Marine Le Pen’s conviction for embezzling EU funds might have marked a legal defeat—but politically, it became a narrative victory. In her commentary, Julie Van Elslander explores how France’s far-right leader transformed her trial into a populist spectacle of persecution, mobilizing public anger and institutional distrust. By reframing judicial accountability as elite conspiracy, Le Pen advanced a post-truth strategy that defied factual condemnation and resonated deeply with disillusioned voters. This timely analysis illuminates the broader phenomenon of populist resilience in the face of scandal, showing how legal consequences can be strategically repurposed as political capital by populist actors within Europe’s increasingly contested democratic landscape.

By Julie Van Elslander*

Introduction

On March 31, 2025, Marine Le Pen, long-time leader of France’s far-right National Rally, was convicted by the criminal court of Paris for the misappropriation of an estimated €4.6 million in European Parliament funds (Ledroit, 2025). Sentenced to a heavy condemnation, Marine Le Pen suffered a significant legal and political blow. Yet, instead of weakening her influence or undermining her party’s credibility, the trial became a platform for Le Pen to reaffirm her political narrative. Despite legal conviction and moral discredit, the National Rally maintained political relevance by reframing the sentence as an element of political persecution – raising a question: How does a legal defeat become a populist narrative victory?

At the core, this narrative dynamic is emblematic of what scholars qualify of post-truth populism: The transformation of political culture by the devaluation of factual correctness over emotional appeal (Conrad & Hálfdanarson, 2023). In a context where public discourse is increasingly shaped by the logic of “alternative facts” – a concept introduced by Trump’s counselor in 2017 (Gajanan, 2017) – Le Pen’s trial is another example of the way post-truth populists challenge liberal democracies.

Rather than interrogating the legal dimensions of guilt or innocence, this analysis focuses on the populist discursive strategies through which Marine Le Pen’s trial was reframed in the public sphere, and how those shaped citizens’ political thinking (Aslanidis, 2016). The trial serves not simply as a juridical event, but also as a communicative site where competing narratives about power, legitimacy and truth are constructed.

The Case of Le Pen’s Trial – Facts and Only Facts

Among twenty-four others, nine ex-MEPs and twelve parliamentary assistants from the National Rally were trialed for “embezzlement of public funds” and “complicity in the embezzlement of public funds” from 2004 to 2016 (Maad, 2025). In this case, the court recognized that the European Parliament’s public funds were misappropriated in order to remunerate employees working for the party management under fictitious contracts, rather than related to the European parliamentary activity – as it is normally required for those collaborators (ibid.).

Marine Le Pen was sentenced to a €100.000 fine, two years under house arrest while wearing an electronic ankle bracelet, additional two-year suspended sentence, and five years’ ineligibility for public office with immediate effect. Le Pen’s heavy condemnation was due to what the court’s president as qualified as her “central role” in this case: “at the heart of this system since 2009, Marine Le Pen has signed up with authority and determination in the operation established by her father, in which was participating since 2004” (Dao, 2025).

Le Pen will appeal the verdict, but she will remain ineligible and could be ruled out of the 2027 presidential elections. She won’t serve the house arrest until every appeal is exhausted but the ban on running for office will be implemented immediately despite her legal challenge.

The irony of the case is striking: Marine Le Pen, who used to call for life ineligibility for elected officials convicted of embezzlement or corruption (Brault, 2025), now contests the legitimacy of her own sentence – but how does such a reversal become not a source of discredit, but a tool for reaffirming political legitimacy?

Not Guilty, Just Targeted? Le Pen’s Populist Response to Conviction

Despite her conviction, Marine Le Pen managed to maintain her political standing by discursively reframing the charges into a populist narrative of persecution and resistance. Ever since the trial’s deliberation, Le Pen has not stopped claiming her innocence, repeatedly insisting the judges were “mistaken” and reducing the issue to a simple “administrative disagreement with the European Parliament” that involved “no personal enrichment” (Marchal, 2025). Yet, the tribunal clearly stated that although the actions did not generate direct personal enrichment, they constituted serious breach of integrity and democratic principles, involving deception of both the European Parliament and voters (Sicard, 2025). By providing financial benefits to the National Rally, the stolen funds allowed it to maintain political influence and electoral advantages for over a decade (ibid.).

The judges justified the use of the ineligibility sentence and its exécution provisoire (which allows the sentence to be enforced even before an appeal), emphasizing that the defendants had expressed no recognition of their violation of the law, and the court had a duty to ensure that “elected officials, like any other subject, do not benefit from a preferential regime incompatible with the trust sought by citizens in political life” (France info, 2025). In 2023 alone, around 16.000 ineligibility sentences were issued in France, 639 of which included the exécution provisoire (France info, 2025a). While such measure is applied selectively – and in about 4% of the cases – it is far from exceptional (ibid.). Indeed, several other high-profile political figures in France, such as Nicolas Sarkozy or François Fillon, have been sentenced to ineligibility in recent years (Louis, 2025).

However, in the populist narrative, these precedents are rarely acknowledged. By using terms such as a “tyranny of the judges” (Cossard, 2025), the National Rally reinforced the idea that Le Pen is being unfairly targeted. The rhetoric implies an extraordinary sanction used to silence political opposition: the trial isn’t presented as a neutral legal process, but as the proof of a biased system – with Le Pen denouncing a “political decision,” a practice “we believed to be reserved for authoritarian regimes” (Vignal, 2025). The judiciary becomes just another part of the “elite” that is supposedly trying to stop her from acceding to the Elysée: “the system has released the nuclear bomb. If it uses such a powerful weapon against us, it is obviously because we are about to win the elections” (A.B., 2025). Here, Le Pen’s reframing does not deny the factual events themselves; rather, she strategically reinterprets them because openly acknowledging illegality could undermine her political legitimacy and moral authority.

This discursive approach fits neatly into what researchers call post-truth populism: The idea isn’t just to reject facts but to question who gets to decide what’s true in the first place (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). Populist leaders like Le Pen challenge the credibility and intentions of traditional fact-producers – such as judges, journalists or experts – to position themselves as more trustworthy (Mahmutović & Lovec, 2024). By stating that their version of facts are biased, corrupt or politically motivated, populist leaders construct alternative narratives, in which facts are selectively reinterpreted in ways that support their political agenda. The aim is not necessarily to prove their narrative is objectively true, but rather to undermine opposing ones as suspicious and irrelevant.

This type of rhetoric fits within a common populist logic, where courts and other oversight bodies are seen as tools of an unaccountable elite trying to undermine the will of the “real people” – a homogeneous group not defined by citizenship, but by symbolic alignment with the populist cause (Arato, 2017). By framing her conviction as political persecution, Le Pen not only shields herself from public blame, but also primes her supporters to view the case as of a “stolen election”.

Why Marine Le Pen Wasn’t ‘Cancelled’: Political Loyalty in a ‘Stolen’ Election

Marine Le Pen may have been convicted in court, but in the arena of public opinion, she proved to be remarkably cancel-proof. This resilience is rooted in the post-truth populist strategy that places narrative above norms, and emotional appeal above factual truth. It particularly stemmed among her supporters, for whom the verdict was seen as a symbol of political persecution, and an attempt to steal the 2027 election – a narrative that quickly found concrete expression in public reactions. On March 31, 2025, a few hours after Le Pen’s conviction, a French national news broadcast captured street interviews where multiple citizens reacted with shock and outrage, describing the verdict as “personal” and a way to “take her out” of the presidential race (TF1info, 2025).

An online petition launched by National Rally, titled “Save democracy, save Marine” (Rassemblement National, 2025) rapidly gathered thousands of signatures and rallied support over social media, but its message was not just about supporting Le Pen – it was about defending her voters’ rights. In an open letter promoting the petition, Jordan Bardella, the young president of the National Rally, described the conviction as an attack against voters: “They are trying to prevent a candidacy supported by millions of French people, which is well ahead in all the polls. They deprive millions of voters of their choice and therefore their freedom” (Krupa, 2025). This sense of disenfranchisement was further amplified at a public rally held a week later, during which Bardella addressed the crowd and further defended Le Pen as a candidate of the people, framing her conviction as an attempt to prevent the National Rally from acceding to power (ibid.). The conviction, as he claimed, was not just about her but about the right of French voters to choose their leader. The rally became a platform where Le Pen was portrayed not only as a victim but as a representative of silenced voters.

This narrative fits the typical populist discourse, which emerges from a perceived failure of representation (Rosanvallon, 2020) and frames political reality as a fundamental conflict between a corrupted elite and the common people, “whose mobilization is presented as the only solution” (Aslanidis, 2016) to regain sovereignty. Here, the mobilization efforts are largely symbolic: Neither a petition nor public rally could change the judicial outcome, as courts are not influenced by popularity. However, their aim is to reinforce the idea that the verdict is unjust, judicial independence compromised and that the electors are the true victims of this case. Those efforts function as political and social tools – not legal ones – allowing Le Pen’s supporters to transform outrage into collective action, and to signal strength and solidarity.

This is a key aspect of post-truth populism: The National Rally’s version of events is framed as more authentic because it taps into a deeper, widespread sense of institutional distrust (Harsin, 2024). When ordinary citizens feel that traditional institutions no longer represent them fairly, populist leaders like Le Pen often claim to embody the will of the people directly, calling for diverse forms of direct democracy (ibid.). Within this logic, portraying Le Pen’s sentence as exceptional and biased doesn’t require evidence – it simply needs to fit the broader story that her supporters believe: That she, like them, is being unfairly treated by a system that no longer serves them.

Yet, while this narrative mobilized Le Pen’s supporters within France, the impact of her conviction also reverberated beyond national borders, sparking polarized reactions at the European level.

A European Issue with Global Repercussions

With the National Rally’s discourse focusing on national stakes, the European legal affair was reframed as a national political issue. That is, in part, due to the nature of the European Union’s legal proceedings. Even though the European Parliament’s public funds are distributed through the institutions, MEPs are elected nationally and therefore reside within national jurisdiction. The investigation was first opened by the OLAF – the European Anti-Fraud Office, an independent entity – in 2014 (Bouquet, 2025), but criminal prosecution and sentencing remained the responsibility of national courts. Although the matter originated at the European level, with the European Parliament lifting Le Pen’s immunity following a referral to French authorities, the fact that the trial was handled nationally contributed to the widespread perception that it was a purely domestic affair. This procedural pathway ultimately placed the case within a broader discursive shift, reframing the trial as a French political controversy – judges, media and legal discourse – all nationally situated.

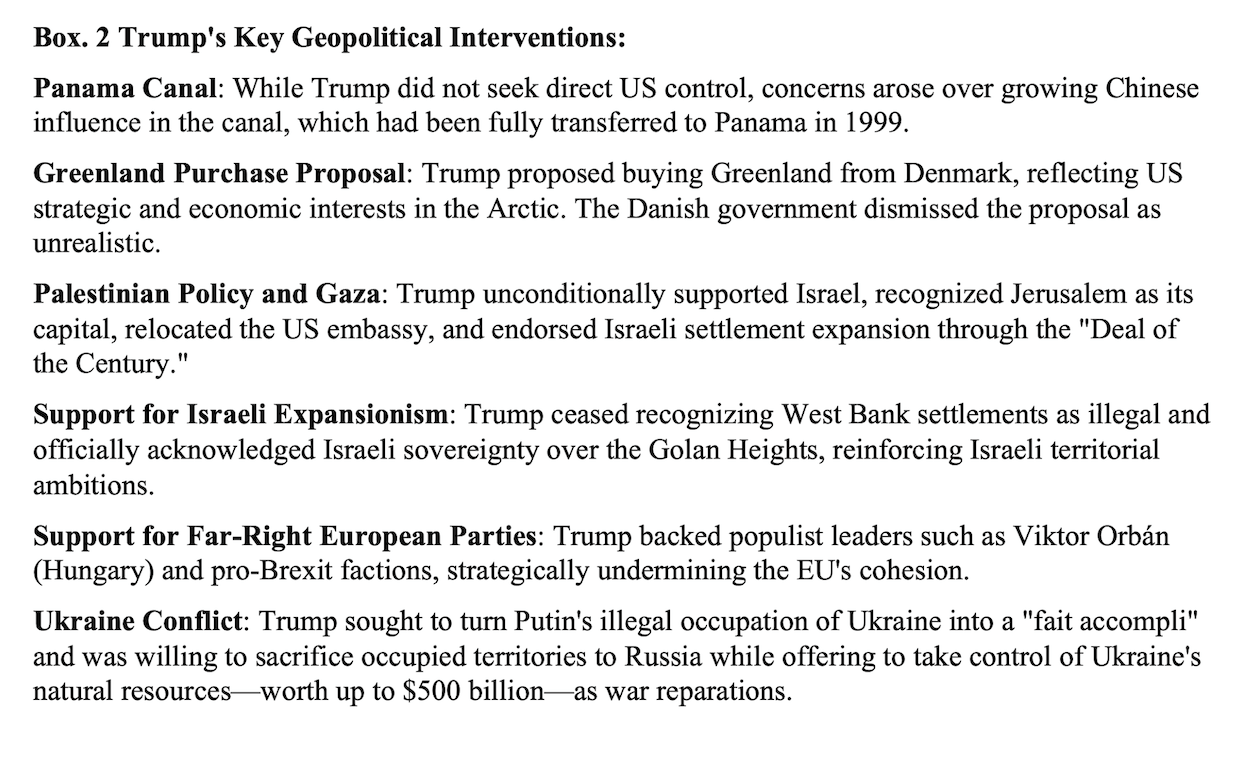

Moreover, the French discourse largely undermined the collective European harm caused by the embezzlement. While the European Parliament – the civil plaintiff in the case – announced it “took note” of the decision and declined to comment further, Le Pen’s conviction quickly gathered support among fellow populist leaders, particularly from far-right figure such as Viktor Orbán, Matteo Salvini, and Donald Trump. Orbán expressed direct solidarity by stating “Je suis Marine!” – a phrase typically used to express support and mourning for victims – while Salvini denounced the verdict as a “declaration of war by Brussels” (Les Echos, 2025). Trump compared Le Pen’s legal troubles to his own, labeling it a “witch hunt” and accusing European elites of using the judiciary to silence political opposition (Le Monde, 2025).

These international endorsements were not merely supportive gesture; they became central elements of the populist narrative surrounding Le Pen’s case. While the trial was framed in France as a part of a broader struggle between national sovereignty and a hostile elite, this international support further cast her as a symbol of resistance against a corrupt system – reinforcing the idea of a national and European political conspiracy targeting her.

The same divisive framing extended into the European Parliament itself. During the plenary session held shortly after the verdict, several Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) from the Patriots for Europe group – Le Pen’s European political family – expressed their support for Le Pen, condemning the conviction as undemocratic and broadly questioning the state of the rule of law in Europe. Hungarian MEP András László notably accused the “Brussels elite” of trying to “legally sabotage a far-right politician” because of her patriotism and opposition to a “globalist elite” (European Parliament, 2025) – aligning with the narrative of persecution. In contrast, MEPs from other political groups welcomed the conviction as a critical step in combating corruption within the institution. German MEP Daniel Freund notably qualified the Le Pen’s actions as “the biggest fraud case in the history of the European Parliament” (ibid.).

This polarized reaction within the European Parliament highlighted the trial’s dual nature: Legally, it was a case of embezzlement involving European funds, but politically, it became a battleground over competing narratives. For Le Pen’s allies, it symbolized a struggle against an oppressive European elite; for her critics, it was a long-overdue act of accountability.

Indeed, Le Pen’s case comes within the broader context of corruption scandals that have been shaking the European Parliament itself. The Qatargate scandal in 2022, involving allegations of bribes paid by Qatar to influence European lawmakers, and the Huawei case in 2023, where Chinese lobbying was accused of seeking favorable policies through financial incentives, exposed the vulnerability of European institutions to corruption. These scandals not only undermined the Parliament’s authority as a democratic institution of EU decision-making but also deepened the citizens’ distrust in EU governance – a distrust that populists are quick to weaponize.

Conclusion

The Le Pen case is more than a legal scandal – it is a test of the resilience of European institutions against populist narratives that thrive on distrust. It is not merely about one politician reframing her conviction as persecution; it is a case study in how a legal process can be transformed into a battleground of competing truths. At its core, this case reveals a deeper conflict between factual accountability and symbolic politics.

Ultimately, the stakes go beyond Le Pen herself. The crisis of trust she has exploited is part of a broader European problem. As Qatargate and the Huawei scandal have shown, European institutions are not immune to corruption, and this vulnerability has fueled perceptions of institutional hypocrisy. It is this perceived hypocrisy that populist leaders weaponize, transforming legitimate accountability efforts into narratives of persecution. Ultimately, the Le Pen case is a message of political legitimacy: In an era of post-truth populism, the verdict in court may matter less than the verdict in public opinion.

(*) Julie Van Elslander is a double master’s student in European Governance (Sciences Po Grenoble) and Politics and Public Administration (Universität Konstanz), with a strong interest in how democracies respond to challenges like populism, post-truth politics, and institutional distrust. She has contributed to European-level research projects on political communication, corruption, and democratic accountability, and currently works as a research intern at the Center of International Relations (University of Ljubljana).

References

A.B. (2025, April 1). » Condamnation de Marine Le Pen : “Le système a sorti la bombe nucléaire,” affirme la cheffe des députés RN. » TF1 INFO. https://www.tf1info.fr/politique/condamnation-de-marine-le-pen-discours-le-systeme-a-sorti-la-bombe-nucleaire-affirme-la-cheffe-des-deputes-rn-2362610.html

Arato, A. (2017, April 25). Populism and the courts. Verfassungsblog. https://verfassungsblog.de/populism-and-the-courts/ https://doi.org/10.17176/20170425-082356

Aslanidis, P. (2016). “Is Populism an Ideology? A Refutation and a New Perspective.” Political Studies, 64(1_suppl), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12224

Bouquet, J. (2025, April 3). « Affaire des assistants parlementaires du RN : retour sur dix ans d’une procédure qui pourrait arrêter Marine Le Pen aux portes du pouvoir. » RTBF Actus. RTBF. https://www.rtbf.be/article/affaire-des-assistants-parlementaires-du-rn-retour-sur-dix-ans-d-une-procedure-qui-pourrait-arreter-marine-le-pen-aux-portes-du-pouvoir-11525787

Brault, P. (2025, April 2). « Sur l’inéligibilité à vie, Marine Le Pen ne voit pas de « contradiction » avec ses déclarations de 2013. » Le HuffPost. https://www.huffingtonpost.fr/politique/article/sur-l-ineligibilite-a-vie-marine-le-pen-ne-voit-pas-de-contradiction-avec-ses-declarations-de-2013_248263.html

Conrad, M., & Hálfdanarson, G. (2023). “Introduction: Europe in the Age of Post-Truth Politics.” In: M. Conrad, G. Hálfdanarson, A. Michailidou, C. Galpin, & N. Pyrhönen (Eds.), Europe in the Age of Post-Truth Politics (pp. 1–9). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13694-8_1

Cossard, L. (2025, April 1). « VRAI OU FAUX. Marine Le Pen inéligible : les juges ont-ils vraiment rendu une “décision politique”, comme le clame le RN ? » Ladepeche.fr. https://www.ladepeche.fr/2025/04/01/vrai-ou-faux-marine-le-pen-ineligible-les-juges-ont-ils-vraiment-rendu-une-decision-politique-comme-le-clame-le-rn-12608018.php

Dao, L. (2025, April 4). « VRAI OU FAUX. Détournement de fonds publics : peut-on comparer la condamnation de Marine Le Pen et la relaxe de François Bayrou. » Franceinfo. https://www.francetvinfo.fr/vrai-ou-fake/vrai-ou-faux-detournement-de-fonds-publics-peut-on-comparer-la-condamnation-de-marine-le-pen-et-la-relaxe-de-francois-bayrou_7164336.html#comments-embed

European Parliament (2025). Sitting of 31-03-2025 | Plenary | European Parliament. © European Union, 2016 – Source: European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/plenary/en/vod.html?mode=chapter&vodLanguage=EN&internalEPId=2017020025473&providerMeetingId=20250331-0900-PLENARY#

Franceinfo (2025, April 1). Condamnation de Marine Le Pen : comment le tribunal correctionnel de Paris a-t-il justifié son jugement ? https://www.francetvinfo.fr/politique/front-national/affaire-des-assistants-fn-au-parlement-europeen/condamnation-de-marine-le-pen-comment-le-tribunal-correctionnel-de-paris-a-t-il-justifie-son-jugement_7164255.html

France Info (2025a, April 3). Inéligibilité de Marine Le Pen : l’exécution provisoire est-elle une décision rare de la justice ? https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceinfo/podcasts/le-vrai-ou-faux/ineligibilite-de-marine-le-pen-l-execution-provisoire-est-elle-une-decision-rare-de-la-justice-1740119

Gajanan, M. (2017, January 22). Kellyanne Conway defends White House’s falsehoods as ‘Alternative facts.’ TIME. https://time.com/4642689/kellyanne-conway-sean-spicer-donald-trump-alternative-facts/

Harsin, J. (2024). Post-truth Politics and Epistemic Populism: About (Dis-)Trusted Presentation and Communication of Facts, Not False Information. In Newman, S., Conrad, M. (eds) Post-Truth Populism. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64178-7_2

Krupa, J. (2025, March 31). “National Rally president calls for ‘peaceful mobilisation’ after Marine Le Pen convicted of embezzlement – as it happened.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2025/mar/31/france-marine-le-pen-embezzlement-verdict-europe-news-live

Ledroit, V. (2025, March 31). « Affaire des assistants du FN au Parlement européen : Marine Le Pen condamnée à quatre ans de prison, dont deux ferme, et cinq années d’inéligibilité . » Touteleurope.eu. https://www.touteleurope.eu/institutions/affaire-des-assistants-du-fn-au-parlement-europeen-marine-le-pen-condamnee-a-quatre-ans-de-prison-dont-deux-fermes-et-cinq-annees-d-ineligibilite/

Le Monde. (2025, April 7). « Marine Le Pen’s Trumpian temptation. » https://www.lemonde.fr/en/opinion/article/2025/04/07/marine-le-pen-s-trumpian-temptation_6739921_23.html

Les Echos. (2025, April 1). « Trump juge «très grave» l’inéligibilité de Le Pen et compare cette condamnation à ses propres affaires judiciaires. » https://www.lesechos.fr/politique-societe/politique/ineligibilite-de-marine-le-pen-poutine-et-orban-soutiennent-la-patronne-du-rn-2157128

Louis, A. (2025, April 1). « Condamnation de Marine Le Pen : Sarkozy, Balkany, Cahuzac. . . avant la cheffe du RN, ces politiques sous bracelet électronique. » Libération. https://www.liberation.fr/politique/condamnation-de-marine-le-pen-sarkozy-balkany-cahuzac-avant-la-cheffe-du-rn-ces-politiques-sous-bracelet-electronique-20250401_NKLGPIFGLRHWZCT3GP56S6F2F4/

Maad, A. (2025, April 1). « Marine Le Pen condamnée dans l’affaire des assistants parlementaires du FN : ce que la justice lui reproche. » Le Monde.fr. https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2025/03/31/marine-le pen-condamnee-dans-l-affaire-des-assistants-parlementaires-du-fn-ce-que-la-justice-lui-reproche_6588582_4355771.html

Mahmutović, M., & Lovec, M. (2024). “‘The First in the Service of Truth’: Construction of Counterknowledge Claims and the Case of Janša’s SDS’ Media Outlets.” In: S. Newman & M. Conrad (Eds.), Post-Truth Populism (pp. 177–216). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64178-7_7

Marchal, R. (2025, March 31). « Inéligibilité : Marine Le Pen fustige une “décision politique” de la justice et confirme qu’elle va faire appel de sa condamnation. » LCP – Assemblée Nationale. https://lcp.fr/actualites/ineligibilite-marine-le-pen-fustige-une-decision-politique-de-la-justice-et-confirme-qu

Rassemblement National (2025). Sauvons la démocratie, soutenons Marine !https://rassemblementnational.fr/petition/defendez-la-democratie-soutenez-marine

Rosanvallon, P. (2020). Le Siècle du populisme. Histoire, théorie, critique. Média Diffusion.

Sicard, S. (2025, April 7). « Inéligibilité de Marine Le Pen : “Il n’y a pas eu d’enrichissement personnel…” La justice moins catégorique sur l’affirmation répétée par le RN depuis l’annonce du jugement. » lindependant.fr. https://www.lindependant.fr/2025/04/07/ineligibilite-de-marine-le-pen-il-ny-a-pas-eu-denrichissement-personnel-la-justice-moins-categorique-sur-laffirmation-repetee-par-le-rn-depuis-12621458.php

TF1info. (2025, March 31). « Marine Le Pen inéligible : “Démocratie exécutée”, “justiciable comme les autres”. . . les réactions divisées de la classe politique. » TF1 INFO. https://www.tf1info.fr/politique/marine-le-pen-ineligible-democratie-executee-justiciable-comme-les-autres-les-reactions-divisees-de-la-classe-politique-2362454.html

Vignal, F. (2025, March 31). « « Soyons bien clairs, je suis éliminée » : Marine Le Pen dénonce une « décision politique » après sa condamnation. » Public Sénat. https://www.publicsenat.fr/actualites/politique/soyons-bien-clairs-je-suis-eliminee-marine-le-pen-denonce-une-decision-politique-apres-sa-condamnation

Ylä-Anttila, T. (2018). Populist knowledge: “Post-truth’ repertoires of contesting epistemic authorities.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 5(4), 356–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2017.1414620