Please cite as:

van Oosten, Sanne. (2025). “The Importance of In-group Favouritism in Explaining Voting for PRRPs: A Study of Minority and Majority Groups in France, Germany and the Netherlands.” Populism & Politics (P&P). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). January 12, 2025. Doi: https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0046

Please find all replication materials including data, code and appendices here: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/T7G5N

Abstract

The voting behaviour of racial and ethnic minorities is a topic that attracts much speculation, with some claiming that racial and ethnic minorities do vote for Populist Radical Right Parties (PRRPs) and some claiming they do not. In the European Union, where saving data on individual’s race and ethnicity is prohibited, it is very difficult to contribute to these conversations with real facts. Do ethnic minorities and majorities tend to vote for PRRP and what explains their (lack of) support? Thanks to a novel yet costly sampling method, I surveyed racial/ethnic minority and majority voters in France, Germany and the Netherlands and asked them about their propensity to vote for Rassemblement National (RN) in France, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, and Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) in the Netherlands. I compare racial/ethnic minority groups, including Muslims, with majority groups and test the mechanisms that might predict their support for PRRPs. My findings indicate Muslims are among the least likely to vote for PRRPs, though the difference with voters without a migration background is only significant in the Netherlands. When testing what explains the propensity to vote for PRRPs, I find that indicators of in-group favouritism usually explain support to larger extent than out-group hate. Though anti-immigration attitudes predict PRRP voting in all three countries, in-group favouritism explanations explain PRRP voting to a slightly stronger extent. In France and Germany, the ethnocentrism scale predicts voting for RN/AfD more than immigration attitudes do. In the Netherlands, feeling accepted as belonging in the Netherlands explains voting for the PVV the most. Amongst Muslim French, German and Dutch voters, in-group favouritism, or the lack thereof, explains voting for PRRPs as well. French Muslims who feel more attached to France are more likely to vote for RN. German Muslims who do not believe in religious freedom for Muslims are more likely to vote for AfD. This also applies to Dutch Muslims, though immigration attitudes also predict voting for the PVV: the more a Dutch Muslim is against immigration, the more likely they are to vote PVV. Generally, this study makes a case for expanding the standard predictors of PRRP voting towards more indicators of in-group favouritism for the majority in-group, while for Muslims PRRP voting is more driven by policy attitudes. Feeling close or distant towards ethnic in- or out-groups does not predict PRRP voting in any of the cases. These findings contribute to our understanding of PRRP voting in Europe.

Keywords: Populism, Muslims, race, ethnicity, voting behaviour, France, Germany, Netherlands, RN, AfD, PVV.

By Sanne van Oosten (Postdoctoral Researcher at Oxford University, sanne.vanoosten@compas.ox.ac.uk)

Introduction

Political pundits and strategists have long believed that increasing diversity and gender equality would naturally expand the US Democratic voting base, assuming racial and ethnic minorities would reject ethnonationalist extremism in the Republican Party and have nowhere else to turn (Judis & Teixeira, 2002; Skocpol & Tervo, 2020). While this view has been challenged over time (Judis & Teixeira, 2023; Lee, 2008), the 2024 US elections highlighted the complexity of racial and ethnic minority voting behaviour, with racial and ethnic minority voters shifting from Democrat to Republican, though still leaning Democrat (ANES, 2021).

In Europe, studying minority voting behaviour is more challenging due to privacy regulations, yet it remains crucial as the “Replacement Theory” — a conspiratorial claim that immigrants are brought in to vote for political elites — has shaped far-right rhetoric across France, Germany, the Netherlands (Bracke & Aguilar, 2020) as well as the US (Skocpol & Williamson, 2011). Despite this, some pundits suggest that racial and ethnic minorities are increasingly inclined to vote for Populist Radical Right Parties (PRRPs), with figures like Geert Wilders[2] and Donald Trump[3] claiming that Muslim and Black voters support them. However, all of these claims remain underexplored in Europe. This paper investigates whether Muslims and ethnic minorities in France, Germany, and the Netherlands vote differently from their white counterparts, and what factors drive any differences in their voting behaviour.

Answering these questions in the European Union is more difficult than in the US or UK (as shown by the wealth of data in Sobolewska & Ford, 2020). Standard sampling strategies do not yield enough minority participants for statistical analyses (Font & Méndez, 2013). Moreover, strict European privacy regulations limit the availability of sampling frames for racial/ethnic and religious minorities in the European context (Simon, 2017). To overcome these challenges, I surveyed a large sample of Kantar-panellists and used a mini-survey to oversample voters from France, Germany, and the Netherlands with a migration background in Turkey (France, Germany, and the Netherlands), North Africa (France), Sub-Saharan Africa (France), the Former Soviet Union (Germany), Surinam (the Netherlands), and Morocco (the Netherlands). I sampled a high number of minority respondents, with 1889 out of a total N of 3058 respondents having a migration background, of which 649 self-identify as Muslim.

In this paper, I test how likely Muslims or other minority groups are to vote for PRRPs compared to majority groups, and why. I find that Muslim voters are much less likely to vote for the PVV in the Netherlands, though they are just as likely to vote for RN or AfD in France or Germany, respectively. I also explore what predicts the likelihood of Muslims voting for PRRPs. The literature on minority voting is not focused on voting for PRRPs, but explanations vary from issues, belonging and in-group favouritism, or the lack thereof, in this case. I find that issues explain PRRP voting, or the lack thereof, the most amongst the Muslims in France, Germany and the Netherlands.

Amongst majority groups, voting for PRRPs is generally often explained by economic and cultural factors, or their level of education and attitudes towards immigration. In-group favouritism is generally not studied, despite the longstanding evidence that in-group favouritism operates independently from out-group hate (Brewer, 1999). My various indicators of in-group favouritism indeed predict voting for PRRPs more strongly than immigration-attitudes and the impact of level of education disappears when including policy positions and in-group favouritism in the models.

In essence, this research advocates for broadening the conventional factors used to predict PRRP voting to encompass a greater emphasis on affinity towards the dominant in-group. Conversely, among Muslims, PRRP voting tends to be influenced more by policy stances. Whether one feels a sense of closeness or detachment from ethnic in-groups or out-groups doesn’t seem to have any bearing on PRRP voting outcomes in any scenario examined. These discoveries deepen our comprehension of PRRP voting patterns across Europe.

Theory

It has long been believed that increasing racial and ethnic diversity and gender equality would naturally lead to an expansion of the US Democratic voting base (Judis & Teixeira, 2002), as racial and ethnic minorities are put off by ethnonationalist extremism in the Republican Party (Skocpol & Tervo, 2020; Sobolewska & Ford, 2020) and, therefore, have nowhere else to go (Judis & Teixeira, 2002). Though this thesis had been questioned for a longer time (Judis & Teixeira, 2023; Lee, 2008), the most recent US elections drove the point home that reality is more complicated than the “demography is destiny” thesis claims it is[4]: The 2024 US elections saw a significant swing of racial and ethnic minority voters from voting Democrat to voting Republican[5], though the latest most robust data still indicate that the majority of Latinx voters prefer the Democrats[6], just as in 2020 (ANES, 2021). Studying the voting behaviour of racial and ethnic minorities is relatively easy in the US and UK, yet the more stringent privacy regulations in the European Union (EU) make sampling European racial and ethnic minorities more costly and, therefore, rare. In this paper, I use a novel sampling method and study to what extent and why racial and ethnic minority and majority voters in France, Germany and the Netherlands vote for Populist Radical Right Parties (PRRP).

In Europe, the influential conspiratorial “Replacement Theory” claims that immigrants are imported by political elites so they will vote for the political elites who imported them[7][8], as recently propagated by Elon Musk in an effort to promote Trump in the US election campaign[9], this narrative shapes the “demographic imagination”[10] on both sides of the Atlantic. In France, the Great Replacement theory was introduced by writer Renaud Camus in 2011 (Bracke & Aguilar, 2020: 685-686), while similar claims were being made in the US before that (Skocpol & Williamson, 2011: 79-80). Promoted by right-wing figures like Marine Le Pen, it has become central to nationalist rhetoric, suggesting that French culture and identity are at risk due to immigration. This conspiracy theory has influenced political discourse, especially within far-right parties, fuelling xenophobic fears of cultural “submersion.”[11] In Germany, similar views gained traction through the works of Thilo Sarrazin, who claimed that mass immigration would lead to the decline of ethnic Germans. The theory has also been propagated by figures from the Alternative for Germany (AfD), who argue that immigration policies are designed to replace native Germans. Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, populist politicians such as Geert Wilders and the current chair of Dutch Parliament, Martin Bosma, have embraced the theory as well.[12][13][14]

However, pundits and PRRPs also sometimes claim the opposite: that racial and ethnic minority voters are actually very much inclined to vote for PRRPs. For instance, when Geert Wilders’ Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) won the Dutch general elections on November 22, 2023 (van Oosten, 2023b), Geert Wilders gave a speech in which he thanked all of his voters, especially the many Muslims who had voted for him.[15] Pundits weighed in by giving anecdotal evidence of Muslims voting for Wilders.[16][17] Were these claims an effort to legitimize Geert Wilders as a potential prime minister of all Dutch people, or was it really true? Given the lack of research on the voting behaviour of minority groups, these claims remained unsubstantiated.

In summary, the voting behaviour of Muslims, ethnic minorities and immigrant origin individuals is speculated about wildly. As seen above, in an effort to gain perceived legitimacy, some pundits and PRRP leaders will argue minorities vote for them. Conversely, to amplify “demographic anxiety,”[18] PRRP leaders will argue minorities vote for the pro-immigrant Left. So, which one is it? Do Muslims and ethnic minorities in France, Germany, and the Netherlands vote differently than their white majority counterparts? And what drives the differences?

In this theoretical framework, I first discuss the literature on minority voting which is mostly based on policy positions held by minority voters and discrimination they have experienced. Then, I discuss the most frequent explanations of PRRP voting amongst majority groups. I conclude with a discussion about in-group favouritism and how the dynamics of in-group favouritism differ amongst majority and minority groups.

Cultural and Economic Issues as Explanations of Minority Voting

I do not know of any literature on PRRP voting amongst minorities in Europe, though there is literature on the tendency for minorities to vote for left-wing parties. In general, claims that ethnic minority voters vote for Left-wing parties because of their tendency to prefer redistributive policies (Bird et al., 2010: 10–11) have been debunked (Baysu & Swyngedouw, 2020; Bergh & Bjørklund, 2011; Sobolewska, 2006: 206–207; van Oosten et al., 2024e). Cultural issues play a much larger role in explaining voters’ choices than economic issues do (Otjes & Krouwel, 2019: 1159, 1152; Vermeulen et al., 2020: 445, 448). Many of these issues directly influence the way racial and ethnic minority voters see their place in society (Loukili, 2021a, 2021b), and the discrimination that they have experienced (Grewal & Hamid, 2022; Nandi & Platt, 2020; Phalet et al., 2010), or the discriminatory rhetoric they hear coming from politicians on the Right, making them side with the Left, not out of conviction, but out of necessity (Sobolewska & Ford, 2020) or circumstance (Rovny, 2024).

Though racial and ethnic minority voters align with the Left in their views on immigration, integration and Islam, they are less likely to do so on issues such as gender equality (Spierings & Glas, 2022), Lesbian Gay, Bi and Trans (LGBT)-rights (Geurts et al., 2023) and anti-Semitism (Koopmans, 2013). These differences between racial and ethnic minority and majority voters within the Left-wing voting coalition (Sobolewska & Ford, 2020) are used to drive the Left-voting coalition apart (Brubaker, 2017; Farris, 2017; Puar, 2007; van Oosten, 2024e). The general assumption is that racial and ethnic minority voters make the trade-off between aligning with the Left on issues such as immigration, integration and Islam on the one hand, and making compromises on gender and sexuality issues on the other hand (Sobolewska & Ford, 2020). The extent to which this is true, remains under researched, but the rhetoric of this “awkward alliance” (van Oosten, 2025) has influenced political narratives and has rendered party strategists on the Left anxious about how to deal with cultural issues such as gender equality, immigration, and LGBT-rights (Dancygier, 2017; van Oosten, 2022a, 2022b, 2023a).

The awkwardness of the assumed diverse voting coalition of the Left has led to some similar civilisationist forms of nationalism (Brubaker, 2017). Homonationalism, femonationalism, and judeonationalism are examples of these forms of nationalism that instrumentalize vulnerable groups such as women, LGBT individuals, and Jewish people to justify exclusionary practices, particularly against Muslim immigrants. Homonationalism, coined by Puar (2007), refers to the use of LGBT-rights, particularly in Western countries, to contrast “civilised” Western values against perceived intolerance in non-Western groups, particularly Muslims. Femonationalism, introduced by Farris (2017), involves the strategic use of gender equality, often framing Western interventions as a means to liberate women in non-Western countries, such as the justification for the war in Afghanistan.

Homonationalism and femonationalism are not the only forms of civilisationism. For instance, Judeonationalism, recently coined by me (van Oosten, 2024c, 2024d, 2024e, 2024f), refers to the instrumental use of antisemitism to discredit immigrants and justify anti-immigrant rhetoric. Animeauxnationalism (van Oosten, 2024h) is a term I coined to describe the infamous US election campaign quote, ‘they are eating the pets,’ as another form of civilisationism that leverages the idea that racial and ethnic minorities do not believe in animal rights, especially the rights of pets, not so much farm animals, to the same extent as white majorities do. These, and many other, forms of nationalism are often mobilized to promote xenophobia by framing vulnerable groups as symbols of Western values under threat from outsiders, contributing to the marginalization of immigrants and minorities. However, because the literatures on homonationalism and femonationalism are much more developed, I will focus on the impact of these narratives on voting.

Homonationalism first emerged in the Netherlands in 2002 with populist radical right leader Pim Fortuyn, as a response to perceived threats to the country’s liberal values. This was particularly in reaction to Moroccan and Turkish immigrants, coinciding with the Netherlands’ legalization of same-sex marriage in 2000, the first in the world (Brubaker, 2017). This unique context juxtaposed a traditionally progressive stance on LGBT-rights with an alleged Islamic intolerance (Mepschen et al., 2010). In contrast, around the same time, femonationalism gained more traction in the United States, where it was initially used to gather support for the war in Afghanistan by framing it as a mission to liberate oppressed Afghan women (Farris, 2017). This strategic instrumentalization of gender equality has since spread to other Western countries, particularly in Europe (Rahbari, 2021). Meanwhile, Judeonationalism—the use of antisemitism to discredit newcomers—has been especially prominent in Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, and the US, particularly following the Palestine protests in the spring of 2024 (van Oosten, 2024c, 2024d, 2024e, 2024f).

Civilisationism is frequently leveraged during political crises or when national identity is perceived to be under threat, particularly from cultural outsiders (Brubaker, 2017; Farris, 2017; Puar, 2007; van Oosten, 2024c, 2024d, 2024e, 2024f). Conceptual work on these narratives indicates they are primarily elite-driven, top-down efforts aimed at stoking xenophobia, particularly Islamophobia (Khalimzoda et al., 2025), to scapegoat minorities and distract from failing policies (de Haas, 2023). Politicians and media elites, however, frame civilisationist narratives as reactive responses to imminent threats particularly following high-profile acts of violence against women or LGBT-individuals (e.g. Frey, 2020).

Existing research demonstrates that civilisationist rhetoric affects public opinion amongst majority populations (van Oosten, 2022a, 2022b, 2023a), but it remains unclear whether this extends to racial and ethnic minority voters and Muslims. Might views on gender and sexuality impact whether racial and ethnic minority and Muslim voters vote for PRRPs? Or are minority voters more influenced by their views on immigration, integration and Islam?

Indeed, immigration policy and discrimination do impact the everyday lives of racial and ethnic minority voters. Immigration policies play a key role in determining the opportunities for family reunification, while Islamophobia and anti-discrimination laws affect access to the job market, and so on. It is therefore logical that these matters would influence the voting behaviour of racial and ethnic minorities. Furthermore, Muslims endure particularly high rates of discrimination in their day-to-day experiences (Awan, 2014; Fernández-Reino et al., 2023; Mansouri & Vergani, 2018), and witness their inclusion in society be mobilized for electoral purposes (Schmuck & Matthes, 2019: 739). This research will analyse the extent to which racial and ethnic minority voters and Muslims trade-off economic, gender and sexuality-related cultural issues, as well as immigration and Islam-related cultural issues influence voting for PRRPs.

Cultural and Economic Issues as Explanations of Majority Voting

There are two main schools of thought on how to explain why majority groups vote for PRRP: cultural and economic explanations. Just as is the case with minority voters, popular claims that voters are attracted to PRRPs because of economic insecurity instead of cultural issues are largely debunked with cultural issues being the most explanatory of all (Abou-Chadi & Helbling, 2018; Abou-Chadi & Wagner, 2019; van der Brug & van Spanje, 2009). However, economic factors also continue to explain PRRP voting, when the scarcity created by the arrival of immigrants is thrown into the argument.

Although migration experts agree that the economies of receiving countries benefit from immigration (de Haas, 2023; Kustov, 2024), economic challenges and the perceived injustice faced by the populations of receiving countries are often cited as arguments against immigration: whether the argument is that ‘they’ are stealing ‘our’ jobs (Thom & Skocpol, 2020), public services (Cremasci et al., 2024), or housing (Fernández-Reino et al., 2024; Ghekiere & Verhaegen, 2022), material concerns rooted in scarcity lie at the core of the debate. The mobilization of perceived economic injustice has proven to be an effective strategy for attracting voters, with the most recent U.S. elections serving as yet another example.

The US Republican Party now champions the strongest anti-immigration narratives, though this has not always been at the top of the party’s political agenda (Skocpol, 2020). This shift occurred during the Obama-era. His first campaign and term were predominantly focused on healthcare reform (idem). However, beneath the surface, anti-immigration sentiments swelled, with many voters perceiving Obama as a symbol of immigration (idem). While he didn’t, in reality, let more immigrants in than his Republican predecessors, Bush or Reagan (Thom & Skocpol, 2020). Although voters are generally positive about Black politicians (van Oosten et al., 2024a), Obama’s African roots invigorated the Tea Party, a grassroots movement, leading them to turn to immigration as a response to the latent, smouldering old-fashioned racism his presidency stirred (Tesler, 2013).

This puts into question whether concerns over economic issues are not actually concerns over cultural issues, in other words: immigration and racism. Even in the most conservative corners of the US, openly admitting to being racist is stigmatized, prompting many to mask such views (Creighton, 2023). Concerns over economic justice often serve as a justification for racism by pointing to the scarcity of ‘our’ jobs, public services, housing, or whatever scarce economic resource is the challenge of the moment (idem). By invoking these appeals to economic justice, one can pull off xenophobic claims without the stigma attached to more explicit expressions of xenophobia (idem). Putting into question, once again, whether claims of economic injustice are real, or masks to justify anti-immigration views, racism and Islamophobia.

Anti-immigration views and Islamophobia are also not one and the same dimension that can be studied interchangeably. Views towards Muslim predict voting behaviour in the US (Jardina & Stephens-Dougan, 2021; Weller & Junn, 2018). Even those with more positive attitudes towards immigrants are far more critical towards Muslims (Helbling & Traunmüller, 2018), suggesting that discrimination based on religion is much more accepted than discrimination based on ethnicity. The study at hand also sets out to answer whether views towards immigration on the one hand, and Islam on the other impact PRRP-voting differently. This research I am conducting here, will compare and contrast all of these cultural and economic explanations of PRRP-voting for both majority and minority groups. On top of this, I will also include how in-group favouritism compares to the explanations we already know.

The Differential Impact of In-group Favouritism Amongst Minorities and Majorities

According to Social Identity Theory, humans strive towards a positive self-image, and a central strategy to achieve this is in-group favouritism, which is the tendency to prefer members of one’s own group (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). In-group favouritism is an effort to achieve, what Social Identity Theory calls, positive distinctiveness (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), the tendency to seek a favourable comparison of one’s self (positive distinctiveness) through preferring members of one’s own group (in-group favouritism) (Haslam, 2001, 21). Many people mistakenly assume that in-group favouritism is a universal phenomenon, despite the pioneers in Social Identity Theory specifying specific conditions under which this occurs (Tajfel & Turner, 1979: 36). I highlight how individuals can be incentivized to consider alternative strategies to achieve positive distinctiveness without in-group favouritism and the role social status plays in these dynamics.

Social Identity Theory proposes that individuals use three possible strategies to achieve positive distinctiveness: individual mobility, social creativity, and social competition. The choice of strategy depends on various factors such as the group’s social status, belief in social mobility or change, the permeability of group boundaries, perceived security of group relations, and the perceived homogeneity/heterogeneity of the out-group.

Low-status groups, such as racial and ethnic minority or Muslim voters, can use the three strategies to achieve positive distinctiveness in different ways. Some groups may perceive their boundaries as permeable, for instance because they have a name or appearance that makes them pass as part of the high-status out-group. This could be the case amongst German citizens with a migration background in the Former Soviet Union or Maghrebi French with fair skin and a French name. If that is the case, they will be likely to strive for individual mobility to join the high-status group, leading to out-group favouritism through accepting the out-group’s superiority. Other groups may perceive their boundaries as impermeable, possibly due to having an ethno-racially distinct name or black skin. This may be the case amongst citizens with a migration background in Turkey or French citizens from Sub-Saharan Africa. In that case, boundaries are impermeable. If group relations are seen as legitimate and stable, individuals will try to achieve positive distinctiveness through social creativity by redefining the dimensions of group comparison or attributing different meanings to current comparative dimensions (Haslam, 2001: 25), think of Muslim women in Europe countering common stereotypes of themselves as complacent and docile (van Es, 2019). This redefinition of group membership coincides with avoiding a direct challenge to the out-group’s superiority. If group boundaries are perceived as impermeable and status differences as illegitimate and/or unstable, low-status groups are more likely to choose social competition, leading to direct and open in-group favouritism (Haslam, 2001: 25), also known as “fighting fire with fire” in the case of Muslim voters voting for a political party advocating for and run by Muslims in the Netherlands, DENK (Loukili, 2021a, 2021b). In summary, not all low-status groups favour their in-group.

For high-status groups, the same three strategies exist, but they always lead to in-group favouritism. If group boundaries are perceived as permeable, high-status groups expect low-status groups to exert individual mobility and join them. If not, high-status groups may argue that low-status groups are guilty of causing their own inferiority. If group boundaries are perceived as impermeable, legitimate, and stable, high-status group members may exhibit “magnanimity” while engaging in latent discrimination and covert repression (Haslam, 2001: 26), which may be the case amongst high-status groups claiming to be colour-blind (Tiberj & Michon, 2013). If a high-status group perceives group relations as unstable and threatening, they may resort to “supremacist ideologizing, conflict, open hostility, and antagonism” by directly promoting the out-group’s inferiority (Haslam, 2001: 26), as is the case with some members of populist radical right parties (Kešić & Duyvendak, 2019; Kortmann, Stecker, & Weiß, 2019). For high-status groups, all strategies lead to in-group favouritism, as already demonstrated for voting behaviour (Nadler et al., 2025; van Oosten, 2024g).

Comparing France, Germany, the Netherlands and their PRRPs

I conducted this research in France, Germany and the Netherlands, three countries with key differences. In France, there is a strong emphasis on citizenship, secularism and a strong division between church and state, there are no religious parties in the political landscape of France (Kuru, 2008). In Germany, Christian political parties have had a longstanding presence (Schotel, 2021) and the approach towards Muslims is characterized by the history of integration of guestworkers (Yurdakul, 2009). The Netherlands has a host of PRRP and Christian parties in Parliament (Kešić & Duyvendak, 2019), and a history of guest workers from Turkey and Morocco and immigrants from former colonies such as Surinam and Indonesia (Vermeulen et al., 2020). All three countries have a history of parliamentarians from mainstream and PRRPs espousing Islamophobic rhetoric, with France and the Netherlands having a longer and more vociferous history of PRRPs and Germany being relatively new to the game and taking on a comparatively less strident tone (Brubaker 2017).

In France, secularism (laïcité) tends to frame debates on Islam more than in Germany and the Netherlands (Kuru, 2008). For decades, French discussions on the headscarf have more often been related to religious neutrality of the state than to gender equality (Korteweg & Yurdakul, 2021). Although Marine le Pen, leader of France’s PRRP Rassemblement National (RN) mixes civilisationist weaponization of gender equality and LGBT-rights with Christian conservatism championing traditional gender roles and the abolition of marriage equality (Scrinzi, 2017: 5; Snipes & Mudde, 2020: 455–456), gay French voters are still attracted to RN more than their straight counterparts (Dancygier, 2017: 188). Nevertheless, the supposed binary between gender equality/LGBT-rights on the one hand and Islam on the other remains a powerful civilisationist argument against Islam in France (Brubaker, 2017: 1201; McGlynn, 2020).

In Germany, the first Populist Radical Right Party (PRRP) emerged relatively late in the Bundestag, compared to France and The Netherlands (Albertazzi & Mcdonnell, 2008; Althof, 2018). Germany has relatively conservative policies on homosexuality, such as not yet adopting marriage equality (Schotel, 2021). Germany’s PRRP Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has a more conservative Christian nature and following than their French and Dutch counterparts. AfD propagates traditional gender roles and opposition to marriage equality and to homosexual couples adopting children (Althof, 2018: 341), although examples of German homonationalist rhetoric do exist (Ayoub, 2019: 25). The rare instances of a civilisationist backlash against Islam are more often framed in feminist than homonationalist terms (Choi et al., 2021; Dancygier, 2017: 188).

The Netherlands is considered the most striking example of a country that uses civilisationist rhetoric in combating Islam (Brubaker, 2017: 1194). While France and Germany’s PRRPs need to navigate between civilisationist rhetoric and courting of conservative Christians (Marzouki et al., 2016), Dutch PRRPs have not been nearly as inhibited by constraints posed by conservative Christian electorates. Therefore, the weaponization of gender equality and LGBT-rights in combating Islam are more common, more ingrained and more virulent than in France and Germany (Brubaker, 2017: 1193–1197; Mepschen et al., 2010). Islamophobia is by far the highest in The Netherlands, compared to France and Germany (Heath & Richards, 2019: 29). Nonetheless, of the three countries, the Netherlands is the only one to recognize Islam as a state religion (Saral, 2020: 5).

The electoral systems of France, Germany and the Netherlands could help explain the different flavours of PRRPs we see in the three countries. Germany knows mixed-member proportional representation, with a first vote for a direct candidate of their constituency and a second vote for a party list. The threshold of five percent for a political party to enter the Bundestag and elements of a single-member district system and the sizable Christian population make it necessary to court conservative Christian voters, partially explaining why AfD chases conservative Christians in the way they do.

France belongs to a completely different family of voting systems with single-member districts and a two-round runoff for national elections, making it even more necessary for new parties to enter politics with a broad coalition of voters. Despite France’s strong history of secularism, exacerbating civilisationist rhetoric, RN needs to woo conservative Christian electorates in order to make it first past the post. This means that civilisationist rhetoric is less likely to be visible.

The Netherlands knows party list proportional representation and a very low voting threshold: a mere one seat in parliament. This system allows for many parties who each have their own flavour of populism and Christian conservatism separately. Indeed, the Netherlands has four PRRPs in parliament at the time of writing and three separate Christian parties as well. Dutch PRRPs are therefore less likely to need to court Christian conservatives. This explains, in part, why civilisationist rhetoric pitting Dutch secular liberal values against a regressive Islam did not need to be combined with pursuing Christian conservative voters as much as we see in France and Germany, making Dutch civilisationism “strikingly” (Brubaker, 2017: 1194) different and all the more virulent.

Methods

I oversampled respondents with specific migration backgrounds to make group-specific statistical inferences (Font & Méndez, 2013: 48) and chose minoritized groups: numeric minorities that state experiencing discrimination to the largest extent (FRA: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2017: 31). In France, the oversampled groups of ethnic minority citizens consist of French citizens with a North-African (Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria), Sub-Saharan African (Niger, Mauritania, Ivory Coast, French Sudan, Senegal, Chad, Gabon, Cameroon, Congo) and Turkish background. In Germany, I oversampled German citizens with a Turkish and Former Soviet Union (FSU) background. In the Netherlands, I oversampled Dutch citizens with a Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese background. Some groups have come to France, Germany or the Netherlands as a result of the colonial ties between host and home country, some came as guest workers (FRA: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2017: 93). I also oversampled French citizens with a Turkish background and German re-migrants from the FSU. Some, but not all, of the oversampled migration backgrounds are countries with Muslim-majority populations (Phalet et al., 2010; Verkuyten & Yildiz 2009; Dangubić et al., 2020), making it possible to disentangle whether effects are either religiously or ethnically/racially driven.

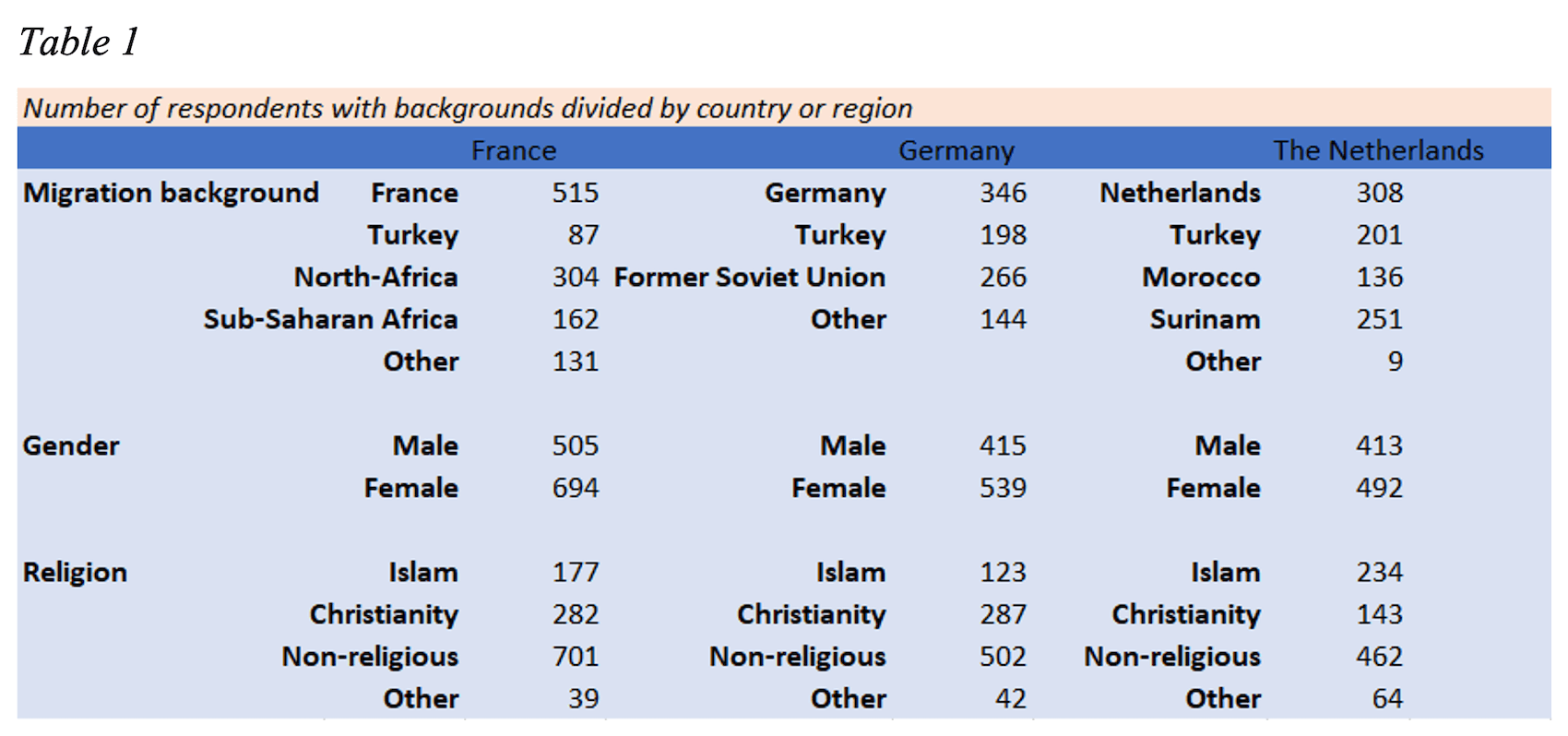

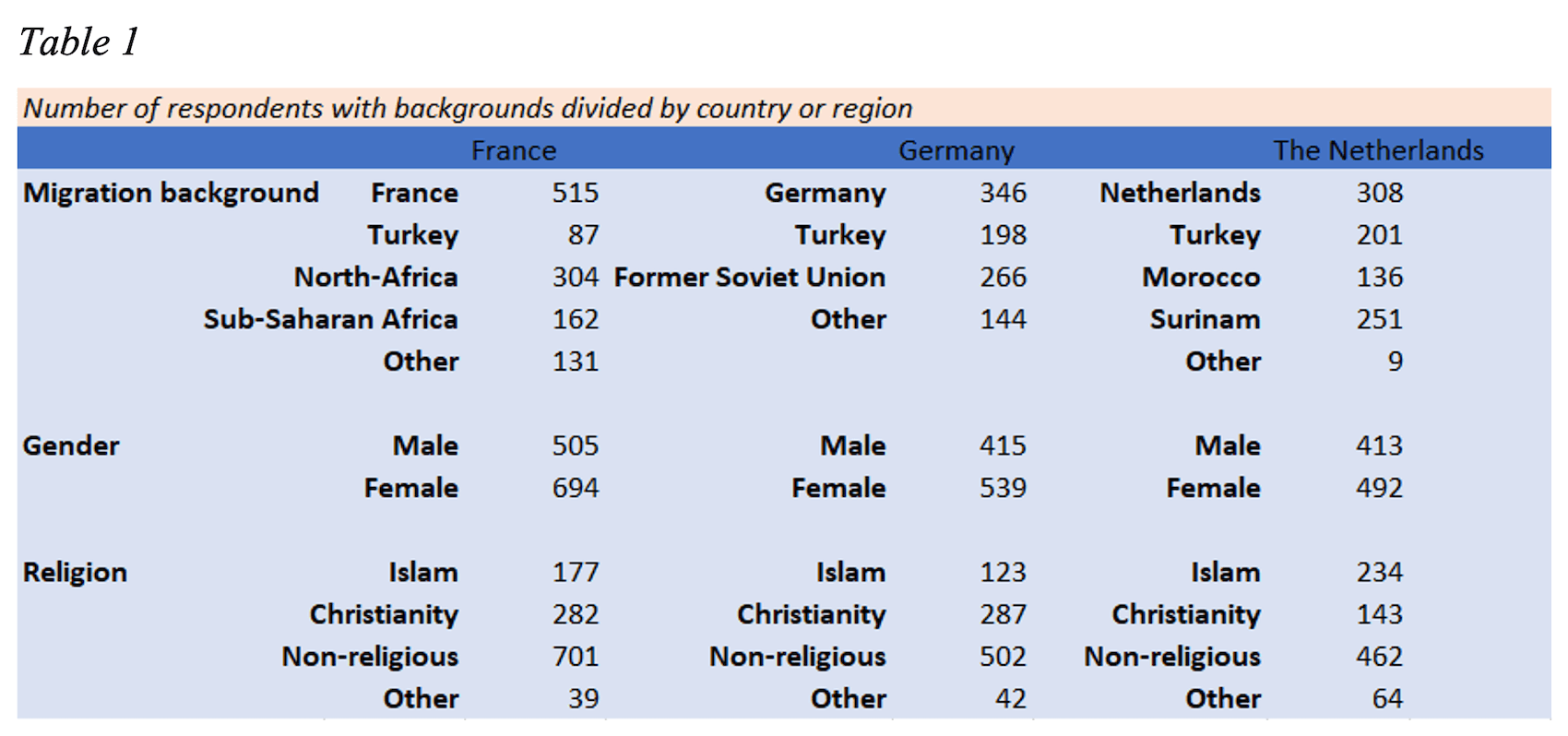

After running pilots and obtaining the ethics approval, see Appendix, I gathered data between March and August of 2020 and surveyed 3.058 citizens of France, Germany and the Netherlands, administered by survey agency Kantar Public. One important challenge in surveying ethnic/racial minority groups comes from the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a European law legally restricting saving data on race and ethnicity (European Commission, 2018). I overcame this challenge by employing a large-scale filter question to the representative Kantar-panels in all three countries. I asked a very large sample to participate in a mini survey. The first and only question of this mini survey asks where their mother and father were born. If either one of their parents were born in a country of origin I wanted to oversample, we redirected this respondent to the full survey. If not, we either terminated the survey or redirected a small percentage to the full survey. This enabled me to form sizable groups of minority citizens for my final survey, ensuring ample diversity, a feature so often missing from survey research (Coppock & McClellan, 2018; Krupnikov & Levine, 2014; Mullinix et al., 2015). Though there is still a chance of selection bias, I have variables to weight the data on gender, migration background, education, age, urbanization and region, and the findings are broadly the same with and without weights. All data, survey questions, information about the sampling strategy implemented, pre-registration details, and ethical review documentation can be found on Harvard Dataverse for France (van Oosten et al., 2024b), Germany, (van Oosten et al., 2024c) and the Netherlands (van Oosten et al., 2024d). I ended up with the following number of respondents in each group:

I asked all respondents about their ethnic and religious identification. For ethnic identification I asked: “In terms of my ethnic group, I consider myself to be… (max. 2 answers).” I presented the respondents a list of 13 answer categories, including French, German, Dutch, Turkish, Maghrebi, Yoruba, Former Soviet Union, Kazakh, Moroccan, Surinamese, and Hindustani, see the full list on Harvard Dataverse (van Oosten et al., 2024b, 2024c, 2024d). The last questions of the survey were about religious identification. I asked: “Do you consider yourself as belonging to any particular religion or denomination?” If the respondent answered yes, I followed up with “Which one?” allowing respondents to answer “Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Jewish, Other, [specify].” Respondents were able to indicate that they identified with a max of two ethnic groups, of which one could be French, German or Dutch and one religion. Table 1 shows the exact number of each group of respondents based on their migration backgrounds, and the percentage of which identified as Dutch, an ethnic minority group or belonging to a religion.

For each ethnic group and religion respondents selected, the respondents then received a list of four statements with answers ranging from 0 (disagree) to 10 (agree), which together form an ethnic in-group favouritism scale (Bizumic et al., 2009). Respondents received this battery of four statements between zero and three times, depending on how many ethnic or religious groups they identified with. I measured levels of ethnic and religious in-group favouritism on a scale from 0 to 10. I asked respondents to answer the following questions:

- In general, I prefer doing things with [ethnic or religious group] people.

- The world would be a much better place if all other groups are like [ethnic or religious group] people.

- I don’t think it is good to mix with people from other groups.

- We should always put [ethnic or religious group] interests first and not be oversensitive about the interests of others.

I conducted principal component analysis and the Chronbach Alpha for the ethnic scale was 0.87 and for the religion scale it was 0.80.

I measured issue stances in both the cultural and economic dimensions, split into eight issues: taxing the rich, social benefits, climate change, fuel prices, immigration, Islam, equal pay for men and women, and Lesbian, Gay, Bi (LGB, I did not measure attitudes towards trans rights)-rights. I standardized all independent variables to run from 0 to 1. For the exact measurements of issues, belonging in the Netherlands and experiences with discrimination, age, gender and level of education, see the full list of survey questions on Harvard Dataverse (van Oosten et al., 2024b, 2024c, 2024d).

As the dependent variable, I measured propensity to vote (PTV) for RN, AfD and PVV by asking respondents: “Please indicate the likelihood that you will ever vote for the following parties. If you are certain that you will never vote for this party then choose 0; if you are certain you will vote for this party someday, then enter 10. Of course, you can also choose an intermediate position” (as formulated in LISS, 2018). I also measured the PTV for all other parties in parliament at the time of gathering data, see the data and appendix on Harvard Dataverse (van Oosten et al., 2024b, 2024c, 2024d).

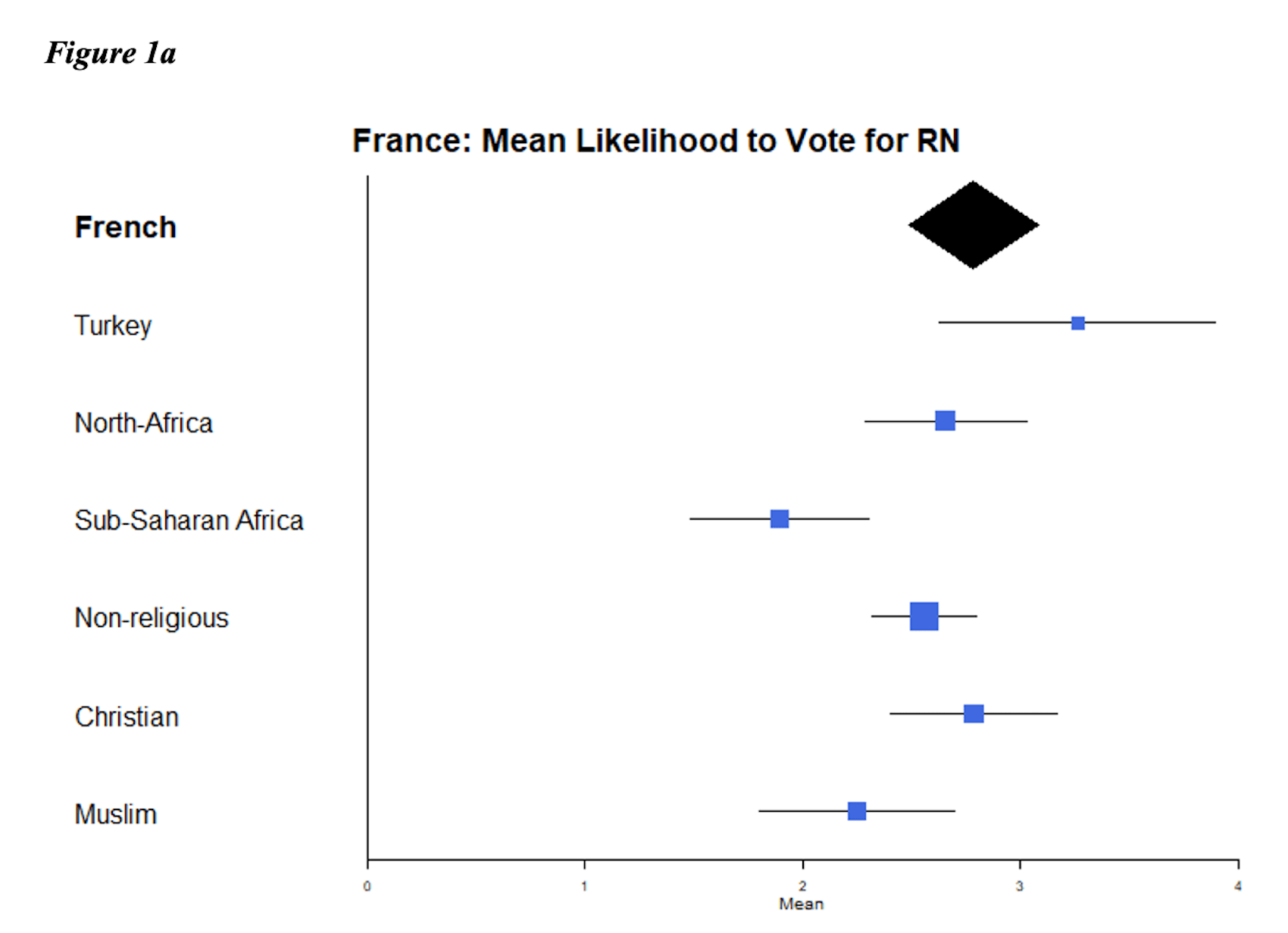

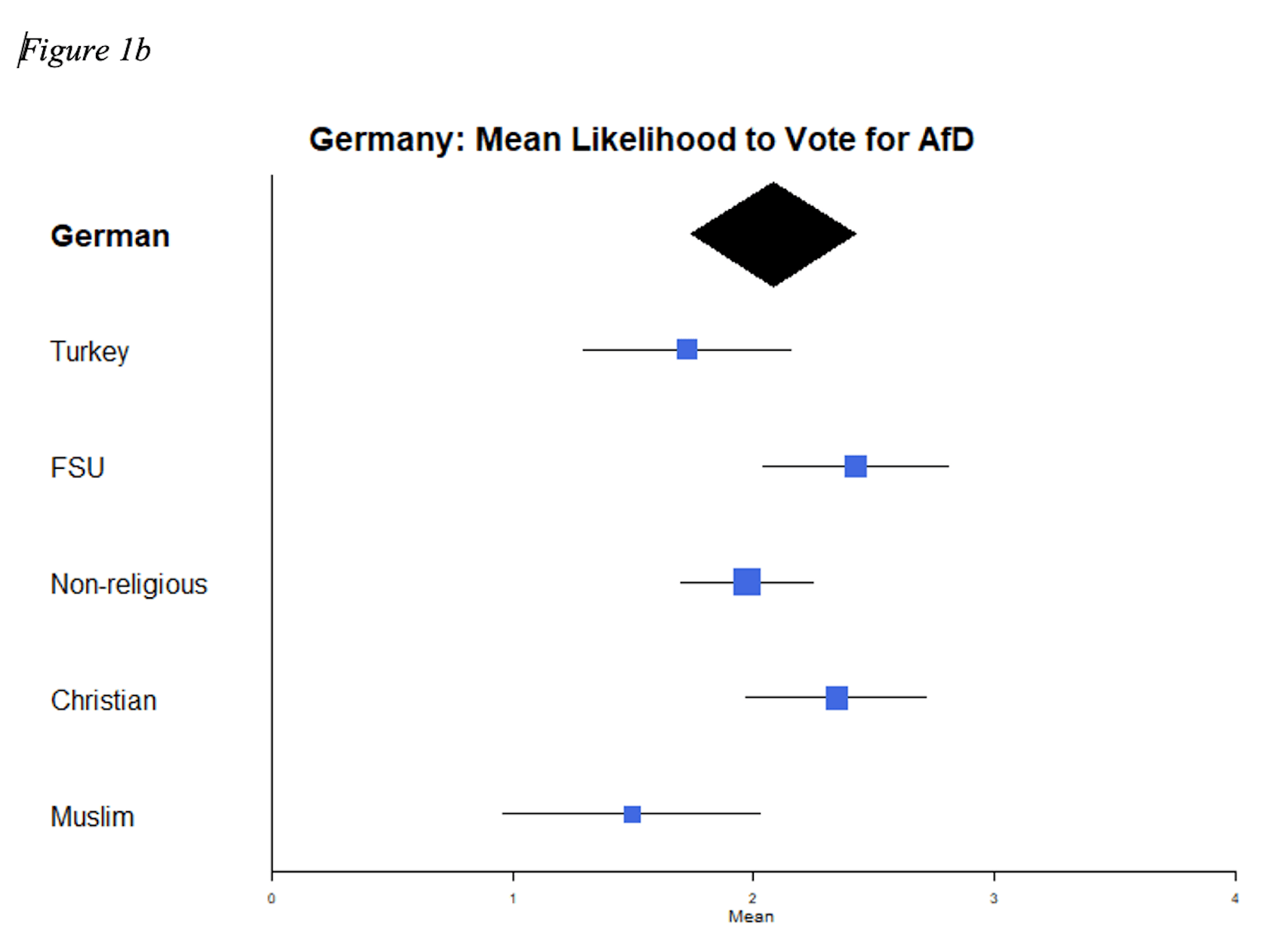

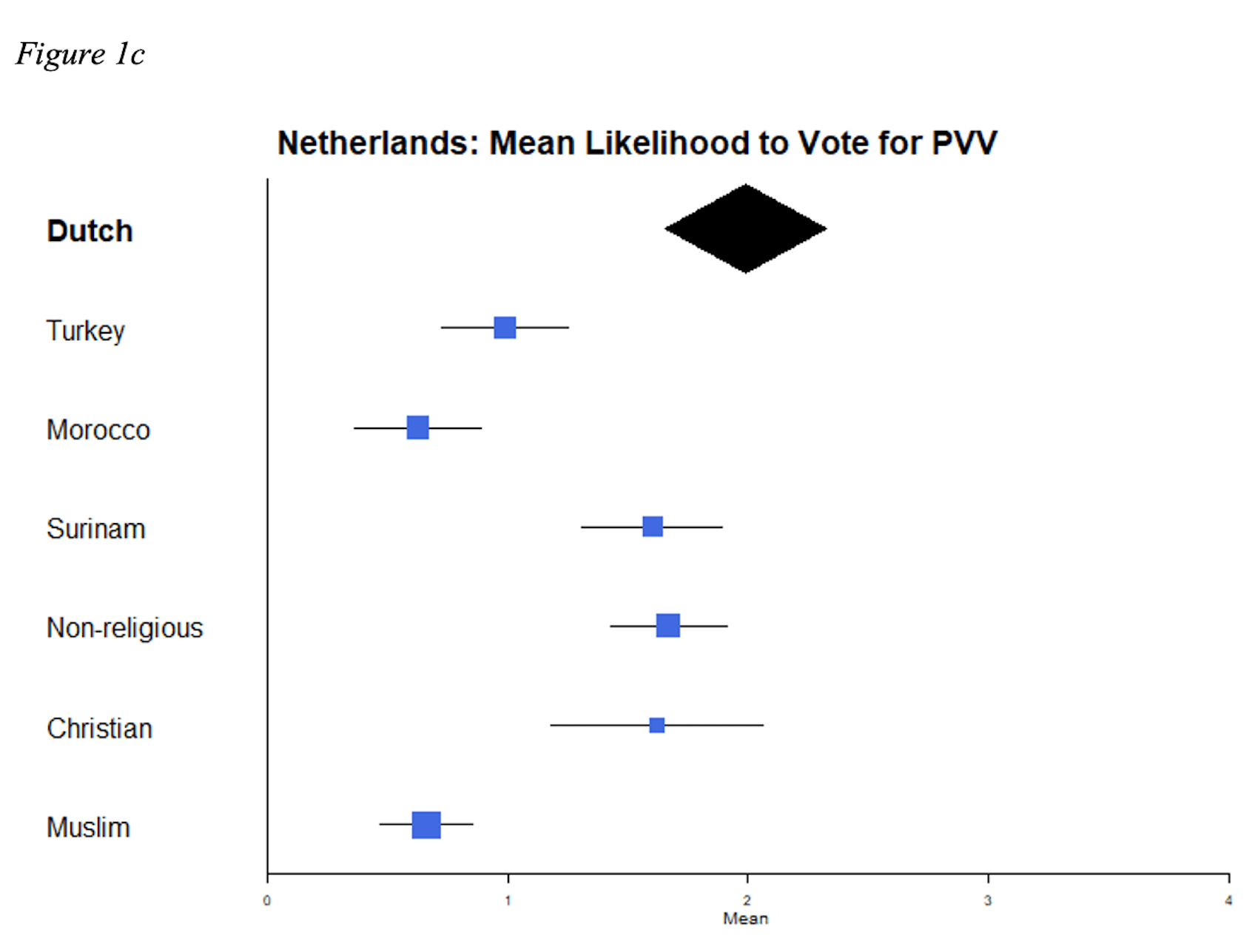

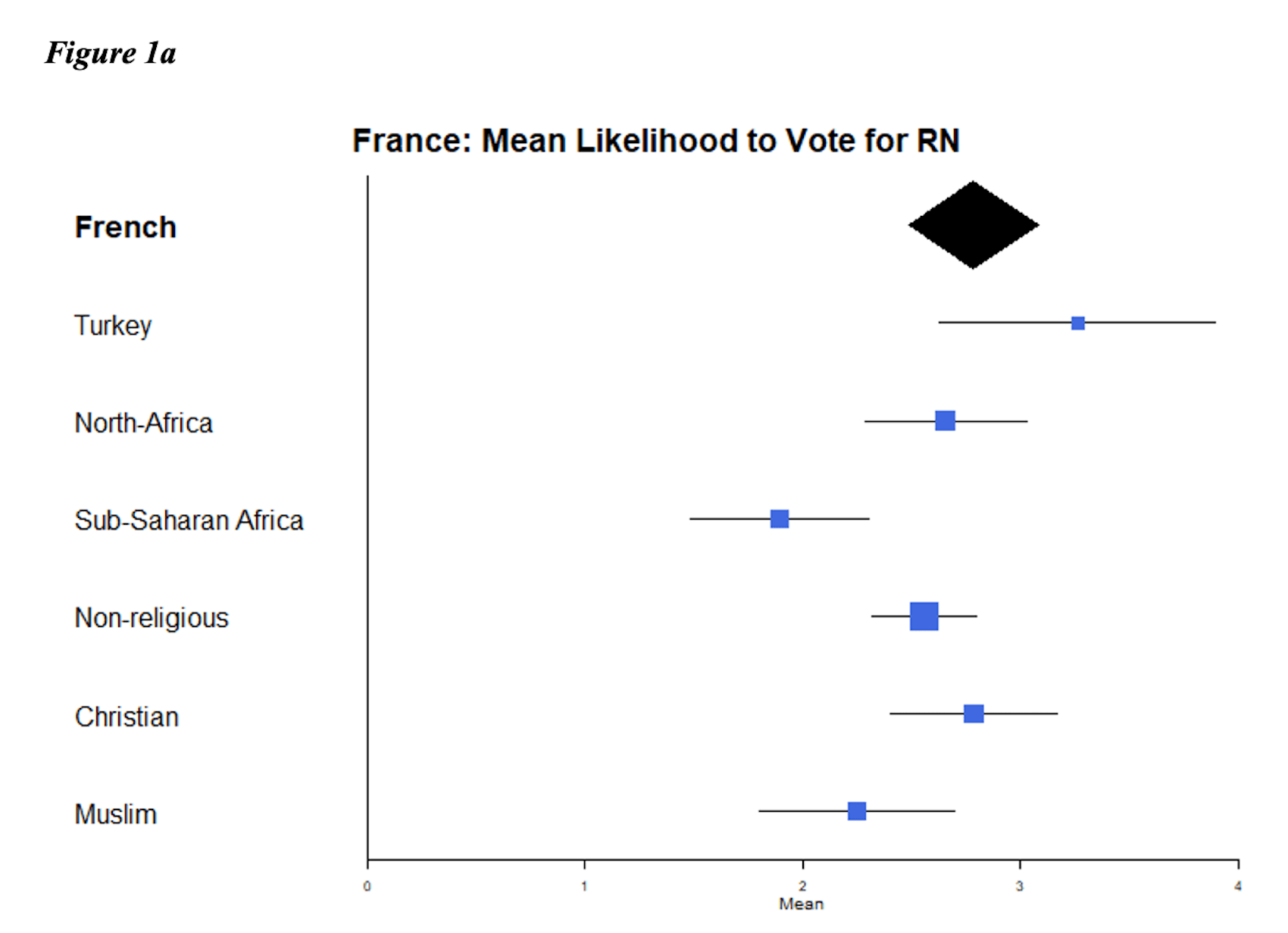

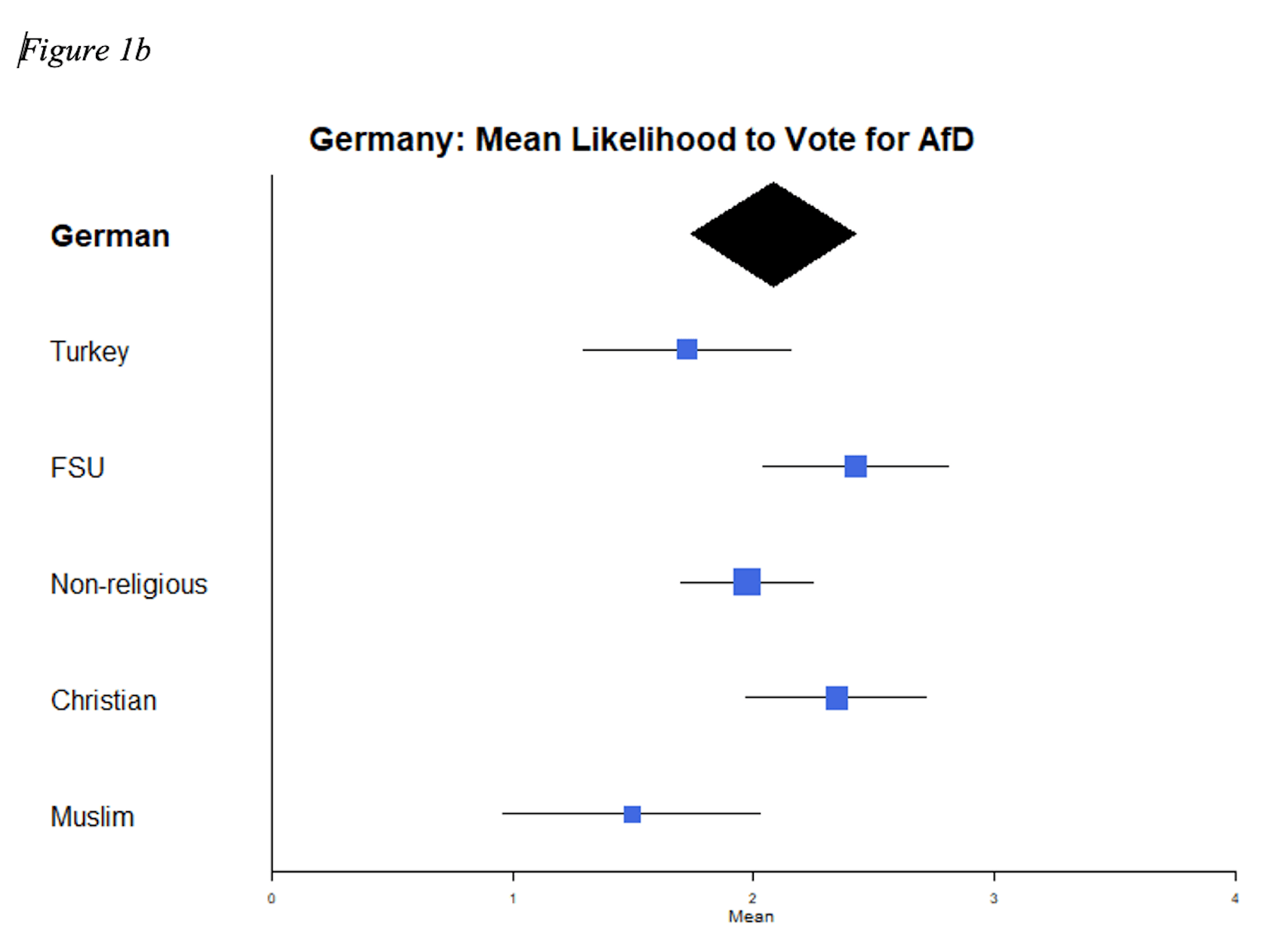

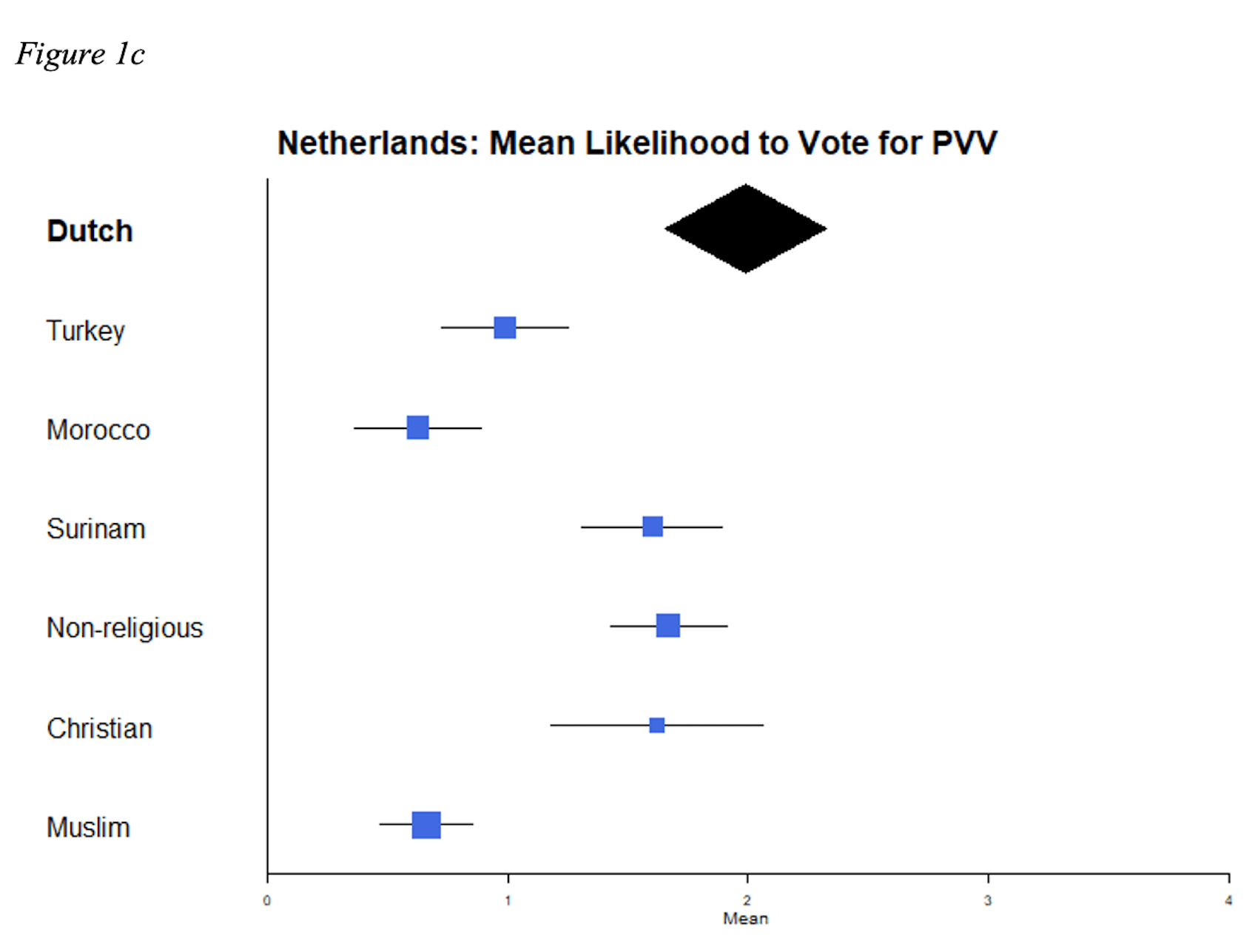

In figure 1a, 1b, and 1c, I analyse and present the data using marginal means where I compare different subgroups because I wish to avoid confusing readers with different reference categories (Leeper et al., 2020). I present marginal means of PTV-scores for all racial, ethnic and religious groups sampled separately. I do not use weights. I ran robustness checks with weights for the general population and didn’t find differences between the outcomes with and without weights, see code. Weighting the data for the minority and majority groups separately is impossible because France and Germany do not have population data of educational attainment, gender, age, urbanization, or region of ethnic minority and majority citizens, let alone Muslims. I analyse the underlying mechanisms using linear models. I prepared the data using R-package “tidyr” (Wickham, 2020), analysed it using linear models with R-base, and visualized it with R-package “ggplot2” (Wickham et al., 2020).

Findings

Intergroup Voting Differences

How likely are the racial, ethnic and religious groups to vote for PRRPs? In Figure 1a, I present the mean PTV-scores of RN in France and show that voters with a Turkish background in France are most inclined to vote for RN, followed closely by Christian and non-migrant French voters. Conversely, Muslims exhibit the lowest likelihood of supporting RN, significantly less than Turkish-background voters. In Figure 1b, I present the mean PTV-scores of AfD in Germany and show that voters from the Former Soviet Union are most likely to support AfD, with no significant difference in Muslim voters’ likelihood to support AfD compared to other groups. Finally, in Figure 1c, I present the mean PTV-scores of PVV in the Netherlands and find that Dutch voters without a migration background are most inclined to vote for PVV, while Muslim, Turkish, and Moroccan voters are significantly less likely to support PVV compared to other groups, with Muslims showing the lowest likelihood.

Based on Figure 1a, voters with a background in Turkey are the most likely to vote for RN in France, with a score of 3.26 (SD = 0.34). This is closely followed by Christian voters, with a score of 2.78 (SD = 0.19), and French voters without a migration background, with a score of 2.78 (SD = 0.30). Voters with a background in North Africa come next, scoring 2.66 (SD = 0.37), followed by non-religious voters, scoring 2.56 (SD = 0.24). Muslims have the lowest likelihood of voting for RN, scoring 2.25 (SD = 0.45). When considering confidence intervals, there is overlap between all groups except for voters with a background in Turkey and Muslims. This suggests that the difference in voting likelihood between only these two groups is statistically significant, indicating that voters with a background in Turkey are more likely to vote for RN than Muslims in France. Although the group of French citizens with a background in Turkey is small (N=87) and mostly secular. It is important to note that Muslims are just as likely to vote for RN as non-religious and Christian voters, as their confidence intervals overlap with those groups. This suggests that there’s no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of Muslims voting for RN compared to non-religious or Christian voters in France.

In the German case, voters with a background from the Former Soviet Union (FSU) are the most likely to vote for AfD, scoring 2.42 (SD = 0.39). This is followed by Christian voters, with a score of 2.34 (SD = 0.37), and German voters without a migration background, scoring 2.08 (SD = 0.34). Non-religious voters come next, scoring 1.97 (SD = 0.27), while voters with a background in Turkey score 1.72 (SD = 0.43). Muslims have the lowest likelihood of voting for AfD in Germany, scoring 1.50 (SD = 0.53). Notably, there is no significant difference between Muslims’ likelihood to vote for AfD and any other group, as the confidence intervals for all groups overlap. This suggests that there is no statistically significant difference in voting likelihood between these groups when it comes to supporting the AfD in Germany.

In the Netherlands, Muslim, Turkish, and Moroccan voters are significantly less likely to vote for PVV (Party for Freedom, Partij voor de Vrijheid) compared to non-religious voters and Dutch voters without a migration background. Dutch voters without a migration background have a score of 1.99 (SD = 0.33), followed by Surinamese voters at 1.60 (SD = 0.29), non-religious voters at 1.67 (SD = 0.24), and Christian voters at 1.62 (SD = 0.24). Turkish and Moroccan voters have lower scores, 0.99 (SD = 0.26) and 0.63 (SD = 0.13) respectively, while Muslims have the lowest likelihood of voting for PVV, scoring 0.66 (SD = 0.20).

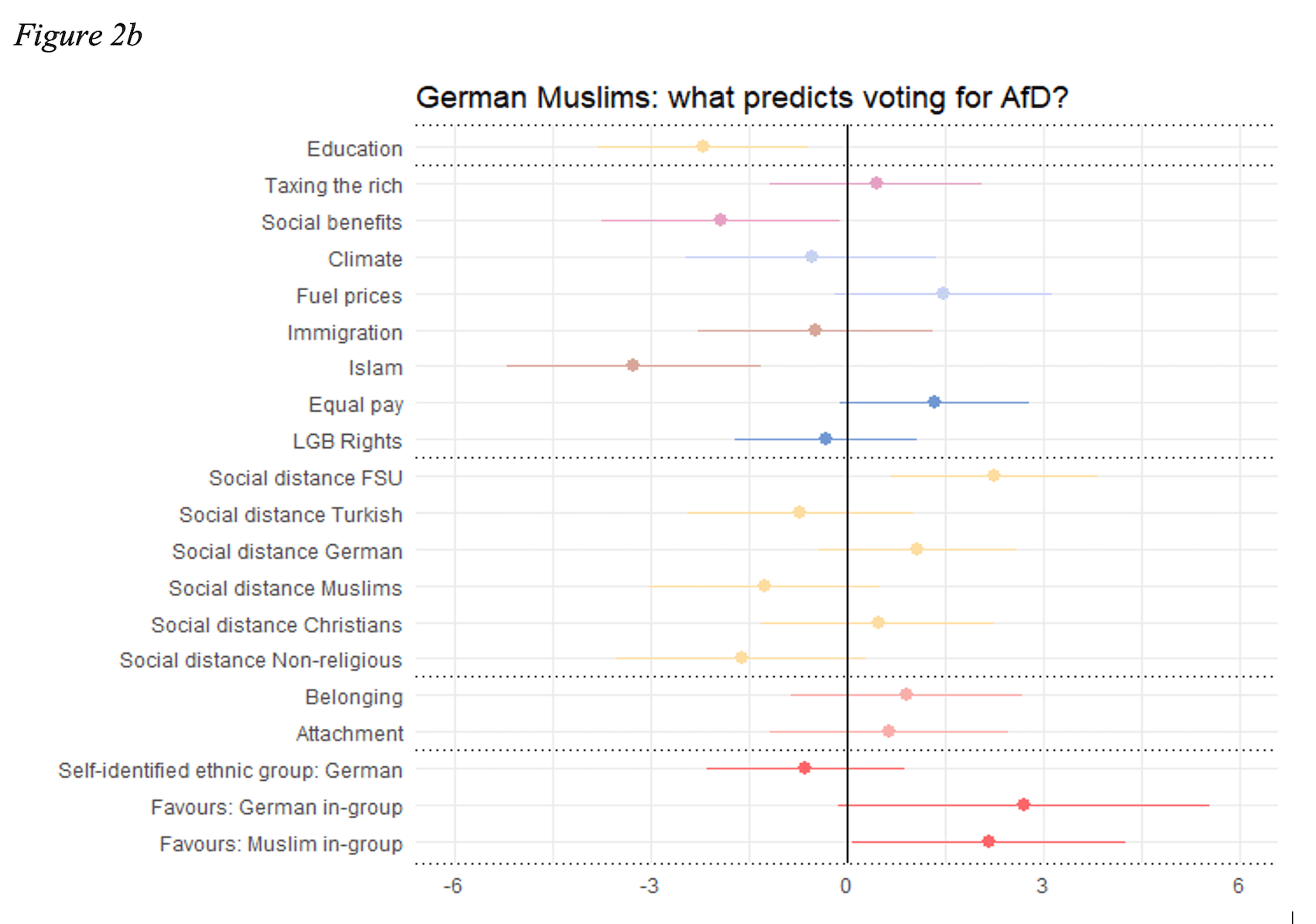

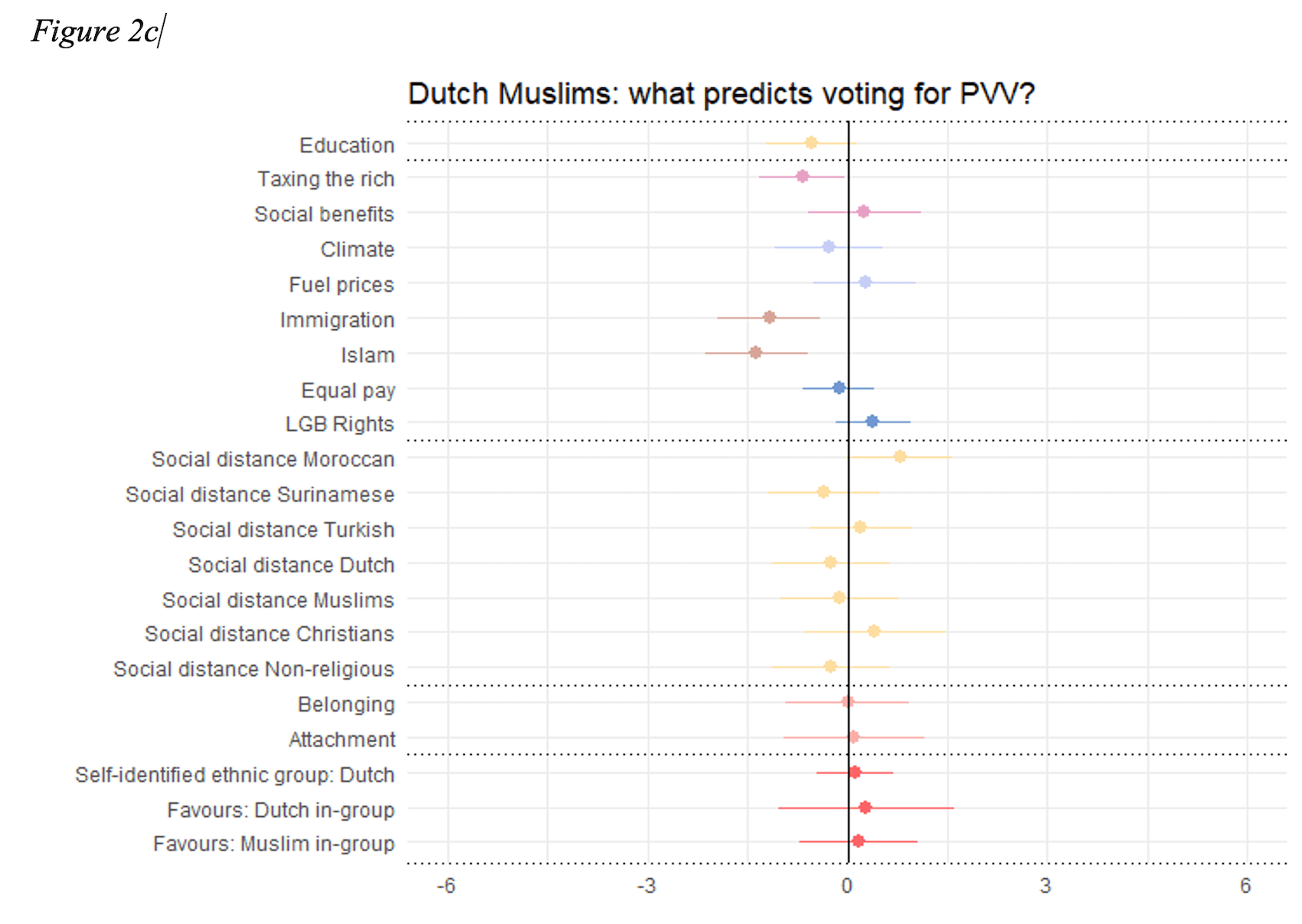

What Explains PRRP Voting Amongst Muslims?

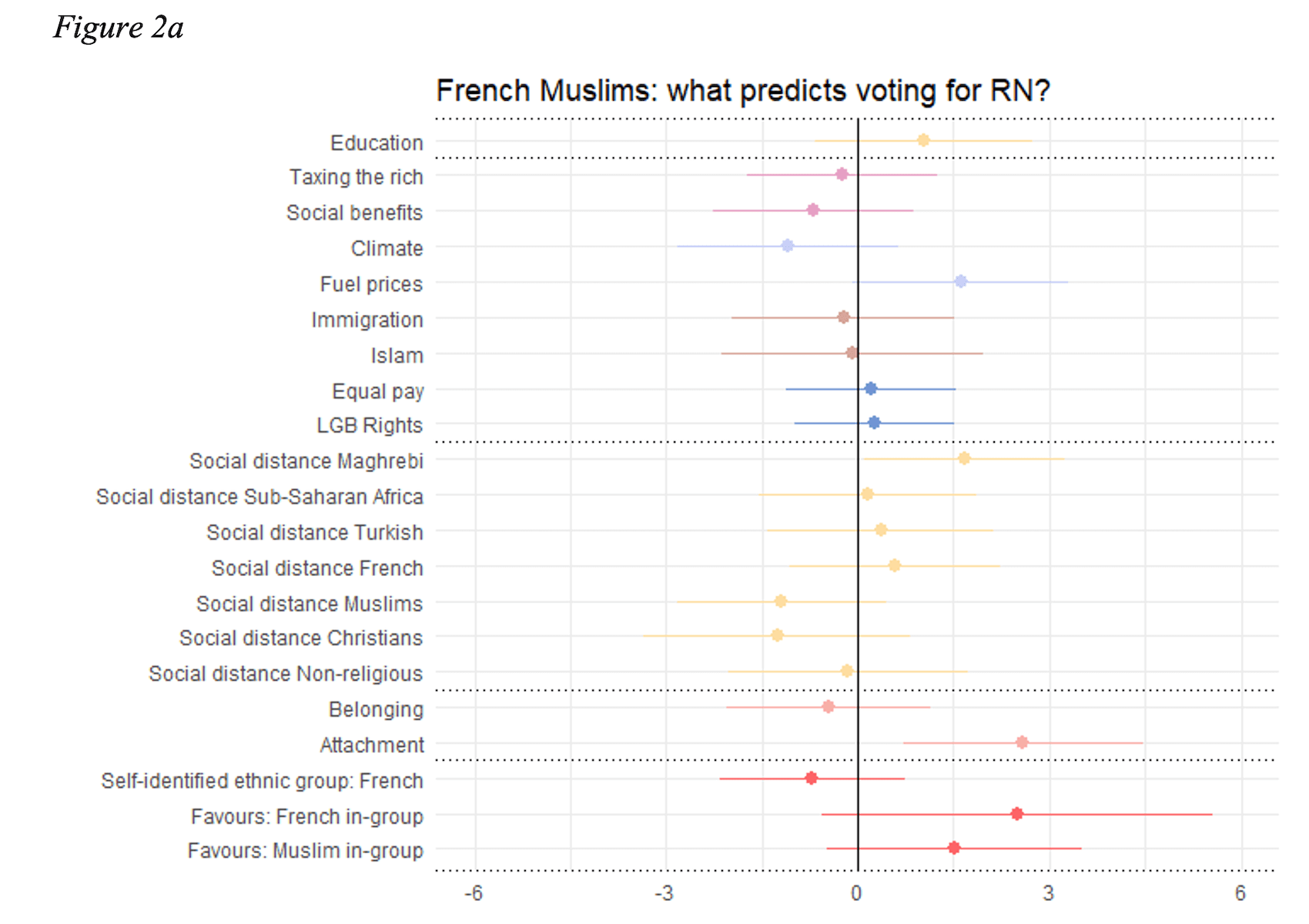

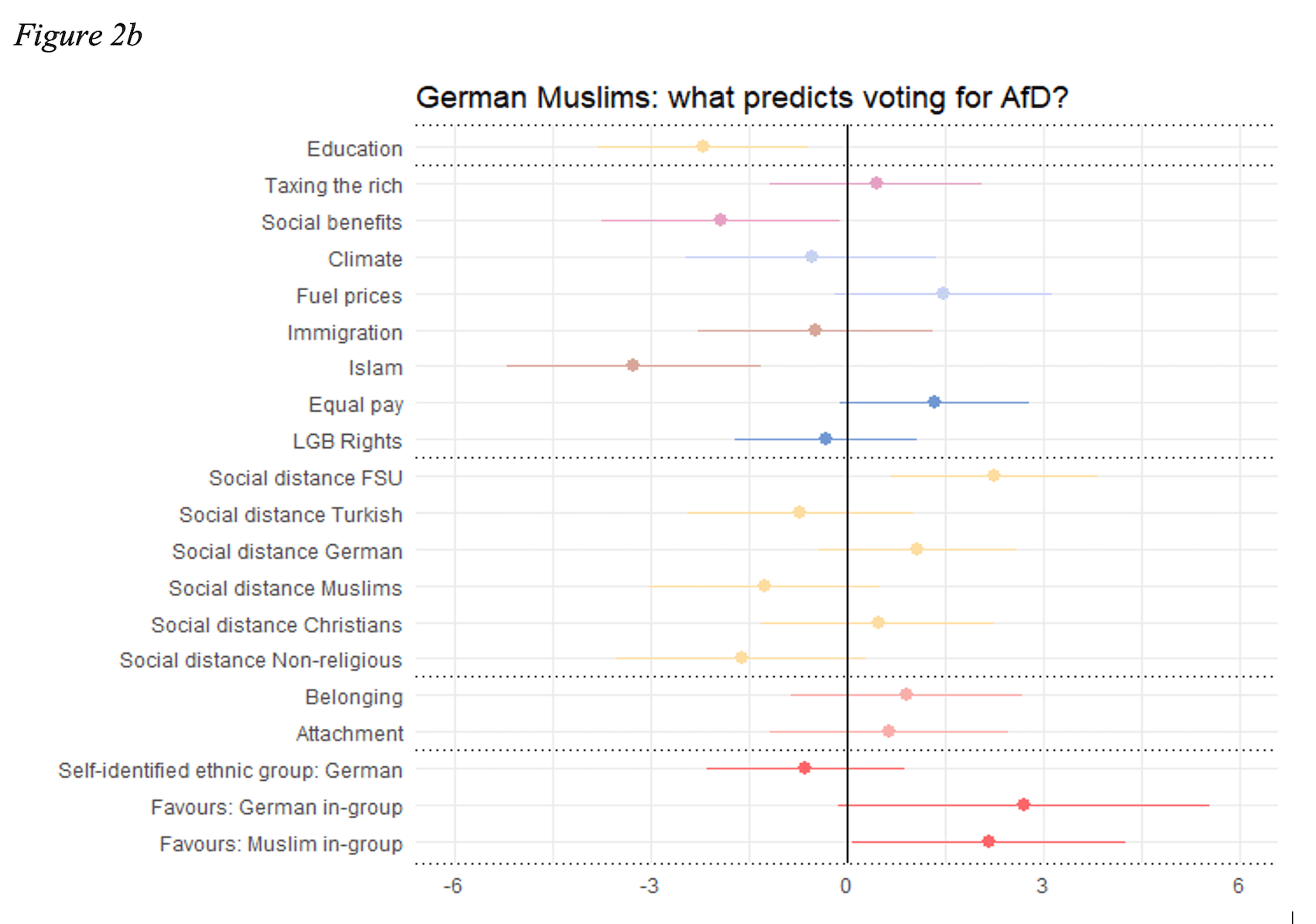

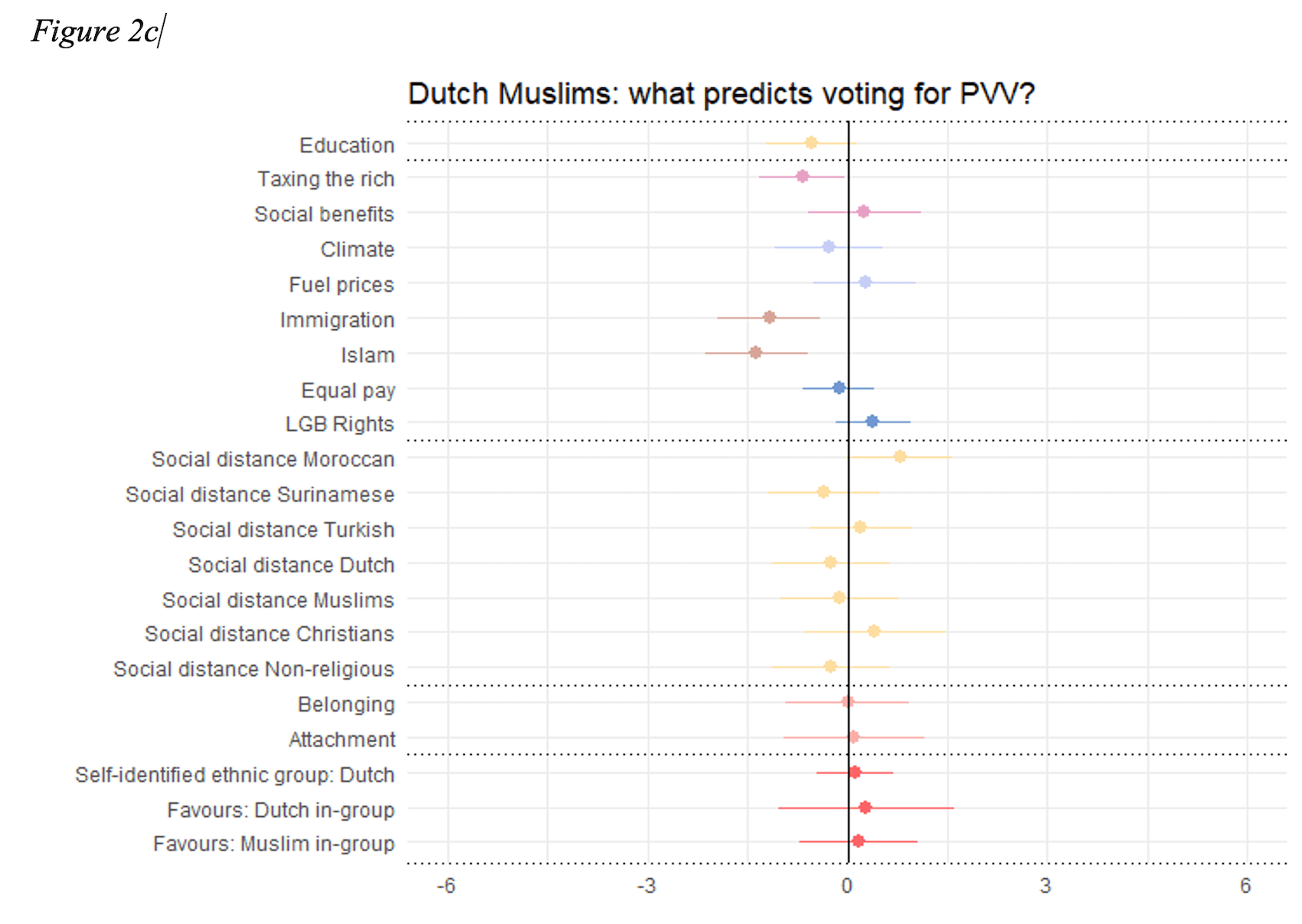

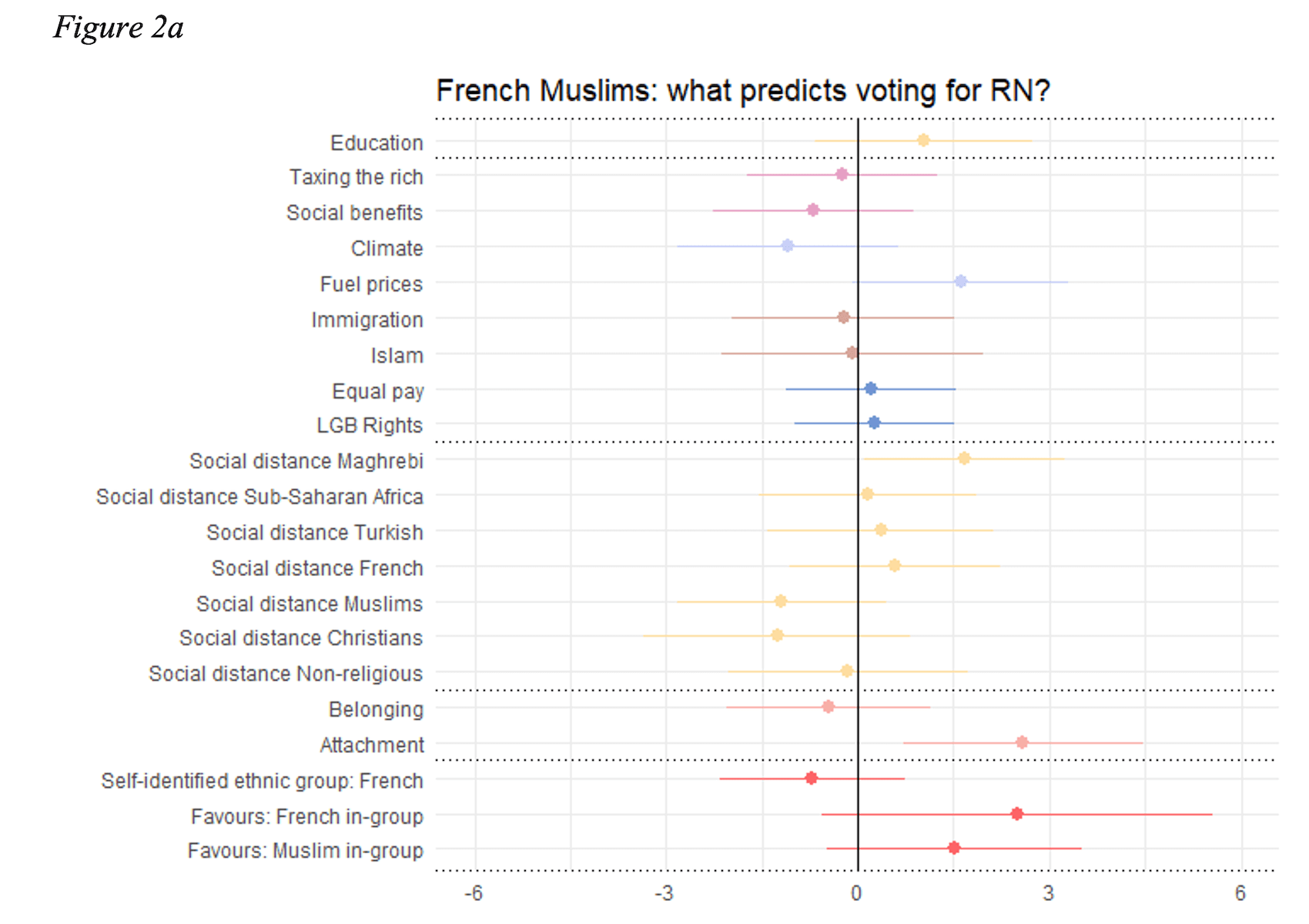

Figure 2a, 2b, and 2c provide insights into the factors influencing the voting behaviour of Muslims in France, Germany, and the Netherlands regarding PRRPs. In France, attitudes towards fuel prices, social distance towards Maghrebi individuals, and attachment to France significantly impact voting for RN. In Germany, level of education, attitudes towards social benefits, Islam, perceived social distance towards FSU individuals, and in-group favouritism towards Muslims are significant predictors of AfD support. In the Netherlands, attitudes towards taxing the rich, immigration, and Islam, along with social distance from Dutch Moroccans, influence the likelihood of voting for PVV among Dutch Muslims.

What predicts whether French Muslims vote for RN? The adjusted R-squared for the model is 0.08931. Among the predictors, significant variables include the perceived social distance towards the ethnic minority group Maghrebi (Estimate = 1.67036, p-value = 0.03644), and attachment to France (Estimate = 2.58745, p-value = 0.00703), indicating that these factors have a significant impact on predicting whether French Muslims vote for RN. However, other variables such as education, taxing the rich, social benefits, climate, fuel prices, immigration, Islam, equal pay, LGB-rights, and several measures of social distance and group favouritism were not found to be statistically significant predictors in this analysis.

The adjusted R-squared for the model is 0.4062. Among the predictors, significant variables include level of education (Estimate = -2.2044, p-value = 0.00763), attitudes towards social benefits (Estimate = -1.9359, p-value = 0.03729), Islam (Estimate = -3.2628, p-value = 0.00124), perceived social distance towards FSU individuals (Estimate = 2.2490, p-value = 0.00566), and in-group favouritism towards Muslims (Estimate = 2.1648, p-value = 0.04216). However, other variables such as taxing the rich, climate, immigration, equal pay, LGB-rights, perceived social distance towards Turkish, German, Christian, and non-religious individuals, Belonging, attachment, and self-identified ethnic group were not found to be statistically significant predictors in this analysis. In addition to the significant variables mentioned earlier, some predictors came close to meeting the threshold for significance. These include attitudes towards fuel prices (Estimate = 1.4701, p-value = 0.08188), equal pay (Estimate = 1.3387, p-value = 0.06756), and German in-group favouritism (Estimate = 2.6970, p-value = 0.06304).

The adjusted R-squared for the model is 0.1914. Among the predictors, significant variables include attitudes towards taxing the rich (Estimate = -0.6797338, p-value = 0.038547), immigration (Estimate = -1.1692163, p-value = 0.003246), and Islam (Estimate = -1.3668919, p-value = 0.000557). The more positive at Dutch Muslim is about taxing the rich, immigration and Islam, the less likely a Dutch Muslim is to vote for PVV. The more distant one feels from Dutch Moroccans, the more likely one is to vote for the PVV (Estimate = 0.7867001, p-value = 0.051232). These results suggest that perceptions of immigration, attitudes towards Islam, and social distance from Moroccans significantly influence the likelihood of Dutch Muslims voting for PVV. However, other variables such as education, social benefits, climate, fuel prices, equal pay, LGB-rights, perceived social distance towards Surinamese, Turkish, Dutch, Muslim, Christian, and non-religious individuals, feeling accepted as belonging in the Netherlands, attachment to the Netherlands, self-identified ethnic group, and favouritism towards Dutch and Muslim in-groups were not found to be statistically significant predictors in this analysis.

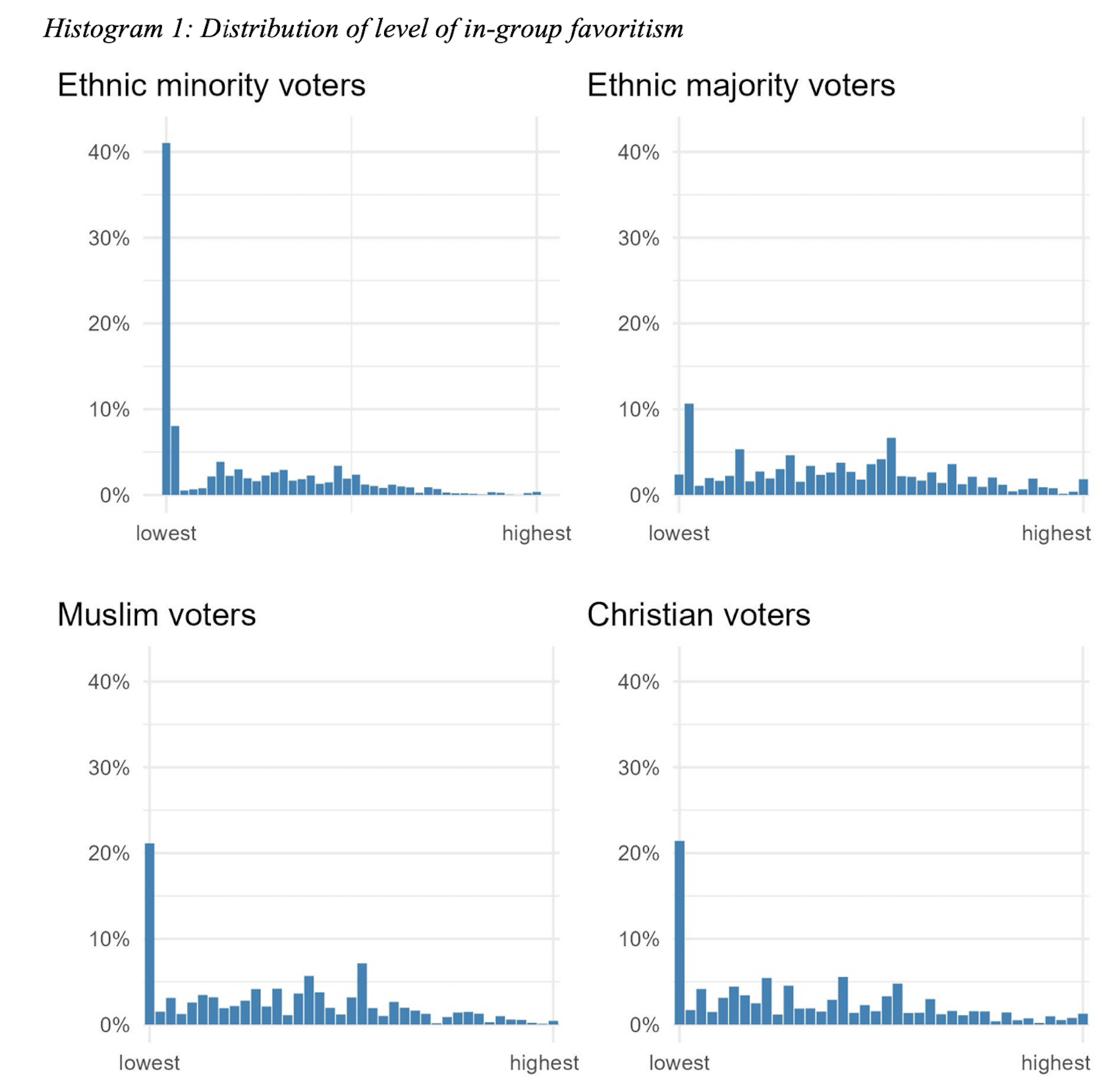

In-group Favouritism

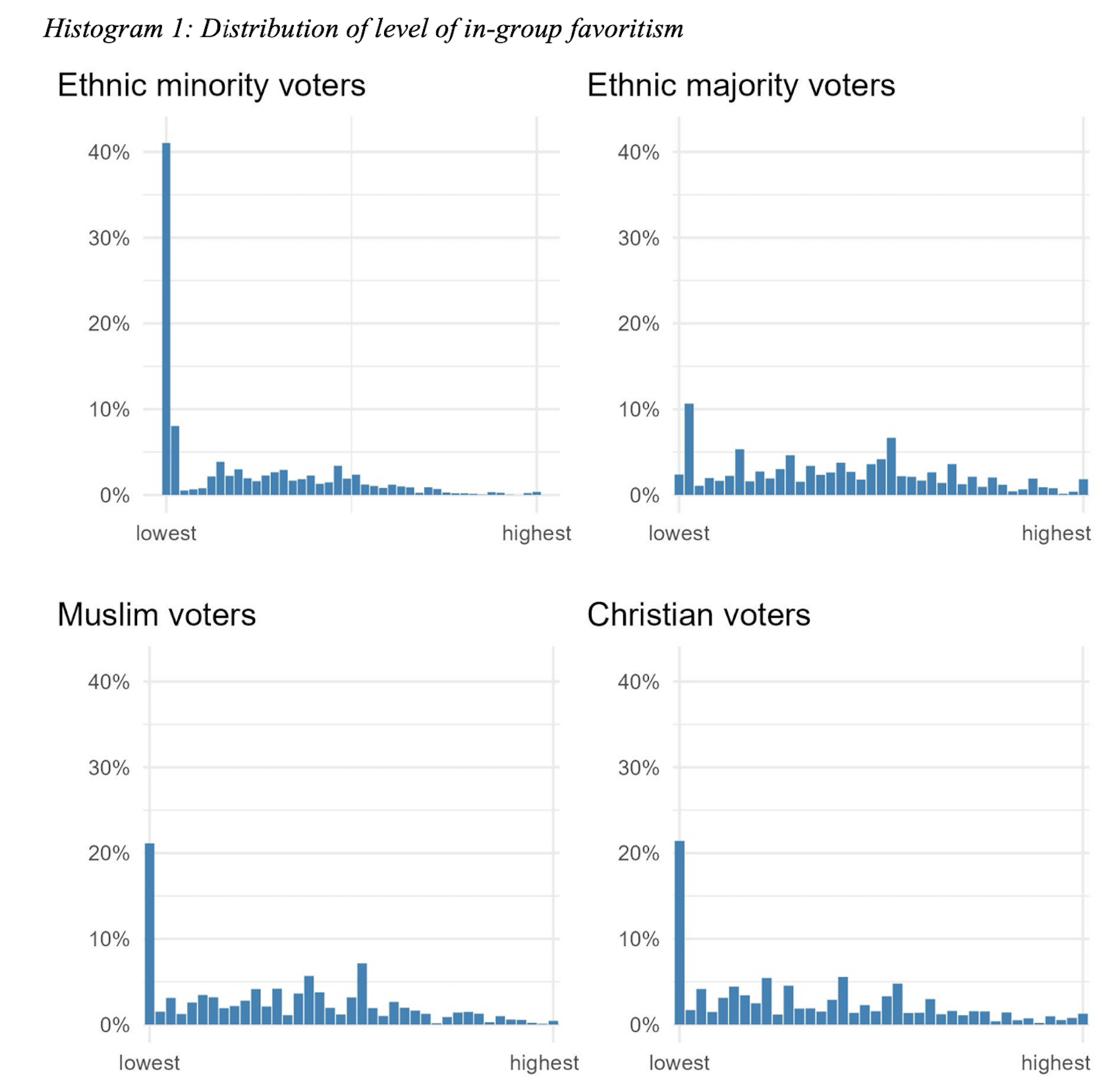

The analysis of in-group favouritism amongst ethnic minority and majority groups, as well as Muslims and Christians in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, reveals differences in in-group favouritism scores. Amongst the majority ethnic group voters, in-group favouritism emerges as notably higher compared to minority ethnic groups. Muslim and Christian in-group favouritism are comparable.

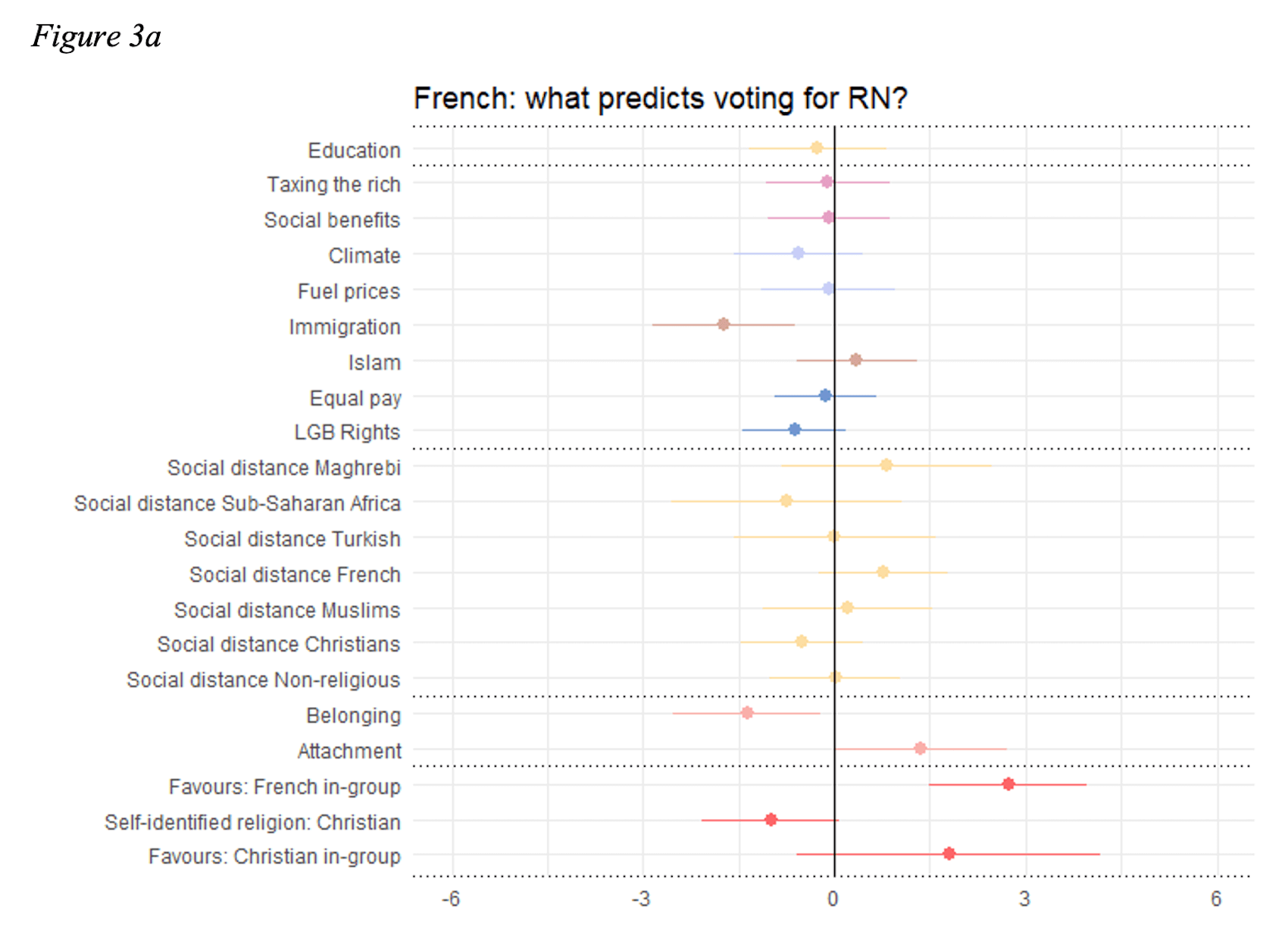

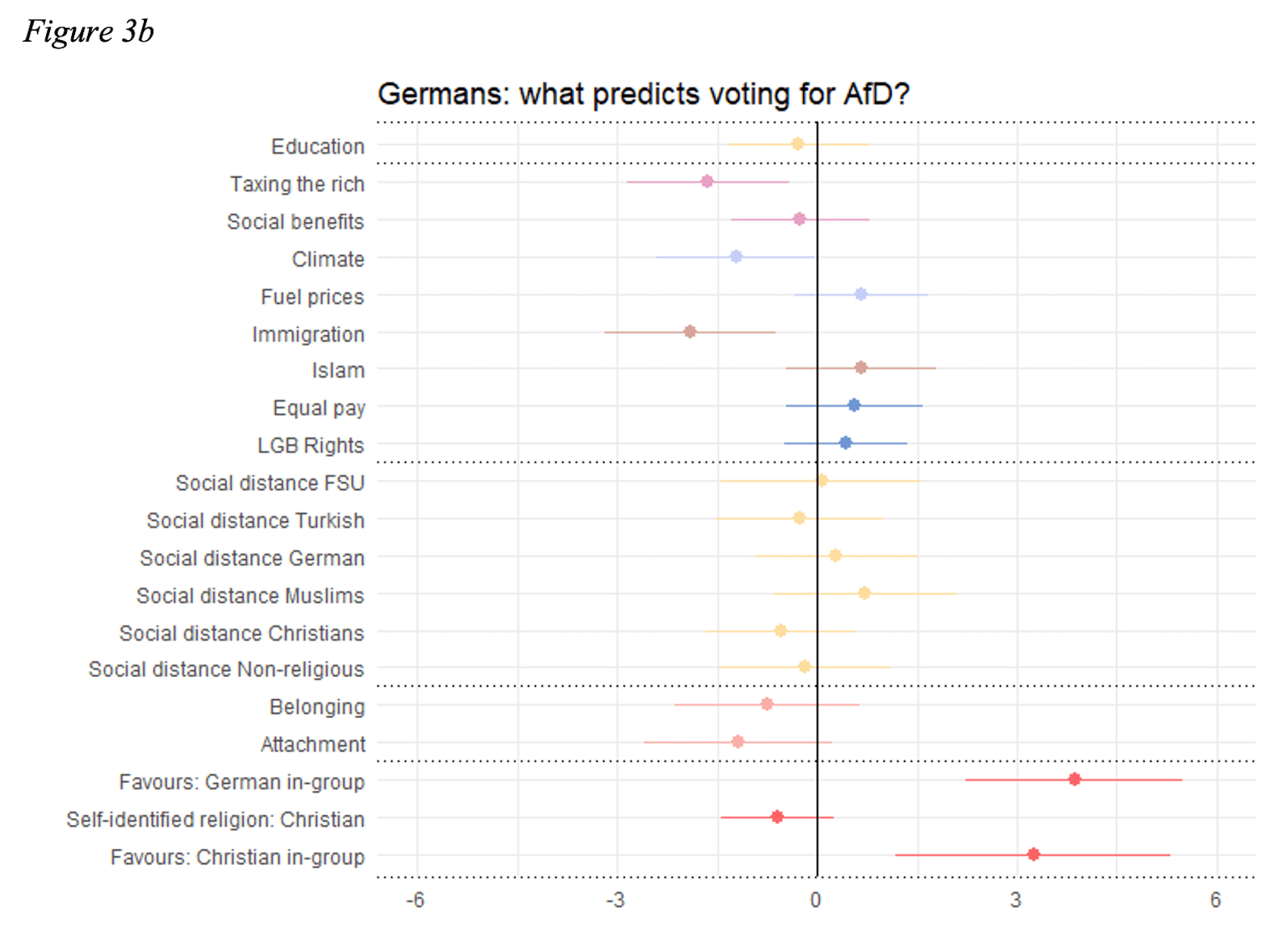

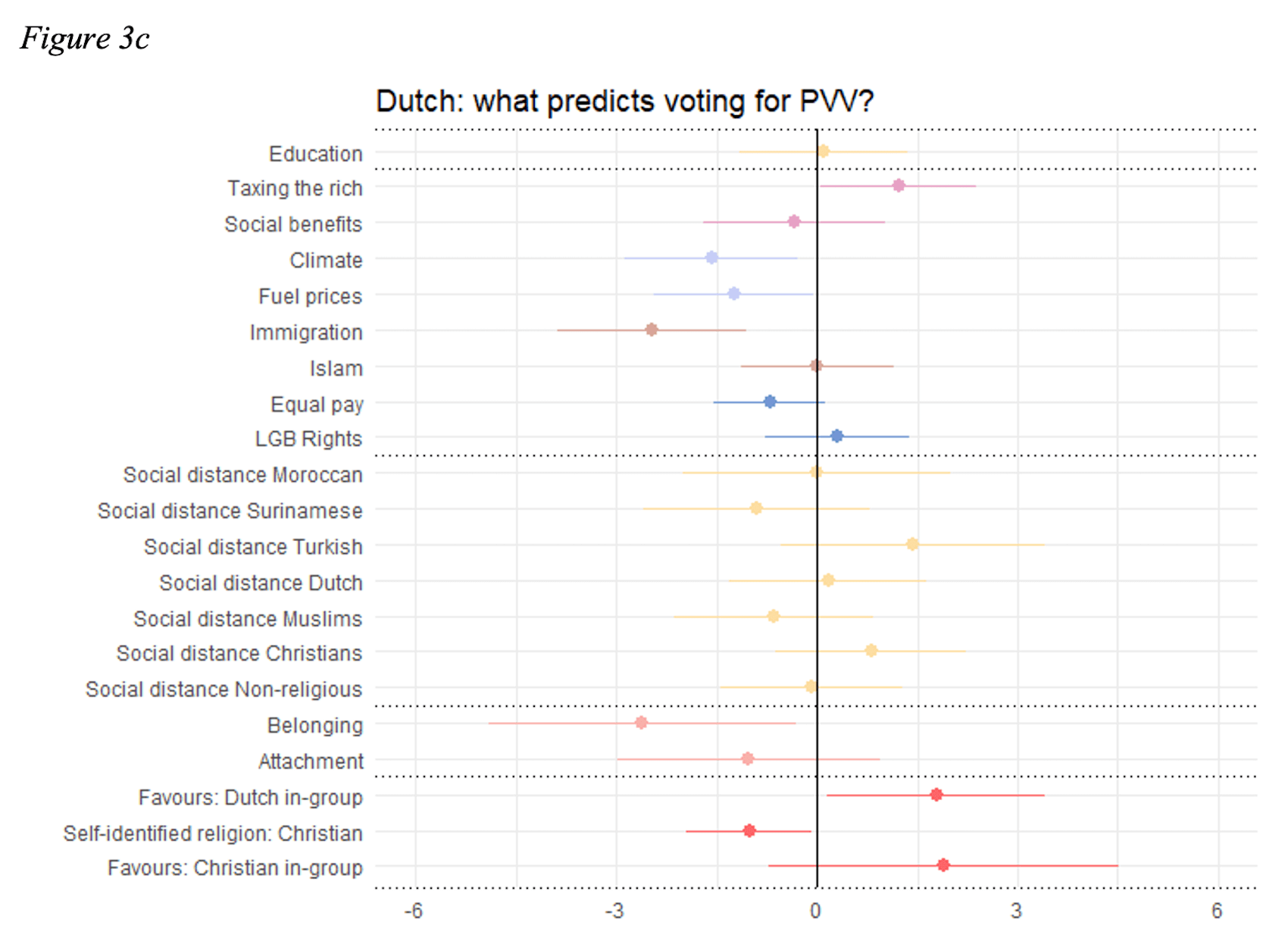

In-group Favouritism as a Stronger Predictor to Voting for PRRPs

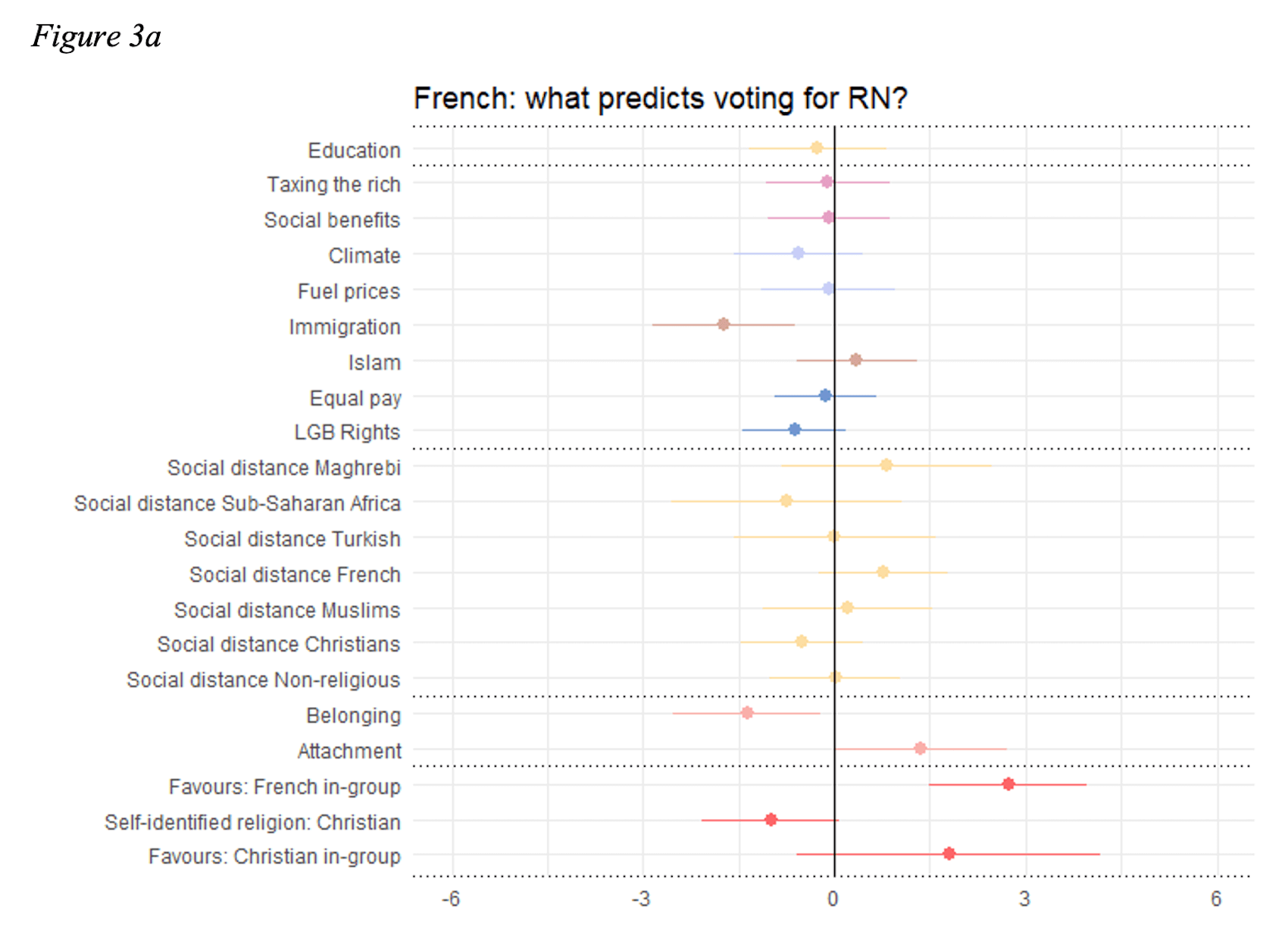

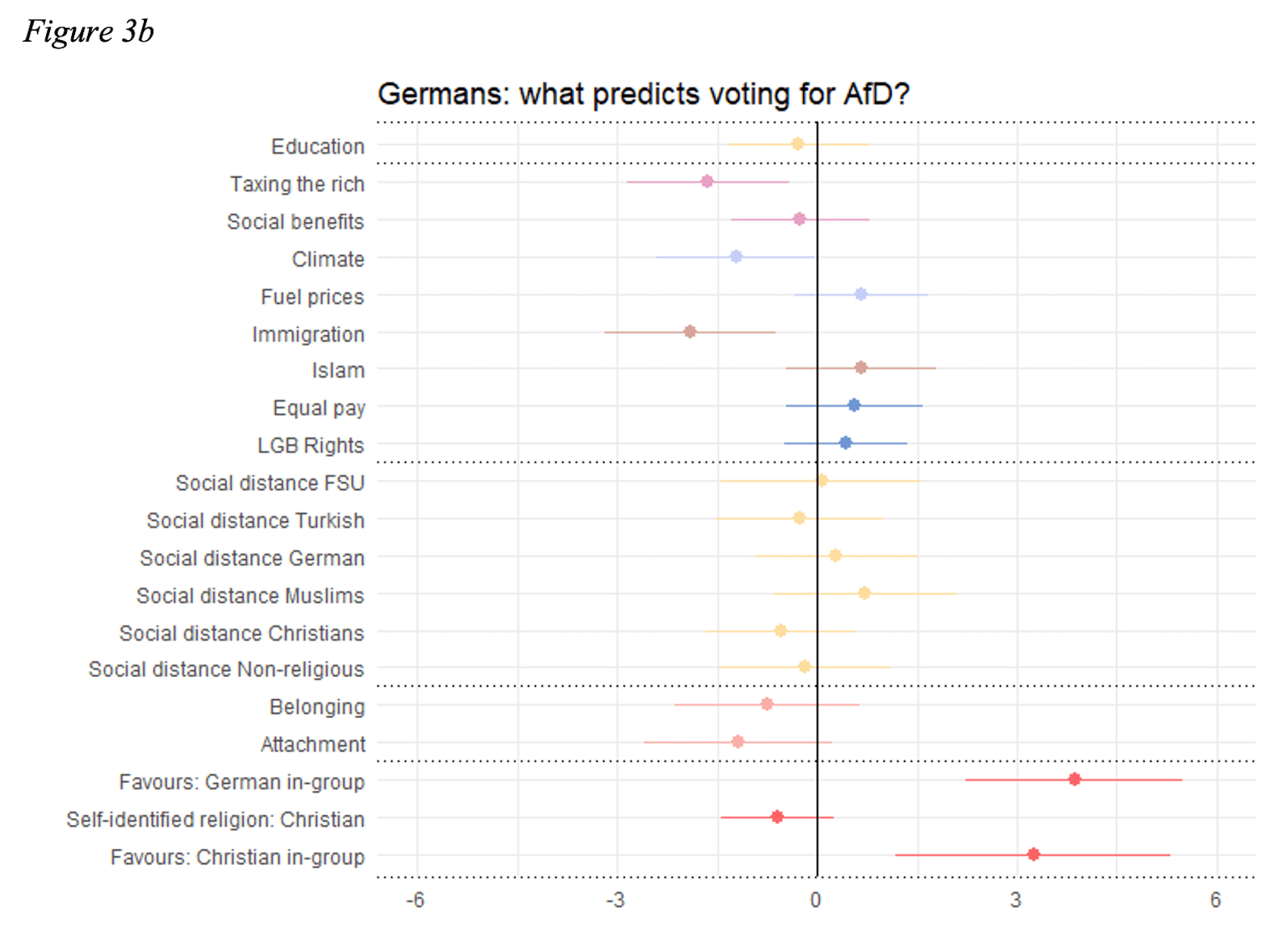

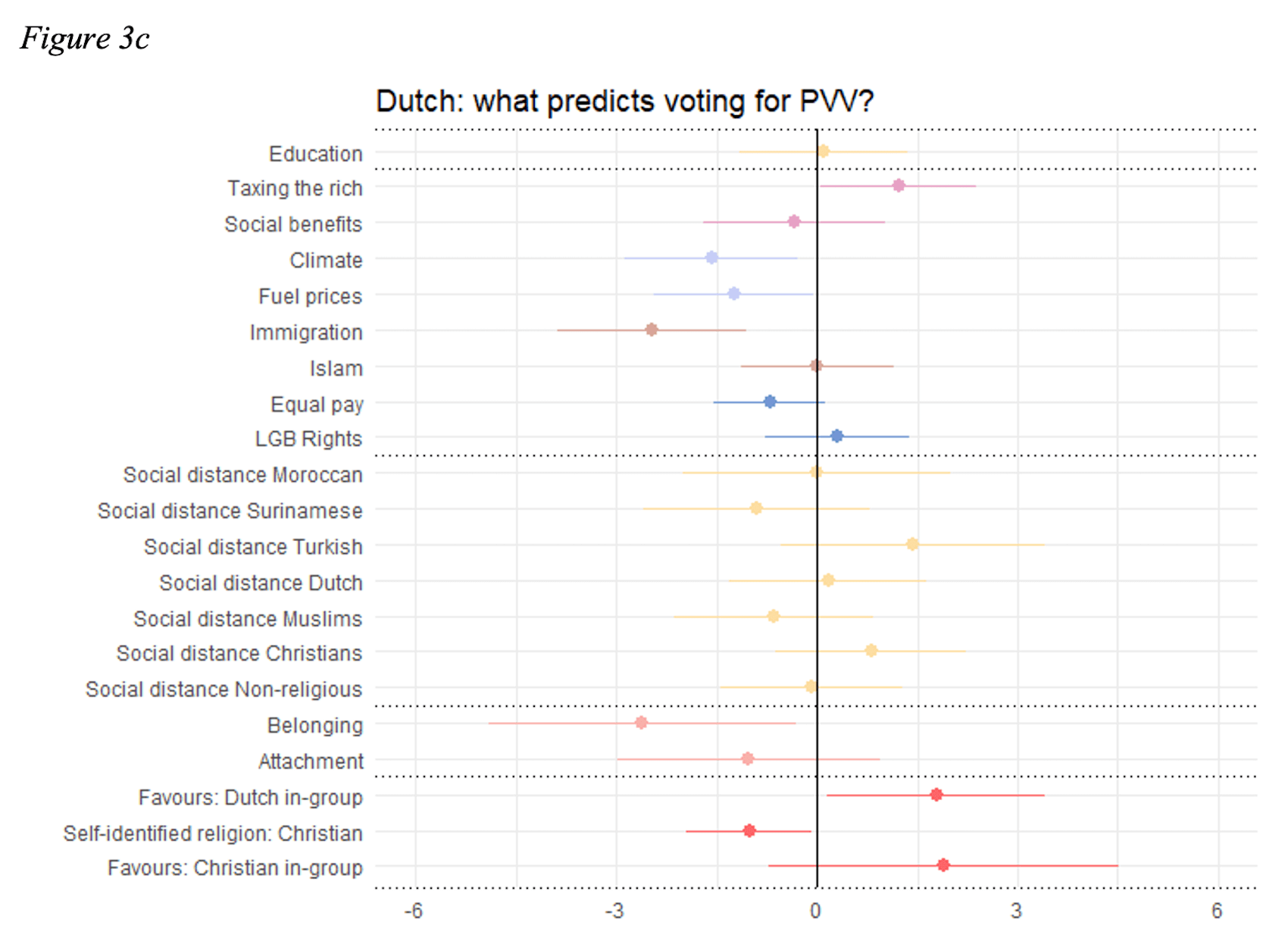

The findings across Figures 3a, 3b, and 3c underscore the significance of measuring in-group favouritism when examining voting behaviour for PRRPs. In each case, a substantial portion of the variance in the likelihood to vote for these parties is accounted for by factors related to in-group favouritism and attachment. Notably, French and German in-group favouritism emerge as the strongest predictors of voting behaviour for RN and AfD, respectively, outweighing other variables such as immigration attitudes. In the Netherlands, feeling accepted as belonging in the Netherlands was the strongest indicator of voting PVV, with those who feel less accepted being more likely to vote PVV. While negative attitudes towards immigration remain a potent predictor across all cases, views that pertain to the in-group predict PRRP voting more strongly.

The adjusted R-squared for the model predicting whether French voters without a migration background vote for RN is 0.1626, indicating that approximately 16.26% of the variance in likelihood to vote for RN is accounted for by the predictor variables. Among the predictor variables, statistically significant predictors include attitudes towards immigration (estimate = -1.727, p < 0.01), feeling accepted as belonging in France (estimate = -1.363, p < 0.05), French in-group favouritism (estimate = 2.731, p < 0.001), and feelings of attachment to France (estimate = 1.360, p < 0.05). These results suggest that negative attitudes towards immigration and a strong sense of French identity are associated with a higher likelihood of voting for RN, while positive attitudes towards France and attachment to the country are associated with a lower likelihood of voting for RN. Conversely, variables such as education, taxing the rich, social benefits, and others are not statistically significant predictors of voting for RN in this model. The indicator with the highest impact was French in-group favouritism. Having a stronger preference for the French in-group is associated with a substantially higher likelihood of voting for RN.

The adjusted R-squared for the model predicting whether German voters without a migration background vote for AfD is 0.2739, indicating that approximately 27.39% of the variance in likelihood to vote for AfD is accounted for by the predictor variables. Among the predictor variables, statistically significant predictors include attitudes towards immigration (estimate = -1.905, p < 0.01), feelings of acceptance as belonging in Germany (estimate = -0.744, p < 0.05), German in-group favouritism (estimate = 3.862, p < 0.001), and Christian in-group favouritism (estimate = 3.25373, p < 0.001). These results suggest that negative attitudes towards immigration and a strong sense of German and Christian identity are associated with a higher likelihood of voting for AfD, while positive attitudes towards Germany and attachment to the country are associated with a lower likelihood of voting for AfD. Conversely, variables such as education, taxing the rich, social benefits, and others are not statistically significant predictors of voting for AfD in this model. The indicator with the highest impact was German in-group favouritism. Having a stronger preference for the German in-group is associated with a substantially higher likelihood of voting for AfD, amongst Germans without a migration background.

The adjusted R-squared for the model predicting whether Dutch voters without a migration background vote for PVV is 0.2732, indicating that approximately 27.32% of the variance in likelihood to vote for PVV is accounted for by the predictor variables. Among the predictor variables, statistically significant predictors include attitudes towards immigration (estimate = -2.463, p < 0.001), concern about climate change (estimate = -1.579, p < 0.05), raising fuel prices (estimate = -1.246, p < 0.05), feelings of acceptance as belonging in the Netherlands (estimate = -2.616, p < 0.05), and preference for the Dutch in-group (estimate = 1.784, p < 0.05). These results suggest that negative attitudes towards immigration are associated with a higher likelihood of voting for PVV, while positive attitudes towards the Netherlands and attachment to the country are associated with a lower likelihood of voting for PVV. Conversely, variables such as education, taxing the rich, social benefits, and others are not statistically significant predictors of voting for PVV in this model. The indicator with the highest impact was feeling accepted as belonging in the Netherlands. Feeling less accepted is associated with a substantially higher likelihood of voting for PVV.

Conclusion

This paper has focused on the likelihood of minorities and majorities to vote for PRRPs and what explains the voting likelihoods. In France and Germany, there are remarkably few differences in the likelihood of voting for minority and majority groups. In France, voters with a Turkish background exhibit the highest inclination to support RN, followed closely by Christian and non-migrant French voters. Conversely, Muslims show the lowest likelihood of supporting RN. In Germany, voters from the Former Soviet Union are most likely to support AfD, with no significant difference in Muslim voters’ likelihood to support AfD compared to other groups. In the Netherlands, Dutch voters without a migration background are significantly more inclined to vote for PVV, while Muslim, Turkish, and Moroccan voters are significantly less likely to support PVV compared to other groups, with Muslims showing the lowest likelihood.

I also discuss the factors influencing the voting behaviour of Muslims in France, Germany, and the Netherlands regarding PRRPs. Generally speaking, issues are the biggest predictor of Muslim voting for PRRPs. In France, attitudes towards fuel prices, social distance towards Maghrebi individuals, and attachment to France significantly impact voting for RN. In Germany, level of education, attitudes towards social benefits, Islam, perceived social distance towards FSU individuals, and in-group favouritism towards Muslims are significant predictors of AfD support. In the Netherlands, attitudes towards taxing the rich, immigration, and Islam, along with social distance from Dutch Moroccans, influence the likelihood of voting for PVV among Dutch Muslims.

Moreover, when it comes to majority voters, I find in-group favouritism predicts voting more than issues do. French and German in-group favouritism emerge as the strongest predictors of voting behaviour for RN and AfD, respectively, outweighing other variables such as immigration attitudes. In the Netherlands, feeling accepted as belonging in the country was the strongest indicator of voting PVV, with those who feel less accepted being more likely to vote PVV. Overall, negative attitudes towards immigration remain a potent predictor across all cases, while views related to the in-group predict PRRP voting more strongly.

Lastly, the examination of in-group favouritism among ethnic minority and majority groups, alongside Muslims and Christians in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, reveals that in-group favouritism is much higher among racial and ethnic majority voters. Meanwhile, the analysis shows remarkably low levels of in-group favouritism within minority groups. This trend underscores that groups with more power and privilege tend to uphold and reinforce their social dominance through favouring their own group, while the groups with less power and privilege do not favour their in-group to the same extent and might benefit more from siding with the dominant out-group.

I argue that in-group favouritism can be extended towards voting for PRRPs because the analysis reveals that French, German and Dutch in-group favouritism and PRRP voting are strongly related for racial and ethnic majority groups in France, Germany and the Netherlands. The relationship between majority group in-group favouritism and PRRP voting is stronger for majority voters compared to minority voters due to the dynamics of social identity and power asymmetry. For majority voters, who typically hold higher social status and enjoy dominant societal norms, in-group favouritism serves as a reinforcing mechanism of their perceived superiority and control over resources. In-group favouritism not only bolsters their positive self-image but also reinforces their position of privilege within the social hierarchy. I argue this extends to PRRP voting. Moreover, for majority voters, in-group favouritism and PRRP voting is intricately linked with the preservation of their cultural and political hegemony. Supporting policies or political parties aligned with their group interests not only reinforces their social identity but also serves to protect and advance their collective interests within society. In-group favouritism as well as voting for PRRPs becomes a means of maintaining the status quo and resisting challenges to their dominance from minority groups.

In contrast, minority voters often face systemic barriers and discrimination that limit their access to resources and opportunities. Sometimes their situation leads to in-group favouritism, but in some situations it is more beneficial to favour the dominant out-group. This is most visible in France and Germany, where racial and ethnic minority and Muslim voters are just as likely to vote for PRRPs as their majority counterparts. In France, the Turkish group of voters is even most likely to vote for PRRPS, possibly because they are only a very small part of the population and do not have a very large in-group community to favour, unlike in Germany and the Netherlands where there are larger Turkish communities. Thus, siding with the out-group through PRRP voting might reveal an inclination towards favouring the dominant out-group to navigate existing power structures. In the Netherlands, the strong focus on multiculturalism historically, might have bolstered the Muslim, Turkish and Moroccan communities leading them to be much less likely than other groups to vote for PRRPs. However, this could also be due to the relatively explicit nature of the PVV in their opposition against Muslims, especially those of Turkish and Moroccan descent.

In conclusion, the significance of in-group favouritism varies between majority and minority voters due to the differential distribution of power and privilege within society. For majority voters, in-group favouritism reinforces their social dominance and cultural hegemony, whereas for minority voters, it may be one of many strategies employed in the pursuit of equality and social change. In-group favouritism is also more important compared to immigration attitudes in predicting PRRP voting. While negative attitudes towards immigration remain a significant predictor across most cases, I show that in-group favouritism often outweighs immigration sentiments, especially among majority voters. This suggests that for majority groups, the allegiance to their in-group holds greater sway in shaping their electoral choices than attitudes towards immigration, arguably the out-group.

Conversely, among minority voters, policy positions, especially regarding issues relevant to their community, such as immigration policies, play a slightly more decisive role in guiding their voting behaviour. This relationship between in-group favouritism, immigration attitudes, and policy preferences underscores how important it is to consider in-group favouritism in future research, recognizing its relationship with power dynamics. By doing so, we can deepen our understanding of the factors shaping electoral behaviour and contribute to a more inclusive and equitable democratic process.

References

Abou-Chadi T and Helbling M (2018) How Immigration Reforms Affect Voting Behavior. Political Studies 66(3): 687–717.DOI: 10.1177/0032321717725485.

Abou-Chadi T and Wagner M (2019) The Electoral Appeal of Party Strategies in Postindustrial Societies: When Can the Mainstream Left Succeed? The Journal of Politics 81(4): 1405–1419. DOI: 10.1086/704436.

Albertazzi D and Mcdonnell D (2008) Twenty-First Century Populism (eds D Albertazzi and D McDonnell). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. DOI: 10.1057/9780230592100.

Althof A (2018) Right-wing populism and religion in Germany: Conservative Christians and the Alternative for Germany (AfD). Zeitschrift für Religion, Gesellschaft und Politik: 335–363. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41682-018-0027-9.

American National Election Studies (2021). ANES 2020 Time Series Study Full Release [dataset and documentation]. February 10, 2022 version. https://electionstudies.org/data-center/2020-time-series-study/ Accessed December 17 2024

Awan I (2014) Islamophobia and twitter: A typology of online hate against muslims on social media. Policy and Internet 6(2): 133–150. DOI: 10.1002/1944-2866.POI364.

Ayoub PM (2019) Intersectional and Transnational Coalitions during Times of Crisis: The European LGBTI Movement. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 26(1): 1–29. DOI: 10.1093/sp/jxy007.

Bergh J and Bjørklund T (2011) The Revival of Group Voting: Explaining the Voting Preferences of Immigrants in Norway. Political Studies 59(2): 308–327. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00863.x.

Baysu G and Swyngedouw M (2020) What Determines Voting Behaviors of Muslim Minorities in Europe: Muslim Identity or Left‐Right Ideology? Political Psychology 41(5): 837–860. DOI: 10.1111/pops.12653.

Bizumic B, Duckitt J, Popadic D, et al. (2009) A cross-cultural investigation into a reconceptualization of ethnocentrism. European Journal of Social Psychology 39(6): 871–899. DOI: 10.1002/ejsp.589.

Bird K, Saalfeld T and Wüst AM (2010) Ethnic diversity, political participation and representation: A theoretical framework. In: The Political Representation of Immigrants and Minorities, Voters, Parties and Parliaments in Liberal Democracies. Routledge, pp. 1–22. DOI: 10.4324/9780203843604.

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00126

Bracke S and Hernández Aguilar LM (2020) “They love death as we love life”: The “Muslim Question” and the biopolitics of replacement. The British Journal of Sociology (January): 680–701. DOI: 10.1111/1468-4446.12742.

Brubaker R (2017) Between nationalism and civilizationism: the European populist moment in comparative perspective. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40(8). Taylor & Francis: 1191–1226. DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1294700.

Coppock A and McClellan OA (2018) Validating the Demographic, Political, Psychological, and Experimental Results Obtained from a New Source of Online Survey Respondents. Working Paper. DOI: 10.1177/2053168018822174.

Cremaschi, S., Rettl, P., Cappelluti, M., & De Vries, C. E. (2024). Geographies of discontent: Public service deprivation and the rise of the far right in Italy. American Journal of Political Science, first published. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12936

Creighton, M. (2023). Hidden hate: The resilience of xenophobia. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/crei12345 Dancygier RM (2017) Dilemmas of Inclusion. Princeton University Press. DOI: 10.2307/j.ctt1vwmgf2.

de Haas, H. (2023). How migration really works: A factful guide to the most divisive issue in politics. Viking.

European Parliament. (2018, May 24). New EU data protection rules take effect on Friday. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20180522IPR04042/new-eu-data-protection-rules-take-effect-on-friday Accessed December 17 2024

Farris SR (2017) In the Name of Women’s Rights, The Rise of Femonationalism. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Fernández-Reino M, Di Stasio V and Veit S (2023) Discrimination unveiled: a field experiment on the barriers faced by Muslim women in Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain. European Sociological Review 39(3): 479–497. DOI: 10.1093/esr/jcac032.

Fernández-Reino, M., Brindle, B. & Vargas-Silva, C. (2024) Migrants and Housing in the UK. Migration Observatory briefing, COMPAS, University of Oxford. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migrants-and-housing-in-the-uk/ Accessed December 17 2024

Font J and Méndez M (2013) Surveying Ethnic Minorities and Immigrant Populations. Amsterdam: IMISCOE Research Amsterdam University Press. Available at: https://www.imiscoe.org/docman-books/354-font-a-mendez-eds-2013 Accessed August 16 2023.

FRA: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2017) Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey (EU-MIDIS II): Main Results. DOI: 10.2811/902610.

Frey A (2020) ‘Cologne changed everything’ – The effect of threatening events on the frequency and distribution of intergroup conflict in Germany. European Sociological Review 36(5): 684–699. DOI: 10.1093/esr/jcaa007.

Geurts, N., Glas, S., & Spierings, N. (2023). “It is for God to judge”1: Understanding Why and When Islamic Religiosity Inhibits Homotolerance. Journal of Homosexuality, 71(13), 2901–2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2023.2267723

Ghekiere, A., & Verhaeghe, P.-P. (2022). How does ethnic discrimination on the housing market differ across neighborhoods and real estate agencies? Journal of Housing Economics, 55, 101820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2021.101820

Grewal S and Hamid S (2022) Discrimination, Inclusion, and Anti‐System Attitudes among Muslims in Germany. American Journal of Political Science 0(0): 1–18. DOI: 10.1111/ajps.12735.

Heath A and Richards L (2019) How do Europeans differ in their attitudes to immigration? Findings from the European Social Survey 2002/03 -2016/17. the 3rd International ESS Conference. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/1815199X.

Helbling M and Traunmüller R (2018) What Is Islamophobia? Disentangling Citizens’ Feelings Towards Ethnicity, Religion and Religiosity Using a Survey Experiment. British Journal of Political Science: 1–18. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000054.

Jardina A and Stephens-Dougan L (2021) The electoral consequences of anti-Muslim prejudice. Electoral Studies 72(June): 102364. DOI: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102364.

Judis, J. B., & Teixeira, R. (2002). The emerging democratic majority. Simon & Schuster.

Judis, J. B., & Teixeira, R. (2023). Where have all the Democrats gone?: The soul of the party in the age of extremes(illustrated ed.). Henry Holt and Company.

Khalimzoda, I., Sadaf, S., & van Oosten, S. (2025). Journalistic Tactic and Intercultural Deficit: Post–publication Audience Engagement in a Finnish News Case Study. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/c68q2

Kuru AT (2008) Secularism, state policies, and muslims in Europe analyzing French exceptionalism. Comparative Politics41(1): 1–19. DOI: 10.5129/001041508×12911362383552.

Koopmans, R. (2013, June 25-27). Religious fundamentalism and out-group hostility among Muslims and Christians in Western Europe. Presentation at the 20th International Conference of Europeanists, Amsterdam. Social Science Center Berlin (WZB). https://www.wzb.eu/system/files/docs/sv/iuk/ruud_koopmans_religious_fundamentalism_and_out-group_hostility_among_muslims_and_christian.pdf Accessed December 17 2024

Korteweg AC and Yurdakul G (2021) Liberal feminism and postcolonial difference: Debating headscarves in France, the Netherlands, and Germany. Social Compass 68(3): 410–429. DOI: 10.1177/0037768620974268.

Kortmann M, Stecker C and Weiß T (2019) Filling a Representation Gap? How Populist and Mainstream Parties Address Muslim Immigration and the Role of Islam. Representation 55(4). Taylor & Francis: 435–456. DOI: 10.1080/00344893.2019.1667419.

Krupnikov Y and Levine AS (2014) Cross-Sample Comparisons and External Validity. Journal of Experimental Political Science 1(1): 59–80. DOI: 10.1017/xps.2014.7.

Lee T (2008) Race, immigration, and the identity-to-politics link. Annual Review of Political Science 11(1): 457–478. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.051707.122615.

Leeper TJ, Hobolt SB and Tilley J (2020) Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments. Political Analysis 28(2): 207–221. DOI: 10.1017/pan.2019.30.

Lim, M., van Oosten, S., & Wan Jaafar, W. M. (2024). Type of primary school attended influences bribe-giving intentions. Public Integrity, 26(3), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2024.2353710

Loukili S (2021a) Fighting Fire with Fire? “Muslim” Political Parties in the Netherlands Countering Right-Wing Populism in the City of Rotterdam. Journal of Muslims in Europe (April). DOI: 10.1163/22117954-12341409.

Loukili S (2021b) Making Space , Claiming Place Social Media and the Emergence of the “Muslim” Political Parties DENK and NIDA in the Netherlands. Journal for Religion, Film and Media 7(2): 107–131. DOI: 10.25364/05.7.

Mansouri F and Vergani M (2018) Intercultural contact, knowledge of Islam, and prejudice against muslims in Australia. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 66(June): 85–94. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.07.001.

Marzouki N, McDonell D and Roy O (2016) Saving the People: How Populists Hijack Religion. London: Hurst & Company.

McGlynn R (2020) They Hate Our Freedoms: Homosexuality and Islam in the Tolerant West. In: Contestations of Liberal Order. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 151–174. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-22059-4_6.

Mepschen P, Duyvendak JW and Tonkens EH (2010) Sexual Politics, Orientalism and Multicultural Citizenship in the Netherlands. Sociology 44(5). SAGE PublicationsSage UK: London, England: 962–979. DOI: 10.1177/0038038510375740.

Mullinix KJ, Leeper TJ, Druckman JN, et al. (2015) The Generalizability of Survey Experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science 2(2): 109–138. DOI: 10.1017/XPS.2015.19.

Nadler, A., Hepplewhite, M., & van Oosten, S. (2025). Does In-Group Favouritism Lead to In-Group Voting? An Experimental Study of Vote Choice among Minority and Majority Voters. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/7fze4

Nandi A and Platt L (2020) The relationship between political and ethnic identity among UK ethnic minority and majority populations. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46(5): 957–979. DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1539286.

Puar J (2013) Rethinking homonationalism. International Journal of Middle East Studies 45(2): 336–339. DOI: 10.1017/S002074381300007X.

Phalet K, Baysu G and Verkuyten M (2010) Political Mobilization of Dutch Muslims: Religious Identity Salience, Goal Framing, and Normative Constraints. Journal of Social Issues 66(4): 759–779. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01674.x.

Rahbari L (2021) When gender turns right: racializing Islam and femonationalism in online political discourses in Belgium. Contemporary Politics 27(1). Taylor & Francis: 41–57. DOI: 10.1080/13569775.2020.1813950.

Rovny, J (2019). Ethnic minorities, political competition, and democracy: Circumstantial liberals. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/9780198906742.001.0001

Saral M (2020) State, Religion and Muslims (eds M Saral and Ş Onur Bahçecik). BRILL. DOI: 10.1163/9789004421516.

Schmuck D and Matthes J (2019) Voting “Against Islamization”? How Anti-Islamic Right-Wing, Populist Political Campaign Ads Influence Explicit and Implicit Attitudes Toward Muslims as Well as Voting Preferences. Political Psychology 40(4): 739–757. DOI: 10.1111/pops.12557.

Schotel, A. L. (2021). A Rainbow Bundestag? An Intersectional Analysis of LGBTI Representation in Angela Merkel’s Germany. German Politics, 31(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.1991325

Skocpol, T. (2020). The elite and popular roots of contemporary Republican extremism. In T. Skocpol & C. Tervo (Eds.), Upending American politics: Polarizing parties, ideological elites, and citizen activists from the Tea Party to the anti-Trump resistance (pp. 3–28). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190083526.003.0001

Skocpol, T., & Tervo, C. (Eds.). (2020). Upending American politics: Polarizing parties, ideological elites, and citizen activists from the Tea Party to the anti-Trump resistance. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190083526.001.0001

Skocpol, T., & Williamson, V. (2011). The Tea Party and the remaking of Republican conservatism. Oxford University Press.

Sobolewska M (2006) Ethnic Agenda: Relevance of Political Attitudes to Party Choice. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 15(2): 197–214. DOI: 10.1080/13689880500178781.

Sobolewska, M., & Ford, R. (2020). Brexitland. Cambridge University Press.

Snipes A and Mudde C (2020) France’s (Kinder, Gentler) Extremist: Marine le Pen, Intersectionality, and Media Framing of Female Populist Radical Right Leaders. Politics and Gender 16(2): 438–470. DOI: 10.1017/S1743923X19000370.

Glas S and Spierings N (2022) The impact of anti-Muslim hostilities on how Muslims connect their religiosity to support for gender equality in Western Europe. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:909578. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.909578

Tajfel H and Turner JC (1979) An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In: W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (ed.) The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole.

Tesler M (2013) The return of old-fashioned racism to white Americans’ partisan preferences in the Early Obama Era. Journal of Politics 75(1): 110–123. DOI: 10.1017/S0022381612000904.

Thom, Elizabeth, and Theda Skocpol, ‘Trump’s Trump: Lou Barletta and the Limits of Anti-Immigrant Politics in Pennsylvania’, in Theda Skocpol, and Caroline Tervo (eds), Upending American Politics: Polarizing Parties, Ideological Elites, and Citizen Activists from the Tea Party to the Anti-Trump Resistance (New York, 2020; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 Jan. 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190083526.003.0006, accessed 17 Dec. 2024.

Tiberj V and Michon L (2013) Two-tier Pluralism in ‘ Colour-blind ’ France Two-tier Pluralism in ‘ Colour-blind ’. 2382. DOI: 10.1080/01402382.2013.773725.

van der Brug W and van Spanje J (2009) Immigration, Europe and the ‘new’ cultural dimension. European Journal of Political Research 48(3): 309–334. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.00841.x.

van Es MA (2019) Muslim women as ‘ambassadors’ of Islam: breaking stereotypes in everyday life. Identities 26(4). Routledge: 375–392. DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2017.1346985.

van Oosten S (2020) An MP Who Looks Like Me? Pre-registration. OSF. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/JTDQW

van Oosten S (2022a) What shapes voter expectations of Muslim politicians’ views on homosexuality: stereotyping or projection? Electoral Studies 80(December). Elsevier Ltd: 1–11. DOI: 10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102553.

van Oosten, S. (2022b). Stereotyperen kiezers Islamitische politici als homofoob? Stuk Rood Vlees, 2022(12).https://stukroodvlees.nl/stereotyperen-kiezers-islamitische-politici-als-homofoob/ Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten, S. (2023a). Which voters stereotype Muslim politicians as homophobic? ECPR The Loop 2023(2). https://theloop.ecpr.eu/which-voters-stereotype-muslim-politicians-as-homophobic/ Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten, S. (2023b). Why did the Netherlands vote PVV? COMPAS Blog, 2023(12). https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/2023/why-did-the-netherlands-vote-for-wilders-pvv-implications-for-migration-policy/ Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten S, Mügge L and Van der Pas D (2024a) Race/Ethnicity in Candidate Experiments: a Meta-Analysis and the Case for Shared Identification. Acta Politica 58(1). Palgrave Macmillan UK. DOI: 10.1057/s41269-022-00279-y.

van Oosten S (2024a) Waarom stemmen mensen PVV? Binnenlands Bestuur 2024(1). Binnenlands Bestuur B.V. https://www.binnenlandsbestuur.nl/carriere/verbeter-de-economische-positie-van-alle-nederlanders Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten S (2024b) Broadstancers hebben een electoraal voordeel. Binnenlands Bestuur 2024(2). Binnenlands Bestuur B.V. https://www.binnenlandsbestuur.nl/bestuur-en-organisatie/negatieve-vooroordeel-tegen-islamitische-politici-verdwijnt-helemaal-wanneer Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten S (2024c) Nationalists Pit Jewish and Muslim People Against Each Other and Why This Needs To Stop. COMPAS Blog, 2024(2). https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/article/a-battle-of-rhetoric-and-racism-how-nationalists-pit-jewish-and-muslim-people-against-each-other-and-why-this-needs-to-stop Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten S (2024d) ‘Judeonationalisme’ als nieuwe beschavingsretoriek. Binnenlands Bestuur 2024(3). Binnenlands Bestuur B.V. https://www.binnenlandsbestuur.nl/carriere/judeonationalisme-nadelig-voor-moslims-en-joden Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten S (2024e) Een wapen tegen moslims en links. Binnenlands Bestuur 2024(6). Binnenlands Bestuur B.V. https://www.binnenlandsbestuur.nl/carriere/judeonationalisme-speelt-kwetsbare-groepen-tegen-elkaar-uit Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten, S. (2024f). Judeonationalism: Calling out antisemitism to discredit Muslims. ECPR The Loop, 2024(6). https://theloop.ecpr.eu/judeonationalism-antisemitism-for-the-discrediting-of-muslims/ Accessed 17 December 2024.

van Oosten S, Mügge L, Hakhverdian A, Van der Pas D and Vermeulen F (2024b) French Ethnic Minority and Muslim Attitudes, Voting, Identity and Discrimination (EMMAVID) – EMMAVID Data France. Harvard Dataverse. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ULQEAY

van Oosten S, Mügge L, Hakhverdian A, Van der Pas D and Vermeulen F (2024c) German Ethnic Minority and Muslim Attitudes, Voting, Identity and Discrimination (EMMAVID) – EMMAVID Data Germany. Harvard Dataverse. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GT4N9J

van Oosten S, Mügge L, Hakhverdian A, Van der Pas D and Vermeulen F (2024d) Dutch Ethnic Minority and Muslim Attitudes, Voting, Identity and Discrimination (EMMAVID) – EMMAVID Data the Netherlands. Harvard Dataverse. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BGVJZQ