Please cite as:

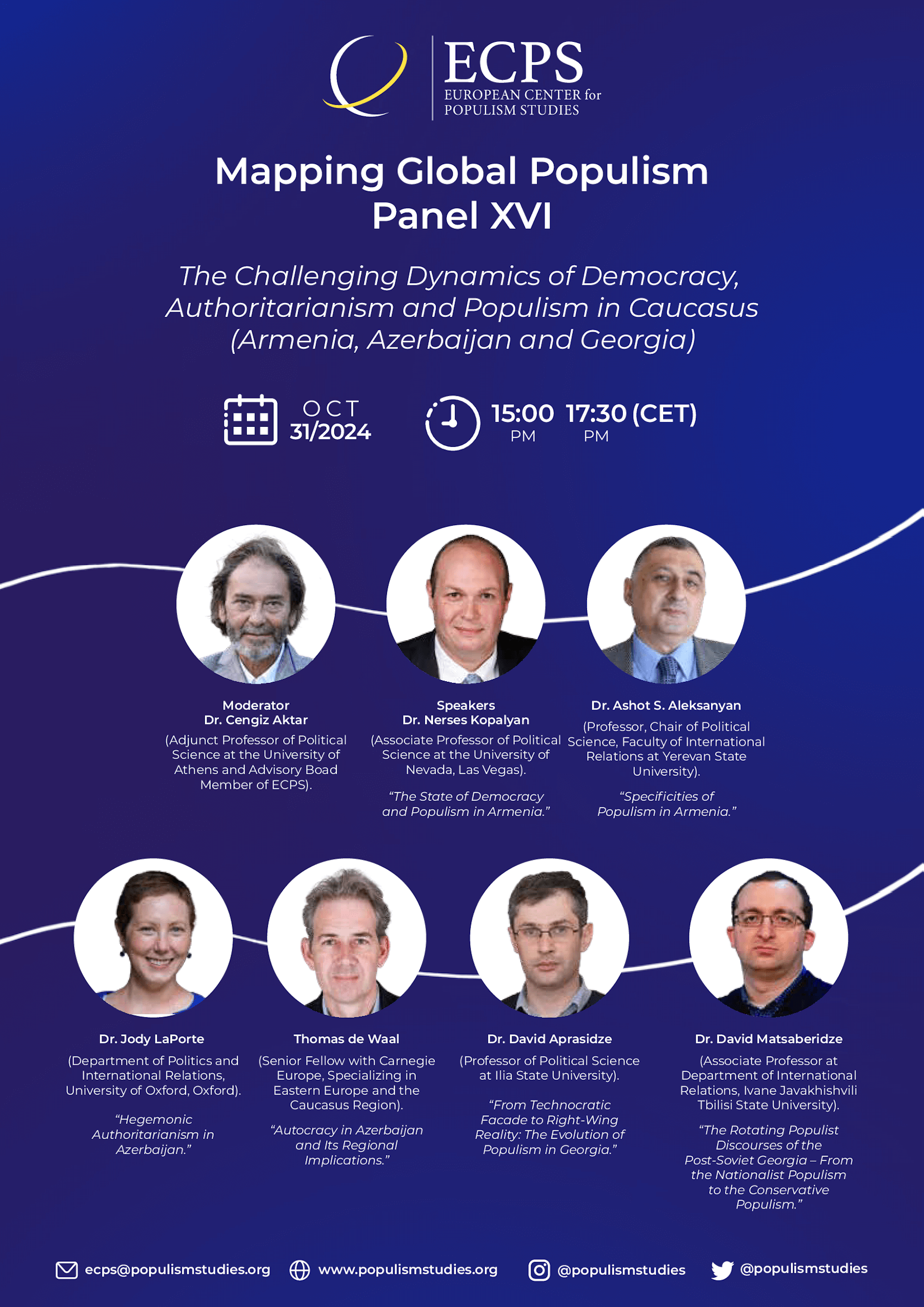

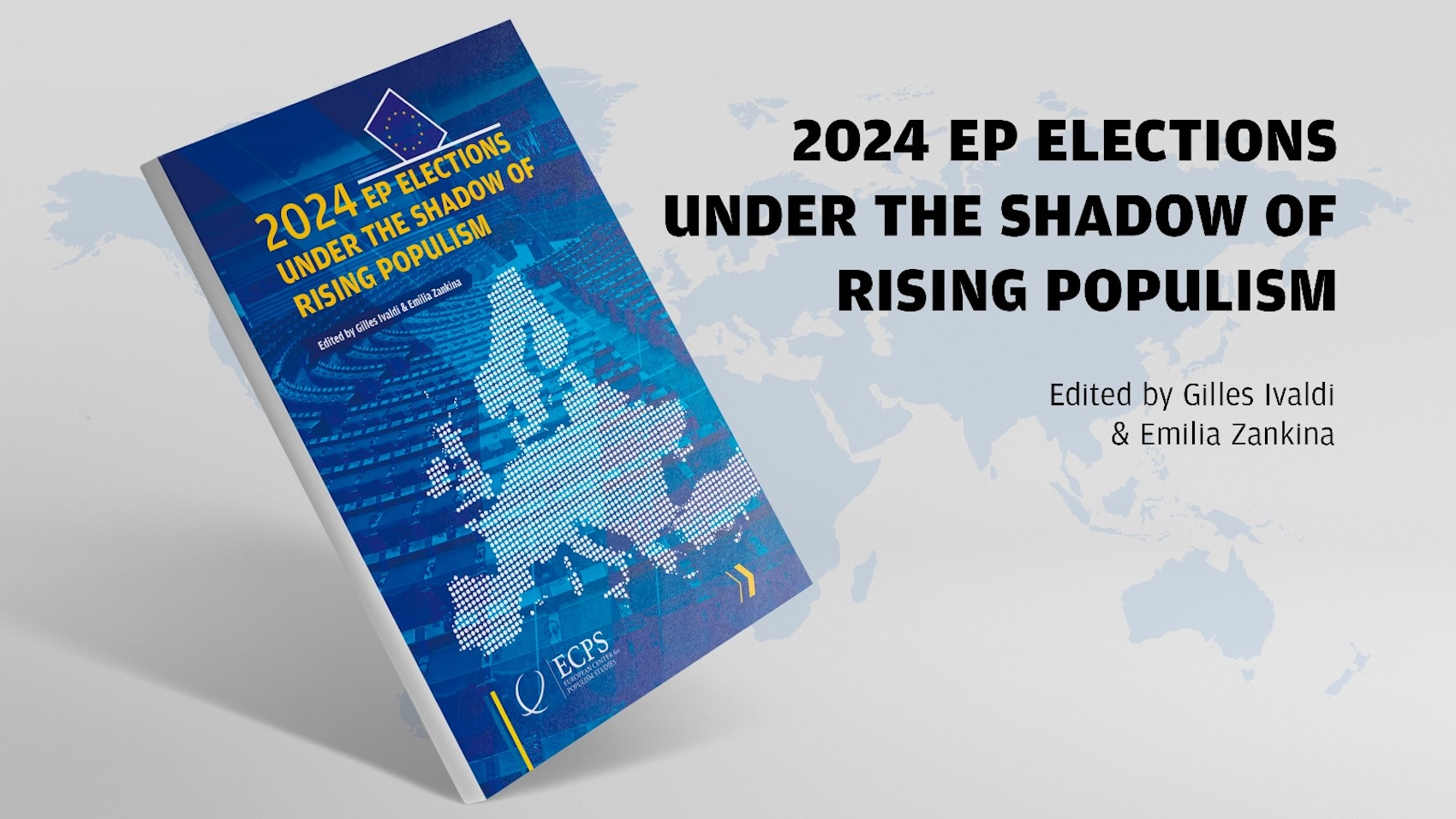

Ivaldi, Gilles & Zankina, Emilia. (2024). “Introduction: The ECPS Project ‘Populism and the European Parliament Elections 2024’.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0060

Abstract

This report analyzes the performances and impact of populist parties in the 2024 European elections. Drawing from the analyses of country experts, we provide an account of how populist parties across the spectrum performed in each of the EU’s 27 member states, looking at the campaign, issues and demand for populist politics in each country separately and the challenges that populist party success more broadly bears for the future of the EU. In this introductory chapter, we briefly define populism, provide a topographic map of populist parties across all EU member states ahead of the 2024 European elections, and review the main drivers of populism identified in the literature. We then turn more specifically to the general context and outcome of the 2024 EP election, assessing the hypothesis of another ‘populist wave’ while also looking back at the 2019 election to compare populist party success over time.

By Gilles Ivaldi* (Sciences Po Paris–CNRS (CEVIPOF), France) & Emilia Zankina* (Temple University, Rome, Italy)

Introduction

Throughout the first two decades of the 21st century, populism has emerged as one of the most significant global political phenomenons, deeply affecting electoral politics in democracies across the globe, both new and consolidated (Moffit, 2017; De la Torre, 2019). In Europe, populism has become a major force, reshaping the political landscape and discourse of the European Union and most of its member states in unprecedented ways. Over the years, the impact of populist parties has been felt both at the level of domestic and European politics, increasingly putting pressure on more established mainstream parties, particularly at the right of the political spectrum (FEPS, 2024).

Populism is found in different locations in the party system, predominantly at the far left and far right of the spectrum (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018). The PopuList database of populist parties illustrates the rise in support for populist, far-left, and far-right parties in Europe since the early 1990s (see Figure 1). Such parties have made significant electoral gains in recent years. They have joined coalition governments in several countries, including Italy, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Austria, more generally reflecting the mainstreaming of their ideas and themes in party politics and public opinion (Muldoon & Herman, 2018; Schwörer, 2021; Bale & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2021).

Populist performances typically vary across parties and contexts, reflecting the complex interplay between structural and contextual factors. As Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos (2020) show, electoral support for radical parties is rooted in structural factors, but their translation into electoral choice is conditioned by political discontent that originates in specific political dynamics. While contemporary populism is generally seen as a response to a wide range of socioeconomic and cultural grievances and issues (Norris & Inglehart, 2019; Guriev & Papaioannou, 2020; Rodrik, 2021), it can also be seen as an expression of political discontent largely dependent on the national political cycle and the shorter-term country-specific opportunities produced for populist mobilization.

The analysis of the European Parliament elections of June 2024 thus provides a unique opportunity to simultaneously assess the current wave of populism across all 27 European Union (EU) member states. With European Parliament (EP) elections all taking place at about the same time, we can look more closely and comparatively at the current wave of pan-European populism, its size, dynamics and impact on national polities and, ultimately, on the EU.

This report analyzes the performances and impact of populist parties in the 2024 European elections. Drawing from the analyses of country experts, we provide an account of how populist parties across the spectrum performed in each of the EU’s 27 member states, looking at the campaign, issues and demand for populist politics in each country separately and the challenges that populist party success more broadly bears for the future of the EU.

In this introductory chapter, we briefly define populism, provide a topographic map of populist parties across all EU member states ahead of the 2024 European elections, and review the main drivers of populism identified in the literature. We then turn more specifically to the general context and outcome of the 2024 EP election, assessing the hypothesis of another ‘populist wave’ while also looking back at the 2019 election to compare populist party success over time.

Mapping European populism(s)

Mudde (2004) defines populism as a ‘thin-centered ideology’ that ‘considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’. Populist parties champion the cause of the ‘common man’ against what is perceived as a detached and self-serving political elite. While there are other ontological approaches to populism – e.g., political discourse (Laclau, 2005), political strategy (Weyland, 2001), and performance (Ostiguy et al., 2020) – these different traditions of research generally converge towards the same common essential attributes underpinning populism (Olivas Osuna, 2021). Moreover, the ideational approach allows one to connect the supply and demand side of populism and to study the diversity of its manifestations across Europe.

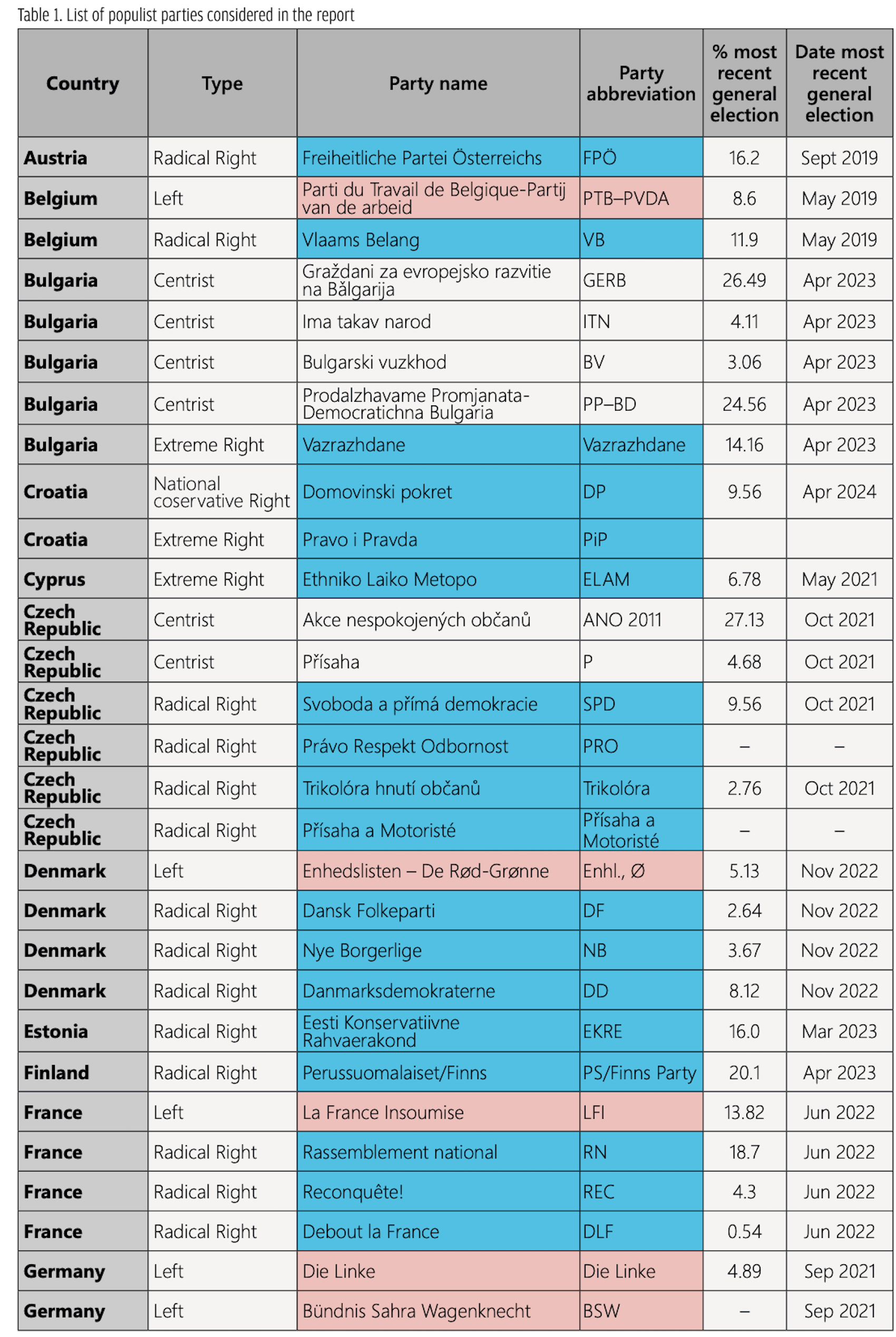

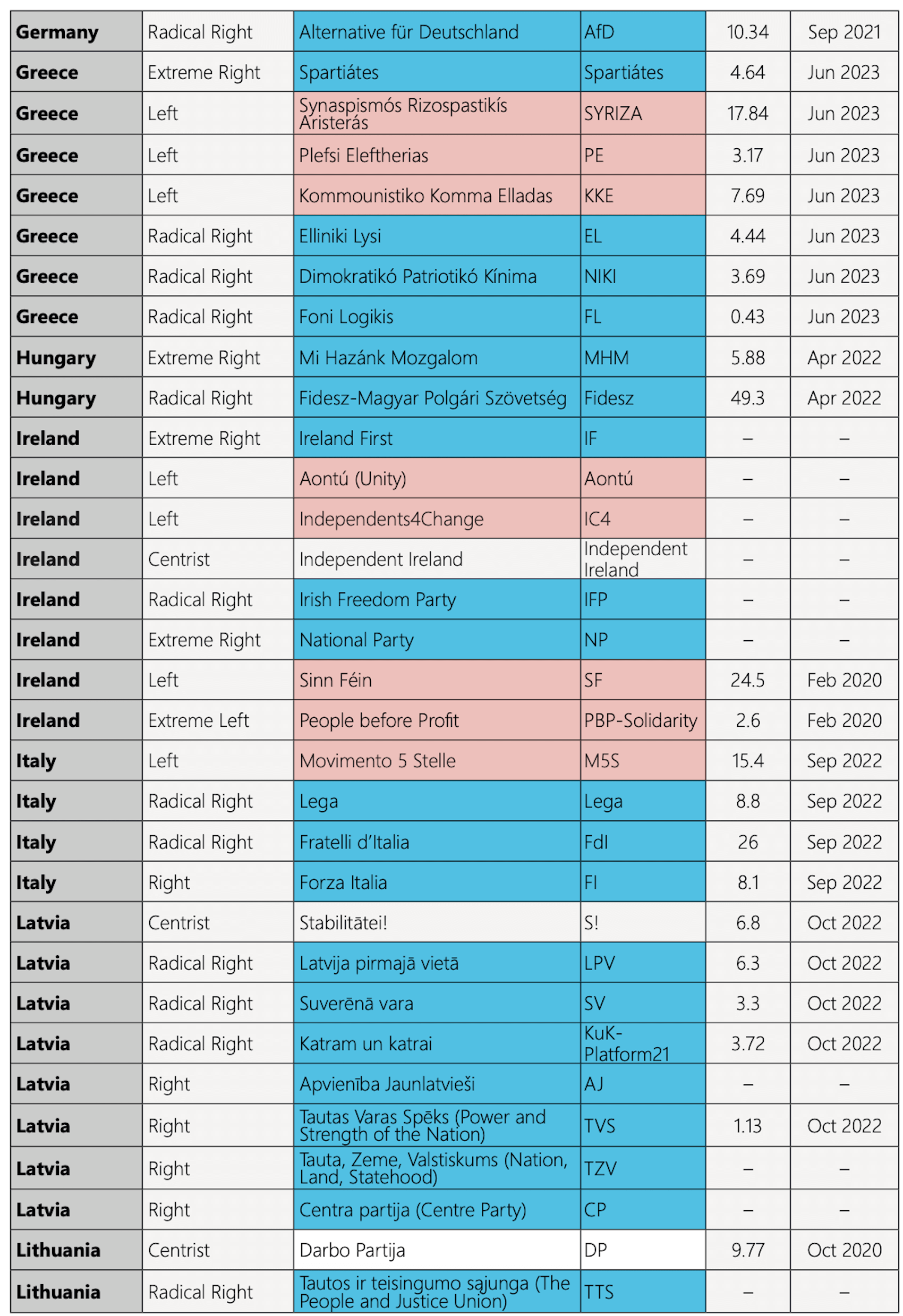

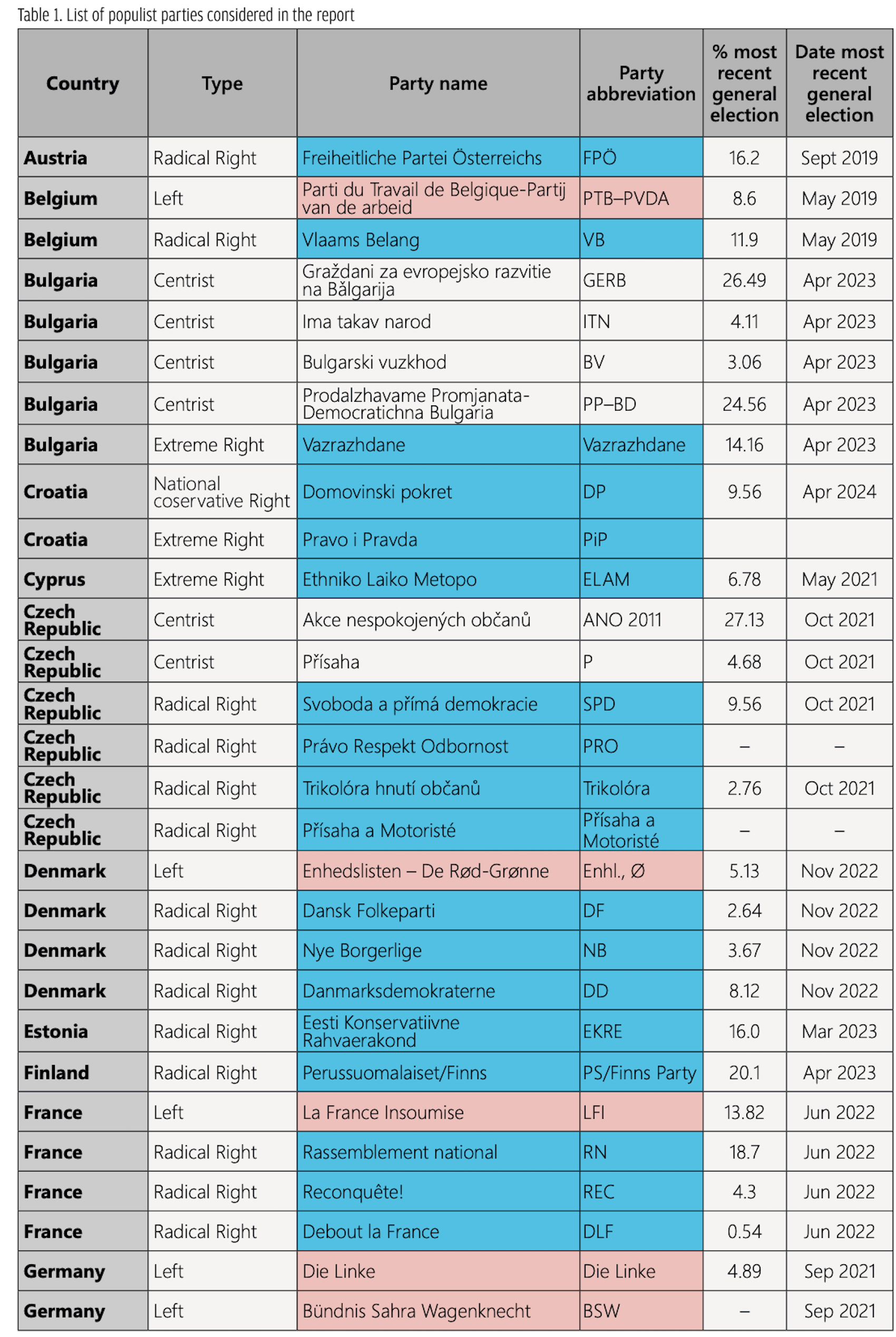

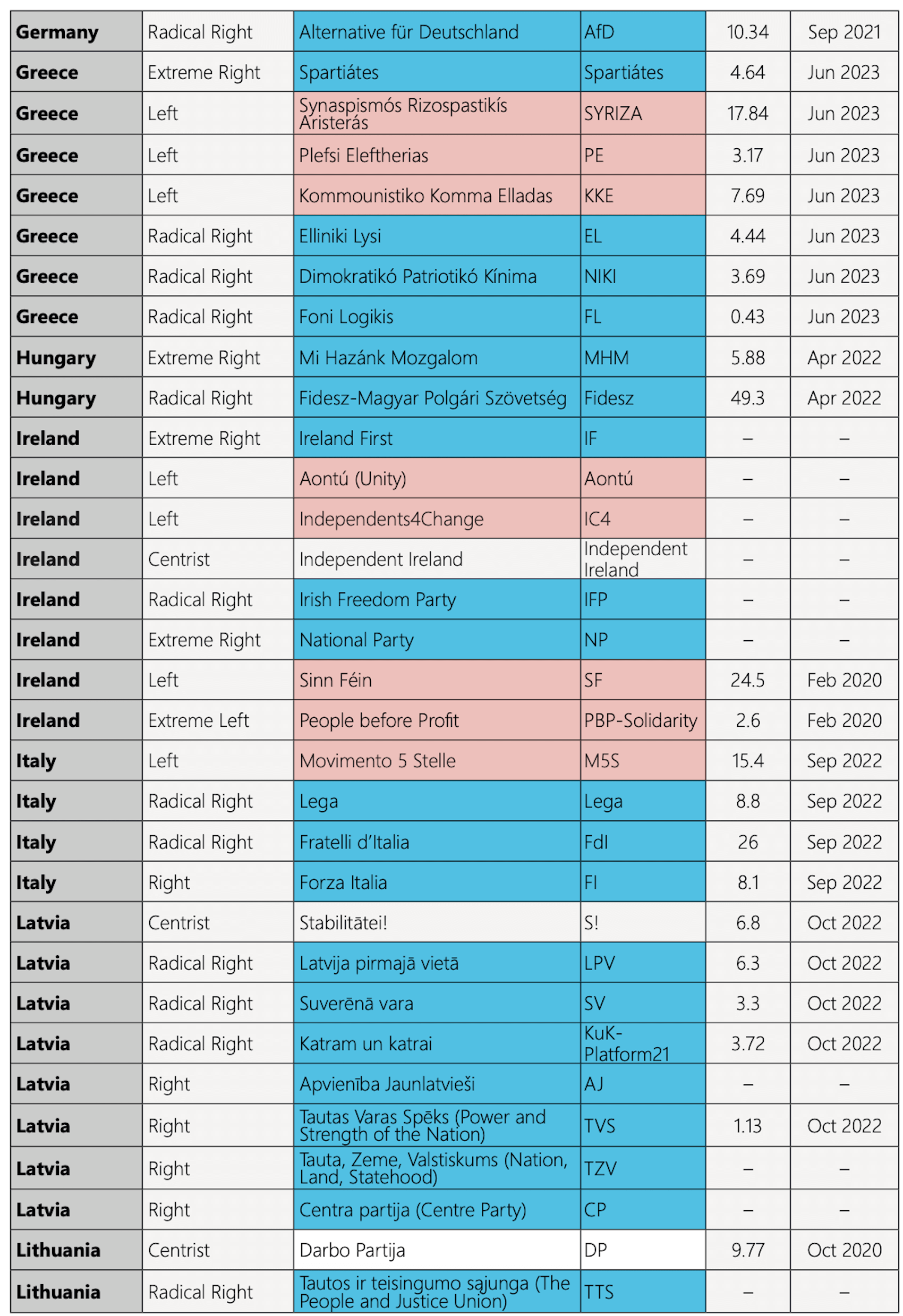

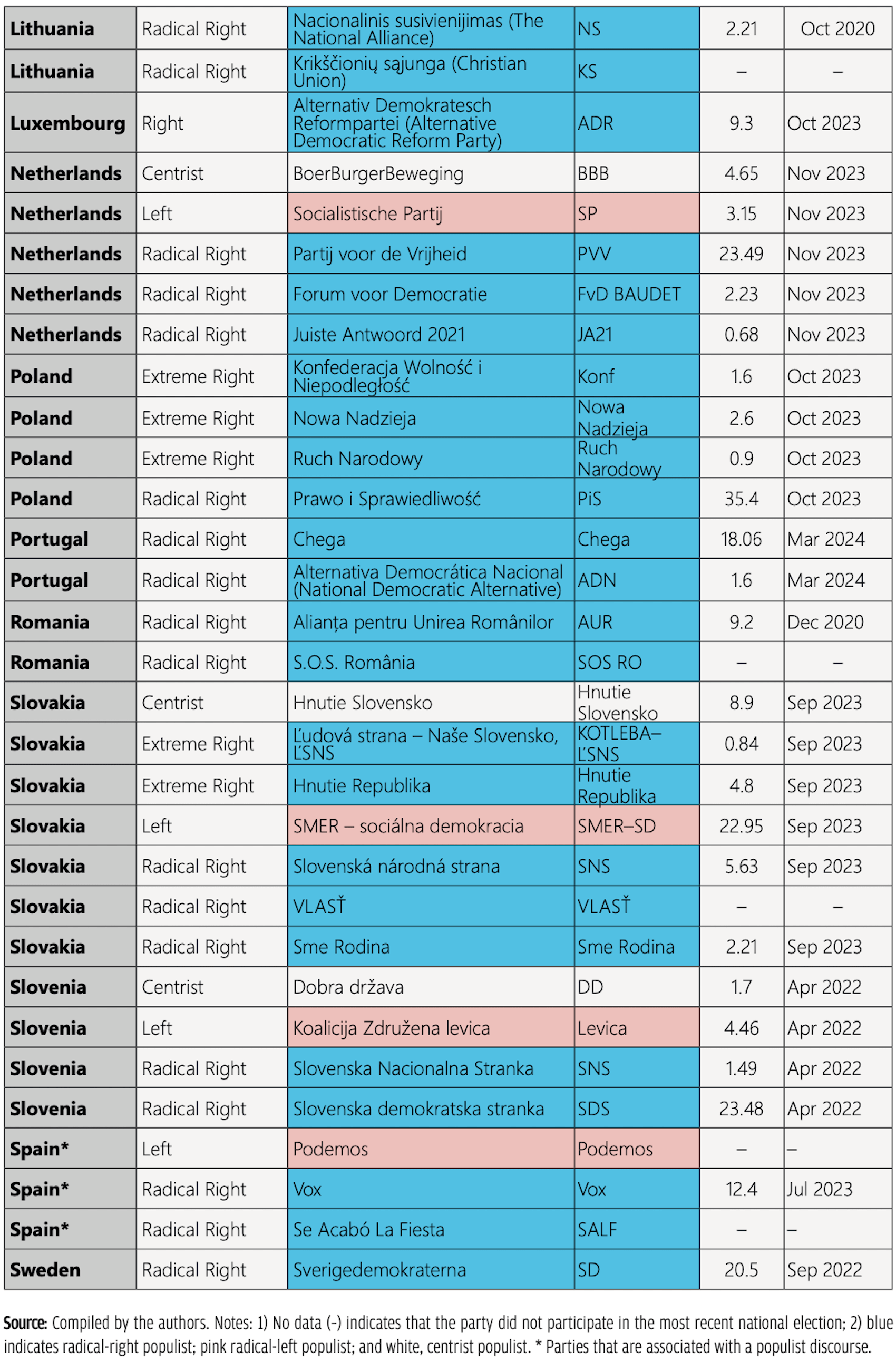

In the European political landscape, populism manifests itself in a variety of parties across the political spectrum, from left to right (Ivaldi et al., 2017; Taggart & Pirro, 2021). In Eastern and Central Europe, populism may also be found across a range of ‘centrist’ anti-establishment parties located inside and outside the mainstream (Hanley & Sikk, 2016). Such diversity is shown in Table 1, which provides an overview of the leading populist parties in the current European political landscape.

Table 1 illustrates the diversity of populism. Overall, there were about 90 populist parties across all EU member states on the eve of the 2024 European election, with varying ideological profiles, backgrounds and electoral sizes. Essentially, populism was found both left and right of the European political spectrum, as well as at its centre, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

Table 1 illustrates the diversity of populism. Overall, there were about 90 populist parties across all EU member states on the eve of the 2024 European election, with varying ideological profiles, backgrounds and electoral sizes. Essentially, populism was found both left and right of the European political spectrum, as well as at its centre, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

On the radical right, populism is typically combined with exclusionary nativism and authoritarianism, whereby the people and the elite are primarily defined along cultural lines (Mudde, 2007). Radical-right populist parties essentialize migration not only in their nativist rhetoric but also portray it with terrorism and crime, and in this way, it is put forward as a security issue, as was the case during the Paris and Brussels attacks in 2015–2016 (Mudde, 2019). Such populism is found in parties like France’s National Rally (RN), Lega (formerly Lega Nord) and Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia, FdI) in Italy, and the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ). The nativist and authoritarian ideology of the PRR is also found in ‘radicalized’ conservative parties such as Poland’s Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) and Hungary’s Fidesz, which have turned to a populist radical right strategy over time (Buštíková, 2017: 575).

The populist radical left has, on the other hand, a universalistic profile embracing a more socially inclusive notion of the people, who are essentially pitted against the economic elites (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018; Lisi et al., 2019). In Europe, left-wing populism has been particularly electorally successful in the wake of the 2008 global economic crisis (Katsambekis & Kioupkiolis, 2020). Economic issues, bailouts, and austerity programs were the main driving forces behind a transformation of the radical left emphasizing distributive issues in Eurosceptic populist directions (Gómez-Reino Cachafeiro & Plaza-Colodro, 2018). Parties such as the Spanish Podemos, SYRIZA in Greece, or Germany’s Die Linke (The Left) are examples of this phenomenon. In those countries, however, there has been a decline in the electoral support for parties of the populist left since 2019 (Ivaldi, 2020).

Finally, in CEE, populism often manifests itself in the form of ‘centrist’ anti-establishment parties (Učeň, 2007; Hanley & Sikk, 2016). Such parties operate in the more volatile party system of the former Communist bloc, where political instability is a long-term phenomenon. They focus on challenging the existing political elite and fighting corruption, and they can be found across the entire political spectrum, both within and outside the ideological mainstream (Engler et al., 2019). This type of populism is found in parties such as Slovakia’s Ordinary People and Independents (OL’aNO), the movement of Paweł Kukiz (Kukiz) in Poland and Change Continues (Prodalzhavame Promyanata, PP) in Bulgaria. Looking more specifically at the Czech Republic, Havlík (2019) sees the rise of the Action of Dissatisfied Citizens 2011 (ANO 2011) as a case of ‘centrist technocratic populism’ based on a denial of political pluralism, anti-partyism, resistance to constitutionalism and the embrace of majoritarianism. In Western Europe, the Italian M5S has been seen as a case of ‘centrist populism’, which does not display the typical ideological profile (Mosca & Tronconi, 2019; Pirro & Van Kessel, 2018).

The populism-Euroscepticism nexus

Given their inherent anti-elite and anti-established stance, populist parties in the European context are also often Eurosceptic. Kneuer (2018) emphasizes such a ‘tandem’ of populism and Euroscepticism as one unifying feature of all successful populist parties in Europe, reflecting in her view the formation of a new transnational cleavage cross-cutting the traditional left-right axis.

A recent study examining parties in 30 European countries from 2018 to 2024 (Szczerbiak & Taggart 2024) finds 77 parties to be both Eurosceptic and anti-establishment. Szczerbiak and Taggart argue that the growth of European integration and its association with a series of crises, such as migration, the Eurozone, Brexit and COVID-19, has bred discontent that fostered anti-establishment positions and the demonization of the EU. At the same time, the study found clusters of parties that are anti-establishment but not Eurosceptic and parties that are Eurosceptic but not anti-establishment, arguing that the link is not always straightforward.

Meijers and Zaslove (2021) also examine populist parties’ positions towards European integration, similarly arguing for a nuanced picture, with some populist parties rejecting the EU outright while others are taking a reformist position. According to their study, populist parties such as the Dutch Freedom Party (PVV) and Forum for Democracy (FvD), the Alternative for Germany (AfD), Golden Dawn in Greece and Lega in Italy are highly Eurosceptic. Populist left parties, on the other hand, tend to be more moderate, with the Five Star Movement (M5S) being moderately Eurosceptic and Podemos and SYRIZA having moderate pro-EU positions.

Similarly, Pirro, Taggart and Kessel (2018) find differences between left- and right-wing variants of populist Euroscepticism. Examining the economic and financial crisis (the ‘Great Recession’), the migrant crisis and Brexit, they find left-wing populists attacking the EU’s ‘neoliberal’ agenda and austerity measures, while right-wing populists criticizing the EU on account of increased immigration and multiculturalism. Brexit, on the other hand, is portrayed ‘by various kinds of populist parties as a victory for the ordinary people against unresponsive elites and a rejection of the undemocratic and technocratic decision-making process at the EU level’ (Pirro, Taggart and Van Kessel, 2018). While Euroscepticism is not limited to populist parties alone, neither are all populist parties Eurosceptic. We see a strong correlation between anti-EU positions and populist parties, which is more pronounced to the right than to the left.

More recently, however, there has been a moderating shift in populist Eurosceptic politics both left and right of the spectrum. In the wake of the Brexit referendum of 2016, many populist parties have strategically abandoned their previous plans to drop the Euro or leave the EU altogether, turning to more nuanced or ambiguous positions vis-à-vis European integration in order to increase their appeal to moderate and pro-EU voters, and to collaborate with mainstream parties. As Van Kessel et al. (2020) note, the difficulties in the Brexit process may have dampened public demand for leaving the EU elsewhere in Europe, thus reducing the viability of ‘exit strategies’. Other studies suggest that populist parties, particularly of the radical right, have been shying away from hard Eurosceptic positions. Right-wing nationalist populist parties have adopted ‘alt-Europe’ counternarratives reflecting ‘a conservative, xenophobic intergovernmental vision of a European “community of sovereign states”, “strong nations” or “fatherlands”, that abhors the EU’s “centralized” United States of Europe’ (McMahon, 2021: 10). ‘Taking back control from Brussels’ has been observed to be a common stand of radical right-wing populist parties on the way to the 2024 EP elections (Braun & Reinl, 2023).

As McDonnell and Werner (2018) argue, populist radical right parties ‘remain flexible to perform significant shifts’ on the issue of European integration because of its relatively limited salience. The dampening of their Euroscepticism by populist parties may also be associated with office-seeking strategies. As Ivaldi (2018b) suggests, in the case of the French FN, governmental credibility and coalition potential have been two strong incentives for the FN to tone down its Euroscepticism since the 2017 presidential election.

Drivers of populism: structural and short-term factors

The economic crises of the past decade, coupled with the perceived threats posed by globalization and immigration, have created circumstances that allow for a surge in populist sentiments across various European nations. Populism, characterized by a general distrust towards traditional political institutions and an increasing polarization of society, is fuelled by a complex interplay of socioeconomic, cultural and political factors (Norris & Inglehart, 2019; Guriev & Papaioannou, 2020; Rodrik, 2021).

Different varieties of populism operate on different types of grievances and issues across the economic and cultural dimensions of electoral competition, however. Socioeconomic issues have traditionally been identified as critical factors of left-wing populism at both the party and the voter level (Charalambous & Ioannou, 2019) and have become increasingly relevant for right-wing populist parties since the 2008 financial crisis (Ibsen, 2019; Guriev & Papaioannou, 2020; Rodrik, 2021). Immigration has long been identified by research as a critical issue for populist radical right parties, and it is typically associated with authoritarian views of society (Mudde, 2007).

While sharing similar populist attitudes, populist voters diverge when it comes to the host ideologies to which their populism is attached (Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, 2018). Populist radical right voters are primarily concerned with cultural issues of immigration and law and order and show stronger nativist and authoritarian attitudes. Voters on the populist radical left tend to embrace more egalitarian and universalistic values while often supporting a libertarian agenda on social issues. Finally, centrist populist voters exhibit strong anti-establishment attitudes and are primarily characterized by protest voting but do not generally show the nationalist attitudes found in right-wing populism (Ivaldi, 2020; 2021). Such parties in CEE often take an anticorruption stance, making this the focus of their electoral appeal (Haughton, Neudorfer & Zankina, 2024).

As Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos (2020) demonstrated, the effect of these different sets of long-term, structural determinants is also conditioned by short-term political discontent, most notably when populist parties are in opposition. Such short-term factors are particularly relevant to studying populism in European elections. EP elections are generally considered ‘second-order elections’ (Reif & Schmitt, 1980). That is, citizens give more weight to national elections than European ones on a range of different variables: political trust, interest in politics, attachment and complexity of politics. In European elections: (a) voters tend to trust national institutions instead of European ones; (b) they have a stronger connection to their own nation rather than the EU, and; (c) they think that European politics is too difficult to grasp and that domestic issues are more compelling than European ones (Braun, 2021).

Looking at party-level data from all European elections between 1979 and 2019, Ehin and Talving (2021) find that the second-order election model continues to wield significant explanatory power, with lower participation rates in EP elections compared with first-order national elections and incumbency being associated with electoral losses in most EP election years.

Because of the increasing politicization of European integration, however, the viability of the second-order election model has been called into question, reflecting the growing salience and resonance of EU-related issues in mass politics and party competition (Hutter et al., 2016). The recent analysis of EU issue voting in the 2019 EP election by Goldberg et al. (2024) concludes that such issues matter for all EP political groups under scrutiny (both mainstream and more radical), which speaks against the idea of conditional mobilization by Eurosceptic parties.

Moreover, while Ehin and Talving (2021) see the ‘second-order type as constituting a base for a fragmented parliament with a strong representation of populist and extremist parties, other studies, such as Wondreys (2023), find only limited evidence for a boost in electoral support for extreme parties in European elections. This finding is particularly salient when considering the size of those parties and their changing role and status in European party systems. As Wondreys (2023: 7) argues: ‘[G]iven the overall increase in size, the role of many extreme parties in their respective party systems may have changed…. Voters already vote for these parties in [first-order elections], and thus have fewer incentives to subsequently vote for them in [second-order elections] as well.’

At the same time, several European countries held elections at multiple levels concurrently from 7–9 June 2024. These included Belgium, which held federal elections alongside European Parliament elections; Bulgaria, which held another early national parliamentary election on the same date as the EP one; and several countries that held local elections alongside the European ones (i.e., Cyprus, Hungary, Italy, Ireland, Malta and Romania). In these cases, we can expect to see European issues merge, rendered secondary or disappear altogether as domestic issues take precedence.

Looking back at the 2019 EP elections

The 2019 EP elections took place in the wake of the migration crisis shaped by an unprecedented refugee flow to European countries, mainly from the Middle East and Africa, which peaked in 2014–2016. The crisis fed into the populist parties’ Eurosceptic, nativist and nationalist narratives, which were even embraced by mainstream parties (Mudde 2019; Capozzi et al., 2023; Rodi et al., 2023). With the associated cultural sensitivities and economic, social and demographic concerns, European public interest has always been high in the political discourses on migration. In this sense, how the EU managed the refugee influx stood at the heart of discussions between 2015 and 2019. In parallel with Eurosceptic and populist concerns around European integration and migration, the economic agenda remained prominent during the 2019 EP election (Braun & Schafer, 2022). Finally, Brexit remained an important issue, serving as a benchmark of evaluation for citizens to reflect on the benefits of European membership to their own countries (Hobolt et al., 2022). In this regard, debates on the legitimacy of supranational governance, as heightened in the framework of sovereignty, were the most exploited narrative by populists against the EU (Ruzza and Pejovic 2019).

However, the predicted surge in support for populism did not fully materialize in the 2019 EP elections (Ivaldi, 2020). Despite a slowdown of economic activity, the economic context was somewhat less favourable to populist mobilization, as unemployment and inflation remained relatively low across much of Europe. Meanwhile, the impact of the EU migration crisis that had fuelled support for right-wing nationalist populists seemed to wane: economic issues dominated the 2019 European election agenda, together with climate change and promoting human rights and democracy, while immigration ranked fifth (European Parliament, 2019).

Moreover, in a context of high political uncertainty, polls showed more substantial support for the EU across member states. In the Spring 2019 Eurobarometer survey, 61% of EU citizens said that EU membership was good for their country, a figure at its highest since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 (Eurobarometer, 2019). Meanwhile, interest in the election was much higher than in 2014, and voter turnout increased in 20 of the then-28 EU member states, most substantially in countries such as Poland (+22 percentage points), Romania (+19), Spain (+17), Austria (+15), and Hungary (+14).

In the 2019 elections, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) lost their majority for the first time since 1979, securing 182 and 154 seats, respectively. A significant number of voters dissatisfied with Europe’s ruling grand coalition turned to the Greens and Liberals. The Greens won a total of 74 seats, making significant gains in Western European countries such as Germany, France, Ireland and the UK. Pro-EU liberals secured 108 seats, which made Renew Europe the third largest group in the European Parliament.

Meanwhile, populist parties rose to a total of 241 seats, representing about a third (32%) of all 751 seats in the European Parliament at the time, as opposed to 211 seats (28%) five years earlier. However, the election showed mixed performances for populist party families across EU member states.

The outcome essentially confirmed the electoral consolidation of the populist right: together, these parties won 168 seats in 2019 – their best result ever – compared with 131 seats five years earlier. Support for right-wing populist parties significantly rose in Italy, Germany, Spain, Estonia, Sweden and Belgium and they dominated the polls in countries such as France, Italy and the UK. In Italy, Matteo Salvini’s Lega was the big election winner, with 34.3% of the vote compared with only 6.2% in 2014. The National Rally (RN, formerly Front National) topped the polls in France with 23.3% of the vote. In the UK, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party made an impressive breakthrough with 30.5% of the vote, taking over as the main Eurosceptic outfit, a role formerly held by the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP).

In Eastern Europe, ruling conservative parties consolidated electorally: in Poland, Law and Justice (PiS) won 45.4% of the vote, increasing its previous support by 13.6%; in Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz dominated the polls with no less than 52.6%. Smaller, extreme right-wing parties also made gains in Greece and Slovakia. In Greece, Golden Dawn retained two of its previous four seats. In Slovakia, the neo-nazi People’s Party Our Slovakia (L’SNS), headed by Marian Kotleba, won 12.2% of the vote and two seats. In Cyprus, the National Popular Front (ELAM) increased its support to 8.3% (+5.6 percentage points) but failed to secure one of the island’s six seats in the European Parliament.

In contrast, there was a significant drop in support for the populist left, from 43 seats in 2014 to 37 in the 2019 election. Left-wing populist parties had made substantial gains in the wake of the 2008 Great Recession, particularly in countries such as Greece and Spain, hit hardest by austerity policies (see Kriesi & Pappas, 2015: 23). In the 2014 elections, the populist radical left surged in Greece, Spain and Ireland and such parties made significant inroads in Portugal, Italy and France (Hernández & Kriesi, 2016). In 2019, against the backdrop of a timid economic recovery and lower unemployment, these parties lost ground across most EU member states, most notably in countries like Greece, Spain and France. In Eastern and Central Europe, the populist left remained relatively marginal electorally.

Finally, in 2019, centrist populist parties secured 32 of their previous 33 seats. Centrist populists lost momentum in countries of the former Communist bloc, such as Latvia, where Who Owns the State? (KPV) collapsed to less than 1% of the vote, as opposed to their 14.3% showing in the 2018 national elections. In Estonia, the Estonian Centre Party (EK) fell by 8.6%. In the Czech Republic, the governing ANO and its highly controversial leader, Andrej Babiš, took just 21.2% of the vote, down 8.4 percentage points from its previous result. In Bulgaria, electoral support for the ruling GERB fell by 2 percentage points, although Boïko Borissov’s party remained the most potent force in Bulgarian politics with 30.9% of the European election vote. Centrist populist parties also performed badly in Slovakia, Poland, Lithuania and Croatia. In Western Europe, the Five Star Movement (M5S) was the biggest loser of the 2019 Italian EP election, losing 15.6% compared to the 2018 national election.

With a specific reference to Euroscepticism, the 2019 elections were a real success. In almost all member states, except Luxembourg, Malta, Slovenia and Romania, anti-EU movements won seats. The 2019 elections formed a parliament where more than 28% of MEPs belonged to populist or Eurosceptic parties (Treib, 2021: 177).

The context of the 2024 EP elections

The 2024 EP elections were held in a context characterized by the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns about the EU’s handling of migration and refugee issues, the deteriorating economic situation and inflation crisis in member countries, security challenges posed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the newly erupted Israeli–Hamas war in the Middle East.

The EU faced unprecedented challenges due to the COVID-19 crisis and is still dealing with its economic and social consequences. It adopted a €750 billion recovery fund called NextGenerationEU to support member states’ recovery efforts. However, the implementation of this fund was delayed by political disputes and legal challenges, potentially fuelling political discontent – an issue that also carried onto the 2024 EP elections.

Concerning migration and asylum policy reform, the EU has been struggling to find a common approach to address the influx of migrants and asylum seekers, especially from Africa and the Middle East. The current system, based on the Dublin Regulation, has been criticized for putting too much pressure on the frontline states, such as Greece, Italy and Spain and for failing to ensure solidarity and responsibility-sharing among member states. To address this, the European Commission proposed a new pact on migration and asylum to create a more balanced and comprehensive framework for managing migration flows (European Commission, 2024). The proposal took a long time to go through the necessary legislative process due to the opposition from some member states, such as Hungary, Poland and Austria, who rejected mandatory relocation quotas and favoured stricter border controls.

Challenges were not limited to domestic issues; the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a litmus test for the common foreign and security policy of the Union. The EU was confronted with a deteriorating security situation in Eastern Europe as Russia intensified its military aggression against Ukraine and threatened to cut off gas supplies to Europe. The EU imposed sanctions on Russia, but disagreement elicited among the member states on the extent of support and related issues like grain imports from Ukraine. The ECPS report on the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on populism in Europe concluded that populist radical right parties exploited the war as an opportunity to voice their anti-EU rhetoric with sovereigntist arguments. In this vein, their common stance towards the sanctions had been hesitancy and scepticism, illustrating them as not really in line with economic and security-related national interests (Ivaldi & Zankina, 2023).

Furthermore, the recent terrorist attack of Hamas on Israel and the subsequent outbreak of the Israel–Hamas war bore high risks not only for the Middle East but also for other parts of the world, including Europe. Considering the heavy historical and political baggage the Israeli-Palestinian conflict held, it seemed like a convenient topic to be exploited by populist parties ahead of the elections. Instances such as the terrorist attack in Brussels, in which two Swedish citizens were killed in the days after the start of the war, provided room for populists’ rhetoric in the form of xenophobia, Islamophobia and anti-migration.

However, this ‘polycrisis’ was expected to play out differently in each country. The survey by Krastev and Leonard (2024a), which was conducted in September and October 2023 in 11 European countries (Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Switzerland), suggests that the crises of the economy, security, health, climate and migration, have created distinct political responses and opinions across Europe. While immigration was the key issue in Germany, France and Denmark, people in other European countries identified climate change as the most important crisis. Italians and Portuguese, in turn, pointed to global economic turmoil, while in Spain, Great Britain and Romania, the COVID-19 pandemic was the principal issue. Estonians, Poles and Danes considered the war in Ukraine to be the most serious of crises.

In such context, the 2024 European elections represented a crucial test for both the EU and national governments, as voters would evaluate their handling of the pandemic and the recovery and how they planned to address the long-term challenges of climate change, digital transformation, and social cohesion (Bassot, 2023).

However, public opinion data showed relatively positive views toward the Union among EU citizens. Trust in the EU has increased by 6 percentage points since 2019 and now stands at 49%. The perception of the situation of the European economy has improved since autumn 2023, with 47% of respondents rating it as ‘good’, the highest level since 2019. Nearly two-thirds (62%) also said they were optimistic about the future of the EU, which is a slight increase (+4 percentage points) compared to five years earlier. Feelings of being ‘citizens of the EU’ dominated for 74% of the respondents, the highest level in over two decades. Meanwhile, a majority of respondents said they were satisfied with the way democracy works in their country (58%) and in the EU (57%) (Eurobarometer, 2024).

An anticipated rise in support for right-wing populists across the EU

Populist parties have gained traction in recent years, reflecting a broader trend of rising populism across the continent. This surge in popularity has been particularly noticeable among right-leaning populist parties (Ivaldi & Torner, 2023). Such rise in support has been exemplified by the Alternative für Deutschland’s (AfD) triumph in regional elections in eastern states of Germany, the remarkable success of Le Pen’s NR in the 2022 French elections, Giorgia Meloni’s FdI breakthrough in the 2022 Italian election, as well as by the performances of the Sweden Democrats and Finns Party in the last parliamentary elections, which all point to a further increase in the representation of right-wing populist parties in the next EP. In Italy, Meloni’s FdI and Salvini’s Lega, respectively part of the ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists) and Identity and Democracy (ID), were also seen as potentially decisive actors in the alliance formation of the next European Parliament (Massetti, 2023; Maślanka, 2023).

Elsewhere in Europe, right-wing populist parties have become established in countries like Portugal and Spain, and they have topped the polls in Austria and Belgium. In CEE, right-wing populism has been on the rise in Estonia, Croatia, Romania and Bulgaria. In Hungary, Orbán’s Fidesz secured another term in government in the 2022 elections with a clear victory, putting the contested topics between the party and the EU, like the supremacy of the rule of law, immigration, the Russia–Ukraine War, on the agenda of the EP elections. Moreover, Fidezs’s suspension by the EPP and then its departure from this political group has led the party to search for new coalitions after the elections, with talks of joining the ECR group. In Poland, the October 2023 national elections resulted in the opposition parties’ coalition winning over the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) and the new government of pro-EU Prime Minister Donald Tusk. While such an outcome will undoubtedly improve relations between Poland and the EU, PiS has maintained its support at around 30% of the vote, together with Confederation, a heterogeneous extremist group at about 10% of the vote.

Analysts predicted ‘a major shift to the right in many countries, with populist radical right parties gaining votes and seats across the EU and centre-left and green parties losing votes and seats’ (Krastev & Leonard, 2024b). Anti-European populists were expected ‘to top the polls in nine member states (Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Slovakia) and come second or third in a further nine countries (Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden)’ (Ibid.)

The European Parliament and party groups

While reflecting the existing balance of strength across national contexts, populist party performances at the EU level may significantly impact the configuration of party groups within the EP, which is a key legislative body of the EU, working alongside the Council of the European Union to adopt European legislation following proposals by the European Commission. The EP comprises 705 members (MEPs) – 720 in the new EP – making it the second-largest democratic electorate in the world. These MEPs are elected every five years by the citizens of the EU through universal suffrage.

The structure and operation of the EP are governed by its Rules of Procedure, and the political bodies, committees, delegations and political groups guide EP activities. The representation of citizens is ‘degressively proportional’, with a minimum threshold of six members per member state and no member state having more than 96 seats. Degressive proportionality means that while seats are allocated based on the population of the member states, more populous member states agree to be under-represented to favour greater representation of less populated ones.

Political groups within the EP can be formed around a single European political party or can include more than one European party as well as national parties and independents. Prior to the 2024 EP elections, the existing political groups in the EP were the EPP, the Progressive Alliance of S&D, Renew Europe (previously ALDE), the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA), ECR, The Left in the EP (GUE/NGL), and ID.

The outgoing EP was home to both left-wing and right-wing populist parties, that is, while Brothers of Italy (FdI), Vox of Spain, Sweden Democrats, Fidesz of Hungary, Law and Justice (PiS) of Poland, the Finns Party (Perussuomalaiset), the AfD, the National Rally of France, stood on the right side of the spectrum, Podemos of Spain and SYRIZA of Greece represented left-wing populism in the 2019–2024 EP. Regarding political group membership, right-wing populist parties tend to choose different political groups, preventing them from having a common voice in the EP. After the 2019 elections, however, their seeking of collaboration has become more evident, especially under the umbrella of ID and ECR.

Questions addressed in the report

Under the auspices of the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), this report examines the electoral performances and impacts of populist parties in the 2024 European elections. Based on a compilation of country-specific analyses by local experts, the report looks at populist party performances across all EU member states, and it discusses the challenges of populist politics for European institutions as well as for the future of Europe.

Each chapter provides background information about the main populist forces in the country of focus by examining their history, electoral support and political agenda. This includes populist parties across the spectrum where deemed relevant. With a focus on the 2024 European election, each country chapter looks at the ‘supply side’ of populism (i.e., the positions of populist parties towards the EU in general and vis-à-vis specific policies, such as migration and asylum, fiscal policy, the Schengen system, European citizenship and democracy, the COVID-19 pandemic, human rights, as well as external affairs, including policy towards the Russia–Ukraine and Israel–Hamas conflicts). Country analyses ask how populists used Euroscepticism, national sovereignty, ethnic culture, identity, xenophobia and religion during the 2024 EP election campaign and what their discourse was on the composition and working mechanisms of the European Parliament.

Additionally, each chapter examines the ‘demand side’ of populism by looking at how populist parties fared in the elections and which topics played a role in their success or failure. Wherever possible, the country chapters in this report provide public opinion data about critical political issues for populist voters and the characterization of crucial sociodemographics of populist voters across different parties and national contexts.

Finally, each country chapter assesses the impact of populist politics in their respective country and at the EU level (e.g., what kind of populist politics are the elected populist parties going to articulate in the EP and which may be their coalition strategy), allowing for the broader conclusions discussed in this report’s final section.

(*) Gilles Ivaldi is researcher in politics at CEVIPOF and professor at Sciences Po Paris. His research interests include French politics, parties and elections, and the comparative study of populism and the radical right in Europe and the United States. Gilles Ivaldi is the author of De Le Pen à Trump : le défi populiste (Bruxelles: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2019), The 2017 French Presidential Elections. A political Reformation?, 2018, Palgrave MacMillan, with Jocelyn Evans. He has recently co-edited The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe, European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), 2023, with Emilia Zankina. His research has appeared in journals such as Electoral Studies, the International Journal of Forecasting, Revue Européenne des Sciences Sociales, French Politics, Revue Française de Science Politique or Political Research Quarterly.

(**) Emilia Zankina is an Associate Professor in Political Science and interim Vice Provost for Global Engagement at Temple University and, since 2020, has served as the Dean of Temple University Rome. She holds a PhD in International Affairs and a Certificate in Advanced East European Studies from the University of Pittsburgh. Her research examines East European politics, populism, civil service reform, and gender in political representation. She has published in high-ranking international journals, including West European Politics, Politics and Gender, East European Politics, Problems of Post-communism, and Representation, as well as academic presses such as the ECPR Press, Indiana University Press, and others. She frequently serves as an expert adviser for Freedom House, V-Democracy, and projects for the European Commission. In the past, Zankina has served as Provost of the American University in Bulgaria, Associate Director of the Center for Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pittsburgh and Managing Editor of East European Politics and Societies.

References

Bale, T. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (eds) (2021) Riding the Populist Wave. Europe’s Mainstream Right in Crisis, Cambridge University Press.

Bassot, É. (2023). The Six Policy Priorities of the Von der Leyen Commission: State of Play in Autumn 2023. Brussels: European Parliament Research Service, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2023/751445/EPRS_IDA(2023)751445_EN.pdf

Braun D. (2021), The Europeanness of the 2019 European Parliament elections and the mobilising power of European issues, Politics, 41:4, 451–466.

Braun D. & Reinl A. K. (2023), Who holds the union together? Citizens’ preferences for European Union cohesion in challenging times. European Union Politics, 24:2, 390–409.

Braun D. & Schafer C. (2022), Issues that mobilize Europe: the role of key policy issues for voter turnout in the 2019 European Parliament election. European Union Politics, 23:1, 120–140.

Buštíková, L. (2017) The radical right in Eastern Europe. In: J. Rydgren (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right(pp. 565–581), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Capozzi et al. (2023), The Thin Ideology of Populist Advertising on Facebook during the 2019 EU Elections. Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference May 1–5, 2023, Austin, TX, USA, https://doi.org/10.1145/3543507.3583267

Charalambous, G., & Ioannou, G. (Eds.) (2019) Left radicalism and populism in Europe, Routledge studies in radical history and politics. New York: Routledge.

De la Torre, C. (Ed.) (2019). Routledge Handbook of Global Populism, London, Routledge

Ehin P. & Talving L. (2021), Still second-order? European elections in the era of populism, extremism and Euroscepticism. Politics, 41:4, 467–485.

Engler, S., Pytlas, B., & Deegan-Krause, K. (2019) Assessing the diversity of anti-establishment and populist politics in Central and Eastern Europe. West European Politics, 42:6, 1310–1336.

Eurobarometer (2019). Standard Eurobarometer 91–Spring 2019 (European citizenship). Retrieved 4 August 2024 from https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2253

Eurobarometer (2024). Standard Eurobarometer 101–Spring 2024. Retrieved 4 August 2024 from https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3216

European Commission (2024). Pact on Migration and Asylum: A common EU system to manage migration. Retrieved 20 September 2024 from https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/migration-and-asylum/new-pact-migration-and-asylum_en

European Parliament (2019). ‘The 2019 Post-electoral Survey: Have European Elections Entered a New Dimension? Eurobarometer Post-Election Survey 91.5 of the European Parliament, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/

file?deliverableId=74390

FEPS (2024) The transformation of the mainstream right and its impact on (social) democracy, Policy Study, Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS), April.

Goldberg, A. C., van Elsas, E. J., & De Vreese, C. H. (2024). The differential impact of EU attitudes on voting behaviour in the European parliamentary elections 2019. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 1–20.

Gómez-Reino Cachafeiro, M., & Plaza-Colodro, C. (2018). Populist Euroscepticism in Iberian party systems. Politics, 38(3), 344–360.

Guriev, S. & Papaioannou, E. (2020) The Political Economy of Populism, CEPR Discussion Paper DP14433.

Halikiopoulou D. & Vasilopoulou S. (2014), Support for the Far Right in the 2014 European Parliament Elections: A Comparative Perspective. The Political Quarterly, 85:3, 285–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12102

Hanley, S. & Sikk, A. (2016) Economy, corruption or floating voters? Explaining the breakthroughs of anti-establishment reform parties in Eastern Europe. Party Politics 22, 522–533.

Haughton, T., Neudorfer, N., and Zankina, E. (2024). ‘There Are Such People: The Role of Corruption in the 2021 Parliamentary Elections in Bulgaria’, East European Politics, 40:3, 521–546.

Havlík, V. (2019) Technocratic Populism and Political Illiberalism in Central Europe. Problems of Post-Communism, 66:6, 369–384.

Hernández, E. and Kriesi, H-P. (2016). The electoral consequences of the financial and economic crisis in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 55: 203–224.

Hobolt et al. (2022), The Brexit deterrent? How member state exit shapes public support for the European Union. European Union Politics, Vol 23(1), 100–119.

Hutter S., Grande E. & Kriesi H. (Eds.) (2016) Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ibsen, Malte Frøslee. 2019. The Populist Conjuncture: Legitimation Crisis in the Age of Globalized Capitalism. Political Studies 67:3, 795–811.

Ivaldi, G., Lanzone, M.E., Woods, D. (2017). Varieties of Populism Across a Left-Right Spectrum: the case of the Front National, the Northern League, Podemos and Five Star Movement, Swiss Political Science Review, 23:4, 354–376.

Ivaldi, G. (2020) Populist Voting in the 2019 European Elections, Totalitarianism and Democracy, 17:1, 67–96.

Ivaldi, G. (2021). ‘Electoral basis of populist parties’, in R. Heinisch, C. Holtz-Bacha, O. Mazzoleni (eds.) Political Populism. A Handbook, 2nd Edition (pp. 213–224), Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Ivaldi G. & Zankina E. (2023), The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS).

Ivaldi, G. & Torner, A. (2023) From France to Italy, Hungary to Sweden, voting intentions track the far-right’s rise in Europe, The Conversation, 4 October, https://theconversation.com/from-france-to-italy-hungary-to-sweden-voting-intentions-track-the-far-rights-rise-in-europe 20214702

Katsambekis, G. & Kioupkiolis, A. (eds) (2020) The Populist Radical Left in Europe, Routledge

Kneuer, M. (2018). The tandem of populism and Euroscepticism: a comparative perspective in the light of the European crises. Contemporary Social Science, 14:1, 26–42.

Kriesi, H., and S. Pappas, T.S. (Eds.) (2015). European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession, Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

Krastev, I. and Leonard, M. (2024a). A Crisis of One’s Own: The Politics of Trauma in Europe’s Election Year. European Council of Foreign Relations, January 2024. https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/A-crisis-of-ones-own_The-politics-of-trauma-in-Europes-election-year-v2.pdf

Krastev, I. and Leonard, M. (2024b). A New Political Map: Getting the European Parliament Elections Right. European Council of Foreign Relations, March 2024. https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/A-new-political-map-Getting-the-European-Parliament-election-right-v2.pdf

Kriesi H. & Schulte-Cloos J. (2020) Support for radical parties in Western Europe: Structural conflicts and political dynamics. Electoral Studies 65, 102138

Lisi, M., Llamazares, I., Tsakatika, M. (2019) Economic crisis and the variety of populist responses. Evidence from Greece, Portugal and Spain. West European Politics, 42:6, 1284–1309.

Mach E. M. (2023), Right-wing populism, Euroscepticism and neo-traditionalism in Central and Eastern Europe., (IN) The Right-Wing Critique of Europe. Nationalist, Sovereignist and Right-Wing Populist Attitudes to the EU. Routledge, London.

McMahon, R. (2021) Is Alt-Europe possible? Populist radical right counternarratives of European integration. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 30(1), 10–25.

Maślanka L. (2023), Realism or Radicalisation: Meloni Walks Fine Line on European Policy. PISM Bulletin, No. 39 (2158).

Massetti E. (2023), From Europhilia to Eurorealism: The 2022 General Election in Italy. Journal of Common Market Studies, pp. 1–12.

McDonnell D. & Werner A. (2020), International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament., Oxford University Press.

Meijers, M. J., & Zaslove, A. (2021). Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach. Comparative Political Studies, 54(2), 372–407, https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020938081

Moffit, B. (2017) The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style and Representation, Stanford, Stanford University Press.

Mosca, L. & Tronconi, F. (2019) Beyond left and right. The eclectic populism of the Five Star Movement, West European Politics, 42:6, 1258–1283.

Mudde, C. (2007) Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe, Cambridge.

Mudde C. (2019), The 2019 EU elections: moving the center, Journal of Democracy 30:4, 20–34.

Mudde, C. and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018) Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda. Comparative Political Studies, 51:13, 1667–1693.

Muldoon, J. & Herman, L.E. (Eds) (2018) Trumping the Mainstream: The Conquest of Democratic Politics by the Populist Radical Right, London: Routledge.

Munoz A. & Ripollés C. (2020), Populism Against Europe in Social Media: The Eurosceptic Discourse on Twitter in Spain, Italy, France and the United Kingdom during the Campaign of the 2019 European Parliament election. Frontiers in Communication, 5:54, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00054

Norris, P. & Inglehart, R. (2019) Cultural backlash. Trump, Brexit and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olivas Osuna, J.J. (2021), From chasing populists to deconstructing populism: A new multidimensional approach to understanding and comparing populism. European Journal of Political Research, 60: 829–853.

Pirro, A. L., Taggart, P., & van Kessel, S. (2018). The populist politics of Euroscepticism in times of crisis: Comparative conclusions. Politics, 38:3, 378–390, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395718784704

Pirro, A. L. & van Kessel, S. (2018) Populist Eurosceptic trajectories in Italy and the Netherlands during the European crises. Politics, 38:3, 327–343.

Reif, K. & Schmitt, H. (1980), Nine second-order national elections – a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results. European Journal of Political Research, 8: 3–44.

Rodi P., Karavasilis L. & Puleo L. (2023), When nationalism meets populism: examining right-wing populist & nationalist discourses in the 2014 & 2019 European parliamentary elections. European Politics and Society, 24:2, 284–302.

Rodrik, D. (2021) Why Does Globalization Fuel Populism? Economics, Culture and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism. Annual Review of Economics 13:133–170.

Rooduijn, M., Pirro, ALP, Halikiopoulou D., et al. (2023). The PopuList: A Database of Populist, Far-Left, and Far-Right Parties Using Expert-Informed Qualitative Comparative Classification (EiQCC). British Journal of Political Science. Published online 2023:1–10. doi:10.1017/S0007123423000431

Ruzza, C. & Pejovic, M. (2021), Populism at work: the language of the Brexiteers and the European Union. In: F. Zappettini, M Krzyżanowski (Eds.),‘Brexit’ as a Social and Political Crisis: Discourses in Media and Politics (pp. 432–448), Routledge, London.

Schwörer, J. (2021) The Growth of Populism in the Political Mainstream. The Contagion Effect of Populist Messages on Mainstream Parties’ Communicatio, Cham, Springer.

Szczerbiak A & Taggart P. (2024). Euroscepticism and anti-establishment parties in Europe. Journal of European Integration, DOI: 10.1080/07036337.2024.2329634

Taggart, P., & Pirro, A. L. P. (2021). European populism before the pandemic: ideology, Euroscepticism, electoral performance and government participation of 63 parties in 30 countries. Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica, 51:3, 281–304.

Treib O. (2021). Euroscepticism is here to stay: what cleavage theory can teach us about the 2019 European Parliament elections. Journal of European Public Policy, 28:2, 174–189.

Učeň, P. (2007). Parties, Populism and Anti-Establishment Politics in East Central Europe. The SAIS Review of International Affairs, 27(1), 49–62.

Van Hauwaert, S.M. & Van Kessel, S. (2018). Beyond protest and discontent: A cross-national analysis of the effect of populist attitudes and issue positions on populist party support. European Journal of Political Research, 57: 68–92.

Van Kessel, S., Chelotti, N., Drake, H., Roch, J., & Rodi, P. (2020). Eager to leave? Populist radical right parties’ responses to the UK’s Brexit vote. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(1), 65–84.

Wondreys, J. (2023) Unpacking second-order elections theory: The effects of ideological extremity on voting in European elections, Electoral Studies, 85, 102663, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2023.102663

Table 1 illustrates the diversity of populism. Overall, there were about 90 populist parties across all EU member states on the eve of the 2024 European election, with varying ideological profiles, backgrounds and electoral sizes. Essentially, populism was found both left and right of the European political spectrum, as well as at its centre, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

Table 1 illustrates the diversity of populism. Overall, there were about 90 populist parties across all EU member states on the eve of the 2024 European election, with varying ideological profiles, backgrounds and electoral sizes. Essentially, populism was found both left and right of the European political spectrum, as well as at its centre, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).