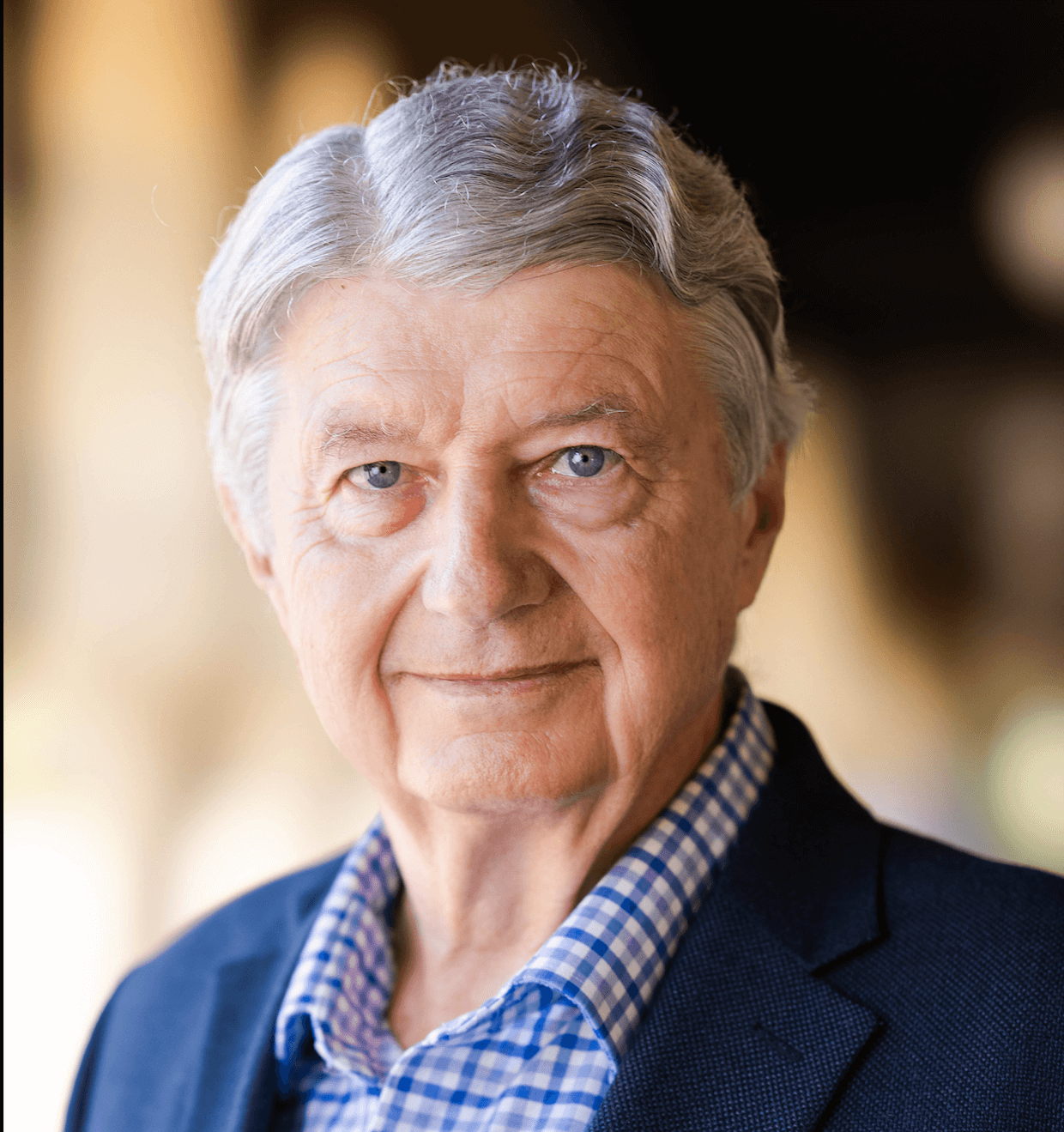

In an in-depth interview with the ECPS, Bruce E. Cain—Professor of Political Science at Stanford University—analyzes how Donald Trump has reshaped the Republican Party and advanced classical authoritarian strategies. “There’s no question that, whether by instinct or by deliberate strategy, Trump is playing the classical authoritarian game,” Professor Cain asserts. He situates Trumpism within long-term demographic, institutional, and ideological shifts while underscoring Trump’s unique use of crisis narratives, bullying tactics, and federal coercion. Professor Cain also warns that Trumpism has exploited structural weaknesses in party regulation, executive power, and campaign finance, stressing the urgency of reinforcing democratic guardrails to prevent lasting authoritarian consolidation.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In a wide-ranging and incisive interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Bruce E. Cain—Professor of Political Science at Stanford University and Director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West—offers a penetrating analysis of how Donald Trump’s leadership has reshaped the Republican Party and pushed American politics toward classical authoritarian strategies. “There’s no question that, whether by instinct or by deliberate strategy, Trump is playing the classical authoritarian game,” Professor Cain observes. “There’s no doubt that’s what he’s trying to do. It suits the way he has run his companies, and it suits the kinds of leaders he admires in other countries. He’s essentially following in their footsteps.”

Professor Cain situates Trumpism within broader structural transformations of American politics, emphasizing long-term demographic, geographic, and institutional shifts that made Trump’s rise possible. He points to “social sorting” and “party sorting” since the 1960s, along with growing racial diversity and economic inequality, as crucial background conditions. These shifts, he argues, preceded Trump and “made his rise possible,” even as his “adroit use of social media” and personal brand amplified their impact.

Central to Professor Cain’s analysis is Trump’s deliberate exploitation of crisis narratives and authoritarian tactics. Reflecting on Trump’s response to crises such as the Charlie Kirk assassination, Professor Cain notes that “Trump is playing the classical authoritarian game” and has escalated his reliance on bullying tactics compared to his first term. He highlights Trump’s willingness to deploy federal forces in Democratic-run cities, calling it “very disturbing and very unusual,” and likens it to the EU sending troops into member states to enforce policy—an action that violates deeply held American principles of state sovereignty.

Professor Cain also examines the evolving coalition underpinning the contemporary Republican Party. He underscores the critical role of the MAGA base, describing it as “maybe, at best, 40%, but more likely 30% of the Republican Party’s support,” driven in part by cultural grievance politics and white nationalist narratives. Yet, he stresses the uneasy alliance between this base and more traditional Republicans, warning of internal tensions that could shape future elections.

Institutionally, Professor Cain warns that Trumpism has both exploited and accelerated structural weaknesses in the American political system—from the weakening of party authority and campaign finance regulation to the expansion of executive power. He cautions that if the Supreme Court legitimizes Trump’s expansive claims of emergency powers and unilateral action, “it’ll be monkey see, monkey do,” with Democrats following suit—leading to instability and democratic erosion.

Professor Cain concludes by emphasizing the urgency of shoring up democratic guardrails, particularly regarding executive power, emergency provisions, and the role of the courts. His analysis offers a sobering reminder that while Trump may be unique, the authoritarian strategies he has deployed are embedded within deeper institutional vulnerabilities that will persist beyond his presidency.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Bruce Cain, revised for clarity and flow.

How Demography and Party Sorting Paved the Way for Trump

Professor Cain, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: Many scholars locate the transformation of the American Right within long-term structural changes dating back to the 1970s—such as realignments in race, region, and party organization—while others highlight the Trump and MAGA era as a moment of acute disruption. How do you conceptually distinguish between these deeper ideological and institutional evolutions and the more contingent, charismatic, and stylistic ruptures introduced by Trump?

Professor Bruce Cain: This is a really important point that you’re making. Because Trump sucks all the oxygen out of the conversation, people tend to think that everything has to do with Trump himself—his personality and his adroit use of social media. But it’s crucial to emphasize that there were larger demographic and political trends behind Trumpism.

Because the list is very long, I’ll focus on a couple that are particularly important. One is what we call social sorting. America is a very mobile society, and because of this mobility, many states—as well as rural and urban areas—have come to reflect the partisan makeup of different parties. We now have heavily Democratic urban areas and heavily Republican rural areas. This is partly enabled by the fact that people tend to move into neighborhoods with others who are like themselves. As a result, you get social sorting that reinforces what happens online, where people similarly find their way into virtual communities that mirror their own demographics.

The second is party sorting, as we describe it in political science. Party coalitions underwent a sorting process beginning in the 1960s and 1970s with the signing of civil rights legislation. From that period forward, the Democratic Party—which had been a coalition of liberal elites in blue areas and, if you like, very conservative, racially conservative Southern Democrats—broke apart. Essentially, the social conservatives, and racial conservatives in particular, moved to the Republican Party, while liberal Republicans shifted to the Democratic Party.

As a result, the parties—rather than remaining more heterogeneous and containing internal breaks within their coalitional structures—became more ideologically consistent along lines of social and political liberalism versus conservatism.

Then there are factors outside the political process per se, though they are partly the result of policies we passed. One is the incredible rise in inequality, largely based on education, as the American economy became increasingly service-oriented and high-tech. Another is the change in immigration policies during the Civil Rights era, which opened the country to groups from all over the world and increased the racial diversity of the United States. That trend continues, partly because once immigrant groups arrive, they tend to have higher birth rates; even if immigration were to be curtailed, diversity would still grow.

Finally, there are the residual racial tensions from the earlier period, particularly around African Americans and, to some extent, Latinos. So yes, Trump made things worse—but crucially, there were demographic and political trends that preceded him and made his rise possible.

Grievance Politics and the New Republican Base

The contemporary Republican coalition increasingly rests on rural, white, non-college-educated constituencies mobilized through identity-based appeals rather than policy commitments. How has this demographic and geographic consolidation reshaped the movement’s ideological core, and to what extent has the strategic shift toward cultural grievance politics weakened traditional party mediation and fostered extra-institutional ecosystems like the alt-right and online mobilization networks?

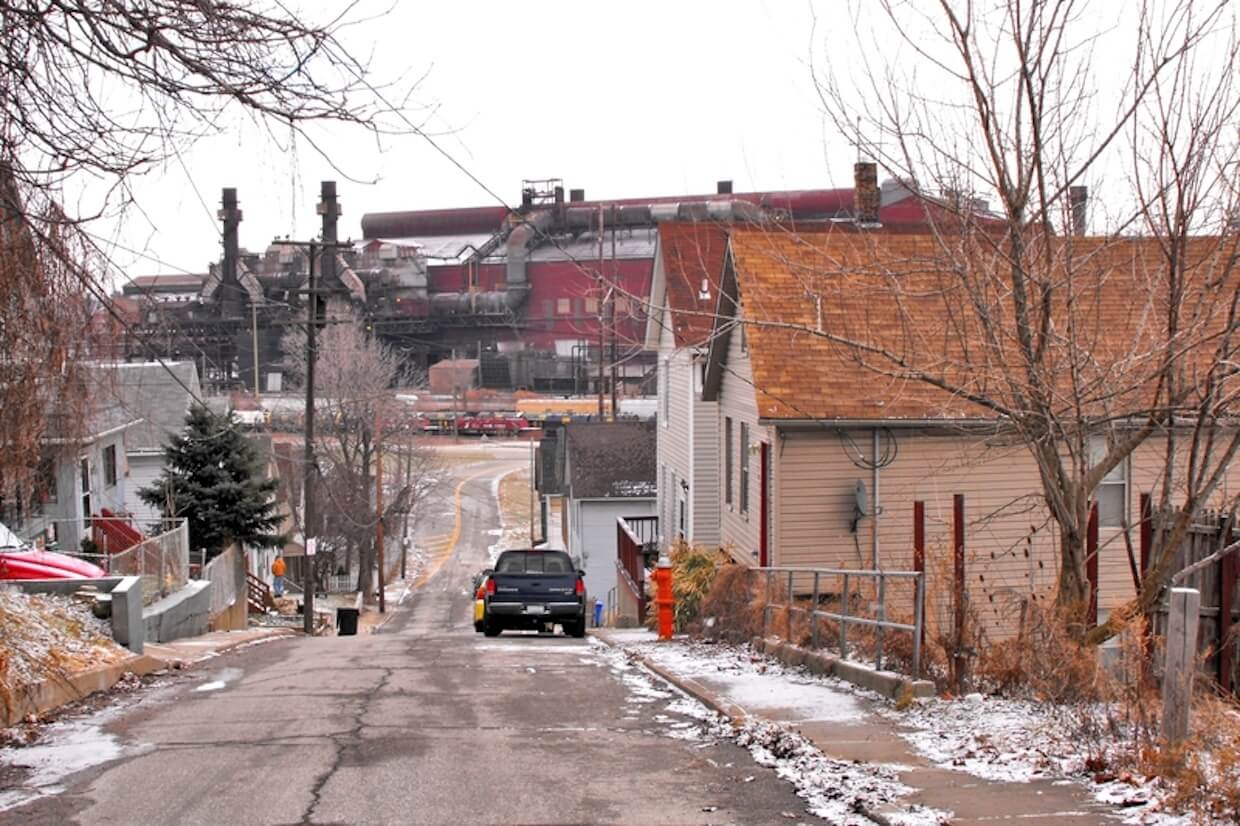

Professor Bruce Cain: Yes, and again, this is another one of these underlying trends that really is so critical. I’m an old man, and when I was growing up, there was more of a working-class versus non-working-class managerial divide in American politics. Today, it’s much more college-educated versus not college-educated. The problem for the Democratic Party is that, while there are a large number of college-educated people in the United States, the percent of people who’ve graduated from college is about 37%, and those who do not have a college education make up about 60%.

What that means is that, as we moved away from manufacturing, particularly in the middle of the country, we were taking a whole bunch of jobs—union jobs and well-paying non-white-collar jobs—and giving them over to other countries. Our free trade policies were undermining not only the economic basis of the middle of the country but also that of blue-collar workers throughout the United States.

I believe one element of this is just the anger about downward social mobility on the part of people who do not have a university education. But you also mentioned, and I think it’s right to say, that there’s been a shift in terms of cultural grievance. Part of it is that, along with the economic downward mobility, comes social and political loss of power and loss of status, and that certainly contributes to the grievance that you’re talking about.

But there was also the fact that the court got way out ahead on abortion policy and took it away from the states, nationalizing a policy I tend to agree with, but nonetheless, many Catholics and many fundamentalist Protestant groups don’t agree with, which is the right to abortion. Abortion really played a major role, on top of the racial divisions, in creating a divide between the Democratic and Republican Party.

So, yes, absolutely, I think grievance politics is now a very important part of what we’re talking about here.

Harnessing Crises for Authoritarian Ends

Trump’s response to events such as the Charlie Kirk assassination reveals how crises can be harnessed to justify extraordinary measures. How would you situate Trump’s use of crisis narratives within classical authoritarian playbooks—such as “Reichstag fire” strategies—and do you see this as a deliberate authoritarian project or an improvisational charismatic populism that nonetheless has authoritarian consequences?

Professor Bruce Cain: That involves psychoanalyzing Mr. Trump, which unfortunately I can’t do. I think some of it is absolutely a deliberate strategy, but some of it is simply that this is not a man who controls his emotions very well. And perhaps, if he follows the path of his father into dementia, we may see more of this kind of emotional rollercoaster, because that’s one of the features of dementia. So, believe me, we’re worried about that in the United States.

There’s no question that, whether by instinct or by deliberate strategy, Trump is playing the classical authoritarian game. There’s no doubt that’s what he’s trying to do. It suits the way he has run his companies, and it suits the kinds of leaders he admires in other countries. He’s essentially following in their footsteps.

But I will say this: so far, he is tracking other presidents—the three presidential administrations, including Trump One—in terms of his popularity with the public. His numbers have been dropping; he’s now at about 41% favorability, which is where he was during Trump One, when he suffered a major setback in the by-election that followed his 2016 victory.

There are also many more courts now, particularly below the Supreme Court level, that are blocking his attempts to implement authoritarian measures, whether involving the use of troops or emergency clauses. Admittedly, we still have to wait for the Supreme Court to weigh in on these matters, but it seems the Court is waiting to hear from many of the district and appellate courts. If I were the Trump administration, I would suspect he’s going to lose a fair number of these cases.

Then, of course, the press corps are increasingly angry with him. Most recently, when the Defense Department tried to get journalists to sign pledges not to use leaked information, virtually the entire press—including the right-wing press—rejected the move.

So, yes, there’s no question that he wants to play the authoritarian playbook. The question is whether that’s actually possible in the United States, even in these very divided times.

Trump’s Legacy and the Institutionalization of MAGA

Do you view the MAGA movement as populism evolving toward a stable authoritarian formation, potentially institutionalized through mechanisms like Project 2025, or as a personalist phenomenon tied to Trump’s leadership that may dissipate with his exit? What institutional or cultural legacies do you expect to persist beyond his tenure?

Professor Bruce Cain: Again, it’s a mix. You can’t take Trump out of the equation. His ability to use social media, the fact that he is a self-financed candidate who was able to launch his campaign with his own money, and his status as a TV star on a show that portrayed him as a strong business leader—even if we think that image was fake—all of these factors mattered. It’s not clear that anyone else could have brought all those elements together, so there is a unique dimension to Trump in that regard.

But the reality is that there was a base composed of people who were unhappy about many of the social issues we’ve been discussing and people who were experiencing downward mobility. There was always the potential to mobilize this base, which we now call the Make America Great Again base, or MAGA base. That base is a critical part of the equation, and it likely won’t disappear, even if Trump decides not to contest the next presidential election because he believes he can run a third time. The Constitution says no. But the MAGA base will remain, no matter what happens to Trump.

Another issue we face is the extremely close contestation between the two parties. Many of our most stable periods have occurred when one party held clear dominance. In the 1960s and 1970s, it was the Democratic Party; during the Reagan years, it was the Republican Party. Today, neither party has a firm grip, which means we’re likely to see a lot of back-and-forth, closely contested elections. This dynamic creates opportunities for mischief, as both sides try to extract tactical and strategic advantages from the system.

So yes, much of this will endure even after Trump moves on. But Trump brings a unique element to the equation—one that I don’t see anyone else in the Republican Party being able to duplicate.

Militarizing Politics: A Break with American Norms

Trump’s willingness to deploy more National Guard in major Democratic-run cities raises questions about federal coercion, politicization of armed forces, and the subversion of local democratic autonomy. How might such measures operate within an authoritarian power-consolidation strategy, particularly in delegitimizing urban, racially diverse political centers framed as “internal enemies”?

Professor Bruce Cain: We’re worried about that. There’s no question that what’s different about Trump is his attempt to incite division rather than suppress or mediate it, along with his use of extra-controversial methods—going around the rules in dubious ways—and waiting for the courts to slap his hand. The courts, of course, are very deliberate; they will examine these matters carefully before making decisions that will shape the future.

This is what’s troubling. Compared to Trump One, there is much more bullying. There was always a bullying element in Trump One, but he has really taken that a step further. He’s now extending it into the states, which is a major violation of American political norms. It would be the equivalent of the EU entering Spain, France, and other European countries and deploying military forces to enforce EU policies.

In the United States, we believe that states have sovereign powers over areas such as education, policing, fire services, and other local affairs. For Trump to coerce at that level is both disturbing and highly unusual. I believe it will ultimately be struck down by the courts, but it will take time before these issues are fully litigated.

DEI Backlash and the Toleration of Extremism

“White replacement” and “white genocide” conspiracies have become central to far-right mobilization. How integral are these narratives to sustaining the contemporary Republican coalition, and how do they interact with institutional party strategies versus grassroots extremist currents?

Professor Bruce Cain: For the MAGA base, these narratives are absolutely essential. The MAGA base constitutes, at best, around 40%, but more likely closer to 30% of the Republican Party’s support. I don’t believe that the white replacement and white genocide conspiracies are significantly influencing traditional Republicans. What may resonate with them, however, is concern over what they perceive as overly zealous efforts to implement Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives. But that doesn’t mean they’ve embraced white nationalism.

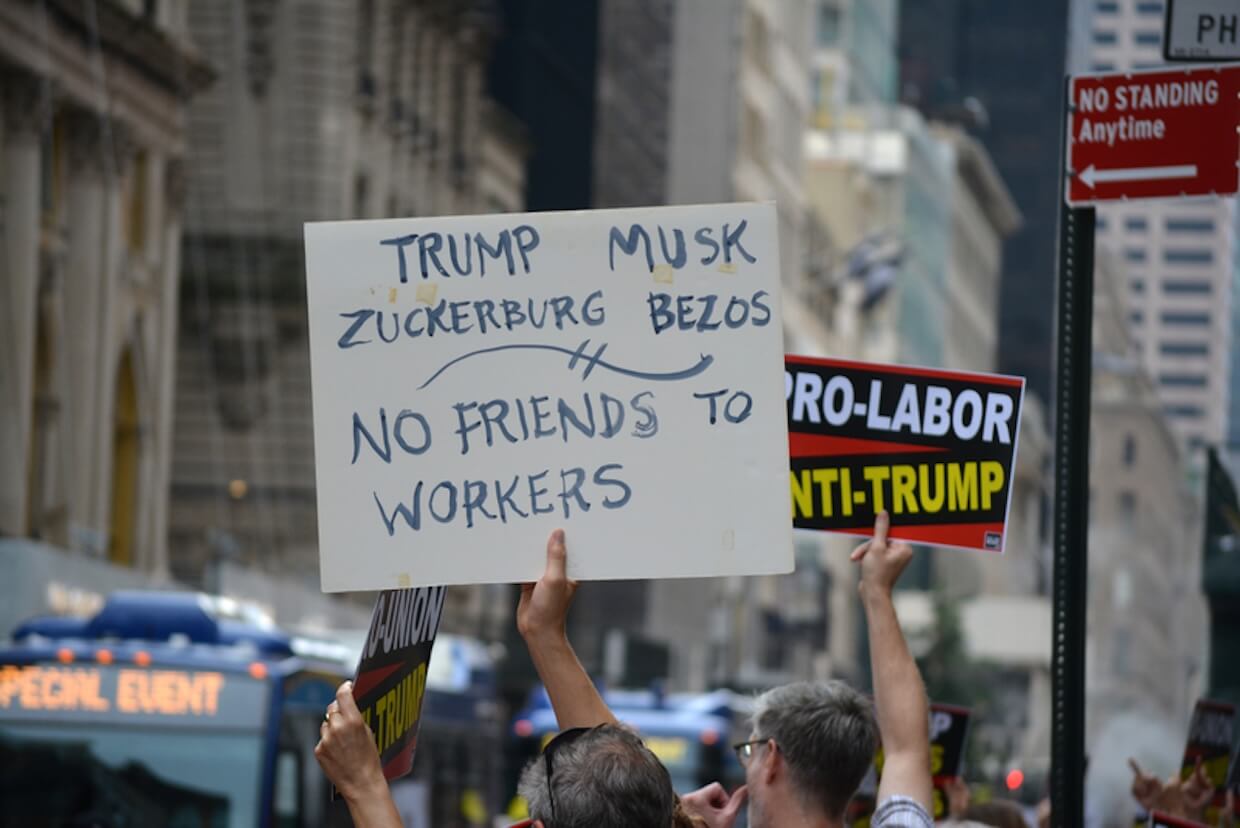

The Republican Party should be seen as a coalition between those who believe in the white nationalist agenda that Trump is promoting and traditional Republicans who supported him for tax cuts and regulatory relief. Many in the latter group were willing to tolerate the former, using perceived DEI overreach as a justification for accommodating the white nationalist wing of the party.

As a result, these groups exist in an uneasy coalition within the Republican Party. However, I don’t believe the party as a whole is fully aligned with the MAGA agenda on this issue.

The Secular Strongman of a Sacred Cause

The intensified fusion of evangelical Christianity and Republican politics under Trump has transformed the political theology of the Right. How has this religious alignment shaped authoritarian tendencies, policy radicalization, and the sacralization of political conflict?

Professor Bruce Cain: The secular–religious divide in America has deepened over the lifetime of many of us. Those of us who were boomers and grew up in the 1960s and 1970s remember a time when the Democratic Party, under Carter, for example, had an evangelical wing. The abortion issue and subsequent legal decisions created a separation, and George Bush Jr. then brought more evangelicals over to the Republican side.

Trump is not a religious man. He pretends to be, but I don’t think anyone seriously believes he is a pious human being. It is striking that perhaps one of the most secular and morally compromised figures imaginable has become the leader of the religious right. But they view him much like someone views their divorce lawyer: they don’t care about the lawyer’s personal morality as long as they get the divorce.

Trump functions in the same way. They know he’s not a decent person, but they appreciate that he stands up for them, and they overlook the fact that he is anything but a religious man himself.

Strategic Ambiguity on White Nationalism

Republican elites have alternated between embracing and distancing themselves from alt-right and white supremacist movements. How should we interpret this oscillation—tactical ambiguity, strategic co-optation, or deeper ideological convergence?

Professor Bruce Cain: I don’t think it’s completely resolved how far they’re willing to go with this sort of white nationalism. I know too many educated Republicans who don’t share that perspective. For example, at Stanford, one of the most powerful people on campus is the head of the Hoover Institute, Condoleezza “Condi” Rice, an African-American woman who is widely respected. She certainly doesn’t tolerate white supremacist beliefs.

So, it’s an uneasy alliance, and as I mentioned before, it’s justified for the time being because there’s a belief that Democrats went a little too far in promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion measures, and that affirmative action went too far as well—leading some to feel that fairness has been denied in the present to redress past injustices.

There’s a clear distinction between Republican skepticism about DEI and outright supremacist thinking. It’s really a small part of the base that genuinely holds those extremist views. This makes for an uneasy coalition, which could become problematic at some point in the future—perhaps as soon as the next presidential election.

The Activist–Billionaire Nexus in GOP Politics

Drawing on your work on party autonomy, how has Trumpism altered the internal structure and strategic independence of the Republican Party? Has it hollowed out institutional authority or merely displaced it toward charismatic leadership and movement actors, especially within a nomination system that was reformed to democratize candidate selection but arguably enabled populist capture?

Professor Bruce Cain: There’s definitely, again, an element that is peculiar to Trump and his very strong bullying methods. That’s enabled him to capture the party. But if we step back, we see that there are longer-term trends that made it possible for him to do this. Right at the top of the list is social media. Social media, as we’ve seen, has become a powerful tool for bullying—everything from doxing to the ability to publicly shame people to mobilizing crowds instantaneously. All of these dynamics have made bullying and intimidation much stronger, not only in politics but also in the lives of our children and in our communities. Trump was definitely a beneficiary of that.

But there were also things we did through political reform that weakened parts of the party. In America, we think of the party as having three components: the party in office, namely the partisanship of the officeholders; the party in the bureaucracy, which consists of the people in the Republican National Committee (RNC), the Democratic National Committee (DNC), and the 50 state parties—those who run the machinery of the party; and finally, the activists.

To make a long, complicated story short, political reforms have strengthened the activists, who are by far the most ideological component of the electorate, while weakening the power of officeholders. Congress is now so afraid of party primaries because primaries do not attract all voters; they attract only the most partisan, activist ones. As a result, the control activists have over the primaries skews both parties to either the left or the right.

Another key factor is that the Supreme Court has allowed wealthy individuals to spend as much money as they want, creating almost limitless self-financing. This helped Trump significantly, as he was able to use his own money to catapult himself into the primaries. There is now far more independent spending, which essentially dwarfs the money given directly to candidates. We are awash in ideological and interest group money, and our inability to control campaign finance has unquestionably helped Trump and made the situation much worse.

Emergency Powers and Democratic Stability

The rise of executive-centered partisanship has weakened Congress and elevated the presidency as the primary partisan engine. Do you see this imbalance as reversible through institutional reform, or has it become structurally entrenched within the constitutional order?

Professor Bruce Cain: We’ll know a lot more about the answer to this question over the next year, as the Supreme Court will have to decide how far emergency powers can be used—the use of emergency powers to suspend normal processes, the use of impoundment activities (i.e., deciding upon entering office not to spend the money allocated by the previous Congress), and how much authority the president has to remove people in the bureaucracy who are nonpartisan rather than political appointees. In other words, how much of the Progressive Era reforms designed to create a nonpartisan bureaucracy can be undone.

If the Court condones these actions, it will be a case of monkey see, monkey do, because the Democrats will take whatever powers are given to the president to politicize everything, use emergency powers, and undo everything that Trump is doing. The Democrats will do the same thing, which means there will be far more instability in American positions vis-à-vis Europe, trade, and climate change. Essentially, the system will become much more schizophrenic and variable, and I believe this will ultimately undermine capitalism, investment, and infrastructure. Whether we are headed in that direction—and whether it becomes permanent—will be decided by the Supreme Court over the next year or two.

Money as Speech—and as a Tool of Power

In your work on “dependence corruption,” you highlighted how financial flows shape representation. How do emerging funding ecosystems—around MAGA media, Christian nationalist donors, tech billionaires, and PACs—challenge existing regulatory frameworks and deepen authoritarian tendencies within the movement?

Professor Bruce Cain: I do believe that America, because it has a very liberal interpretation of the First Amendment—i.e., because we believe that money is speech and that we can only restrict it under the narrowest purposes, namely to prevent quid pro quo corruption, meaning money that’s given directly to a candidate—has opened up the floodgates to a lot of money. That can still work if the money is balanced on both sides, and on many issues, that’s true. But what we’re seeing, for example, with digital currencies is that Trump has brought in lots of billionaires—tech billionaires—who want to create meme coins and invest in large server farms to generate value for digital currency.

All of these developments are tied not only to corruption stemming from campaign contributions but also to Trump himself cutting deals, investing in currency, and then making policy that favors those investments. We’re seeing in America now a level of corruption that we didn’t think was possible after the reforms of the 1970s. It’s approaching the levels of the 19th century, with people getting into office or power and then using it to make themselves richer. This is a major concern, and many of us in the legal and political science communities will be thinking seriously about how to strengthen the system against it.

Reinforcing Democratic Guardrails

Lastly, given these structural, ideological, and institutional transformations, what democratic guardrails or institutional reforms do you view as most urgent to counteract potential authoritarian consolidation on the American Right? Are there specific vulnerabilities—such as in party regulation, executive power, or information ecosystems—that should be prioritized?

Professor Bruce Cain: I would say that many people in my world of political reform are going to try to restore some of the institutions we once had, like the filibuster—i.e., supermajority votes that aim to create bipartisanship. They’re going to try to bring that back, but I think this runs up against the underlying political culture in America right now. Where the Court really needs to draw the line to save American democracy is on executive actions—specifically, the degree to which the President can act unilaterally by imaginatively reinterpreting existing legislation and issuing executive actions.

Secondly, emergency provisions. If everything is an emergency, then nothing is a democracy. That’s essentially where we’re headed if we’re not careful, because political parties can pretty much declare anything an emergency—whether it’s somebody being attacked in a city, an immigration issue, or economic downturns. If everything qualifies as an emergency, democratic norms erode. That is a major vulnerability that needs to be addressed.

Lastly, for both the United States and within the EU, there must be a clear understanding that states’ rights—the ability of states to check the federal government, to serve as laboratories of innovation, and to act differently from the federal government—are critically important. It’s essential that the Court continues to recognize the importance of state sovereignty as granted under the Constitution.

These are the most important steps to take right now, and Trump has made it very clear that we need to shore up both judicial interpretations and, potentially, some of the statutory and constitutional language associated with these issues.