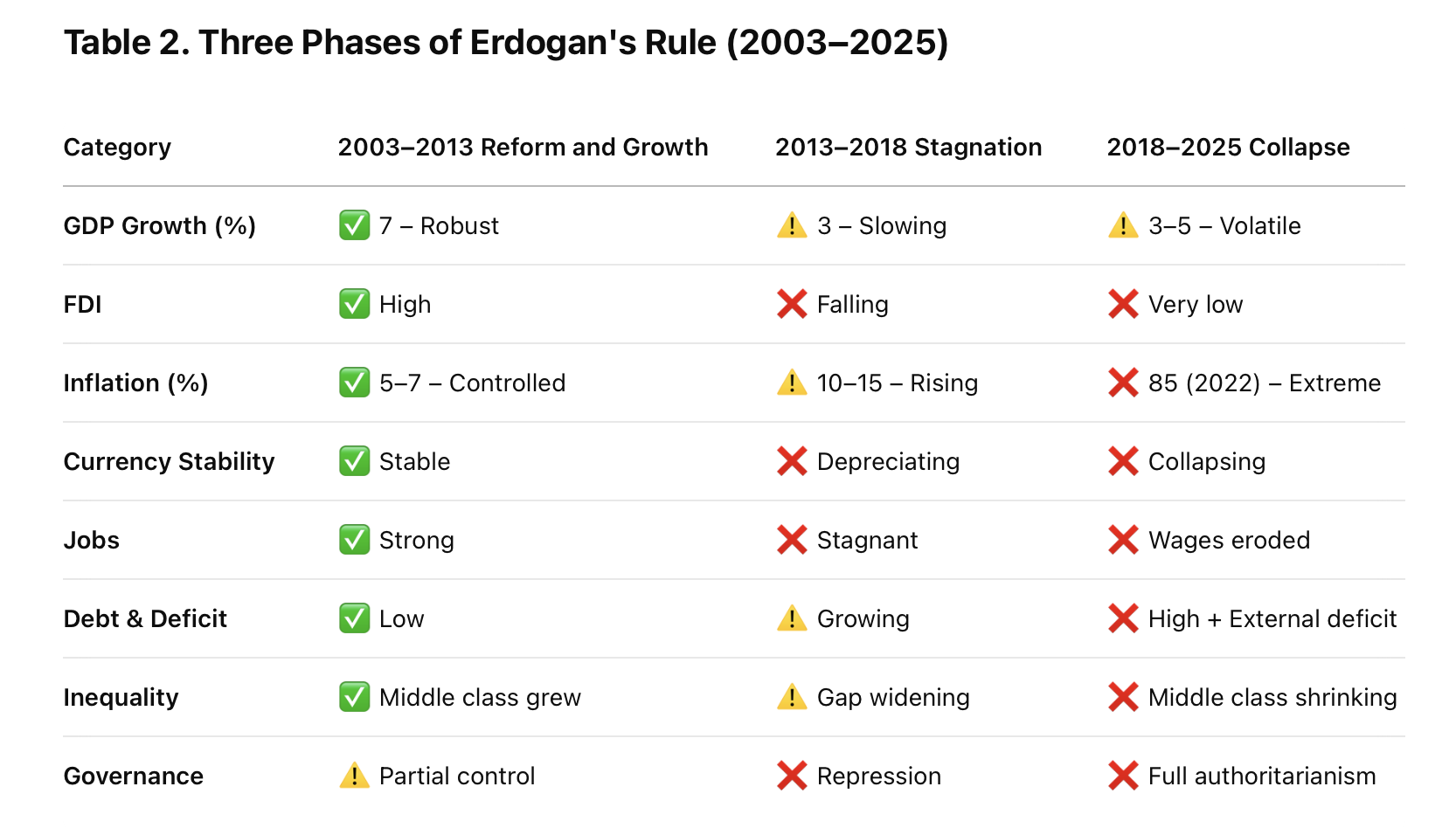

With the deadline looming, the United States and the EU reached a political agreement, which was subsequently elaborated in a framework agreement. This agreement established a baseline 15% tariff on most EU products (see Table 7.2). It had the effect of significantly reducing the tariffs the United States would have imposed on some of the EU’s most valuable exports, which were subject to Section 232 tariffs or investigations. Medicinal and pharmaceutical products, medicaments, cars and car parts and aircraft and associated parts accounted for 34% of the value of EU exports to the United States in 2024 (own calculations based on Eurostat 2025a). To secure this less-bad treatment, the EU agreed to eliminate all remaining tariffs on American industrial goods; give preferential market access for certain US seafood and non-sensitive agricultural products; and indicated that Europeans would purchase US weapons and liquified natural gas, and EU firms would invest in the United States (Politico 2025). The EU did not accede to US pressure to address its digital content and competition rules (Politico 2025). The European Commission (2025, 2) stressed that the deal ‘compares well’ to those secured by the United States’ other trade partners and thus EU exports remain competitive against other US imports. It also characterized the agreement as the ‘first important step’ toward reestablishing the stability and predictability of the transatlantic trading relationship and as a ‘roadmap’ for continuing negotiations to improve market access (European Commission 2025, 2).

Table 7.2 Framework agreement tariffs in context

| Sector | 2024 | Without the deal | With the deal |

| General (IEEPA ‘reciprocal’) | 3.4%* | 30% + MFN rateAdditional tariff for steel and aluminium content | 15% |

| Cars and car parts | 2.5% | 27.5% | 15% |

| Pharmaceuticals (patented) | 0–5% | 100%** | 15% |

| Pharmaceuticals (generic) | 0–5% | 0–5% | 0–5% |

| Semiconductors | 0–5% | Subject to Section 232 investigation | 15% |

| Aircraft | Low | Subject to Section 232 investigation | Low |

| Aluminium | 10% above the duty-free quota (based on historical levels) | 50% | New tariff-rate quota to be negotiated |

| Steel | 25% above the duty-free quota (based on historical levels) | 50% | New tariff-rate quota to be negotiated |

Notes:

* The United States’ average MFN rate, which is the more appropriate comparator to the headline rate for the new tariffs, applies to a bit over 60% of EU exports, so the average tariff rate is lower (Nangle 2025).

** Unless the manufacturer is building a plant in the United States.

Source: revised and updated from Berg (2025); European Commission (2025); WTO (2025)

The deal also included commitments to hold talks to address non-tariff barriers, to strengthen cooperation on economic security, including investment screening and export controls, and to enhance supply chain resilience, including for critical minerals, energy, and chips to power artificial intelligence (AI) (European Commission 2025; Politico 2025). These are long-standing areas of transatlantic cooperation that have yielded few results, with the notable exception of coordinating export controls on Russia in response to its war in Ukraine. It is therefore hard to assess how meaningful these new commitments are.

The EU’s commitment to eliminate industrial tariffs is unlikely to significantly affect EU industries, as these tariffs are generally low and already zero for all countries with which the EU has concluded free trade agreements (Berg 2025). The one exception is automobiles, where the EU’s tariff is relatively high (10%), and the United States is a major producer, although American cars are not necessarily to European tastes. The EU’s pledges on weapons and energy purchases, as well as new investments, are not binding (Berg 2025). The deal is very one-sided, but key EU industries – aviation, pharmaceuticals and semiconductors – avoided the worst that might have happened, and the EU did not concede much of economic significance. However, the agreement only mitigated the harm caused by higher US tariffs. By forestalling a trade war but not restoring the economic relationship to the way it was at the end of 2024, let alone improving it, the deal is a manifestation of ‘muddling through.’

The agreement, however, is fragile for three reasons. One is that there is opposition to the agreement in the EU. In particular, the European Parliament must approve lowering tariffs on US industrial and agricultural goods and it is considering amendments that would alter the agreement by making the preferential tariffs only temporary, allowing the EU to suspend preferential treatment if there is a surge in US imports and postponing EU tariff cuts on aluminium and steel until the United States reduces its own tariffs on the metals (Lowe 2025). The Commission will not be able to accept these changes to the deal, so there is likely to be a protracted process before the Parliament adopts the legislation necessary to implement the EU’s side of the deal. The United States has already expressed its unhappiness at the delay (Williams and Bounds 2025). Another reason the deal is fragile is that the Trump administration is known for coming back with further demands after an agreement has been reached (Sandbu 2025). For instance, since the deal, it has demanded that the EU ease environmental rules that impose burdens on US firms (Hancock, Foy and Bounds 2025). The United States, therefore, might threaten even higher tariffs to pressure the EU to change regulations that irritate US companies. The current deal is not great, but things could get worse.

The third source of fragility runs in the opposite direction. On 5 November 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments on whether President Trump’s use of IEEPA to impose sweeping tariffs exceeded his authority, as two lower courts had found. Based on the justices’ questioning, there is an expectation that the Court will rule against the President in the next few months. If it does, the IEEPA tariffs that are part of the reason for the EU-US deal will go away. As the real benefits (such as they are) for the EU are due to the caps on the Section 232 tariffs, it would probably not be in the EU’s interests to try to renegotiate the deal, even if new tariffs are not imposed under other provisions.

Possible Policy Options for the EU

Although the EU contemplated imposing retaliatory tariffs, it has thus far chosen compromise over confrontation. As a result, there has not been a transatlantic trade war. Several commentators have criticized the EU for not retaliating, which might have led the United States to accept terms more favourable to the EU (Alemanno 2025; Baldwin 2025a, xii; Bounds et al. 2025; FT Editorial Board 2025; Malmström 2025). French President Macron lamented that the EU was not ‘feared enough’ by the United States (quoted in Caulcutt et al 2025).

While sufficiently robust retaliation might have made the United States more willing to strike a more favourable deal, the downside risks for the EU were considerable. In particular, the United States has ‘escalation dominance’ for at least two reasons (see also Berg 2025; Gehrke 2025). First, the EU relies on the United States militarily, which is particularly important in the context of Russia’s war in Ukraine (Alemanno 2025; Berg 2025). Sabine Weyand, the EU’s director-general for trade, explained that ‘The European side was under massive pressure to find a quick solution to stabilise transatlantic relations with regard to security guarantees’ (quoted in Ganesh 2025). Second, European leaders have been more concerned than Trump about the adverse effects that imposing tariffs would have on their economies. Given those economic and security concerns, the member states were unwilling to support a trade war with the United States (Berg 2025; Bound et al. 2025; Malmström 2025).

There are three intersecting issues confronting the EU going forward: 1) How to mitigate the negative economic costs of the United States’ new, higher tariffs; 2) How to reduce the EU’s dependence on the United States to improve its bargaining position; and 3) How to respond should the United States come back with further demands for politically unacceptable changes to EU policies. The first and third of these issues might be affected by the Trump administration’s emerging concern about the harmful impact of tariffs on prices in the wake of dramatic Democratic victories in November’s elections (Desrochers 2025; Swanson et al. 2025).

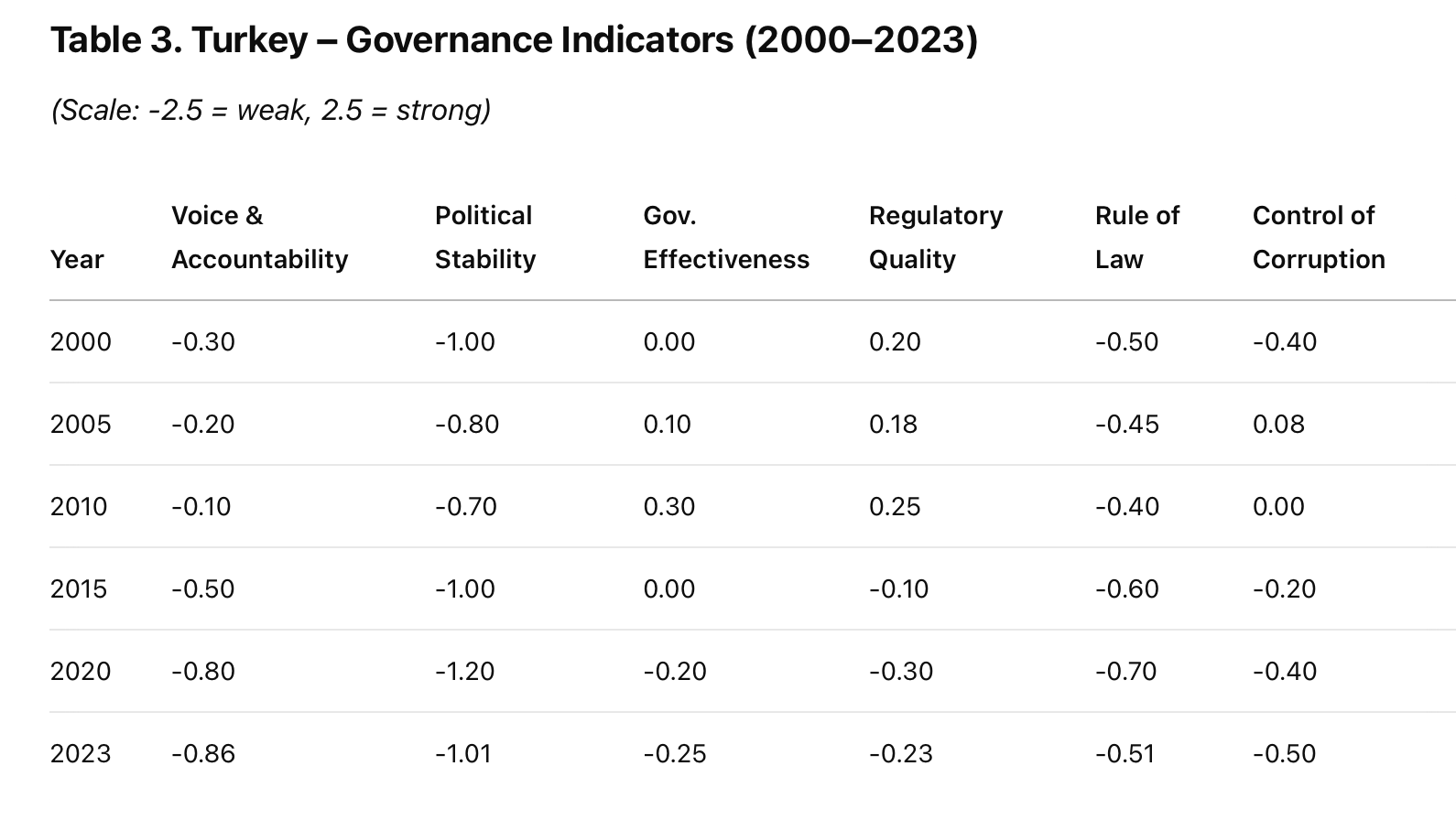

The EU has already taken steps to mitigate the consequences of losing access to the US market. The Commission has begun the process of signing the EU’s trade agreement with Mercosur and its upgraded agreement with Mexico. It has also finalized negotiations with Indonesia and is pursuing negotiations with India, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Even combined, however, these economies come nowhere near the importance of the US market (see Table 7.3). Given the EU’s economic and geopolitical concerns about China, a trade agreement with China is out of the question (see Chapter 6 in the present report). There are no other significant markets with which the EU does not already have preferential trade agreements. There is, however, scope to improve trading arrangements with the UK and Switzerland, which accounted for 13% and 7% of EU exports in 2024, respectively (García Bercero et al. 2024). Nonetheless, the EU will not be able to offset the loss of access to the US market through trade agreements. That said, the White House’s greater concern about the cost of living raises the possibility that the EU might be able to secure tariff relief for additional products (Foy 2025; Gus 2025).

Table 7.3 European Union exports to selected markets in 2024

| € million | Share of extra-EU exports | |

| United States | 532,697 | 21% |

| Mercosur | 55,168 | 2% |

| India | 48,701 | 2% |

| UAE | 44,389 | 2% |

| Malaysia | 17,854 | 1% |

| Indonesia | 9,810 | 0% |

| Philippines | 7,730 | 0% |

Source: Author’s own calculations based on Eurostat (2025).

Given the limited scope for securing improved market access, there is a strong case for the EU to look inward to pursue reforms that will both foster economic growth and competitiveness and enhance its military capabilities. The former will help to offset the loss of the US market, while the latter will help to redress the United States’ escalation dominance. The EU and its member states have launched initiatives on both goals, but they will take time to yield results, even with greater political impetus.

Brussels will face tough choices if Washington threatens to impose even higher tariffs unless the EU changes its rules on food safety, the environment and/or the digital economy. The EU could choose to retaliate to try to get the United States to back down. To avoid the adverse effects of imposing its own tariffs, the EU might target services – especially digital and financial services – where the United States runs a trade surplus (Gehrke 2025; Sandbu 2025). The EU might also restrict exports of key inputs to US manufacturing, since it accounts for 19% of such inputs and is a particularly important source of pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and manufacturing machinery (Baldwin 2025b). The EU could also limit US firms’ access to some key services – including insurance, shipping and commodity trading. Curbing those goods or service exports, however, would negatively affect European firms.

Thus, while the EU has the potential to inflict economic pain on the United States, doing so would significantly harm itself. Rather, it might be better for the EU to simply endure the tariffs and wait Trump out. Arguably, it was not China’s retaliatory tariffs that caused the United States to back down during the summer, but the domestic economic and political pain caused by sky-high US tariffs on key Chinese industrial inputs (Baldwin 2025b). Given the administration’s greater concern about the cost of living, particularly with the US midterm elections approaching in November 2026, it might refrain from imposing tariffs or be unable to sustain them for long. Should the EU choose to retaliate against new US tariffs, a trade war would be likely, which would imply the transatlantic trading relationship ‘breaking apart’. Continuing to ‘muddle through’ is probably the preferable approach.

(*) Alasdair R. Young is Professor and Neal Family Chair in the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He is Director of the School’s Center for Research on International Strategy and Policy and is Interim Associate Dean for Faculty Development for Georgia Tech’s Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts. He was Co-editor of JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies (2017–2022) and was Chair of the European Union Studies Association (USA) (2015–2017). Before joining Georgia Tech in 2011 he taught at the University of Glasgow for 10 years. Prior to that he held research posts at the European University Institute and the University of Sussex. He has written extensively on EU trade policy and transatlantic economic relations and performed consultancy work for the United States and United Kingdom governments and for the European Commission. Email: alasdair.young@gatech.edu

References

Alemanno, Alberto. 2025. “Europe’s Economic Surrender.” Project Syndicate, July 30. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/high-cost-of-eu-capitulation-to-trump-tariff-threats-by-alberto-alemanno-2025-07

Baldwin, Richard E. 2025a. The Great Trade Hack: How Trump’s Trade War Fails and the World Moves On. CEPR Press.

Baldwin, Richard E. 2025b. “Could the EU Repeat China’s Win Against Trump’s Tariffs?” Richard Baldwin Substack, July 21. https://rbaldwin.substack.com/p/could-the-eu-repeat-chinas-win-against-853

Barata da Rocha, Marta, Nicolas Boivin, and Nicolas Poitiers. 2025. “The Economic Impact of Trump’s Tariffs on Europe: An Initial Assessment.” Bruegel, April 17.

Berg, Andrew. 2025. “In Defence of a Bad Deal.” Insight, Centre for European Reform, August 7.

Bounds, Aimee, Henry Foy, and Ben Hall. 2025. “How the EU Succumbed to Trump’s Tariff Steamroller.” Financial Times, July 27. https://www.ft.com/content/85d57e0e-0c6f-4392-a68c-81866e1519c3

Casey, Cathleen A., and Jennifer K. Elsea. 2024. “The International Emergency Economic Powers Act: Origins, Evolution, and Use.” Congressional Research Service, R45618, January 30. https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R45618/

R45618.16.pdf

Caulcutt, Clea, Samuel Paillou, and Giacomo Leali. 2025. “Macron: EU Wasn’t ‘Feared Enough’ by Trump to Get Good Trade Deal.” Politico, July 30.

Desrochers, Daniel. 2025. “The White House Has Tried to Draw a Red Line on Tariffs. It’s Getting Blurry.” Politico, November 19.

European Commission. 2025. “Questions and Answers on the EU–US Joint Statement on Transatlantic Trade and Investment.” August 21. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/

presscorner/detail/en/qanda_25_1974

Eurostat. 2025a. “USA–EU: International Trade in Goods Statistics.” March.

Eurostat 2025b. Extra-EU Trade by Partner. Dataset code: ext_lt_maineu. Last updated November 14, 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ext_lt_maineu/

default/table?lang=en

Foy, Henry. 2025. “Europe Express: Tariff Reprieve.” Financial Times, November 21.

Financial Times Editorial Board. 2025. “The EU Has Validated Trump’s Bullying Trade Agenda.” Financial Times, July 30.

Funke, Manuel, Moritz Schularick, and Christoph Trebesch. 2023. “Populist Leaders and the Economy.” American Economic Review 113 (12): 3249–3288.

Ganesh, Janan. 2025. “Europe’s Necessary Appeasement of Donald Trump.” Financial Times, September 24.

García Bercero, Ignacio, Petros C. Mavroidis, and André Sapir. 2024. “How the European Union Should Respond to Trump’s Tariffs.” Bruegel Policy Brief 33/24, December. https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/how-european-union-should-respond-trumps-tariffs

Gehrke, Tobias. 2025. “Brussels Hold’Em: European Cards Against Trumpian Coercion.” European Council on Foreign Relations, Policy Brief. https://ecfr.eu/publication/

brussels-holdem-european-cards-against-trumpian-coercion/

Grumbach, Jacob M., Jacob S. Hacker, and Paul Pierson. 2022. “The Political Economy of Red States.” In The American Political Economy: Politics, Markets, and Power, edited by Jacob S. Hacker, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Paul Pierson, and Kathleen Thelen, 209–43. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gus, Cristina. 2025. “EU to Request Booze, Pasta, Cheese Tariff Exemptions from Trump Administration.” Politico, 21 November.

Hamilton, Daniel S., and Joseph P. Quinlan. 2025. The Transatlantic Economy 2025: Annual Survey of Jobs, Trade and Investment Between the United States and Europe. Johns Hopkins University SAIS/Transatlantic Leadership Network.

Hancock, Avery, Henry Foy, and Aimee Bounds. 2025. “US Demands EU Dismantle Green Regulation in Threat to Trade Deal.” Financial Times, October 8.

Jones, Kent. 2021. Populism and Trade: The Challenge to the Global Trading System. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Korade, Madeleine, and Elise Labott. 2018. “Trump Told Macron EU Worse than China on Trade.” CNN, June 11. https://www.cnn.com/2018/06/10/politics/trump-macron-european-union-china-trade

Lowe, Sam. 2025. “How to Do More Tariffs.” Most Favored Nation Substack, November 6. https://mostfavourednation.substack.com/p/how-to-do-more-tariffs

Malmström, Cecilia. 2025. “Trump’s Very Bad Trade Deal with Europe.” Realtime Economics, Peterson Institute for International Economics, July 31. https://www.piie.com/blogs/

realtime-economics/2025/trumps-very-bad-trade-deal-europe

Nangle, Tim. 2025. “US Tariffs Are Still Checks Notes Around 10 Per Cent.” Financial Times, October 8.

Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. 2025. “U.S. Trade Representative Announces 2025 Trade Policy Agenda.” March 3. https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2025/march/us-trade-representative-announces-2025-trade-policy-agenda

Politico. 2025. “What’s in the EU’s Framework Trade Deal with the US – And What Isn’t.” August 21. https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-frame-work-trade-deal-us-donald-trump-agreement/

Rojas-Suarez, Liliana, and Isabel Albe. 2025. “US Tariff Tracker: Measuring ‘Effective Tariff Rates’ Around the World.” Center for Global Development, April 29 (updated August 7).

Sandbu, Martin. 2025. “Free Lunch: The EU Doesn’t Need a Deal with Trump.” Financial Times, July 27.

Sullivan, Jake. 2023. “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Renewing American Economic Leadership at the Brookings Institution.” April 27.

Swanson, Ana, Maggie Haberman, and Thomas Pager. 2025. “Trump Administration Prepares Tariff Exemptions in Bid to Lower Food Prices.” New York Times, November 13.

Trump, Donald J. 2016. “Declaring America’s Economic Independence.” Politico, June 28.

Trump, Donald J. 2017. Remarks of President Donald J. Trump – As Prepared for Delivery: Inaugural Address, Washington, DC, January 20. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/

briefings-statements/the-inaugural-address/

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). 2025. “International Trade & Investment.” Accessed December 1, 2025.

Williams, Aimee, and Aimee Bounds. 2025. “Trump Trade Negotiator Hits Out at EU Delays in Cutting Tariffs and Rules.” Financial Times, November 16.

World Trade Organization. 2025. United States of America and the WTO. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/usa_e.htm