Please cite as:

Yogo, Edouard Epiphane. (2025). “The Role of Populism in Redefining Citizenship and Social Inclusion for Migrants in Europe.” Populism & Politics (P&P). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). March 4, 2025. Doi: https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0048

Abstract

This research examines the influence of populism on the redefinition of citizenship and social inclusion for migrants in Europe. It explores how populist movements leverage anti-immigrant sentiments to shape political discourse, laws, and societal attitudes. The study combines qualitative interviews with policymakers, activists, and migrants, and quantitative data from national surveys to analyze changes in citizenship laws and social inclusion challenges. Through case studies, it highlights variations in populist influence across European countries. The research concludes with policy recommendations aimed at fostering a more inclusive European society amidst rising populism.

Keywords: Populism, citizenship, social inclusion, migration dynamics, European societies

By Edouard Epiphane Yogo*

Introduction

The rise of populism in Europe has become one of the most significant political phenomena of the 21st century, fundamentally altering the political landscape and reshaping discussions surrounding citizenship and social inclusion for migrants. According to Arzheimer & Carter (2006), populist movements have emerged across various European countries, characterized by their anti-elite sentiments and a rhetoric that often scapegoats immigrants and minorities for societal issues (Arzheimer & Carter, 2006). As these movements gain traction, they exploit and amplify anti-immigrant sentiments, influencing political discourse, legislation, and societal attitudes toward migrants. This dynamic presents a critical need to explore how populism is redefining citizenship and the concept of social inclusion within the broader context of migration (Muis & Immerzeel, 2017).

At the heart of this inquiry lies a fundamental question: How does populism redefine the essence of citizenship? This question invites us to consider the shifts in legal frameworks, societal norms, and public perceptions surrounding the rights and identities of migrants in Europe (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018). The changing landscape of citizenship laws particularly the principles of jus soli (right of the soil) and jus sanguinis (right of blood) illustrates how populist narratives can reshape notions of national belonging (Varga & Buzogany, 2020). Moreover, the impact of these changes on the social integration of migrants poses significant implications for the cohesiveness of European societies.

To investigate these pressing issues, this research adopts a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative interviews with policymakers, activists, and migrants with quantitative data derived from national surveys. This comprehensive analysis aims to uncover not only the changes in citizenship laws but also the challenges to social inclusion faced by migrants in various European contexts. By examining the intersection of populism and migration, the study seeks to illuminate how populist movements influence citizenship policies and shape societal attitudes toward migrants.

One of the central themes of this research is the influence of populist narratives on public perceptions of migrants. In today’s polarized political climate, media representations play a crucial role in shaping these perceptions (Giugni & Grasso, 2021). Populist leaders and parties often utilize rhetoric that stigmatizes migrants, framing them as threats to national security, cultural identity, and economic stability (Talani, 2021). Such narratives contribute to the development of negative stereotypes and social divisions, making it increasingly difficult for migrants to achieve social integration in education, employment, and healthcare (Scheiring et al., 2024).

The first section of the study will examine how populist narratives reinforce exclusive notions of citizenship. By analyzing the rhetoric employed by populist movements, the research will highlight the ways in which these narratives seek to define and limit national belonging. Furthermore, it will explore case studies of citizenship policy adjustments in select European countries, illustrating how populism has influenced legislative reforms aimed at restricting migrants’ rights and opportunities.

The second section will focus on the challenges to social inclusion for migrants under the influence of populism. By investigating the critical role of media in shaping public perceptions, the study will analyze the stigmatization of migrants and the resulting impacts on their ability to integrate into society. The research will delve into how negative portrayals in the media can lead to societal attitudes that hinder access to essential services, such as education, employment, and healthcare, ultimately affecting migrants’ social standing and quality of life.

In exploring the consequences of populist policies on social inclusion, the research will address the restrictive measures that impact integration efforts. These policies often prioritize the needs and rights of native citizens over those of migrants, resulting in systemic barriers that prevent meaningful social inclusion. The study will also incorporate case studies that illustrate the differentiated effects of populist policies based on varying economic and historical contexts across European countries. This analysis aims to demonstrate how local conditions shape the outcomes of populist approaches to social inclusion and migration dynamics.

To interpret these dynamics effectively, this research will utilize the phenomenological constructivism framework proposed by Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann (Berger & Luckmann, 2011). According to Berger and Luckmann (2011), this theoretical approach posits that social reality is constructed through human interactions and is deeply influenced by the contexts in which these interactions occur. By applying this framework, the study will explore how populist narratives and policies are socially constructed and how they influence perceptions of citizenship and social inclusion (Mudde, 2014). This perspective will allow us to examine the processes through which migrants are categorized, marginalized, and included or excluded from the social fabric of European societies.

Using Berger and Luckmann’s insights, the research, based on phenomenological constructivism, will analyze how societal constructs surrounding nationality and belonging are negotiated and redefined in the context of populism (Rannikmäe et al., 2021). It will facilitate a deeper understanding of the ways in which individual and collective identities are shaped by populist discourse, as well as the implications of these construct s for migrants’ experiences of citizenship and social integration. By situating our analysis within this theoretical framework, we aim to highlight the significance of social constructions in shaping the realities of migrants in Europe. In addition to phenomenological constructivism, this research will also employ François Thual’s geopolitical method to provide a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between populism, citizenship, and social inclusion (Rannikmäe et al., 2021). Thual’s approach emphasizes the importance of contextual factors such as geography, history, and socio-political dynamics in shaping political behavior and policy decisions. This method allows us to analyze how populist movements are not only a response to immediate political conditions but are also deeply rooted in historical and geographical contexts that influence their evolution and impact (Thual, 1996).

Thual’s geopolitical method will guide the exploration of how different European countries experience and respond to populism in distinct ways (Loyer, 2019). By examining the geographical and historical backgrounds of specific case studies, we can uncover the localized factors that drive populist sentiments and how these sentiments manifest in citizenship laws and social inclusion policies (Zajec, 2018). This analytical lens will enhance our understanding of why certain countries adopt more restrictive policies while others may strive for inclusivity in the face of populism.

As the research unfolds, it will emphasize the need for inclusive policies that can counteract the negative effects of populism on citizenship and social inclusion. By synthesizing the findings, the study will conclude with policy recommendations aimed at fostering a more inclusive European society in the face of rising populism. These recommendations will focus on strategies that promote equitable access to rights and opportunities for migrants, thereby enhancing social cohesion and countering the divisive narratives propagated by populist movements.

In summary, this research seeks to illuminate the complex interplay between populism, citizenship, and social inclusion for migrants in Europe. By examining the influence of populist narratives on public perceptions and legislative reforms, the study will provide valuable insights into the challenges migrants face in achieving social integration. Ultimately, the findings will underscore the importance of developing inclusive policies that address the needs and rights of all members of society, fostering a more equitable and cohesive European community amidst the challenges posed by populism.

The Impact of Populism on the Redefinition of Citizenship

In the current global landscape shaped by the rise of populism, discussions around citizenship and national identity have gained renewed significance. Recent changes in citizenship laws reflect the increasing influence of populist movements that seek to redefine national belonging. This document will examine two key aspects: Changes in citizenship laws and principles under populist influence (A) and the relationship between populism and the concept of national identity (B), highlighting the tensions and redefinitions that arise.

Changes in Citizenship Laws and Principles Under Populist Influence

Discussing on changes in citizenship laws and principles leads us to examine two key areas. Firstly, the shifts in jus soliand jus sanguinis citizenship principles (1) and secondly, the influence of populist discourse on recent legislative reforms (2).

Analysis of Shifts in Jus Soli and Jus Sanguinis under Populist Influence

The principles of jus soli (right of the soil) and jus sanguinis (right of blood) are long-established frameworks that define how individuals acquire nationality (Retailleau, 2024). Jus soli grants citizenship to those born within a country’s territory, promoting inclusion and diversity, while jus sanguinis bases citizenship on parentage, linking it to lineage and heritage. Many countries have historically blended both principles to accommodate social and political contexts. However, the rise of populist movements has altered how these principles are applied, with significant implications for citizenship laws (El País, 2024).

Populism, characterized by its anti-immigration and nationalist rhetoric, has shifted the conversation toward more restrictive definitions of citizenship, often challenging jus soli by framing it as too inclusive (Giugni & Grasso, 2021; Le Monde, 2024). Populist leaders argue that automatic birthright citizenship allows individuals with no cultural or historical ties to the nation to gain full membership. For example, in the United States, under the Trump administration, jus solicame under scrutiny, with arguments about “anchor babies” used to portray birthright citizenship as a loophole exploited by immigrants (Schmidt, 2019).

Similarly, in Europe, populist movements have pushed for limiting or abolishing jus soli to preserve national identity. Germany, for instance, had integrated jus soli to respond to globalization, but recent populist pressures aim to reverse these changes.

While jus soli face restrictions, populist leaders have embraced jus sanguinis. This principle aligns with their focus on ethnicity, heritage, and national purity, promoting a more exclusionary form of citizenship based on ancestral ties (Le Monde, 2024). In Hungary, for instance, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s policies prioritize ethnic Hungarian identity, offering citizenship to ethnic Hungarians abroad while maintaining a rigid stance against immigrants and refugees. Likewise, Italy emphasizes jus sanguinis, granting citizenship to individuals of Italian descent but placing increasing scrutiny on migrants and refugees (Le Monde, 2024; Kymlicka, 2001).

The preference for jus sanguinis reflects a broader trend of ethno-nationalism under populist regimes. By favoring bloodline-based citizenship, populists create a narrower definition of national identity, excluding individuals without ancestral ties to the country (Joppke, 2010). This shift has serious consequences for social cohesion, as it marginalizes immigrants and minorities, potentially deepening societal divides.

The erosion of jus soli particularly affects children born to immigrant families, who may face statelessness or legal obstacles to full integration. Meanwhile, the reinforcement of jus sanguinis perpetuates exclusionary notions of citizenship, creating a tiered system where only those with ethnic or cultural ties to the state are considered full citizens (Le Monde, 2024). This dynamic threatens to alienate large segments of the population, especially in multicultural societies, contributing to increased social tensions.

The changes to jus soli and jus sanguinis driven by populist movements illustrate a shift toward restrictive and exclusionary citizenship policies. These alterations not only affect individuals directly impacted by more rigid laws but also have broader implications for the social and political stability of nations grappling with diversity and globalization (Giugni & Grasso, 2021). As populist ideologies continue to shape political discourse, the future of citizenship laws remains a contentious issue.

Influence of Populist Discourse on Legislative Reforms

Populism has significantly impacted global politics, shaping discourse and driving legislative reforms. Defined by its appeal to “the people” against perceived elites, populism thrives on nationalism, anti-globalization, anti-immigration, and protectionism (Destradi & Plagemann, 2019). Populist leaders push simplified solutions to complex issues, leaving lasting effects on policies related to immigration, citizenship, labor laws, and the judiciary.

Populism views politics as a battle between the “pure” people and the “corrupt” elites, positioning populist leaders as defenders of the common citizen against established institutions. Exploiting grievances over economic inequality, cultural alienation, or fears of losing national identity, populists advocate for radical reforms (Olivas Osuna, 2020). Their emotionally charged rhetoric resonates with voters who feel marginalized, fostering a political environment that supports swift, often divisive, legislative changes.

One of the most significant areas of populist influence is immigration and citizenship policy. Populists frame immigration as a threat to national identity and economic security, pushing for stricter controls. In the US, Donald Trump’s administration implemented controversial policies such as the Muslim Ban and attempted to end birthright citizenship (Inglehart, 2016). These moves, rooted in populist rhetoric, sought to restrict immigration and tighten borders, casting immigrants as burdens on the system. Similarly, in Europe, populist leaders like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán have championed anti-immigration laws, presenting migrants as threats to national security and Christian identity (Dahlgren, 2006). These legislative changes, shaped by populism, have led to a more hostile environment for migrants and refugees, contributing to growing xenophobia.

Economic protectionism is another key area influenced by populism. Populist leaders, responding to fears of globalization and job displacement, advocate for policies that protect domestic industries. Trump’s “America First” rhetoric resulted in tariffs aimed at protecting American jobs, leading to trade wars with countries like China (Jones, 2019). While these policies offered short-term relief to certain industries, they also raised consumer prices and strained international trade relations. In Europe, populist figures like Marine Le Pen in France and Matteo Salvini in Italy have similarly pushed for economic protectionism, though such policies often hinder long-term growth and international cooperation (Destradi & Plagemann, 2019).

Populists also target the judiciary, portraying it as an elitist institution disconnected from the people. This view justifies legislative reforms that increase executive control over the judiciary, undermining democratic checks and balances (Bauer & Becker, 2020). In Poland, the populist Law and Justice Party (PiS) introduced reforms giving the government greater control over judicial appointments, weakening judicial independence. Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan similarly used populist discourse to justify constitutional changes that consolidated executive power and diminished the judiciary’s role (Blokker, 2019). These reforms, driven by populist ideals, threaten democratic governance by reducing the separation of powers and weakening the rule of law.

Cultural nationalism is another area where populist discourse drives legislative changes. Populist leaders often promote national culture while resisting multiculturalism. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government enacted the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 2019, which grants citizenship to non-Muslim refugees, marginalizing Muslims and promoting Hindu nationalism (Adamidis, 2021). This, along with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), exemplifies how populist rhetoric can shape exclusionary legislative reforms, reshaping national identity along religious lines (Tushnet, 2020).

Populism’s influence on legislative reforms is profound, particularly in immigration, economics, judiciary control, and national identity. Although populists claim to represent the will of the people, their policies often lead to restrictive, exclusionary measures that challenge democratic principles (Löfflmann, 2022). As populism continues to grow, its influence on legislative processes will likely persist, raising concerns about the future of democratic governance and civil liberties worldwide.

Populism and the Concept of National Identity

This section delves into the relationship between populism and national identity, focusing on two critical aspects: The use of anti-immigrant rhetoric to reinforce exclusive notions of citizenship, highlighting how such discourse seeks to define and limit national belonging (1) and Case studies of citizenship policy adjustments in select European countries (2).

The Use of Anti-immigrant Rhetoric to Reinforce Exclusive Citizenship

Populist leaders frequently employ anti-immigrant rhetoric to portray immigrants as existential threats to a nation’s cultural, economic, and social fabric. This rhetoric becomes a powerful tool to shape national identity in exclusionary terms, typically casting immigrants as outsiders based on racial, ethnic, or religious differences (Muis & Immerzeel, 2017). Through this discourse, populist movements argue that immigrants dilute national culture, displace native workers, and strain public resources, all while posing threats to national security. By framing immigration in such stark terms, populist rhetoric fosters fear and division, creating a political climate in which restrictive and exclusionary citizenship policies can be justified (Mudde, 2014).

At the core of populist anti-immigrant rhetoric lies the concept of an “authentic” national identity one that is rooted in historical, cultural, and sometimes religious heritage. This identity is portrayed as under siege by foreign influences, particularly immigrants who are seen as incapable of integrating into the national fabric (Rannikmäe et al., 2021). Populist leaders often evoke a sense of nostalgia for a perceived golden age when national culture was more “pure” or homogeneous, untainted by external influences. This idealized past is contrasted with the present, where immigration is depicted as eroding the cultural unity and social cohesion of the nation (Talani, 2021). By appealing to this notion of cultural purity, populist leaders can present themselves as defenders of the nation’s true identity, rallying support from those who feel alienated or threatened by globalization and multiculturalism.

Immigrants, particularly those from non-Western or non-Christian backgrounds, are often depicted as fundamentally different from and incompatible with the values, traditions, and way of life of the host country (Giugni & Grasso, 2021). This portrayal not only amplifies existing prejudices but also legitimizes exclusionary policies. In many populist narratives, immigrants are scapegoated for a range of societal problems from unemployment and housing shortages to crime and the perceived decline of national values. This scapegoating simplifies complex socio-economic issues, presenting immigration as the primary cause of these challenges and offering a convenient target for public anger and frustration (Varga & Buzogany, 2020).

The distinction between “us” (native citizens) and “them” (immigrants) is a central feature of populist rhetoric. This binary division serves to reinforce a sense of national unity among the “native” population while casting immigrants as a threatening “other” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine, 2015). This division is often racialized, with immigrants from non-European or non-Christian backgrounds portrayed as more dangerous or culturally alien. In some cases, populists draw on religious differences, framing Muslim immigrants, for example, as a threat to secular or Christian values (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine, 2015).

These distinctions are used to justify policies that restrict immigrants’ access to citizenship, limit their rights, and reduce their opportunities for social and economic integration (Manatschal et al., 2020). One of the most prominent ways in which this rhetoric translates into policy is through reforms aimed at restricting immigration and tightening citizenship requirements. Populist leaders often advocate for measures that make it more difficult for immigrants to acquire legal status, obtain work permits, or access public services (Varga & Buzogany, 2020). In some cases, they push for the revocation of citizenship for naturalized immigrants who are deemed to have violated national norms or values. These policies are framed as necessary steps to protect the nation’s identity and security, resonating with voters who feel that their cultural heritage and economic opportunities are being undermined by immigration.

This anti-immigrant rhetoric also extends to asylum seekers and refugees, who are often portrayed as economic migrants in disguise, seeking to exploit the nation’s welfare system rather than fleeing genuine persecution (Talani, 2021). By blurring the lines between refugees and economic migrants, populist leaders erode public sympathy for those seeking asylum and create a narrative in which all forms of immigration are seen as illegitimate or dangerous. This narrative provides political cover for policies that deny refugees access to asylum processes, push them back at borders, or place them in detention centers with limited legal rights (Hammar, 1990).

Beyond shaping immigration and asylum policies, populist rhetoric also influences broader social attitudes. By constantly framing immigrants as threats to national security and culture, populist leaders normalize xenophobic and exclusionary attitudes (Löfflmann, 2022). This not only stokes fear and resentment among the native population but also creates an environment in which discrimination against immigrants and minorities is more likely to be tolerated or even encouraged. In some cases, this rhetoric has been linked to increases in hate crimes and other forms of violence against immigrant communities (Varga & Buzogany, 2020).

Moreover, populist anti-immigrant rhetoric undermines the principles of equality and inclusion that are foundational to democratic citizenship. By advocating for policies that exclude certain groups based on their race, religion, or ethnicity, populist leaders challenge the idea of universal citizenship and equal rights for all individuals within a nation (Giugni & Grasso, 2021). Instead, they promote a hierarchical vision of citizenship, where some individuals are deemed more deserving of rights and protections than others based on their cultural or ethnic background.

Anti-immigrant rhetoric serves as a key tool for populist leaders to shape national identity in exclusionary terms. By portraying immigrants as threats to culture, economy, and security, populists legitimize policies that restrict immigration, deny citizenship, and limit the rights of minorities (Talani, 2021). This rhetoric not only fuels fear and division but also reshapes public policy in ways that undermine the principles of equality and inclusion, leading to a more fragmented and polarized society. As populist movements continue to gain traction globally, the challenge of balancing national identity with inclusivity and tolerance remains a pressing issue for modern democracies (Muis & Immerzeel, 2017).

Case Studies of Citizenship Policy Adjustments in Select European Countries

Across Europe, populist movements have played a pivotal role in shaping national identity and citizenship policies, often pushing for more restrictive laws that make it harder for immigrants to gain citizenship or legal residency. This shift reflects the growing influence of populist rhetoric, which frames immigration as a threat to national culture and security. By examining the cases of Hungary, Italy, and France, it becomes evident how populist leaders have redefined national identity and driven legislative reforms that reflect exclusionary views of citizenship.

In Hungary, under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, the government has adopted a strongly anti-immigrant stance, particularly targeting Muslim-majority countries. Orbán’s administration has positioned itself as the defender of Hungary’s Christian identity, presenting immigration as an existential threat to the nation’s cultural and religious fabric (Varga & Buzogany, 2020). The construction of border fences to block refugees, along with Hungary’s refusal to participate in EU refugee resettlement programs, demonstrates the government’s commitment to preventing the settlement of immigrants (Palonen, 2018). This emphasis on exclusion is further reflected in the tightening of citizenship laws, which aim to maintain a homogenous national identity, rooted in ethnic and religious purity.

A key piece of legislation that encapsulates Hungary’s approach to immigration is the “Stop Soros” law, named after Hungarian-American philanthropist George Soros, who has supported pro-migrant policies (Hutter & Kriesi, 2019). The law criminalizes aid to asylum seekers and organizations working with immigrants, reinforcing the idea that immigrants are unwelcome in Hungary. Orbán’s government has used this law to portray immigrants as threats to the nation, while redefining Hungarian national identity along ethnically and religiously exclusionary lines. By positioning itself as the protector of a pure, Christian Hungary, the government has marginalized anyone perceived as foreign or different, particularly those from Muslim backgrounds (Pappas, 2019).

Italy, another example of populist influence on citizenship policies, has seen significant changes under the leadership of Matteo Salvini, head of the right-wing League party. Salvini, who served as Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister, built his political platform around the idea of protecting Italy’s national identity from the perceived dangers of immigration (Varshney, 2021). His “Italians First” campaign emphasized limiting immigration, particularly from Africa and the Middle East, as a way to safeguard Italy’s cultural and economic interests.

Salvini’s government enacted several legislative changes that made it harder for immigrants to gain legal residency and citizenship. For example, the “security decree” introduced during his tenure tightened residency requirements and made it easier for the government to revoke asylum status. These policies were framed as necessary for maintaining public safety and reducing the immigrant population (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2017). By casting immigrants as criminals or economic burdens, Salvini tapped into public anxieties about national identity and security, securing popular support for more restrictive immigration and citizenship laws. His efforts also extended to children born to foreign parents in Italy, for whom gaining citizenship became increasingly difficult under the new regulations.

France, under the influence of Marine Le Pen and her National Rally party, has similarly witnessed a rise in populist-driven immigration policies. Le Pen has long advocated for a reduction in immigration and the protection of French identity, positioning herself as a defender of the nation’s cultural heritage (Mayer, 2013). Her party has pushed for laws that would end birthright citizenship, making it harder for children born in France to immigrant parents to acquire citizenship (Soffer, 2022). This approach reflects a broader desire to redefine French citizenship in exclusive terms, prioritizing the interests of native-born citizens over those of immigrants.

Le Pen’s framing of national identity is closely tied to the preservation of France’s cultural and historical legacy, often in opposition to immigration from Muslim-majority countries. During her 2017 and 2022 presidential campaigns, Le Pen emphasized the need to protect French values from external influences, linking immigration to issues of national security, cultural erosion, and economic instability (Bonikowski et al., 2018). While she has not won the presidency, her influence has pushed mainstream political parties in France to adopt stricter stances on immigration and citizenship, showing the broader impact of her populist rhetoric.

In all three countries, populist leaders have successfully reshaped public discourse around immigration and citizenship, using anti-immigrant rhetoric to justify more restrictive policies. By framing immigrants as threats to national identity and security, they have fostered a climate of fear and division, where exclusionary measures are seen as necessary to protect the cultural and social fabric of the nation (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2017). This dynamic not only makes it more difficult for immigrants to integrate and gain citizenship but also redefines what it means to be a member of the nation, often in ways that marginalize racial, ethnic, and religious minorities.

Clearly, populist movements across Europe have significantly influenced citizenship policies by promoting exclusionary definitions of national identity. Whether in Hungary, Italy, or France, populist leaders have used anti-immigrant rhetoric to push for legislative reforms that limit immigration, restrict access to citizenship, and reinforce a narrow conception of national belonging. These changes reflect broader concerns about preserving cultural homogeneity in an increasingly globalized world, where immigration is often framed as a threat rather than a source of enrichment.

Challenges to Social Inclusion for Migrants Under Populism

In today’s polarized political climate, media representations play a crucial role in shaping public perceptions of migrants. These portrayals can significantly influence societal attitudes and policies. This study will explore two key areas: Media representations and public perceptions of migrants (A) and the consequences of populist policies on social inclusion (B), examining how these narratives and policies interact and impact marginalized communities.

Media Representations and Public Perceptions of Migrants

In this section, we investigate the critical role of media in shaping public perceptions of migrants. We focus on two key aspects: first, the influence of populist narratives on the stigmatization of migrants, examining how these narratives contribute to negative stereotypes and social divisions; and second, the impacts of these perceptions on social integration in education, employment, and healthcare, highlighting the challenges migrants face in accessing essential services and opportunities in society.

Influence of Populist Narratives on Migrant Stigmatization

Populist narratives have a powerful influence on the stigmatization of migrants, shaping public perceptions in ways that often fuel fear, division, and hostility. These narratives simplify complex social issues by framing migrants as threats to national identity, economic stability, and security, which amplifies existing societal tensions. In many countries, populist leaders use anti-immigrant rhetoric to galvanize political support, constructing migrants as scapegoats for various social and economic challenges (Abrajano & Hajnal, 2015). This stigmatization has far-reaching consequences, reinforcing negative stereotypes and shaping public policy in exclusionary ways.

At the heart of populist narratives is the concept of “otherness,” where migrants are depicted as fundamentally different from the native population. This otherness is often framed along ethnic, racial, or religious lines, with migrants presented as a homogeneous group that poses a threat to the nation’s cultural identity. In Europe, for instance, populist parties frequently depict Muslim migrants as unwilling or unable to assimilate into Western societies, associating them with extremism or radicalism (Hawley, 2016). This portrayal suggests that migrants are not merely different but incompatible with the nation’s values and way of life. Populist leaders, such as Marine Le Pen in France or Viktor Orbán in Hungary, leverage these fears of cultural erosion to rally support, positioning themselves as protectors of the nation’s authentic identity (Wojczewski, 2019).

Populist rhetoric often goes beyond cultural concerns to frame migrants as economic threats, claiming that they steal jobs, exploit social services, and drain public resources. This portrayal is particularly prevalent during economic downturns, when populist leaders can channel public anxieties about unemployment and financial insecurity into anti-immigrant sentiment (Steele & Homolar, 2019). Migrants are depicted as competitors for scarce resources, pitting them against native citizens in a zero-sum game where the prosperity of one group is seen as coming at the expense of the other. The media plays a significant role in perpetuating this narrative by sensationalizing stories of migrants benefiting from welfare or engaging in criminal activities, often without providing context or balance (Betz, 1994). This selective reporting reinforces the perception that migrants are a burden on society, even when evidence shows their positive contributions to the economy.

In addition to cultural and economic threats, populist narratives often link migrants to security risks, portraying them as potential criminals or terrorists. This is particularly pronounced in countries that have experienced terrorist attacks, where populist leaders frequently draw direct connections between immigration and security (Kubin & von Sikorski, 2021). By framing migrants as dangerous outsiders who pose a threat to national safety, populist leaders can justify restrictive immigration policies and securitization measures. In the United States, for example, President Donald Trump used rhetoric that depicted migrants (Becker, 2019), especially those from Latin America, as criminals and rapists, capitalizing on fears of crime to promote his anti-immigration agenda (Norris & Inglehart, 2019). This rhetoric resonates with portions of the electorate who are already concerned about safety and security, amplifying support for exclusionary policies.

Populist leaders skillfully use media platforms to spread these narratives, particularly in today’s highly polarized media landscape. Traditional news outlets, social media, and even political advertisements become conduits for anti-immigrant rhetoric, allowing populist leaders to reach broad audiences with messages that vilify migrants. In this environment, misinformation and sensationalism thrive (Kubin & von Sikorski, 2021). False or exaggerated stories about migrant crime rates, welfare fraud, or cultural clashes circulate widely, reinforcing negative perceptions of migrants. Social media, in particular, has proven to be a fertile ground for these narratives, where algorithms amplify divisive content and create echo chambers that reinforce preexisting biases (Gidron & Bonikowski, 2013).

The consequences of this stigmatization are profound and far-reaching. As populist narratives gain traction, public opinion shifts toward greater hostility and mistrust of migrants, making it easier for populist leaders to enact exclusionary policies. This shift in public sentiment often leads to increased support for policies that restrict immigration, limit access to citizenship, and curtail the rights of refugees and asylum seekers (Mudde, 2019). For example, in Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s government has passed a series of laws that severely limit immigration and criminalize activities that support asylum seekers, framing these measures as necessary to protect Hungary’s Christian identity. In Italy, Matteo Salvini’s anti-immigrant rhetoric helped fuel the passage of laws that tightened residency requirements and made it easier to revoke asylum statuses, reflecting a broader European trend of hardening immigration policies.

Beyond policy, the stigmatization of migrants has deep social consequences. It fosters an environment where xenophobia and discrimination become normalized, affecting the daily lives of migrants and their ability to integrate into society (Wodak, 2015). Migrants face prejudice in the workplace, in schools, and in public spaces, often experiencing social exclusion and hostility based on their perceived status as outsiders. This stigmatization also fuels tensions between native populations and migrant communities, deepening social divisions and undermining efforts toward inclusion and cohesion.

Impacts on Social Integration in Education, Employment, and Healthcare

The stigmatization of migrants, fueled by populist narratives, significantly impacts their social integration in key areas such as education, employment, and healthcare. These effects not only hinder the ability of migrants to contribute to society but also exacerbate social divisions, perpetuating cycles of marginalization and exclusion (Varga & Buzogany, 2020). By examining these three critical sectors, we can better understand how negative perceptions of migrants shape their experiences and opportunities in host countries.

In the realm of education, migrant children often face significant challenges that hinder their ability to integrate successfully. Populist rhetoric can create an environment of hostility in schools, where migrant students may be perceived as outsiders or even blamed for the struggles faced by the local population (Palonen, 2018). This stigma can lead to bullying, discrimination, and social isolation, significantly impacting the emotional and psychological well-being of these children (Hutter & Kriesi, 2019). Additionally, language barriers and differences in educational backgrounds can further complicate their integration. Schools may lack the necessary resources and training to support non-native speakers, resulting in disparities in academic achievement and engagement (Mayer, 2013). Consequently, many migrant children may fall behind their peers, limiting their educational opportunities and long-term prospects.

Furthermore, the negative perceptions of migrants can influence the attitudes of teachers and school administrators, leading to biased expectations and treatment. In environments where populist sentiments prevail, educators may unconsciously lower their expectations for migrant students, perpetuating a cycle of disadvantage (Soffer, 2022). This systemic bias can result in fewer opportunities for advanced coursework or extracurricular activities, limiting the social networks that are crucial for future success. As a result, the educational system, instead of serving as a vehicle for social mobility, can reinforce existing inequalities, ultimately affecting the broader societal fabric.

In the employment sector, stigmatization often manifests in barriers to job opportunities and professional advancement for migrants. Populist narratives typically portray migrants as competitors for jobs, leading to negative stereotypes that they are less qualified or less committed than native workers (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2017). This perception can result in discriminatory hiring practices, where employers may favor native candidates over equally qualified migrants. Studies have shown that migrants, particularly those from non-Western backgrounds, often face significant hurdles in securing employment, despite possessing relevant skills and qualifications (Pappas, 2019). They may be relegated to low-wage jobs or sectors characterized by high turnover and job insecurity, limiting their economic mobility and integration.

Moreover, even after securing employment, migrants may encounter challenges in the workplace stemming from stigma. They might face harassment, exclusion from social networks, or limited access to professional development opportunities (Giugni & Grasso, 2021). This can create a hostile work environment that not only affects job satisfaction but also impacts overall mental health and well-being. The lack of upward mobility can lead to a sense of disillusionment and alienation, reinforcing feelings of being an outsider in their host society (Kymlicka, 2001).

In terms of healthcare, the stigma surrounding migrants can create significant barriers to accessing essential services. Fear of discrimination or negative treatment can deter migrants from seeking medical care, even when needed (Goodman, 2010). Populist narratives often frame migrants as burdens on public health systems, perpetuating the idea that they are undeserving of resources and services. This perception can lead to healthcare providers exhibiting implicit biases, resulting in inadequate treatment or care (Joppke, 2010). Migrants may experience delays in receiving necessary medical attention, contributing to poorer health outcomes.

Additionally, cultural differences and language barriers can further complicate healthcare access for migrants. Many may struggle to navigate complex healthcare systems or communicate their needs effectively, leading to misunderstandings and misdiagnoses. In some cases, these barriers can prevent migrants from receiving preventive care, increasing their vulnerability to chronic health conditions and exacerbating existing health disparities.

The impact of these challenges extends beyond individual migrants; it affects families and communities as well. When migrants struggle to integrate into education, employment, and healthcare systems, it creates a cycle of disadvantage that can perpetuate intergenerational poverty and marginalization (Bauer & Becker, 2020). Children of migrants may inherit these challenges, facing compounded obstacles in their own efforts to integrate and succeed. This can lead to a lack of social cohesion, where communities become polarized along lines of nationality, ethnicity, or immigration status.

To end, the stigmatization of migrants, largely driven by populist narratives, has profound impacts on their social integration across education, employment, and healthcare sectors. These negative perceptions hinder the ability of migrants to access opportunities, contribute to society, and achieve their full potential. The consequences of this marginalization are far-reaching, not only affecting the lives of migrants but also undermining the social fabric of host communities. To foster greater social integration, it is essential to combat harmful stereotypes and promote inclusive policies that recognize and value the contributions of migrants. By addressing these barriers, societies can work towards a more equitable and cohesive future, benefiting everyone involved.

Consequences of Populist Policies on Social Inclusion

Exploring the consequences of populist policies on social inclusion compels us to understand the restrictive measures that impact inclusion and integration. Additionally, it invites us to examine case studies that illustrate the differentiated effects of these policies based on varying economic and historical contexts.

Restrictive Policies on Inclusion and Integration

The rise of populist movements across various countries has led to the implementation of restrictive policies that significantly impact social inclusion and integration, particularly for migrants and marginalized communities (Varshney, 2021). These policies are often framed as necessary measures to protect national identity, security, and the interests of the native population, but they frequently create barriers that hinder the full participation of individuals from diverse backgrounds in society.

One of the most significant aspects of restrictive policies is the tightening of immigration laws, which can result in limited pathways for legal residency and citizenship for migrants. Many populist governments have introduced measures that require higher income thresholds, extensive documentation, or language proficiency tests that disproportionately disadvantage less affluent or non-native speakers (Blokker, 2019). Such requirements not only exclude potential immigrants but also create an environment of uncertainty and fear among those already residing in the country (Adamidis, 2021). The fear of deportation or legal repercussions can deter migrants from seeking essential services, including healthcare, education, and employment, thereby exacerbating their marginalization.

Moreover, these policies often reinforce negative stereotypes about migrants, portraying them as potential threats to public safety or as burdens on social services. Populist rhetoric frequently capitalizes on economic anxieties by suggesting that migrants take jobs from locals or strain public resources (Tushnet, 2020). This narrative is particularly powerful during times of economic downturn, where competition for jobs and services is heightened. As a result, policies that restrict access to social benefits for migrants can lead to a situation where these individuals are excluded not only from economic opportunities but also from social protections that are essential for integration (Hammar, 1990).

In many countries, populist leaders have also targeted specific groups of migrants, often based on their nationality, ethnicity, or religion. For example, anti-immigrant laws may specifically affect those from predominantly Muslim countries or refugees fleeing conflict (Schmidt, 2019). This targeted exclusion fosters a climate of division, where certain communities are systematically marginalized. In schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods, this can lead to increased tension and hostility, making it challenging for migrants to form connections with the broader community and hindering their ability to integrate socially (Ruhs & Vargas-Silva, 2015).

Furthermore, restrictive policies on inclusion are often accompanied by a lack of investment in programs that promote social cohesion and integration. For instance, funding for language classes, job training, and cultural exchange initiatives may be cut or deprioritized in favor of enforcement mechanisms aimed at controlling immigration (Giugni & Grasso, 2021). This lack of support means that even those migrants who wish to integrate and contribute to their new communities face significant obstacles (Rannikmäe et al., 2021). The absence of inclusive policies sends a clear message that diversity is not welcomed, further entrenching social divisions.

In addition to impacting migrants, these restrictive policies can have broader societal implications. By promoting exclusion rather than inclusion, populist policies undermine the social contract that binds communities together (Bonikowski et al., 2018). This erosion of trust can lead to increased polarization within society, where divisions based on nationality, ethnicity, and class are exacerbated. The resultant societal fragmentation can hinder collective action and diminish the capacity for communities to address common challenges, ultimately impacting national cohesion and stability.

To counteract the negative impacts of these policies, it is crucial for governments and civil society to advocate for more inclusive approaches to social integration. This involves not only reforming immigration laws to create fair and accessible pathways to residency and citizenship but also investing in programs that promote understanding and collaboration among diverse communities (Manby, 2018). By fostering an environment of inclusivity, societies can harness the potential contributions of migrants and build resilient communities that thrive on diversity rather than fear.

Case Studies on Differentiated Effects Based on Economic and Historical Contexts

The consequences of populist policies on social inclusion are not uniform; they vary significantly based on the economic and historical contexts of different countries (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017). Examining case studies from diverse regions provides valuable insights into how populism shapes social inclusion and reveals the complexities of these dynamics.

One notable example is the case of Hungary under PM Orbán. Hungary’s historical context, shaped by its post-communist transition and ongoing struggles with national identity, has made it particularly susceptible to populist rhetoric (Norris & Inglehart, 2019). Orbán’s government has employed a narrative that frames immigration as a threat to Hungary’s Christian identity and cultural homogeneity (Becker, 2019). As a result, restrictive policies have been implemented, including the construction of border barriers and the introduction of laws aimed at criminalizing support for asylum seekers.

These measures have had profound effects on social inclusion in Hungary. The narrative of an “us versus them” mentality has resulted in a climate of fear among migrants and refugees, many of whom have faced violence and discrimination (Győrffy, 2018). The historical context of Hungary’s tumultuous past has contributed to a national discourse that prioritizes ethnic homogeneity, leading to the marginalization of diverse groups. Consequently, the restrictive policies have not only limited the rights and opportunities of migrants but have also created a polarized society where fear and hostility thrive (Bugaric & Kuhelj, 2018).

In contrast, the case of Canada illustrates a different approach to populism and social inclusion. While Canada has experienced populist movements, its historical context of multiculturalism and immigration has shaped a more inclusive national identity (Triandafyllidou, 2015). Policies that promote diversity and integration, such as the Multiculturalism Act, have fostered an environment where immigrants are seen as valuable contributors to society (Kymlicka & Banting, 2006). While populist rhetoric has attempted to challenge this narrative, the overall economic and historical framework has led to a more resilient approach to social inclusion.

Canada’s commitment to welcoming refugees and immigrants has resulted in positive economic outcomes, as diverse groups bring varied skills and perspectives that enrich the workforce. However, challenges remain, particularly in addressing the needs of marginalized communities and combating discrimination (Granovetter, 1973). The contrasting experiences of Hungary and Canada underscore how historical narratives and economic conditions influence the outcomes of populist policies on social inclusion.

Another significant case study is Italy, where the rise of populism under leaders like Matteo Salvini has led to restrictive immigration policies that have profoundly affected social integration. Italy’s historical context, marked by economic challenges and high unemployment rates, has fueled a perception of migrants as competitors for scarce resources (UNHCR, 2012). Salvini’s “Italians First” campaign sought to capitalize on these anxieties, leading to policies that restrict access to social services and legal residency for migrants.

The effects of these policies have been particularly pronounced in regions where economic struggles are most acute. Migrants in Italy often face discrimination in the job market, and many are relegated to precarious employment (OECD, 2020). Additionally, populist rhetoric has fostered an environment where xenophobia is normalized, leading to increased violence against migrant communities (ECRI, 2024). This case illustrates how economic conditions, combined with populist narratives, can exacerbate the challenges faced by marginalized groups, resulting in significant barriers to social inclusion.

In summary, the consequences of populist policies on social inclusion are shaped by a complex interplay of economic and historical factors. Case studies from Hungary, Canada, and Italy reveal how these dynamics can lead to divergent outcomes in terms of social integration. Understanding these contexts is crucial for addressing the challenges posed by populism and developing strategies that promote inclusivity and social cohesion in increasingly diverse societies. By recognizing the differentiated effects of these policies, stakeholders can work towards creating environments that foster belonging and participation for all members of society.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the role of populism in redefining citizenship and social inclusion for migrants in Europe reveals a complex and often troubling landscape. The emergence of populist movements has significantly influenced citizenship laws and principles, shifting the focus toward more exclusionary practices that prioritize ethnonational identity over inclusive citizenship. Through an analysis of changes in jus soli and jus sanguinis, it is evident that populist rhetoric has led to legislative reforms that reinforce a narrow definition of national belonging, marginalizing migrant communities and reshaping the fabric of European societies.

The implications of these changes extend beyond legal frameworks to the societal level, where public perceptions of migrants are increasingly shaped by populist narratives. These narratives often stigmatize migrants, portraying them as threats to national identity and social cohesion. As a result, migrants face considerable challenges in accessing essential services, such as education, employment, and healthcare, hindering their social integration and reinforcing systemic inequalities.

Furthermore, the consequences of populist policies on social inclusion are not uniform across Europe; they vary significantly based on historical and economic contexts. Case studies from countries like Hungary, Italy, and Canada illustrate the divergent effects of populism on social inclusion, revealing how economic anxieties and historical narratives shape the experiences of migrants. While some nations adopt restrictive measures that foster division and exclusion, others maintain more inclusive approaches that recognize the contributions of migrants to society.

Ultimately, this exploration underscores the pressing need for a reevaluation of citizenship and social inclusion policies in the face of rising populism. Addressing the challenges posed by exclusionary practices and fostering a more inclusive understanding of citizenship can enhance social cohesion and resilience in diverse societies. To achieve this, it is essential for policymakers, civil society, and communities to work collaboratively in promoting narratives that celebrate diversity, combat discrimination, and advocate for equitable access to rights and opportunities for all individuals, regardless of their background. In doing so, Europe can navigate the complexities of globalization while ensuring that its commitment to fundamental human rights and social justice remains unwavering.

(*) Dr. Edouard Epiphane Yogo is a lecturer of political science and Executive Director of the Bureau of Strategic Studies (BESTRAT). He teaches at the University of Yaoundé II and has over 20 years of experience as a leading consultant in peace, security, and defense. With 11 books and more than 30 academic articles, his research focuses on security dynamics in Central Africa and the Lake Chad Basin, addressing issues like terrorism and conflict management. His expertise has contributed to numerous international peacebuilding efforts, and he regularly consults for organizations such as the United Nations System. Email: edouardyogo@yahoo.fr

References

Books

Adamidis, V. (2021). Democracy, populism, and the rule of law: A reconsideration of their interconnectedness. Res Publica, 44(3).

Gidron, N., & Bonikowski, B. (2013). Varieties of populism: Literature review and research agenda. Harvard University Press.

Giugni, M., & Grasso, M. (Eds.). (2021). Handbook of Citizenship and Migration. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Győrffy, D. (2018). Trust and crisis management in the European Union: An institutionalist account of success and failure in program countries. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kymlicka, W., & Banting, K. (2006). Immigration, multiculturalism, and the welfare state. Ethics & International Affairs, Wiley Online Library.

Mudde, C. (2019). The far right today. Polity.

Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press.

Pappas, T. S. (2019). Populism and liberal democracy: A comparative and theoretical analysis. Oxford Academic.

Talani, L. S. (2021). Populism and migration. In The International Political Economy of Migration in the Globalization Era (pp. 325–357). Springer.

Triandafyllidou, A. (Ed.). (2015). Routledge handbook of immigration and refugee studies. Routledge.

Wodak, R. (2015). The politics of fear: What right-wing populist discourses mean. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Articles

Becker, J. (2019). Review of Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism, by P. Norris & R. Inglehart. International Affairs, 95(5), 1168–1169.

Bonikowski, B., Halikiopoulou, D., Kaufmann, E., & Rooduijn, M. (2018). Populism and nationalism in a comparative perspective: A scholarly exchange. Nations and Nationalism, 25(1), 58-81.

Bugaric, B., & Kuhelj, A. (2018). Varieties of populism in Europe: Is the rule of law in danger? Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 10, 21–33.

El País. (2024). El populismo xenófobo marca el paso en Occidente.

Hawley, G. (2016). Review of White backlash: Immigration, race, and American politics, by M. Abrajano & Z. L. Hajnal. Political Science Quarterly, 131(1), 173–175.

Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (2019). Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 996-1017.

Le Monde. (2024). “Parce que notre démocratie repose sur la vitalité d’institutions républicaines solides, instaurons les garde-fous nécessaires à sa protection”.

Le Monde. (2024). Comment la gauche peut-elle combattre l’extrême droite ? Les pistes de deux philosophes pour contrer l’essor des nationalismes.

Le Monde. (2024). En Italie, la réforme de la citoyenneté au cœur des débats de la coalition de droite.

Le Monde. (2024). Présidentielle américaine 2024 : “Trump joue de cette peur ancienne de l’altérité raciale dont le suprémacisme blanc est le débouché”.

Mayer, N. (2013). From Jean-Marie to Marine Le Pen: Electoral change on the far right. Parliamentary Affairs, 66(1), 160–178.

Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 2027–2051.

Muis, J., & Immerzeel, T. (2017). Causes and consequences of the rise of populist radical right parties and movements in Europe. Current Sociology, 65(6), 933–949.

Retailleau, B. (2024). Sur l’immigration, Bruno Retailleau se pose en pourfendeur d’une société multiculturelle. Le Monde.

Soffer, D. (2022). The use of collective memory in the populist messaging of Marine Le Pen. Journal of European Studies, 52(1).

Steele, B. J., & Homolar, A. (2019). Ontological insecurities and the politics of contemporary populism. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 32(3), 1-24.

Varga, E., & Buzogany, A. (2020). Populism and anti-immigrant sentiment in Central and Eastern Europe: The case of Hungary and Poland. East European Politics, 36(2), 161-178.

Varga, M., & Buzogany, A. (2020). The foreign policy of populists in power: Contesting liberalism in Poland and Hungary. Geopolitics, 26(1), 1-22.

Wojczewski, T. (2019). ‘Enemies of the people’: Populism and the politics of (in)security. European Journal of International Security, 5(1), 1-24.

Reports and Institutional Publications

European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI). (2024). Annual report on ECRI’s activities, covering the period from 1 January to 31 December 2023. Council of Europe.

Manatschal, A., Wisthaler, V., & Zuber, C. I. (2020). Making regional citizens? The political drivers and effects of subnational immigrant integration policies in Europe and North America. Regional Studies, 54(11), 1475-1485.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2015). Sociocultural dimensions of immigrant integration. In The integration of immigrants into American society. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). International migration outlook 2020.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2012). Hungary as a country of asylum: Observations on the situation of asylum-seekers and refugees in Hungary. UNHCR.

Theses and Other Publications

Dahlgren, P. (2006). The Internet, public spheres, and political communication: Dispersion and deliberation. Political Communication, 22(2), 147–162.

Destradi, S., & Plagemann, J. (2019). Populism and international relations: (Un)predictability, personalization, and the reinforcement of existing trends in world politics. Review of International Studies, 45(5), 1–20.

Inglehart, R. F. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-026.

Jones, E. (2019). Testing liberal democracy: Populism in Europe: What scholarship tells us. Survival, 61(4), 7–30.

Löfflmann, G. (2022). Introduction to special issue: The study of populism in international relations. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 24(3).

Methods and Tools

Loyer, B. (2019). Géopolitique : Méthodes et concepts. Armand Colin.

Rannikmäe, M.; Holbrook, J. & Soobard, R. (2021). Social constructivism: A new paradigm in teaching and learning environment. In Science education in theory and practice (pp. 259–275). Perennial journal of history, 2(2).

Thual, F. (1996). Méthodes de la géopolitique : Apprendre à déchiffrer l’actualité. Relations internationales et stratégiques.

Zajec, O. (2018). Introduction à l’analyse géopolitique : Histoire, outils, méthodes. Éditions du Rocher.

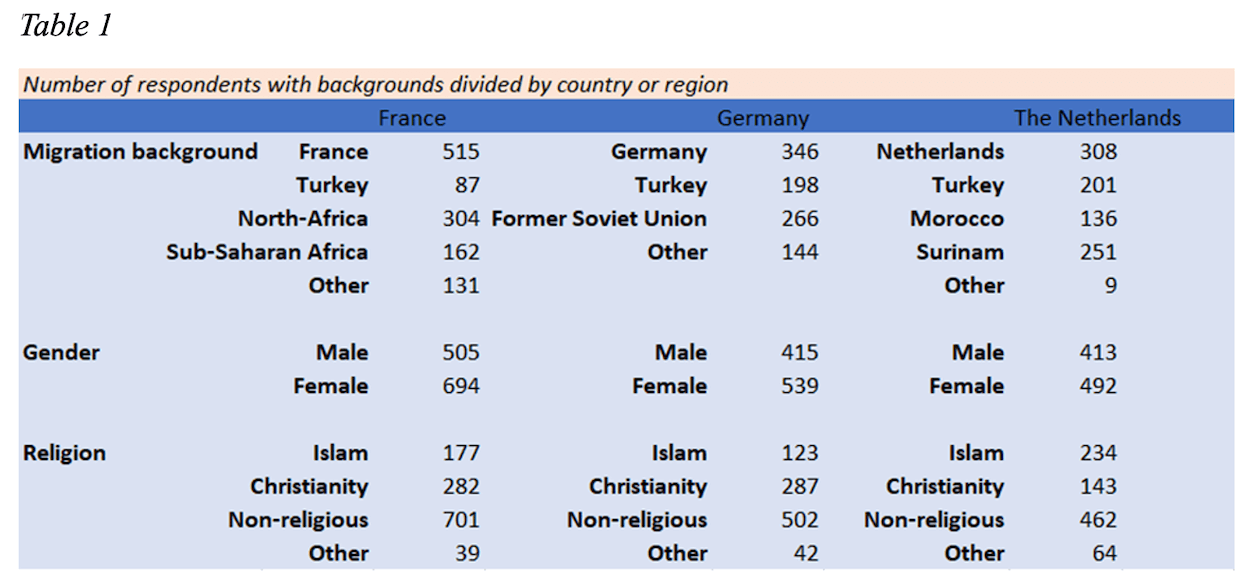

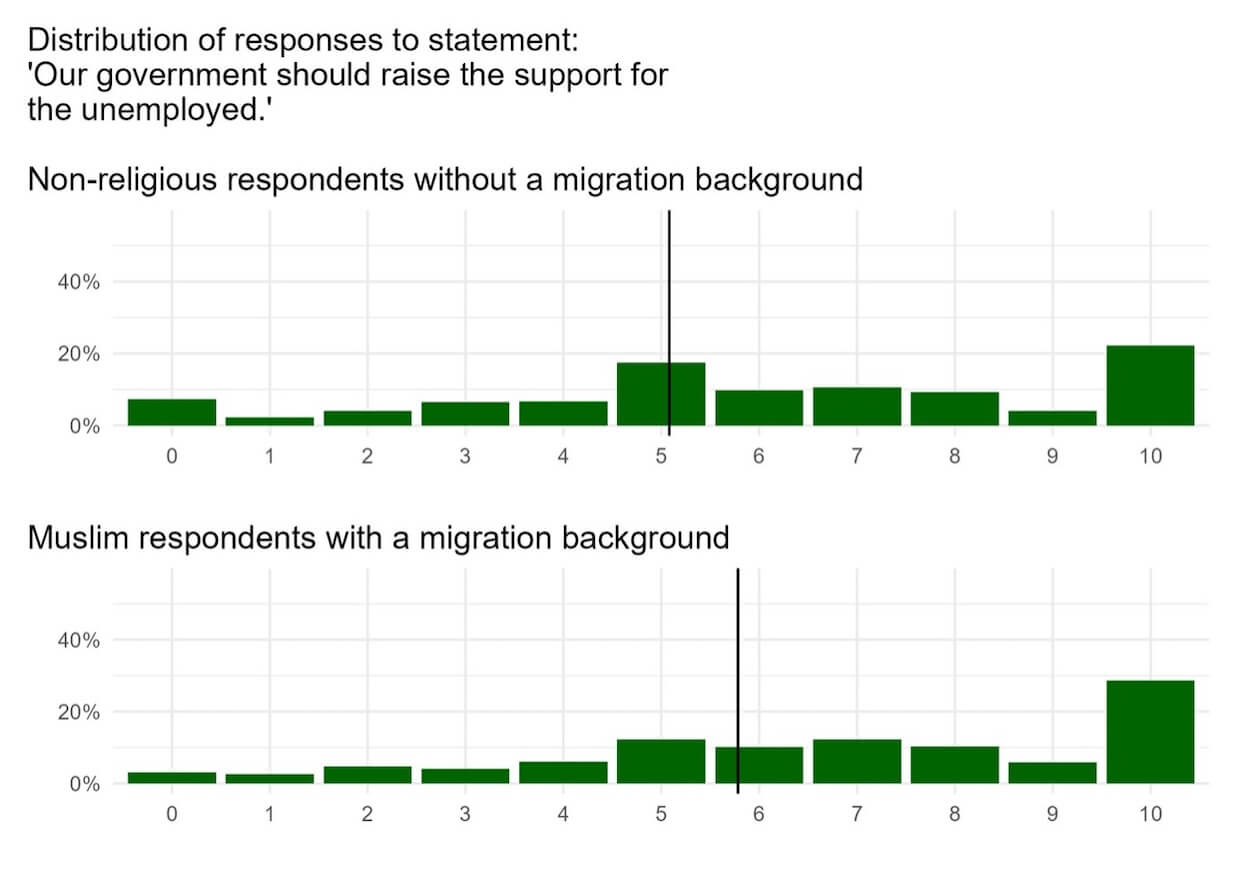

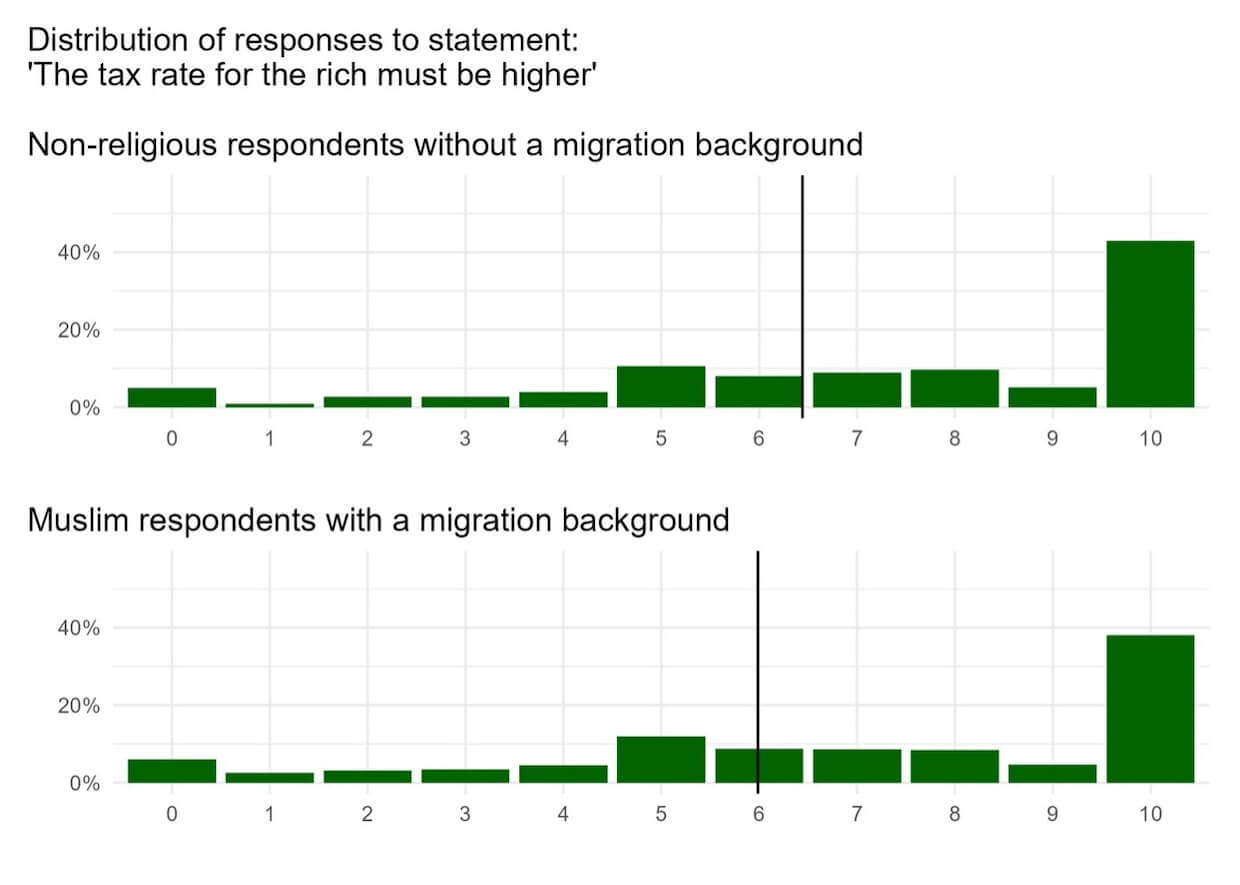

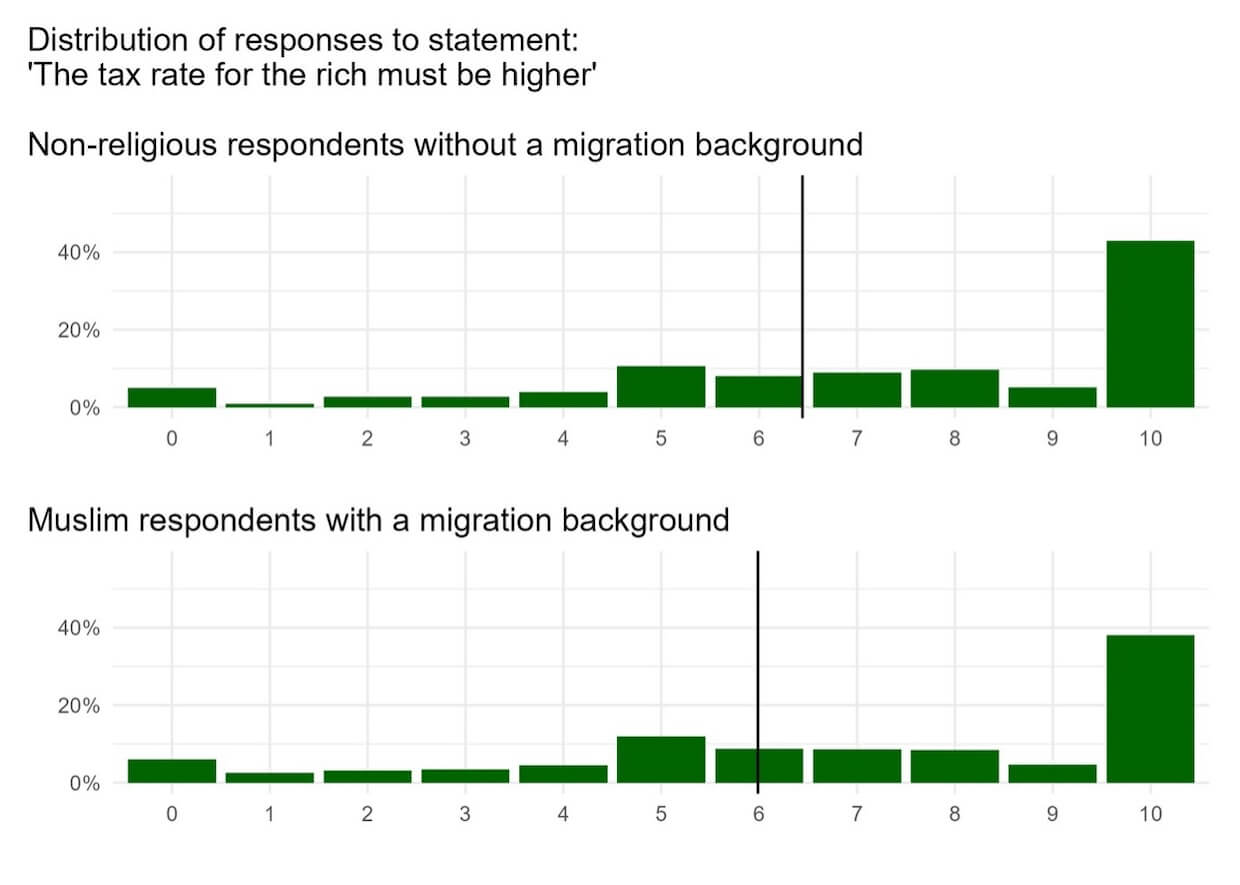

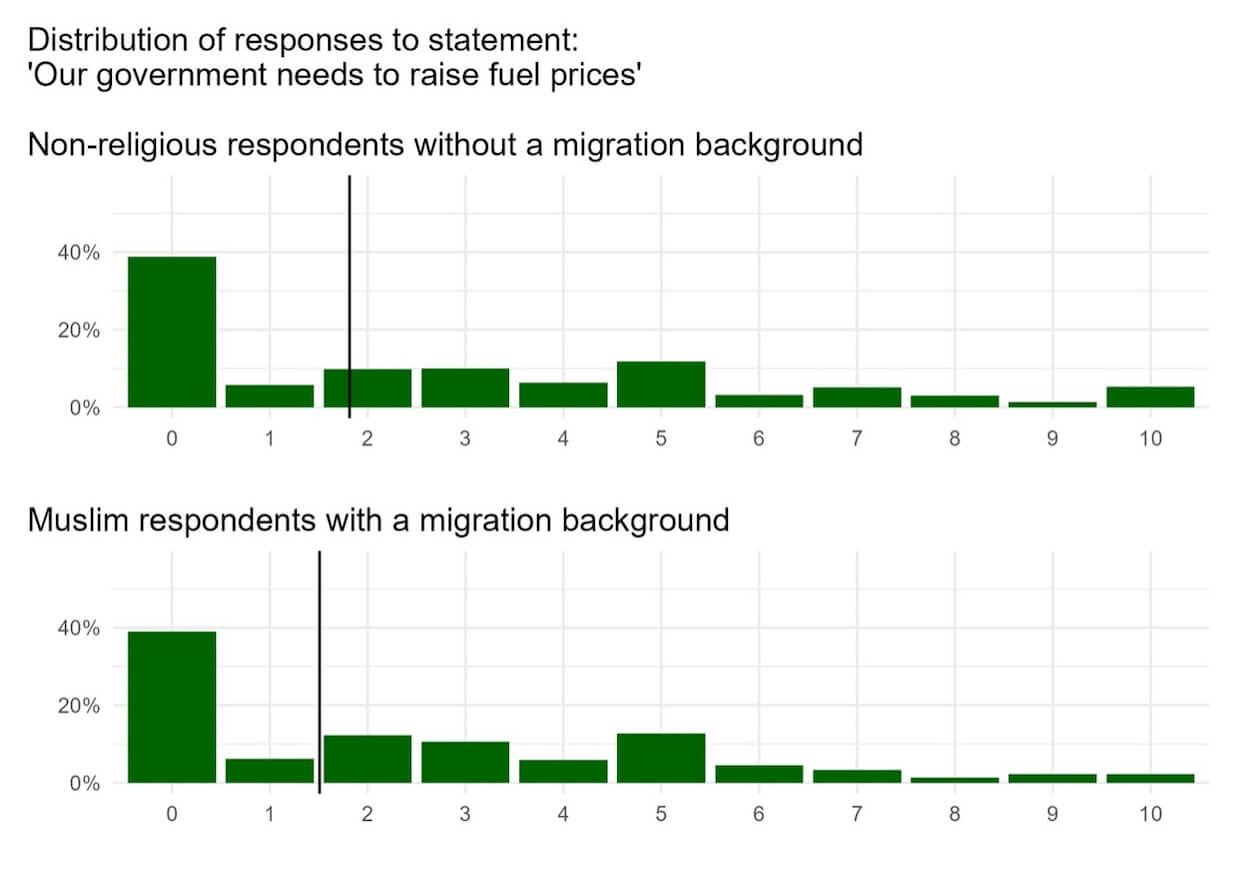

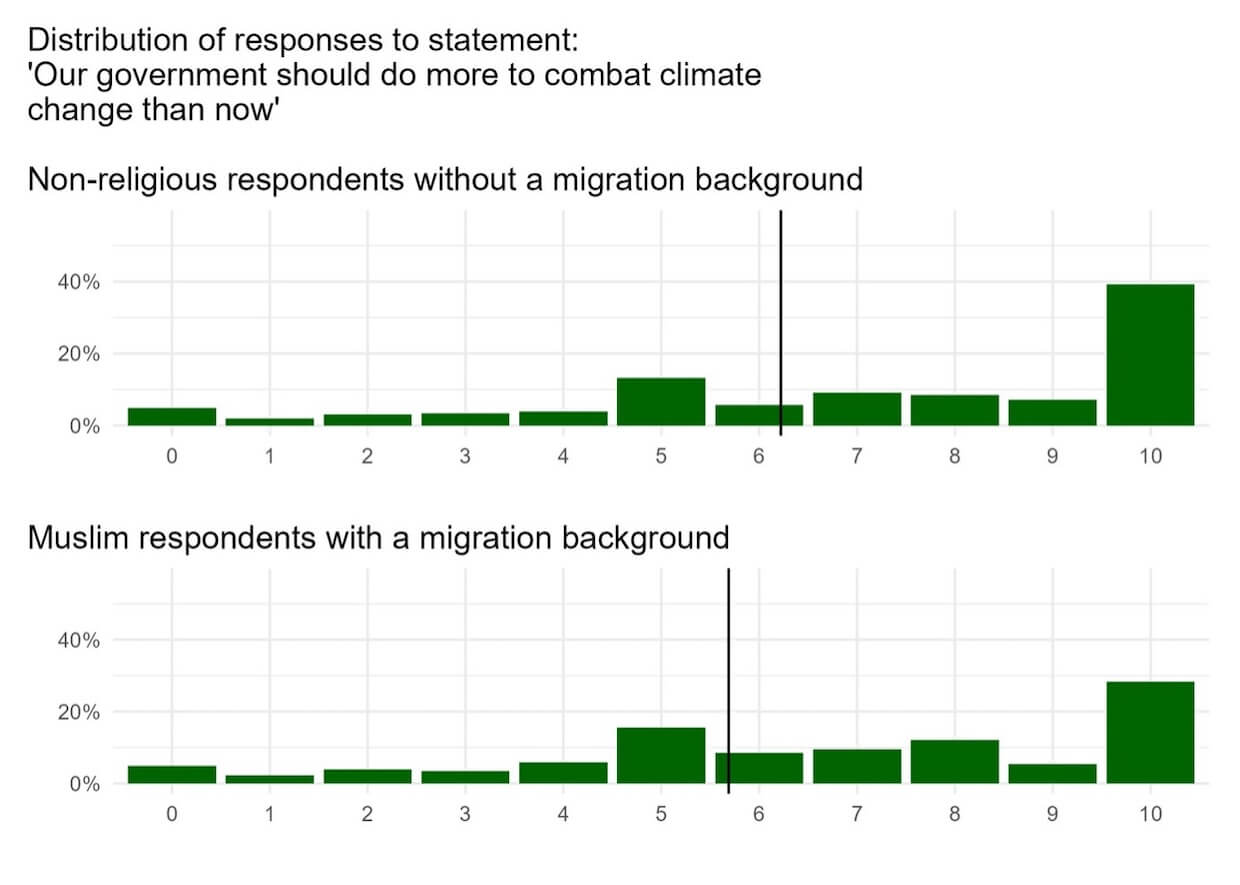

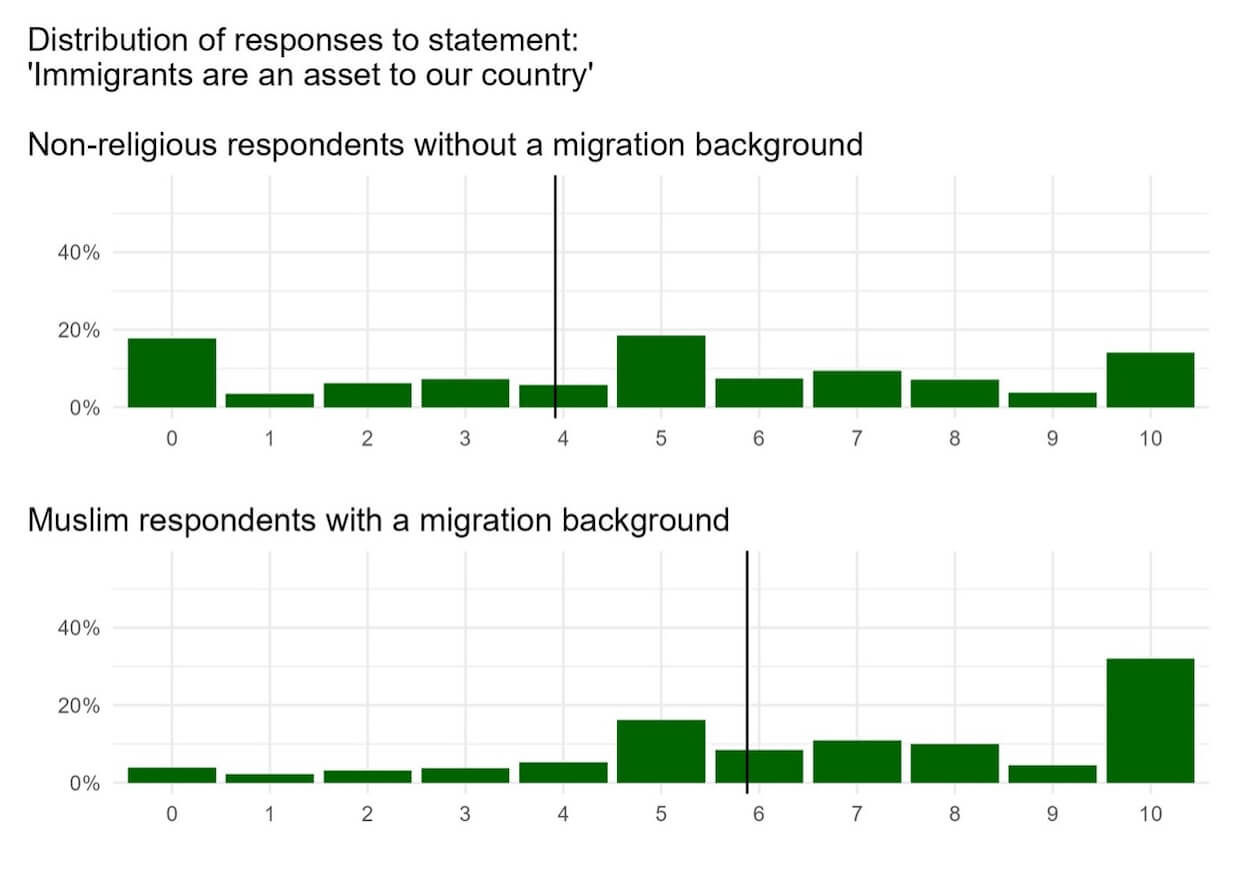

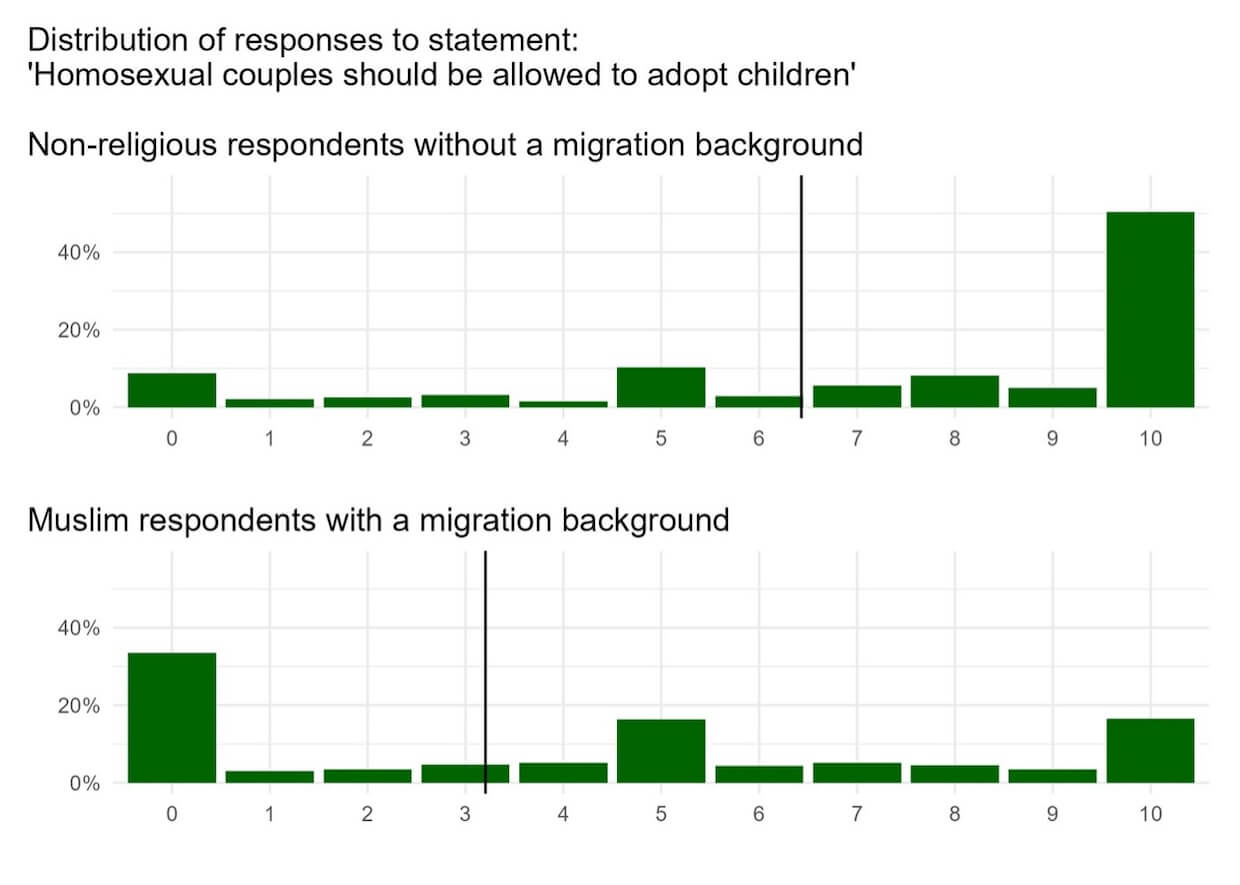

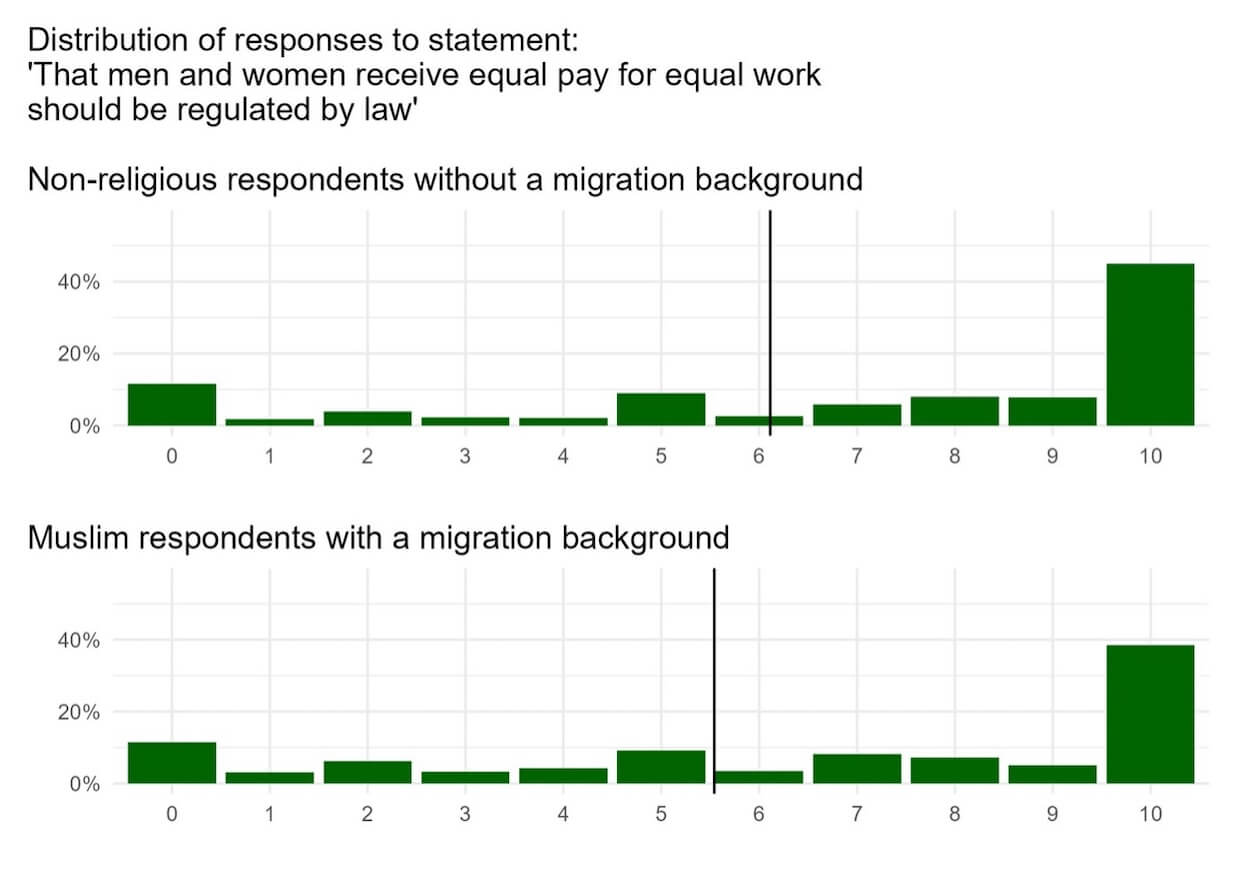

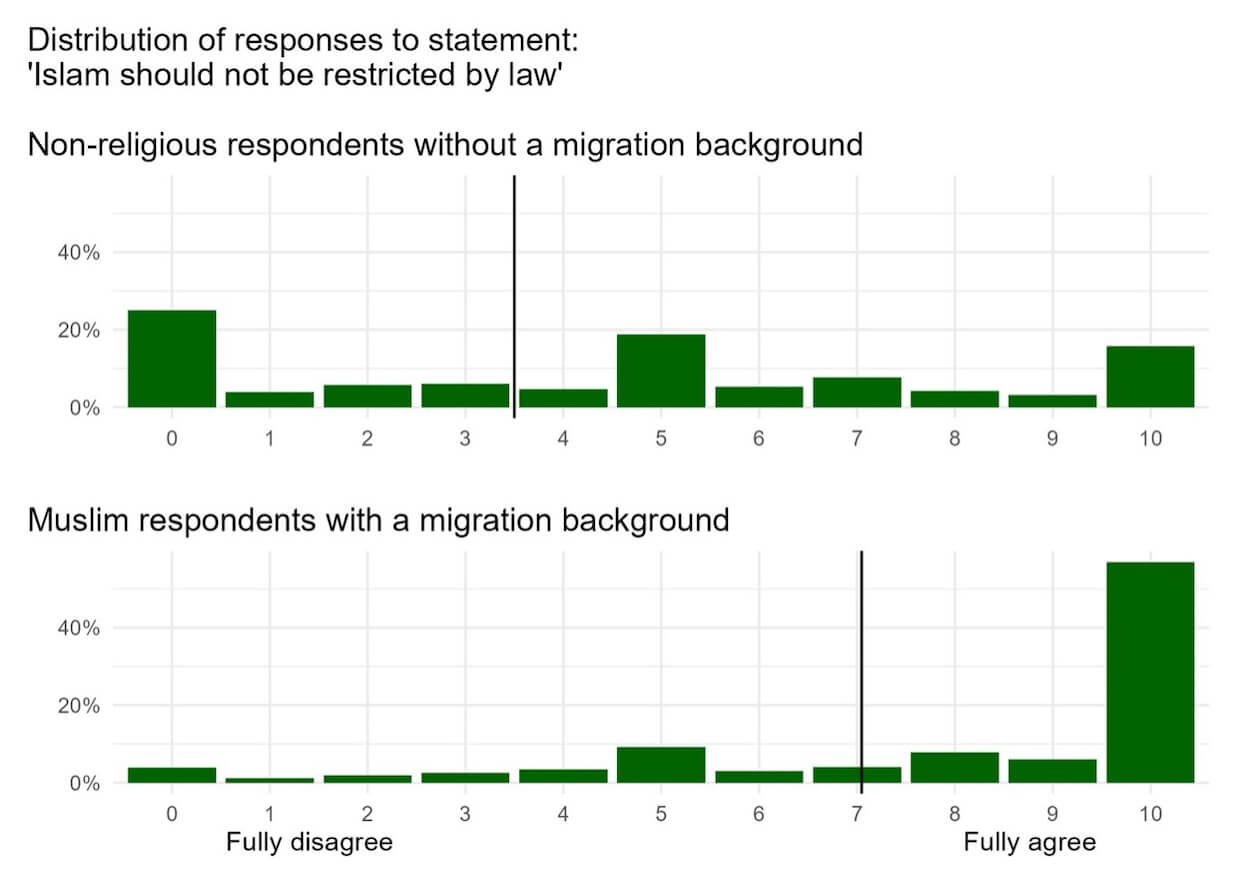

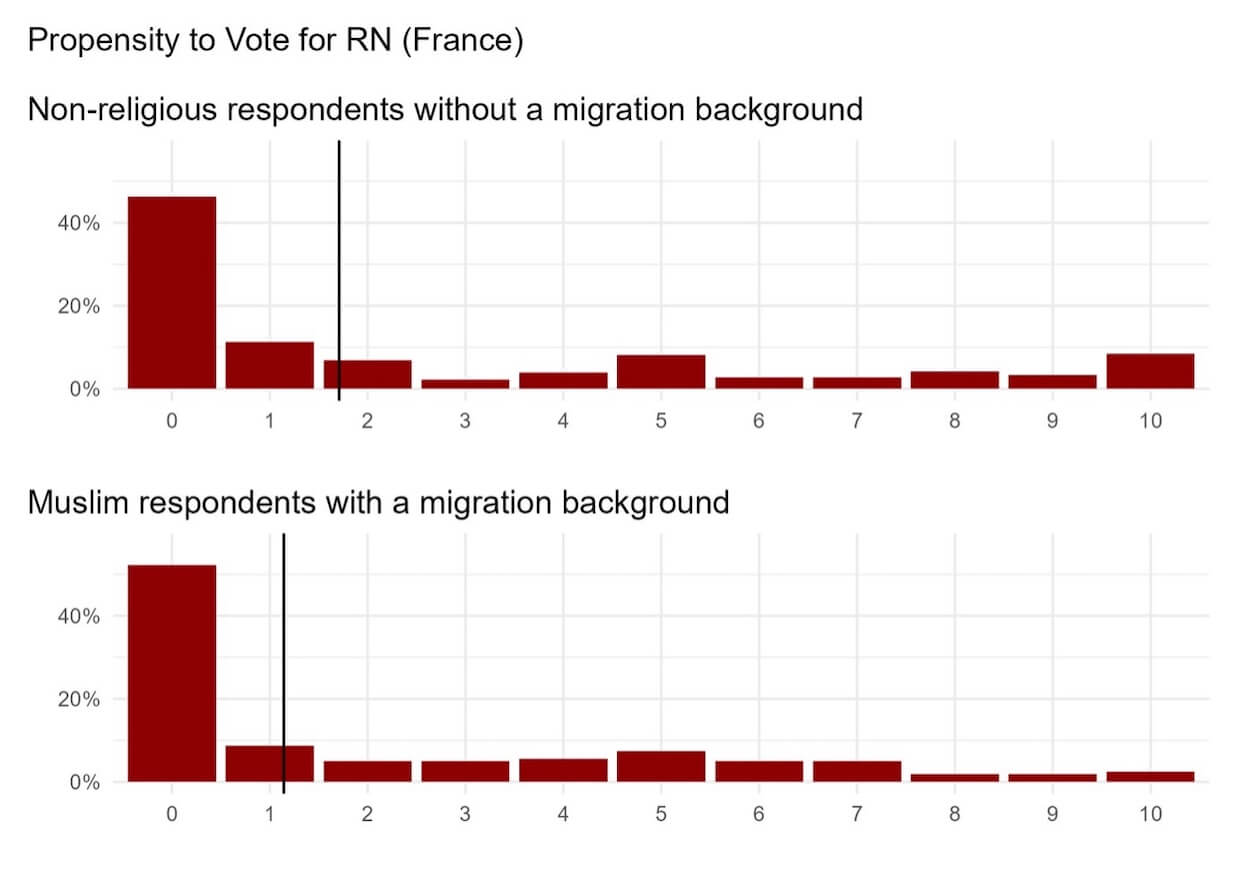

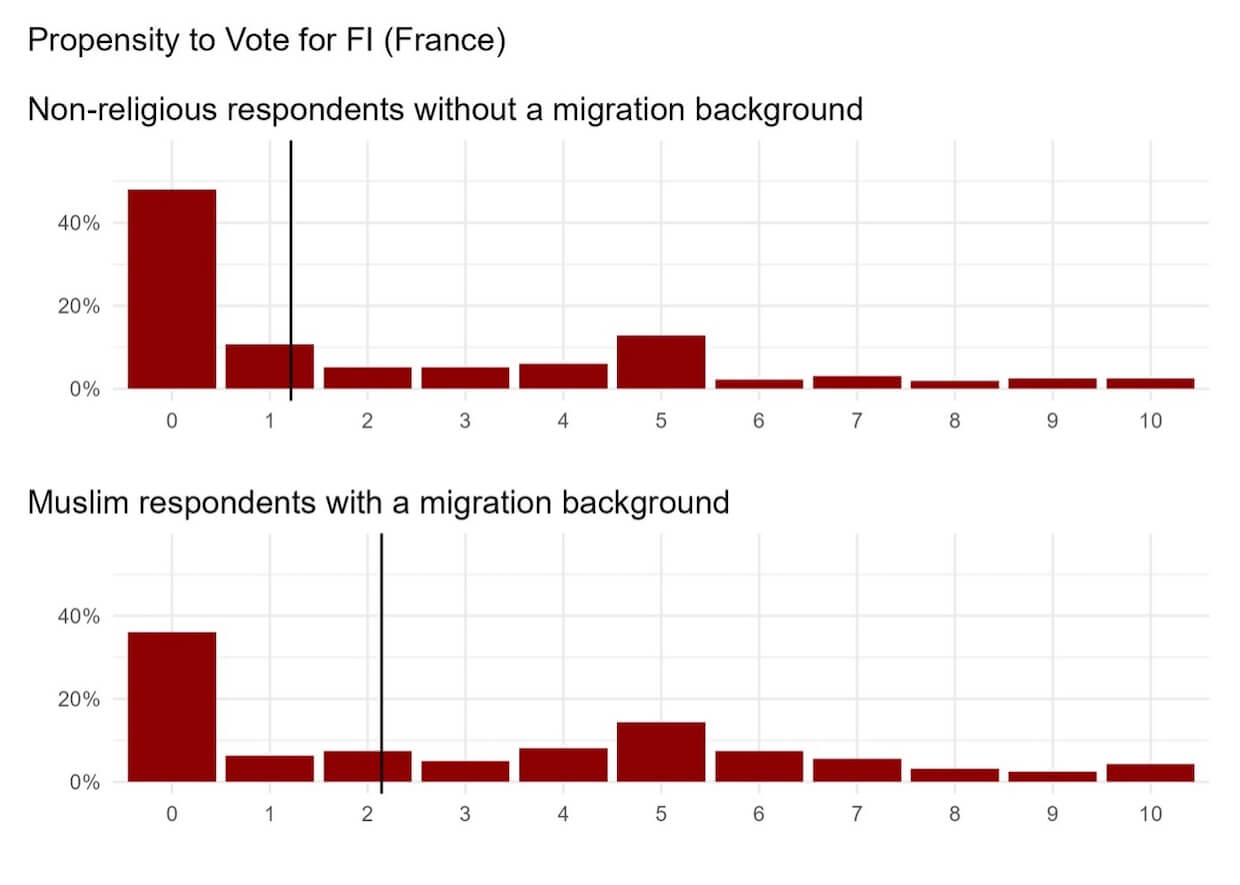

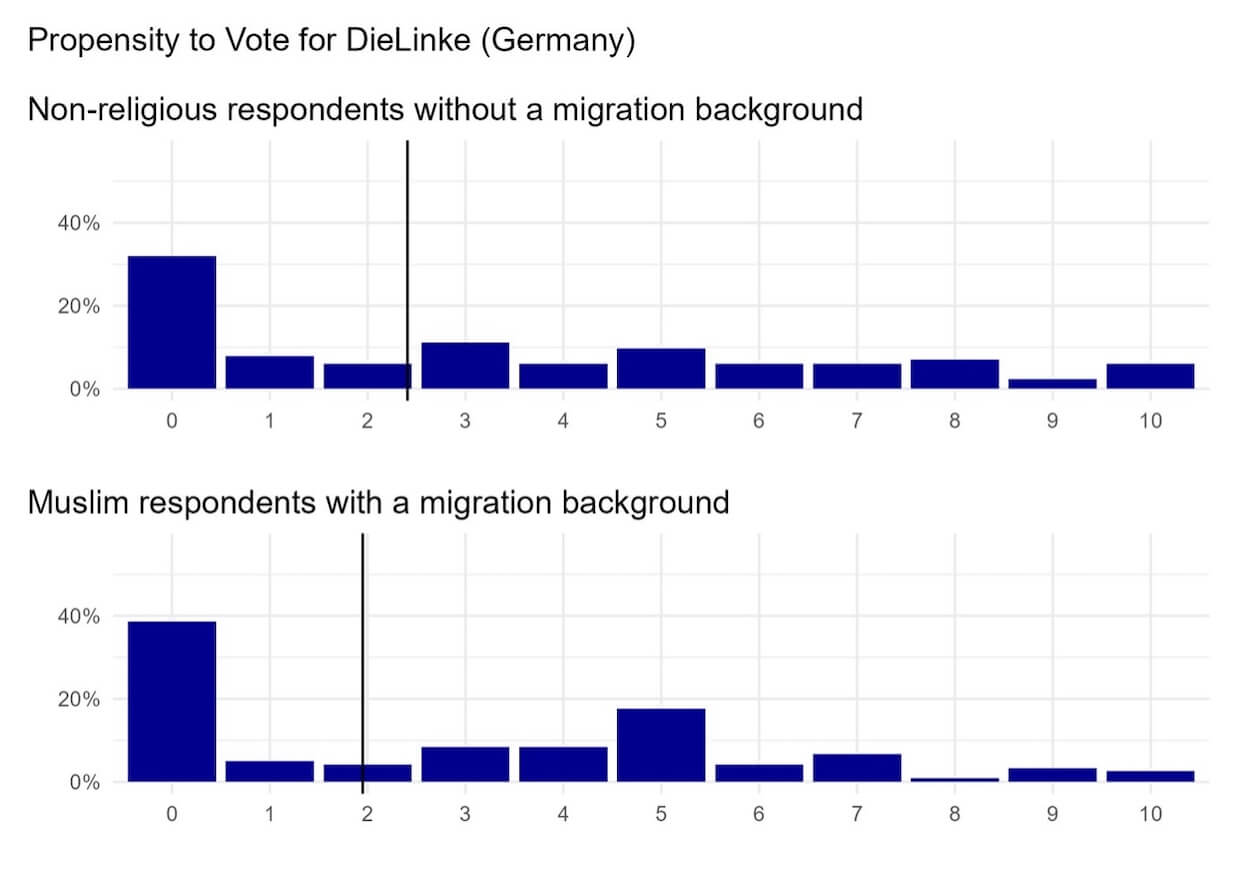

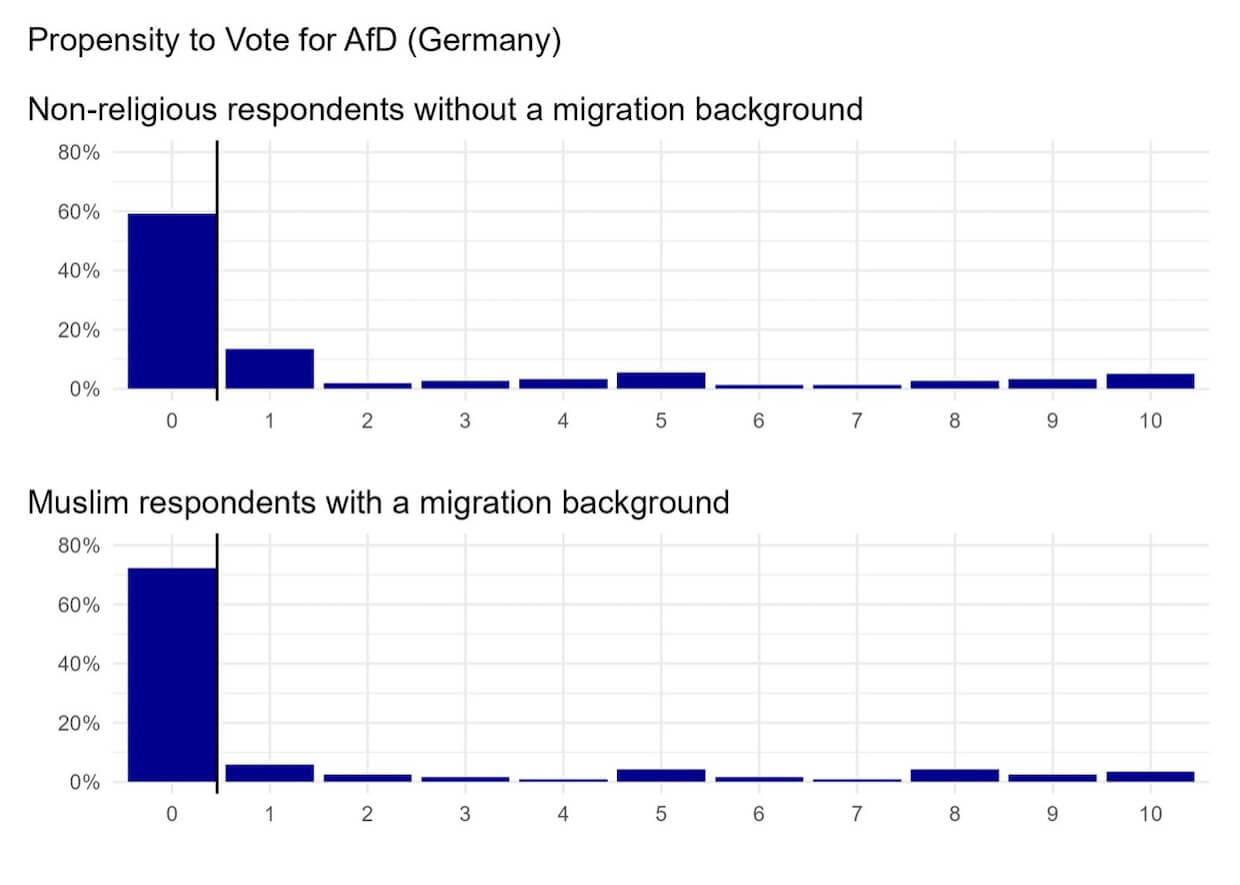

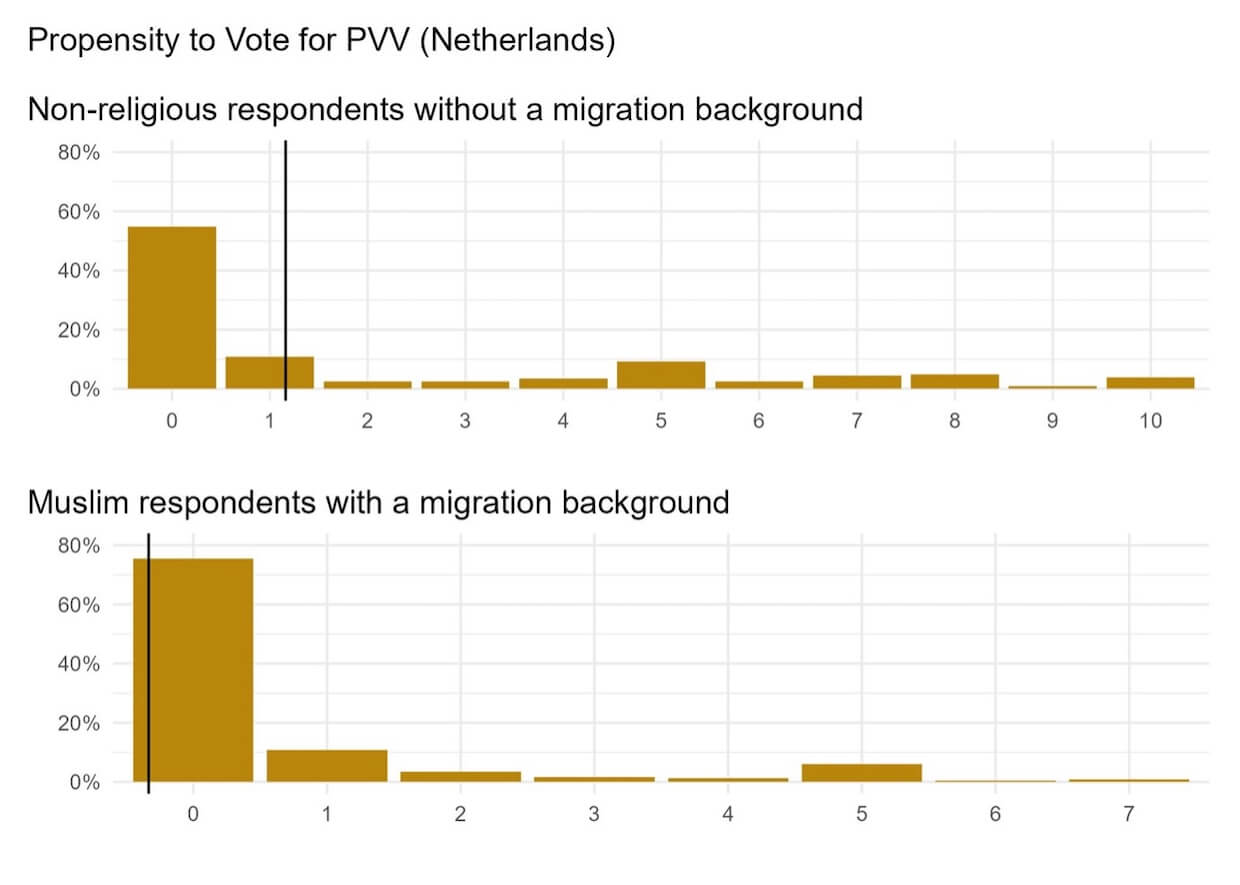

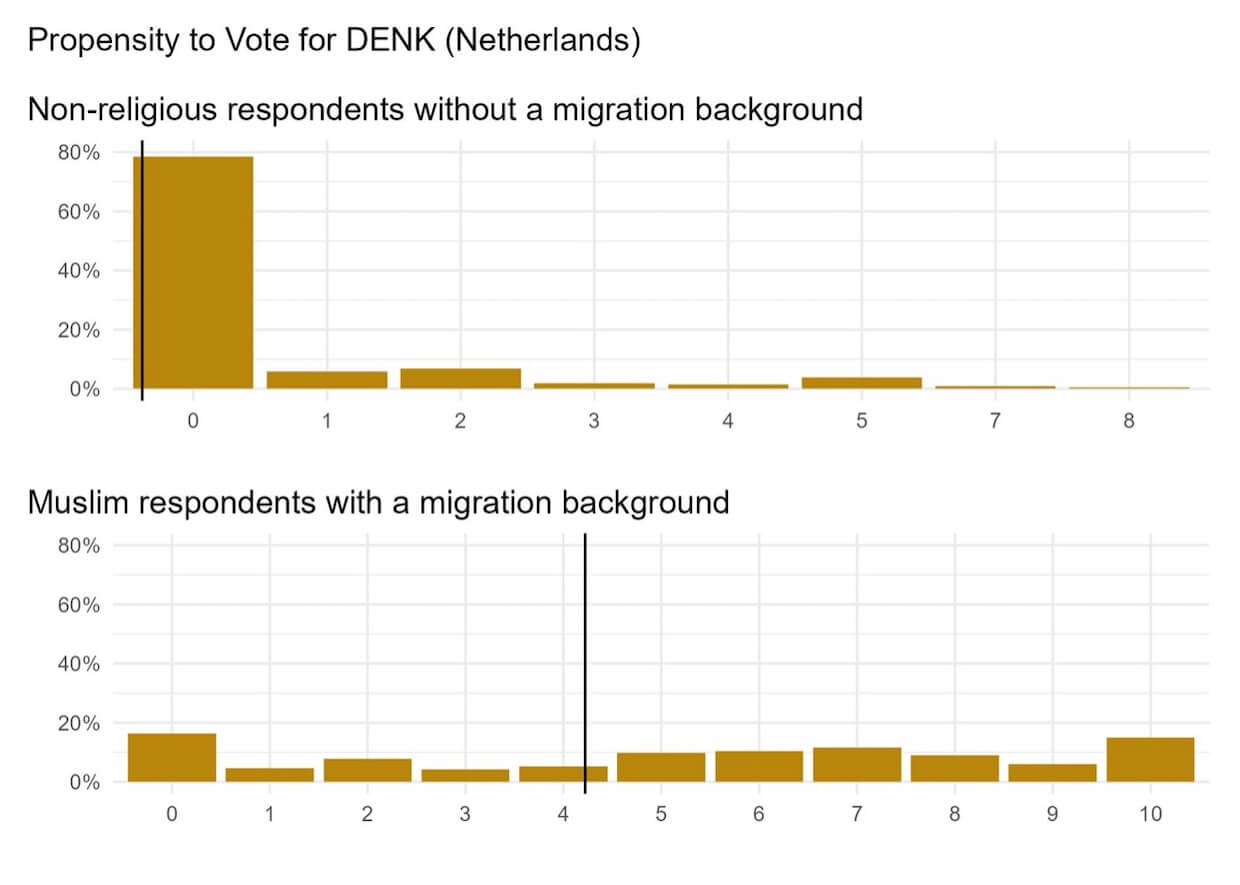

I assessed migration background by inquiring about the birthplaces of respondents’ mothers and fathers. It was necessary to ask this question first for sampling purposes. To minimise potential ordering effects on the data, I randomised the order in which respondents viewed the policy questions and experimental profiles (for the full questionnaire, see appendix in van Oosten, 2025c). To mitigate acquiescence bias, where respondents tend to agree with statements, I randomised the wording of the policy questions. For instance, one half of the sample saw the statement: “the taxes for this rich should be raised” and the other half saw “the taxes for the rich should be lowered” and I recoded the variables accordingly. I prepared the data using R-package ‘tidyr’ (Wickham, 2020, see all code and replication materials here: van Oosten, 2025c).

I assessed migration background by inquiring about the birthplaces of respondents’ mothers and fathers. It was necessary to ask this question first for sampling purposes. To minimise potential ordering effects on the data, I randomised the order in which respondents viewed the policy questions and experimental profiles (for the full questionnaire, see appendix in van Oosten, 2025c). To mitigate acquiescence bias, where respondents tend to agree with statements, I randomised the wording of the policy questions. For instance, one half of the sample saw the statement: “the taxes for this rich should be raised” and the other half saw “the taxes for the rich should be lowered” and I recoded the variables accordingly. I prepared the data using R-package ‘tidyr’ (Wickham, 2020, see all code and replication materials here: van Oosten, 2025c).

Conclusion

Conclusion