In this interview with the ECPS, Professor Nandini Sundar (Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University) delivers a stark assessment of India’s institutional trajectory under the BJP and its ideological parent, the RSS. Her central claim is unequivocal: “Almost every institution in this country has now collapsed, or has been subverted, in order to further the supremacist agenda.” She situates current developments within the longer history of Hindutva ideology, emphasizing the RSS’s founding goal of a Hindu supremacist state. Professor Sundar argues that a narrative of majoritarian victimhood underpins historical revisionism, institutional capture, and restrictions on academic freedom. She also highlights transnational pressures, noting that a “very active Hindutva diaspora” has targeted scholars abroad, constraining research and debate globally.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In this wide-ranging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Nandini Sundar— Professor of Sociology at the Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University, and one of India’s most prominent sociologists and a leading voice on democracy, violence, and state power—offers a stark assessment of the trajectory of Indian institutions under the rule of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its ideological parent, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Her central claim is unequivocal: “Almost every institution in this country has now collapsed, or has been subverted, in order to further the supremacist agenda.” Situating contemporary developments within the longer history of Hindutva ideology, Professor Sundar argues that the BJP cannot be understood apart from the RSS, “an unregistered, secretive organization” founded in 1925 “to establish a Hindu supremacist state in which all others would be second-class citizens.”

At the heart of this project, she explains, lies a powerful narrative of majoritarian victimhood. RSS discourse portrays Hindus as historical victims of “800 years of colonialism,” conflating Muslim rule with British imperialism and mobilizing a sense of lost civilizational pride. This paradox—an overwhelming majority imagining itself as dispossessed—underpins a wide array of policies, from historical revisionism to institutional capture. According to Professor Sundar, the claim to represent a wronged majority translates into concrete restrictions on academic freedom through ideological appointments, funding pressures, surveillance, and curricular transformation. Universities, in particular, have been reshaped to ensure that “only our narrative, only our voice, should count,” transforming spaces once associated with pluralism into arenas of political conformity and patronage.

The interview highlights how Hindutva governance operates not only through formal state mechanisms but also through diffuse networks of affiliated organizations and vigilante actors. Student groups such as the ABVP (the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad) and other RSS-linked formations function simultaneously as political mobilizers and instruments of intimidation, embedding campuses within what Professor Sundar calls a broader “ecosystem of vigilantism.” Meanwhile, democratic institutions—from courts to electoral bodies and media regulators—are portrayed as formally intact yet substantively hollowed out, enabling what she describes as the preservation of democratic form alongside the erosion of democratic substance.

Professor Sundar also draws attention to the transnational dimension of these dynamics. A “very active Hindutva diaspora,” she notes, has targeted scholars abroad, orchestrating harassment campaigns and reputational attacks that restrict academic inquiry on India globally. As a result, she warns, it has become “very difficult for anyone working on India to be able to research, write, and think freely, whether inside the country or outside the country.”

Taken together, her analysis presents Hindutva not merely as a domestic political ideology but as a comprehensive project of institutional transformation, cultural redefinition, and epistemic control. By foregrounding the links between majoritarian resentment, institutional subversion, and the policing of knowledge, this interview offers a sobering account of how democratic systems can be repurposed to sustain exclusionary rule while maintaining the appearance of constitutional continuity.

Here is the edited version of our interview with Professor Nandini Sundar, revised slightly to improve clarity and flow.

The BJP Cannot Be Understood Apart from the RSS and Its Supremacist Project

celebration of VHP – a Hindu nationalist organization on December 20, 2014 in Kolkata, India. Photo: Arindam Banerjee.

Professor Nandini Sundar, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: In your recent work on majoritarian resentment and the inversion of victimhood, how do you conceptualize the BJP’s claim to represent a historically wronged “majority,” and how does that claim translate into concrete restrictions on academic freedom (appointments, funding, policing, curricula)?

Professor Nandini Sundar: The BJP was founded by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an unregistered, secretive organization that has proliferated into many different fronts—education, labor, and virtually every sector, each with its own affiliated bodies. The BJP is the political wing of the RSS, which was founded exactly 100 years ago, in 1925, to establish a Hindu supremacist state in which all others would be second-class citizens.

If you look at RSS literature, it consistently portrays Hindus as victims suffering from what they call 800 years of colonialism, because they conflate periods of Muslim rule with British colonialism. This reflects a deep sense that India was ruled by Muslim rulers for many centuries and that a lost Hindu pride must now be regained. The past they invoke—often framed as a glorious Vedic age—overlooks the fact that ancient India consisted of many different communities practicing a variety of religions, rather than a unified “Hindu” civilization.

This constructed sense of victimhood, despite Hindus being the overwhelming majority—over 80 percent of the population—translates into efforts to rewrite history, for example by erasing the Mughal period. Yet it is impossible to understand India without considering the Mughal era or the various sultanates that existed from the 12th to the 18th centuries.

It also manifests in demographic anxieties, such as claims that Hindus are being overtaken by Muslims due to allegedly higher Muslim fertility rates—claims that are not supported by empirical evidence, since fertility rates among Muslims have declined sharply and vary across regions. In short, historical narratives, demographic fears, and broader perceptions of victimhood are mobilized together.

As noted, this translates first into historical revisionism. Second, in universities, vacancies have been systematically filled with individuals aligned with their ideology. This is not simply a matter of feeling victimized, because in the past, although the system was not always perfect, there was at least a perception that appointments were based on merit. If their candidates were not selected, it was often due to a lack of scholarly expertise rather than ideological exclusion.

Now, victimhood is invoked to claim that “our people” were neglected while positions were monopolized by the left. In reality, universities have been systematically reshaped to reflect their ideological preferences, and this has also become a source of patronage for their cadre.

Taken together, these developments reveal not only a discourse of victimhood but also a broader assertion of dominance—the belief that they are now the only legitimate force, and that only their narrative and voice should prevail.

Democratic Institutions Have Been Hollowed Out from Within

In “Inside Modi’s Assault on Academic Freedom,” you trace how formally democratic institutions can be repurposed to discipline dissent. What are the key mechanisms—legal, bureaucratic, and vigilante—through which democratic form is preserved while democratic substance is hollowed out?

Professor Nandini Sundar: Almost every institution in this country has now collapsed, or has been subverted, in order to further the supremacist agenda. If you look at the judiciary—take the Supreme Court, for instance—we have had several BJP chief ministers issuing hate speeches. There was a recent incident involving the chief minister of Assam, which has quite a sizable Muslim minority, putting out a video of him shooting Muslims with a gun, targeting them so that you could see Muslims in the viewfinder being shot at. People took this to the Supreme Court, and the Court refused to intervene, saying that you are only targeting BJP chief ministers, and has basically refused to do anything about hate speech coming from the highest constitutional authorities. If you look at any number of judicial pronouncements in the last decade and a half, they have consistently favored the BJP.

If you look at the Election Commission, which again has been packed with chosen bureaucrats, right now they are conducting a massive exercise across the country to register voters. Historically, everybody who has been living here has been considered a voter, apart from immigrants or others. The onus used to be on the state to find and register voters. Now the onus is on voters to prove that they are citizens of this country and produce birth certificates of their parents, grandparents, their own exam mark sheets, and a whole range of certificates to show that they are indeed genuine citizens. That has led to the disenfranchisement of large numbers—hundreds of thousands of people in each state. For example, about 600,000 in one state. It is just ridiculous, because these are all actual, genuine voters who have not been able to produce the right certificates, often because they are poor, or especially women who migrate. So, you can see that elections, too, are completely controlled by the BJP.

When it comes to the media, if you look at the Modi government’s spending on advertisements, the amount that goes to favored media, and the way that media critical of the government has repeatedly had court cases slapped on them, with independent journalists arrested—every field is under attack. Universities are one major field—higher education in particular, but education more generally—where the BJP and the RSS have been attacking all conventions, all democratic procedures, and installing their own people.

Precarity in Universities Is Undermining Academic Freedom

How do budget cuts, contractualization, and precaritization in higher education function as governance tools—producing compliance not only through ideology, but also through material dependence and career risk?

Professor Nandini Sundar: There’s been a change in the way universities are funded. Many university colleges are being asked to go autonomous, which means that they will be responsible for raising their own funding. This increases fees for students, and at the same time, minority students—say Muslims and Christians who were receiving fellowships—have seen those fellowships cut down. So, there has been a general reduction in student fellowships.

In terms of faculty recruitment, we see that even earlier there were a number of precarious positions—contractual teachers—and that still continues quite widely across private colleges. Precarious teachers, those without fixed contracts, obviously find it hard to be critical of anything that is going on and hard to teach freely. But you also see that now, whenever the precarity issue among teachers has been addressed, those positions have been filled with their own people.

So, in either situation, both among students and among faculty, contractualization and the reduction of fellowships are making it difficult for there to be a strong autonomous voice from students and faculty.

Terror Laws Are Weaponized Against Democratic Protest

Many accounts emphasize arrests, sedition/terror charges, and prolonged pre-trial detention. Analytically, how should we understand “process as punishment” as a populist-authoritarian technique of rule in India?

Professor Nandini Sundar: Absolutely. The whole judicial system is designed for process without punishment. If you take the case of Sharjeel Imam and Umar Khalid, two student leaders who have been arrested for over five years now without the case even coming to trial. The charges relate to their involvement in a movement for equal citizenship. In 2019, the government passed an act that would grant citizenship to refugees from every other country except Pakistan and Bangladesh, and to every other religion except Islam. This was also seen as the first step toward disenfranchising Indian Muslims, and there was a massive protest against it—a huge, peaceful, democratic protest, predominantly led by women in many parts of the country, but especially in Delhi.

These students, both from JNU (Jawaharlal Nehru University) and from Jamia (Jamia Millia Islamia), were involved in this democratic protest, and it was actually a very powerful democratic moment in this country’s history. But many students—predominantly Muslim students—were arrested. There were many people who took part in that protest, Muslims and Hindus, but only the Muslim students were arrested, and they have been in jail for the last five years. We have recorded speeches from them talking about the need for unity, upholding the Constitution, and love, yet they have been accused under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, which deals with terror.

They have been accused of terror conspiracies, which is completely ludicrous. The case has not even come to trial, and the evidence against them is completely flimsy. But everyone knows that they are being kept in jail because they are articulate student leaders who had a democratic vision for this country.

Campuses Are Embedded in a Wider Ecosystem of Vigilantism

How do you interpret the role of affiliated organizations (student wings, vigilante groups, informal “sentiment” enforcers) in expanding state capacity to intimidate universities while maintaining deniable distance?

Professor Nandini Sundar: The RSS has the biggest student wing in the whole country, the ABVP, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, which has been engaged in a number of attacks on other student organizations. It has also attacked various seminars that have gone against BJP ideology. It functions both as a student wing—providing the kind of membership and mobilization for ordinary student activities that any student organization does—and as a vigilante force.

There are also a number of other fronts of the RSS—the Bajrang Dal, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, and various other wings—which intimidate students and faculty on campuses. This is part of a more generalized surge in vigilantism, as vigilantes have been attacking Muslim traders, Muslims transporting cattle across state boundaries, Muslim shopkeepers, and Christian pastors. There is a whole range of vigilante forces that the RSS tacitly supports and grants immunity and impunity. So, the university is not free of this; it is completely embedded in that wider ecosystem of vigilantism.

Universities Modeling Diversity Became Central Adversaries

Why do institutions like JNU become such central targets in majoritarian projects? Is it their historical role in mass politics, their social composition, their epistemic authority—or the way they model pluralism?

Professor Nandini Sundar: All of the above, I should say. Many universities in India were set up as part of a nationalist project. For instance, Jamia, which was established before independence, was founded by nationalist leaders to provide an alternative form of education to the British colonial model, and it has had a very long, rich tradition of scholarship and student mobilization.

JNU was set up in the 1970s on a very distinct model of higher education, where the effort was to bring in students from all across the country, especially from underserved regions. It had an extremely interesting system of deprivation points, whereby students from backward regions would receive extra marks in addition to whatever they obtained in the entrance test. In this way, it managed to achieve a real plurality of students from across the country. They also had excellent faculty, and some departments were truly the best in the country, known for their academic excellence. Even today, it remains one of the strongest universities academically in India.

Partly because of this academic excellence and the pluralism of its students, JNU also developed a very strong left tradition. It is one place where left student unions have consistently won student elections, and it has had a distinctive style of politics in which debates on a wide range of national issues would continue late into the night, alongside campus concerns such as hostel bills, food, accommodation, and fees. So, it has been a very unusual kind of university, an iconic institution for liberal-left education, and that was something the BJP felt it had to attack and destroy.

Rewriting the Past to Control the Nation’s Narrative

How do textbook “rationalization” and selective historical erasure operate as a struggle over national temporality—who gets to narrate the past, and who is authorized to speak for the nation?

Professor Nandini Sundar: The RSS thinks that it is authorized to speak for the nation, and since it has control over the government and textbooks—because under the Indian system education is a matter both for the central (federal) government and for the states—there are also some boards that operate nationally, in addition to the state boards. So, the major producer of textbooks in India is the NCERT, the National Council of Educational Research and Training, which produces textbooks that are then used by these different boards or even used by state boards as models.

What the BJP has been doing is systematically changing these NCERT textbooks. For instance, removing references to caste, removing all traces of Mughal history from middle school textbooks, and giving more space to certain false narratives that promote Hindu rulers at the expense of others. So, it has huge power. I mean, the central government has enormous power to rewrite historical narratives. It is also, if you look at other fields—archaeology, for instance—it underplays the contributions of the South in historical research.

I don’t know how to put it, but it is enormously powerful in rewriting history and rewriting sociology, rewriting politics—everything, really.

National Security as a Catch-All Tool of Suppression

The state’s framing of “internal affairs,” “sensitive issues,” and “national security” often appears deliberately expansive. What does this elasticity reveal about authoritarian boundary-making in the knowledge sphere?

Professor Nandini Sundar: It also reveals something about authoritarian fragility. Just to give you a very recent example. The Wire, which is a news portal, ran a 52-second clip showing Prime Minister Modi running away from Parliament. This was during a debate in Parliament about how he had not taken a resolute stand when the Chinese were coming into India in 2020, and then he claimed that women MPs were threatening to bite him, and that’s why he didn’t attend Parliament. So, this was just a somewhat humorous video about how Modi was supposedly scared of being bitten by women MPs. The Wire’s Instagram page was shut down, there was a privilege motion against them from Parliament, and it was described as a national security issue. Now, there was nothing remotely related to national security about a small cartoon of Modi running away from women MPs.

But anything and everything can be described as a national security issue. People are being arrested, especially journalists in Kashmir, or students in Kashmir, who are really living under a state of terror. It is such a loosely applied concept, and the problem is that the law puts the onus squarely on the person who is accused under such laws. It is very hard to get bail under UAPA (Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act), which is why people like Umar and Sharjeel and other human rights activists in what is called the BK16 case (the 16 individuals locked up without a trial in the Bhima Koregaon case. S.G.), or across the country more generally, are finding it very difficult to get out of this, because they are accused under national security acts.

So, it is a very expansive definition. It is very, very open to abuse, and these laws should have no place in any democracy.

Food, Caste, and Control under Hindutva Governance

Beyond overt ideological control, what is the relationship between Hindutva governance and everyday disciplinary practices (food regimes, hostel rules, policing intimacy), and how do these practices intersect with gendered and caste-based hierarchies?

Professor Nandini Sundar: One of the things that the RSS, the Hindutva regime, has been trying to promote is the idea that India is a vegetarian country, and that people who eat meat are in some way inferior or should not be eating meat. They have been trying to associate that with Muslims and use it to target Muslims or Dalits, who were formerly called untouchables and who are still treated very badly and exploited by the system.

In fact, about 80% of India is non-vegetarian. But this has become a big issue in certain hostels. For instance, some of the Indian Institutes of Technology have had separate messes in hostels for vegetarians and non-vegetarians. In the past, people were free to eat whatever they wanted, and they could sit together and eat, but this kind of segregation creates a hierarchical divide in which those who eat pure vegetarian food are seen as somehow superior, because historically it has also been a caste issue.

There have been student movements against this segregation and hierarchy, but they have again been suppressed by the administration. A lot of what the Hindutva regime is doing is feeding into existing caste and religious prejudices, aggravating them, and creating a hierarchy in which Hindu upper-caste voices are seen as representing the whole nation.

Just another example: for some strange reason—because it is inconceivable that this government would do anything that progressive—the University Grants Commission (UGC), which governs the higher education space, issued rules mandating equity for students from historically discriminated backgrounds, such as Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, minorities, and OBCs (The Other Backward Classes). There was a huge protest against this by upper-caste students, who have been coming out on the streets saying that they are under threat and in danger from this equity movement. The Supreme Court has stayed the equity regulations, and the BJP government is really happy, because it has got the Supreme Court to do so. On the one hand, they put out these UGC equity regulations, but they actually did not want to implement them; their constituency of upper-caste people is against it, and fortunately for them, it has been stayed by the Supreme Court.

So, there is a very neat dovetailing between Hindutva upper-caste ideology and the various practices of this government.

Masculinist Power and the Politics of ‘Teaching a Lesson’

How do masculinist styles of leadership and majoritarian “strength” narratives shape state behavior toward universities—especially in the public performance of punishment, humiliation, and “teaching a lesson”?

Professor Nandini Sundar: It is a very masculinist ideology, and historically the RSS did not have room for women as part of its cadre; there was a separate women’s wing.

If you look at the state of Kashmir, for instance, and education in Kashmir—higher education in particular—the entire process has been about this. In 2019, the state of Jammu and Kashmir was stripped of its constitutional autonomy and reduced from a state to a union territory. The whole thing was couched in terms of teaching them a lesson, because it was seen as a source of terrorism, since it is the only Muslim-majority state in India, and there was a conscious effort to show them their place.

When it comes to universities, Kashmiri students in different parts of the country have been especially targeted and victimized, and again this is very much part of showing Muslims their place, showing Kashmiris their place in India. When it comes to women, there are many more subtle ways in which women have been affected. If you look at the entrance exams, thanks to a new system of multiple-choice entrance exams, the number of women entering colleges has dramatically declined. Even if the government officially says that its policy is inclusive of women studying, in fact many of its practical policies discriminate against women.

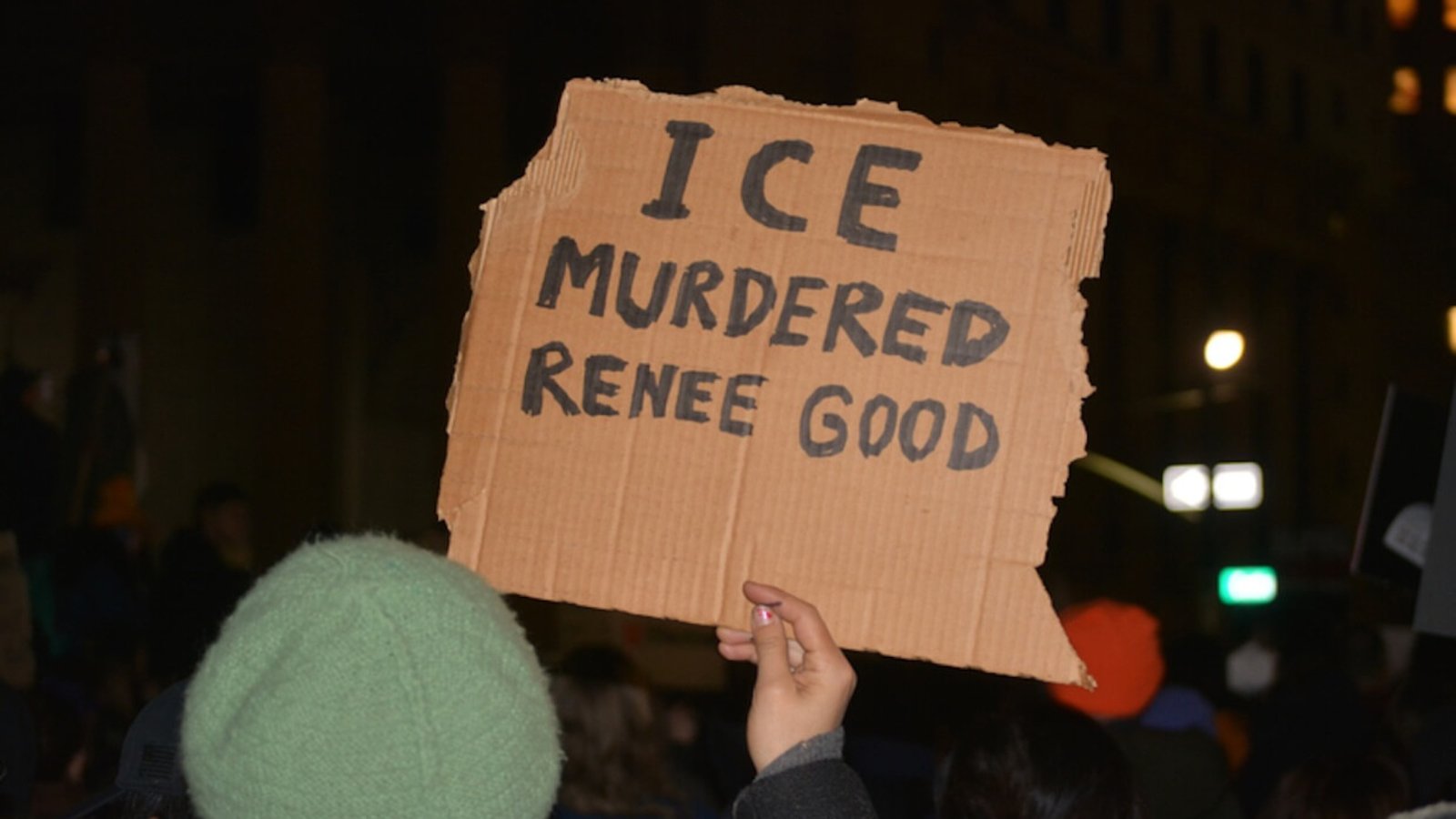

Targeting Scholars Abroad: Hindutva’s Reach Beyond India

To what extent do you see an externalization of repression—through harassment campaigns, institutional pressure, and reputational attacks—aimed at shaping scholarship on India outside India?

Professor Nandini Sundar: There’s a very active Hindutva diaspora that has been targeting academics who work on India in the US, the UK, and Europe. There was this conference called Dismantling Hindutva some years ago, where the active Hindutva diaspora went after the organizers of the conference. They flooded universities with so much hate mail against faculty members who were part of this conference that some of their servers collapsed.

It is really an organized, very virulent Hindutva diaspora, especially in the US, which has links with Zionists and follows the same sorts of procedures as some of the American far right. Unfortunately for them, the American far right, because they are Christian fundamentalists, has no regard for Hindu fundamentalists, so they are not really sure where they stand now. But they are just a very vicious, virulent lot when it comes to attacking people who are working on India.

For instance, there is an American historian called Audrey Truschke, who writes on Aurangzeb, the last Mughal emperor, and she has been relentlessly attacked. One could name various other people who have been singled out and attacked. The Indian government has also denied visas to a lot of academics working on India. This is really kind of inexplicable, because some of these academics have hugely contributed to the understanding of subjects the government itself promotes. For instance, there is a historian who works on Hindi. Now, the BJP government is insistent that everybody in the country should speak Hindi, that everybody should replace their own languages and know Hindi, yet this historian, who has contributed greatly to the understanding and study of Hindi, was denied a visa. There is absolutely no sense in this, even from their own perspective, because it is not like she was studying anything they would consider anti-national; she was studying Hindi literature.

So, it has become very difficult for anyone working on India to be able to research, write, and think freely, whether inside the country or outside the country.

Recasting the Past for Power

How has the language of decolonization and cultural authenticity been retooled to delegitimate critique—both within India and in global academia—while recoding censorship as civilizational self-defense?

Professor Nandini Sundar: That’s a really good question, because if you look at some of these Hindutva ideologues, they’ve adopted the language of decoloniality to claim that whatever has been done in Indian history, for instance, is colonial because it does not go back to ancient Hindu roots or does not adopt an Indic perspective.

In fact, the BJP or the RSS version of history is itself following a completely colonial template. They have adopted a periodization of Indian history based on Hindu, Muslim, and British India, which is a colonial construct, and that is what they have been following in the name of decolonization.

If you look at one major thrust of their programs, it has been to develop what they call Indic knowledge systems. By Indic knowledge systems, they basically mean Hindu and Vedic knowledge systems. This is something they have been pushing in every syllabus revision process, along with organizing a wide variety of seminars on Indic or Indigenous knowledge systems.

They have actually ignored all the work that has been done over the years, because scholars have already been working on different versions of Indian history and Indian society from a variety of perspectives, many of them indigenous. So, to say that they are coming up with some new framework is actually reinventing the colonial wheel while at the same time claiming that they are adopting some kind of great decolonial epistemology.

A Global Crisis of Academic Freedom Requires Collective Resistance

And lastly, Professor Sundar, given the risks of speaking, organizing, and even researching “sensitive” themes, what forms of collective strategy (professional associations, transnational solidarity, union politics, legal defense infrastructures) do you see as most effective—and what ethical obligations do scholars outside India have in confronting these dynamics without reproducing paternalistic frames?

Professor Nandini Sundar: I don’t think it is about scholars outside India or inside India. I think that scholars across the world are now facing similar threats, whether in Turkey, the US, or Europe. We are all being censored. We are all facing the Palestinian exception—nobody can talk about Palestine or teach about Palestine, not just in the US but in Germany and everywhere.

So, I don’t think there are any easy answers as to what can be done. We are all facing similar kinds of issues, so we need to share across countries how people have dealt with this, and work out ways in which we can collectively keep the university going as a space for research and critical thinking, and above all for teaching freely.

And I have hope that students—not the ABVP type, but ordinary students—are keen and curious about what is actually happening in the world, and I have great hope that students will be the ones who keep the university going. That is something that I think we will all have to face collectively, together across the world.