Are you passionate about global politics and understanding the dynamics that shape it? Are you looking for a way to expand your knowledge under the supervision of leading experts, seeking an opportunity to exchange views in a multicultural, multi-disciplinary environment, or simply in need of a few extra ECTS credits for your studies? Then consider applying to ECPS Summer School. The European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS) is looking for young people for a unique opportunity to assess the relationship between populism, war and crises in a five-day Summer School led by global experts from a variety of backgrounds. The Summer School will be interactive, allowing participants to hold discussions in a friendly environment among themselves in small groups and exchange views with the lecturers. You will also participate in a Case Competition on the same topic, a unique experience to develop problem-solving skills in cooperation with others and under tight schedules.

Overview

Our world is going through turbulent times on many fronts struggling with complex challenges emanating from various crises in different spheres of life. In parallel to this, we observe that these crises create convenient environments for populist politics and, in some cases, contribute to the emergence and success of populist parties. These developments align with the conclusion that populism usually occurs within a crisis scenario. Thus, we have decided to discuss the relationship between crises and populism at this year’s ECPS Summer School. To this end, for practicality, we categorise contemporary crises into five groups and will analyse them accordingly: political crisis and populism, economic crisis and populism, cultural crisis and populism, environmental crisis and populism, and health crisis and populism. Keeping in mind that crises vary in nature, and each has different consequences depending on the conjuncture in which they emerge; we will examine these five groups by taking into account the repercussions of the current international political context, particularly the war in Ukraine.

The lecturers for this year’s Summer School are Professor Kai Arzheimer, Professor Jocelyne Cesari, Professor Sergei Guriev, Dr Heidi Hart, Dr Gideon Lasco, Professor Nonna Mayer, Professor John Meyer, Professor Ibrahim Ozturk, Professor Neil Robinson, and Professor Ewen Speed.

The program will take place on Zoom, consisting of two sessions each day. Over the course of five days, interactive lectures by these world-leading experts will discuss the nexus between populism and the crises we are facing today from a variety of angles. The lectures are complemented by small group discussions and Q&A sessions moderated by experts in the field. The final program with the list of speakers will be announced soon.

Moreover, this year, the Summer School will comprise a Case Competition on a real-life problem within the broad topic of populism, crises and war. Participants will be divided into teams to work together on solving the case and are expected to prepare policy suggestions. The proposals of the participants will be evaluated by a panel of scholars and experts based on criteria such as creativity, feasibility, and presentation skills.

Our five-day schedule offers young people a dynamic, engaging and interdisciplinary learning environment with an intellectually challenging program presented by world-class scholars of populism, allowing them to grow as future academics, intellectuals, activists and public leaders. Participants have the opportunity to develop invaluable cross-cultural perspectives and facilitate a knowledge exchange that goes beyond European borders.

Who should apply?

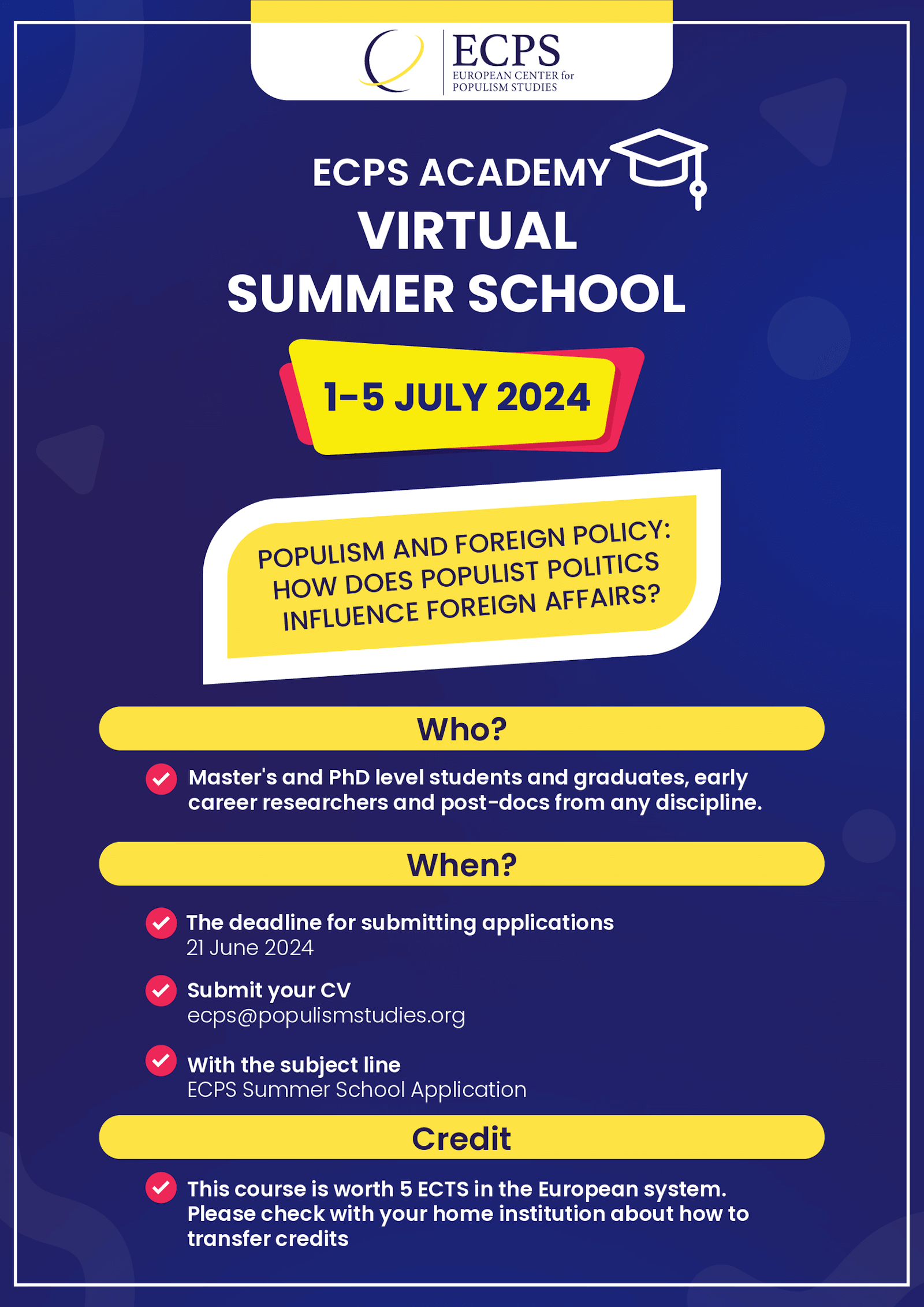

This unique course is open to master’s and PhD level students and graduates, early career researchers and post-docs from any discipline. The deadline for submitting applications is June 23, 2023. The applicants should send their CVs to the email address ecps@populismstudies.org with the subject line: ECPS Summer School Application.

We value the high level of diversity in our courses, welcoming applications from people of all backgrounds.

Evaluation Criteria and Certificate of Attendance

Meeting the assessment criteria is required from all participants aiming to complete the program and receive a certificate of attendance. The evaluation criteria include full attendance and active participation in lectures.

Certificate of Attendance will be awarded to the participants who attend at least 80% of the sessions. Certificates are sent to students only by email.

Credit

This course is worth 5 ECTS in the European system. If you intend to transfer credit to your home institution, please check the requirements with them before you apply. We will be happy to assist you; however, please be aware that the decision to transfer credit rests with your home institution.

Topics and Lecturers

Day 1: July 3, 2023

Political Crisis and Populism

Lecture 1

Dr Kai Arzheimer: Political crisis and populism

Bio: Kai Arzheimer is Professor of German Politics and Political Sociology at the University of Mainz, Germany. He has published widely on voting behaviour, particularly on voting for the radical right in Europe.

Abstract: In this short lecture, I will try to disentangle the relationship between populist actors and crises. I will start with an attempt to clarify both concepts. Following that, I will show that populists often benefit from events that are not crises in a strict sense but are framed as such. In turn, populist policies may lead to genuine political crises.

Moderator: Dr Vasiliki Tsagkroni

Bio: Dr Vasiliki (Billy) Tsagkroni is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at the Institute of Political Science, Leiden University. His research interests include far-right parties, populism and radicalisation, political discourse, narratives in times of crisis, political marketing and branding and policy making.

Lecture 2

Dr Neil Robinson: The Russian-Ukrainian war and the changing forms of Russian populism

Bio: Neil Robinson is Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Limerick. His research focusses on Russian and post-communist politics, particularly the political economy of post-communism and post-communist state building. He is the author and editor of books on Russia and comparative politics, including most recently Contemporary Russian Politics (Polity, 2018) and (with Rory Costello, editors) Comparative European politics. Distinctive democracies, common challenges (Oxford University Press, 2020), and has published articles on Russian politics in many journals including Europe-Asia Studies, Review of International Political Economy, International Political Science Review, Russian Politics.

Abstract: ‘Official populism’ developed in Russia in the 2010s to provide a project from Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012. This project centred on a particular relationship that Putin claimed existed between state and people in Russia. It was developed to counter other possible populist projects based on nationalism and/or anti-corruption campaigning. The ‘official populist’ project helped to close the political space in Russia after 2012 but was at risk of failing because it proposed a way of being ‘Russian’ that was dependent on the behaviour of forces and states not under Russian control, namely the former Soviet states, and particularly Ukraine, that Russia wanted to dominate through institutions such as the Eurasian Union. The risk of failure was one factor that helped push Russia to invade Ukraine in 2022. This invasion has opened up space to contest elements of the ‘official populism’ by new actors. The talk will examine some of these and what they might mean for Russia’s political development.

Reading List

Fish, M. Steven (2018) ‘What Has Russia Become?’, Comparative Politics, 50 (3): 327-46

Morris, J. (2022) ‘Russians in Wartime and Defensive Consolidation’, Contemporary History, 121 (837): 258–263.

Putin, V.V. (2021) ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181

Putin, V.V. (2022) ‘Address by the President of the Russian Federation’ http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67843(text and video version)

Reid, A. (2022) ‘Putin’s war on history. The thousand year struggle over Ukraine’, Foreign Affairs (101): 54-63.

Robinson, N. and S. Milne (2017) ‘Populism and political development in hybrid regimes: Russia and the development of official populism’, International Political Science Review, 38 (4), 412-25.

Tipaldou, S., and P. Casula (2019) ‘Russian nationalism shifting: The role of populism since the annexation of Crimea’, Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, 27 (3): 349-70.

Treisman, D. (2022). ‘Putin unbound. How repression at home presaged belligerence abroad’, Foreign Affairs (101): 40-53.

Moderator: Marina Zoe Saoulidou

Bio: Marina Zoe Saoulidou is a PhD candidate in Political Science and Public Administration at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA). Her thesis focuses on the dynamics of both left- and right-wing populist parties in Europe in the context of economic crises. Marina Zoe is an IKY Scholar (State Scholarships Foundation) and was awarded an NKUA Compensatory Fellowship (teaching assistantship). She is a Junior Research Fellow at the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP), and a member of the Hellenic Society of International Law and International Relations.

Day 2: July 4, 2023

Health Crisis and Populism

Lecture 1

Dr Ewen Speed: Health crisis and populism

Bio: Dr Ewen Speed is a Professor of Medical Sociology in the School of Health and Social Care at the University of Essex. He has research interests in health policy, particularly in the context of the NHS. He is also interested in critical approaches to understanding engagement and involvement in healthcare, and in critical approaches to psychology and psychiatry. He is currently an Associate Editor for the journal Critical Public Health. He is also a member of the National Institute of Health Research East of England Applied Research Collaboration, contributing directly to the Inclusive Involvement in Research for Practice Led Health and Social Care theme and is Implementation Lead for this theme.

Moderator: Caitlin R. Williams

Bio: Caitlin R. Williams is a PhD candidate and Adjunct Instructor in the Department of Maternal and Child Health at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. She is also a researcher and advocate whose work centers on scaling and sustaining policies, programs, and practices that advance health, rights, and justice. Meanwhile, she serves as a Research Consultant with the Instituto de Efectividad Clínica y Sanitaria in Buenos Aires, Argentina and a Research Collaborator with the Black Mamas Matter Alliance (Atlanta, GA, USA). Some of her recent projects include validating measures of global policy indicators for maternal health (including abortion access), assessing the threat posed by populist nationalism to human rights-based approaches to health, and analyzing national policies on obstetric violence and respectful maternity care. Caitlin has contributed her expertise to amicus briefs for cases in front of the Supreme Court of the United States, a memo to the U.S. Office of Civil Rights, and a statement to the Ways and Means Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Lecture 2

Dr Gideon Lasco: COVID-19 and the evolving nature of medical populism

Bio: Gideon Lasco, MD, PhD is a physician and medical anthropologist. He is senior lecturer at the University of the Philippines Diliman’s Department of Anthropology, affiliate faculty at the UP College of Medicine’s Social Medicine Unit, research fellow at the Ateneo de Manila University’s Development Studies Program, and honorary fellow at Hong Kong University’s Centre for Criminology. Dr. Lasco’s research projects have focused on contemporary health issues, including drug issues, COVID-19, health systems, and politics of health, and yielded over 50 journal articles and book chapters in the past five years. They have also led to two academic books: Drugs and Philippines Society (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2021), an edited volume which features critical perspectives on drug use and drug policy in the country, as well as Height Matters, forthcoming monograph on human stature with the University of the Philippines Press. He also maintains a weekly column on health, culture, and national affairs in the Philippine Daily Inquirer, as well as acolumn in SAPIENS, the online anthropology magazine, that focuses on the relationships of humans with other species.

Abstract: Over 3 years since the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous political analyses have extensively documented the ways in which political actors have responded to the health crisis, including the resort of many of them to populist performances. Less established, however, are the ways in which these actors evolve their political styles as the pandemic also evolves politically, socially, and epidemiologically. This presentation reviews and critically engages with the concept of medical populism, its elements of spectacularization, simplification, forging of divisions, as well as the literature on its figurations during the pandemic in different countries. It then (re)applies this concept to major events in the pandemic after the initial responses – e.g. the development of vaccines, the emergence of variants, the debates over whether the pandemic is over. Overall, this longer-term analysis shows that while politicians continue to dramatize their responses, offer simplistic solutions, and divide their publics, these characteristics do not necessarily coexist at a given political moment. Medical populism, then, viewed as a repertoire of styles rather than a fixed set of characteristics.

Reading List

Lasco, G. (2020). Medical populism and the COVID-19 pandemic. Global public health, 15(10), 1417-1429.

Moderator: Dr Vassilis Petsinis

Dr Vassilis Petsinis is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary (Institute of Global Studies). He is a political scientist with expertise in European Politics and Ethnopolitics. Dr Petsinis has conducted research and taught at universities and research institutes in Estonia (Tartu University), Germany (Herder Institut in Marburg), Denmark (Copenhagen University), Sweden (Lund University, Malmö University, Södertörns University, and Uppsala University), Hungary (Collegium Budapest/Centre for Advanced Study), Slovakia (Comenius University in Bratislava), Romania (New Europe College), and Serbia (University of Novi Sad). He holds a PhD in Russian & East European Studies from the University of Birmingham (UK).

Respondent: Dr Maria Paula Prates

Dr Maria Paula Prates is a medical anthropologist at the Department of Anthropology at UCL. She is interested in the embodied inequalities of the Anthropocene, specially that concerning Indigenous Women in lowland South America. She has worked with and among the Guaran-Mbyá in the last 20 years. She has ongoing research projects in reproductive justice, encompassing birthing, unconsented episiotomies, sterilization and c-section, and on the imbricated relation between Tuberculosis and environmental degradation. She worked as an Adjunct Professor in Anthropology of Health at UFCSPA, Brazil and moved to the UK in 2018 as a Newton International Fellowship holder awarded by the British Academy and Newton Fund.

Day 3: July 5, 2023

Economic Crisis and Populism

Lecture 1

Dr Ibrahim Ozturk: The abuse of the negative repercussions of an unmanaged globalisation in economics by the populists

Bio: Professor Ibrahim Ozturk is a visiting fellow at the University of Duisburg-Essen since 2017. He is studying developmental, institutional, and international economics. His research focuses on the Japanese, Turkish, and Chinese economies. Currently, he is working on emerging hybrid governance models and the rise of populism in the Emerging Market Economies. As a part of that interest, he studies the institutional quality of China’s Modern Silk Road Project /The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), its governance model, and implications for the global system. He also teaches courses on business and entrepreneurship in the Emerging Market Economies, such as BRICS/MINT countries. Ozturk’s Ph.D. thesis is on the rise and decline of Japan’s developmental institutions in the post-Second WWII era.

Dr. Ozturk has worked at different public and private universities as both a part-time and full-time lecturer/researcher between 1992-2016 in Istanbul, Turkey. In 1998, he worked as a visiting fellow at Keio University, in Tokyo, and again in 2003 at Tokyo University. He’s also been a visiting fellow at JETRO/AJIKEN (2004); at North American University, in Houston, Texas (2014-2015); and in Duisburg/Germany at the University of Duisburg-Essen (2017-2020).

Dr. Ozturk is one of the founders of the Istanbul Japan Research Association (2003-2013) and the Asian Studies Center of Bosporus University (2010-2013). He has served as a consultant to business associations and companies for many years. He has also been a columnist and TV-commentator. Dr. Ozturk’s native language is Turkish; he is fluent in English, intermediate in German, and lower-intermediate in Japanese.

Abstract: This seminar aims to introduce the concept of populism in economics in terms of its causes (i.e., globalization, income inequality, financial crisis), its mechanism of execution in economics by the populists (i.e., macroeconomics and institutions of populism), and its consequences. The economic argument for populism is straightforward: poor economic performance feeds dissatisfaction with the status quo. It fosters support for populist alternatives when that poor performance occurs on the watch of mainstream parties. Rising inequality augments the ranks of the left behind, fanning dissatisfaction with economic management. Declining social mobility and a dearth of alternatives reinforce the sense of hopelessness and exclusion. However, unlike the argument they use when they are in opposition, in power, by denying and undermining professional and autonomous institutions, discrediting science and scientific knowledge, and rejecting resource constraints in economics, populists would give even more harm to the people they promised to help.

Moderator: Dr Dusan Spasojevic

Bio: Dušan Spasojević is an associate professor at the Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Belgrade. His main fields of interest are political parties, civil society, populism and the post-communist democratization process. Spasojević is a member of the steering board of the Center for Research, Transparency and Accountability (CRTA) and the editor of Political Perspectives, scientific journal published by FPS Belgrade and Zagreb.

Lecture 2

Dr Sergei Guriev: The political economy of populism

Bio: Sergei Guriev, Provost, Sciences Po, Paris, joined Sciences Po as a tenured professor of economics in 2013 after serving as the Rector of the New Economic School in Moscow in 2004-13. In 2016-19, he was on leave from Sciences Po serving as the Chief Economist and the Member of the Executive Committee of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). In 2022, Sergei Guriev was appointed Sciences Po’s Provost. Professor Guriev’s research interests include political economics, development economics, labor mobility, and contract theory. Professor Guriev is also a member of the Executive Committee of the International Economic Association and a Global Member of the Trilateral Commission. He is also a Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research, London. He is a Senior Member of the Institut Universitaire de France, an Ordinary Member of Academia Europeae, and an Honorary Foreign Member of the American Economic Association.

Abstract: We synthesize the literature on the recent rise of populism. First, we discuss definitions and present descriptive evidence on the recent increase in support for populists. Second, we cover the historical evolution of populist regimes since the late nineteenth century. Third, we discuss the role of secular economic factors related to cross-border trade andautomation. Fourth, we review studies on the role of the 2008–09 global financial crisis and subsequent austerity, connect them to historical work covering the Great Depression, and discuss likely mechanisms. Fifth, we discuss studies onidentity politics, trust, and cultural backlash. Sixth, we discuss economic and cultural consequences of growth in immigration and the recent refugee crisis. We also discuss the gap between perceptions and reality regarding immigration. Seventh, we review studies on the impact of the internet and social media. Eighth, we discuss the literatureon the implications of populism’s recent rise.

Reading List

Guriev, S., Melnikov, N., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2021). 3g internet and confidence in government. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(4), 2533-2613.

Guriev, S., & Papaioannou, E. (2022). The political economy of populism. Journal of Economic Literature, 60(3), 753-832.

Henry, E., Zhuravskaya, E., & Guriev, S. (2022). Checking and sharing alt-facts. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(3), 55-86.

Moderator: Afonso Biscaia

Bio: Afonso Biscaia is a PhD student in Comparative Politics at the Instituto de Ciencias Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa. Afonso’s research focuses on digital political communication and right wing populism. His published work includes “Placing the Portuguese Radical Right-Wing Populist Chega Into Context: Political Communication and Links to French, Italian, and Spanish Right-Wing Populist Actors” (2022), and The Russia-Ukraine War and the Far Right in Portugal: Minimal Impacts on the Rising Populist Chega Party”, both in co-authorship with Susana Salgado.

Day 4: July 6, 2023

Environment, Religion and Populism

Lecture 1

Dr Heidi Hart: Populism and environmental crisis – From denial to the new deep ecology

Bio: Heidi Hart, a senior researcher at the ECPS and Linnaeus University (Sweden), is a researcher and educator based in the US and Scandinavia. She holds a Ph.D. in German Studies from Duke University and focuses on intersections of the arts and politics, including environmental crisis. She is currently a guest researcher at SixtyEight Art Institute in Copenhagen, where she has contributed curatorial work on climate art, and at the Linnaeus University Center for Intermedial and Multimodal Studies, where she is completing the research project “Instruments of Repair.”

Abstract: This talk provides an overview of the various populist strains of engagement with environmental crises. Beginning with pro-business climate denialism and moving to the surprising overlap between left and far-right ecological activism in Europe, I will show how these strains are not limited to one ideological viewpoint. Examples of nationalist, agrarian, nativist, traditionalist, and protectionist viewpoints will fill this discussion with a common thread of fear-based thinking. Examples of left-wing environmental populism further complicate the picture but arise from a more critical position. I will then trace the history of illiberal environmentalism through the Nazi period in Germany to contemporary appropriations of “deep ecology,” with several examples from popular culture that make this ideology more appealing than it might at first appear. Finally, I will invite all to discuss the Malthusian temptations implicit in wishing for a cleaner, less crowded, more protected planet.

Reading List

Buzogány, A., Mohamad-Klotzbach, C. (2022). Environmental Populism. In Oswald, M. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Populism. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80803-7_19

François, S., Nonjon, A. (2021). “Identitarian Ecology”: The Far Right’s Reinterpretation of Environmental Concerns. Illiberal Studies Program, 1 February 2021, https://www.illiberalism.org/identitarian-ecology-rights-reinterpretation-environmental-concerns/

Leigh, A. (2021). How Populism Imperils the Planet. The MIT Press Reader, 5 November 2021,https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/how-populism-imperils-the-planet/

Marquardt, J., Lederer, M. (2022) Politicizing climate change in times of populism: an introduction. Environmental Politics, 31:5, 735-754, DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2022.2083478

Ofstehage, A. et al. (2022). Contemporary Populism and the Environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 47, 671-696, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-124635

Serhan, Y. (2021). The Far-Right View on Climate Politics. The Atlantic, 10 August 2021,https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2021/08/far-right-view-climate-ipcc/619709/

Moderator: Dr João Ferreira Dias

Bio: João Ferreira Dias holds a Ph.D. in African Studies from ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (2016). He is a researcher at the International Studies Centre of ISCTE (CEI-ISCTE) in the research group Democracy, Activism, and Citizenship. He is also an associate researcher at the History Centre of the University of Lisbon and a member of the research network of the European Center for Populism Studies. He is a regular columnist in leading newspapers of the Portuguese press. His areas of research and interest are: Religious Anthropology (Yorùbá, Candomblé, Umbanda, rituals, thought patterns, politics of memory and authenticity), Political Science (culture wars, identity politics, nostalgia and politics of memory and nationalism, populism) and Constitutional Law (Constitutional Principles, Fundamental Rights, Religious Freedom).

Lecture 2

Dr Jocelyn Cesari: Why religious nationalism is not populism

Bio: Dr Jocelyn Cesari holds the Chair of Religion and Politics at the University of Birmingham (UK) and is Senior Fellow at the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University. Since 2018, she is the T. J. Dermot Dunphy Visiting Professor of Religion, Violence, and Peacebuilding at Harvard Divinity School. President-elect of the European Academy of Religion (2018-19), her work on religion and politics has garnered recognition and awards: 2020 Distinguished Scholar of the religion section of the International Studies Association, Distinguished Fellow of the Carnegie Council for Ethics and International Affairs and the Royal Society for Arts in the United Kingdom. Her new book: We God’s Nations: Political Christianity, Islam and Hinduism in the World of Nations, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2022 (https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/we-gods-people/314FFEF57671C91BBA7E169D2A7DA223). Other publications: What is Political Islam? (Rienner, 2018, Book Award 2019 of the religion section of the ISA); Islam, Gender and Democracy in a Comparative Perspective (OUP, 2017), The Awakening of Muslim Democracy: Religion, Modernity and the State (CUP, 2014). She is the academic advisor of www.euro-islam.info

Abstract: The lecture will offer an ideal type of the relations between religion and populism to show the difference between religious nationalism and populism; highlight the importance political history and secular cultures on the political role of religion in any given country; and include the international and transnational religious forms of populism.

Reading List

“Populism and religion: an intricate and varying relationship” by Christopher Beuter, Matthias Kortmann, Laura Karoline Nette and Kathrin Rucktäschel (pdf attached) https://forum.newsweek.com/profile/Jocelyne-Cesari-Professor-Religion-Politics-Georgetown-University-and-Harvard-University/37c1d797-c04c-4b41-9aef-8bdd4479d0de

Moderator: Dr Jogile Ulinskaite

Bio: Jogilė Ulinskaitė is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University. She defended her PhD thesis on the populist conception of political representation in Lithuania. Since then, she has been part of a research team that studies the collective memory of the communist and post-communist past in Lithuania. As a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University in 2022, she focused on the reconstruction of emotional narratives of post-communist transformation from oral history interviews. Her current research integrates memory studies, narrative analysis, and the sociology of emotions to analyse the discourse of populist politicians.

Day 5: July 7, 2023

Culture, Crisis and Populism

Lecture 1

Dr Nonna Mayer: Cultural explanations of right- wing populism… and beyond

Bio: Dr Nonna Mayer is CNRS Research Director Emerita at the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics of Sciences Po, former chair of the French Political Science Association 2005-2016), member of the National Consultative Commission for Human Rights (since 2016), co-PI of its annual Racism Barometer. Her current fields of expertise are electoral sociology, radical right populism, racism and anti-Semitism, intercultural relations.

Abstract: Taking the French case as an example, this presentation revisits and nuances the explanations of right wing populism in terms of “cultural backlash” and “cultural insecurity.” Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour both frame immigration as a deadly threat to French identity and values, nativist attitudes are the main driver of their voters. While anti feminism and sexism drive male votes for Zemmour, but not for Le Pen. However cultural factors are tightly mixed with social and economic factors.

Moderator: Dr Sorina Soare

Bio: Dr Sorina Soare is a lecturer of Comparative Politics at the University of Florence. She holds a PhD in political science from the Université libre de Bruxelles and has previously studied political science at the University of Bucharest. Before coming to Florence, S. Soare obtained funding from the Wiener Anspach foundation for 1 year Post-Ph Programme in St. Antony’s College, Oxford University. Her work has been published in Democratization, East European Politics, etc. She taught at the Central University of Budapest, Université libre de Bruxelles, University of Palermo and University of Bucharest. She works in the area of comparative politics. Her research interests lie primarily in the field of post-communist political parties and party systems, democratisation and institutional development.

Lecture 2

Dr John M. Meyer: The ambiguous promise of climate populism

Bio: Dr John M. Meyer is Professor in the Department of Politics at Cal Poly Humboldt, on California’s North Coast. He also serves in interdisciplinary programs on Environmental Studies and Environment & Community. As a political theorist, his work aims to help us understand how our social and political values and institutions shape our relationship with “the environment,” how these values and institutions are shaped by this relationship, and how we might use an understanding of both to pursue a more socially just and sustainable society. His current project explores the intersection between climate politics and the political potentials and dangers of populism. Meyer is the author or editor of seven books. These include the award-winning Engaging the Everyday: Environmental Social Criticism and the Resonance Dilemma (MIT, 2015) and The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Political Theory (Oxford, 2016). He is editor-in-chief of the international journal, Environmental Politics.

Abstract: The entanglements of climate change politics with populism are beginning to receive the attention they deserve. Many have argued that an exclusionary conception of “the people” and a critical account of scientific expertise make populism a fundamental threat to effective action to address climate change. While this threat can be real, I argue that it can also mislead us into reaffirming trust in mainstream political actors as a viable alternative. Instead, I explore opportunities for effective climate change action to be found in a more encompassing conception of populism, one rooted in an inclusive conception of “the people,” and an embrace of counter-expertise grounded in local knowledge of climate vulnerability and injustice.

Reading List

John M. Meyer, Power and Truth in Science-Related Populism: Rethinking the Role of Knowledge and Expertise in Climate Politics, Political Studies, 2023.

John M. Meyer, ‘The People’ and Climate Justice: Rethinking Populism and Pluralism within Climate Politics, DRAFT.

Kai Bosworth, Pipeline Populism: Grassroots Environmentalism in the Twenty-First Century, University of Minnesota Press, 2022.

Aron Buzogány and Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach, Environmental Populism, The Palgrave Handbook of Populism, 2022.

Will Davies, Green Populism?—Action and mortality in the Anthropocene, Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity, 2019.

Shane Gunster, Darren Fleet, Robert Neubauer, Challenging Petro-Nationalism: Another Canada Is Possible? Journal of Canadian Studies, Winter 2021.

Amanda Machin and Oliver Wagener, The Nature of Green Populism?, European Green Journal, 2019.

Jane Mansbridge and Stephen Macedo, Populism and Democratic Theory, Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 2019.

Jens Marquardt and Markus Lederer, eds., Operating at the Frontiers of Democracy? Mitigating climate change in times of populism, special issue, Environmental Politics, 2022.

Chantal Mouffe, Toward a Green Democratic Revolution, Verso, 2022. (excerpt here)

Moderator: Dr Tsveta Petrova

Bio: Dr Tsveta Petrova is a Lecturer in the Discipline of Political Science at Columbia University. She received her Ph.D. in Political Science from Cornell University in 2011 and then held post-doctoral positions at Harvard University and Columbia University. Her research focuses on democracy, democratization, and democracy promotion. Dr. Petrova’s book on democracy export by new democracies, From Solidarity to Geopolitics, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2014 and her articles have appeared in Comparative Political Studies, Journal of Democracy, Government and Opposition, Europe-Asia Studies, East European Politics & Societies, Review of International Affairs, and Foreign Policy among others. Her research has been supported by the European Commission, the US Social Science Research Council, American Council of Learned Societies, National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, Council for European Studies, Smith Richardson Foundation, and IREX. She further serves a Series Editor for the Memory Politics and Transitional Justice collection at Palgrave-Mcmillan as well as a Scholar with the Rising Democracies Network at the Carnegie Endowment and an Advisor to the Nations in Transit Program at the Freedom House.

Literature Review on Populism and Crises

By Anita Tusor

Populism usually occurs within a crisis scenario (Laclau, 1977: 175); however, crises vary in their nature and thus have several consequences and effects, affecting populist parties differently. This literature review aims to briefly showcase how different crises have affected populist parties. We have decided to merge UNDP’s Human Security Framework (1994) and combine its seven interdependent pillars into five fields to obtain a comprehensive selection on the different possible crises. The resulting fields have been populism and political crises, populism and health crises, populism and environmental crises, populism and economic crises, and populism and cultural crises.

Political Crisis and War

One of the main causes behind the recent rise of populism across the world has to do with the shortcomings of democracy, as can be observed in a constant weakening of traditional party identities and changing party functions (Kriesi & Pappas, 2015; Mair, 2002). This political crisis, according to Caiani and Graziano (2019) and Kriesi (2018), has reinvigorated populist actors all across the world, who have used it as an opportunity to channel popular discontent and turn it into electoral success. Furthermore, some authors have argued that rather than just triggering populist actors, populism frequently aims to act as a trigger for crisis and actively participate in the “spectacularization of failure” that underlies such crises, allowing them to pit the people against a dangerous other (Stavrakakis et al., 2017; Moffitt, 2015). So, to act as a trigger for a crisis, populist parties usually follow six major steps that are aimed at elevating a simple failure to the level of crisis and through which they also seek to divide the people from those who are responsible (Moffitt, 2015). According to Moffitt, these six major steps are (1) identity failure, which consists of choosing a particular failure and bring attention to it as a matter of urgency; (2) elevate to the level of crisis by linking into a wider framework and adding a temporal dimension, which is the act of linking the already chosen failure with other failures, locating it within a wider structural or moral framework in an attempt to make such failure to seem symptomatic of a wider problem; (3) frame the people against those responsible for the crisis, which consists of identifying those who are responsible for the crisis, and setting them against the so-called “people,” demonizing them and providing populist parties with an enemy to overcome and allowing them, first, to portray the so-alleged responsible for the crisis as a chronic problem and cause of every crisis, and, second, to offer populist parties a seemingly objective rationale for targeting their enemies, beyond outright discrimination; (4) use media to propagate performance, which is used by populist actors to disseminate and perpetuate a continuing sense of crisis; (5) present simple solutions and strong leadership, which refers to the presentation of themselves, through performative methods -such as portraying other political actors as incompetent and weak, offering simple answers for the crisis, and advocating the simplification of political institutions and processes-, as the only plausible alternative to solve the crisis; and (6) continue to propagate the crisis, which consists of the populist constant switch of the notion of crisis in order to overcome the unavoidable loss of interest by the population.

Lastly, the war in Ukraine has had a significant impact on Kremlin-backed populist parties, which have been forced to shift their positions from expressing support for Putin’s Russia to showing strong support for Ukraine to maintain their legitimacy in their respective countries (Albertazzi et al., 2022; Leonard, 2022). Notable among these Kremlin-supported populist parties are Lega, VOX, FN, and FPÖ, among others, as highlighted by Weiss (2020). The war has also led to the strengthening of mainstream pro-democratic parties, which have seen electoral successes as a result (Leonard, 2022; Pearce, 2022); however, the war has also had negative impacts on European economies and societies, which is expected to lead to dissatisfaction and distrust in democratic institutions, leading to a context that has already been beneficial for populist parties in the past, as they have been able to use sources of frustration to gain popular support (Docquier et al., 2022). Therefore, it can be assumed that European populist parties may adapt to this new context and use these sources again to gain popular support (Legrain, 2022). However, the literature on this topic is still limited. Furthermore, Farrell (2022) argues that the War in Ukraine may be actually benefiting populist radical right parties across European countries since it has put the raison d’être of such parties -the defense of the nation-state and national sovereignty- back at the top of the political agenda. This claim is supported by recent events, such as the victories of Hungary’s, Serbia’s, Sweden’s, and Italy’s radical right populist leaders, as well as in the increasing support for populist radical right leaders such as Marine Le Pen (Lika, 2022).

Health Crisis

Health crisis refers to a situation that poses a significant threat to public health, either in a specific location or globally. It can arise from a variety of causes, including disease outbreaks, natural disasters, environmental disasters, or other public health emergencies. Most recent examples of health crises challenging governments include the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and the Zika virus epidemic. These crises had a profound impact on individuals, communities, and entire populations, and required a coordinated response from governments, public health organizations, and other stakeholders to address the immediate and long-term effects.

As with other crises, populist may look at a health crisis as a “window of opportunity” and utilize it as a way to rally public support by presenting themselves as champions of the people and promoting policies that they claim will protect citizens from the perceived threat (Caiani & Graziano, 2019). However, although populist politicians are excellent at identifying problems and thematizing public discourse at times of crisis, they may be less successful at addressing them.

Populism can sometimes itself contribute to health crises by promoting distrust of scientific and medical experts, as well as government institutions responsible for public health; and by polarizing the political discussion about public health policies, along with underrating and undervaluing public service work. Moreover, populist leaders may downplay the severity of a medical crisis or spread misinformation, leading people to ignore public health guidelines or refuse to follow vaccination programs, which then exacerbate the spread of a disease and prolong the duration of a crisis. Moffit (2015: 195) reminds us that “populist actors actively perform and perpetuate a sense of crisis, rather than simply reacting to external crisis.” They pit the ordinary/true people against the elites, who in this case can be doctors and scientists as well, not exclusively the political establishment (Schwörer & Fernández-García 2022). In the case of Mexican populism, measures taken by “the Mexican populist government were based on negative beliefs towards expert scientific knowledge from outside the government; a disinterest in searching for more information from distant or unfamiliar sources” (Renteria & Arellano-Gault, 2021: 180), and to tackle the upcoming economic crisis, the primary approach would involve bolstering the core programs.

Summarizing the administrative steps and policies of populists during a health crisis, Lasco (2020) coined the term ‘medical populism’ which can be defined as a political style that centers on public health crises and creates a division between “the people” and “the establishment.” Medical populism has 4 main features: (1) downplaying of the pandemic, (2) dramatization or spectacularization of the crisis, (3) polarization of society where the ‘others’ include pharmaceutical companies, supranational bodies (WHO), the ‘medical establishment’ (i.e. ‘vertical divisions’) or ‘dangerous others’ like migrants that can be blamed for the crisis and cast as sources of contagion (i.e. ‘horizontal divisions’) and (4) making knowledge claims which included the spread of disinformation (Ibid.: 1418-1419). In most countries, “populist leaders have monopolized on discontent with COVID-19 policies and related conspiracy beliefs” (Eberl et al., 2021: 284) as well as created ‘populist tropes’ of testing and “shaped knowledge of the epidemic” to garner support (Hedges & Lasco, 2021: 83).

In some cases, populist could also block the coordination of a global response as they oftentimes prioritize national interests over global ones (Spilimbergo, 2021), leading to delays in sharing information and resources that are necessary to combat the crisis effectively. Cepaluni and colleagues (2021: 1) found that – although earlier research demonstrated that “more democratic countries suffered greater COVID-19 deaths per capita and implemented policy measures that were less effective at reducing deaths than less democratic countries in the early stages of the pandemic” – at the end, populism were associated “with a greater COVID-19 death toll per capita, although the deleterious effect of populism is weaker in relatively more democratic states.” Fernandes and de Almeida Lopes Fernandes (2022) identified strong evidence of link between poor response to the pandemic and right-wing populism in Brazil, where Jair Bolsonaro was one of the most prominent denialists of the effects of the global health crisis. Furthermore, there is also a correlation between relying on social media as the primary means of obtaining information, voting for populists and being more receptive to misinformation, including conspiracy theories (Ferreira, 2021).

Times of crisis exacerbate some of the above-mentioned effects. In addition, asking the questions, why some citizens ignore common logic, scientific results and medical advice, Eberl et al. (2021: 272) demonstrated a “positive relationship of populist attitudes and conspiracy beliefs, above and beyond political ideology.” Despite this, some state that there is no clear evidence that populists systematically mismanaged the pandemic (Spilimbergo, 2021), although the pandemic is still ongoing as of March 2023 according to the WHO. Further evaluation of the management of the Covid-19 health crisis by populist forces therefore must wait.

Focusing on the first years of the pandemic, Kavakli (2020) observed slower reaction to the pandemic by populist and economically right-wing governments. These administrations were also more likely implementing fewer health measures and required no or limited social isolation compliance due to the lack of trust in health care professionals and scientists. The uncertainties communicated in expert messaging at the wake of the pandemic has reflected the realities of the learning process among medical professionals, nonetheless the lack of clarity deepened public anxiety and distrust in the competence of officials and redoubled feelings of being left behind and alone among voters at a time when people’s need for competent elites were heightened (Csergő, 2021). This then has been exploited by populists who challenged what counts as credible knowledge. Right-wing populists have attracted the most skeptical segment of the general public and mobilized masses against ‘science-driven’ measures. Former U.S. President Donald Trump has even decided to withdraw from the WHO questioning the credibility of the organization. This disengagement from WHO was a divisive decision: According to Panizza (2005), if populism serves as a reflection of democratic institutions, then it is also true for global governance organizations such as the WHO, as argued by Reddy et al. (2018). However, Mazzeloni and Ivaldi found that “right-wing populist voters were more likely to prioritize health over the economy, and that this was very significant among those voting for Trump in the US, Alternative für Deutschland in Germany, Lega and Fratelli d’Italia in Italy, and the SVP in Switzerland.” Therefore, withdrawal from the WHO amid the pandemic seems like a surprising choice.

One of the central questions of the literature is investigating the question of whether the Covid-19 pandemic has strengthened or weakened the discursive opportunities of populist political parties. Schwörer and Fernández-García (2022) argue the latter but indicate that populist radical right parties (PRRP) “are able to electorally survive a pandemic that does not deliver favorable nativist discourses opportunities by emphasizing their populist profile and blaming elites without references to immigration” (no pagination). Their manual content analysis of Twitter discourses of populist radical right parties (PRRP) from 6 West European country found that as nativist messages become restricted with PRRP’s growing support against restrictions (post first wave); they started “using anti-elitist demonizing discourses against the national government accusing it of abolishing democracy and undermining freedom” (no pagination). By this reframing, PRRPs positioned the health crisis as a domestic political crisis instead of an international one. Some presidents and prime ministers went as far as using war metaphors such as ‘fighting the virus’, ‘defeating the virus’ or ‘the war against the virus’ (Ajzenman et al., 2020; Wodak, 2022). This discourse strategy was adopted by French president Emmanuel Macron and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán among others, although the former tried to justify strict measures by this rhetoric, while the latter aimed to fight panic and instrumentalize the crisis to further undermine Hungarian democracy.

Amid the health crisis, authoritarian orientation of populist parties in place has become evident. In line with the theory, in-group threat is central to an authoritarian attitude (Feldmann & Stenner, 1997; Adorno et al. 2019), research conducted during the pandemic has found that voters associated with right-wing authoritarian views and ethnocentric, prejudicial attitudes become more nationalistic and anti-immigrant as levels of anxiety grow generated by the perceived threat of a virus (Hartman et al., 2021: 1282).

As Spilimbergo (2021) and Eberl et al. (2021) states, the pandemic did not kill populism, it might have weakened support for it, but post-pandemic issues – fueled by economic insecurity – may lead to yet another surge of populist support among voters. Biancalana and colleagues (2021) had come to a similar conclusion after examining the emerging literature on the relationship between populism and health crisis. On the contrary, Guliano and Hubé (2021) analyzed 8 European countries in the context of the pandemic and found that the health crisis has only benefited populist parties in office (who sustained or significantly improved their primacy, while hindered their prospects in opposition. Either way, populism will stay with us.

Environmental Crisis

The escalating environmental crisis has prompted a wide range of groups, organizations, and political parties to devise innovative strategies to address this global predicament. Eco-populist actors, organizations, and parties are playing a crucial role in demanding systemic change and attempting to overhaul the exploitative capitalist system, identified as a primary cause of the climate crisis due to its constant Greenhouse Gas emissions and exploitation of natural resources (IPCC, 2022; Torres-Wong, 2019). Such actors range from left-wing organizations, associations, indigenous groups, and NGOs to far-right political parties and right-wing extremist armed militias (see Middeldorp & Le Billon, 2019; Haggerty, 2007; Wittmer & Birner, 2005), which have seen the current climate crisis as an opportunity to gain broader support and impose their nativist ideas. In fact, there are several far-right and Populist Radical Right Parties that have renewed their interest in environmental issues, thus integrating ecological stances in their agendas ultimately aimed at promoting their nationalist views (Lubarda, 2022; Forchtner & Kølvraa, 2015).

Hence, populist parties approach the ongoing climate crisis in different ways, depending on their ideology and political agenda. Right-wing populists around the world have seriously challenged the narrative of climate change as a global challenge that rests on complex interdependencies, accumulated greenhouse gas emissions, and a threat to the world population as a whole, as could have been observed in national leaders like Donald Trump, Rodrigo Duterte, and Jair Bolsonaro, who led mobilizations against climate change mitigation efforts (Marquardt & Lederer, 2022). Nonetheless, as above-mentioned, other far-right and Populist Radical Right Parties have adopted different approaches to the ongoing climate crisis, such as the Front National’s approach of “patriotic ecology,” which aims to protect the French people, culture, and environment from climate change, pollution, and resource depletion by emphasizing French natural resources and national identity, but ultimately masks nativist and Eurosceptic policies; the United Kingdom Independence Party’s (UKIP) approach to the British countryside by politicizing the environmental debate and blaming the European Union, overpopulation, and immigration for its deterioration; or the Czech far-right’s discourse on the environment, which criticizes eco-terrorism and evokes a spiritual and nativist Czech environment (Boukala & Tountasaki, 2020; Tarant, 2020; Turner-Graham, 2020; Forchtner & Kølvraa, 2015).

On the other hand, populist parties on the left may adopt a progressive stance, and argue that the crisis is caused by the capitalist system and the exploitation of workers and natural resources by the rich and powerful elites, claiming that the climate crisis disproportionately affects marginalized communities and advocating for more redistributive and egalitarian policies to address it, as can be observed in Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa but also civil society groups like the climate justice movement, Fridays for Future or Extinction Rebellion, that have popularized progressive action on climate change through unconventional modes of protest, disruptive arguments, and demands for systemic change (Scherhaufer et al., 2021; Brünker et al., 2019; Kingsbury et al. 2019, Figueres et al., 2017).

In sum, how populist actors tackle the ongoing environmental crisis vary in relation to their agenda and their ideological interests; while right-wing populist actors may either embrace skepticism and denial or address the issue through the implementation of nativist and protectionist policies, left-wing populist actors and parties usually opt for the design and execution of more redistributive policies that approach the problem from a more systemic perspective.

Economic Crisis

The vast majority of the current literature focuses on the whys and wherefores rather than the effects and impacts of populism, seeking to assess whether the rise of populism is best seen as driven by economic or cultural factors, perhaps both (Iversen & Soskice, 2019; Rooduijn & Burgoon, 2018). In the next section, cultural backlash theory (Inglehart & Norris, 2016: 30) is discussed in detail, therefore, here we focus more on the explanation of economic materialists who identify economic insecurities as the cause of populism such as financial crises, austerity and harsh economic measures, a pushback against neoliberalism and globalization (Rodrik 2018, Snegovaya 2018).

Economic insecurity as a driver of populism has been investigated extensively following the 2008-euro crisis (Margalit, 2019). Research investigated the developments which eroded voters’ trust in the political system and led those on the losing side to opt for populist parties, to have a break from the status quo and offer seemingly appealing solutions to voters’ economic malaise – be it trade protectionism, building a border wall, or exiting the EU. Sonno et al. (2022) examined the impact of the financial crisis on the middle class suggesting that “financial crisis broadened the pool of disappointed voters, prompting, on the supply side, political parties to enter the political arena with platforms giving the disillusioned voters a new hope for simple and monitorable protection.”

Guiso and others (2017) studied the demand for and supply of populism, both empirically and theoretically. They document a link between individual-level economic insecurity and distrust toward political parties, voting for populist parties, and low electoral participation. Economic crises are generally known to create a sense of dissatisfaction and disillusionment among citizens. In some cases, it can also create a power vacuum or a sense of uncertainty that allows populist politicians to gain more influence or even come to power. This can be seen in some recent examples of populism, such as the rise of far-right parties in Europe in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008 or the 2015 immigration crisis in Europe. As we could see, populist politicians were able to take advantage of voters’ dissatisfaction by tapping into people’s fears and offering simple nationalist solutions to complex socio-economic problems. Some specifically investigated (Beck, Saka & Volpin, 2020) why the right-wing populist parties were the ones that disproportionately benefit from crises. Populists often blamed specific groups, such as immigrants or wealthy elites, for the economic woes, or/and promised to restore jobs and prosperity through policies that may not be feasible or sustainable (Moffit, 2015).

While populist movements can offer temporary relief for those affected by economic crises, there are concerns about the long-term consequences of populism since the economic policies of right-wing populists can be controversial and have been subject to criticism from economists and other commentators. Populist leaders often promote protectionist economic policies that can harm international trade and cooperation, leading to further economic uncertainty, while their proposed tax cuts may disproportionately benefit the wealthy. Additionally, some argue that anti-immigration policies can harm the economy by reducing the size of the labour force and limiting opportunities for growth. Classical macroeconomic populism – for instance – has typically been crisis-prone and ultimately unsustainable (Kaufman & Stallings, 1991). Furthermore, populist movements often promote simplistic solutions to complex problems, leading to policy decisions that may exacerbate economic crises rather than resolve them.

According to ‘relative deprivation’ theories, economic hardships are the main causes of populist attitudes (Guiso et al., 2017: 4). Poverty – exacerbated by a crisis – is often linked with support for authoritarianism. Neerdaels and his colleagues (2022) found that “shame and exclusion from society lead to increased support for authoritarianism […] because authoritarian leaders and regimes promise a sense of social re-inclusion through their emphasis on strong social cohesion and conformity” (Hedrih 2023). Consequently, alleviating economic hardships above a certain level is not always beneficial for populist political parties. In addition, authoritarian populist policies and capturing the media might have a higher explanatory power in how populist came in power during or after a crisis. Salgado et al. (2021) investigated the junction between populism and economic crisis (Euro Crisis) and hypothesized that media coverage and the communicative and rhetorical aspects of populism are the key reasons for its allure, not the level of how the economic crisis did impact national politics (Ibid: 574).

Economic crisis facilitates populism and reinforces the division between the winners and the losers of globalization (Kriesi & Pappas, 2015), however there are findings countering these statements (Lisi et al., 2019). Examination of populist rhetoric amid economic downturn (Ibid.) in the new democracies of Southern Europe (Greece, Portugal, Spain) has proved that the economic crisis has impacted the party system on all levels, but Lisi et al. (2019: 1288) also argues that “The key factors that are likely to favor the emergence or predominance of inclusionary rather than exclusionary populism in the aftermath of an economic crisis can be argued to lie in high levels of crisis intensity, in the retrenchment of welfare states in the face of economic crisis, and in the lack of partisan programmatic responsiveness. On the other hand, exclusionary populism, which is mostly associated with transformations taking place in the cultural and symbolic dimensions, is more likely to emerge when the salience of immigration increases, and mainstream right-wing parties do not politicize or give priority to xenophobic public preferences.”

Consequently, economic, and cultural crises “have a differential impact on the emergence and consolidation of populist parties – the former are more relevant for inclusionary populist parties, the latter are more conducive to the success of exclusionary populist parties” (Caiani & Graziano, 2019: 1153).

In conclusion, as Margalit (2019) contended, the economic-centric accounts are likely to overstate the role of economic insecurity as an explanation of the rise of populism. The author argues that the financial crisis contributed to the populist wave but views the crisis as more of a trigger than a root cause of widespread populist support. Similarly, while immigration is often a major concern of populist voters, treating it as an economic driver of populism is misguided (Hainmueller et al., 2015; Bansak et al., 2017; Hainmueller & Hopkins, 2014).

The rise of populism cannot be explained alone with the impact of the economic crisis. Other crises, namely political and cultural/moral, play a crucial role in the populist upswing as well. These crises reinforce and may interact with each other (Kriesi, 2018: 16). Caiani & Graziano (2019: 1141) found that “although the economic crisis has without any doubt provided a specific ‘window of opportunity’ for the emergence of new political actors, which have capitalized on citizens’ discontent, long-lasting political factors – such as the increasing distrust toward political institutions and parties – and the more recent cultural crisis connected with migration issues have offered further fertile ground for the consolidation of populist parties in several European countries.” The authors also posit that “the success of populist parties depend on the capacity to ‘politicize’ crises in terms of a need to rescue the ‘pure’ people from a greedy and corrupt elite” (Ibid., 2019: 1144).

In Greece, subsequent to the eruption of the economic crisis, both left-wing and right-wing populist parties could capitalize on the moment and increase their electoral support. Response to the economic crisis was expressed through the narratives of all political actors and observed across the party system. However, what happened in Athens in 2009, it was not only a crisis of economy, but overall, a crisis of democracy and political representation as well (Halikiopoulou, 2020). “This suggests that the rise of the Golden Dawn is closely related to the breakdown of political trust, good governance and the perceived efficacy of the state” (Ibid.).

As we can see, in identification of the relation between populism and economic crisis, one section of the literature aims to define populism and identify its causes, as well as models that explain how economic crises can fuel the rise of populist movements. Some of the most influential theories in this area include the concept of “populist mobilization” and the idea that economic crises create a “window of opportunity” for populist politicians to exploit. In contrast, others may examine the policy responses to economic crises and their impact on the development of populist movements by assessing the effectiveness of policy measures, such as austerity measures or stimulus programs, in addressing the root causes of the crisis and mitigating the rise of populism. Populist parties jumped to the front of the line to reject or shape the economic policies of neoliberalism. Ivaldi and Mazzeloni (2019: 202) noted that “the economic supply of radical right populist parties is best characterized by a mix of economic populism and sovereigntism.” This is exemplified by the unique political economic model of populists in power (See Poland, Hungary and Serbia).

Although the literature on the economic policies associated with contemporary populism (See Bartha et al., 2020; Markowski, 2019; Orenstein & Bugarič, 2020; Toplišek, 2020) is slowly growing; it is often discussed in the frame of causes of populist surge and does not dive deep into the new, viable illiberal economic policy model of populism, which may prove to be resilient in face of harsh economic environment (Feldmann & Popa, 2022: 236). The political economy of populism is described as the following by Orenstein and Bugaric who believe that populism arose due to both cultural and economic reasons, especially in Central- and Eastern European context: “After the global financial crisis, populist parties began to break from the (neo)liberal consensus, ‘thickening’ their populist agenda to include an economic program based on a conservative developmental statism” (Orenstein and Bugaric, 2020: 176). Feldmann and Popa’s research (2022) builds on the findings of this paper and calls for more research of the unorthodox economic model of populists.

Cultural Crisis

Cultural studies have been heavily influenced by the latest wave of populism (Moran & Littler, 2020). One major change in how we think about the intersection of culture, politics and economics occurred in 1992 when the publication of Jim McGuigan’s titled Cultural Populism came out. His book critically analyzed the ways in which popular culture functions as a source of resistance and as a means of ideological control, while he focused on (popular) culture (sport, television, film, pop music) outside of high culture (classical arts) – a popular instrument for authoritarian populism. He argued that cultural populism is a response to the growing sense of disaffection and frustration among people with the traditional political establishment, and that cultural populism offers a way for people to reclaim power and agency through cultural means. Valdivia (2020: 105) – in questioning of Mudde’s notion of populism – even states that “populism is a cultural narrative more than a thin-centered ideology.” In sum, cultural populism marks the emergence of a political frontier around cultural issues and crises.

The latter refers to a situation in which the values, norms, and beliefs of a society are being called into question. This can happen for a variety of reasons, such as rapid social or economic changes, the impact of globalization and technological advancement, immigration (the mixing of different cultures), or political upheaval, which can challenge established norms and ways of life or can lead to a sense of cultural displacement and loss of identity among certain groups of people. During a cultural crisis, the basic assumptions and shared understandings that hold a society together are called into question, leading to feelings of uncertainty and anxiety among members of the society. It can manifest in different ways, such as a loss of trust in institutions, a decline in traditional values, a rise in extremism, or a fragmentation of society, which can then lead to the rise of populism and new-old cultural values, which are “usually combining anti-elite and anti-immigrant nationalism with nationally and locally bounded demands for social justice” (Palonen et al., 2018: 12), as people may turn to leaders who promise to restore traditional values and return society to a perceived past golden era.

This idea is repeated in Inglehart and Norris’ (2016, 30) concept of ‘cultural backlash’ which argues that “the rise of populist political parties reflects, above all, a reaction against a wide range of rapid cultural changes that seem to be eroding the basic values and customs of Western societies.” In this idea, traditional cultural values and attitudes are making a comeback in response to the increasing secularization and liberalization of societies as people, who perceive their social status as declining, are pushing back against the changes and express support for more traditional, conservative cultural norms and values (Bornschier & Kriesi, 2013).

In the 21st century, one of the first elected political leaders who breached modern liberal democracy and created an authoritarian regime that enjoys popular support by making empty populist promises and exploiting the political short-sightedness of ordinary people was Vladimir Putin. Natalia Mamonova (2019: 591) argues that in rural Russia, the supporters of authoritarian populism, often referred to as ‘the silent majority’, does approve of the president and Putin’s traditionalist authoritarian leadership style appeals to this archetypal base of the rural society who creates the base of populist movement. The same has been observed in Hungary and Poland, although Tushnet and Bugaric (2022: 81) warns that in the case of Orbán and Kaczyński, their authoritarianism is more important than their populism.

Nonetheless, the social status of voters for candidates and causes of the populist right and left is under researched, although their motivations have similar cultural and economic roots (often a cultural or economic crisis). Some scholars and political analysts have argued that a cultural crisis, marked by the erosion of traditional values and a perceived loss of national identity, is one of the main drivers of populist movements in recent years, especially in Central- and Eastern-Europe (Orenstein & Bugaric, 2020; Krastev, 2017; Verovšek, 2020; Vachudova, 2020). Populist leaders often appeal to people’s sense of cultural nostalgia and offer a vision of a return to a simpler, more traditional way of life in these countries, but this rhetoric has been evident in Donald Trump speeches as well (whose populism is rather cultural than political) (Bonikowski & Stuhler, 2022; Brownstein, 2016; Elgenius & Rydgren, 2022; Goodheart, 2018).

According to Gidron and Hall (2017: 58), electoral support of populism has a common feature as a transnational phenomenon; “at its core lie key segments of the white male working class.” Support for populism is also stronger among the older generation, the less well-off, and women: essentially among citizens whose social status has been depressed by the economic and cultural developments following the fall of the Soviet Union. These changes are intertwined: people who see themselves as economically underprivileged, see their social status declining also tend to feel culturally-distant from the dominant groups in society (Ibid: 59-60). They likewise lean “to envision that distance in oppositional terms, which lend themselves to quintessential populist appeals to a relatively ‘pure’ people pitted against a corrupt or incompetent political elite.” Threats to a person’s social status evoke feelings of hostility to outgroups, especially if the latter can be associated with the threat of status. Populism grabs the essence of this threat and politicizes social status.

Social status was identified by German sociologist Max Weber (1968) as a distinctive feature of stratification in all societies, which is not synonymous with occupation or social class. It can be rather understood as a person’s position within a hierarchy of social prestige. A person’s objective social status depends on “widely shared beliefs about the social categories or “types” of people that are ranked by society as more esteemed and respected compared to others” (Ridgeway, 2014: 3). Concerns about subjective social status condition political preferences and play a role in political dynamics. Gideon and Hall’s (2017: 63) research proves how status concerns impinge on the decision to support one candidate or cause: “Just as citizens may vote for a party because they believe it will improve their material conditions, so they might support one because they believe it will improve their social status, either by altering socioeconomic conditions in ways that augur well for their social status or by promoting symbolic representations that enhance the status of the groups to which they belong.”

Even more, in many cases, populists do not need to substantially improve the material conditions or the social status of their electorate, it is sufficient to pit against and sustain hostility to outgroups and associate them with the threat of social status decline. The outgroups are clearly identified both by the European far right and cultural populists: the liberal world order, the “loose consensus” of parliamentary democracy, the supranational construction of EU, and “what they call cultural Marxism, that is individualism and the promotion of feminism and minority rights” (Laruelle, 2020). Furthermore, most scholar agrees on that cultural populism has more in common than just these well-identified enemies: “a coercive, disciplinary state, a rhetoric of national interests, populist unity between ‘the people’ and an authoritarian leader, nostalgia for ‘past glories’ and confrontations with ‘Others’ at home and/or abroad” (Mamonova, 2019: 562) In the case of cultural populism, the ‘Others’ include immigrants, criminals, ethnic and religious minorities, LQBTQ communities, feminists and cosmopolitan elites, whose subjective social status has increased in the last twenty years. This does not need to contribute to a decline in the subjective social status of the native members of the nation-state who are claimed to be the ‘true people’. However, because social status is based on a rank ordering, “it is somewhat like a positional good, in the sense that, when many others acquire more status, the value of one’s own status may decline” (Gidron & Hall, 2017: 68). The subjective social status of many men and women (without tertiary education, living outside big cities), rural dwellers and older generations is dependent on the belief that they are socially superior to the ‘Others’.

Regional decline seems closely coupled to cultural resentment. “The cultural trends that have raised the social prestige associated with urban life and working women have drawn firms offering good jobs and social care packages while seeking away employees from smaller cities and the countryside, intensifying the regional economic disparities that may feed cultural resentment and support for right populism” (Ibid: 78; Pfau-Effinger, 2004). The weakness of support for right populism in large metropolitan centers may reflect, not only relative prosperity, but the extent to which the experience of life within big cities promotes distinctive cultural outlooks” as the electoral results of the 2018 Polish local, the 2019 Hungarian local, the 2019 Turkish local, or the 2020 Russian regional elections shows (Ibid: 60).

All in all, socio-economic power structure in the countryside and the perceived social status of rural men and women largely defines the political posture of different rural groups. “Less secure socio-economic strata respond more strongly to material incentives, while better-off villagers tend to support the regime’s ideological appeals – often out of fear for their social status” (Mamonova, 2019: 579).

Populism and cultural crises are closely related and can be interdependent (Aslanidis, 2021). In some cases, they are mutually reinforcing and can exacerbate each other, creating a cycle of cultural and political upheaval or even culture wars (see the Brazilian case by Dias, 2022). On the one hand, Brubaker (2017: 373) stresses that “crisis is not prior to and independent of populist politics; it is a central part of populist politics.” Populism as a strong social force can contribute to a cultural crisis by challenging and undermining established values, norms, and institutions (Maher et al., 2022). Populist leaders and movements may use their power to reshape the cultural and political landscape, often in a way that promotes their agenda and ideology, which can contribute to a cultural crisis (Stavrakakis et al., 2018). This might be done by changing laws, policies, and institutions, and by promoting certain ideologies and narratives. On the other hand, some believe populism is a response to multiple major forms of crisis (see the division of present paper); as reported by Inglehart and Norris (2016), institutional distrust stemming from the economic crisis (Algan et al., 2017: 316) gives rise to populism.

Populist leaders and movements often present themselves as outsiders and can be critical of the status quo (anti-elitism), which can lead to a sense of uncertainty and disorientation among members of society. Additionally, populist movements can also polarize societies, by promoting nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment, which can lead to a fragmentation of society and a rise of nativism (Brubaker, 2017). Right-wing populism is more likely to divide insiders-outsiders based on cultural differences by emphasizing the outsiderhood of cultural elites (Ibid, 364). According to Kyle and Gultchin (2018: 12-13), this polarization is the 3rd strategy of populists to stoke insider-outsider division. Sharp division is exacerbated, dramatized and exaggerated by “a rhetoric of crisis that elevates the conflict between insiders and outsiders to a matter of national urgency.” Rhetoric of crisis (Moffitt, 2016) spans from populist protectionism – one of the five elements of populist repertoire – which includes cultural protectionism where populists highlight “threats to the familiar life world from outsiders who differ in religion, language, food, dress, bodily behavior, and modes of using public space” (Brubaker, 2017: 364).

Populists do love a ‘good crisis’: One of the most effective strategies of cultural populism is to perform a pervasive crisis dramatizing social division. “Populists are adept at linking failures in one policy area to failures in another, making them appear part of a broad and systematic chain of unfulfilled demands” (Kyle and Gultchin, 2018: 15). Immigrants, sexual minorities, women, religious and ethnic minorities all fall victim of this rhetoric. The changing theme of populist rhetoric is a common feature among long reigning populists in power. If they perform the same crisis, wage war against the same enemy for too long, they lose support, therefore, to maintain the fundamental crisis, they look for new ‘Others’. This however leads to deep social division as the circle of pure people is narrowing.

References

Adorno T., Frenkel-Brenswik E., Levinson D. J. and Sanford R. N. (2019). The Authoritarian Personality. Verso Books.

Ajzenman, N., Cavalcanti, T. and Da Mata, D. (2020). “More than Words: Leaders’ Speech and Risky Behavior During a Pandemic.” Cambridge Working Papers in Economics 2034. University of Cambridge.

Albertazzi, D., Favero, A., Hatakka, N. and Sijstermans, J. (2022). “Siding with the underdog: Explaining the populist radical right’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.” LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog. URL http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/114727/1/europpblog_2022_03_15_siding_with_the_underdog_explaining_the.pdf (accessed 1.25.23).

Algan, Y., Guriev, S., Papaioannou, E. and PassariI, E. (2017). “The European Trust Crisis and the Rise of Populism.”Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 309–382. http://www.jstor.org/stable/90019460