Please cite as:

Petsinis, Vassilis. (2024). “Between ‘Kingmakers’ and Public Indifference: Croatia’s National Conservative Right in the European Elections of 2024.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0064

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON CROATIA

Abstract

This chapter focuses on Croatia and deals with the national conservative Domovinski Pokret/Homeland Movement (DP) party. In the latest European elections, the DP garnered a percentage of 8.82% (65,383 votes and one seat), taking third spot after the ruling (centre-right) Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) and the ‘Rivers of Justice’ coalition spearheaded by the (centre-left) Social Democrat Party (SDP). I begin the present chapter by sketching a typology of the constituent segments along the broad spectrum of the European right wing and situate the DP within it. I then offer a summary of the DP’s founding principles vis-à-vis further European integration and clarify the extent to which these principles were reflected in the party’s stances and active engagement in the latest European elections. I then identify the main catalysts behind the DP leadership’s success in mobilizing target groups and galvanizing electoral support for the party.

Keywords: Radical Right, National Conservatives, European Elections, Euroscepticism, Croatia, Ukraine

By Vassilis Petsinis* (Institute of Global Studies, Corvinus University of Budapest)

Introduction

The results of the European elections (6–9 June 2024) have generated diverse political repercussions on the national, European and global levels. On the one hand, the parties of the centre-right, grouped under the European People’s Party (EPP), and the parties of the centre-left, rallying behind the banner of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) group, succeeded in maintaining the top and the second spot, respectively, at the European level. On the other hand, the landscape became hazier concerning the political forces clustered along the broader right-wing spectrum beyond the EPP – namely, the parties of the national conservative as well as the populist and radical right in the European Parliament (EP).

One catalyst that has complicated the precise assessment of those parties’ performance is that the political forces beyond the conservative centre-right were scattered among different coalitions such as the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID) groups – also including powerful non-attached (NA) political actors including Hungary’s Fidesz party. Nevertheless, it appears that these parties succeeded in one of three ways in the latest European elections. First, some consolidated their already preeminent positions in the domestic politics of their respective states, such as the National Rally (RN) in France, or enhanced their positions significantly, as in the case of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) in Germany, the Freedom Party (PVV) in the Netherlands, and the Law and Justice party (PiS) in Poland. A second set expanded and augmented, to varying degrees, their public appeal, including Vox in Spain, Chega in Portugal, and the Hellenic Solution (EL) in Greece. A third, smaller group saw their support erode due to the emergence of new contenders, most notably the ruling Fidesz party in Hungary, which has ceded popularity to the centre-right Respect and Freedom party (Tisza).

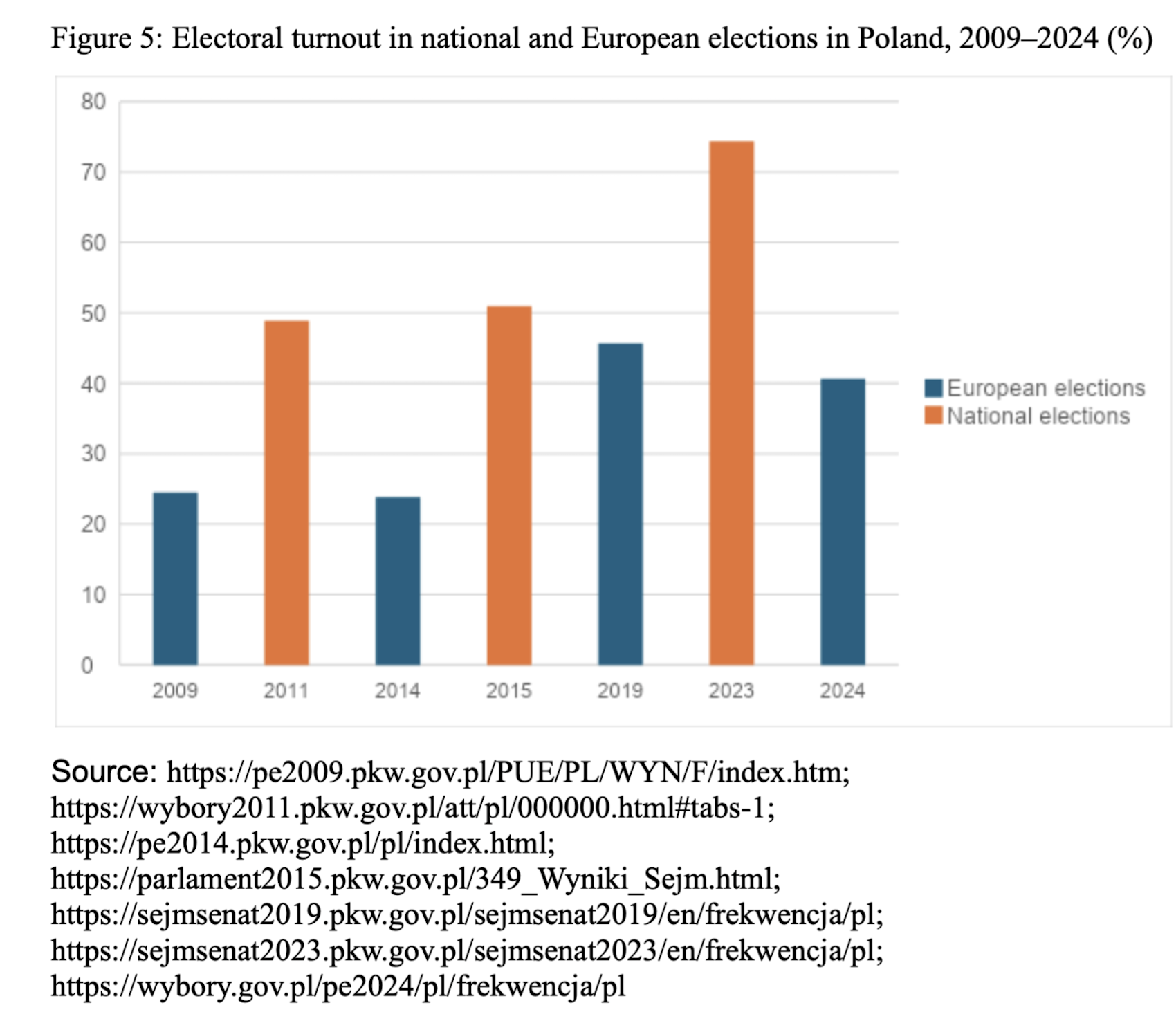

In Central and Southeast Europe, the voter turnout in the latest European elections ranged from relatively high (e.g., Hungary, 59.46%) to relatively low (e.g., Poland, 40.65%; Slovakia, 34.38%) and meagre (e.g., Lithuania, 28.35%) (European Parliament, n.d.). This article casts its lens on Croatia, one of the new member states where the turnout rate was the lowest in the EU (21.35%) (Ibid).

Despite the lack of voter interest, the EU is a significant benefactor for Croatia, which has been heavily dependent on financial support from Brussels since it joined the Union in 2013. In particular, the EU’s Structural and Cohesion Funds have been of crucial significance in upgrading the local infrastructure in the less-developed regions of the country (e.g., certain parts of Eastern Slavonia and Dalmatia). Moreover, especially following the country’s accession to the Schengen Area (1 January 2023), employment opportunities within the EU have provided both ‘white collar’ and ‘blue collar’ professional categories with a vital ‘lifeline’. As an aggregate of these sociopolitical realities, the primary concerns and expectations of the Croatian electorate during the latest European elections predominantly revolved around the economy, and public Euroscepticism was not noticeably high. At the same time, global and regional crises generated shockwaves within the Croatian public and among the country’s political elites. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 is a particular case in point, with several political actors across the political divide seeking to draw tentative analogies between this weighty geopolitical moment and Croatia’s Domovinski Rat (‘Homeland War’) from 1991 to 1995.

As a consequence of the Domovinski Rat, Croatia has several parties that oscillate between the categories of the radical and the extreme right. While formed between the early 1990s and the early 2000s, these parties – including the Croatian Party of Rights (HSP), the Croatian Pure Party of Rights (HČSP) and the Autochthonous Party of Rights (A–HSP) – tend to claim roots in the same nineteenth-century nationalist Hrvatska Stranka Prava or Croatian Party of Rights.

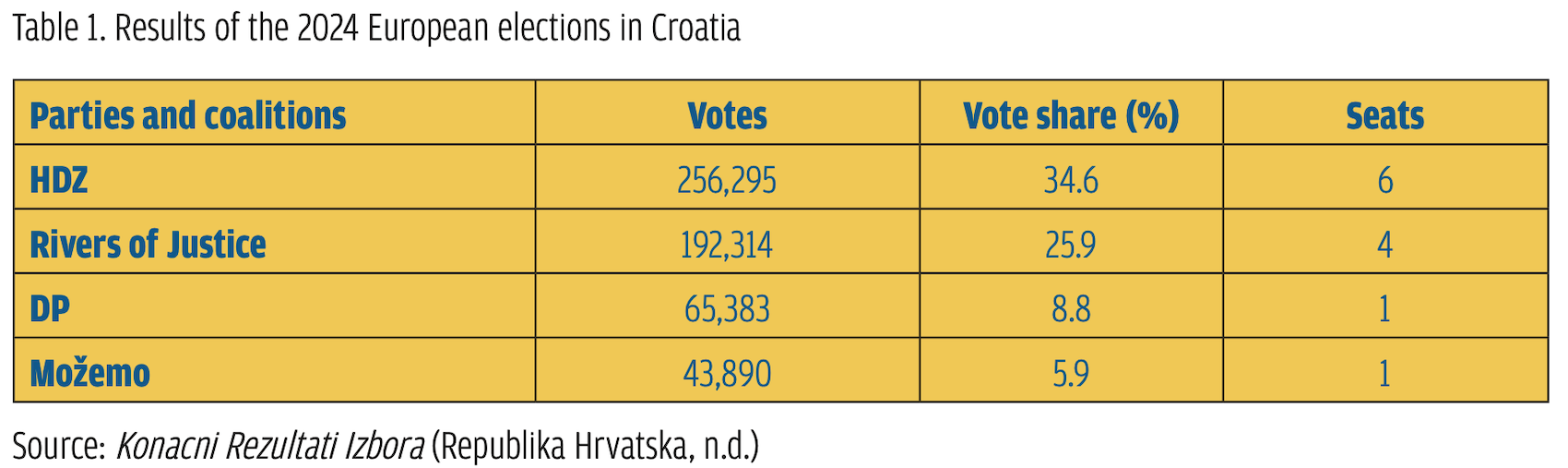

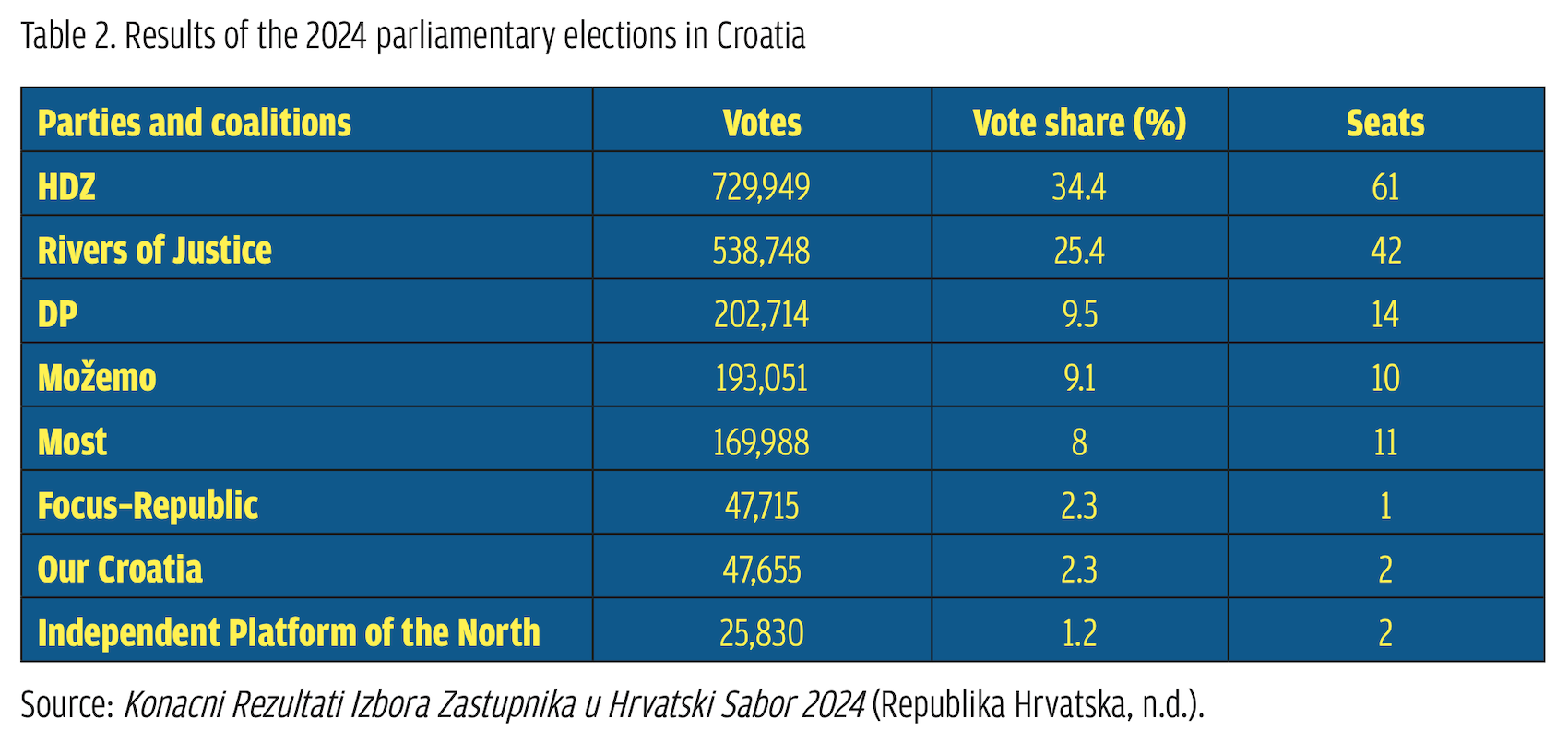

Nevertheless, since not one of these older parties has been represented either in the Croatian Sabor (national assembly) or the EP for longer than a decade, this article focuses on the national conservative party, the Domovinski Pokret (Homeland Movement, DP), which in the short period since its formation has become the most vocal opposition party of the right. In the 2024 European elections, the DP garnered 8.82% of the vote, taking one seat and securing the third spot after the ruling, centre-right Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) and the ‘Rivers of Justice’ coalition spearheaded by the centre-left Social Democrat Party (SDP) (Table 1). Launched on 29 February 2020, the DP has set its principal objective to antagonize the ruling HDZ from the right. This aim acquires a greater significance, considering that roughly one month earlier, under the leadership of Ivan Penava, the DP secured third place in the Croatian parliamentary elections (17 April 2024) with a percentage of 9.56%, taking 14 seats (Table 2). This result, in turn, upgraded the party’s leverage in the negotiations for the formation of a new government after the elections and rendered the DP a ‘kingmaker’ until its official inclusion in the governing coalition with the HDZ in May 2024 (Tesija, 2024; Hajdari, 2024).

I begin the present chapter by sketching a typology of the constituent segments along the broad spectrum of the European right wing and situate the DP within it. I then offer a summary of the DP’s founding principles vis-à-vis further European integration and clarify the extent to which these principles were reflected in the party’s stances and active engagement in the latest European elections. I then identify the main catalysts behind the DP leadership’s success in mobilizing target groups and galvanizing electoral support for the party.

I begin the present chapter by sketching a typology of the constituent segments along the broad spectrum of the European right wing and situate the DP within it. I then offer a summary of the DP’s founding principles vis-à-vis further European integration and clarify the extent to which these principles were reflected in the party’s stances and active engagement in the latest European elections. I then identify the main catalysts behind the DP leadership’s success in mobilizing target groups and galvanizing electoral support for the party.

Situating the Homeland Movement within the European populist and radical right

This schematic categorization pays primary attention to political origins, evolutionary trajectories, and patterns of (active) political engagement (Petsinis, 2019: 166–167). Parties of the populist and radical right tend to scrutinize constitutional order while striving to promote their political cause(s) principally via parliamentary and democratic institutions and procedures. Populist and radical right-wing parties may often be by-products of top-level formation processes (so-called ‘cadre’ parties) that have come into being after (a) the reformation or merger of already existing parties, as with the Sweden Democrats (SD), the Finns Party in Finland, and the Conservative People’s Party (EKRE) in Estonia; or (b) the secession of ‘splinter groups’ from larger parties such as the cases of the Independent Greeks (ANEL) and, more recently, EL in Greece.

Attention must also be paid to one more subcategory of right-wing parties beyond the centre right – the national conservatives. The political platforms of such parties maintain ethnonationalist and nativist components, as well as occasional pledges to protect ‘naturally ascribed’ gender norms and religious values, but their populist and anti-establishment tones appear somewhat less intense. A few representative examples from Central and Eastern Europe are (to a certain extent) Fidesz in Hungary, PiS in Poland and the National Alliance in Latvia.

By contrast, parties of the extreme right may actively challenge (or even attempt to temporarily substitute) the operation of state institutions (e.g., by organizing party militias or youth wings into self-styled ‘street patrols’). Such parties have usually come into being due to processes spearheaded by a grassroots nucleus often aided by semi-paramilitary groupings, therefore regularly opting for a more militant engagement. Parties of this subgroup with a non-negligible public appeal have become active across Central and Southeast Europe – notable cases during the last 10–15 years include the ‘old’ Jobbik in Hungary, ‘Our Slovakia’ (ĽSNS), Bulgaria’s ‘Ataka’, and the Golden Dawn in Greece (Ellinas, 2015; Sygkelos, 2015; Drábik, 2022).

‘Uncompromising opposition’ from the right: Where does the Homeland Movement stand on the issues?

As early as 2020, the DP leadership has set as top priorities: (a) safeguarding of national and Christian values; (b) stricter control of immigration and tougher ‘law and order’ measures, and; (c) revision of certain clauses in legislation protecting minority rights (Domovinski Pokret, 2020a). Regarding the ethnonationalist component of its political agenda, the party objects to the adoption of the ‘fixed’ quota arrangement toward the representation of ethnic minorities in the Sabor (i.e., the so-called ‘electoral district 12’), the ethnic Serb minority in particular (Domovinski Pokret, 2020b: 32). In addition, DP contends that ‘this arrangement has mostly enabled certain individuals and groups to serve their private interests’ (Ibid.: 31) and calls for this model to be abolished (Ibid).

Regarding gender-related issues, DP pledges to ‘respect and safeguard traditional family values’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2020a: 2), whereas the full party manifesto defines ‘marriage as the union between a man and a woman, as stipulated by the Constitution … [T]his guideline must be respected by the Croatian institutions’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2020b: 20). As far as the DP’s nativist principles on immigration are concerned, the party holds that ‘the protection of borders and citizens from potential threats must be assigned primarily to the authorities of sovereign states within the European Union’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2020b: 29).

In their rhetoric, the leader Ivan Penava and other high-ranking members have regularly accused political opponents of ‘incompetence and irresponsibility’, including in attacks on the HDZ for its ongoing cooperation with the ethnic Serb Independent Democratic Party (SDSS) as well as the ‘relentless promotion of pro-LGBT agendas and woke culture’ by the SDP and above all the Green-left coalition of Možemo (‘We Can!’). Nevertheless, the speed with which the current governing coalition between the HDZ and the DP was concluded and the relative flexibility with which any noteworthy obstacles were bypassed hint at a party ostensibly keener on engaging from within the halls of power instead of uncompromisingly opposing the mainstream establishment. Therefore, despite the occasional display of paraphernalia associated with the wartime fascist Ustaše (‘Insurgents’) regime (1941–1945) in public events co-ordinated by the DP (Hajdari, 2024; Novakov & Čolić, 2024), based on top-level decision-making and political values, the DP seems to fit more closely the prototype of a national conservative party. This observation is reinforced by the DP’s joining the ECR group in the EP after the European elections.

The Homeland Movement and the process of European integration

Soon after it was founded and against a backdrop of soft Euroscepticism and concerns over interethnic relations, the DP began expressing discontent with longstanding external pressures from the Venice Commission (Council of Europe) and the EU. This discontent centred on the pre-accession push (in 2000–2002) for Croatia to adopt the ‘fixed’ quota arrangement for ethnic minority representation in the Sabor (Domovinski Pokret, 2020b: 32).

On a macropolitical level, the soft Eurosceptic stance of the DP leadership is reflected in its framing of the European Union as ‘a confederal union of sovereign states and not as a supranational, federal, state with the prospects of becoming unitary’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2020a: 3). Along the same lines, the DP prescribes that Croatia must develop closer relations with the Visegrad Four (Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic) because of ‘the shared historical experiences, as well as the similar positions and outlooks on the European and global developments’ with this group of countries (Domovinski Pokret, 2020b, p. 30). Herein, it should be underlined that, despite its soft Eurosceptic orientation, the DP never advocated for the development of more extensive relations between Croatia and ‘alternative partners’ in global politics, like Russia, China or the BRICS. In this light, the DP seems to align with the staunchly and idiosyncratically sovereigntist stances regarding relations with both the West and non-Western powers that characterize parties to the right of the HDZ in Croatian politics (Petsinis, 2024).

Seizing the geopolitical moment: The Homeland Movement’s reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

The DP leadership has been quick to seize the geopolitical moment occasioned by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Aligning with a more general tendency across Croatia’s political divide, the party’s leader, Ivan Penava, and other high-ranking members have drawn (at times oblique) links between the legacies of Croatia’s Domovinski Rat (1991–1995) and Ukraine’s struggle to resist Russian aggression.

On 24 February 2022, Penava stated, ‘Our party expresses its firm solidarity with Ukraine and the Ukrainian people … we hope that this conflict will last as shortly as possible with as few human and material losses as possible’ (Ibid.). He also urged the state authorities to organize the accommodation of Ukrainian refugees in Croatia and efficiently allocate the material resources required. In addition to highlighting the commonalities between the Homeland War and the developments in Ukraine, Penava cast doubts on the competence of the government to manage a migration crisis in Croatia (Ibid.). More emphatically, on 6 April 2022, the party’s MP Stipo Mlinarić praised Volodymyr Zelenskyy for dealing with the ‘fifth column’ in Ukraine and deplored the fact that ‘the HDZ-led government has not done the same with the ‘fifth column’ that operates from within the Serb Democratic Independent Party’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2022b).

Nevertheless, between Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 and the end of 2023, the DP suffered a plateauing, if not a significant decline, in its popularity vis-à-vis the HDZ and other minor contenders on the right. As indicated in several public surveys conducted by the Promocija Plus, 2X1 Komunikacije and Ipsos polling agencies between March and December 2022, the DP had been lagging behind both Možemo and the centre-right, conservative Most (‘The Bridge’) party (Europe Elects, 2024). Therefore, to reverse this decline in popularity, the DP started putting greater stress on the rapidly increasing cost of living and the government’s alleged incompetence in dealing with galloping inflation (Domovinski Pokret, 2022c).

Due to this change of course and the party’s gradual adoption of a strategy more focused on domestic policy, which persisted until the Croatian parliamentary and the European elections, no extensive or concrete references were made to the war in Ukraine. On the contrary, the DP’s Ustani i Ostani! (‘Stand Up and Remain!’) political program, which the party launched for both the national and the European elections, cites Ukraine only on one occasion: in the section about national defence and the need to upgrade the equipment of the Croatian armed forces – the navy, in particular. In greater detail, the program stresses that: ‘Ukraine demonstrated how the use of new military technologies, such as drones, can paralyse even the naval forces of global superpowers (namely, Russia)’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2024a: 23). Otherwise, any references by DP to the EU during its campaign for the European elections concentrated on more general aspects of European politics in accordance with the party’s founding principles regarding the process of European integration.

The Homeland Movement’s campaign in the 2024 European elections

Right at the beginning of the Ustani i Ostani! policy document, the DP underlines its fundamental stance on state sovereignty within the EU: “Many types of crises during the last years (e.g., the financial crisis, Brexit, the migration crisis, and the COVID-19 crisis) have demonstrated that the EU reacts in a slow and non-coordinated manner whereas, at the same time and under these irregular circumstances, the member states prioritize their own interests exclusively. This is why Croatia must prioritize its own interests, too (Croatia comes first!)” (Domovinski Pokret, 2024a: 26).

At a later point in the same policy document, the DP leadership reiterates that it is a sovereigntist party which primarily views the EU as ‘a community of equal and sovereign states and nations rooted in Christian foundations and principles … the detachment of the EU from its Christian roots has resulted in great identity confusion’ (Ibid). Furthermore, the party contends that ‘decisions about Croatia should be taken by Croatian politicians in Zagreb and not by Brussels-based officials’ (Ibid). With specific regard to the area of national defence and the prospects for the EU’s strategic autonomy, DP holds that any projects designed to bolster EU defence policy must not be misused by Brussels in order to weaken further the sovereignty of nation-states (Domovinski Pokret, 2024a: 26).

In addition, DP adamantly opposes Serbia’s accession to the EU, in no small part due to the legacies of the wars of the 1990s in which Serbia is seen as the aggressor against Croatia. Contrarywise, the party underlines that ‘the things that Croatia must demand without compromise from Serbia, which committed aggression on Croatian territory, are payment of war reparations, a thorough search for disappeared persons, and the return of cultural treasures that were stolen during the war’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2024a: 28). At the same time, the party accuses the Serbian government of ‘promoting the ideology of Greater Serbia and openly endorsing Russian aggression against Ukraine’ (Ibid).

Apart from Ustani i Ostani!, individual MPs reiterated these standpoints concerning major policymaking areas on the EU level, both in the Croatian and the European Parliaments, on numerous occasions. Regarding immigration, in the aftermath of a knife attack in Mannheim, Germany, in May 2024, Ivo Čaleta-Car, a DP deputy in the Sabor, warned in a speech that:

The EU is slowly turning into a unitary supranational state. The EU is trying to create an unnatural federation of states that will be held together by migrants and their descendants through mixing with the indigenous populations (Domovinski Pokret, 2024b).

In the same speech, he stressed: ‘Yes to the EU as a community of sovereign nations! No to the EU as a superstate!’ (Ibid.). Moreover, DP concisely but effectively publicized and summarized its main standpoints on European politics through the party’s official pages on social media (e.g., X and Instagram). On the party’s Instagram page, for instance, its main slogans for the European elections feature as follows: “‘Croatia comes first!’, ‘We stop the extension of the Brussels’ jurisdiction!’, ‘For a counteraction to the globalist agendas!’, ‘No to the propagation of gender ideology! We do not want gender ideology in our schools!’, ‘For the protection of national borders!’, ‘For the demographic rebirth of Croatia and Europe!’, ‘Rebirth of the village for the rebirth of Croatia and Europe!’, ‘For a Europe that respects its Christian foundations!’” (Domovinski Pokret, 2024c).

Here, it should be noted that several party candidates incorporated slogans related to policies on the EU level into their campaigns for both the national and the European elections. Stipe Mlinarić, for instance, reiterated that ‘Serbia cannot join the EU before it pays Croatia war reparations for the villages and towns that it destroyed’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2024d), Meanwhile, other party candidates pledged to fight for ‘a Europe that respects its Christian foundations’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2024e), reiterated that ‘Croatia must retain its sovereignty in Europe’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2024f), and underlined that ‘Christianity is the foundation of the EU’ (Domovinski Pokret, 2024g).

Embedding the European in the national: A contextual analysis of the Homeland Movement’s political strategy in the European elections of 2024

With a turnout rate of 21.35%, Croatia had the lowest voter participation among all EU member states in the most recent European elections. Croatians’ lack of interest is underscored if we compare this turnout with the much higher rate of 62.30% in the Croatian parliamentary elections that took place on 17 April 2024 (Republika Hrvatska, n.d.). With European elections held shortly after the parliamentary ones, it is clear that Croatia’s major political leaders prioritized the latter. This was especially true for DP, which emerged as a ‘kingmaker’ after the national elections. Faced with a choice between continuing its role as a perennial gadfly berating the HDZ establishment from opposition or seeking real power on the inside, DP leader Ivan Penava chose the latter, aligning his party with the HDZ and joining it in a governing coalition.

Considering the relatively more ‘parochial’ outlook of the Croatian electorate on global and European politics, the DP’s leadership has since 2020 been rather eclectic and places primary stress on those developments that, due to sociocultural catalysts, might resonate more directly with the ‘collective subconscious’ of the party’s target groups. This appears to have been a fairly commonplace practice for right-wing political actors in Croatia. For instance, between 2018 and 2019 (two years prior to the formation of the DP), the ‘right-wing faction’ within the ruling HDZ extensively capitalized on public grievances vis-à-vis the guidelines of the ‘Istanbul Convention’ for LGBTQ+ rights and gender equality (Milekic, 2018). Along comparable lines, the DP sought to capitalize on the shockwaves that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine generated across Croatian society by drawing tentative links between Ukrainian resistance and the Croatian Domovinski Rat in the 1990s. However, after 2023, the party leadership switched to a more domestic-focused strategy, emphasizing the rapidly increasing cost of living and Croatia’s galloping inflation as part of the endeavour to reverse its declining popularity.

Consequently, in its political program and the individual campaigns of its candidates and the party’s social media, the DP adopted an even more eclectic pattern of engagement for the European elections that consisted of (a) frequent and repetitive use of ‘catchphrase’ slogans (e.g., ‘Croatia comes first!’) and (b) a paramount, yet synoptic, stress on these aspects of European politics that resonated the most with the party’s founding principles and the dominant trends on identity politics among its target groups in the electorate. Therefore, primary importance was placed on (a) the purported need to safeguard Croatia’s state sovereignty from any extension of the EU’s jurisdiction; (b) calls to veto Serbia’s accession to the EU; (c) opposition to the alleged propagation of ‘gender ideology’ and counter-proposals in increase birthrates in Croatia and the rest of Europe, and; (d) the effective protection of national borders and stricter regulation of immigration from ‘third’ countries outside of Europe.

In the long run, it appears that this more eclectic strategy, which prioritized the embedment of the European in the national, facilitated the DP’s galvanizing of the groupness of its electorate, especially in the strongholds of Eastern and Western Slavonia (i.e., the IV. and V. electoral districts) and claim the third spot behind the HDZ and the SDP (but ahead of Most and Možemo) in both the parliamentary and European elections. Slavonia, as a whole, is a region that was heavily scarred by protracted warfare during the first half of the 1990s. In particular, Vukovar, an Eastern Slavonian town on the border with Serbia along the western bank of the Danube, has been established as a ‘master symbol’ of resistance to the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) in Croatian nationalist imagery. Most importantly, Vukovar is the town of which Ivan Penava has been the local mayor since 2014. The long-term evolution of the HDZ–DP coalition will demonstrate whether the party leadership is keener on (a) alleviating its stances on Euroscepticism and identity politics to secure its status more firmly inside the halls of power or (b) seeking a ‘new’ pact with the ideologically compatible ‘right-wing faction’ within the ruling HDZ in an attempt to trigger a more decisive swing of the governing coalition towards the right.

(*) Vassilis Petsinis (PhD Birmingham UK) is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the Corvinus University (Institute of Global Studies) in Budapest, Hungary. He is a political scientist with expertise in European Politics and Ethnopolitics. His Marie Skłodowska-Curie (MSCA-IF) individual research project at the University of Tartu (2017–19) was entitled: ‘Patterns and management of ethnic relations in the Western Balkans and the Baltic States’ (project ID: 749400-MERWBKBS). Vassilis Petsinis is a specialist in the politics of Central and Eastern Europe. He is the author of the monographs National Identity in Serbia: The Vojvodina and a Multiethnic Community in the Balkans (Bloomsbury, 2020) and Cross-regional Ethnopolitics in Central and Eastern Europe: Lessons from the Western Balkans and the Baltic States (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), as well as other academic publications that cover a range of countries as diverse as Serbia, Croatia, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia and Greece.

References

Domovinski Pokret. (2020a). Parlamentarni Izbori 2020: Zašto Što Svoje Volim. Domovinski Pokret.

Domovinski Pokret. (2020b). Program Delovanja, lipanj 2020. Domovinski Pokret.

Domovinski Pokret. (2022a, February 24). ‘Penava: Domovinski Pokret Iskazao Solidarnost s Ukrajinom i Ukrajinskom Narodom’. Retrieved 22 September 2024 from https://www.dp.hr/blog/Penava_Domovinski_pokret_iskazao_solidarnost_s_Ukrajinom_i_ukrajinskim_narodom/544

Domovinski Pokret. (2022b, April 6). ‘Mlinarić: Za razliku od Ukrajine, mi se Još Nismo Obračunali sa Svojom Petom Kolonom’. Retrieved 22 September 2024 from https://www.dp.hr/blog/Mlinaric_Za_razliku_od_Ukrajine__mi_se_jos_nismo_obracunali_sa_svojom_petom_kolonom/553

Domovinski Pokret. (2022c, September 8). ’Kada je Država Skupa i Neučinkovita, Nema te Mjere Koja Je Može Spasiti!’ Retrieved 22 September 2024 from https://www.dp.hr/blog/Kada_je_drzava_skupa_i_neucinkovita__nema_te_mjere_koja_je_moze_spasiti/593

Domovinski Pokret. (2024a). Politički Program: Ustani i Ostani! Domovinski Pokret.

Domovinski Pokret. (2024b). ‘Ćaleta-Car: EU kao zajednica suverenih nacija da, EU kao nadnacionalna naddržava ne!’, https://www.instagram.com/p/C8XZBJDCYO1/

Domovinski Pokret. (2024c). ‘Hrvatice i Hrvati, izađite na izbore za EU parlament i podržite program Domovinskog pokreta’, https://www.instagram.com/p/C7vxzG6iyXz/

Domovinski Pokret. (2024d). ‘Mlinarić: Srbija ne može ući u EU dok ne plati ratnu odštetu Hrvatskoj za porušena sela i gradove!’, https://www.instagram.com/p/C7d41zDK7vo/

Domovinski Pokret. (2024e). ‘Bartulica: Za Europu koja poštuje svoje kršćanske temelje!’, https://www.instagram.com/p/C7jE99YC8gX/

Domovinski Pokret (2024f). ‘Vaš suverenistički glas u Europi!’ https://www.instagram.com/p/C7PSe2iCcNz/

Domovinski Pokret (2024g). ‘Lozo: U Europskom parlamentu zauzimat ćemo se za zaštitu tradicionalnih vrijednosti i očuvanje Europe na kršćanskim osnovama’, https://www.instagram.com/p/C7zTI0rCA8u/?img_index=1

Drábik, J. (2022). ‘“With Courage against the System”. The Ideology of the People’s Party Our Slovakia’. In Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe, 30 (3), p.p.417–434.

Ellinas, A. (2015). ‘Neo-Nazism in an Established Democracy: The Persistence of Golden Dawn in Greece’. In South European Society and Politics, 20(1), pp.1–20.

European Parliament. (n.d.). 2024 European Parliament elections: Turnout. European Parliament Election Results. Retrieved 22 September 2024, from https://results.elections.europa.eu/en/turnout/

Europe Elects. (2024). ‘Croatia: National Poll Average’, Retrieved 22 September 2024, from https://europeelects.eu/croatia/

Hajdari, U. (2024). ‘Croatia Election Winner Cozies up with Far Right in New Government’ in Politico, 9 May 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/croatia-forms-far-right-government-homeland-movement-croatian-democratic-union-andrej-plenkovic/

Milekic, S. (2018). ‘Croatian Conservatives Protest Against Anti-Violence Treaty’ in Balkan Insight, 13 April 2018, https://balkaninsight.com/2018/04/13/anti-istanbul-convention-protesters-turn-against-croatian-pm-04-13-2018/

Novakov, S. and Čolić, N. (2024). ’Ekstremna Desnica Postaje Krojač Sudbine Hrvatske’ in NIN, 20 April 2024, https://www.nin.rs/svet/vesti/48239/domovinski-pokret-kao-tas-na-vagi-ko-ce-formirati-vladu-u-hrvatskoj

Petsinis, V. (2019). ‘Hijacking the Left? ‘The Populist and Radical Right in Two Post-Communist Polities’. In G. Charalambous & G. Ioannou (Eds.), Left Radicalism and Populism in Europe (pp. 156–180). Routledge.

Petsinis, V. (2024). ‘National Conservative, Radical, and Extremist Right-wing Parties in Croatia: A Critical Retrospective Overview’ in Péter Marton, Gry Thomasen, Csaba Békés and András Rácz (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Non-State Actors in East-West Relations (pp. 1–17). Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Republika Hrvatska. (n.d.). Konačni rezultati izbora. Retrieved 22 September 2024 from https://www.izbori.hr/sabor2024/rezultati/

Sygkelos, Y. (2015). ‘Nationalism versus European Integration: The Case of ATAKA’, In East European Quarterly, 43(2–3), pp.163–188.

Tesija, V. (2024). ‘Croatia’s HDZ Secures Third Govt Term in Alliance with Far-Right’ in Balkan Insight, 8 May 2024, https://balkaninsight.com/2024/05/08/croatias-hdz-secures-third-govt-term-in-alliance-with-far-right/

Within this period, Bulgaria had two short-lived regular governments. A new coalition government was formed in December after the November 2021 elections, under the premiership of Kiril Petkov, uniting the winner of the election PP (25.67%) with three coalition partners—BSP, ITN and the DB alliance. The government survived until June 2022, when it was removed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence initiated by GERB after ITN ended its support for the government and withdrew its members from ministerial posts. The Petkov government had the difficult task of dealing with the war in Ukraine, which erupted in February 2022 and divided public opinion in Bulgaria. With a large pro-Russian population, the war enabled parties like Vazrazhdane to thrive while constraining the government to maintain a delicate balance between the country’s commitment to its Euro-Atlantic partners and pressure from pro-Russian groups. Although Bulgaria enforced EU sanctions on Russia, phased out Russian oil deliveries, and provided military support for Ukraine, there has been continuous opposition from both inside and outside the National Assembly to these actions (Zankina, 2023).

Within this period, Bulgaria had two short-lived regular governments. A new coalition government was formed in December after the November 2021 elections, under the premiership of Kiril Petkov, uniting the winner of the election PP (25.67%) with three coalition partners—BSP, ITN and the DB alliance. The government survived until June 2022, when it was removed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence initiated by GERB after ITN ended its support for the government and withdrew its members from ministerial posts. The Petkov government had the difficult task of dealing with the war in Ukraine, which erupted in February 2022 and divided public opinion in Bulgaria. With a large pro-Russian population, the war enabled parties like Vazrazhdane to thrive while constraining the government to maintain a delicate balance between the country’s commitment to its Euro-Atlantic partners and pressure from pro-Russian groups. Although Bulgaria enforced EU sanctions on Russia, phased out Russian oil deliveries, and provided military support for Ukraine, there has been continuous opposition from both inside and outside the National Assembly to these actions (Zankina, 2023).

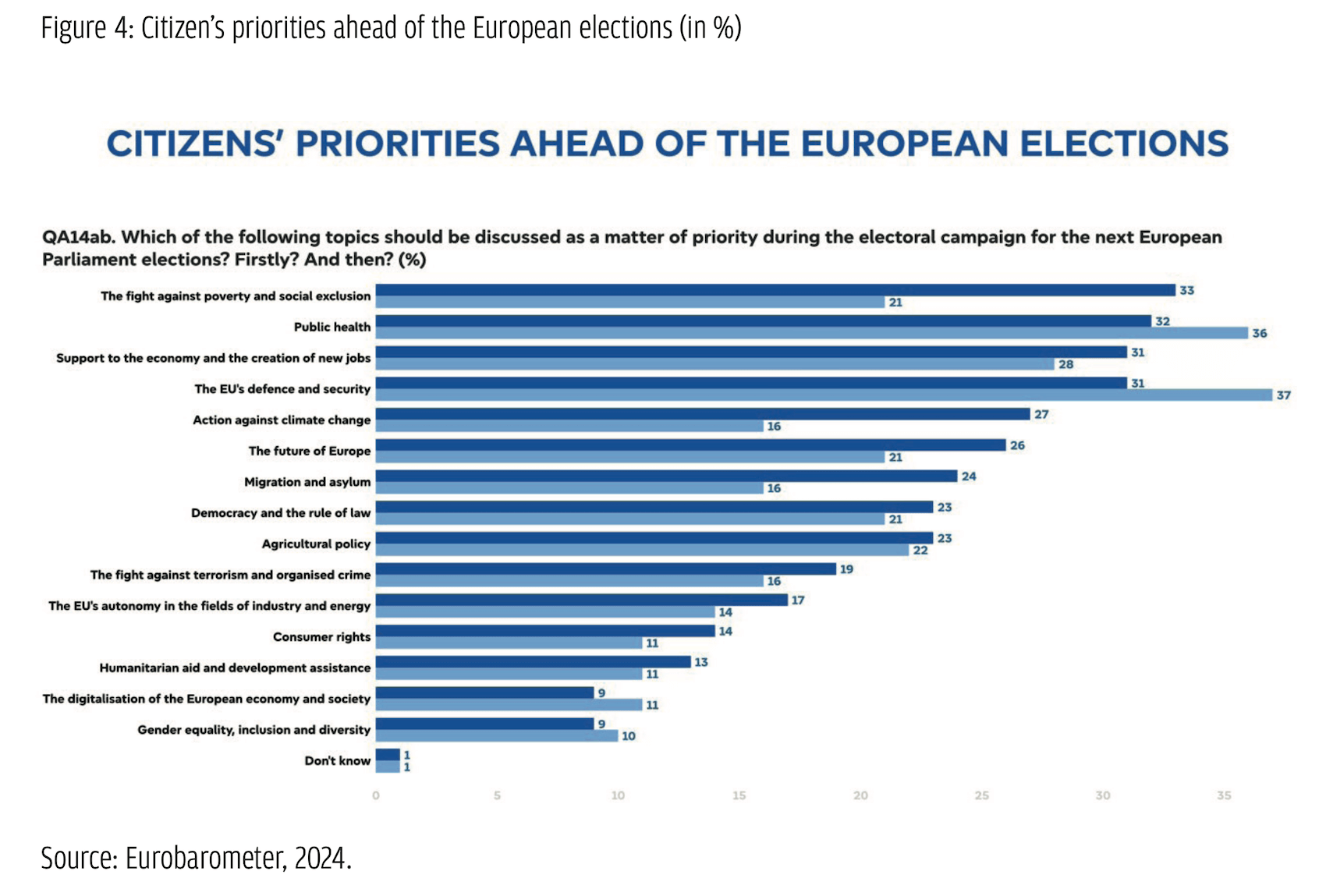

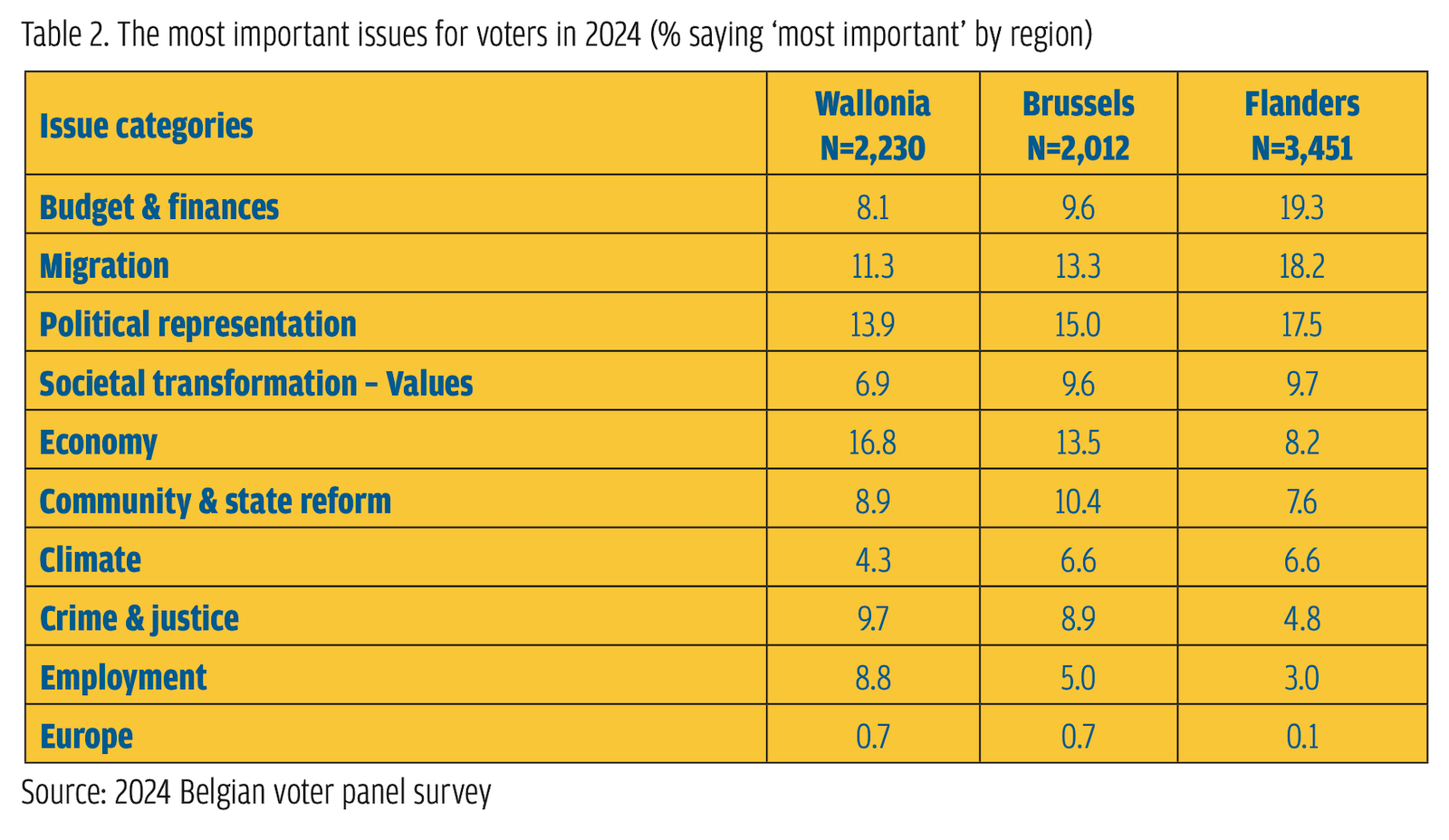

More importantly, the two-in-one elections significantly shifted the debate towards domestic issues. Opinion polls indicated corruption (59%), low income (57%), and healthcare (45%) to be the top three issues of voter concern (Alpha Research 2024a), while poverty and equality were singled out as the top priorities the EU should focus on (Trend 2024). Rising prices and increased cost of living (56%) along with the economic situation (53%) were the main motivators for Bulgarian voters – much more so than the EU average of 42% and 41%, respectively (Eurobarometer 2024).

More importantly, the two-in-one elections significantly shifted the debate towards domestic issues. Opinion polls indicated corruption (59%), low income (57%), and healthcare (45%) to be the top three issues of voter concern (Alpha Research 2024a), while poverty and equality were singled out as the top priorities the EU should focus on (Trend 2024). Rising prices and increased cost of living (56%) along with the economic situation (53%) were the main motivators for Bulgarian voters – much more so than the EU average of 42% and 41%, respectively (Eurobarometer 2024).  GERB convincingly won the 2024 European Parliament elections with 23.55% of the votes and five seats. Second came Dvizhenie za Prava i Svobodi (Movement for Rights and Freedoms, DPS) with 14.66% of the votes and three seats, closely followed by the PP–DB alliance, with 14.45% and the same number of seats, and Vazrazhdane (Revival) with 13.98% and also three seats. While pro-EU parties received the majority of the votes in the election, the results of Vazrazhdane and the increase of radical-right MEPs from 2 to 3 are a cause for great concern amidst an overall rise of the populist radical right in the European Parliament.

GERB convincingly won the 2024 European Parliament elections with 23.55% of the votes and five seats. Second came Dvizhenie za Prava i Svobodi (Movement for Rights and Freedoms, DPS) with 14.66% of the votes and three seats, closely followed by the PP–DB alliance, with 14.45% and the same number of seats, and Vazrazhdane (Revival) with 13.98% and also three seats. While pro-EU parties received the majority of the votes in the election, the results of Vazrazhdane and the increase of radical-right MEPs from 2 to 3 are a cause for great concern amidst an overall rise of the populist radical right in the European Parliament.

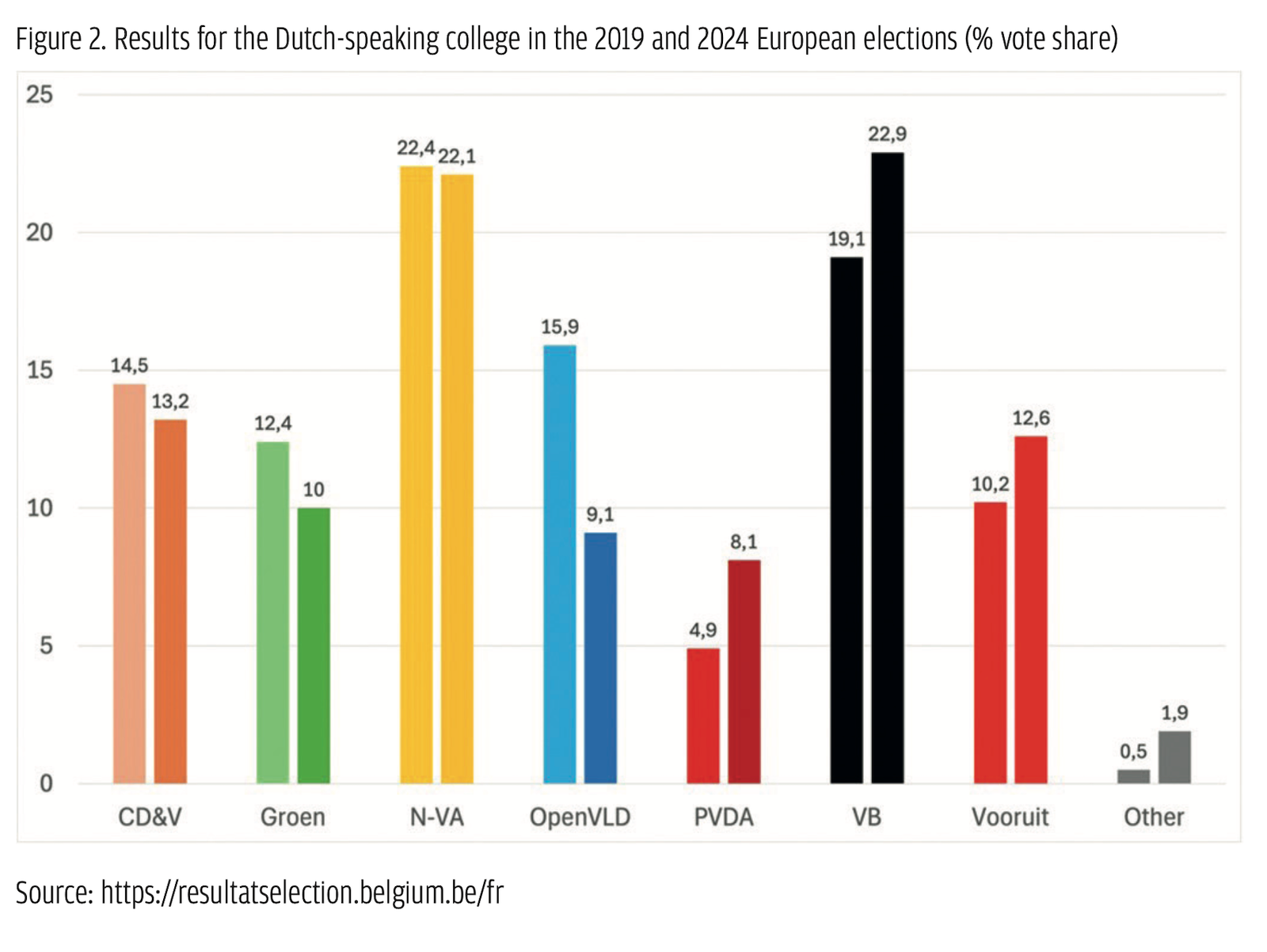

Among these parties, two are clear cases of populist radical parties based on the PopuList categorization

Among these parties, two are clear cases of populist radical parties based on the PopuList categorization

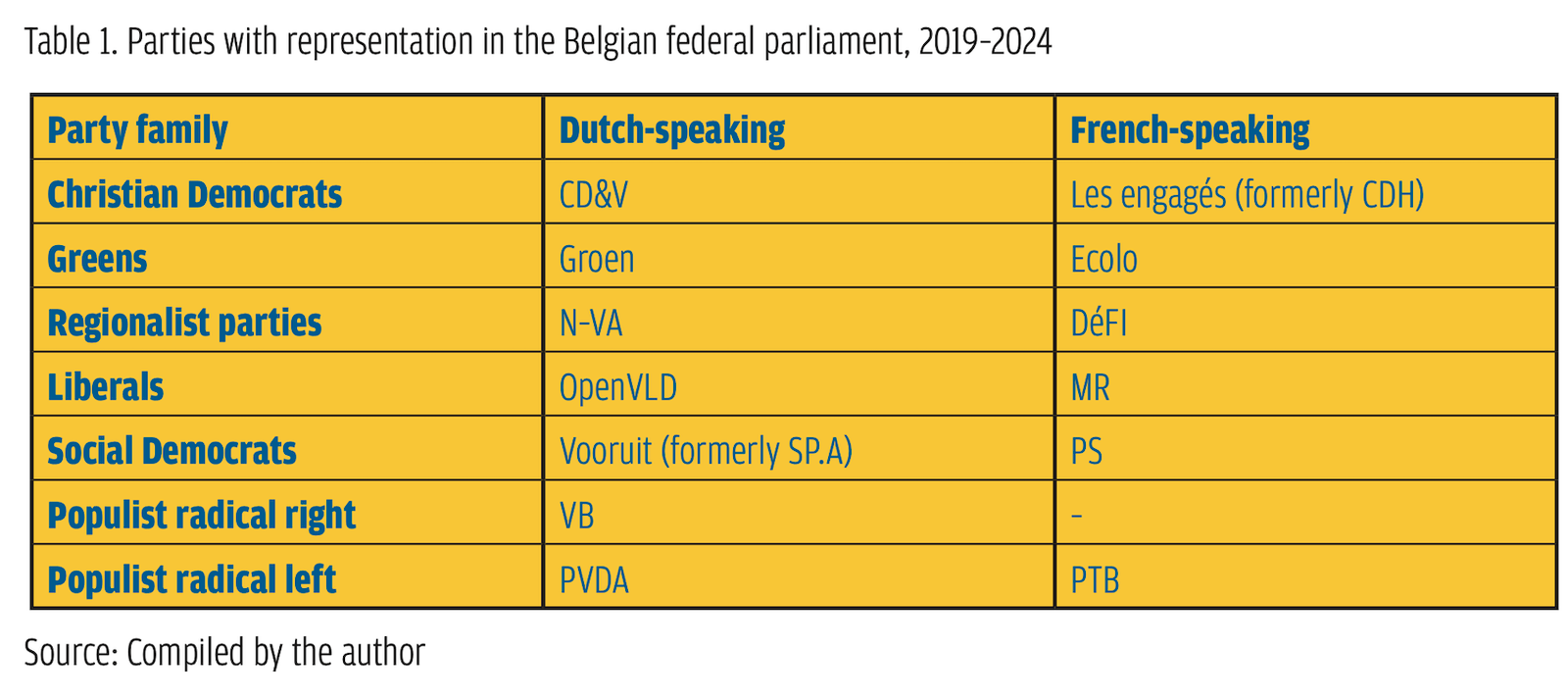

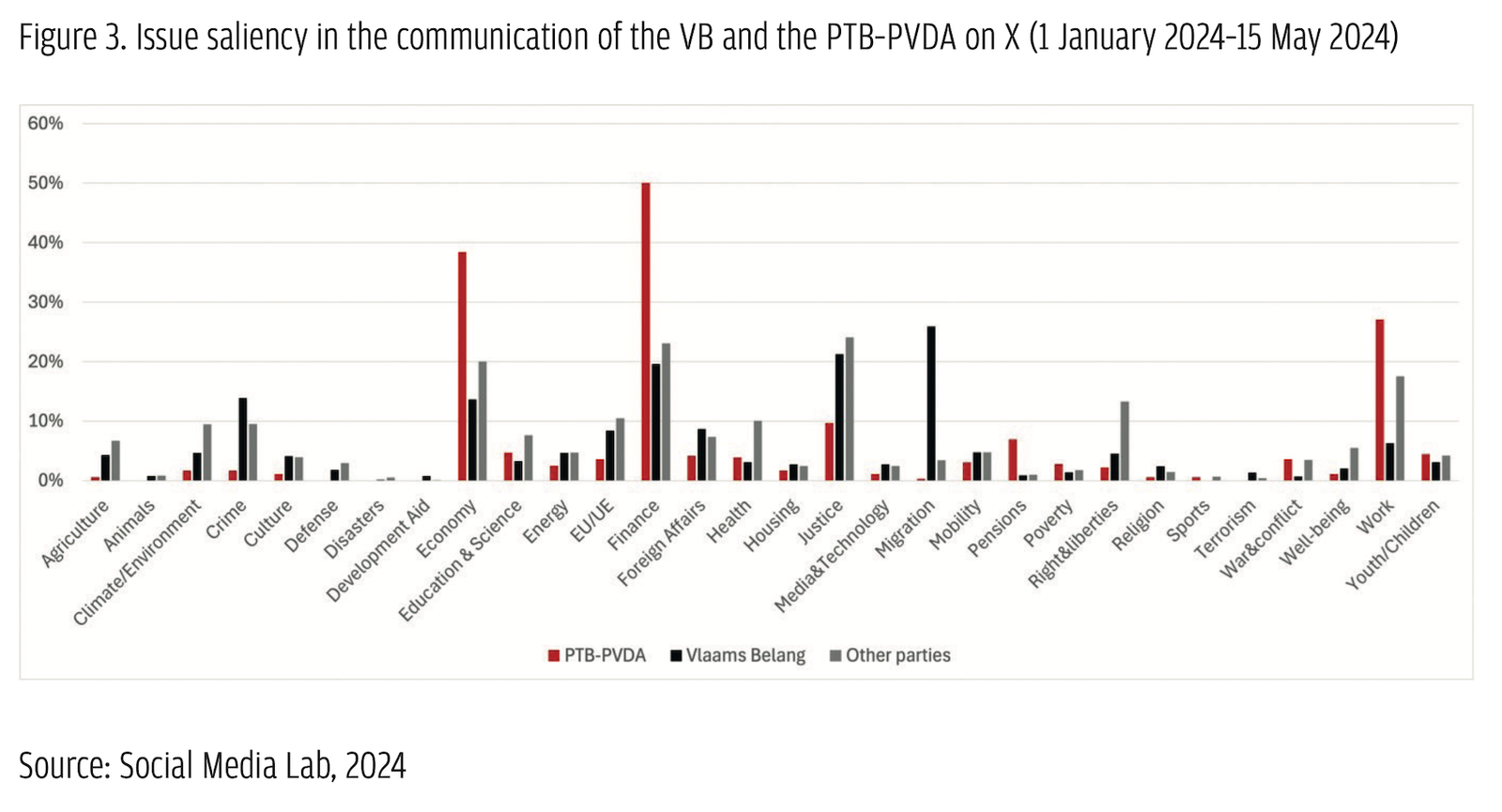

The profile of VB and PTB–PVDA voters in 2019 presented similarities. Data from the 2019 Belgian panel survey (Michel et al., 2024) show that both parties attracted a younger, more male voter group with lower levels of education and a protest component, and displaying lower levels of trust and satisfaction with the government, but also higher levels of anger (Gallina et al., 2020; Jacobs et al., 2024). Populist radical parties thus clearly capitalized on voters seeking an alternative. But they also attracted issue-based voting on their core respective issues (Goovaerts et al., 2020; Walgrave et al., 2020).

The profile of VB and PTB–PVDA voters in 2019 presented similarities. Data from the 2019 Belgian panel survey (Michel et al., 2024) show that both parties attracted a younger, more male voter group with lower levels of education and a protest component, and displaying lower levels of trust and satisfaction with the government, but also higher levels of anger (Gallina et al., 2020; Jacobs et al., 2024). Populist radical parties thus clearly capitalized on voters seeking an alternative. But they also attracted issue-based voting on their core respective issues (Goovaerts et al., 2020; Walgrave et al., 2020). While the content reveals the ideological focus of these parties, the tone of their communication connects to their populist core. Both parties heavily rely on attacks as a mode of communication. Previous studies have shown that personal or programmatic attacks represent 26.5% of the total communication of the VB on X (first party in Belgium) and 25% for the PTB–PVDA (Close et al., 2023).

While the content reveals the ideological focus of these parties, the tone of their communication connects to their populist core. Both parties heavily rely on attacks as a mode of communication. Previous studies have shown that personal or programmatic attacks represent 26.5% of the total communication of the VB on X (first party in Belgium) and 25% for the PTB–PVDA (Close et al., 2023).

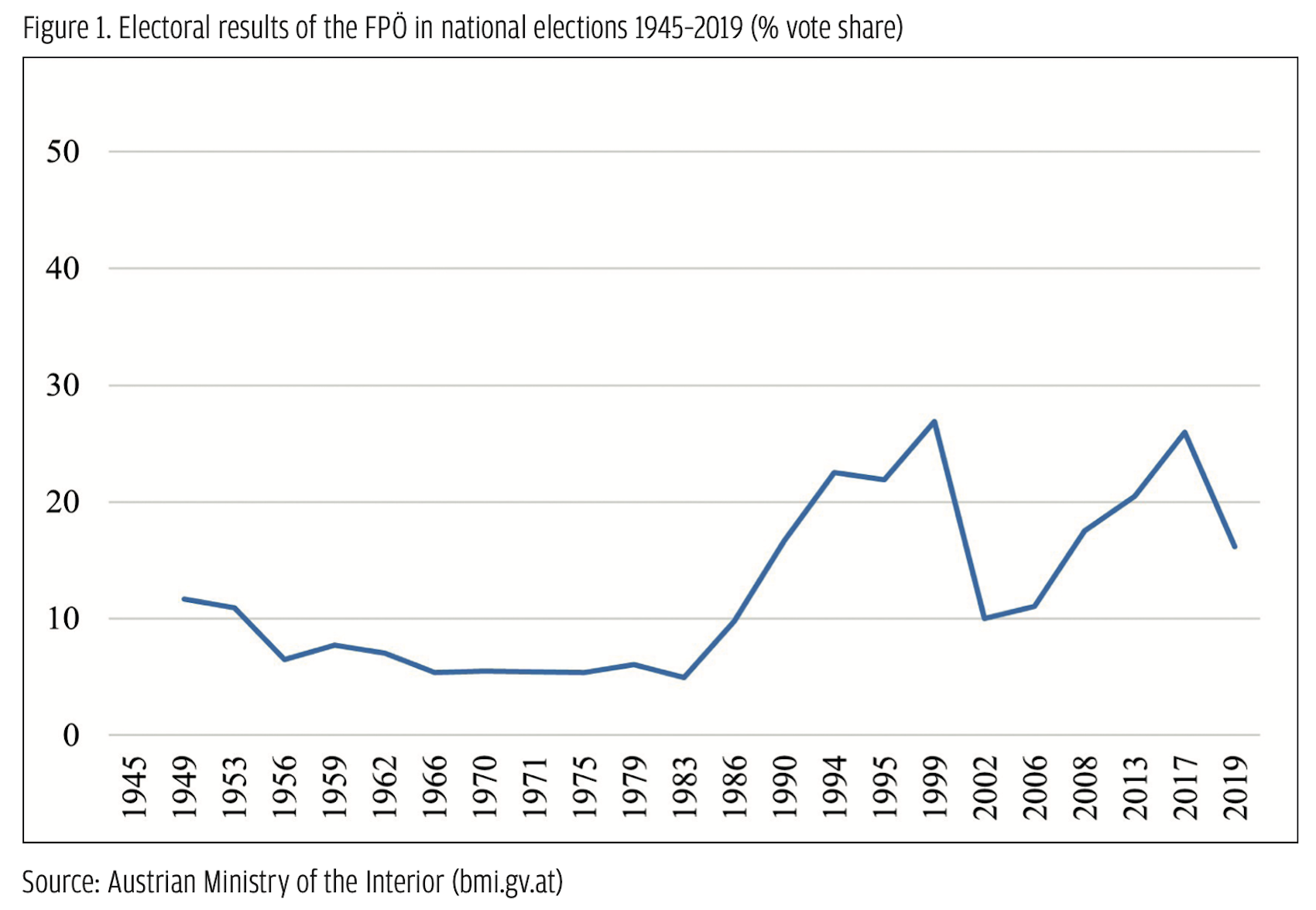

During the 2024 EU elections, the FPÖ was the only populist party represented in the Austrian parliament. The only other party that might be classified as populist that ran in the elections was the Democratic, Neutral, Authentic (DNA) list led by a former physician and anti-vaccine activist, who played an active role in protests directed against the protective measures taken by the Austrian government during the COVID-19 pandemic. This party, however, was founded just months before the elections, received hardly any media- and public attention, and failed to win a seat, taking just 2.7% of the votes. The following report will therefore restrict its focus to the FPÖ.

During the 2024 EU elections, the FPÖ was the only populist party represented in the Austrian parliament. The only other party that might be classified as populist that ran in the elections was the Democratic, Neutral, Authentic (DNA) list led by a former physician and anti-vaccine activist, who played an active role in protests directed against the protective measures taken by the Austrian government during the COVID-19 pandemic. This party, however, was founded just months before the elections, received hardly any media- and public attention, and failed to win a seat, taking just 2.7% of the votes. The following report will therefore restrict its focus to the FPÖ. The demand side of the EU: Critical populism in Austria

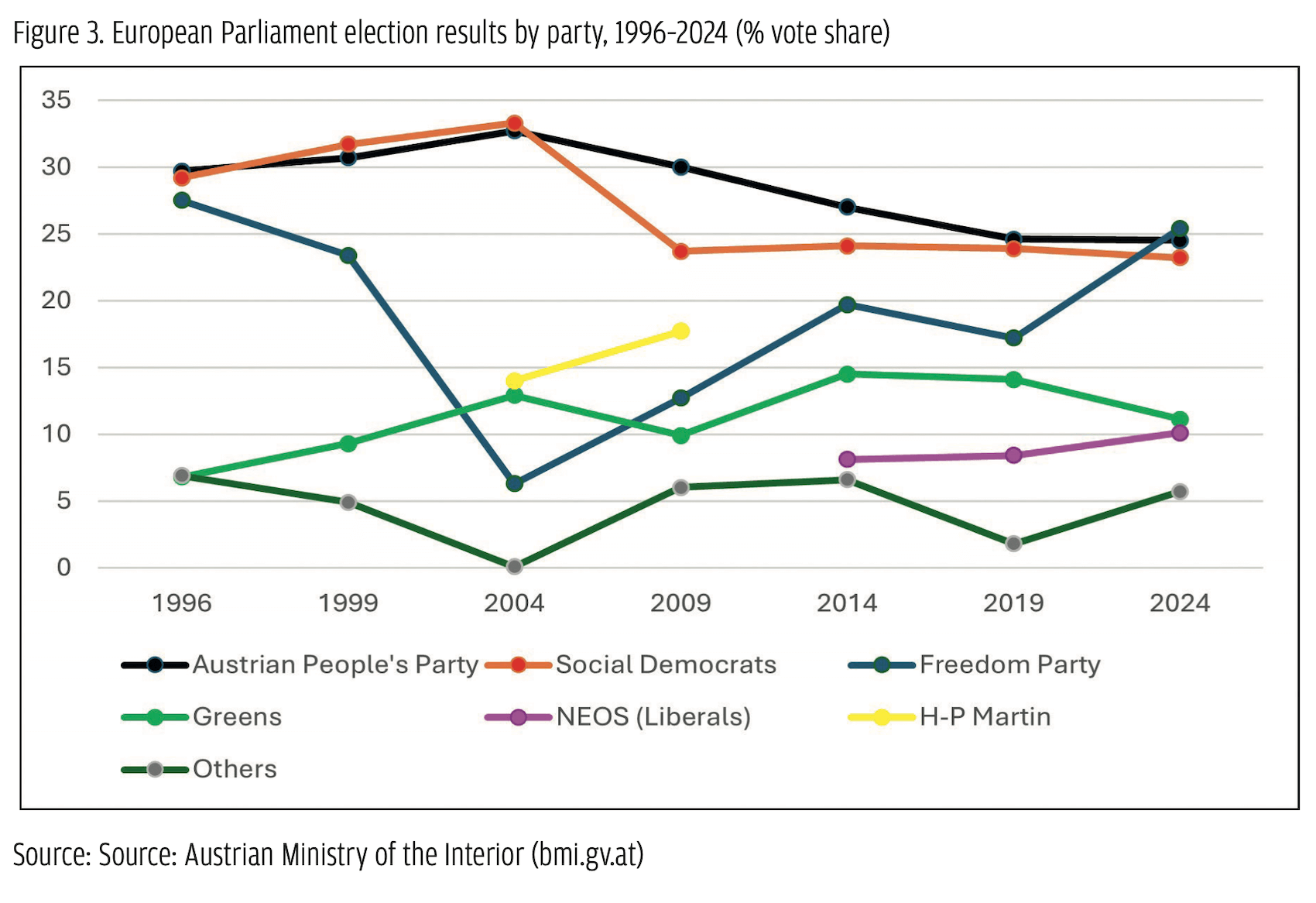

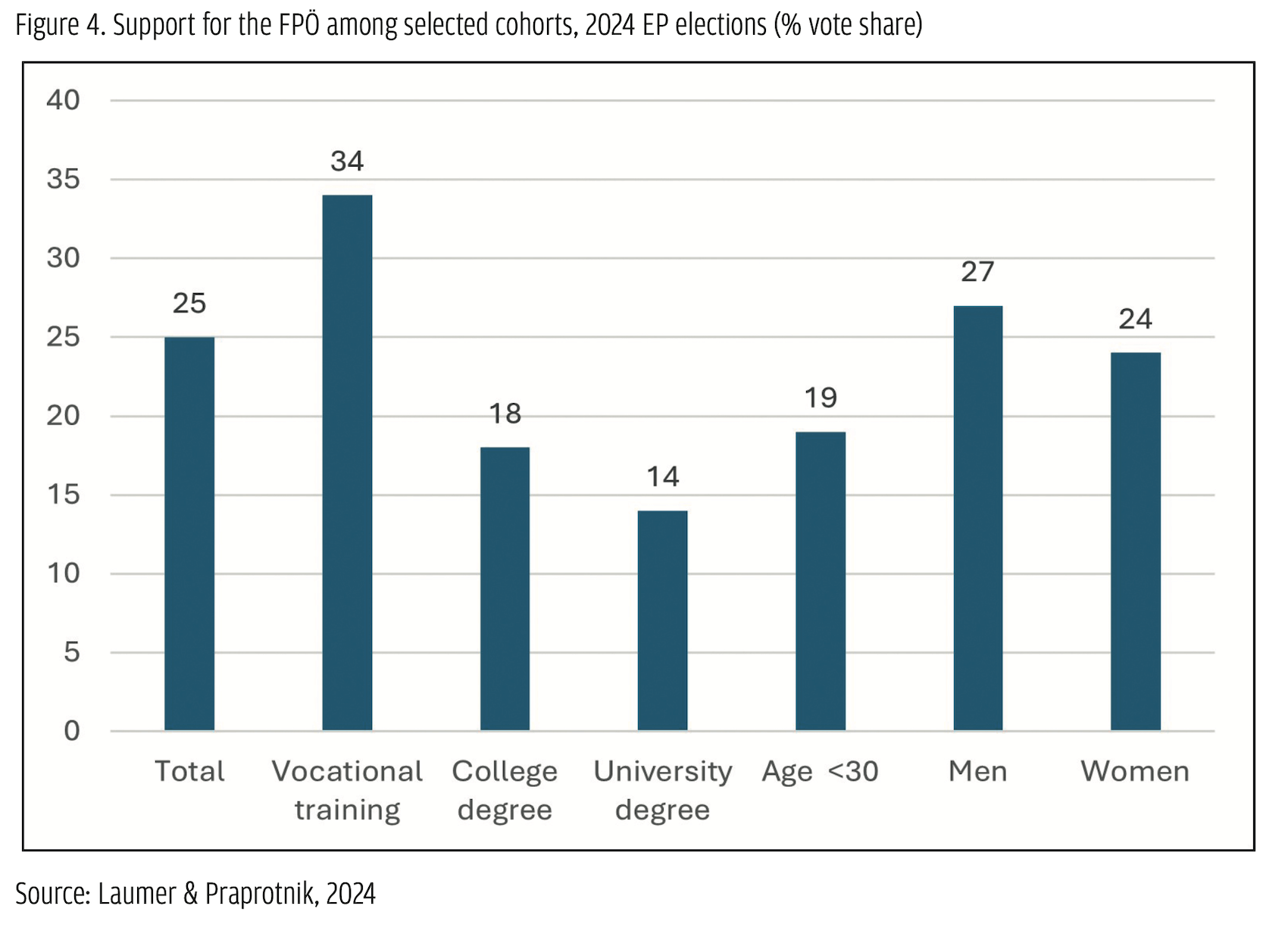

The demand side of the EU: Critical populism in Austria Looking at sociodemographic characteristics (Figure 3), the FPÖ somewhat underperformed amongst voters below the age of 30. Regarding education, it was most successful amongst voters who had completed vocational training and least successful amongst high-school and university graduates. Interestingly, and in line with preceding regional elections (Salzburger Nachrichten, 2024), the once significant gender gap has shrunk considerably compared to the elections in 2019. While back then, 26% of men but only 10% of women voted for the FPÖ, this time it was 27% of men compared to 24% of women. Amongst voters holding at least a college degree, the gap even vanished entirely, with 16% of men and 17% of women opting for the FPÖ (Laumer & Praprotnik, 2024). Amongst others, these changes may be a consequence of the position the party took during the COVID-19 pandemic (especially its critique to discriminate restrictions between vaccinated and non-vaccinated citizens) – which was also found among many (also highly-educated) women (Die Presse, 2021).

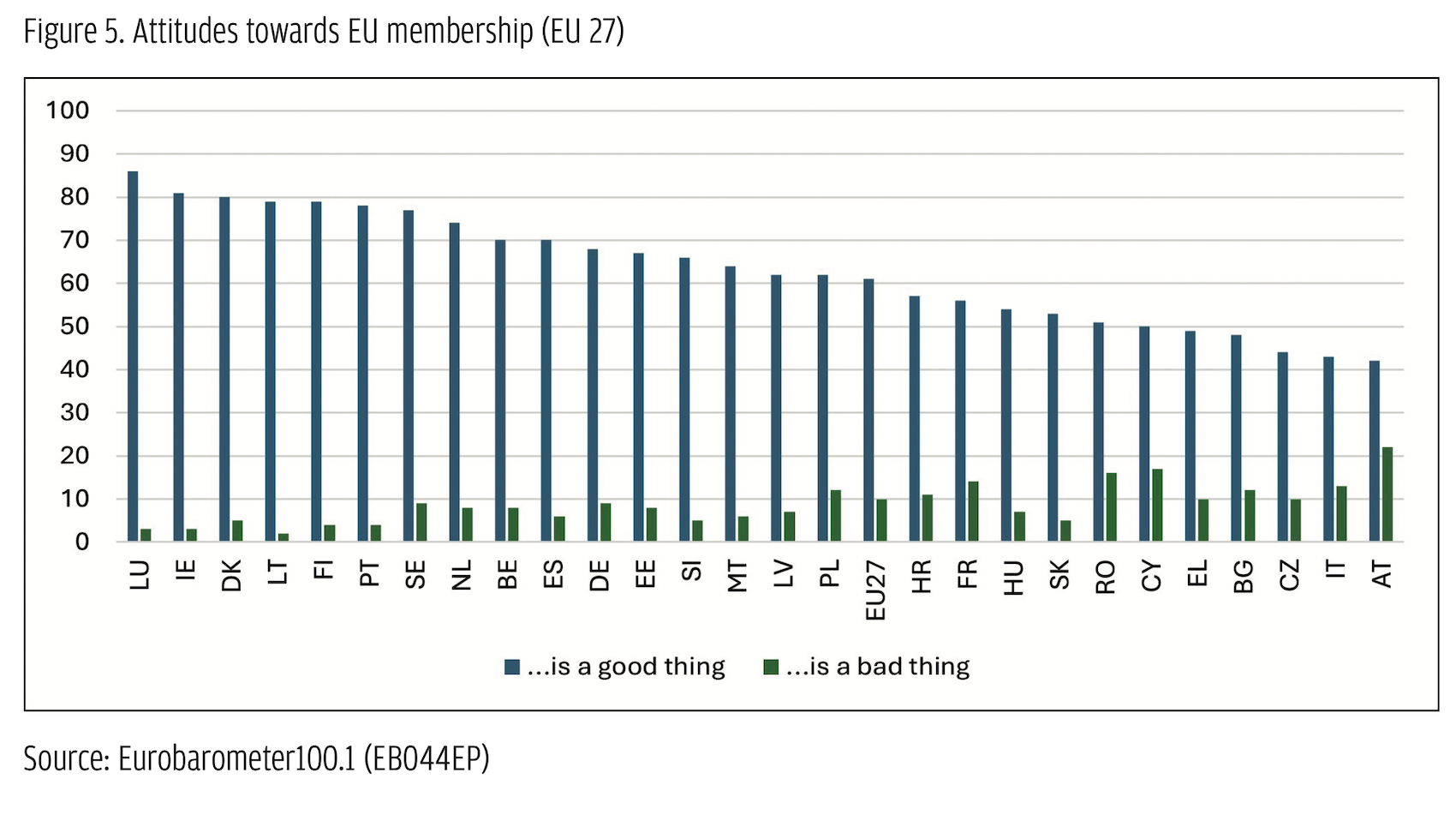

Looking at sociodemographic characteristics (Figure 3), the FPÖ somewhat underperformed amongst voters below the age of 30. Regarding education, it was most successful amongst voters who had completed vocational training and least successful amongst high-school and university graduates. Interestingly, and in line with preceding regional elections (Salzburger Nachrichten, 2024), the once significant gender gap has shrunk considerably compared to the elections in 2019. While back then, 26% of men but only 10% of women voted for the FPÖ, this time it was 27% of men compared to 24% of women. Amongst voters holding at least a college degree, the gap even vanished entirely, with 16% of men and 17% of women opting for the FPÖ (Laumer & Praprotnik, 2024). Amongst others, these changes may be a consequence of the position the party took during the COVID-19 pandemic (especially its critique to discriminate restrictions between vaccinated and non-vaccinated citizens) – which was also found among many (also highly-educated) women (Die Presse, 2021). Looking at voters’ issue preferences shows that, generally, there is quite a significant demand for EU-critical positions within the Austrian electorate. While in the 1994 constitutional referendum on the country’s EU accession, a two-thirds majority voted ‘yes’, approval rates started to drop soon thereafter, and Austrian citizens have ranked amongst the most critical ones across the EU ever since (Fallend, 2008). As Figure 5 shows, in the Eurobarometer from autumn 2023 (European Parliament, 2023), Austria not only recorded the highest share of citizens seeing EU membership as a ‘bad thing’ (22%) but also the lowest share of those seeing it as a ‘good thing’ (42%).

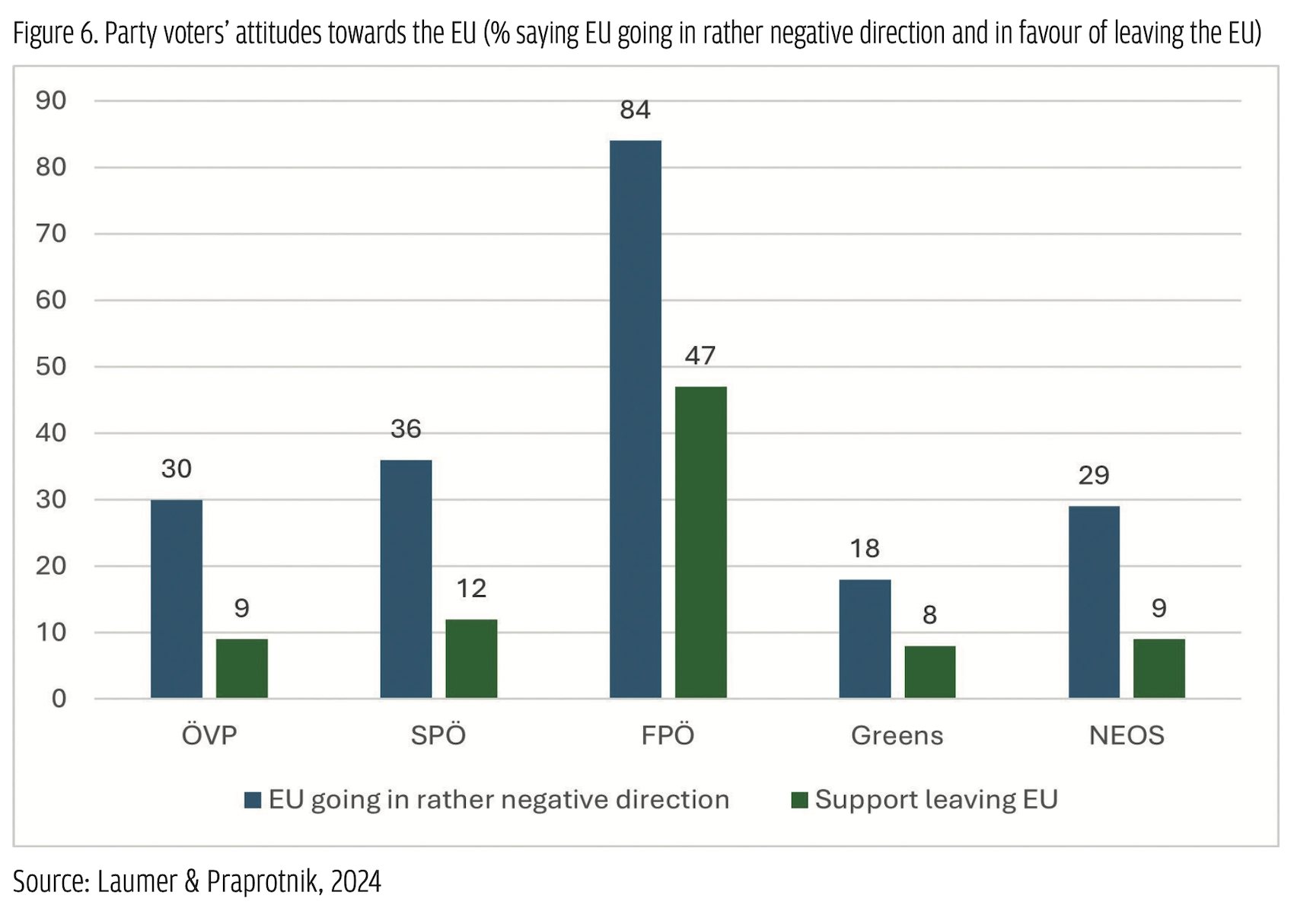

Looking at voters’ issue preferences shows that, generally, there is quite a significant demand for EU-critical positions within the Austrian electorate. While in the 1994 constitutional referendum on the country’s EU accession, a two-thirds majority voted ‘yes’, approval rates started to drop soon thereafter, and Austrian citizens have ranked amongst the most critical ones across the EU ever since (Fallend, 2008). As Figure 5 shows, in the Eurobarometer from autumn 2023 (European Parliament, 2023), Austria not only recorded the highest share of citizens seeing EU membership as a ‘bad thing’ (22%) but also the lowest share of those seeing it as a ‘good thing’ (42%).  The FPÖ was very successful in attracting these groups. According to exit polls, 84% of its voters see the EU taking a rather negative development and 63% would even support Austria leaving the EU (Figure 6).

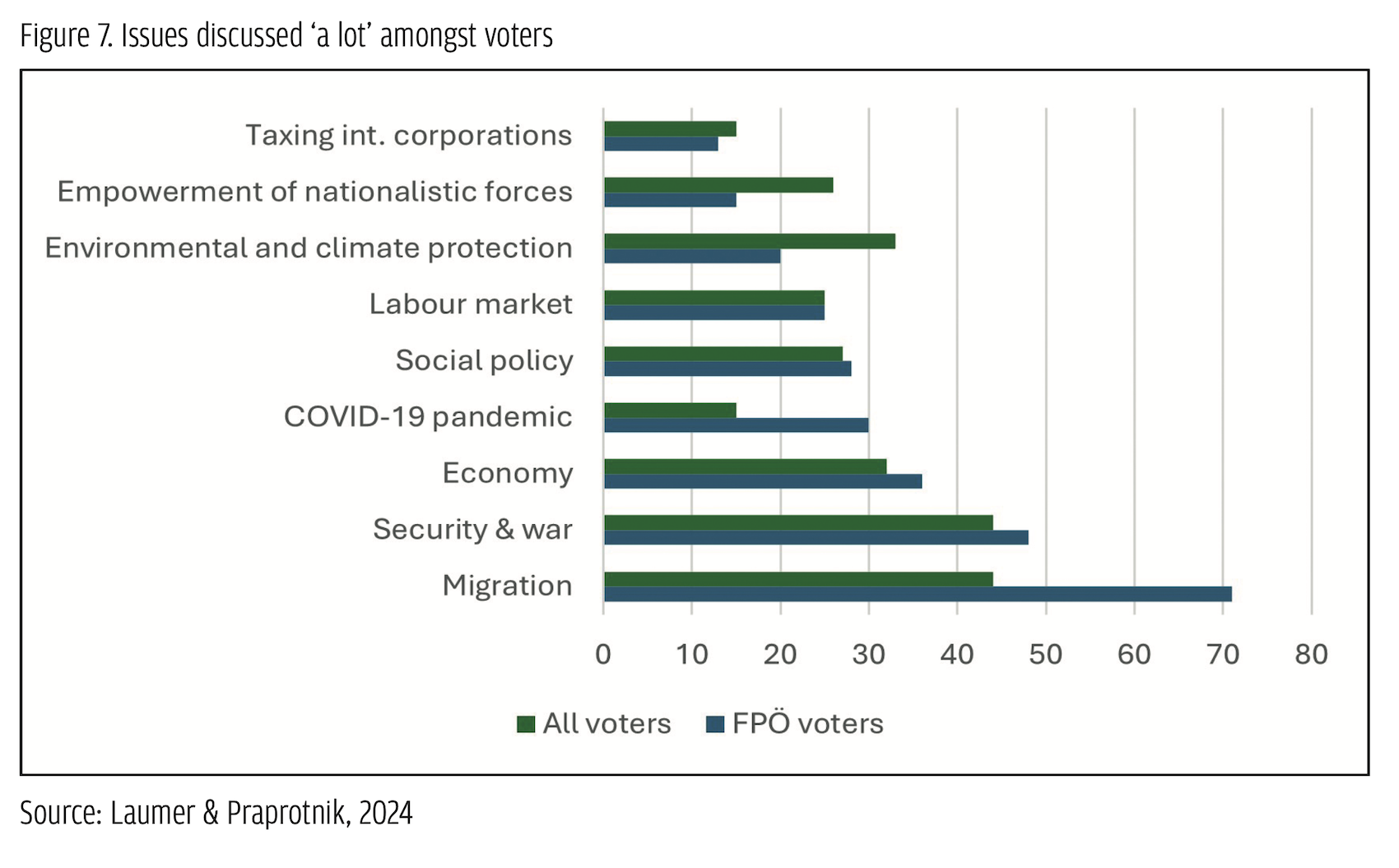

The FPÖ was very successful in attracting these groups. According to exit polls, 84% of its voters see the EU taking a rather negative development and 63% would even support Austria leaving the EU (Figure 6). Overall, however, only 4% stated that EU protest was their main reason to vote for the FPÖ, while 40% pointed to the party’s issue positions more generally. Looking at these issues, again, reveals a considerable overlap with the issues the party pushed in its campaign. Among the issues FPÖ voters discussed ‘a lot’ before the elections, ‘migration’ clearly ranks highest (71%), followed by ‘security and war’ (48%), the ‘economy’ (36%), and the ‘Covid pandemic’ (30%), with ‘environment and climate protection’ clearly lagging behind (20%).

Overall, however, only 4% stated that EU protest was their main reason to vote for the FPÖ, while 40% pointed to the party’s issue positions more generally. Looking at these issues, again, reveals a considerable overlap with the issues the party pushed in its campaign. Among the issues FPÖ voters discussed ‘a lot’ before the elections, ‘migration’ clearly ranks highest (71%), followed by ‘security and war’ (48%), the ‘economy’ (36%), and the ‘Covid pandemic’ (30%), with ‘environment and climate protection’ clearly lagging behind (20%). Public attention for the elections overall was relatively modest. About eight weeks before the elections, less than 50% of the Austrian electorate reported knowing the parties’ lead candidates, and even more stated that they could not assess their work (Die Presse, 2024). To the extent that the election was an issue, however, the FPÖ and its core issues featured quite prominently in the debates. In the three TV debates that featured all lead candidates, migration and the war between Russia and Ukraine were discussed for the longest time (followed by the climate crisis). Given the singularity of its positions, the FPÖ was criticized by all other parties quite harshly in all these debates. This criticism resulted in the FPÖ receiving by far the most attention and also allowed the party to (once again) present itself as the only ‘real’ alternative vis-à-vis a purported Einheitspartei (‘single political party’), composed of the ÖVP, the Social Democrats (SPÖ), the Greens and the Liberals. A similar phenomenon can be observed regarding general news coverage where, for example, the election poster discussed above met with extensive criticism by journalists both nationally and internationally, pushing attention to the FPÖ itself and its political demands even further (Hammerl, 2024).

Public attention for the elections overall was relatively modest. About eight weeks before the elections, less than 50% of the Austrian electorate reported knowing the parties’ lead candidates, and even more stated that they could not assess their work (Die Presse, 2024). To the extent that the election was an issue, however, the FPÖ and its core issues featured quite prominently in the debates. In the three TV debates that featured all lead candidates, migration and the war between Russia and Ukraine were discussed for the longest time (followed by the climate crisis). Given the singularity of its positions, the FPÖ was criticized by all other parties quite harshly in all these debates. This criticism resulted in the FPÖ receiving by far the most attention and also allowed the party to (once again) present itself as the only ‘real’ alternative vis-à-vis a purported Einheitspartei (‘single political party’), composed of the ÖVP, the Social Democrats (SPÖ), the Greens and the Liberals. A similar phenomenon can be observed regarding general news coverage where, for example, the election poster discussed above met with extensive criticism by journalists both nationally and internationally, pushing attention to the FPÖ itself and its political demands even further (Hammerl, 2024).