In an interview with the ECPS, Professor Thiemo Fetzer argues that populist grievances are largely shaped by perception rather than lived experience. “Populism is a phenomenon of information overload,” Fetzer explains. “Many grievances amplified by populists are not grounded in demographic or economic realities but are shaped by narratives, particularly those spread through modern media.” Discussing global trade, economic inequality, and the rise of far-right movements, he warns that misinformation fuels discontent, making societies more vulnerable to populist rhetoric. From the future of the liberal order to the geopolitics of energy, Fetzer offers a data-driven perspective on the forces reshaping today’s world.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In an interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Thiemo Fetzer, an economist at the University of Warwick and the University of Bonn, argues that populist grievances are largely rooted in perception rather than actual lived experiences. However, as he warns, populists are particularly adept at exploiting these narratives for political gain.

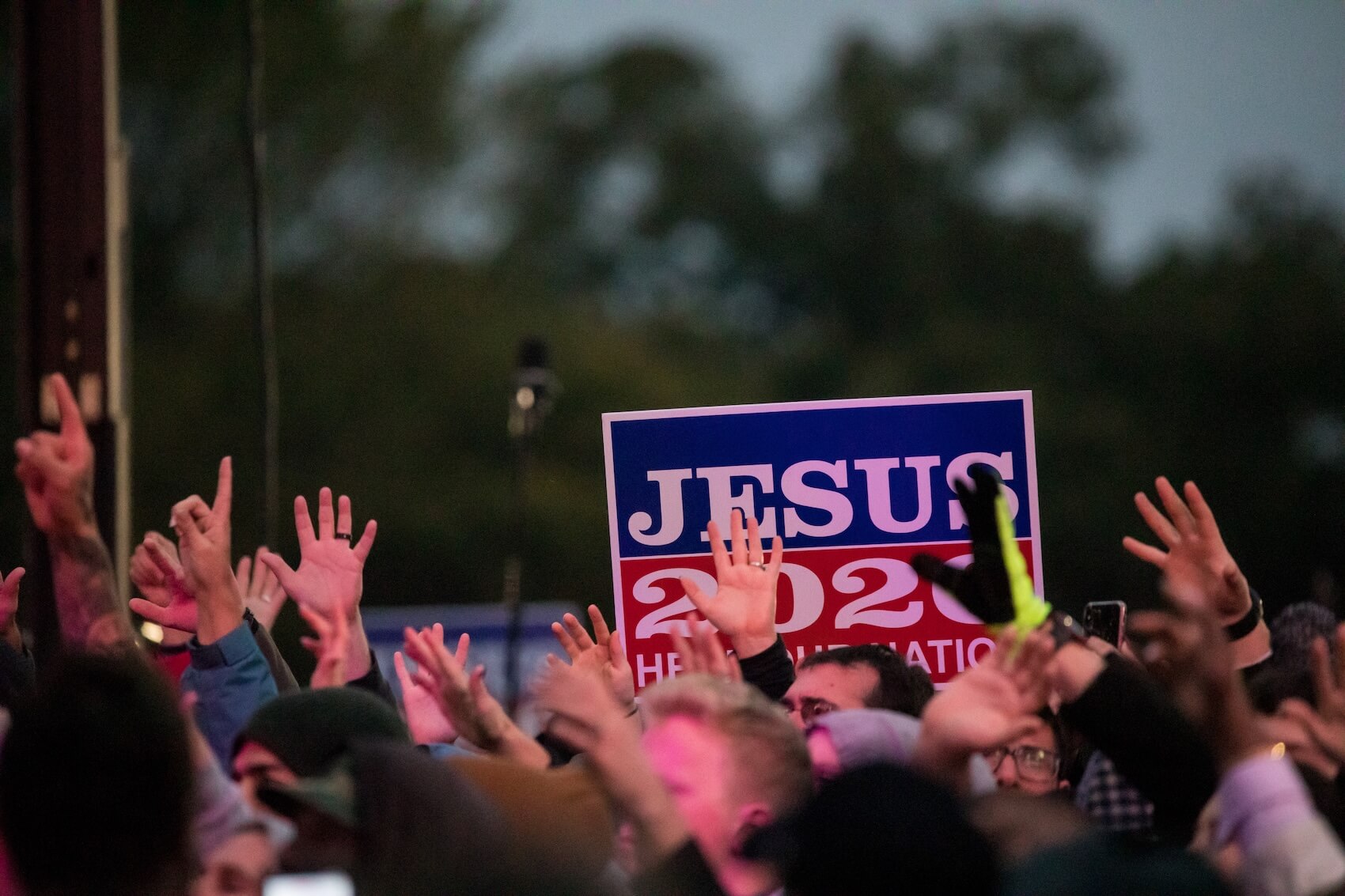

“Populism is a phenomenon of information overload,” Professor Fetzer explains. “Many grievances that populists amplify are not based on actual demographic or economic realities but are shaped by narratives, particularly those spread through modern media.” He highlights how, in many cases, communities most resistant to immigration often have little to no firsthand experience with immigrants—a paradox that underscores the role of perception over reality.

Professor Fetzer’s research delves into the economic, political, and social forces driving contemporary populism. In this interview, he explores the dynamics of global trade, industrial policy, economic inequality, and geopolitical shifts, particularly in the wake of a second Trump presidency.

Discussing global trade realignments, he explains that while China has aggressively localized production and built dominance over key supply chains, the US has primarily specialized in financialization, service-sector trade, and digital technology. This has led to geopolitical tensions, as China’s strategic control over minerals and industrial supply chains threatens US economic leadership.

Regarding the rise of far-right movements like the AfD in Germany, Professor Fetzer stresses that economic grievances alone do not fully explain their appeal. Instead, he argues, populist movements often thrive on a combination of perceived cultural shifts, economic anxieties, and declining trust in institutions.

He also critiques the role of digital media in fueling discontent, stating that “the collapse of traditional media landscapes has created an environment where misinformation and sensationalized narratives shape public perception more than facts.”

Finally, addressing the decline of the liberal world order, he challenges the idea that neo-mercantilism and protectionism signal its end. Instead, he suggests that a shift toward industrial policy—particularly in the energy sector—has long been in motion.

With economic nationalism, trade wars, and geopolitical realignments defining today’s global landscape, Professor Fetzer provides a data-driven perspective on the forces shaping modern populism.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Thiemo Fetzer with some edits.

Global Trade and the US-China Rivalry

Thank you very much, Professor Fetzer, for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: How would a second Trump presidency reshape global trade dynamics? Given his previous and current tariff policies and confrontational trade stance, which sectors and economies are most vulnerable to renewed trade wars?

Professor Thiemo Fetzer: That is an incredibly complex and intriguing question. One important aspect to consider is the evolution of the international division of labor over the past 10–15 years, which provides context for the US trade policy maneuvers. Of course, this is my interpretation of the data and evidence, and I acknowledge that it may not be entirely accurate.

Over the last 20, or even 30 years, a global division of labor has emerged. The US has largely specialized in financialization, focusing on service sector trade, particularly through its digital tech companies, as well as its expertise in knowledge production and innovation. Meanwhile, China has aggressively localized production and strategically established dominance over key supply chains, particularly in industries that are crucial for global priorities such as climate action.

China is undoubtedly a leading player in decarbonization technologies, including renewable energy, photovoltaics, wind power, and electric vehicles. While the US has specialized in service sector trade, China has strategically developed control over value chains in industries that are not only considered the future of global economies but also essential for addressing climate challenges.

This context is key to understanding the confrontational dynamics and geopolitical rivalry between the US and China. While Europe is also engaged in this contest, it has not deindustrialized to the same extent as the US and has pursued a different specialization path.

A crucial element of this geopolitical contest is control over strategic minerals and supply chains. China holds significant leverage due to its dominance in mineral processing and access to raw materials. In response, the US is now aggressively shifting toward industrial policy, making efforts to secure access to critical minerals and supply chains through a mix of policy initiatives and strategic trade measures.

This is happening alongside increasing disputes over trade governance. Countries that specialize in service sector trade—particularly in knowledge production and innovation—rely heavily on intellectual property protections. However, a key point of contention between the US and China is that not all countries adhere to the same intellectual property governance standards. This discrepancy plays a major role in the US’s more aggressive stance in trade policy.

From a strategic perspective, the US has been outmaneuvered in certain areas by other geopolitical players—one of the most prominent examples being critical minerals. Both the US and Europe have been making efforts to develop alternative supply chains for rare earth elements and other crucial materials needed for technologies such as semiconductors and renewable energy infrastructure.

However, China has weaponized its control over these resources, particularly through its dominance in mineral processing and reserves. One interpretation is that China has deliberately disrupted competitors’ efforts to establish alternative supply chains by strategically releasing mineral reserves to drive down prices, thereby making it economically unviable for private enterprises in market-based economies to compete.

This dynamic mirrors what we observed in the early 2010s, when US shale oil and gas production disrupted global energy markets. Historically, energy-exporting countries—such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE—played a dominant role in setting crude oil prices through export relationships with the US. However, the rise of US shale production significantly weakened their influence by creating a new source of swing production capability.

There is a clear parallel here, highlighting the broader clash between economic and social systems. The primary challenge for the US and Western players is the short-term policymaking horizon within democratic systems, where leaders operate within fixed electoral cycles. In contrast, non-democratic regimes—as we define them within representative democracy frameworks—can pursue long-term strategic planning without the same political constraints.

These tensions are now coming to the forefront, and the US is responding aggressively, using trade policy as a key instrument to counterbalance these structural disadvantages.

The Rise of Protectionism and Economic Realignment

What are the long-term risks of Trump’s trade policies for global economic stability? With the US not only decoupling from China but also distancing itself from the EU and shifting alliances, how might geopolitical fragmentation and economic realignment unfold?

Professor Thiemo Fetzer: Again, there are ways of trying to think about the future path. And I mean, on average, I would like to think that the US’s specialization in service sector trade, which is actually something that the UK, in particular the Brexiteers, strongly advocated, has made both the UK and the US quite vulnerable.

Service sector trade, particularly in the digital economy, digital goods, and so on, has a relatively high degree of localization potential. At the end of the day, many of the digital services we consume are controlled by global tech platforms like Google, Microsoft, and others. However, we have seen, for example, in Latin America, where language was a barrier, strong and competitive local players emerging and capturing parts of these value chains, preventing them from falling entirely under the control of major US brands. A key example is Mercado Libre in Latin America. Similarly, in China, a big tech ecosystem developed independently because the market never fully opened to major US tech players.

This has been a longstanding political tension, particularly between the EU and the US, well before the first Trump administration. Big tech companies generate enormous revenues from highly scalable products, where a single innovation can reach an infinitely large market. However, global governance frameworks around service sector trade have struggled to adapt to this reality, as tax and regulatory systems were originally designed with goods trade in mind.

This has created a wedge issue in Europe, where big tech firms access large markets but transfer profits to offshore tax havens, leading to disputes over digital taxation. Under Trump’s first presidency, both the UK and France attempted to impose digital service taxes, which challenged the US advantage in service sector trade. Currently, the US exports services, knowledge, and innovation while protecting them through intellectual property agreements and benefiting from transfer pricing mechanisms. Meanwhile, the US also absorbs excess global production, leading to imbalances in both goods and services trade.

Trump challenged this structure in 2016, particularly through aggressive tax cuts. As European countries sought to impose digital service taxes, the US responded with tax incentives that enabled American tech firms to repatriate profits from offshore havens. This disrupted the traditional global division of labor, where Europe and China produced goods while the US dominated services. While US tech firms never gained the same market access in China that they had in Europe, these shifts threatened the existing equilibrium.

With a second Trump presidency, I expect a continuation of Trump-era policies, with service sector trade pitted against goods trade. On average, the US economy could become more balanced by leaning into industrial policy and shifting slightly away from services, which has become somewhat excessive. However, the US may struggle to accept that this rebalancing could also prompt other countries to localize their own tech sectors, leading to the regionalization of digital trade.

We have already seen this trend in Latin America and China, where local tech champions have emerged. This could further encourage tech companies with more geographic focus or even explicit localization mandates, potentially driven by differing regulatory frameworks on private data governance. The regulatory landscape itself could create further friction in global trade.

In addition, the tense security situation in Europe, with Russia’s aggressive actions, could accelerate these trends, particularly if the US is no longer seen as a reliable partner but rather as a potential adversary in certain domains.

Three years ago, I warned that a second Trump presidency could end the NATO alliance, a scenario that would pose serious challenges for Europe given its dependence on the US for security. This shift could also disrupt the international division of labor, as Europe has historically granted US big tech firms market access while simultaneously struggling with taxation issues related to these firms’ profits being transferred offshore.

If this equilibrium is disrupted, I expect significant policy shifts in Europe. However, Europe may struggle with its own contradictions, as it lacks a unified tech ecosystem that could compete with US or Chinese tech giants. Unlike the US, where service sector trade is deeply integrated across states, Europe remains a collection of nations with high trade barriers in services.

This contradiction has been highlighted by figures like Enrico Letta and Mario Draghi, as well as in Brexiteer arguments, which claimed that service sector trade is the future and that Europe struggles with integration in this area. This situation is inherently risky, but at some level, perhaps necessary, if global trade is no longer governed by common standards.

Since 2016, we have seen a clear deterioration in global trade governance, accompanied by escalating trade conflicts. The situation today is highly dangerous and challenging.

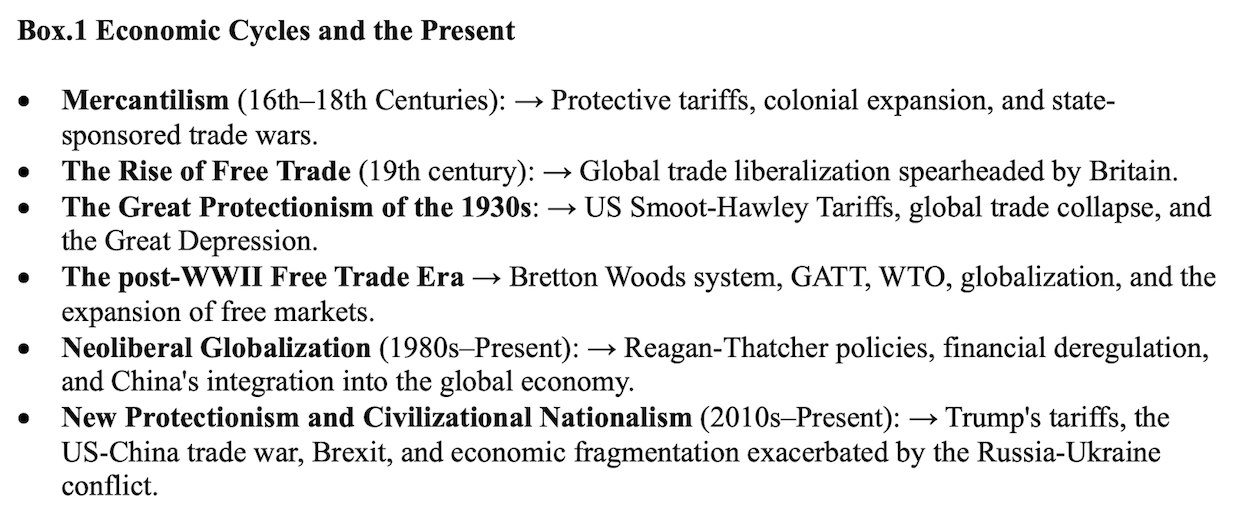

All of this unfolds amid climate crises, rapid population movements, the weaponization of illicit migration, and demographic challenges. We are navigating an exceptionally fraught and difficult global landscape.

Populism, Economic Discontent, and the Role of Media

Your research highlights economic discontent as a driver of populism. How might Trump’s policies—such as protectionism or tax reforms—exacerbate or mitigate this trend globally?

Professor Thiemo Fetzer: When we look at discontent, oftentimes it can be attributed not necessarily to people being materially worse off. I mean, if we zoom out, we are actually in a situation where the world has never been richer than before. People are well-off, and we no longer experience the type of abject poverty that existed in the past. Even in Europe, despite the rise of populism, we have seen a gradual but consistent rise in living standards.

The big challenge with populism is that it is very successful in channeling narratives around discontent. This connects to my past research on austerity in the UK, where we saw the withdrawal of the state from many public functions. There was a wave of technological optimism, similar to what we see now with AI, suggesting that automation could make public services more efficient and reduce the financial burden on the economy.

However, all of this happened amid structural changes in consumption patterns due to the rise of the Internet, which accelerated economic transformation. Many people perceived these changes as a decline in their lived environment and a disruption of the status quo.

Across people’s life cycles, older individuals tend to feel more insecure with rapid change. In the UK, for instance, two key pro-populist voting blocs—particularly strong supporters of Brexit—were older people and those expressing dissatisfaction with the status quo. Populism often unites an unlikely coalition of voters, including those who oppose any type of change.

For example, when the high street declines visibly, when shops disappear, or when routine habits are disrupted, older individuals may struggle to adapt to these changes. We lack strong lifelong learning institutions to help older people adjust to a rapidly evolving world. In this context, simplistic populist messages that blame outsiders—such as immigrants, foreign competitors, or geopolitical rivals like China—become an easy and appealing narrative.

However, we know from hard data that in the communities where populism thrives, there are often no significant immigrant populations. This highlights a disconnect between actual demographic data and perceptions, showing that populist narratives shape public opinion more than lived experiences.

A major missing link in this discussion is the role of the media. I studied this in the context of what I call the media multiplier—a phenomenon that has intensified with the rise of social media and the decline of traditional media. Many older populations, who may not be digitally literate, struggle to differentiate between reliable information and disinformation.

This changing media landscape has been weaponized by geopolitical adversaries to influence public sentiment. As a result, populist grievances are more rooted in perception than in actual lived experiences, yet populists excel at exploiting these narratives.

Looking back at austerity, we can see its role in hollowing out state functions. In the UK, for instance, we saw cuts to youth programs, a visible decline in police presence, and reductions in public services. While these changes may have been made rationally, their perceived impact was significant.

Even if crime rates did not rise dramatically, people felt less safe because they were told they were less safe. Isolated violent incidents—such as terror attacks—further reinforce perceptions of chaos and loss of control, which populists exploit to advocate for border closures and nationalistic policies.

If this trend escalates, we are not far from restricting the flow of information, similar to what we see with China’s Great Firewall. This would directly contradict the foundational principles of Western liberal democracy.

It is crucial to recognize that accelerated structural change has visible and tangible consequences, particularly in societies unaccustomed to rapid transformation. In many developing countries, social and economic shifts happen much faster than in Europe.

Our political and governance institutions, however, have not adapted to this new pace of change. While some nations have moved from extreme poverty to relative wealth in a single generation, Western institutions have struggled to keep up with global transformations. This creates a major point of friction that populists exploit.

We have people who resist any type of change because it happens so quickly that they struggle to process it. At the same time, our political systems—particularly democratic ones—face the constant challenge of power struggles and the difficulty of explaining complex relationships to the average person. As a result, these complexities are often oversimplified into digestible narratives. This is precisely where populists excel—by reducing intricate issues into simplistic, emotionally charged messages. This, I believe, is one of the major challenges we face today. In many ways, populism is a phenomenon driven by information overload—a reaction to the overwhelming complexity of the modern world.

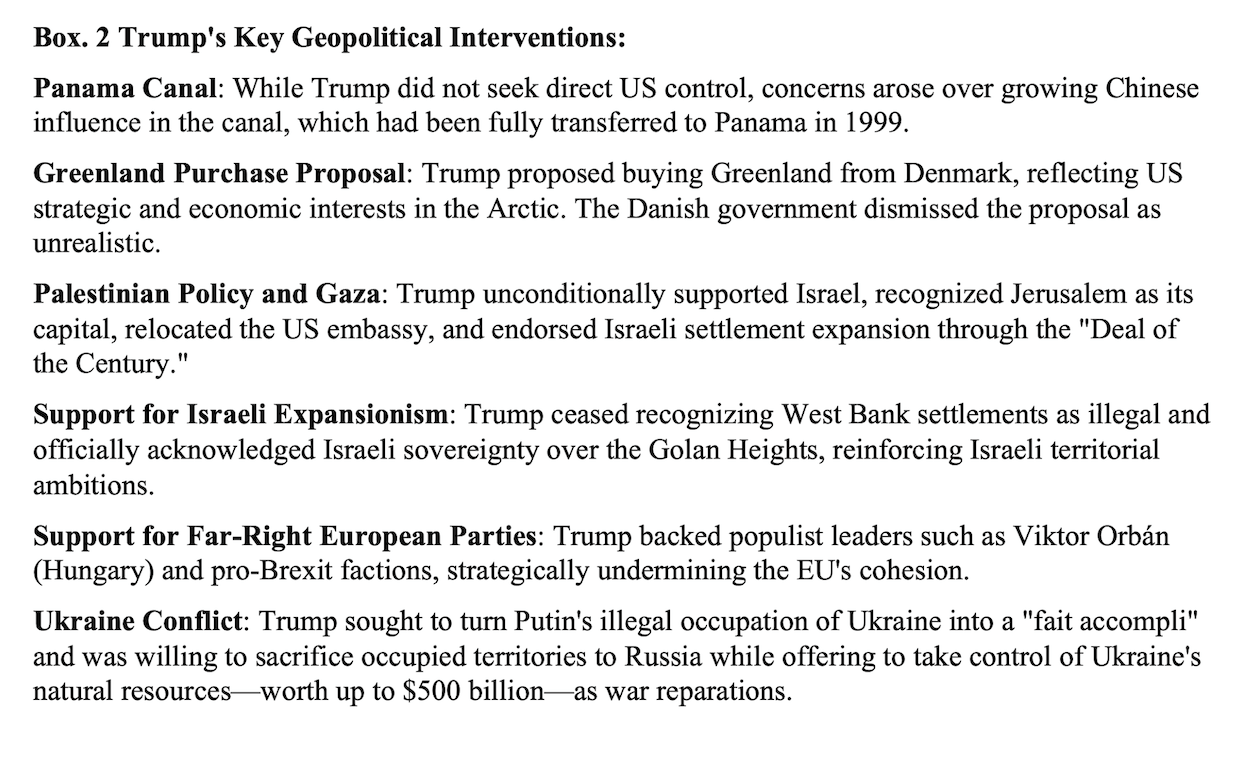

The AfD’s Success and the Geopolitical Fragmentation of Europe

How much role did economic grievances play in the strong showing of AfD in German elections last Sunday?

Professor Thiemo Fetzer: The country has been in recession for the last two or three years. However, if we consider the scale of the economic challenge and the shock caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the country has actually performed quite well in the grand scheme of things. It has cushioned these shocks reasonably well, though in a manner that might be irritating to global partners. This is why I suggest that Putin has weaponized a potential hypocrisy—because with the invasion, Europe, while championing global climate action and striving to build coalitions for sustainability, simultaneously expanded energy subsidies for hydrocarbons to help households and businesses absorb the shock.

Setting that aside, both the country and the continent have managed remarkably well in handling this multi-dimensional crisis. From a comparative advantage perspective, there has been a loss of access to cheap energy, which poses a major challenge for the industrial sector. On the other hand, the security shock and the broader disruption of the international security order have further complicated the situation.

To me, it was entirely predictable that a second Trump presidency could begin to question the foundational pillars of Europe’s security and the international division of labor. That’s why I highlighted this more than three years ago. However, in light of and despite that shock, Europe has, on average, managed quite well. That said, the AfD has been highly effective in channeling this narrative, questioning why Europe should position itself as a global leader in climate action and why the EU should advocate for a rules-based free trade system governed by law rather than force. In the broader context, Europe has performed well, and individual member states have managed to navigate these challenges effectively.

The major contradiction and risk at this moment is that individual European countries are being systematically picked apart, one by one, by geopolitical adversaries. It even appears that, in some ways, the US may be playing a role in this dynamic.

However, given the broader context, I remain cautiously optimistic, as this is truly a make-or-break moment for Germany within Europe and for Europe as a whole. To me, it has never made sense—though these numbers are hypothetical, they are probably not far from reality—for Portugal to maintain an independent air force with just four F-35s and a handful of tanks, when in reality, landing troops on the coast would already be a major challenge.

Now, there is a unique opportunity arising from the geopolitical pressure Europe is facing, both from the war in Ukraine and the uncertainty surrounding its security partnerships. This pressure could serve as a catalyst for Europe to build a common, integrated defense capability, something that has been attempted in the past but never fully realized. In this sense, we could be witnessing the emergence of a stronger European statehood.

Since this is happening within a highly challenging security landscape, it will inevitably drive shifts in industrial policy, sovereignty debates, and strategic planning. Europe must not only develop its defense capabilities with international partners beyond the EU, but also focus on building efficient and sustainable supply chains within Europe itself to ensure long-term resilience.

I am beginning to see emerging partnerships in this context, particularly in the Middle East, which holds strategic significance for Europe. The recent Suez Canal blockade, even though accidental, underscored the region’s critical role. Additionally, Turkey could become a key partner in this evolving dynamic. I also believe this shift could potentially bring the UK closer to Europe again, as it has a vested interest in participating in the expanding European defense cooperation. However, the US appears to be actively trying to pull the UK away from deeper European integration in this regard.

This, to me, defines the broader geopolitical context in which the AfD has been able to thrive. The party has successfully tapped into simplistic narratives that resonate with public sentiment, yet the solutions it proposes are entirely incompatible with the actual challenges that Europe faces. And for that, it’s really important.

Again, populist parties tend to make a country seem bigger than it is. The UK experienced this with populism, attempting to reinvigorate the idea of the old empire. However, when the UK then tries to reestablish ties with its former empire—whether with India or Pakistan—these are now emerging powers and significant players in the global division of labor. The Indians respond, “Well, UK, okay, that’s interesting, but you’re a tiny, tiny country in the grand scheme of things.” This reality applies to each individual EU member state. That is why it is crucial for the broader public to reflect on this: if Germany wants to chart a path that is optimal and beneficial for itself within Europe and the world, it is entirely dependent on working in conjunction and in very close partnership with others.

But again, this is a make-or-break moment, a make-or-break situation. Geopolitical adversaries—whether China, Russia, the UK, or even the US—all have an interest in a divided Europe, and to some extent, we are already seeing this play out. This is where Europe must step up and build a form of sovereignty. To me, this begins with establishing a European fiscal capacity, which is a necessary condition to ensure that many of the founding pillars of the European Union, originally intended to drive European integration, are no longer exploited as tools by adversaries. Key areas that require urgent reform include privacy regulation, the incompleteness of tax frameworks, the lack of integration in national tax systems, and information sharing—all of which must be addressed.

I do think that figures like Enrico Letta and the Draghi report have made it clear that the solutions are obvious. The real question now is whether a pan-European movement or a pan-European critical mass can be built to actually implement these solutions. However, this remains extremely challenging and difficult because economic interest groups within each individual nation-state benefit from maintaining exclusive contracting relationships within their own national jurisdictions. This has been the biggest obstacle to service sector integration and, ultimately, could become the very mechanism of its own downfall. If this continues, it could lead to countries becoming increasingly inward-looking, which in turn could result in the unraveling of the European project itself.

Cultural Backlash vs. Economic Factors in Populism

Many scholars argue that cultural backlash, rather than economic factors, drives populism. How does your research challenge or complement this perspective?

Professor Thiemo Fetzer: Culture is a tricky thing. If we look at the data, the immigration topic is a salient and important one to consider here. Societies in Europe—the whole idea of European freedom of movement—is built on creating an integrated European labor market, fostering the emergence of a European identity and a European culture. This is particularly relevant for smaller countries because, geopolitically and globally, they are relatively insignificant in terms of projecting force or influence. It is much more difficult for them to do so, which makes this context particularly important.

To me, the cultural dimension is a very vague concept—it often serves as a catch-all excuse when the underlying economic or societal mechanisms cannot be precisely identified. Earlier, I alluded to this challenge in the context of immigration. The biggest backlash to immigration comes from communities that have no actual experience with immigration. This highlights how perceptions of different social groups—such as immigrants—are often entirely detached from real lived experience. That, to me, is the big challenge. If one wants to call that culture, so be it.

But consider the food system. One of the biggest successes in terms of food is what is commonly known as the Turkish kebab. My sister lives in a small town in the Swabian Alps in southern Germany, and one of the most successful businesses in her town is the local kebab shop. However, the type of kebab you find in Germany does not actually exist in Turkey. It is a product of cultural integration, a fusion that emerged through the blending of different influences.

This illustrates why perceptions, lived experiences, and the extent to which they are grounded in hard evidence are the most critical battlegrounds of all. I believe that media systems, which facilitate the spread of narratives and stories about “the other” or the unknown, play a crucial role here. This is where we, as societies, must take responsibility for investing in the absorptive capacity of our communities—engaging with different cultures, reaching out, and ensuring that the shaping of stereotypes is not left solely in the hands of those who control media reach and influence.

This is one of the major dividing lines emerging between the US under Trump and Europe, particularly in discussions about how to regulate social media and make it function more effectively. Of course, this is a highly complex and controversial topic.

To put it simply, what we often call culture is largely built on stereotypes, rather than lived experience. The vast majority of individuals who advocate for re-migration or the separation of communities do so based on narratives rather than firsthand interactions. This is a key battleground, but it requires investment in a society’s absorptive capacity and clear mandates for those who migrate—to share and participate in the evolving way of life. Culture is not static; it evolves over time and requires investment from both the receiving and the sending sides.

Germany, in particular, has made significant historical mistakes in this context. Turkish guest workers were regarded merely as temporary guests, with the expectation that they would eventually return home. Similarly, in the early 1990s, many Bosnian refugees arrived, yet little effort was made to facilitate their integration. The same applied to ethnic Germans from the former Soviet Union—despite having been entirely socialized in Russia or the Soviet Union, they were presumed to require no language or cultural integration, solely because they possessed German lineage or passports. This was a fundamental fallacy. In more recent years, Germany has invested significantly in improving integration and absorptive capacity, but this primarily benefits medium and large cities, while rural areas remain largely untouched by these efforts.

The same mechanisms that apply to immigration also apply to economic migration trends—entrepreneurial, risk-taking individuals are typically the ones who migrate, while those who prefer stability and familiarity tend to remain in their communities. For individuals in rural areas with limited direct exposure to migrants, the lack of firsthand contact can reinforce perceptions shaped entirely by media narratives rather than real-life experiences.

This is the generational challenge facing every European country. That is why, to me, the term culture is not particularly helpful in these discussions. It often serves as a placeholder for a lack of understanding, when, in reality, there are concrete ways to foster economic integration and investment in assimilation.

Big cities provide excellent examples of how successful integration can work. The real challenge is how to extend these benefits to smaller communities. One potential solution is remote work, which allows individuals to experience the advantages of cultural and economic agglomeration—typically found in diverse urban environments—without the need for physical relocation.

Ultimately, this could help shape a shared future. After all, what we consider German culture today did not exist 200 years ago. Germany was a collection of hundreds of small states and communities, yet over time, a German identity emerged. The same process is now unfolding at the European level, and some even argue that this mechanism should extend to a global level, fostering shared prosperity and understanding in an increasingly interconnected world.

And lastly, Professor Fetzer, the liberal world order, founded on interdependence after the collapse of communism, was once seen as the inevitable future, with Francis Fukuyama declaring the “end of history” and the triumph of liberalism. With the resurgence of neo-mercantilist and protectionist policies, can we now say that history is reasserting itself and that the liberal order has become a relic of the past?

Professor Thiemo Fetzer: What’s implicit in this question is a consideration of the role of the state. Mercantilism, in one interpretation, is based on the idea that the state has a mandate to shape economic development in one way or another. In contrast, the extreme form of liberalism—libertarianism—argues that the state should not exist at all, with everything being guided solely by market forces.

A lot of the tensions we see today, at least from my perspective, revolve around charting a more sustainable future for the planet. We are now realizing that our way of life, particularly in the Global North, imposes negative externalities on communities elsewhere—through global warming, environmental degradation, and the resulting instability. Climate change is already inducing population movements, particularly in Africa, where nomadic communities are struggling to find water for their herds. As they are forced into cities, this disrupts existing societal equilibria, often leading to conflict and instability. Unfortunately, these changes are happening very fast, making adaptation even more difficult.

If we accept this premise, then we must reconfigure how our economies function. This requires a role for the state or supranational institutions to shape incentives and engineer a systemic transition toward a more sustainable equilibrium. Achieving this demands the deployment of a broad economic policy toolkit, often referred to as industrial policy.

Energy Transitions and the Battle Over Industrial Policy

Germany actually pioneered aspects of this transition in the early 2000s, introducing high subsidies for solar and wind energy production. Crucially, these subsidies were designed in a non-discriminatory way, making them compatible with global rules-based trade under WTO regulations. As a result, German subsidies played a key role in creating today’s renewable energy giants in China.

At some level, I find it difficult to view this as a negative development, because it offers a realistic pathway for systemic transition. It presents the possibility of maintaining, or even improving, high living standards, while socializing the benefits of natural resources—such as renewable energy. In the long run, the cost of energy could converge toward the cost of capital, since solar panels and wind farms require minimal ongoing expenses once installed. The world has vast amounts of barren land that could be used for energy production, allowing us to harvest the abundance of the planet. But achieving this required a shift in policy, which, unsurprisingly, faced resistance from economic interest groups.

Traditionally, many would blame oil-rich countries in the Middle East—such as Saudi Arabia or the UAE—for opposing energy transitions. However, in reality, some of the strongest resistance came from hydrocarbon producers with much higher production costs, particularly in the US and other regions.

In the Middle East, the cost of producing a barrel of crude oil is around $10, allowing these countries to continue profiting massively even as global energy markets shift. However, in the US shale industry, production is far more expensive and comes with major externalities, such as methane leakage, which are not properly priced into the system.

For these higher-cost producers, the energy transition poses a major financial threat. The biggest opponents of the transition—originally driven by forward-looking industrial policies in Europe (particularly Germany) and later seized upon by China—were actually mid-tier hydrocarbon producers in Africa, Latin America, and especially the US, where high capital costs create risks of stranded assets.

In contrast, producers in the Middle East are likely to be the last oil suppliers standing, as their low production costs allow them to outcompete higher-cost producers. To me, this transition in the energy system was strategically initiated through industrial policy. However, it was repeatedly disrupted, largely by hydrocarbon interests from mid-cost producers—most notably, those in the US.

This is not an unreasonable conclusion, given the structural nature of the US energy sector. In most countries, oil extraction is a public revenue source or controlled by a state monopoly. However, in the US, landowners hold subsurface mineral rights, a unique legal framework that allows private individuals to profit from oil production. As a result, many small landholders have deeply invested in non-renewable energy and have a strong financial interest in maintaining the status quo. This explains why hydrocarbon interests wield such strong political influence in the US. Meanwhile, oil-rich nations in the Middle East are likely content to let American hydrocarbon interests do the lobbying for them, ensuring continued hydrocarbon production and market stability.

The Future of the Liberal World Order

Stepping back to the broader question—is this the end of history? If we compare liberal economic orders to industrial policy-driven models, we must recognize that hydrocarbon-based industrial policy has always existed. It has simply functioned through market-based mechanisms, where economic interests buy political influence within democratic systems. For this reason, I find it difficult to frame the debate as a binary choice between liberal and non-liberal orders. The key issue is how to engineer a global energy transition in a way that is mutually beneficial, rather than disruptive. This requires strategic global institutional design to create a coalition for action. The goal should be to phase out hydrocarbons in a controlled manner, avoiding economic collapse while simultaneously scaling up renewable alternatives.

To me, industrial policy has always been present in one form or another. The real question is whether this policy should be led by individual nation-states, by regional blocs with shared objectives, or by a truly global framework. What worries me most today is that some key global players are turning their backs on multilateral cooperation, largely because their democratic systems have been captured by powerful special interest groups—particularly hydrocarbon lobbies. This is not merely a debate about liberal versus non-liberal governance. Rather, it underscores the critical need for public intervention to counterbalance vested interests and ensure that policy decisions serve the long-term global good.